NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS FEBRUARY 1971 50 Cents

For the Record... REASONS FOR CHANGE

On October 8, 1970, the Game and Parks Commission approved a plan of reorganization calling for significant changes in various Commission programs and administrative structure. What are some of the reasons for these changes? How will they be made? What benefits can be expected?

First of all, improved efficiency of administration and operation is necessary. Increased responsibilities and new programs undertaken during the past 10 years have outgrown our administrative structure. Consolidation of some of our functions will result in more efficient use of personnel, equipment, and materials. In other instances, activities that have become outdated will be discontinued. Dollars will be saved in both cases.

Another aspect of efficiency has to do with improved communication. This must occur first within the agency itself, then with other agencies, and ultimately, the general public. We cannot hope to do an effective job of communicating with the public until we communicate well with ourselves. The reorganization plan is sprinkled throughout with devices designed for such improvement. Consolidation of the existing Game, Fish, and Research divisions into a Branch of Wildlife Services is an example of an attempt to improve "horizontal communication" within these biologically oriented units.

The establishment of an in-service training program in the Law Enforcement Division will be helpful in forging a communication link between biologists, conservation officers, and the public. The conservation officer is the agency's most constant contact with the people of the state, and is, therefore, in the best position to draw from and contribute to public information and interest at the field level.

Also built into the reorganization are some changes in program concepts. In line with current and future national trends, the agency recognizes the importance of non-consumptive use of all wildlife in addition to the traditional concern with consumptive use of game and fish. Efforts will be made to plan for and provide such uses as a com- plement to the current program.

It is planned to establish a metro-services representative in the Omaha-Lincoln area to better serve the great need existing there. He will provide for programs, make other public contacts, disseminate information in various ways, and interpret and relate metropolitan needs back to the Commission. Through this program we will hopefully develop new ways for the Commission to better serve this high-population area of the state.

While the first phase of reorganization is primarily one of consolidation, the second phase is one of administrative decentralization. This involves the placement of administrative personnel in the various district offices around the state who will be in charge of all Commission activities in the district, except for state parks. Placement of administrative authority in district offices will result in better supervision of agency personnel, faster action, and better fitting of our state programs to local needs.

The reorganization is also tied in with the new budget, and therefore is concerned with certain financial concepts that were altered concurrent with reorganization.

Finally, all aspects of reorganization are aimed at the ultimate goal of providing better service to the public at the least cost. The passage of time demands changes in all individuals as well as organizations if we are to effectively and efficiently meet obligations. We are trying.

Dick Spady Assistant Director, Game and Parks Commission FEBRUARY 1971 5WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM FEBRUARY 1971 5

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

INTERESTING — "I sincerely hope you will consider making small-town stories a regular feature because I believe they will be entertaining, interesting, and profitable for your readers.

"If it has not already been done, I believe a historical article in each issue would be appropriate. It could cover Indian tribal days, pioneers, settlers, and up to modern times, naming people, events, and families in the order of development." — P. E. Johnson, Hillsboro, Oregon.

LOOP THE LOUP —"We enjoy reading NEBRASKAland very much, but we do have one suggestion.

"The articles cover a lot of regions in Nebraska, except for the North Loup and Middle Loup areas. If anyone has ever traveled the area, they know some of the beauty of it. -Mrs. Jim Mingus, Dannebrog.

HELP —"I need your help to get word to Nebraska artists to find out what they are doing. We find that no single news media reaches all areas of the state as NEBRASKAland does.

"Artists should send in dates of their exhibitions, group and private showings, and workshops. Information should be sent to Mrs. J. E. Tracy, 420 Cloverly Avenue, Fremont." —Jan Tracy, Fremont.

ARTIST IN PRINT-"I have been interested in the series of Sand Hill country seasons by Marcia Greer. I hope you will encourage Mrs. Greer to contribute to NEBRASKAland more often. Her descriptions of life in her area are most vivid and enjoyable. She has a choice of words that paints pictures, and I feel as if I am in the midst of the Sand Hills." — Mrs. Helen Bradshaw, Denver, Colorado.

TERRIBLE —"There is something terribly wrong with the placement of the shotgun in the photo used with NEBRASKAland's, Harness for Field Glasses in November.

"The weapon is pointing toward a part of the lad. Even if there is a post between them, I would think the charge, whatever it might be, could go through the post, injuring him. Why take such a chance?" — Harold M. Hill, Prescott, Arizona.

WATCH IT —"I just received my copy of NEBRASKAland, November 1970.1 had to look twice at the picture on page 7 (Harness for Field Glasses).

"The young fellow showing how to use the harness for field glasses won't be using it for long if he continues pointing the barrel of that shotgun at his midsection.

"We realize the action is open. However, the reaction to the picture is not good. If the gun is placed in this position for a picture, it could very well be placed in the same position, with the action closed, during a hunt.

"We all enjoy NEBRASKAland, but do watch those pictures!" —Monty Weymouth, Chadron.

A closer look at the photo may point up some facts that were overlooked. First, the muzzle of the weapon is leaning back into a crack in the board fence and against the supporting post. Second, the shotgun is angled away from the hunter. This is, of course, standard practice for a good hunter. Sorry if the photo alarmed some of our readers, but safety precautions were taken. — Editor.

THE HARD WAY-"While in general practice with Dr. Slagle of Alliance in 1921, we received a call from a doctor in Hemingford. He told us that he had an Indian boy with diphtheria.

"Each year, several hundred Indians came from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, to dig potatoes.

"He requested all the diphtheria antitoxin available to inoculate the well children and treat the patients. I collected all the antitoxin in the area and asked the Box Butte County sheriff to help me.

"We spent all day rounding up uncooperative Indian children hidden under

wagons and in tents so that we could

inoculate them. Then, the sheriff ordered

the Indians back to the reservation so

that medical supervision could be effective. We had great difficulty getting them

FEBRUARY 1971

7

to move, as they were eager to make extra money harvesting potatoes. They

simply didn't realize the seriousness of

a diphtheria epidemic. The sheriff, with

the help of some co-operative Indians,

finally managed to head them toward

the reservation, however. This is really

practicing medicine the hard way."

— A. E. Bennett, M.D., Berkeley, California.

to move, as they were eager to make extra money harvesting potatoes. They

simply didn't realize the seriousness of

a diphtheria epidemic. The sheriff, with

the help of some co-operative Indians,

finally managed to head them toward

the reservation, however. This is really

practicing medicine the hard way."

— A. E. Bennett, M.D., Berkeley, California.

TALLYHOTHE PYTHON-"PythonPosse in the October issue brought to mind a similar incident.

"In 1928 or 1929, my husband and I were living on a farm a little ways northwest of Phillips. My husband was cultivating corn, when all at once the horses went crazy. There, in front of them, was a large snake. It was sort of spotted, and stretched out a little over three rows of corn.

"My husband finally made it to the end of the field, but then came to the house and told me. We went back to the field, and, though the snake was gone, we could follow its trail across the field to a culvert at a road leading down to the Platte River.

"Neither of us ever saw the snake again, though my husband always thought it probably got away from a circus." —Mrs. Mary Bartz, Lakeview, California.

INFO FOUND-"Reader Clinkenbeard can obtain information on carp smoking and smokers by writing the Wisconsin Conservation Department, Madison, Wisconsin. There is no charge for the material." —Ralph O'Dell, Lake Isabella, Calif.

LOVE THAT MAGAZINE - 1 wrote a poem about wildlife that I believe NEBRASKAland readers might enjoy as much as I like every issue." —Tom Green, Dundee, Florida.

