NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

January 1971 50 cents TWO COLOR SPECIALS: BOYS TOWN AND STUHR MUSEUM ■ SPOONBILL CAT WITH BOW AND ARROW ■ HOW TO MAKE YOUR OWN CORNED MEAT ■ TOMBSTONE OF THE OREGON TRAIL ■ ANTELOPE A-BUCK-APIECE IN THE PINE RIDGE

Get Your New NEBRASKAland TOURAIDE MAP

For the Record...

ANTI-GUN LEGISLATION

During the past year, proponents of anti-gun legislation, for the first time, have been making open demands that law-abiding, private citizens, be stripped of their right to possess firearms.

It should be known and appreciated that the National Rifle Association, an organization comprised of more than a million American citizens, will continue to give the maximum support and effort within its power to uphold the constitutional right of law-abiding private citizens to keep and bear arms.

Although our principal interests are in educational and service programs for our members, we as individuals, in expressing our views on legislation, do no more than exercise our right to free expression guaranteed under the First Amendment —something that any citizen or group of citizens is clearly entitled to do.

The NRA has been wrongfully and unmercifully smeared in recent years by those who oppose our motives of patriotism and sportsmanship. It is a deliberate attempt to discredit us because we have dared to advocate the right of citizens to possess and use firearms for legitimate purposes.

Although some legislators now seek to abolish that right, no confiscation of private firearms can occur as long as NRA members and other firearms owners stand firm.

Through the mounting public pressure of gun owners and other citizens interested in constitutional government, the repeal of the harsh and unnecessary features of the enormously unpopular Gun Control Act of 1968 can now be anticipated. The Gun Control Act of 1968 is a legislative monstrosity saddled upon the people during a period of emotionalism.

The most objectionable features include those that make a law-abiding citizen subject to criminal penalties for doing nothing more overt or violent than failing, through oversight or ignorance, to comply with difficult-to-understand details of a lengthy federal statute and administrative regulations issued thereunder containing many provisions never contemplated by Congress in passing the act.

Any talk about substitute legislation should include the basic precept that it would be clearly directed at criminals, not legitimate gun owners. It would thus be an anti-crime measure of the type which should have been passed in 1968, instead of an anti-gun measure.

We perceive no need at this time for any registration, licensing, identification card, data retrieval, or certification law. Nor do we find need for any law prohibiting the sale or acquisition of target and sporting firearms in interstate or foreign commerce. There is no gun problem in this country that justifies such restrictive laws.

Freedom from arbitrary governmental interference is implicit in the concept of order and liberty upon which this nation was founded and which has made it the greatest in the modern world.

There is a crime problem and a problem of law enforcement, and the way to solve them is to enforce existing laws against criminal acts.

JANUARY 1971A New Year's Resolution

before you fire...first inquire

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.BETTER LATE-"I was 80 last September 1. I enjoy NEBRASKAland and save every issue. It is the only way I have of knowing what the other parts of the state are like. My one regret is that I didn't know about this good magazine sooner. But it is better late than never. -Mrs. Earnest Shoffield, Kenesaw.

IT'S A RAKE-"We enjoy NEBRASKAland so much. But, if you are a native Nebraskan or have ever lived on a farm, your face should be red at calling that side-delivery rake a plow in A Little Bit of Fall (October 1970). Beautiful pictures just the same."-The McDermotts, Broadwater.

NOT A PLOW - "On page 26 ofthe October NEBRASKAland, it says, 'a farmer plows his last lonely rim'. That is a side-delivery rake, not a plow." —Ed Sejkara, Burchard.

RAKED OVER —"I believe the farmer on page 26 ofthe October issue of NEBRASKAland (A Little Bit of Fall) is pulling a side-delivery rake instead of a plow." — A. J. Roelofsz, Alvo.

Our caption writer is now taking a crash course in farm equipment. — Editor. HOORAY FOR OUR SIDE-"My congratulations to Walt Meyer, assistant fisheries supervisor. "His article in the October issue of NEBRASKAland (Brook Trout, Notes On Nebraska Fauna) is the finest article I have ever read on that subject — clear, concise, to the point. Delightful reading. "I am rewriting my stories on Michigan trout. In my research I have found that the first brown trout in the United States did not come from Germany, but from England." —Harold (Dike) Smedley, Pompano Beach, Florida. REMEMBER WHEN - "I was born in Franklin County in 1903 and moved to Salem, Oregon, in 1937. I think I have fished and hunted almost every lake and stream in western Nebraska, including the Sand Hills lakes north of Ogallala. "We certainly enjoy NEBRASKAland, and would like to ask when your licensing began on fishing and hunting in the state," —Jacob Conboy, Beaverton, Oregon. Appropriate divisions within the Game and Parks Commission indicate that combination hunting and fishing permits were first issued in 1901 thus becoming the first state to do so. — Editor.SHAME ON YOU-"I have been a reader and subscriber to Outdoor Nebraska and NEBRASKAland for a number of years now. I have always enjoyed the magazine and have considered it to be a magazine for the entire family. I have also recommended the magazine to a great number of boys with whom I have been working in Scouting for the past 12 years.

"I have only one complaint. That is related to the October issue. Can you really afford to destroy your wonderful reputation by printing such slop as the attached cartoon?" — Elmer M. Schneider, Omaha.

The cartoon in question is reproduced below. — EditorSkiing is a Frontier Sport

Ski the Frontier Rockies. Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Here you'll ski some of the best conditions in the world. Frontier Airlines offers you a choice of 32 ski spots in the Frontier Rockies. From sunny Taos to Northern Wyoming's uncrowded slopes. "In" places, out-of-the-way places. Even the slopes that will host the 1976 Winter Olympics. We'll put you in a great skiing atmosphere even before you get to the slopes. Our Snow Club flights are made just for skiers. Special beverages. We'll also make your lodge reservations for you. Help you get transportation to the slopes. And fly your skis free as a second piece of luggage. In a protective bag. For more information, write to us for our special Frontier Ski Guide. Then let your Travel Agent send you to the Frontier Town to do the kind of skiing you want to do.

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 4)member of a flock of mallards along the Platte River in Cass County a few seasons ago. The bird proved not to be an albino mallard, but an all-white Muscovy duck. It had, no doubt, left some farmer's flock to fly with its wild brethern. Though hardly rare, the Muscovy was a very able flier, and also was very good eating." — J. H. Streight, Omaha.

Opinions vary, but the result is the same after a check with NEBRASKAland' s photo section and game biologists. While the snow goose on the October cover may not be an albino, it is impossible to gauge light reflection from the photo. Consequently, reader Streight's guess is as good as ours. — Editor.TO FIND A FISH - "Can you tell me where to obtain further information on the Lowrance Fish Lo-K-Tor (Sonar Search, October 1970)?

"My congratulations to you on a very informative magazine." —C. E. Hutton, North Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada.

For further information on the device, contact Mr. Jim Fish, Fish Carburetor and Tuneup Service Inc., 201 North 19th Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68508.— Editor.HORNED QUESTIONS-"We have a pair of great horned owls in our game refuge. They have been there for several years, though some people say they destroy wildlife. Others talk in favor of them. Could you give us some information on them and tell us if they are protected?" — Einar Anderson, Edgar.

According to our Game Division, unless you have penned birds or animals that are vulnerable, chances are the owls will not hurt game populations. Should they start on the penned species, however, they will continue. The big birds are not protected now. Proposed legislation may put them on the protected list. — Editor.FISHING JUG — "I noticed the piece in the last NEBRASKAland (Outdoor Elsewhere, October, 1970) on how to get fishing worms out of a can. Here is another way.

"Cut the side from a half-gallon plastic bleach container, leaving the jug together. If the worms are at the bottom, turn the jug upside down or on its side to extract them. To carry, just turn so the handle is up. The container will not tip in the boat or in the car, since the contents act as ballast." — Paul B. Pinnt, Denver, Colorado.

NOT SO —"Just today I picked up the August issue of NEBRASKAland and noticed your statement that the town of Circle City, Alaska, consists of only one building'. (Speak Up, August 1970)

"Not so! Circle City has a trading post-post office-restaurant, a school, a church, and the homes of about 50 people. Camping space and a few sleeping cabins are available at the trading post, and Mrs. Warren's meals are unsurpassed.

