WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBBRASKAland

November 1970 50 cents A POINT SYSTEM FOR DUCKS Field Check for GAME RHYTHM METHOD FOR BASS WILDLIFE OF FORT NIOBRARA

For the Record... Pending Legislation

Government exists for one reason— to serve the people. And, specifically, the Game and Parks Commission is in business to safeguard, promote, and enhance the game, fish, parks, outdoor recreation, and tourism resources of the State of Nebraska. To do this job, and do it well, new legislation is sometimes necessary, and old laws must be changed. When the senators come to Lincoln in January, Commission representatives will be urging them to enact various proposals. Some deal with the quality of our environment and others are "housekeeping" moves. Of course, the interested members of the public should let their elected representatives know their feelings.

Among the legislation that the Game and Parks Commission will support in the next session are the following items: Support legislation controlling polluters. Our environment is at stake, and laws should be enacted that would prohibit industries from locating in a community until that locality has a sewage treatment plant that can handle the additional load.

Advocate the placing of all hawks and owls on the list of protected species, and at the same time provide for the protection of all rare and endangered species. National concern is being expressed over many once-common and now near-extinct birds and mammals. Nebraska, too, must share this concern.

Recommend the lowering of the minimum age for application for a big-game hunting permit to 14, with the requirement that the young nimrod hunt with the parent or guardian. Such a provision would allow youngsters to learn about the outdoors at an earlier age and help promote their desire to preserve the wilderness areas that make hunting possible.

Urge the licensing of the use of certain agricultural pesticides and aerial applicators. Here again, we are dealing with the need to protect our environment.

Recommend amending federal-aid matching legislation, so the general fund monies may be used to match resource management programs in addition to those financed by the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

Support legislation requiring an examination for taxidermists before issuing a permit. Federal law already requires this, but state law does not.

Advocate an increase in the license fee for antelope. At the present time, permit fees do not cover the costs involved in carrying on an antelope season, when such things as biologists' time, check stations, and game inventories are considered. We should also prevent the use of powered vehicles in the hunting of antelope.

Support putting all fur bearers back under the protection of season regulations.

And, last, but far from least, request an increased tourism budget sufficient to meet needs and allow Nebraska to at least compete in the marketplace of today for the travel dollar.

These, then, are a few of the items that this agency will propose to lawmakers to help us provide better service to the people of Nebraska. Your support would be welcome.

Willard R. Barbee Director, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission NOVEMBER 1970

Fashion, flair and fiber glass best describe the beautiful new sculptured Starlite Tub/Shower Enclosures. No grouting or tile is needed and relatively no maintenance necessary. Always easily wiped clean they continually look bright and new. Write today...

ANY ACTIVE outdoorsman who uses binoculars knows how L troublesome the instrument is, dangling from its usual neckstrap. Here is a simple harness to tame the cantankerous critter and allow you to ride at full gallop, chop wood, or get off a fast shot without interfer- ence, and yet keep the glasses ready for instant use while keeping them safely stowed.

You will need the following materials:

Two yards of strong dressmaker's elastic, one inch wide. Four snap fasteners, the kind used on leather coin purses. Some scraps of soft leather.

Cut one strip of elastic 20 inches long, another 10 inches long, and a third about 38 inches long. The actual length of this last strip can vary somewhat, depending on the chest size of the user.

Lay the 20-inch and the 38-inch strips parallel to each other. Connect their centers with the 10-inch length of elastic, sewing firmly. This forms a sort of oddly shaped "H" with the three pieces of elastic.

Remove the neck strap from the binoculars. Cut two tabs of scrap leather one inch wide and four inches long. Trim three inches of each tab so that it will pass through the carrying lugs of the binoculars.

Double this trimmed piece back on itself, and install a snap fastener to form the loop to pass through the lug. Now sew these tabs to opposite ends of the 20-inch strip of elastic. Cut two pieces of leather six inches long and an inch wide. Match them to the last six inches at both ends of the 38-inch elastic strip and sew them in place. Install two snap fasteners, equally spaced, to these 6-inch strips. The harness-making process is complete.

Attach the lug tabs to the binoculars, and slip the loop formed over your head. The binoculars should now rest on your chest, riding quite high, with the remainder of the harness hanging behind your back. Grab the free ends of the longer elastic, pull them around your chest, thread them over the center post of the binoculars and snap the ends together. To use the instrument, 1 simply grab it and raise it to your eyes. The elastic will stretch to permit this move, and its tension helps steady the viewing. Let go, and the glasses snap back to your chest, where they ride without any sway or bounce, out of the way until you need them again.

With minor alterations, this harness can be made to fit a 35mm camera, too. Once you have used it for either purpose you won't want to be without it. THE END

NEBRASKAIandHARNESS FOR FIELD GLASSES

This simple rig keeps binoculars snug, yet always ready for instant and steady viewing

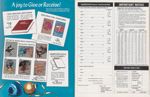

Been wondering what to get that special friend who has everything? This year, give the gift that lasts all year-a subscription to NEBRASKAIand Magazine. Fascinating, full-color photos highlight every 68-page issue, and there are thrilling stories for and about Nebraska and Nebraskans. And, when you order that gift, be sure to treat yourself to JMEBRASKAIand as well.

ONE YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TWO YEAR SUBSCRIPTION CALENDAR OF COLORAll new for 1971 hardly describes the changes in the NEBRASKAIand Calendar of Color. More pages tell you things you want to know, while the special plastic binding makes hanging easier. Larger pages make even more room for personal notes and appointments. Of course, attrac- tive, full-color photos still highlight each month, and a day-by-day list of statewide events is included throughout the year. Ideal for home or office, it's a great $1 gift.

ONLY $1 EACH PLUS SALES TAX

Speak Up

"Little did my father realize then that his participation contributed in any way to the total extinction of this splendid species, which at one time, we are told, dotted the skies in unbelievable numbers.

The part I played with the air rifle was great sport and was the beginning of my shooting activity and my fascination with firearms. I see, in retrospect, that I also have contributed somewhat to the decimation of the prairie chicken, which I now regret.

"The passing years have dimmed my enthusiasm for killing any wildlife. On the contrary, I really enjoy merely observ- ing all these beautiful wild creatures. "It is my hope that we humans shall do less killing and become more appreciative of our wild friends." —Donald T. Gregg, Escondido, California.

YOUNGSTER'S PLEDGE-"Enclosed is an original conservation pledge written by Robin Zinser, a 6th grade student. Robin attends the Lincoln Heights Elementary School in Scottsbluff. She wrote this pledge this year during a study of conservation in our state and nation. "I thought you might like to share it with NEBRASKAland readers."-Mrs.Jean Hall, Scottsbluff.