WILDLIFE by Tom Green Dundee, Florida Many forms of wildlife Once roamed our beautiful planet; Buffalo, tiger, kangaroo, Condor, vulture, gannet. Man began to slaughter Creatures large and small, Some he killed in springtime, Others in the fall. The wings of passenger pigeons No longer fill the sky, Like other forms of wildlife, They were doomed by man to die. Buffalo by the millions Once roamed the grassy plain, Of that once vast number, Two very small herds remain. The greater auk is now extinct; Black-footed ferret, moa too, Still other forms of wildlife Live only in a zoo. The trumpeter swan still lives, Its numbers very slim, Whether it will survive or not, Depends on mankind's whim. The lowly mosquito too Is part of nature's plan, It also has to die, It is the will of man. Leopards are few in number now, Their skins made into coats, Other forms of wildlife Are hunted down in boats. 'Gators slaughtered for their hides; To man they cause no harm, Hides make a fancy handbag To adorn some woman's arm. Poachers take their daily toll Offish and other game, They are always first to cry That things are not the same. A lowly turtle on a road Moves with slow deliberate tread, A speeding auto passes by, And leaves the poor thing dead. Many forms of wildlife Along our highways lie, For stepping in the path of man, Needlessly they die. Once-pretty sandy beaches Are oily dirty globs, Tidal marshland must be drained For profit to some slobs. Because of the march of progress, Forms of wildlife have to go; To satisfy the greed of man; To earn him extra dough. With chemicals and pesticide Man pollutes earth and sky, To satisfy his lust and greed Still other creatures die. The waters of Lake Erie Are now completely dead, The mighty Chinook salmon Can't reach its spawning bed. One knows all that happens, That One up in the sky, He knows the creatures still alive, He knows the ones that die. A day of reckoning will arrive; That thought must make us quail, For as caretakers of our earth, My fellow man - we fail! 8 NEBRASKAland

DRIFTING INTO TROUBLE

by Edward Vrzal as told to NEBRASKAlandABOUT THE FURTHEST thing from our minds last April 10 i was snow. Yet we were driving into one of the worst blizzards ever to come down the pike.

As soon as we got off work Friday night, Bob Atkins, Les Shaffer, Norman Heckmann, Elmer Owens, and I piled into our converted, 34-passenger bus and headed west. We all live in Norfolk and had been planning this trip for some time. Spring was almost three weeks old, and for ardent anglers like us that meant fishing. This particular trip was to Merritt Reservoir near Valentine, about 200 miles away.

Despite the drive, we were up bright and early Saturday morning to give the trout a try. That night, we were back in the camping area west of the dam, more than ready to sack in after a long day.

I still don't know why I woke up about 4 a.m. the next morning, but it was then that I found out just how much trouble we were in. When we went to bed, there was little warning of what greeted me when I looked out the window. The entire area was white. There was an inch of snow on the ground - enough to worry me. In the hills around Merritt, even a little snow can make for rough going. That's why I shook my sleeping companions awake and announced our predicament. My warning was greeted by growls and grumbles. I was severely chastised and told to get back to bed. Consequently, it was after 6 a.m. when we next awoke and peeked outside. Trouble had multiplied in that two-hour sleep. There was more snow on the ground than we could possibly negotiate in the bus.

Somehow, we weren't too worried about the snow. We'd been caught away from the bus several times before. On those occasions, we simply spent the night behind a rock or under a tree. Things weren't nearly that bad now; we were in the bus and snug as could be. There were some good-natured comments bandied about, but the snow continued to fall. But then the wind rose-suddenly. As it grew in strength, it whipped the snow into the worst blizzard I had ever seen, drifting the white stuff and packing it around the bus, covering our boats and the dock.

The situation worsened when I, as cook for the crew, announced that our food supply was at austerity level. To get our minds off both the snow and lack of food, we broke out the cards. But man cannot live by poker alone, and as the snow abated late that Sunday afternoon we decided to try to break out of the bus.

It was cold, but the wind had died down somewhat, and Merritt's waters were still open to navigation. We decided our best mode of transportation to get out of there was by boat, and as we broke one of them loose, we hoped to reach a house nearby. In that open craft, we were at the mercy of the elements as we sped along the shoreline. A frosty breeze was making life pretty miserable by the time we arrived at the home of Kenny Hurlburt, area supervisor for the local irrigation district. And a welcome sight it was. Just the thought of different company was enough to raise our spirits as we knocked at the door. But we weren't prepared for what we found. Several other people had already made it to the house and, before long, a total of 24 hungry campers and fishermen had converged on the Hurlburts.

Many people also dumped their camping gear in the dining room. In our case, we managed one boat trip back to the bus to get our sleeping bags, but it was too miserable to continue going back and forth, so we bedded down at the Hurlburt home, too.

Late Monday afternoon, a ton of food after we arrived, a snowplow finally pushed its way through the drifts on the road and pulled into the Hurlburts' yard. Earlier, we had called a friend in Valentine and when the plow arrived he was right behind. Piling into the car, we headed for town, abandoning our bus and breathing a little easier.

We spent that night in Valentine and returned to Norfolk on Tuesday. Two weeks later, we were back to claim our bus and get in some more fishing. That was by no means the end of our ordeal, though. Since that weekend in April, all of us have been the targets of some friendly jokes. But we consider ourselves lucky, for if we had been farther into the hills, our situation could have been even worse. As it was, all of us came through the blizzard in good shape and we still make regular trips in our trusty old bus. None of us, though, will ever forget that weekend at Merritt Reservoir.

THE END When buying a Mobile Home Specify a Snyder Vista tub/shower ...It's a new vision in fiber glass...a new concept in tub/showers for mobile homes and apartment owners. Vista's offer more room for less money fitting in less space. The one-piece units have three strong molded side walls and tub. Beautiful to look at, yet built to last. Available in snow white or Vista colors at reasonable prices. PHONE (402) 434-9187

RAMADA INN

Washington Didn't Sleep Here! But John Dillon Did!

Each night our register includes many Johns, Dillons, Smiths, and Thompsons, and . . . Why Not Your Name? On your next business or pleasure trip to Lincoln plan now to stay at Lincoln's new Ramada Inn. Like they say —Here's "Luxury For Less." In fact, we say It's All Here This Year! See for yourself.Built in NEBRASKAland GO-LITE CAMPERS

GO-LITE HAVE ADDED CUSTOM BUILT UNITS 30' LONG BESIDES REGULAR MODELS 22'- 24'-25'-27' ALSO THE NEW INTERNATIONAL CHASSIS MORE SAFETY AND STRENGTH ALL INSIDE SHARP-CORNERED AREAS HAVE BEEN FOAMED AND VINYLED REINFORCED ROOF AND DOORWAYS-GRAB-BARS INSIDE OF UNIT FOR WALKING WHILE UNIT IS TRAVELING WE CUSTOM PLUSH MODELS IF DESIRED. FULL LINE OF TRAVEL TRAILERS FROM 13' AT $995.00 TO 23'-$3995.00. FULL LINE OF PICKUP CAMPERS. TODAY GO-LITE WILL COMPARE WITH ANY TOP LINE MOTOR HOME OR TRAILER. FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT GO-LITE CAMPERS, INC., OR VISIT THE FACTORY. WE SHOW YOU THE DIFFERENCE. GO-LITE CAMPERS, Inc. 23rd and SOMERS, Fremont, Nebr. 68025 AREA CODE 402-721-6555The great place to save in NEBRASKAland

UNION LOAN AND SAVINGS ASSOCATION 209 SO. 13 56TH and 0 LINCOLN 1716 SECOND AVE. SCOTTSBLUFFHOW TO: MAKE ROOM FOR PURPLE MARTINS

Homeowners love these sleek "skeeter-eats". Each eats over 2,000 mosquitoes a day by Norm HellmersALTHOUGH THE BALD eagle has been America's national k symbol for almost 200 years, certain bird enthusiasts, if they had their way, might like a change. The bird they are so enthusiastic about is the purple martin.

There are probably more martins nesting in the United States now than there were in 1776. Not the least of the causes of this phenomenon are the many dwellings that have been set up just for these birds. Martins were perhaps the first birds in America to use man-made nesting sites. Indians, well before the arrival of white men, hollowed out gourds and hung them from poles above their tepees. In colonial times, martin houses were set up each spring. Perhaps the oldest continuously used martin colony is in Greencastle, Pennsylvania, in use since 1840. More recently, the town of Griggsville, Illinois, has become famous as "The Purple Martin Capital of the Nation".

The qualities of purple martins that so readily endear them to the homeowner are many. The sleek, blue-black swallows are not only attractive in appearance, but are a joy to watch in flight. They are clean birds, easy to attract, and nest comfortably alongside civilization. But more importantly, martins are known for the amazing number of bugs they eat, especially mosquitoes. It has been conservatively estimated that one martin consumes more than 2,000 mosquitoes a day. So it is not difficult to understand why many people are anxious to have purple martins nest near their homes.