"Maybe some fine Nebraskans would like to make the drive to Circle City some summer." — James E. Morrow, College, Alaska.

MORE THAN ONE-"In one of your comments in the Speak Up section of your August edition, you stated that Circle City, Alaska, consists of 'only one building'.

"The preliminary census figures for 1970 show that Circle City has a population of 40 individuals, 10 white and 30 natives. Consequently, the combination of the 'one building', and the 60-degree-below-zero weather that can be experienced in Circle City should result in the most integrated community in the United States, as well as the most unsanitary. The merchants may even experience a run on their stocks of body deodorant and nose plugs this winter.

"Having a road constructed and maintained to the most northerly spot accessible by road in the United States, where one can only find 'one building', makes for a good story. But it does not quite square with the facts. Perhaps your source of information was laboring under an additional misconception wherein it was assumed that the populace of Circle City was housed, with the exception of the 'one building', in igloos which melt in the summer, and therefore cannot properly be called buildings.

"However, I am enclosing a copy of a recent photograph of the town of Circle City. Although the copy is not too clear, you can very readily distinguish the banks of the Yukon River and the village that is situated next to it. You will also note that there is more than one building. In fact, I count more than one dozen and that does not include outhouses. I can confirm the validity of the photograph, since during my last trip to Circle City (approximately two weeks ago) all of the buildings depicted in the photograph appear to be intact and in use. The exception was one of the larger buildings which had burned during the past winter. This building was in the process of being reconstructed.

"I think I can safely assume that there is still more than one building in Circle City, although it is possible that a great conflagration has reduced the number of buildings in the town to one since I was last there, and I have not heard of it. In that case, we had better make some room in Fairbanks for an immigration of people from Circle, or be prepared to satisfy their demands for body deodorants and other sundries, although I do not think that even this will ward off an entire winter's onslaught on the olfactory glands." —Lloyd I. Hoppner, Fairbanks, Alaska.

Unfortunately, the photograph which Mr. Hoppner enclosed with his letter was not suitable for printing. It did, however, reveal that Circle City has more than one building. — Editor.LUCKY WATER-"Our son and his family live on a small ranch about 30 miles southwest of Ainsworth. Each time we visit them, I admire the little river that runs near their house. The enclosed photo and poem tell the story." —Harley O. Smith, Norfolk.

SMALL TOWNS, PLEASE - "I, like the person who wrote the letter in your October Speak Up, would like to see more stories of the settling of small towns throughout the state.

"It seems as though most of NEBRASKAland's content covers Omaha, the Platte River Valley, and the Pine Ridge area." —Bernard Adams, Ponca.

NEBRASKAlandSURPLUS CENTER

Finest Quality Insulated Coveralls

Yancey Motor Hotel

DEAN HOHNBAUM, Mgr. NEW ROOMS AMBER LOUNGE GRAND ISLAND'S CONVENTION CENTER Call 382-5800 For Reservations "where people meet people" — at 2nd and Locust Street GRAND ISLAND, NEBRASKABRUSH WITH DEATH

LIFE WAS JUST a bowl of cherries for 10-year-old Ira Fazel III on that bright, spring day in May last year. The setting was ideal. Ira, his two sisters, grandmother, and mother and father were breaking in their newly built truck camper at the Louisville State Recreation Area.

The Memorial Day weekend was the first camping trip ever for the Lincoln-based Fazels, and everything was falling into place perfectly. Young Ira, or Trey, as he is nicknamed by the family, was fully enjoying the excursion.

A water lover, Trey was a very early bird on the beach and into the chilly water. A stay-close-to-the-bank, non-swimmer, Trey borrowed his sister's plastic air mattress. The inflated mattress made a perfect boat-type vehicle on which to play.

The tall cottonwoods swayed in the light breeze as a holiday spirit of relaxation prevailed throughout the recreation area. Laughing voices filled the air. Squealing children raced across the sand and through the water. Everything was perfect for the Fazels. It would have been virtually impossible for the fun-loving family to have sensed even the slightest warning that their world of happiness was soon to be crushed.

As Trey splashed happily, clinging to the air mattress in Louisville's largest lake, he inadvertently floated far away from his normal near-shore position. Suddenly he could no longer touch bottom. Trey cannot recall exactly what happened, but he remembers trying to climb onto the mattress. In his struggle, he lost his grip on the raft, knocking it away.

The tranquility of the area was shattered as Omahans Tom Castle and Julius Beslee splashed into the 20-foot-deep water where they had seen a small hand go down. The immediate area erupted in frantic excitement.

After what seemed like hours, the two Omahans dragged young Fazel from the lake. They laid him on the grassy bank and began immediate efforts to revive him by the backpressure, arm-lift method of artificial respiration. Emotions peaked as the men methodically worked to save the boy's life.

Meanwhile, Nebraska Conservation Officer Larry Elston of Plattsmouth had rolled onto the area for a routine patrol. Completely unaware of the tragedy that had begun only minutes before, Elston stopped to check with the area superintendent.

Word of the accident spread fast. Spotting the uniformed officer step NEBRASKAland

Elston wasted no time in climbing back into his car and getting to the scene. Upon arrival, the conservation officer's eight years of experience and training guided his moves. Elston relieved Castle and Beslee from what they feared was a hopeless task. With Elston in command, the threesome picked up the limp body, held it upside down, and forced water from Trey's lungs. Then, laying the boy carefully back down and into position, Elston began applying mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. As poor as the odds were, since a student nurse from Omaha who was also spending the day in the area had examined him and had found no trace of a pulse, it wasn't long before Trey responded to Elston's efforts.

Trey was rushed to an Omaha hospital and later transferred to Bryan Memorial in Lincoln. The following day he was listed in good condition. He was released the day after that.

Elated, the Fazels couldn't thank all those involved in saving Trey's life enough. Phase one of the youngster's adventure with water was over, but phase two was rapidly approaching. Acting on the doctor's advice, and with Trey's consent, the Fazels enrolled the boy in the next beginners' swimming class at Lincoln's YMCA less than a week after he was released from the hospital.

It was only natural that Trey be extremely apprehensive. However, JANUARY 1971 he faced the project of learning to swim with monumental courage. His instructor, Harland Johnson, aware of the boy's recent misfortune, worked carefully and tirelessly with him.

Slowly, Trey mustered enough courage to enter the water. With understanding and encouragement, Trey began to learn the fundamentals of swimming. Before too many lessons had passed, he was doing well. But, when the course ended, Trey didn't pass his final test.

Most would have quit at this point. But quitting was the easy way out. Trey enrolled for the next beginners' course. He kept up his courage, determined to learn to swim. As he developed his swimming fundamentals, they became methods, and his personal confidence grew by leaps and bounds.

The next camping trip for the Fazels was to a "dry" area. With no water, there was no swimming, and, consequently, no chance for a rerun of the first camping nightmare.

But Trey soon sold his family on his new ability to swim. As a result, the next outing was staged at the Fremont State Lakes.

The ordeal is now a closed case. A near tragedy on the last day of May was reversed through the efforts of Trey's fellow outdoorsmen. Time, determination, and courage gave Trey the avenue to say thank you to those who saved his life. He is saying it the best way possible — it won't happen again. THE END

Make a Date

HOW TO CORN GAME

Even poor cuts of meat become gourmet treats if given this treatment. Have the rye bread ready

12TO MOST PEOPLE, corned beef is a delicious, but expensive meat which is purchased in the grocery store and served with cabbage. How it is made seldom crosses their minds, remaining a mystery to them.

Like smoking and drying, corning has been used for centuries as a method of curing or preserving meat. The name is misleading, for the process has nothing to do with corn, but is said to come from Anglo-Saxon England when grains of salt the size of an English grain, which they called corn, were used to process the meat.

While usually associated with beef, corning is an excellent way to prepare wild game such as deer or antelope. A tough, or strong-tasting cut, can be turned into a fine meal. Any piece of meat may be corned. It is not necessary to have a top-grade cut or brisket — plate and flank are most commonly used. Because the corning process takes 15 days, it is advisable to do several pieces at one time. Once corned, the meat can be preserved if kept in a cool place. This recipe will make about 2 gallons of marinade, which is sufficient for 8 to 12 pounds of meat.