CONSERVATION PLEDGE by Robin Zinser Scottsbluff' I pledge to my country To conserve Water, for it brings me life; Forests, for they bring us homes; Soil, for it brings me food; Wildlife, for it brings my country beauty that will last forever. And I will conserve Liberty, for it brings everyone the freedom to love and conserve our Water, Forests, Soil, Wildlife, and other things, For ever and ever.SAVE OUR TREES —I wonder if everyone shudders, as I do, as they drive past the huge piles of tree trunks waiting to be burned — all that is left of a large shelterbelt. I think of the many others in this same area who are also bulldozing out their shelterbelts and I wonder how many more, all over Nebraska, are helping to bring Nebraska back into its former dust bowl state. "Research has shown that leaves of trees and shrubs absorb and filter out large amounts of soot, dust, and other particles floating in the air. Trees act as sound barriers, stop erosion, and help keep our rivers and streams clean." — Mrs. Ruth Warrick, Meadow Grove.

FAUNA BOOK-"Every month, NE- BRASKAland has one feature which excels. I refer to Notes on Nebraska Fauna. It is well written, well illustrated, and always educational. "Could this feature be extracted from past and future issues and published in book form? In this fashion, libraries, schools, sportsmen, and amateur naturalists would have a central reference point for the fauna of Nebraska. It would be an excellent educational tool, and one that would be uniquely Nebraskan, although of interest in a much wider market." —Eugene F. Tyson, Norfolk.

NEED MORE —"Please send more copies of NEBRASKAland to Oregon. One drug store in Hillsboro said they got only two magazines for August and they just didn't last. The grocery in Hillsboro, where I usually get your magzine each month, didn't get any. You have a beautiful magazine." —Mrs. O. A. Hoover, Hillsboro, Oregon.

The request for more magazines is being investigated by our circulation staff Editor.

CAUSTIC COMMENT-I have just completed an article in your heretofore good magazine. My congratulations to that great bunch of sportsmen?? from Wayne, (And Then There Were Six, August 1970).

"It must have been a great thrill to walk into a fenced area to do battle with a hog that had his teeth pulled.

"In all likelihood, they were the same big hunters who shot pheasants from windows of automobiles and made those very dangerous treks through farm groves and orchards killing very dangerous frying-sized chickens." —Marvin H. Duncan, Emerson.

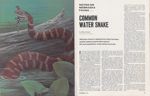

The boars had all of their teeth. Editor.BONE RATTLERS - "I was interested in the story, Once Bitten, Twice Shy (July 1970). We once lived on Bone Creek in Brown County. Across the creek was a den in which rattlers holed up in winter. I always carried a shovel and, more times than not, the next step would be on a rattler. I collected a large peanut-butter jar full of rattles and always took the head in and put it in the stove.

"We also raised turkeys, which were the best sirens we had. When we heard one of them sounding off, we knew there was a rattler. It seemed the easiest way to down one of the snakes was to play ball with him as he crawled along with his head five to seven inches above the ground.

"None of us were ever bitten, but we had to be on the alert all the time, especially when our grandchildren visited us." —Mrs. J. E. Brooks, Ord.

LOST: ONE TURKEY HUNTER

by Wayne Swanson as told to NEBRASKAIandTHE RED WINDMILL looked like a good stopping place and I had walked many miles before I reached it. I had been lost in the Pine Ridge since morning and it looked as if I might be there for quite a while.

The whole episode started on a frosty fall morning as Rev. Frederick Nolte of Emerald, and I headed out from our Fort Robinson lodge room on our way to the Chet Mansfield ranch. We were there to hunt turkey, and about half an hour before the season opened, we were sitting in the woods, listening to turkey talk all around us. Minutes after the season opened, a gobbler flew right into my shot pattern.

Soon, I was on my way back to the ranch, my turkey hunting over for another season. As I was about to return to Fort Rob, two Pine Ridge natives, Joe Waitman and Larry Kessler, both of Chadron, invited me to join them in a hike out on the ridge. I agreed.

I had not even picked up my shotgun when my partners in this unex- pected adventure reminded me that NOVEMBER 1970 grouse season was still open. So I grabbed my shotgun and six shells.

As we trekked along the ridge, we spread out. Soon the others were out of sight. As previously arranged, I called them twice. Each time they barked back an answer. The third time, though, my call met only silence. Turning abruptly, I strode back to my starting point. But the Pine Ridge had tricked me. I was not where I had started. It was a gloomy day with a heavy cloud cover in the sky.

I knew the Mansfield ranch was north and hoped that, even if I missed it, I would walk into the open around the White River where I could find my way. To keep from circling, I chose four landmarks at a time, lined them up straight ahead and behind me, and started out.

Even if I were mistaken on my directions I would not be lost for long. I could walk out. I began walking the way I thought was north.

I set out purposefully and continued to walk most of the day. About noon, I came upon the red windmill. There was another weather-worn windmill in a draw nearby and I decided to stop there to rest. I piled some dry grass and twigs around the weathered beams and dismantled two of my six shells. Adding the powder to the dry materials, I loaded my shotgun with just the primers and fired into the powder, hoping a spark would ignite my fire lay. My attempt failed, though, and I set out again with no heat or signal fire.

By this time, I guessed that I was going south instead of north. But I figured to reach the edge of the Pine Ridge by continuing straight ahead. From there, I could follow a fence line to civilization, for ranches surround the butte country. It was getting late when I reached a haystack where I decided to spend the night. I needed shelter from the 19-degree temperature, so I dug into the stack, looking for a dry bale. I had to crawl practically to the middle of the stack to find what I needed, for recent snow had left the outside layers soggy.

When I found the dry bales, I tore one apart and worked it into a natural, unpacked condition with my fingers. I knew that with only a camouflage jacket over my sweatshirt, the night-time temperature would be, at best, uncomfortable. I needed shelter and I used the loosened hay as a blanket.

I had worked my way down into the stack, ready for sleep, when I heard a search plane flying a pattern across the ridge from me. I crawled out again and loaded my shotgun with two more shells. After about half an hour the plane flew directly over me and I fired twice, hoping the pilot would see the flash coming from my high meadow position. I had no luck, though, and after watching the plane disappear, I lay down to perfect silence again. I dropped off to sleep with only the nagging growl of my stomach to keep me company. I slept comfortably and warmly, and awoke after daylight to the sound of mooing cattle. I knew I was near a ranch.