Martin houses are different than other birdhouses in several important ways. The gregarious "skeetereaters" like to live communally with other martins, so a house should have at least six compartments. There is no upper limit. Some have in excess of 200 units. The holes in a martin house are placed near the bottom of the compartment, rather than near the top, and need not be natural looking, as a fancy little castle in the sky is apparently just as attractive to the martins as a plain apartment building.

Many plans for martin houses, including those given here, follow a basic design originally published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Modifications can be made as long as certain basic features are main- tained. Each nesting compartment should be 6 X 6 X 6 inches, inside measurements. The 2^2-inch en- trance holes should be cut in the walls 1 inch above the floor. Also, some arrangements should be made for ventilation, since martin houses

12 NEBRASKAlandare always out in the open and can become quite hot in the summer while nesting is still going on. Most are made so that additional sections may be added later.

The house can be made from the following materials:

Exterior plywood: A 3/4 X 29 1/2 X 29 1/2 Attic floor B 3/4 X 26 1/2 X 26 1/2 Floors C,E 3/4 X 6 X 20 1/2 Walls D,F 3/4 X 6 X 19 " G 3/4 X 2 1/2 X 20 1/2 Base sides H 3/4 X 2 1/2 X 19(All the above materials may also be cut from Vfe-inch plywood but di- mensions of walls, oase sides, and partitions must be adjusted.)

2 I 1/2 X 16 X 29 1/2 Roof 2 J 1/2 X 6 X 29 1/2 Gables 8 K 1/2 X 6 X 19 PartitionsOak:

2 X 3/4 X 19 Center cross 4 X 3/4 X 8 1/2 "Other materials:

12 20 1/2-inch pieces of 3/4-inch cove molding 2 4-inch squares of screen 4 2-inch hooks and eyesAll wood pieces can be cut first, according to the dimensions given in the diagram. The partitions (K,L) can be notched halfway through so that they fit together in an "eggcrate" fashion. These partitions may be lengthened in order to dado them into the sides. Two Vi-inch holes should be drilled at the top edge in the center of each of these pieces as ventilation holes leading into the central air shaft. Next, the 2V2-inch entrance holes may be cut into the sides (C,D,E,F) and gables (J). The bottom of the entrance holes should be one inch above the floorline, while those in the gables can be centered. Bevel the roof pieces (I) and cut the center ventilation openings through the attic floor (A) and the middle-level floor piece (B). Once the 12

13 FEBRUARY 1971

pieces of cove molding, which keep the sections in alignment, are cut and mitered and the center cross pieces cut from oak or other durable wood, the materials are ready for assembly.

The birdhouse is made in three separate units: the roof and each of the nesting sections. The roof is made first. Nail the cove molding to the underside of the attic floor. Staple or tack a four-inch square of screen over the holes in the gables. Then the gables and roof pieces are nailed or screwed on top. Glue may be used on all joints.

The walls and partitions form the nesting sections. These sections are nailed or screwed to the floors, with the molding nailed to the underside.

Add the 2 1/2-inch base sides (G,H) to the bottom section. Within this frame rests the center cross built of a double-thickness of 3/4-inch oak boards, 2 1/2 inches wide. Depending on whether a 4 X 4 or a length of pipe is used for the pole, four heavy angle irons or a pipe flange should be bolted through the floor of the bottom section and the center cross.

The three units are held together with hooks and eyes. Building the birdhouse in sections makes winter storage easier and facilitates cleaning, a task which must be done each spring before the martins arrive. The house should be given two coats of white paint. Although martins have no color preference, white reflects sunlight and keeps the house cooler in summer.

The birdhouse should be placed on a pole 15 or 20 feet high, away from shade and buildings. The pole should be erected so that it can be easily raised and lowered. This can be done by mounting it between supports and attaching it with two bolts. When the lower bolt is removed, the upper acts as a hinge, allowing the birdhouse to be lowered to the ground.

Purple martins begin returning to Nebraska around April 1, and continue coming in the greatest numbers during the next two weeks. Though martins occur throughout the state, their range is generally restricted to the eastern third. Before building a purple martin house, it would probably be wise to make sure that martins are common in the area, as an unoccupied martin house will be taken over by less desirable house sparrows or starlings.

Once established in an area, the martins usually return year after year. The beautiful, soaring flight of the martins around their sturdy nesting house is a welcome sight over any homeowner's lawn or garden. THE END

NEBRASKAland 14

Rare Conquest

"Intrigue" of Nebraska's highest, lowest points captures studentsONE MAN'S CLAIM to fame lies in the fact that he drove a golf ball all the way across the United States. Another gained renown by standing on his head in front of the capitol buildings of all the states.

Famed mountaineer George Mallory insisted on climbing Mount Everest, even though he knew there was nothing on top but snow. When asked why he wanted to scale the mountain, he is said to have answered: "Because it is there."

Recently, NEBRASKAland Magazine was fortunate enough to enlist two young men with the same thirst for adventure and reckless abandon that must have marked Mallory. Throwing caution to the wind, they decided to tackle the highest point in Nebraska. Marty Mueller from Ogallala, and Eric Vant of Lincoln, both freshmen at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, knew Nebraska's highest point couldn't quite equal Mount Everest. But then, sometimes you have to make do with what's available.

The logical start seemed to be to locate the high point. A telephone call to the U.S. Geological Survey yielded a complicated, township-range description of the spot somewhere in southwestern Kimball County. Another call to Betty Allen, manager of the Kimball Chamber of Commerce, brought a more down-to-earth explanation.

"The high point is on Henry Constable's ranch, near the Nebraska-Colorado-Wyoming border," Betty reported. She also advised that we wouldn't need climbing ropes or other equipment. So, armed with this knowledge, we continued our planning.

On the morning of November 6, Marty, Eric, and I headed west. With spirits high and the lure of adventure egging us on, we must have been a dashing crew. But I was about to put an end to that.

"What happens if the high point isn't on the Constable ranch?" I figured if the thought was bothering me, I might as well pass it on to my companions.

Eric was panic-stricken. I had heard earlier, before my pre-trip investigation, that the spot was around Harrison. That was considerably north of our destination, not at all where we were headed.

"It says right here that the point is near Kimball," he choked, pointing to our references. Those papers may have made him feel better, but Marty still looked doubtful. After all, how would Mallory have felt if he had missed Mount Everest?

Now seasoned adventurers aren't supposed to need maps. So when we arrived in the Kimball area, we struck out to find the spot without any such aids. Half an hour later, we were still wandering around the countryside south of Bushnell. That's when Eric decided to break out the farm directory. He located the Constable ranch and reported that we had to go farther southwest.

"We can't go too much farther, or we won't be in Nebraska anymore," Marty cautioned. He was almost proved right when we finally arrived at the ranch. It was only three-quarters of a mile north of the Colorado state line and just two miles out of Wyoming. "You've come to the right spot," Henry Constable said when we knocked at his door and explained our mission. "Let me crank up my pickup and open some gates for you. You follow along in your car."

As we started up a field road, Henry pulled to a halt and walked back to our car. "I don't want you fellows to be disappointed when we get there." He seemed almost apologetic. "There's not a lot to see. I've been trying to get a plaque or marker put up, but I haven't had any luck. There's only a post to mark the spot now."

Assuring him that we just wanted to reach the spot, we continued up the bumpy road. Near the crest of the hill, Henry slowed his pickup and pointed to the right. A hundred yards away, 11 antelope surveyed us briefly before bounding over the hill. At the top of the rise, Henry turned the pickup around and stopped.

"You guys think you can make it from here?" he called with a grin, noting a yellow post 50 feet away.

"Looks pretty rough," Eric quipped, "but we can give it a try."

Marty's long strides brought him to the summit first, with Eric and me close behind. As we congratulated each other on completion of the "rough" climb Henry walked over.

"Well, this is it," he said. "For years they thought the highest point was up north. Then, a few years back, they started drilling for oil in this area. A fellow took an elevation reading at his rig and found he was higher than the accepted high point in the state. More than that, they were drilling in a draw. That's when they started looking around and found this

spot. We are 5,424 feet above sea level." Besides being our tour guide, Henry had a ranch

to run, though, so he headed for home. We

watched him go, then Marty turned to Eric.

spot. We are 5,424 feet above sea level." Besides being our tour guide, Henry had a ranch

to run, though, so he headed for home. We

watched him go, then Marty turned to Eric.