- 1 1/2 cups salt

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 2 tablespoons pickling spices

- 1 teaspoon whole cloves

- 1 teaspoon peppercorns

- 3 bay leaves

- 3 1/2 teaspoons sodium nitrate

- 1 teaspoon sodium nitrite

- 1 teaspoon onion, minced

- 1 medium garlic clove, minced

- 1 medium lemon, sliced

- 7 quarts warm water

First, mix all dry ingredients in a large crockery, plastic, or porcelain container. Do not use a metal container, because the chemical reaction can be harmful. Sodium nitrate and sodium nitrite can be purchased or ordered at most drugstores. Next, stir in the warm water. When all dry ingredients are dissolved, add the onion, garlic, and lemon. The meat is then added and should be completely submerged in the marinade. Cover the container and place it in the refrigerator. Every other day, the meat should be turned and the mixture stirred. After 15 days, the meat will be corned and ready for cooking.

If you wish to store some of the meat, transfer it directly from the marinade to a plastic bag, retaining some of the liquid. Squeeze all of the air from the bag and seal. Refrigerated, the corned meat will keep for several weeks, or it may be frozen for longer periods of storage.

To cook corned meat, first wash it under the tap. Place it in a pot and cover with water. Bring the water to a boil and remove the scum which forms on the surface. Then lower heat to a simmer and cook for four to five hours until tender. Potatoes, carrots, onions, and cabbage wedges may be added toward the end of the cooking period. The meat should be carved while hot, cutting across the grain in thin slices. Mustard and horseradish accent the flavor of the meat, and rye bread rounds out the meal. THE END

NEBRASKAlandNEBRASKA INTERNATIONAL SPORT SHOW

FEBRUARY 10-14 * FEB. 10--C0NWAY TWITTY&HIS TWITTY BIRDS HOMER & JETHRO * FEB. 11--HOMER & JETHRO * FEB. 12--DANNY DAVIS & THE NASHVILLE BRASS HOMER & JETHRO * FEB. 13 - SERENDIPITY SINGERS HOMER & JETHRO * FEB. 14-HOMER & JETHRO Plan ahead for this year's vacation and recreation time by attending thegreat, all-new Nebraska International Sport Show. Hundreds of displays featuring travel, boating, fishing, camping, recreational vehicles and more will put a wealth of information at your finger tips. There are lots of prizes for you, including an opportunity to win trips to Grand Ole Opry or the Big Red football game in Honolulu. Bring the whole family and enjoy a unique experience. PERSHING AUDITORIUM-LINCOLNAS CLOSE AS YOUR PHONE AS NEAR AS YOUR MAIL BOX

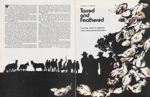

Tarred and Feathered

Incurring wrath of vigilantes often meant painful retribution

WIDE-EYED AND trembling like a nervous stallion, the prisoner watched every move his captors made. Masked, with their faces blackened in disguise, 15 men hurriedly raked wood together for a fire while others hoisted a huge cast-iron kettle onto a stand above the wood. Almost as soon as the last stick of kindling was in place, a torch was touched to the wood. A blaze soon raged below the pot.

Bound to a tree like a helpless animal, the prisoner watched as hunks of solid tar were thrown into the pot as a single captor began prodding and stirring the mixture with a long pole. Simultaneously, a large bag of feathers appeared from nowhere and was set beside the now-bubbling tar.

Glancing around at the black and lifeless storefronts of the frontier town, the prisoner scanned every crevice for signs of help. But the village was deserted. There would be no salvation from the deed at hand. With his last hope exhausted, the prisoner slumped against the tree awaiting his punishment. Reflecting on the past week, it was hard to realize that such a punishment would be meted out for his violation. All he had done was publish the truth in what his tormentors called his "radical rag". After all, that was supposedly his right —to print the truth as he saw it.

Minutes dragged as the prisoner watched the fire grow, fed by ever-larger chunks of wood and prairie hay. The tar was smoking now, the steam rising from the pot carrying an acrid stench through the autumn air. How long must he wait? What would it feel like? The questions raced through his mind as the odor of burning tar became stronger.

Answers were soon at hand. The cord holding him to the tree was cut and he was pulled toward the bubbling pot. Unceremoniously, six men dipped buckets into the frothing mass. Without further ado, they dumped the oozing liquid over the helpless victim's head. Scalding hot, it ran through his hair down his face and neck. Breathing became more and more difficult as the thick liquid invaded his nose and mouth. Down and down it came, soaking into his clothes and searing his skin.

With the tar applied, one of the vigilantes broke open the bag of feathers, lifted it up and sprinkled them over the tar. Their job done, the men backed away from their victim, now writhing on the ground in agony. And, almost as though they had never been there, they retreated, leaving only the tarred-and-feathered body behind them.

Such were the instances that spread across the plains as a deterrent to any charlatans or con men who might try to take the settlers for their worldly possessions. Yet, tar-and-feathering ceremonies were by no means reserved for lawbreakers. Anyone who went against the desires of the community was liable for a taste of tar and feathers. One minister in the Hastings area, a real fire-breather, preached the wrath of God and the fire and brimstone of damnation once too often. His flock ran him out of the country and made it quite well known that if another of his breed were to replace him, they would be only too happy to tar and feather even a man of the cloth. Fortunately, the next preacher must have filled the bill, because there is no record of an encounter with the sticky stuff.

The punishment was a holdover from the past, even in the early days of Nebraska. As the melting pot of the world, the United States found all sorts of punishments woven into its basic structure — tar and feathering among them. It was, however, primarily confined to the eastern (Continued on page 61)

TOMBSTONE OF THE OREGON TRAIL

Chinmey Rock is marker to pioneer trails, tribulations

NEBRASKAlandMORE THAN A century ago, some 250,000 pioners had already followed what was known as the Oregon Trail, and had struggled past Chimney Rock in covered wagons. The land has all but reclaimed the ruts of that long trail, as it has the estimated 6,000 graves strung out along its length.

Looking down into the wide Platte Valley from high on the slope of Chimney Rock, owned now by the Nebraska State Historical Society, one can almost see a mirage of those ox-cart caravans, and the ghosts of these travelers who paused to wonder at this abrupt spectacle. Warren NEBRASKAland A. Ferris in 1830 called it "a singular mound... shooting up from the prairie in solitary grandeur, like the limbless trunk of a gigantic tree."

In a century of highway travel, when landmarks mean little and command minutes — not days — of our attention, it is difficult to recapture the significance of a feature such as Chimney Rock. But the journals and diaries that remain from those journeys attest to the remarkable hold the Chimney had on the pioneer. Along with Independence Rock and Scotts Bluff, it was one of the most important landmarks of the trip across the plains, for almost without JANUARY 1971

For some 90 miles, or 4 days' travel, Chimney Rock was on the pioneer's horizon, holding his interest and wonder. It meant to him a good campsite with plenty of grass and a cold stream. More importantly, it meant that the endless tedium of the gentle, grassy sea was ending. He was cheered by these sudden, surprising bluffs that appeared — long-needed diversions for the eye after JANUARY 1971 weeks of blank horizons. But as a curiosity, it refreshed his disposition for a moment only. As he saw in the night sky this stark silhouette, he knew what lay beyond —desert, mountains, and hardship, where the sun burned like a fever on the land.

Difficult as it might be for us today to gain an accurate historical perspective of Chimney Rock, the pioneers themselves were even more confused by the sheer physical perspective of this new land. It was a standard procedure, as this strange monument moved into view, for the more adventuresome of the caravan to leave the wagons and strike out ahead to explore the rock. They invariably underestimated the distance, owing to the magnifying effect of the clear atmosphere and the rolling prairie. What seemed a few hours' journey turned into a lengthy ride lasting as long as a day, and sometimes more.

Lack of any familiar reference also made for some startlingly inaccurate (Continued on page 57)

19

by Lowell Johnson A BUCK APIECE

Butte-country pronghorns are lessons in stealth and in stamina

20SQUINTING THROUGH the window of the station wagon at a whitish spot far off in the hills, I looked at what appeared to be a salt block, but I hated to pass it by without a closer look.