I had started walking again when I heard the plane, so I circled back. This time the pilot spotted me before heading back to civilization.

A line of cars, like a funeral procession, soon came out to meet me. I climbed in with Conservation Officer Marvin Bussinger, and gulped down a candy bar, my first food since the previous morning's breakfast. I had been lost a total of 28 hours and, ironically, when I was found, I was within a mile of a ranch. I had almost walked out of the Pine Ridge. Another hour would have found me on open ground. THE END

15

SKY'S THE LIMIT

by W. Rex Amack Though fraught with danger, Omahan's vocation has one definite asset No one ever climbs up to check his workFEAR AND GERRY VAN SANT are strangers when it comes to heights. The "sky's the limit" for the Omaha steeplejack who has some 20 years of sky-scaling experience behind him. His paint and brush, meager climbing equipment, and steel nerves have taken him across the United States on contracts ranging from skinny poles to giant grain elevators, to the peak of a flagpole towering over New York's Empire State Building.

Professional steeplejacking joined up with Van Sant at the end of a four-year hitch with the Navy. Original post-Navy plans called for Gerry to become a fire fighter. However, when those plans were abanoned, he decided to become a painter and specialize in steeplejacking, a decision which has resulted in considerable financial success and personal gratification.

NEBRASKAland found Gerry Van Sant after a somewhat complex steeplejack search. It seems that everyone talks about climbing poles and steeples, but like the weather, few folks actually partake in the doing. NEBRASKAland has left the ground on many occasions ranging from skydiving to gliding planes, but this assignment called for a turning of the tables from sport to livelihood.

A leisurely summery breeze swept away the heat of a hot July day when Lou Ell, NEBRASKAland's chief photographer, and I met Gerry at his Omaha headquarters and he agreed to give us a first-hand look at steeplejacking. Gerry's business has grown into a full-fledged general construction company in the last few years, and management work has demanded the majority of his time, cutting out much of his steeplejacking. But, according to Gerry, he's a long way from retiring from steeplejacking, and maintains several accounts in Omaha.

"There are a lot of good things about steeplejacking," Gerry began as we loaded up and headed for the day's job. "One thing is that I've never had anyone climb up and check my work, and consequently no complaints," he quipped.

Gerry informed us that we were headed for a private residence in west Omaha where he would tackle a flagpole. He was going to install a rope and paint the pole. We had to stop at a paint store on the way.

"Wait," I said. "What about your equipment? Don't we have to stop somewhere and get that?"

"No, I have it," Gerry replied, as he held up a crumpled coverall-type outfit and two thin and short peculiar-looking ropes. Lou and I both sighed in wondering tones.

After picking up the paint we continued on our journey. The conversation was somewhat one-tracked as Lou and I fired questions at a machine-gun rate. If curiosity really did kill the cat I knew for sure NEBRASKAland would soon be two workers short.

Gerry fielded the questions as best he could, usually just getting started on one when another hit.

As we rode, he pointed out countless super-high structures that he had painted or repaired at one time or another. Watertowers, smokestacks, flagpoles, church steeples, grain elevators — if it was out of reach, Gerry seemed to have been there.

He told us of climbing experience upon climbing experience. Recalling a particularly dangerous smokestack he painted once, he remembered that it was some 350 feet high. He had been hired to paint the name of the business that the smokestack was attached to. So, paint he did. The job was a real tickler, so he told it, and when he finally (Continued on page 59)

MODERN-DAY RUSTLING

Part of the Old West lives on as midnight cowboys delve into ranchers9 cattle coffers

GONE ARE THE DAYS of fenceless prairie, when sleek cattle grew fat and expensive on limitless miles of virgin grass. Here to stay, however, is one of the most romantic, if not the healthiest of professions — cattle rustling. Time was when any cowpoke with an eye for a fat heifer and a burning desire for a fast buck could walk onto just about anyone's range and make off with his prize.

Or, if he were really sneaky, he might snap a blanket before the eyes of a cow on a trail drive and wait for the resulting stampede. Then, as drovers busied themselves trying to round up the scattered critters, the rustler simply cut out the stock he wanted. By the time anyone realized the beeves were gone, the thief was long gone and considerably richer. At least he was richer if he didn't try to peddle his wares in an area where the stock was known. But at the most, contrary to popular belief, his nefarious deed usually netted him only three or four years in the pen. Few rustlers were hanged in the state. Even on a "lawless" frontier, jurisprudence took precedence over lynching.

With the passing of the open prairie, a good share of the West's rustling problems subsided. Barbed wire brought a somber note to the world of cattle crime. And police practices were improving faster than most crooks could devise ways to elude arrest. Cattlemen, too, were becoming more and more conscious of the loss they might take at the hands of a scheming cattle thief. So, a goodly number of this shady breed turned their greed to other pursuits — most of them illegal. But there are die-hards in every business, and pressures of the law and public opinion served only to increase the thrill and the lucrativeness of heisting someone else's livestock. Without change, nothing (Continued on page 54)

CHECKPOINT CHARLIE

A different breed of hunters stalks the field each year. Dedicated to gaining knowledge of different species, their actions mean better game management and hunting promises

EACH YEAR, come hunting season, thousands of outdoorsmen flock to the hills and fields of NEBRASKAland in search of game. Their goals are to reap a harvest of the state's bountiful wildlife crop, thus satisfying a drive common to all sportsmen.

Yet there is also another kind of hunter in the field each year. He is the game biologist of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. And his goal is to accumulate information from various sources and on a variety of species. So, he sets up and mans the check stations so familiar to successful hunters.

While check stations are most familiar to big game hunters, those after deer, antelope, and turkey, they also exist for the pheasant, quail, and grouse gunning sets. The information collected has helped in developing sound management programs for the species involved. Biologists report that hunter co-operation throughout the past years has been good and most hunters do not object to this temporary inconvenience as long as they are providing necessary information.

What happens at a check station is pretty much dependent upon what species the hunters bring in. Yet there are specific methods common to all. The first check stations to be set up each year deal with grouse. When the hunter arrives at a check point with his bag, biologists examine the flight feathers and feather patterns on head and tail to find the age, sex, and proportion of prairie chickens and sharptails taken. They also discern the total number of birds taken, hours hunted, and locality where the birds were bagged. From this, hunter success is calculated and reproduction success from the different areas can be studied. While all figures are approximations, they are close enough for the scientists to make intelligent guesses about the status of the species.