"We're higher than Denver."

"That's true," Eric answered, "but that little rise over there looks even higher."

"Let's check it." Marty, an engineering major, pulled the transit from the car and set it up. As Eric headed "up the rise" it was obvious that he was walking downhill. The transit confirmed it. The true high point was 18 inches higher than the "rise".

"I guess this is it," Eric observed when he returned, "but that's some optical illusion."

Flag raising was our next task. We had agreed before leaving Lincoln that raising a Nebraska state flag would be a fitting tribute to our "climb". It turned out to be about the most difficult part of the journey. A stiff, gusty wind unfurled the blue banner, making its raising a real chore. But Marty and Eric struggled valiantly, and finally hoisted the mast into position. We planted it firmly in the ground, then stood back to look. Our conquest was rare indeed, but we managed to experience a bit of that same feeling Mallory must have had when he reached Mount Everest's summit. Then we packed our gear and left.

Back at the ranch, we stopped to thank Henry for his help. He met us at the door and asked us to sign his "high-point register".

'We're off the beaten path, so not too many people get out here," he explained. 'I just started keeping a log this spring. Wish I'd thought of it sooner. It would be interesting to look back and see who has been here over the years."

Henry saw us off with a wave and a friendly "You fellows come back and see us." We started home. For some time, we rode in silence.

"I guess quite a few people have been to Nebraska's highest point," Eric finally observed.

"Well, it's not too tough," Marty grinned.

"But I wonder if anybody has ever gone to the lowest spot," Eric mused.

"That's a great idea," Marty beamed. "The highest spot and the lowest spot. Let's do it."

"I'm game," I put in. 'When do you want to go?"

"How about tomorrow?" Eric asked. We all agreed, and that settled it. Spending the next half-hour speculating about where the lowest spot might be, we finally agreed it was likely to be somewhere in southeastern Nebraska. I was assigned to find its exact location. Another call to the U.S. Geological Survey confirmed our speculation. I learned that the lowest spot is in the extreme southeastern corner where the Missouri River flows from Nebraska into Kansas. An elevation check revealed that the low point fluctuates between 835 and 840 feet, depending on the river's level.

By noon the next day, we were on our way to Rulo, the town nearest our destination. As was the case with the high point, the low point was on private land. So, when we arrived in Rulo, our first task was to find the landowner, and an hour later, we discovered that he was a doctor in Kansas City, Missouri.

"That's a bit too far to go this afternoon," Marty grinned.

"What do you say we drive past the place again before we head back?" Eric queried.

A cornfield stretched from the road to the river's brushy edge. As we approached, we saw a corn picker in the far corner of the field.

"I'll bet that's the guy who rents the land," I said. "I'll hike in and ask him if we can cross to the river."

I caught the picker just as it rounded the end of the rows.

"You want to do what?" was the answer to my question.

"We're trying to get to the lowest spot in the state. From what we've been able to find out, it's right where the Missouri River crosses into Kansas."

"That would be right over there, where the fencerow runs to the river," the farmer said. "Go ahead." I couldn't help but notice him shaking his head as I walked away.

"Let's go," I yelled as I trotted up to the car. A field road took us to within a hundred yards of the river. We had visualized the low spot as part of a broad, sandy beach. But what met us as we hiked toward the river was a maze of weeds and willows.

Just as we plunged into the heavy brush, I remembered two machetes in the car. In a matter of minutes, Eric and Marty were hacking a path through the undergrowth like a couple of jungle fighters. I brought up the rear. About halfway through (Continued on page 64)

DESTINED TO DIE

Even as thundering hooves of the Pony Express echoed across stae, click of telegraph foretold doomFEW PERIODS IN western history excite the imagination as much as the short-lived reign of the Pony Express. Its legendary riders shuttled mail across the unsettled frontier at breakneck speed, while the railroad inched westward, and the first telegraph line was being strung across the country.

Although it lasted only 18 months and proved a financial failure in itself, the Pony Express survived through a series of stagecoach-line mergers and takeovers as one of the most colorful episodes in taming the West. During the Indian Wars, these daring young riders dazzled even the doughty by carrying mail from the Missouri River across Nebraska Territory to the West Coast through tough terrain, no matter how hostile the Indians or how rough the weather.

But the Pony Express was destined to die even before it began. Eventually it would become part of the Wells Fargo stageline, thus adding to this western giant which emerged supreme in the stagecoach business some 20 years after the discovery of gold in California.

While there had been other attempts to organize similar operations during the 1850's, the Pony Express, in operation from April 1860 to October 1861, is what historians have labelled the one and only because of its success and the spectacular way in which it was run.

It was a significant step in mail service across the West. But more than that, it served two significant purposes. The superiority of the central overland route, as opposed to a southern route to San Pedro, California, and then north by ship along the Pacific Coast to San Francisco, was established. And, California's allegiance to the Union at the beginning of the American Civil War was solidified because of the speedy delivery brought about by the Pony Express. Stagecoaches took approximately 25 days to travel from the Missouri River to California, but a Pony Express delivery was scheduled for only 10 days in summer and 12 in winter. Historians might argue the point of just how significant a part this colorful company played in keeping California in the Union during the Civil War, since coast-to-coast telegraph communication began late in 1861. But the fact remains that delivery time was cut in half.

The Pony Express was the result of a bold, adventure some scheme, organized in 1860 by three westerners—William Russell, Alexander Majors, and William Waddell.

During the 1850*8, the federal government awarded mail-delivery contracts to various stagecoach companies, depending on which could cross the West with the least number of mishaps. Service was erratic. Also, there was stiff competition between advocates of the central and southern routes.

But in 1860, Russell, Majors, and Waddell of Saint Joseph, Missouri, gained control of carrying the mail from the Missouri River to Salt Lake City. Earlier, they had operated short runs between Missouri towns and army outposts on Nebraska Territory's frontier, reaching out as far as Fort Kearny. At the end of the decade they wanted, once and for all, to establish the fact that the central route was the fastest way to California. Their problem was how to do it. That's when they came up with the Pony Express.

It took some doing, but they persuaded the federal government that if they were to get the mail contract along the entire route, they would deliver in 10 days or less. If they fulfilled (Continued on page 54)

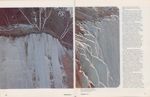

ICE WALLS OF THE NIOBRARA

Awesome in their grandeur, cliffs are designed and doomed by natures whimsical soulTHE EBB AND FLOW of the seasons reveal the intricacies of nature, and wherever the difference between winter and summer is more pronounced, scenic contrast broadens. The Niobrara River wends its way through verdant valleys in summer, but in winter it stops, frozen in the grip of the seasons.

Here, one of nature's most spectacular phenomena unfolds as icy walls appear on cliff faces near Valentine. Designed by Mother Nature to guide the river along its course during summertime flow, sheer cliffs along the river inside the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge don an iridescent glow. Moisture from seepage springs at the brinks of the cliffs, coats the walls, and freezing temperatures hold this moisture in suspension, draping it over the escarpments with glacier-like pace.

The ice walls reach the height of beauty during winter's coldest days in late January or early February. Beauty is most brilliant late in the afternoons when sunlight skims across the fluted surfaces. Pale blue and green areas of ice

appear where the water carries minerals dissolved from the parent earth.

The Niobrara ice walls are a sight well worth the effort it takes to reach them. Access is gained several ways. Visitors may drive 3 miles east from Valentine on Nebraska Highway 12, stopping at the bridge which leads to refuge headquarters. There is a lookout point above Fort Falls near refuge headquarters. The lesser of the walls can be seen from there.

Perhaps the most adventuresome and aesthetically pleasing way to see the icy spectacle in its entirety is to hike the river, starting from the bridge. Snowshoes, although not mandatory, are recommended if the snow is deep. Ice creepers on shoes are also an asset while walking on slick surfaces.

The lesser of the walls is first in line, rising up from the north bank. Farther on, the small tributary from Fort Falls joins the Niobrara. A short detour up the tributary leads to Fort Falls, blanketed in ice with the water still rushing behind the sheath. Returning to the river, just downstream from the junction is the second of the ice walls. Still farther east is the buffalo bridge, used to drive the animals north and south across the river each spring and fall.