"Is that an antelope?" I asked. "Sure it is. Don't you know an antelope when you see one?" said Cecil Avey, Game Commission game warden from Crawford, who was on this off—duty jaunt with us.

Sure enough, it was. Three sets of binoculars confirmed Cecil's immediate identification. It was a lone buck, taking his ease in the sun, reclining in a rocky washout near the top of the highest hill in the territory. While we peered through the binoculars, a small herd of (Continued on page 61)

NEBRASKAland

City of Little Men

Home, school for 1,000 boys this state original numbers its alumni, fans in millions

WHEN I WAS still a sprout, our family was traveling through Nebraska to our home in Missouri. Somewhere along the way, Mom must have seen a sign, for she would have it no other way. (Mothers are like that, sometimes.) We had to detour 50 miles out of our way to see a place we had all heard about, but had never seen — a place called Boys Town.

Like many other Americans, we had seen Spencer Tracy recreate the role of the compassionate Irish priest with a dream about a home for unwanted boys, and had received the 'He ain't heavy, Father. He's m'brother" stamps in the mail every Christmas. Like so many others before and since, we had heard the world-famous Boys Town choir. Now, being so close, we had to see "Father Flanagan's place" for ourselves.

Just how many travelers have done exactly the same thing over the years is impossible to tell, but they must number in the millions. While not intended as such, Boys Town has become one of NEBRASKAland's top attractions.

Surely, everyone treasures the heartwarming story of the young priest whose dogged determination created a home for the homeless. His almost single-handed triumph despite overwhelming odds has become a legend of the 20th Century. And, the late Father Edward J. Flanagan has taken a place among such greats as William (Buffalo Bill) Cody, the most famous and loved Nebraskan of all time. No fictional hero could surpass the true-life adventures of the founder of Boys Town.

Many changes have occurred since Father Flanagan opened the doors of that first home on the corner of 25th and Dodge in Omaha on December 8, 1917. Just six months later, new quarters were obtained at the 'German NEBRASKAland

But one thing has not changed —the reason for its existence. Now, as then, the welfare of the boys comes first. Boys Town is home and school for some 1,000 homeless and underprivileged boys, regardless of their race or creed. It is more than brick and mortar or classrooms and shops. It is a living monument to love, devotion, and dedication, projected into the hearts and lives of the boys who call it home and its more than 12,000 alumni.

Contrary to some opinions, Boys Town does not generally deal with the delinquent boy. Rather, its program is a preventive one. Certain standards and qualifications must be met for admission. A child must be homeless and must come from a community with no program to offer. He must be at least 10 years old and capable of doing fifth 26

Recommendations for admittance come from many sources —relatives, friends, priests, ministers, juvenile courts, and social welfare agencies. Unfortunately, there are about 10 times as many applicants each year as there are openings. Consequently, requests for admission must be carefully screened to make sure the boys accepted are those who will profit most.

Once admitted, nothing holds a boy there—except his own will to stay. It is not an "institution", and there are no gates, locks, or fences. Of course, every youngster is required to attend school, and subjects taught are much the same as those offered in any other school. The vocational-education program offers training in many useful trades.

Some 50 buildings shelter myriad and varied activities of this bustling little "city", housing everything from a post office to a herd of 100 registered Holsteins that produces 600 gallons of milk a day. (The boys consume about half that amount.) In fact, the boys raise much of the produce that goes onto their menus. Guests can sample the fare at the restaurant in the visitor 30 center, which also houses a small but interesting museum and souvenir shop.

Study, work, play —all are part of daily life at Boys Town. When day is done, the boys bed down in attractive cottages nestled in the rolling hills where a small lake enhances the rustic tranquility of the area. A beautiful chapel, which received a facelifting about three years ago, offers solace of another sort.

Whether playing basketball or learning a trade in the shops, whether wrestling in the gym or gathered together for chow, the citizens of Boys Town know they have found a home where they enjoy love, care, and respect, some of them for the first time in their lives. It is a uniquely warming experience to see these lads as they go about their daily routines.

A few years ago, we drove 50 miles out of our way to see NEBRASKAland's Boys Town. It was a detour I'll never forget. Today, the 50-mile jaunt from my home in Lincoln to the City of Little Men has become a regular highlight of my itinerary for visiting friends and relatives. Each visit reaffirms the fact that man can change the unjustices he sees. THE END

NEBRASKAland

Undressed for 35 cents

Youthful venture gets unique twist as two sprouts take on nature's perfume factory in episode that smells of profit

CHARLIE BAKER and Jimmy Fisher spent the early years of their youth practically as brothers, living on adjoining farms near Wauneta and attending the same country school. At 10 years of age they decided to earn some money. Both wanted bicycles, even though they had ponies.

One day they were sitting on a fallen log that spanned the Frenchman River, discussing what to do. Charlie saw a beaver dart through the water. "Hey, let's trap," he said. "If we can get a couple of beavers we can buy us each a bike." "Yeah, let's do," said Jimmy.

The boys had often gone with their fathers to set mink and beaver traps along the river. Some hidesdressed — brought as much as $40. Each of the boys had hoarded an old, rusty, discarded trap that had belonged to his father.

They ran to get them, dragged them to the river, and set them on the bank. "Ask your ma if you can stay at my place tonight," Charlie said. "We can sleep in the haymow and get up early to see to our traps."

But neither boy woke up until Charlie's mother called them to breakfast. They ate their fill of flapjacks, JANUARY 1971 washed down with plenty of fresh milk, then headed for the river. Charlie's trap was empty, but Jimmy's held the remains of a very unlucky skunk.

The boys looked at it quietly for awhile. Then Charlie said: "Why don't you sell it to old Deke. He'll pay you 35 cents for it." Teah, but pa got $4 for one he dressed," said Jimmy. 'Why don't you help me dress it and we'll split the money."

First they removed the skunk from the trap with no more casualties than a few broken fingernails and a bruised thumb. The next task was to remove the pelt. Though the boys probably didn't know it at the time, that animal was about to pose more problems for them than they could have ever imagined possible.

Jimmy said they must lay it on its back on a board or log (just as he had seen his pa do) and slit it dowTn the middle to where the tail connected. Then they must cut it down each leg and leave the paws.

Charlie whipped out his pocket knife. As they struggled to cut the skin they visualized their trophy nailed to the side of the shed, curing in the sun. But, when the knife proved to be too dull, Charlie ran to the house and sneaked two (Continued on page 61)

33

SHADOWS IN THE RIVER

Record spoonbill falls to bow-bending brothers in Gavin's Point Patrolling shallow water slicks yields mixed catch

THERE IS SOMETHING alive about the river. Unlike a lake or marsh, it is never static. It always moves. It seems to be hurrying to a distant meeting with the sea. When you grow up near the waterway you come to know it. There is the shroud of fog in the pre-dawn light, the beaver slipping off the muddy bank, swimming against the strong current. There is the placid surface, which can turn to treacherous, frothing waves in a minute, and the cove in the lee of the island where the great blue herons wade at dusk. When you grow up on the river it becomes a part of you.

John, Jr., and Jeff Schuckman are growing up on the river. From its birthplace in the mountains of Montana, the Missouri meanders across the plains of South Dakota and alongside Nebraska. Some 10 miles north of Crofton it is slowed by Gavins Point Dam, which backs up the water to form Lewis and Clark Lake. Slowed, but not halted, the river tumbles through the dam and flows on. John's and JefFs home is a mile below the dam where the water still churns with the energy of its release.

Summer means many things to many people, but to the boys it means the river; NEBRASKAland

It was early in the summer of 1970 when I learned from the boys' father, John, Sr., a Nebraska conservation officer, that they had taken several paddlefish with bows and arrows the previous summer. Being an amateur bow hunter myself, I asked him to contact me when they started hitting paddlefish again. The call came in mid-July, but it was almost a month before I was able to get away

Arriving at the Schuckman home late that August afternoon, I met John and Jett. John is 15 years old, stocky, and has sandy red hair. Jeff, at 14, is almost a match for his brother in size. John had already collected two state archery fishing records during the summer, one for gar and one for paddlefish, and was anxious to get to the river to try for another.' Minutes later we were loading our gear into their wide-beam, 16-foot pram.