Those stations dealing with pheasants are a bit more detailed. Biologists examine the bursa, a shallow pocket on the back part of the gut near the anal opening. By measuring the depth of the bursa they can determine the bird's age. The bursa is longer in young birds, but as they mature, the pocket recedes and finally disappears. Though it may have had some biological purpose in the past, the depression today gets its best workout as a calendar of age for personnel manning check stations. Biologists report that this method is almost 100 percent accurate. Other aging techniques used in the past proved less reliable.

One of the other methods used to determine pheasant age was to hold the entire bird up by the lower mandible, one of the mouthparts. If the lower half of the bill broke, the bird was judged a young one. If it did not, the rooster had been around a while. Differences in each bird's makeup could throw the whole process off, however. Also the amount of time that had elapsed between when the bird was shot and when it was checked could make a difference as to whether or not the bill would bend.

An old standard for several years was the age gauge. This unimpressive-looking plastic ring was hollowed out in the center to a given size. It was placed over the lower portion of the leg and moved downward. If it passed over the spur, the pheasant was considered a young one. If it did not, the spur was more developed, indicating an older rooster. This method is reliable early in the season, but later on, spur development of young birds will indicate that they are adults according to the gauge. However, spur and feather development are important characteristics which are useful in determining age ratios.

While the biologists have the last say and are really the only ones who can give meaning to many of NEBRASKAland

When a quail is brought in, personnel determine the bird's sex. Yet, the hunter can do it in the field— just for his own information — if he knows what to look for. Male birds have a white patch on their throats and white eyelines. If these signs are buff-colored, the quail is a female. Aging the birds is a bit more tricky, however. Biologists usually end up collecting wings for later study. Then, they go by coloration and feather development. If the primary wing coverts are uniformly dark, the bird is older. Young birds display white tips on these feathers. Growth of the flight feathers on the young birds tells the story as to when hatching took place. By measuring the length of the feathers, which are moulted and replaced at a predictable rate, it is possible to back-date for determining the peak of hatch.

All of these check stations are strictly voluntary. Hunters are not required to stop. Yet hunter response and co-operation has been quite good.

On the other hand, big game —deer, antelope, and wild turkey— check stations are mandatory. Any hunter with a kill must bring his game to a check station to have it examined. Game biologists are assigned to those stations which are expected to have the greatest number of animals. The more heavily used stations are manned by game biologists throughout the season. However, because of the number of stations involved, the ones with fewer animals passing through are staffed with temporary personnel. These people primarily record species and sex information. Larger sta- tions with permanent help delve into sex, age, weight, species, and other factors. Age information is derived from dental factors, with the amount of wear on the teeth providing information of the age structure of the herd. While antler and horn growth is helpful, it is the teeth that really give the true information.

Game biologists point out that the mandatory check stations are largely located with hunter convenience in mind. For instance, last year there were 82 stations across the state to record hunter success during the firearm deer season. There were more than 90 units for archery deer kills and 30 for antelope archers, while the antelope rifle stations numbered around 30. Turkey stations are operated during both spring and fall seasons. During the fall hunt, 8 stations are operated and about 18 stations are manned during the spring season.

Voluntary check stations were less numerous last year with only 14 stations devoted to pheasant. Quail accounted for one and grouse were checked at nine. The main consideration in the location of voluntary stations is the selection of a site where a large segment of the hunting public can be contacted and where there is a safe pull-off place for hunters to stop.

What the whole check-point system boils down to is good management. To have a sound management program, biologists must have information on game in the field. The check station gives them a good idea of what is going on "out there". A spinoff from the primary mission is the biologists' contact with the hunter. During that contact, they have a chance to ask the questions that can lead to better game in the future. They can also field questions from outdoorsmen and answer any gripes that hunters may have.

So, in this year's season, take the opportunity to stop at the check station, be it mandatory or voluntary. There is a good chance that with your co-operation, the future of Nebraska's game populations can be improved even more. And you might get the answer to that question that has been constantly nagging you since last season. THE END

NOVEMBER 1970 21

FORT NIOBRARA

With a present as colorful as its past, this frontier post is wildlife refuge that offers naturae at her very best

22 NEBRASKAIand NOVEMBER 1970 23

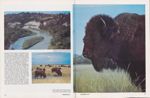

RUNNING CLEAR AND COLD, the stream meanders over the sandy soil on its short trip to the Niobrara River in north-central Nebraska. From its source as a spring it is just a few hundred yards to where the water ripples down the face of a pock-marked slab of hard clay.

Just as in 1879, when the first "horse soldiers" arrived to establish Fort Niobrara, the spring water continues today. Once the domain of bountiful herds of buffalo and elk, the hills that became the military reservation of Fort Niobrara sprawl on both sides of the scenic Niobrara River. Wooded river breaks and gently rolling pastures intersperse the terrain. The tiny stream gurgles down the cupped "rock" to form Fort Falls, and the trees, bushes, and grasses growing on the steep banks create a cool retreat in con- trast to the wide southern expanses and rugged eastern bluffs.

Life was tedious for troopers assigned to the post in early days. For men unaccustomed to the plains, the winters were harsh and the summers withering. Maneuvers and weather extremes were the only respite from the boredom of soldierly routine, however, since no battles or skirmishes materialized during the 27-year history of the fort. Its purpose was to serve as a deterrent to Sioux Indian troubles in the area, and possibly it did serve that purpose well.

Severe weather and the isolation of the fort made assignment there a memorable

period for the troopers. In contrast to the attitude of the soldiers, today's visitors are enthralled with Fort Niobrara, partly because of the wildlife. Fairly stable levels of 220 bison, 230 longhorn steers, and 50 elk are maintained. Also, a number of deer inhabit the region, but because of their ability to jump the seven-foot fence, their numbers are difficult to tabulate.

After the 27-year military assignment ended, the post was virtually abandoned in 1906, and used only as a cavalry remount station for several years. Then, in 1912, dismantling began. But, just as the last buildings and bricks were being removed, a portion of the land was designated as a federal range to accommodate a gift of several head of bison, elk, and deer. This initial donation was the start of something, for later the "refuge" was expanded to its present 19,122 acres.

Even though the last remnants of the once-bountiful herds of buffalo and elk had long since vanished, their cousins were again grazing the same grasses. The first elk donated to the government

were subsequently supplemented with animals from prime herds elsewhere, but all buffalo are direct descendants of the original six animals. Now, only the best specimens are retained. Excess stock is auctioned off each year to growing numbers of bidders. Many of these animals start or add to private herds, while others f;o to zoos or into stews. For some, at least, ife is quite idyllic.