The river bends just beyond the bridge. The biggest and most spectacular ice wall is in the river's curve to the south. Along a 150-yard span there, the ice builds up to heights of 40 or 50 feet. The moisture is barely enough to keep the wall damp in summer, but in winter it freezes as it emerges, building to a thickness of three or four feet, depending on the weather.

Another way to see this natural beauty spot is to drive a snowmobile on the river's ice, but this is hazardous because the river has been known to open up during extended warm spells. When this happens, a canoe can be used, but this again is extremely dangerous because floating ice can damage the craft.

The walls are seemingly static, but there is constant, intricate movement from day to day as the icicles lengthen and the castles build up from below.

When spring arrives, the walls facing south disappear first. Those facing north stay longer, sometimes melting gradually, sometimes dropping off in chunks to be carried downstream by the current. And so an ebb of nature yields to the flow of spring as another of Nebraska's wonders passes. THE END

RECORD FOR NOW

Winsome woman waits it out and finds patience pays off when she pulls whopping scrapper from Big Mac's depths by Lowell JohnsonALMOST AN HOUR before dawn, the 17-foot inboard pushed its way out of Lemoyne Bay at Lake McConaughy and turned east toward the dam. Four anglers aboard the craft hauled in a few white bass as they trolled toward their destination, but weren't dissuaded from their original goal —Arthur Bay.

A strong north wind buffeted them, so they decided to pull the boat far up into the cove and drift out with the wind, rather than troll or anchor. They cast and retrieved or jigged the lures as they drifted.

It was still before sunup when the first customer grabbed a line. A treble-hooked, white slab on the business end was doing its job. The slab was a three-inch, heavy metal spoon rounded at the ends, a favorite lure for white bass and walleye at McConaughy for several years now.

After an exciting few minutes, the fish was hoisted aboard. Rather than a husky white bass, they found a striped bass on the lure, one that weighed slightly more than five pounds.

The two couples in the boat, Barney and Dixie Akers, and Gerald and Marceda Schmidt, knew what the state's striper record was, for an 11-year-old boy, an acquaintance from Syracuse, Kansas, presently held it. The record was over six pounds, and their little portable scale showed this fish to be less than that.

A day earlier, the second of their three-day trip to McConaughy from their homes near Kendall, Kansas, Gerald had hooked a fish about a quarter of a mile from where they were now fishing. After just a few minutes of fighting, the fish broke the line and made its escape. That episode was partial reason for choosing Arthur Bay today.

Within minutes, another striper took a spoon and was brought aboard —one that later scaled out just an ounce short of six pounds. Then Mrs. Schmidt latched onto one that wasn't brought in. The line gave way before the battle could really get started. But, every hit now added optimism to the morning venture. A third bragging- sized fish was soon added to the stringer, and it looked like a promising day for the quartet of anglers.

Still several minutes before the sun cleared the horizon, Dixie Akers felt the little dance that signaled (Continued on page 64)

FEBRUARY 1971 29

ACTION IN THE RING

Country cattle auctions are outing for city slickers, but for ranchers they decide the fluctuating prices of prime beef

WHEN IT IS ALL said and done, the whole thing comes down to one word — profit. Yet, the cattle auction, a mainstay of Nebraska's agrarian economy, somehow comes off like a country fair, a gigantic shopping spree, and a neighborhood reunion all rolled into one. In fact, an auction probably packs more enjoyment, inch for inch, than any other spectacle of its kind in the state.

There is a common misconception about the cattle auction, be it in Nebraska or any of a dozen other states which depend heavily on the cowman and his product to bolster their economies. Urbanites, whose closest connection with beef is on a platter, seldom see the possibilities of the cattle auction as a place to go or a thing to do. Despite their down-on-cattle attitudes, this carryover from the days when railhead towns like Nebraska City, Ogallala, and Sidney spelled income for Texas cattle barons, still means an outing that is hard to beat.

Almost every Nebraska community, be it large or small, boasts a sale barn. Names for the structures vary, but the auction is the same. One day a week, ranchers gather to buy and sell their hooved gold. Sale day starts early, with many consignments shipped in by truck or rail the previous day. Some cattlemen prefer to pen their animals for a while prior to the sale, since the critters often lose weight in transit. Whatever the case, however, holding pens at the pavilion are seldom empty for more than a few days at a time.

Visitors would do well to arrive as early as the cattlemen if they want to get in on a piece of the action. A healthy share of the bickering, so common to sales, is never seen in the ring. And, at least a few of the consignments never hear the staccato chant of the auctioneer. They are spotted, evaluated, and snapped up by cattlemen seeking top stock, before they can be herded into the ring. The (Continued on page 62)

30 NEBRASKAland

Bushytails in Ambush

Corn-fattened squirrels reward hidden nimrods. Waiting is name of game by Jon FarrarHUNKERED DOWN in browning stands of seedless brome, a pair of camouflaged nimrods carefully eyed the no-man's-land between the river's brushy edge and the cornfield. Glistening frost, capping broken cornstalks, was preserved by long shadows of cottonwoods fingering out over the field. The night-cooled earth worked chills through layers of wool to pierce tender skin. The climbing sun etched a miniature horizon on a distant stand of ancient cottonwoods that fringed the peaceful Loup River bottomland near Monroe. Silhouettes of aging bow stands from years gone by seemed to mock the two squirrel hunters below.

A familiar shadow, originating from a nearby tree, pranced smoothly over the jagged field. Eager for action, Gary Ziegler pivoted to pinpoint the bushytail. Cautiously circling the tree, Gary almost missed seeing the squirrel frozen near a bowl-like depression 20 feet above. But he caught a glimpse of the prey and a .22-caliber slug whistled through the morning stillness,

32 NEBRASKAland

smacking the bark below the rusty ball of fur. The squirrel's split-second pause gave Gary time to flick the selector button on his over-and-under. The solid "whump" of his .410 anchored two pounds of tasty meat securely in the wood pocket. Jerry Engberg, the second hunter, joined his partner at the tree.

Jerry, a self-employed carpenter and cabinet maker in Monroe, had teamed up with Gary, partner in a Monroe-based gas-propane retail business, for a day's pursuit of squirrels. Now, the two joined forces to retrieve the hunt's first prize from where it was lodged. Attempts to find a dead branch long enough to reach the bushytail failed. The piggyback method was out, since Gary's leg was still on the mend from a recent break. Finally, the team clicked as Jerry, an ardent cooner and veteran of many tree climbs, shinnied up a young mulberry close beside. With stick in hand, he freed the prize.

Gary's disappointment at the sight of so few of their intended quarry during the first 45 minutes of the hunt ebbed as Jerry recounted an earlier sighting. Several bushytails had been feeding in the corn just off a wooded point across the field.

Moving to a more promising site was in keeping with their original objective —to ambush a bushytail between timber and cornfield. Conceived and considered during many a cold morning of fruitless bow hunting, the idea to bag a respectable platter of under-harvested fox squirrels had finally come to be. The camouflaged suits, the memory of the three white-tailed does in the corn early that morning, and, most of all, the frigid waiting were reminiscent of past bow hunts.

Jerry settled into the willow peninsula so that he had a good view of several gnarled box elders near the core. After 10 minutes of idle wandering, Gary nestled under a fallen tree overlooking the cornfield. Near the remains of a bushytail's meal of corn on the cob, Gary awaited the gourmet's possible return. Partially eaten kernels reminded Gary that some people think fox

The whistling twang of Jerry's .22 shook Gary from his contemplation and had him on his feet and moving. When he arrived, Jerry was retrieving his trophy, and the story unraveled. The flick of a tail was the russet rodent's first mistake. An extended version of "hide and seek" ensued until Jerry's patience wore thin. A snap shot at a slightly revealed head ended the game. Not to be outdone, Gary renewed his search for the tiny targets.

His halfhearted shake of a four-inch sapling jarred two surprised family members from their high, leafy nest. A snap shot at one of the treetop acrobats from Gary's .410 was a washout. Jerry, meanwhile, drew bead on the second squirrel and, during one of its brief stops, brought down his second take of the morning. The two "camoed" hunters dismissed the other rascal with the feeble rationalization of "leaving seed for another year".