"We don't have too much time before sunset," John said, as he cranked the 18-horse

motor to life.

"Why don't we try the holes downstream?" Jefl suggested. That way we can leave

JANUARY 1971

35

Several miles downstream we rounded the tip of an island, sending a flock of 20 blue-winged teal skyward. Farther downstream we came to the first hole. John slowed the boat. The "hole" was actually a large, shallow-water slick near the center of the river.

"Paddlefish lie at the bottom of these slicks to feed," Jeff said. "We run the boat around for awhile and try to spook them up." "Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't," John grinned, as he twisted the throttle.

As we started up the slick, Jeff knelt near the center of the boat, his bow poised. Both John and Jeff shoot 45-pound, wood-and-fiberglass-laminated, recurve bows. The dark outline of a fish appeared momentarily about 10 feet from the boat. Jeff drew his bow, then lowered it without shooting. "Just a carp," he said. "How could you tell?" I asked. 36 NEBRASKAland

Large schools of carp and buffalo were feeding on the surface all around the hole, but several more passes revealed nothing that resembled a paddlefish. "Shall we shoot a few carp?" Jeff asked, as we finished a sweep. "It's getting late," his brother answered. "Let's try one more hole downstream. We can always get carp or buffalo on the way back."

The second hole produced nothing —not even carp or buffalo, and John speculated that another boat may have worked the area. John explained that they do almost all their bow fishing during the week. "The fish just seem to vanish during the weekends when there's so much boat traffic."

The sun, balanced on the horizon, cast a yellow glow over the river as we returned to the first slick. Jeff suggested we try a few more paddlefish runs before going after carp or buffalo. We reached the head of the pool (Continued on page 56)

JANUARY 1971 37

THE MILL AT CHAMPION

After grinding away since 1886, this old Nebraska business has earned its new role as historical park

DOWN BY THE OLD millstream, where I first met you...and everybody else in town. The picturesque old mill was never, even in its heyday, a place of solitude. It was the backbone of the economy in a pioneer community — a natural gathering place.

Champion Mill in southwestern Nebraska was no exception. Today Champion Mill is the only water-powered mill still operable in the state, having served the community for 77 years without pause. Recently acquired by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission as a state historical park, it will, in time, be restored as much as possible to its original condition.

The mill at Champion was built in 1886, when the town was still called Hamilton. Champion legend has it that rock came from the old Rock Corral which belonged to an even more ancient time than the mill. The old stone structure is rumored to have been used by local cowboys while rounding up cattle. By the time the mill was built, however, it had fallen into disrepair, and was being dismantled, for rock was a rarity on the plains.

Construction of a mill was the making of many a pioneer community. It was here that the farmer's grain was turned into meal or flour to feed his family. Here, rumor and gossip were exchanged and political views aired. Mills encouraged the settlement of some communities which later grew into larger cities. The presence of a mill encouraged other industries to locate nearby, for the mill's clientele could be lured to the other businesses when their milling was finished.

Mill day was a big day for farmers as they hitched their horses to a wagon that would take their grain to town. Hauling grain was often the business of the eldest son, and a sober responsibility it was, too. For all families liked to eat, and flour was a basic necessity.

But milling day was not all business. The millpond had recreational attractions, too.

In the dry summers on the plains when irrigation was almost unknown and underground water untapped, any water was a drawing card. If a stream of any consequence were dammed, then the resulting lake, no matter how small, was going to attract people. At the time, the Frenchman and Republican rivers were the only major sources of water in the south-western part of the state. The dam on the Frenchman 38 that formed the millpond at Champion was a center of social activity for the entire area.

In hot weather, the millpond was a cool swimming hole; in winter its surface was a smooth ice-skating surface when other ice surfaces were wind-rippled, and too rough. The mill burned one winter in the early 1890's, and a lot of skates and winter wraps, stored inside, burned with it.

In 1893, it was rebuilt and renamed the Lakeside Roller Mill. It has been in continuous operation since. During the 1920's and 1930's the millpond was equipped with a diving tower and 200 to 300 people would gather there on a Sunday afternoon to frolic in the little lake's refreshing water. In those days, the Frenchman River was crystal clear and the millpond was 15 to 20 feet deep.

Time has worn the structure's exterior, making repairs necessary. Presently, a large portion of the outside is covered with corrugated tin. Future development plans include replacement of that exterior with new weatherboarding. The tin roof will be replaced with wooden shingles, and a new paint job is being planned. The Game Commission will shore up flooring to allow for more visitor weight. More safety railings will eventually be installed.

Spinning gears and slapping belts run a long series of operations throughout the mill. A shaker separates grain from bits of debris by sifting it through a fine screen, designed to take out small sticks, bugs, and straw.

Wheat was separated from chaff here, and ground into the light, powdery flour so essential to baking.

Grain, then flour moved through the structure by a series of "conveyor" belts, wide leather belts fitted with cups that scooped up grain or flour, and carried it upward into the mill proper. All-wood casings still enclose the conveyor system. The same wooden ducts carried flour down to be bagged and weighed. Carved wooden valves slid through slots to cut off the flow.

Additional Game Commission plans call for making cutouts of the duct system and filling the gaps with glass. Some sort of brightly colored material will be run through the various milling processes.

Turning from the clatter and bang of second-floor equipment, visitors will be able to peer through rough-hewn windows at (Continued on page 57)

NEBRASKAland

PIONEER'S VISION

Born of namesake's dreams, Stuhr Museum is key to the past for those who enter its lofty portals

TAKE THE VISION of a prairie pioneer and the plans of an imaginative architect. Add a certain amount of capital and the backing of a community. Put them all together at the right time in the right place, and you have a unique and beautiful structure on the plains-in this case, a museum.

Add a hard core of dedicated people, willing to extend themselves to carry out the wishes of the pioneer's vision, and you get much more-a museum with warmth.

Many museums seem designed as much for the ghosts of yester-year as for the present generation. They are often cold, gray structures boasting little more than the drabness of death or the memory of nearly forgotten relics.

But Grand Island's Stuhr Museum is different. From the moment you step inside, you feel as if you belong here, probably because of the extraordinary efforts that have been put into this complex.

The pioneer with the dream was the late Leo B. Stuhr, who left the bulk of his estate for construction of the museum he dreamed of for many years. The architect was Edward Durrell Stone of New York, commissioned to design the museum after Stuhr's death. The capital used to maintain the museum was a two-mill levy against the taxpayers of Hall County. The people approved such a levy because they were dedicated to a principal of preserving their heritage. People

Four of these workers are worthy of special mention: Mrs. Carol Echternach, Maynard Boltz, and Carl and Viola Ewoldt. Mr. and Mrs. Ewoldt were employed by Stuhr for 26 years until his death in 1961. Mrs. Ewoldt, with the museum since its beginning, decides how the displays are to be rotated, and how the antiques the museum still has in storage are to be presented when they are brought out.

"Our purpose is two-fold," states Jack Learned, museum consultant, "first to educate people, and second to make the public feel welcome."

Completed in 1967 and officially opened July 31 of that year, the village beyond the moat is the part that will continue to grow. The complex is situated on a total 267-acre area. The village lies on a 125-acre tract, which is being seeded with native grasses to provide background for the 42 buildings already on the site. Thus far, 15 of these structures, remnants of the first half of this century, have been restored. The others will be refurnished as research and finances permit. Approximately 80 percent of the museum's possessions are still in storage. But many of these items will go on display as buildings are transformed from broken-down shacks to authentic 19th-century businesses and homes.

Proof that the atmosphere of prairie hospitality attracts people is in the attendance figures. More than 100,000 visitors have toured the facility during the period since its opening. A description by one of those visitors was: "It's open and clear and easy to understand things here." That's what the people who follow Stuhr's vision like to hear-what drives them to keep the museum lively and friendly. THE END

46 NEBRASKAland

Blazing the Blue

When deer in the new unit came under fire, we were right there. Since then, we just try to stay smarter than game

DEER HUNTERS in southeastern Nebraska led a pretty dull life for half a century. There hadn't been an open deer season since 1907. Then, about 15 years ago a few white-tailed deer moved in along the rivers. Since then, they have moved up smaller creeks and draws. Even now, the deer population is not large compared to the rest of the state, but it has grown to huntafjle proportions.