In a small museum located at the headquarters complex, samples of the longstemmed grasses that grow profusely in the area adorn the walls. Maps, old photographs, letters, and other paraphernalia point out interesting periods in the history of Fort Niobrara. In other rooms are curios of ages past in the form of skeletal remains of prehistoric creatures, along with mounted birds and animals common to the region today.

A canoe access point allows easy launching for persons who want to see the imposing cliffs and canyons from the bottom up. For several miles, the Niobrara River wends its way through the refuge, and the scenery is magnificent whether viewed from above or below. During the summer months, the buffalo are in the pasture overlooking the river, and may occasionally be seen peering down into the canyon. Young-of-the-year are grazing with the herd then, and they scuffle amongst themselves and frolic amidst the elders who put up with their frivolity with a seemingly stoic patience developed over many years. Life expectancy of these one-ton creatures is about 30 years when they have the absolute protection which the refuge provides.

Entrance to Fort Niobrara is normally via a bridge across the river about three miles northeast of Valentine, but the bridge washed out two years ago and has not yet been replaced. Presently, another entrance, about 22 miles farther away from the turnoff, is used. A new bridge is expected to be completed within the next year.

Although access to the refuge is somewhat difficult in the interim, the rewards of a visit are manyfold. There is a scenic splendor, a wildlife-viewing opportunity unique in this area, and an aura of historic significance, which makes it easy to visualize days of long ago. Here is a territory, not only unchanged from centuries past, but restocked with beasts that once were the sole occupants. THE END

RHYTHM METHOD FOR BASS

Grand Island angler spent 15 years perfecting his system. How time pays off in bid gishing dividends

TAKE ONE HEAVILY fished lake and put a dozen, or a hundred, average fishermen on it, and they won't have any luck. An occasional small bluegill may rise to the bait, but the lunkers will stay right where they are.

There are still plenty of big fish in there, but they can easily resist all efforts of the so-called "average" angler. It takes a mighty skilled fisherman, or one with a secret, to get unwilling fish to bite.

Now, there is a method that is almost guaranteed to catch bass from even a heavily or over-fished lake. Norbert Banners, a Grand Island man who has turned almost professional angler, has evolved a method of catching bass even on the hottest, clearest day in midsummer when bass are just not to be had. Last year, for example, he landed an astounding 750 bigmouths.

Bert, as his friends call him, has been fishing for more than 55 years, and the last 15 have been devoted to perfecting his rhythm system for catching large-mouth bass. There are many fishermen who have already been introduced to his method. These people are sold on it and are always ready with testimonials to its effectiveness. Such things as, "Bert is the best fisherman in the state," and "I couldn't catch a fish 32 until Bert showed me how," are replies you get when asking these anglers what they think.

Mormon Island Lake at the Grand Island Interchange of Interstate 80 is a heavily fished area. Commonly called "Steen Lake" in honor of former Game Commission Director M. O. Steen, the lake often has more than 100 people fishing it daily during the summer. Despite this pressure, Bert can stroll out there and catch bass when no one else can. Just since the lake re-opened in April, after extensive developments were completed, he caught 275 bass in two months. Now that is fishing. Of course he put most of them back, but he probably catches more bass from that lake than all other fishermen combined. That speaks highly of his system.

"I prefer to fish from the bank," he explains. This is remarkable because most fishermen strolling the banks wish they had a boat to get out where they think the fish are. The fish are not out in the middle all the time, though, for Bert has his best luck near shore, where bass move in to feed.

In the spring, during heavy bass-feeding activity, Bert can catch his limit of bass in minutes, even in lakes that are not chock full of largemouths. Most NEBRASKAIand

So, after hearing about his prowess with fishing tackle, NEBRASKAIand Magazine sought him out to study his methods and success.

Possibly the timing was unfortunate, but not intentionally. So August 25 was selected, and some of the Interstate lakes near the Minden Interchange would be the testing ground.

A worse day to catch bass would have been hard to pick. And, we didn't go at the best time of day. Normally, bass can best be taken in very early morning, evening, or at night. When asked if we should meet him in the pre-dawn dark, Bert replied, "I like to fish when it's light," thus foregoing any advantage.

Consequently, it was after 9 a.m. when we arrived at lakeside, dubious but ready. My tackle box was abandoned in the car, since all that Bert carries are his plastic bag jammed with various-colored plastic NOVEMBER 1970 worms, a small box of spare hooks, and his fancy rod and spinning reel. I rigged exactly like him —in fact he did it.

Off came my swivel and snap. He simply tied on a gold No. 6 hook, which is about three-quarters of an inch long. With this secured, a large black plastic worm, about eight inches long, was hooked through the clitellum, the large bulge or collar. A BB-size split shot was clamped on the line a few inches ahead of the lure, and we were ready to go.

Bert's bass formula starts with the cast, as he demonstrated. As his worm hit the water, he quickly slammed the bale shut and skittered the plastic wiggler across the top of the water for a short distance, perhaps a foot or two. This was to draw the fish's attention to the fact that something edible was in its domain.

After the water-skimming maneuver, the worm was allowed to sink a ways. This depends on water depth, so different depths are tried. Now for the rhythm, leaving out the jokes about birth control. It involves a steady, rhythmic twitching of the rod tip, then every four twitches, but without breaking the rhythm, giving the reel (Continued on page 51)

33

HUNTERS GET THE POINT

SEVERAL THINGS were unusual about this duck hunt. For one thing we couldn't shoot until sunrise instead of the normal half hour before. This was because we were right in the middle of the High Plains Experimental Point System Season.

The special season of 1969-70 was an experiment to direct shooting pressure to one species of duck and away from others. In this case our targets were mallard drakes, and all other ducks, as well as mallard hens, were taboo.

Depending on our ability to identify birds before we shot, we could take as many as four hefty mallard drakes, such as the ones we were watching as we waited for shooting time.

Only that part of the state west of U.S. Highway 83 was open, and bag limit was based on points, with a bag limit being filled when the total reached or exceeded 40 points. Mallard drakes counted 10 points toward the total. Hen mallards and all other ducks were 40. If one of these was killed, the shooter was done for the day.

I have lived in Bayard all my life, and was hunting with my teenage son, Brad, and his friend, Jim Wefso of Rushville.