Theories tested and revised, the duo decided success might be waiting along the wooded border of an unpicked cornfield. A move into the rolling farmland provided another invitation to a bushytail bonanza.

Two "yellow bellies", caught feeding on the ground, skittered up an aging box elder. Dancing from tree to tree, the larger of the two found retreat in a hollowed branch. The other used the age-old ruse of slipping around to the far side of the tree and lying "doggo". Gary's calculated arrival on the same side forced the bushytail to shuffle back around the tree into Jerry's waiting gun sights. A resounding "thump" brought the pair's fourth prize to the leaf-littered ground. Gunfire, however, is the squirrel's best burglar alarm. So, Jerry and Gary decided to sit and wait for awhile.

Nestling down under gently leaning trees for the second time in the day, the now-enthused advocates of "squirreling" took up (Continued on page 55)

Bins of Plenty

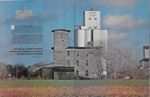

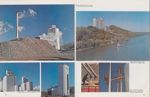

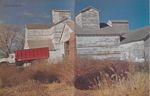

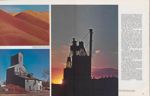

Cornucopias of hopes and dreams, mammoth grain elevators are symbols of the state's agricultural heritageSTOIC AND SILENT through the decades, Nebraska's "Cathedrals of the Plains", the mighty grain elevators, stand watch over the destiny of the land. Deep in their bowels, they harbor the dreams and aspirations of an agrarian society, yet, many of those for whom they stand frequently pass by without notice.

Where once there was only rolling, unbroken prairie, these glistening monsters now jut skyward. Often the focal point of community life, they are just as often the forgotten symbols of a way of life as they tower over hamlet, village, or town. Still, despite their passive exteriors, they are alive with activity that escapes all but the innermost of the farming fraternity. It is an activity that rises from obscurity to prominence with

Photographs by Bob Grier

the cycle of the seasons. Summer brings a bustle to shatter the sleepy days of winter and spring. Grain-hauling days slip into weeks as the elevator envelops bushel upon bushel, ton upon ton of golden wheat. Products of a co-operative venture, these giants house not only networks of augers and pulleys, but also capture the essence of modern-day agriculture. In doing so, they become the focal points of myriad activities.

Farmers, eager to begin their harvests, arrive at the elevator office with samples of grain to be tested for moisture content. If the grain is too wet, it may mold in the bin or explode into a ravaging inferno through spontaneous combustion. Yet, to let the wheat dry in the field is to court the disaster of nature —hail. That is a threat few farmers can afford. So, the elevator plays vital roles in the drama from harvest to storage. And the word that the grain is ready for reaping sends farmers scurrying to their fields.

In what seems like a matter of hours, the convoy that once held cars with grain samples, boasts trucks heaped high with golden grain. For some, the wait seems endless as each load is weighed and evaluated, then augered into the yawning emptiness of the elevator. And, as word spreads that it is time to harvest, streams of vehicles seemingly stretch to the horizon.

But the elevator in today's world of peak productivity is by no means the last word in efficiency. Storage space is not limitless, and the cooperation of elevator and railroad is a marriage of growing importance. As yields increase, grain carriers are often unavailable when they are needed. In the crisis, mountains of grain grow beside the elevator. And, by the end of harvest, NEBRASKAland finds a new aspect to its farming scene. Tons of grain sprawl on the ground as the monster at its side returns to the apparent hibernation of the changing seasons.

Silent, but not sleeping, the massive elevator remains a beehive of

activity far into its depths. Grain is sorted and cleaned, evaluated and stored. Bookkeeping runs into mammoth proportions as personnel strive for perfection in limitless paperwork. And, as the means become available, shipments are made to the processing centers of the east. Still, from afar, the elevator sleeps in silence, its job done for another year. A beast of burden which has completed its task, the elevator lapses into the serenity of the ages.

With the end of the hustle and bustle and the calm of a rural fall and winter, however, comes a picture-postcard kind of beauty. In tune with the symphony of the seasons, the elevator stands out in artistic relief from the fiery colors of autumn. And, as falling leaves transform into blowing snow, the white edifice lies spectre-like against the mantled landscape. Almost fading into the surroundings, the elevator once again becomes a monument to those who till the soil. And, like so many monuments, it is almost forgotten in its presence.

To forget is often to ignore, but elevators are seldom ignored. Because of their sheer bulk, if nothing else, they edge into the fantasies of childhood and into the everyday life of adults. To a tot, the towering brilliance of the elevator conjures mighty mountains or any of a thousand infant dreams.

Or to the adult, they rise as beacons of safety in the inky blackness of a rural night. The way to shelter is guided by these landmarks as heralds of home and hearth, and many is the time a stranger has taken his bearings from an elevator.

These, then, are the monuments Nebraska has made to its heritage of the soil. In their unique way, they are as common as the dawn that follows the night, and still as singular as the face of the changing land they dominate. In them the imaginations of tots and the aspirations of adults become realities. THE END

45

HOOK, LINE, AND ELECTRODE

Proof of fish-migration theories comes to light, an added benefit as trap on North Platte River swings into peak efficiency 46 NEBRASLAlandFISHERIES BIOLOGISTS always suspected it, but a fish trap finally proved it. Rainbow trout definitely migrate from Lake McConaughy up the North Platte River to spawn, and then return to the reservoir.

Proof of this theory has come to light during the 1968, 1969, and 1970 seasons since an electrical fish trap, called a weir, has been in operation at the western end of Lake Mac just above the river's mouth. Although not major among conclusions derived from the fish trap, it is probably the one most likely to attract angler interest. Valuable information about the rainbow trout has been gleaned from studies connected with the weir to provide sport fishermen with even more clues on how to catch this elusive game fish.

Impounded at the eastern end by Kingsley Dam, second largest earth-fill construction of its kind in the world, Lake Mac is fed by the North Platte River from where it slashes through west-central Nebraska. With a source so mighty, it was only natural that Big Mac became a recreational area. But now, the lake and its tributary are also becoming important links with Nebraska's future fish production, especially since com- pletion of the weir,in 1967.

The whole thing started back in 1964 when Congress passed the Commercial Fisheries Research and Development Act. The law authorized the Federal Government to co-operate with state agencies on specific projects relating to commercial fishery resources. That year, Nebraska submitted a project proposal through the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries in Washington. In 1967, the state's Commercial Fishery Investigations project swung into operation. A continuing project, its objectives are to assess current stocks of sport and commercial fish in Nebraska reservoirs, and to establish the possibilities of an annual commercial removal program.

Fish-population counts by various methods had begun in 1955. These projects, which ran until 1966, indi- cated that approximately 60 percent of the lake's population consisted of rough fish —carp, quillback, river carpsucker, gizzard shad, and white, redhorse, and longnose suckers, the slough of the anglers, seldom kept when caught.

According to earlier research, large numbers of rough fish gather at the upper end of McConaughy during spring and early summer before moving west into the North Platte River to spawn. With information like that, it seemed that the river's mouth was the most suitable place to establish the fish trap. This installation soon became the key facility in the project.

Essentially, the weir consists of three electrical suspensions across the river. These form a barrier to fish migrating upriver, thus creating a trapping and holding area. Located 2.8 miles east of U.S. Highway 26 near Lewellen, the weir was established at the site of an abandoned irrigation diversion, which became obsolete with the completion of Kingsley Dam in 1941 and the subsequent buildup of water in the lake. Development began in January 1967 with initial construction in May and completion in September. When it was finished, three specially made electrical units supplied current for the suspensions, and the study began.

Fish research is no easy task, and much thought and planning went into construction of the project. Each of the three units receives power from a commer- cial utility source, then converts this power into pulsed, direct current which in turn energizes the suspensions. Direct current was used to keep fish mortality at a minimum, since it (Continued on page 63)

46 NEBRASKAland

CHRONICLE OF CHANGE

Photographers of 100 years ago and today compare scenes of Pine Ridge finery at Fort Robinson settingNOTHING, THEY SAY, is so certain as change. Environmental forces dictate the alterations of lower forms of life. Landscapes are worn and weathered by man's meager efforts and nature's whimsical plots. Change is accepted as the norm. Yet, in distant corners of the mind, memories linger of things as they used to be. Tree stands of years gone by remain as veiled recollections long after they disappear. Age-old hills, undermined by a link in the highway chain, shimmer in misty memory. Man, though, has devised a more lasting means of preservation - the precise, all-seeing camera.