When word got around that there would be an open season in 1961, two friends and I applied for and received three permits.

The newly opened area was named the Blue Unit after the Big and Little Blue rivers which flow through it. The Blue was one of the largest units in Nebraska, yet it had the fewest permits — 250 — and only deer with a fork on one antler were legal. With the addition of this area, the entire state was now open to deer hunting.

None of us had much experience with deer. Merle Colgrove, a farmer at Odell, had hunted mule deer in Utah about 15 years before, but Utah is a lot different than southeastern Nebraska. I had seen a picture of a deer once on a calendar.

Still, ours was a good group. We had hunted together for many years. Merle was our chief strategist. Because of the way he hunts, one would believe he is a cross between a coyote and an Indian. He specializes in coyote and quail, considering deer just a sideline. Duane Colgrove, Merle's nephew, also from Odell until recently when he joined the U.S. Army in which he is now a company commander at El Paso, Texas, is a wiry little cuss. He stands 5 feet, 7 inches and weighs 145 pounds. Frank Husa, also a farmer at Odell, goes after all small game, but has never tried the big stuff. He goes along on deer hunts (Continued on page 54)

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . SAND SHINER

Often found in deep pools which have considerable current, this species is one of the most adaptable fish of the state's myriad waterways

THE SAND SHINER, Notropis stramineus (Cope), is probably one of the most common minnows in Nebraska, and is found in almost all streams, lakes, and reservoirs, particularly those having a sand or gravel substrata. They exist from Wyoming and Montana, east to the St. Lawrence River, and south to the Ohio drainage system and Mexico.

The genus Notropis, collectively known as shiners, contains more species than any other group of freshwater fish.

Of the 10 recorded in Nebraska, two — the silverstripe and the silverband — have been recorded only once, the former in Lewis and Clark Reservoir in 1957, and the latter in an early-day Missouri River collection at Sioux City. In addition, the Topeka and blacknose shiners, while never common in Nebraska, are distributed to a very limited degree within the state, and possibly no longer exist. This is particularly true of the Topeka. Another, called the common shiner, is not common at all as its name suggests. In fact, its status in Nebraska is doubtful.

The remaining four shiners —the emerald, bigmouth, river, and red — are quite common throughout the JANUARY 1971 state, with the emerald being found mostly in the eastern third of Nebraska.

The sand shiner has a moderately stout body and large eyes. The dorsal and anal fins generally have eight and seven fin rays respectively. Coloration is tawny to olivaceous dorsally, with silver sides and belly. There is a narrow mid-dorsal stripe that is intensified with a black dash within the base of the dorsal fin. The lateral line scales are marked by paired dark flecks near the pores.

There are no breeding colors to aid in identification, but the males possess tiny, hardened skin projections, called tubercles, on the head, which are difficult to see.

Nebraska and Kansas breeding seasons are from April through August. Wyoming records indicate a July-through-August spawning period. They apparently spawn over sand or gravel areas. This protracted reproductive period may be an important adaptation to life in prairie rivers, where flow volume varies widely.

Common as the sand shiner is, surprisingly little work has been done on its life history.

Adult maximum length is seldom more than three inches, and most generally less than two and three-quarters inches.

Little is known about feeding habits, but the sand shiner is generally regarded as carnivorous, although it can become omnivorous, eating both aquatic animal and vegetable life as each becomes available. In general, shiners are capable of modifying their feeding habits, thus avoiding serious food depletion by competition or other factors. The more specialized species appear to be subjected to considerable variation in numbers, depending on the availability of food and the number of competitors in the stream.

In all streams, the sand shiner has a habitat preference, since it frequents deeper pools with considerable current, apparently avoiding quiet pools or heavily vegetated areas. In silty streams, the sand shiner can be found in riffles or fast water where the swifter current keeps the bottom free of debris.

Like many other minnows in the genus Notropis, especially because of its prevalence, the sand shiner is an important forage fish for larger game species and often ends up as bait in the sport fisherman's pail. It is an important part of gar, dogfish, pike, bass, walleye, perch, and crappie diets. Without the presence of the minnows, these carnivorous fish would be forced to feed on their own young. A good population of forage fish is essential for maintaining a healthy population of desirable game species.

The minnows are unsurpassed as bait. However, they are rather delicate and die quickly in the minnow bucket or holding tank unless a supply of fresh, well-aerated water is furnished. Literally millions of minnows are wasted annually through careless handling. While the situation has improved in recent years, there is room for still further improvement. Minnow loss by anglers can be diminished with frequent water changes, and keeping the bucket away from the direct sunlight on a hot summer day. Several types of minnow buckets are specially designed to keep the bait alive and are well worth considering.

Most Nebraska streams are characteristically sandy, and it appears that ample habitat is available to insure continued presence of the sand shiner. This means game fish will continue to have an adequate natural food supply, and fishermen will continue to be able to obtain live bait for their sport. THE END

51

THE TOUGH BREED

Modern-day pioneer spirit is carried on by housewife when husband is hurt

ONE SEGMENT of Nebraska's population lives midway between the sophistication of urban centers and the down-to-earthness of farms. These are people who, although they are not farmers themselves, rely on agriculture for their livelihoods and carry on pioneer traditions and ethics. A prime example is Katherine (Kate) Bridgmon of Barada, a female mechanic and welder.

One of the traditions on the plains, before the development of social security, old-age pension, and Medicare programs, was that the sick were cared for by their own. When a husband fell ill, his woman continued the work, manly as it might seem, to sustain the family and keep it together. The pioneer woman was of a tough breed, feminine but not frail, who dedicated herself to labors of love when she married. It was this dedication, along with a will to survive, which toughened her and prepared her for most any crisis.

This is the tradition Kate followed, and which kept her going after her husband fell victim to an industrial accident in 1955. It was she who nursed him, who continued to care for their two young children, who continued with the cooking and housework, and to top it off, who helped with the business he started a year later.

Born in Hiawatha, Kansas in 1929, about 30 miles from Barada, she was reared in a home in one of Hiawatha's two cemeteries, where her parents (Continued on page 56)

TRAVEL TIP OF THE MONTH

Built in NEBRASKAland

Go-Lite CAMPERS

BLAZING THE BLUE

(Continued from page 48)just to drive the car and watch the action. Frank is 75 years old but can still out-walk, out-shoot, and out-cuss all three of us younger fellows. I, too, was an important member of the party, as I took pictures after the game was bagged. That's the way our party stacked up in 1961, and that's the way it was every year until I moved from the area.

For a bunch of beginners, we didn't do badly that first year. We got two bucks — big ones. The first field dressed at 210 pounds and the other was just a bit smaller. They were old, the product of years of closed seasons. Being past their prime, they had small, compact antlers with many points.

A year later we were a little wiser, and there were more deer. We scored three for three. Two bucks were identical beauties. Each had four points (western count), and the third was a sizable deer with three points on a side.

In the next few years, after our experience and studies of how hunters in other parts of the country go after deer, we devised a system. Southeastern Nebraska is mostly farmland. Much of the corn and milo is harvested by November, but that which remains provides excellent cover for deer. Whitetails are found mostly in the timber along creeks and rivers, and in draws which run into the uplands. Timbered areas are not large, but there are always avenues of escape since the cover is often dense.

Big deer drives, so popular in many areas, have never been used here. Even if a small army could be organized, there would not be enough bucks in an area to make the drive worthwhile. Also, while we were able to drive does wherever we wanted them, the bucks circled back, held fast, or mysteriously sneaked out through a back door. Some hunters kill deer by waiting in tree stands over trails and feeding areas. It might be productive, but we simply did not enjoy sitting around in a tree getting cold and stiff.

Our method was a cross between stalking and small-scale driving. We entered the cover from different sides, sealing off escape routes. We moved along quietly and slowly as if we were hunting alone, except that we met at a predetermined point. Usually one of us got there ahead of the others and took a stand, hoping the others would put a buck into motion. While we beat the brush, Frank usually sat on the road and watched the deer run out. Now, whether Frank actually saw all those deer or not I don't know, but he always pointed us toward likely spots and did a great job of keeping our enthusiasm high.