Another unusual thing—a 40-mile-an-hour wind howled around us as we huddled, shivered, and watched the cloud-darkened sky. We were southeast of Bayard on a three-channeled part of a mile-long stretch of the North Platte River that I lease. We had waded the south channel in the early morning light and decided against setting up in our island pit-blind in the main channel. We built it mainly for ambushing an occasional flock of geese that moved along the river. We had some good mallard shooting there, but this time we headed downriver about a quarter of a mile to where the channel split around a willow-covered island.

Here we hunkered down behind a small Russian olive tree and tried to get out of the wind. I shivered as I huddled deeper into my coat and wondered if my other teenage son, Scott, had not been wise by electing to pass up this particular hunt.

I tried to keep warm by remembering how, only a week ago, Brad, Scott, and I, and Jim Krantz, one of the fellows from the bank, had crouched here and clobbered 16 beautiful greenheads out of the plentiful flights that cruised back and forth along the river.

A glance at my watch told me I could now put my memories into action and try for a repeat performance of that exciting day. Action was not long in coming. A dozen birds were beating their way laboriously into the wind, making slow progress as they came upriver towards us. They dropped lower as they skirted the willow-covered island, then swung over to our side of the channel and headed right for us.

"Now," I yelled, as I lurched up and hurled two three-inch magnum loads of No. 5 shot into the wind. The wind muffled the blasts of my 12-gauge auto-loader, making them sound just as ineffective as they were.

"Darn wind," I thought, as Jim Wefso shot, and then Brad let go. One of the flaring ducks cartwheeled in the wind and plummeted into the water. Blown downstream, it was already disappearing around a bend when Brad hitched up his breast waders and

charged stiff-legged along the bank yelling, 'Til get him!"

"I wish I had my old dog Herman, a Chesaeake retriever, again this year," I said to Jim. "He would come in handy today."

"Yeah," chanted Jim through chattering teeth.

We had always had a good retriever and really missed the old Chesapeake when it came to getting fallen ducks out of fast water. He had died of old age the year before and we had not found a replacement.

Brad was out of sight around a bend in the channel and was gone for a long time. Expecting him to come back grinning with a big greenhead, we were surprised when he trudged up with his head lowered carrying a mallard hen and looking mighty disappointed. He was also mighty wet.

"What happened to you?" laughed Jim.

"Aw, I got into the water too soon when I caught up to this darn duck, and had to run a little to get him. I tripped over a root or something and went right under. Looks like I'm through shooting for the day, too! I could see this one was a hen in the air as soon as it started to fall, but then it was too late!"

While Jim chided him, Brad braced himself against the chilly wind, pulled off his waders, and dumped the water out of them. Then he wrung out his socks and pulled the soggy waders back on over his wet clothes.

The ducks continued to move upriver in the gusty wind, dropping low to fly over the willow island and then heading for us as we crouched on the bank of the channel. The next ones to come within range were three big mallard drakes, and they were almost close enough for a shot by the time I could be sure about their sex against the gray-black sky.

Brad prodded Jim with, "Shoot the closest one!"

The slim 14-year-old from Rushville let loose with his 12-gauge over-and-under double, but to no avail.

"I'd better live up to my rank as senior gunner in this gang," I thought as I swung on one of the escaping greenheads. This time I connected and he slammed into the bank so hard that the skin over his breast split. We could see a crop chock full of corn when I brought him over to the boys.

By this time Brad was turning blue from his dunking and exposure to the frigid wind. He jumped at my suggestion to head upriver to the little trailer wre had near the bank, and to a nice warm propane heater.

Brad, who is 16 and a sophomore in high school, is huskily built and pretty tough. He plays football on the school team and lettered on the wrestling squad, but no one could tough it out very long, soaking wet in that chill north wind.

As Brad disappeared through the trees on the bank, I said to Jim, "Let's move over to the end of that island and see if we can get you some good close shots."

"O.K.," he agreed. "I'm having trouble hitting them in this gusting wind." Jim's dad, Fritz Wefso, is a pharmacist in Rushville, and had Jim pretty well broken in on pheasants, but the boy had not had much experi- ence with ducks. My boys had met Jim in Lincoln at Joe Cipriano's basketball school, and the three had become good friends. Jim was staying with us in his days off from school just before Christmas. Scott and Brad had been Jim's guests for a pheasant hunt in the Rushville area earlier in the year, and this duck hunt was sort of a trade. I really wanted Jim to score on a duck or two.

We got into the water and started for the island. It was rough going with the current of the waist-high water tugging at us and the wind trying to knock us over. Finally we hunkered down in knee-deep water at the edge of the island.

"These willows will keep the ducks from seeing us until they're just about overhead," I said. "By then it will be too late."

The island was about 100 yards long, 20 yards wide, and the willows grew right to the edge. We didn't have long to wait. A good bunch of ducks with plenty of drakes appeared above the willows about 30 yards away.

"O.K., Jim," I whispered.

The boy straightened and fired two loads of No. 4's from his double, but still no hit. I'll have to admit it was tricky shooting, because the ducks had done the same thing as those before them. They had come up into the wind high, almost stationary. Flapping hard until they were past the island, they swooped down and over to the south bank and on up the river.

The ducks were really moving now. We had been out about two hours, and flock after flock filtered up the various channels or zoomed back downriver high and hard.

Six drakes appeared above the willows just out of range and seemed to hang motionless as they beat into the wind. Seeming not to see us, they finally got by the island and started down. I caught one squarely on my first shot, and he splashed down just in front of us. I swung on another as he flared up and back with the wind, and caught him overhead with my No. 5's. He turned round and round as the wind whipped him back along the island, crashed through the willows, and hit the ground with a thump.

Jim had not shot and shook his head as he pulled the first of my double from the water. It was a tough way to break into duck shooting. After retrieving the other greenhead from the willows, we again crouched against the bank, standing in the water to get lower.

The birds were flying higher now, and it was some time before another bunch came within range. Jim fired futilely. He didn't really have his heart in it.

"How about heading up to the trailer to get warmed up, and to see how Brad is doing?" I suggested.

"I'm for that," smiled Jim.

We gathered up my three drakes and were soon shucking (Continued on page 51)

INDIAN WARS CORRESPONDENT

Unpublished manuscript describes dangers Chadron editor faced in last battle between Cavalry and Sioux near Pineridge

THE TERM "war correspondent" is generally reserved, in the more popular sense, for those gentlemen of the Fourth Estate who were part of major conflicts such as the Crimean War, the American Civil War, the Spanish-American War, or the First and Second World Wars. But in a literal sense, the term applies to any journalist assigned to cover any conflict between nations. It means the writers who covered the American Indian Wars were, in the literal sense, a group of correspondents of another breed. Although less sophisticated than their 20th-century counterparts, the Indian Wars correspondents made up for it by being characters sometimes as colorful as their subjects.