Living in a world where yesterday's landscape is today's memory, photographers keep a lasting chronicle of change. Photographs of today become objects of contrast with their predecessors. Technical excellence has no place here. Comparison is the key that is used to unlock the configuration of the past. The accompanying photographs should be evaluated in this way.

Products of William H. Jackson, the dean of American photographers, and Lou Ell, chief of NEBRASKAland's photographic section, these scenes offer a study in the changing face of Nebraska. They are the embodiments of change and of nature's passive resistance to that transformation throughout the last century.

A nation in turmoil greeted Civil War veterans. Few returned to life as they had known it. The antebellum South, crushed, lay smoldering in defeat. An

industrial North was verging on advanced mechanization, altering its peoples' lifestyles as it went. Footloose, many ex-soldiers from both sides headed West to build new lives in a virgin land. Among them was William H. Jackson, an Omahan with the wanderlust of a Gypsy. Jackson's roving led him to California, but it was a short stay. By 1868, at age 25, he was back in Omaha to set up a photographic studio.

Years of war and his stint on the western frontier, however, made city life tough for the young photographer. He wanted out, and he had the perfect solution. Turning much of the studio's operation over to his brother, Jackson built a traveling darkroom on a wagon frame and headed for the hills. He contented himself, at first, with rambling the area around Omaha, shooting portraits of local Indians. But that also proved to be too tame for the young artist's free spirit.

In 1869, about a year after establishing his studio, William H. Jackson was ready to move on to bigger and better things. Scheduling a trip west on the newly completed Union Pacific Railroad, he loaded his equipment, turned the remainder of the business over to his brother, and lit out. That trip was the turning point in his career.

Photographing landmarks and people along the route, Jackson soon attracted the attention of Dr. F. V. Hayden. A surveyor engaged in several geological surveys of the West, Hayden took an immediate fancy to the young photographer and his work. He was so impressed, in fact, that he arranged for Jackson to accompany the crews as their official photographer. With his love for life in the open, Jackson probably couldn't have been happier. Still, a photographic existence in a rail car was vastly different than in a studio. And, his work with the surveyors was to be, at best, unique.

Long before the advent of roll film and instant development, Jackson's equipment posed some interesting problems. His gear would have made most of today's paraphernalia look like studies in miniaturization. Large cameras and wet plates — the negatives of the day — had to be carted from place to place, no easy task in the frontier West. Since Jackson's subjects were often in some of the wildest country west of the Missouri River, a wagon darkroom was out. Railroaders of the period had their hands full just maintaining track they already had down and weren't interested in extending lines into the back country. So, taking such things into account, Jackson hired an assistant, loaded his belongings and equipment onto a mule named Hypo, and set off to make photographic history. Little did he know that, through his wanderings, he would become one of the best-known early western photographers.

With Nebraska his home, it seemed only fitting that Jackson devote at least part of his talents to the state's landmarks. With a series of photographs of attractions throughout the state, he did just that. The cameraman dealt primarily with the Pine Ridge, though some selections portray eastern Nebraska landscapes and notable subjects in Lincoln and Omaha. During years afield, he compiled a large collection of photos, a large portion of which now rests in the Colorado State Historical Society in Denver. Some examples of his work are presented here. Along with them are re-creations of the photographs, taken from the same locations Jackson used in his artistry.

This, then, is the meeting of two worlds. One is the world of William H. Jackson, frontier photographer. The other is the world of Lou Ell, his modern counterpart. In this assembly, the changing face of Nebraska becomes a chronicle of the ages. THE END

50 NEBRASKAland

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . .

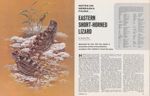

EASTERN SHORT-HORNED LIZARD

by Quentin Bliss Misnamed by man, this tiny reptile is diminutive version of its prehistoric ancestors. Evn habitat is much the same This month marks the fourth anniversary since Nebraska fauna have been featured in color. The series has now been expanded to include Nebraska flora as well. First is the Black Walnut, scheduled for the April issue. Following is a handy index to color fauna features since February of 1966: 1966 February -Leopard Frong March -Badger April -Channel Catfish May -Avocet June -Rainbow Trout July -Hummingbird August -Western Fox -Snake September -Mule Deer October -Ring-Necked -Pheasant November -Beaver December —Walleye 1967 February —Tadpole Madtom March -Blue Racer April -Wilson's -Phalarope May —Bobcat June -Largemouth Bass July -Crayfish August -Black-Footed -Ferret October —Muskrat November -Copperhead December -Cottontail 1968 January -Spade-Footed -Toad February -Bushy-Tailed -Wood Rat March -Spiny Soft Shelled Turtle April —Swainson's -Hawk May -Western Coachwhip June -White Bass July -Plains Killifish August -Dowitcher October -Gray Fox December -Mallard 1969 January —Mink Februar -Sparrow Hawk March —Black Crappie April —Ornate Box -Turtle May -Prairie Rattlesnake June —Northern -Grasshopper -Mouse July -Burrowing Owl August —Spotted Ground -Squirrel October -Prairie Chicken November -Black-Tailed -Prairie Dog December -Fathead Minnow 1970 January —Timber -Rattlesnake February —Prairie Vole March -Pintail April -Monarch Butterfly May —Johnny Darter June —Common Tree -Frog July —Striped Skunk August —Bobwhite Quail October —Brook Trout November —Common Water -Snake 1971 January -Sand Shiner MinnowHORNED TOAD is an incorrect, but persistent name for the eastern short-horned lizard, Phrynosoma douglassii brevirostre. This small reptile has a broad, flattened body. The back of its head, sides of its body, and tail are bordered by a fringe of short spines, commonly called horns, from which it gets its name. These spines have bony cores and are only slightly longer than they are wide. The tail is short and makes up less than a third of its total length. Unlike most lizards, the tail is not brittle and will not break off. Adults are usually three to four inches long.

Maximum length is 4V2 inches. This lizard is a shy, harmless creature, but its body characteristics give it a gruesome appearance. It has a gular fold, a thick layer of skin on either side of the neck behind the ears. Along each side of its body is a line of what are commonly called enlarged scales, even though they are not really scales. Through the process of evolution, these bonelike particles, which were separate plates attached to the bodies of the horned lizard's reptilian ancestors, have molded together to become part of the continuous layer of skin along its sides.

Since the short legs and heavy body prevent it from running rapidly, the horned lizard must depend on coloration for protection against natural enemies. The top of the body is a grayish brown with two rows of large, irregular, blackish spots. The underside is a creamy white. These colors blend well with the lizard's natural surroundings, causing many people to overlook the reptile.

The horned lizard is found in North Dakota, Wyoming, and the western fifth of Nebraska. It is one of eight species in the Anguidae family found in North America, and the only one in Nebraska. Fairly rough terrain with scant vegetation is the place to look for it. In this restricted Nebraska range, the reptile is locally common in certain areas of the short-grass plains in the extreme western end of the state. It has been observed in large numbers around fossil diggings near Agate and Hemingford.

This westerner is quite tolerant of warm weather and is active only during the warmest months. It is one of the first to hibernate in the fall and one of the last to emerge in the spring. Horned lizards are uniquely different from other lizards in Nebraska in that females do not lay eggs, but bear living young. Five to six youngsters comprise an average brood. Young are usually an inch long at birth. It appears that more than one brood can be carried at the same time, because one female examined had six young, ready to be born, and four large eggs. The average number of eggs a female carries ranges from 10 to 15.

Voracious, these lizards feed exclusively on insects during the day. Despite its ugly appearance, this small reptile is definitely on the side of the rancher because its diet consists mainly of grasshoppers and ants, two pests the agriculturists don't like. One remarkable aspect is that even a small lizard can swallow a grasshopper over an inch in length.

So, the next time you see this shy creature, remember that it is not a toad, but a lizard. All in all, it's a pretty good little critter to have around. THE END

53 FEBRUARY 1971

DESTINED TO DIE

(Continued from page 21)their promise, the central route's superiority would be established. Trade from the southern route would come their way.