We learned the hard way that the presence of does doesn't necessarily mean bucks are in the area. Even though they exist in a 50-50 ratio at birth, we saw a dozen does for every buck. Bucks spend the day well hidden in the heaviest cover while the less cautious does readily expose themselves in the uplands. Does can be driven into the open but the bucks will circle back and stay in NEBRASKAland the brush. At least this is the way we thought it was.

Rifles were a different story, though. Here was something we knew about. We started out with brush rifles-.30/30 and .35-caliber carbines with open sights. These lightweight rifles were a pleasure to carry but when we shot deer at ranges of 200, 265, and 300 yards, we began thinking about more versatile rifles. Scoped rifles with flat trajectories are a real advantage at those ranges. At the more usual ranges of 50 to 100 yards, a deer is likely to be behind brush. It was once felt that heavy, slow-moving bullets could penetrate brush and still reach a deer. Actually, any good deer bullet is likely to kill a deer standing five feet behind a bush, but put the deer 20 feet behind the obstruction and even the best brush bullets may angle off too far.

Merle and I settled on .30/06 bolt actions. Left-handed Duane used a lever-action .243. We loaded the .30/06's with 150-grain, spire-point bullets on top of 51 grains of No. 4064 powder, which kicks them along at 2,850 feet per second. Duane stacked a 100-grain slug over 43V2 grains of No. 4831, and velocity approaches the 3,000 fps mark. Using these loads, our factory-made rifles all landed three shots within an inch on a target at 100 yards during practice.

Scope sights enable us to see more clearly where we are holding, especially on running shots or at long range. I started out with a 2.5X scope, but since I used my rifle on varments throughout the year, I switched to a 6X glass. This was fine for jack rabbits and crows but it had too narrow a field of view for running deer. Consequently, I ended up with a 4X scope.

We went into the 1964 season well equipped if not well versed on the ways of deer. In three years we had taken eight out of a possible nine deer. We had a reputation to uphold and the pressure was on. With two days left in the season we still needed two deer. Everything had gone wrong. We chased plenty of deer into other hunters and had them shot from under our noses. I missed a chance at a double on bucks by not following through with my swing so all I did was cut the brush behind their tails. The season was half over before Merle hit a two pointer with a 300-yard shot.

We moved into a new territory and found plenty of deer signs. A creek cut diagonally across the section with plenty of curves and lots of timber. Merle let Duane and me off on the up-creek side where the timber was widest, then took the pickup around to the other side. We waited for shooting light, then took to the brush.

The signs were right, the air was right, and the lingering dew enabled us to move quietly.

Duane and I separated. I waited at a point where the timber narrowed to only a few yards on either side of the creek. Before long, Duane came sneaking along; a dozen steps, then he would stop and watch.

Now across from each other, we headed at a brisk pace for the next big timber, when the sound of three shots rolled down from somewhere ahead. We needed JANUARY 1971 no consultation. Duane and I moved forward at a trot. Suddenly, Duane called out quietly, "Cacek, three deer across the cornfield. There's a buck."

With the creek between me and the deer it took a moment to spot them. The does led the way down a large, sparsely covered draw, across a fence, and into the picked cornfield. The buck dropped his head as he cleared a fence. The sun caught his antlers and I realized what a monster he was. Still 500 yards away, the critter looked all horns. Our luck had changed — those deer were coming straight for us. I moved to the edge of the timber and picked a clearing to shoot through. An hour seemed to pass, and I had nothing to do but wait around and get jittery. Duane opened up with his .243, but he had a tough crossing shot. He took out a leg, but neither of us knew it at the time. His shots turned the deer so they were quartering to my right. Still I waited. Every tree in the field seemed squarely between that buck and me. Finally a clearing-a split second. I threw the crosshairs ahead of his shoulder and fired. The buck piled into the cornstalks, falling out of sight. I reloaded and held my ground. Moments later another shot rang out and a relaxed voice called, "We got him."

"Whose wall does he go on?" I yelled back. We had shot simultaneously. The deer had fallen just after I fired, but with so much brush to shoot through, I couldn't claim a hit.

A closer look showed the size of our kill. He had the largest rack of any deer we had taken. There were five points on each side, and the beams were almost symmetrical.

Yes, our luck had changed. Another group of hunters had kicked out the deer. On the way to the check station, the question arose again —whose wall was the head to go on? After much consultation we decided that if there was a .30/06-caliber bullet in the deer's chest, he would be mine. If not, Duane's wall would have another decoration. Later, we found my bullet just under the skin behind the far shoulder. I had made a solid hit. It is very likely, though, that neither of us would have downed the buck without the help of the other, so we claimed him equally.

We had one more buck to get and only a day in which to do it. About mid-morning the next day, Duane clobbered a three pointer, so our reputation was safe for another year.

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission offers a citation for trophy deer. Scoring is done on the Boone and Crockett scale with typical white-tailed deer requiring 135 points to claim an award.

When Duane and I took our head in to be scored, the man with the tape took one look at it and said, "Fellows, it's going to be close." He said that again about a dozen times before he finished, but the final tally was 140 1/2 points.

The Blue Unit has recorded a lower success than many other areas of the state, yet Merle, Duane, and I, with Frank's help, filled 91.7 percent of our permits. How? It certainly was not due to our vast experience. The more we hunted deer, the more frustrated we became. Our only secret was hard work. The work began before the season when we scouted the territory, talked with landowners, and sharpened our shooting eyes. During the season we took advantage of every second and never passed up an area because it looked too difficult to hunt. Two of our deer were shot in the last hours of the last day of the season, so our motto was always —"Never Give Up." THE END

SHADOWS IN THE RIVER

(Continued from page 37)when a big paddlefish jumped clear of the water about 50 yards to the side of the boat. John headed for the spot where the fish had vanished. We made several passes over the area, but saw nothing more of the fish.

"I guess he's gone," John finally admitted. "In that case I'm going to shoot one of those buffalo," Jeff said, pointing to a large school 30 yards away. Raising his bow, he let fly as soon as we were close enough.

Both boys' bows are equipped with heavy-duty spincast reels. Seconds later Jeff was reeling in his fish.

Light was fading fast as we swung around and headed back upstream. Our conversation turned to paddlefish, also known as the spoonbill. In addition to bow fishing, both John and Jeff have taken paddlefish in the more conventional manner — snagging with large treble hooks and heavy sinkers.

A living member of an old group of fossil fish, this species' only near relative is found in the Yangtze River in China. Paddlefish are found in the Missouri, Mississippi, and Ohio river drainages. They reach a normal maximum weight of 90 pounds, although a 200-pound specimen has been recorded. Nebraska's snagging mark stands at 75 1/2 pounds. John's archery record paddlefish tipped the scales at 38 1/2 pounds.

Characterized by its long paddle-like snout and shark-like tail, the paddlefish is a worthy target for any bowman. Hunting several days each week during the summer, John and Jeff had accounted for nine paddlefish.

"They're nothing like carp or buffalo," John said. "We can go out anytime and get a dozen or more carp or buffalo, but paddlefish come a bit tougher." Jeff added, "We probably go out five or six times for every paddlefish we get."

Back at the dock, we agreed to meet again the next morning for another try.

The sun was just above the horizon when we slipped the boat off the sand and onto the river. This time John turned the pram into the current and headed upstream toward the dam. As we approached, the roar of cascading water filled the air. The choppy water and a brisk breeze buffetted the boat. Cormorants wheeled in the clear sky, diving occasionally for minnows in the fast-moving water.

About 150 yards below the dam John eased the boat up to a long, narrow, shale outcropping. Jeff threw the anchor onto the shore.

"It's against regulations to get out on the point, so we shoot from the boat," Jeff explained.

I was surprised to see the two brothers cut the fishing arrows from their bow-mounted reels. From the back of the boat they produced two white, plastic jugs. I had seen the jugs and had assumed they were just jug-fishing rigs. Now, however, I saw that each was equipped with line and another fishing arrow.