One of these characters, and others he wrote about in an unpublished 298-page manuscript entitled In The West That Was, was the late Charles W. Allen. His manuscript is an impressive account of experiences in the early West, the most outstanding being his eye- witness account of the Battle at Wounded Knee. It includes his own movements during the actual fight- ing as he ran back and forth trying to avoid being shot, still wanting to see the action in order to be able to write his story. He was editor of the Chadron Democrat at the time, and a freelance journalist working for the New York Herald.

During his life, Allen adopted numerous vocations, then opted out of them again. He celebrated his 20th birthday herding cattle at Point of Rocks near Chugwater, Wyoming, on the Cheyenne-Fort Laramie trail. For a decade he worked out of Fort Laramie with Cuney and Ecoffy Freighting, one of the major companies in the West, rising from utility man to head mule skinner. He subsequently formed his own freighting company, then sold it and moved to Pine Ridge, South Dakota, from where he hauled goods to the Rosebud Reservation, and on to the Missouri River. He worked on the log buildings at Pine Ridge and established a lime kiln there which provided a local supply for plastering. Later, he worked in a government warehouse at Valentine, Nebraska. Still later, he purchased a blacksmith shop which blossomed into a booming business in that northern Nebraska town. He married Emma Hawkins, a quarter-breed Sioux, in the 1870's.

In his otherwise inconspicuous family tree, there was one branch on which he always looked with pride. He remembered the vivid tales he had been told as a boy about his grandmother, whose maiden name was Rose Butterfield. Her distinction lay in the fact that she, being a cousin of Captain Oliver H. Perry, had stood on the shore of Lake Erie with Allen's father in her arms, listening to the roar of the guns in the battle which culminated in victory for Captain Perry in the War of 1812.

During the mid-1880's Allen turned to a new profession, the one which led him to witness the Battle at Wounded Knee near Pine Ridge on December 29,1890, and the career which earned him a niche in Western history. His personality lives on in a little gray file carton on the third floor of the State Historical Society's building in Lincoln, waiting to pop up like a jack-in-the-box whenever the carton is opened.

In 1885, Allen, having moved to Chadron from Valentine, formed the Democrat Publishing Company and became editor of the Chadron Democrat, later named the Chadron Citizen. As a fledgling journalist at the age of 34, he associated with others in the business and found himself covering the events leading up to the Battle at Wounded Knee —and the conflict itself — on a freelance basis for the New York Herald and for his own paper. His presence in the area during the battle led him to write the book In The West That Was in 1938, which he tried unsuccessfully to sell to three different publishing companies.

From the dog-eared manuscript of this unpublished book emerges an account of late 19th-century journalism about what is (Continued on page 48)

38 NEBRASKAland

Rainbows over Nebraska

More than century of use, development has put irrigation in driver's seat of farming. By-product is watery beauty across the state's verdant heartland

THERE ARE RAINBOWS in rural Nebraska each summer that come and go like dreams from night to day. They are the romantic by-product of a dream that came to stay —irrigation. When the weather grows warm and the clouds disappear, farmers hook up their irrigation pipes and sprinkler systems to provide life-giving water for their infant food crops. Acres upon acres of grain bask in cooling showers, provided artificially by those who wish to increase the state's productivity and, while doing so, cause the colorful and refreshing mists to drift across the land.

When one thinks of irrigation in Nebraska, one thinks of farms. During the summer one can drive along country roads and see long metal pipes and neatly dug ditches alongside the fields. These pipes and ditches are part of a vast network across the state, used to provide the land with moisture. It is a network with a history dating back to 1866, when the first irrigation ditch was dug by John Burke near North Platte. From that time on, gravity irrigation developed spasmodically until the 1930's, when irrigation began to take a much more important place in the minds of those concerned.

Another, more colorful part of irrigation's history is the role of the windmills which were used to pump groundwater to the surface, primarily for range cattle and for watering small two to five-acre plots on the dry prairie farmsteads.

A windmill, at that time, was considered to be a modern method of pumping water, compared with hand pumping. In a book entitled Wells and Windmills in Nebraska, published in 1899 by Washington's Department of the Interior, Erwin Hinckley Barbour wrote that throughout his late 19th-century research travels, he found no one who was critical of windmills.

"What a contrast may be provided by two farms —one with cattle crowding around the well, waiting for some thoughtless farmhand to pump them their scant allowance of water, the other where the cattle are grazing and the tanks and troughs are full and running over to such an extent that the hogs have their wallows in which to resort in the heat of day."

That's how it was in the 1890's. The windmill constantly pumped water which was used for cattle, small plots, and more often than not, for flowerbeds around the homesteads.

Before farmers developed extensive pump irrigation systems on their land, a large amount of investigation was done to determine the abundance of underground water in the state's areas. This began in 1930, and is continuing today. This summer, the test drilling is taking place in the rolling Sand Hills under supervision of the University of Nebraska's Conservation Survey Division and the United States Geological Survey Division. It is this continuous search which has made it possible for the experts to gaze into their

42

crystal balls and know that, by the year 2000, approximately 6,000,000 acres in Nebraska will be under irrigation, a vast area when compared with earlier acreages. Reliable statistics for early times are not available, but it is estimated that in 1900 there were only 1,200 acres under irrigation. This increased to 1,000,000 in 1950, and the present acreage is approximately 4,000,000.

Until the drought of the 1930's, ground water remained a vast, unused resource in Nebraska. Today there are ever-increasing numbers of wells being drilled, and the acreage under irrigation from surface reservoirs is also increasing, although not as rapidly. Out of the 4,000,000 acres under irrigation this year roughly 1,000,000 are serviced by surface water! The other 3,000,000 are serviced by wells which tap the underground reservoirs.

Irrigation is different in the Midwest than in places like California or Arizona, where artificially provided water is almost the sole source of moisture for crops, and light rainfall in the area is disregarded. In Nebraska, as in most of the Midwest, irrigation is supplemental to rainfall. There are, consequently, many more variables a farmer must deal with when deciding whether to invest in irrigation equipment, or even when to irrigate if he already has the means to do so.

In conversations with farmers in Nebraska, while they lay aluminum pipes through the fields the first time each year, a remark is often made that all this work would not be necessary —if only it would rain. On the other hand, the higher yield at harvest time makes the investment more than pay for itself over the years.