It was a race against time.

Obtaining the mail contract in Janu- ary 1860, they laid out the entire 1,966-mile route in 65 short days. They bought 500 mustangs and Kentucky-bred horses, and hired 200 express agents and 80 jockey-like riders. They also set up 190 stations along the way, equipping each with saddles and supplies.

The famous run in which a mailbag was relayed from horse to horse from Saint Joseph to Sacramento in 9 days began April 3, 1860. The route entered present-day Nebraska at the Gage County-Jefferson County line, cut northwest to join the Platte River at Fort Kearny, and dipped to Julesburg. From there, it headed northwest again, past Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff National Monument, leaving the state where the North Platte River comes into Nebraska from Wyoming.

A rider whipped his horse at top speed for 10 or 12 miles to the next relay station, then jumped from the light saddle, scarcely touching the ground, to another waiting mount. If he had to stop, he could use only two scheduled minutes. In order to save time, the same saddle stayed with a horse as it was ridden back and forth between one relay station and the next. Only the mochilla, or saddlebag in which the mail was kept, was changed from horse to horse. Riders switched at home stations located approximately 70 miles apart. For the most part, they rode unarmed. Whenever they carried light guns, they did so without company approval.

The hectic schedule developed into military precision during the 18 months of Pony Express delivery. It caught the imagination of many young riders, torn between the lure of Civil War battlefields and the yen for excitement on the Pony Express trail.

One of the most dangerous stretches of the route lay through Nebraska Terrttory, where the U.S. Army was having difficulty protecting homesteaders as angry Indians attacked, hoping to keep the territory for themselves. But no matter how touchy the situation in each area along the Nebraska portion of the trail, the Pony Express went through.

One Nebraska rider, William Campbell, rode regularly between Valley Station 11 miles east of Fort Kearn£, to Box Elder Station 3 miles west of Fort McPherson. Although the riders were supposed to be at least 20 years old, Campbell was only 16. Like many other youths attracted to the Pony Express, he had lied about his age. Records compiled after the Pony Express ceased operation show that the average age of the riders was 19.

Campbell earned his place in the annals of history for staying in the saddle 24 hours on one run early in 1861 during the coldest part of the winter. A snowstorm had covered the trail with drifts, forcing him to use the tops of weeds along the trail as landmarks.

Campbell had other worries during his time on the trail. On one occasion he was chased by a herd of buffalo, and another time 15 or 20 wolves followed him several miles to the next relay station.

Throughout the duration of Pony Express delivery, only one rider was killed while on duty. Others died during outside activities. Melville Baughn, who rode to Fort Kearny from the east, was hanged as a murderer at Seneca, Kansas, several years after the Pony Express folded. Jim Beatley, who had the route into Nebraska from Kansas, was killed in a showdown in Jefferson County a year after Pony Express duty.

While these were some of the more spectacular incidents involving Nebraskans, the outstanding feats were those of bravery against the elements in order to make good the company's claim that nothing stopped the mail. Jack Keetley, riding to Big Sandy along the Little Blue River, once worked double duty for another rider, covering 340 miles in 31 hours without stopping to rest or eat. He was pulled from the saddle sound asleep.

While riders pelted across the prairie, the Pony Express attracted attention across the nation and evoked newspaper editorials. The San Francisco Bulletin echoed the thoughts of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, noting the venture's purpose was to establish the central overland route as the fastest link between East and West.

The Rocky Mountain News at Denver hoped it would "shame Congress into establishing daily or, at least, tri-weekly mail service across the West. Whether Congress ever admitted to shame would be a matter for high speculation, but it is on record that in the spring of 1861, a law was passed calling for bids to carry mail on a regular basis to the West Coast.

The Pony Express was riding high on the trail at this time, but Russell was in New York trying to get the government to pay some money due to him which he, in turn, needed to pay a company debt. A clerk in the federal treasury department obtained bonds worth $870,000 for Russell, but it turned out that they had been stolen, so Russell was arrested for possession of stolen goods. While he battled his way through the courts during the spring of 1861, John Butterfield, who operated along the southern route and was closely connected with the financial backers of Wells Fargo, got the mail contract away from Russell, Majors, and Waddell. He moved his coaches up to the central route, but knew he could not match the Pony Express for speed, so he signed a deal allowing the Pony Express to continue until completion of the telegraph line across the country.

With instant communication between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, the Pony Express was suddenly obsolete. Although it continued operating about six weeks after the first telegraphic message was clicked between Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, it was officially discontinued October 26, 1861.

Wells Fargo bought the Pony Express and its $200,000 deficit a short while later, another step in the company's

The last competitor Wells Fargo faced was Kentucky-born Ben Holladay, owner of the Overland Stage Line, but Holladay saw the handwriting on the wall as the railroad pushed west. He sold his holdings to Wells Fargo in November 1866 for $1,500,000 plus $300,000 in Wells Fargo stock. Before that, he had been forced to move his stage terminal from Omaha to Columbus, and then to Fort Kearny, giving way to the stealthy approach of the iron horse.

After Wells Fargo gained control of the stagecoach business, the company

54 NEBRASKAlandissued combination tickets allowing passengers to ride the train as far west as it went, then transfer to a stagecoach. But it was only a temporary arrangement, and when the twin bands of steel finally reached the West Coast, Wells Fargo eventually became a dormant firm, a subsidiary of American Express.

Relegated to history books since it was swallowed up by Wells Fargo, the Pony Express reappeared in Nebraska two years ago when the company, purchased from American Express by Baker Industries of Cedar Knolls, New Jersey, expanded its armored-car service to six cities in the state. Each armored car carries the original Pony Express emblem, a dashing rider in a diamond-shaped logo. Yet the days of those daring young men sweeping across the plains are gone forever.

While the reign of the Pony Express was short, it made an indelible mark in western history, a mark that will always be colored by romance and adventure reminiscent of the days when the frontier was being opened. THE END

BUSHTAILS IN AMBUSH

(Continued from page 35)positions a hundred yards apart. Each selected an area of scant undergrowth within shooting range of the unpicked corn. The monotonous drone of nearby corn pickers reminded the hunters of the providers of their day's sport. The weathered, leaning, corncrib up the hill would soon be filled to provide clever bushytails with a source of winter food. Green mulberry leaves from small saplings in the wooded drainage bottom littered the ground. An isolated day of Indian summer, clear and warm for early November, had been preceded by almost a week of rain and fog. It was an ideal day for the tree rodents to resume their busy schedule of fall tasks after the days of dampness. An early afternoon lull seemed to settle over the squirrels' movements, and the action slowed.

A gentle snap of cornstalk readied Jerry's .22 for action. Tense moments of expectation passed as he anticipated his second squirrel of the afternoon. Another asset to his revised form of still- hunting bushytails revealed itself as one of NEBRASKAland's "gray ghosts" emerged from the unpicked corn. Darkened swirls above the eyes marked the white-tailed deer as a harvestable trophy for next fall. Nibbling cautiously on low hanging browse, the semi-yearling never detected the concealed hunter only 15 yards away. As Gary crossed a fallen elm to join his partner, the snap of a branch sent the fawn back into the corn in high gear. Suggesting they abandon the sitting approach for the more traditional method of stalking, Gary led the way through the remaining half-mile of naked woods.

The squirrels' siesta apparently over, action picked up, reaching breakneck pace in the remaining wooded bottom. A scrambling double leaped precariously from branch to branch. Gary's .410 nailed one. A moment's pause spelled the end for another corn-fattened squirrel as Jerry's skillful shot upended the second twin. Somewhat grudgingly, Jerry bore the brunt of the hunt's success in his game pouch.

Pre-planning their gunning gear had restricted Jerry to his .22 auto-loader as Gary, somewhat disgruntled, conceded to hold up the shotgun duties with his .22-.410 over-and-under. Both hunters, being of the old school, were dyed-in-the-wool riflemen when it came to "squirreling", but they agreed one should carry a scattergun to test their new hunting method. A definite asset on snap shots between corn and timber or on tree-topping bushytails, the shotgun was somewhat less desirable on branch-hugging squirrels. A damaged rear sight made Gary's use of the rifle barrel of the handy little weapon less accurate.