"When we first started bow fishing here, we realized that our regular rigs 56 just wouldn't work," Jeff recalled. "Whenever we shot a big fish he would take off downstream and take all the line off our reels before we could haul in the anchor and turn around to follow."

"That's when we thought of the jugs," John added. "This way, if we shoot a small fish we can just pull him in, and if we get a big one, we throw the jug out and follow it."

By this time the boys were ready and intently watching the deep, swift water. Minutes later the dark form of a large carp glided by, heading upstream.

"We've had our best luck at this spot," John reported. "We see a lot of paddlefish downstream, but you have to scare them up in the holes there, and shooting from a moving boat is pretty tough."

July had been John's month. A gar swimming near the point on July 2 fell victim to his arrow. The 16-pound, 6-ounce fish gave him his first state record, topping the old mark by 12 ounces.

"July 16 was the best bow fishing I had all summer," he said. "I got to the point just after sunrise, and within five minutes a paddlefish came by. I shot him, threw in the jug, and took off to run him down. It turned out to be a 20 pounder — the largest I had ever taken. I was pretty happy. It was still early, so I went back to try for another. And less than half an hour later, the big one appeared. I shot him, and before I got the boat turned around, he started heading the other way toward the dam.

"I was afraid he might make it to the buoyed-off area directly below the dam and I wouldn't be able to go in after him. I intercepted the jug just in time and led the fish downstream to calmer water where I finally landed him."

Jeff quipped that the fish was bigger than John. His comment wasn't too far from being true. While the fish's 38% pounds couldn't match John's weight, it measured 5 feet, 4 inches in length, only 4 inches shorter than John. The paddlefish topped the old state record by almost seven pounds.

A few carp and buffalo swam past the boat during the next hour, but paddlefish stayed away. Finally, Jeff suggested we run downriver to check the holes. There again, we spotted rough fish, but no paddlefish, and shortly after noon I reluctantly decided it was time to head for Lincoln.

"Sorry we didn't get one," John said, as I loaded my gear into the car. "But it's just as I said —paddlefish don't come easy."

"Paddlefish may not come easy, but you two don't give up easily either," I answered.

The Schuckman boys are not quitters, and, in view of their ages, there will likely be more changes in the bow-and-arrow records during the coming few years. THE END

THE TOUGH BREED

(Continued from page 53)were caretakers. After high school she met Earl, her husband-to-be, one Saturday night when he came to a dance in her home town. In 1947 she married Earl, and the couple moved to Barada in the extreme southeast corner of Nebraska. Earl, a mechanic for a few years, later became an oil-derrick rigger.

His accident happened in 1955. He was working up in a rig at Redfield, Iowa, when ice exploded from a pipe that had just been lowered into the ground, shooting up against his face. For years, he was in and out of the hospital, undergoing a series of 32 operations which, although they restored him to normal living, left him without a left eye.

After the accident, while her husband was bedridden much of the time, Kate decided she must carry on. The couple started a repair shop in Barada in 1956, a year after the accident. Earl still was not feeling up to par. And, because of his vision loss, he often bumped his head on hard corners in the shop and knocked himself unconscious while working. Kate, an equal partner in their new venture, had no previous training or experience, but trial and error quickly taught her to do the small jobs —fixing tires, changing points and plugs on cars, replacing worn brake shoes, and welding.

"People from Barada and the surrounding area brought us business, but money was still scarce," she remembered.

In 1958 the death of a friend led to a new source of income. The friend had no one to bury him, so Earl and Kate, out of the kindness of their hearts, dug a grave for him in a country-church cemetery.

"The next time there was a death in the surrounding community where there was no sexton, the undertaker at Falls City, who was in charge of the funeral, asked us to prepare the grave. Since there was no machinery, we used our spades and muscles to do the job. After that we were asked each time, and now dig in 12 different cemeteries. I don't feel there is anything unusual about it because I was raised in a cemetery home."

After Earl regained his health, he gradually assumed a bigger share of the workload in the shop, but with only half his normal vision, he often asked Kate to help him with delicate work. Their children, Nancy and Lyle, were in school during the day, so Kate spent as much time in the shop as in the house. And, she came to enjoy it.

The shop has been their livelihood ever since — repairing farm machinery, automobiles, power tools, electrical appliances, or anything mechanical, including welding.

But with all the duties this woman with the pioneer spirit has assumed, Kate still finds time for participation in community life. She is past president of the Richardson County Legion ladies' auxiliary, president of the American Legion Post 22 ladies' auxiliary at Shubert (six miles away), and president of the Barada Cemetery Association. During village elections she is registration clerk, taking the names of those who elect Barada's five-man council. Out of Barada's 45 residents, approximately 25 are eligible to vote and the turnout is usually 60 or 70 percent.

NEBRASKAland"The others don't care or simply don't want to vote," she theorized. She also participates in non-political work in state and county elections as clerk on the counting board.

Their children are almost grown up now. Nancy is 16, a student at Southeast Nebraska Consolidated High School at Stella, 11 miles away. Lyle, 20, works at the Cooper nuclear power plant under construction near Brownville, 20 miles away. Neither feels there is anything unusual about their mother working at what is usually a man's job. She is an accepted member of the community. If anyone ever made snide comments to Kate about her occupation, she does JANUARY 1971 not remember them. In fact, she laughs at the thought.

The Bridgmons are people with a strange way of life by most city standards. They represent a strain of hardy, modern-day pioneers, content with what they have. Their travels are few. Although they live only 95 miles from Lincoln, Kate has been there only once in her life. And their only long trip together was a vacation to Cheyenne, Wyoming in 1952, and that took plenty of planning. Then it was back to Barada.

At home, Kate does everything from repairing typewriters to overhauling engines. Her hardest job was replacing an automobile transmission without even a hoist to lift the heavy gearbox out of the car.

"We just had to jostle the transmission around with brute strength, and let me tell you, it was awkward," she said.

Breaks in shopwork come when Kate is called to a farm to repair a piece of unmovable machinery or a vehicle. She spends approximately 50 percent of her time in the shop, and the other half doing on-the-farm repairs. As jovial as she is talented, all members of the community like Kate, and she likes to chat with them about everyday affairs as she goes about her business, be it in the shop or on a farm.

This, then, is the life of Kate and Earl Bridgmon — not very far from urban centers, but as far removed from city life as if a barrier were built between the two. Yet, they personify a unique pioneer spirit that binds all Nebraskans together. THE END

THE MILL AT CHAMPION

(Continued from page 39)19th-century scenes of tranquillity. The Frenchman River tumbles down the dam and foams past and under the old mill. Trees line the stream and are reflected in a mirror-smooth pond above the dam.

Returning to the first floor, visitors will find an old platform scale, installed in 1893. Though time worn, the weights and counterbalances could still pass state accuracy inspection.

Display cases will chronicle the history of milling in Nebraska from early, water-powered structures to present, more modern, setups. Outside the building, another display will show different kinds of waterwheels and buhrstones used in mills.

The picturesque old mill, with its sleepy surroundings, was the background for Wayne Lee, local author of His Brother's Guns. The setting is immortalized in that volume for any who seek the flavor of another day.

Champion Mill is but one more example of Nebraska's rich heritage, preserved through the continuing efforts of the Game Commission. The quiet pleasures of a day filled with hardship continue to touch all who visit this historical site. THE END

TOMBSTONE

(Continued from page 19)estimates as to the monument's height. Cone and spire, Chimney Rock is approximately 300 feet high, the spire about 100 feet. Pioneer estimates of the spire alone ranged anywhere from 50 to 700 feet.

Another popular misconception of the pioneers was the fragility of the structure. Inter layed with Arickaree sandstone and volcanic ash, Chimney Rock is composed of Brule clay, a soft and easily weathered substance which is responsible for the dramatic contour of these bluffs. Heavily fissured, then as now, the pinnacle gave the impression of imminent collapse. Yet its frailty did not warrant the fears expressed by most of the early observers, who thought only a few more years were needed to wear the monument completely away. One writer spoke of its rapid decomposition and suggested that "...one would suppose that the first high wind would topple it down". And Father De Smet in 1840 estimated that in a few years this wonderful curiosity would "make only a little heap on the plain."