One of the other benefits derived from surface reservoirs is that they provide excellent recreational sites such as around Lake McConaughy or Hugh Butler Lake. Quite often, in fact, the recreational use takes precedence in the minds of a lot of people over the primary use, which is irrigation.

Perhaps one's first impression might be that with irrigation a farmer can forget his worries. True, many of them might be alleviated because he has a way of controlling growing conditions for his crops, but it is hard work, and the investment is heavy.

It takes brains, brawn, and money — brains to make sound business judgments, brawn to carry them out, and capital outlays ranging from $5,000 to $35,000 to irrigate.

And, when one forgets the business end of it all, there is the misty rainbow hovering over the land to remind the farmer that it's all part of enriching his own life, and the living conditions of those around him. THE END

THREE-COUNTY ROOSTER HUNT

With some of the best pheasant country anywhere on tap, our shooting trio harvests a bumper crop in the cornfields of ringneck-rich northeast Nebraska area

This story was written in 1963 and tells about the kind of hunting memories that are close to the heart of every sportsman. The area in which the author hunted is in northeast Nebraska, and, since the time the story was written, the author has gone back for pheasant every year. The ringneck population went down considerably since 1963, but this year there is a slight increase. Mr. Youngren is administrator of Girls Town in Omaha. Editor

YOU KNOW IN advance the chances are pretty good that something may erupt from that winding draw you are so cautiously stalking. Even so, the sudden explosion swells a king-size lump in your throat as raucous cackling ignites the atmosphere. Some birds take off running. Some soar in rocket-like fashion a few feet above the ground. Others blast skyward in a frenzy of churning wings. Nothing quite tops the action. Nebraska pheasants are on the wing.

Exciting as it sounds, this is in sharp contrast to the scanty trickle of birds that opposed me when I began hunting about 1953. My feathered trophies were so few and far between that I almost gave up. But, after years of tramping several hundred miles and invading countless fields, the odds began to change, and in 1959 things started to happen. Each day out I flushed more birds. The population suddenly seemed to mushroom. Kills came oftener and easier. I wasn't particularly concerned with the reason at the time, but I enjoyed it.

What can you expect to find in northeast Nebraska on a calm, sunny day as you search the hills and draws? Remember, weather and terrain can be your guide to where the birds are on a given day. If it is sunny and calm, you can observe the early morning ritual of the birds leaving the roosting places for a sunny hillside, while browsing over and plucking any tidbits of food that might be on the way. They'll roam at will throughout the morning. Afternoon will find them settling down in a cornfield or anywhere that offers cover and solitude. About an hour before sundown the birds will begin the final movement of the day in the general direction of the roosting areas. This provides an excellent opportunity to make up for those you may have missed during the day.

But suppose one of those infamous Nebraska winters accompanies what otherwise might be a successful season. Don't fret. A rare treat is in store for the hunter who finds the drifts piled high in northeast Nebraska. He can forget the fields and the miles of walking and devote his energies to one of the many long, tree-filled creekbeds of Thurston, Dixon, and Dakota counties. It was during this kind of hunting that our party flushed the most roosters of any outing.

We had tramped through boothigh snow for a couple of hours on one occasion, but couldn't get close to any birds. Then, a huge creek loomed between uneven cornfields. Brad Strong, a salesman from Dakota City, circled the section of land to get in at the mouth of the wide, tree filled creek bottom. Bill Strong, his brother, a lawyer from Omaha, and I took up positions on either side of the creek. A small, snake-like stream of ice looked tiny in the immense depth and width of the draw. Dried foliage and middle-aged trees protruded from the banks. My first glimpse of any movement was that of a half-dozen hens "floating" toward us. Bill signaled, and then we heard the crackling of twigs and branches. Brad was still a long way up the creek, but heading in our direction.

My heart pounded as the first batch of roosters flew right at us. I blasted off three rounds at the approaching birds as fast as I could. One rooster plummeted. Bill also fired and dropped one cock in the deep gorge below. While we fumbled for more shells, another formation winged toward us, then veered off NEBRASKAIand to the south. A hurried, three-round burst harvested nothing but a few feathers. Again and again I was caught in the frenzy of jamming shells into the gun while formations of roosters sailed within throwing distance. Indeed, we found the bird bonanza that could only be hoped for in the past.

The action lasted for about five minutes. When it was over, we gathered up seven snow-covered cocks. The survivors—they numbered in the dozens —went on about their routines. I dare say, it was a case where composure was retained more by the hunted than the hunters.

No less exciting, though, is the flank position on the downwind side of a hunting party in tall corn, when high winds all but squelch any sounds of flight the birds may make. As a result, pheasants flush within a few feet of the hunter, causing near panic even for the veteran. In northeast Nebraska, birds seem to bunch up in cornfields on windy days. Since the fields are generally small, the chances of birds sneaking out or running in circles are reduced. You can resort to the old standby. Take three or four fellows, distribute them evenly in the rows, and walk the tall corn. Be alert, be ready. Those big cocks flush in lightning-like fashion. Once they find the wind, clean hits (Continued on page 64)

INDIAN WARS CORRESPONDENT

(Continued from page 38) generally considered to be the last of the Indian Wars. Other reporters were with him at Pine Ridge. Among the more notable were C. C. Seymour for the Chicago Herald, E. E. Clark for the Chicago Tribune, Ed O'Brian for the Associated Press, and an excitable, long-winded character with a vivid imagination named C. H. Cressey for the old Omaha Bee.The journalists were there because a religious belief had become widespread amongst Indians west of the Missouri River. Followers of this belief, called the Ghost Dancers, were gathering in the Pine Ridge area, and the Indian Agency had asked for military support. The Ghost Dancers had become front-page news. The belief was that God had appeared as Christ to the white man two centuries ago, but the white man had rejected and killed him. Now the Messiah was to come to the Indians. It was a strange mixture of Christianity and Indian tribalism.

During the weeks preceding the battle, things were quiet at the Indian Agency, and the newsmen found the situation tiring. Activities seemed almost normal exce.pt for the continual strain of uncertainty during this lull before the final storm of the Indian Wars. It left the journalists with little to do but sift through a daily batch of useless rumors.

These rumors were, more often than not, brought in by Indian scouts who seemed to be more interested in telling their interrogators what they thought would please them instead of what they had actually seen. Daily reports that the Sioux were "coming in" proved untrue, and the newsmen soon learned to sift fact from fiction.

While most of the group was bored, the illustrious Mr. Cressey always found new life for a temporarily dead subject. Allen wrote that Mr. Cressey had a penchant for lurid, drawn-out stories wnich seemed to please his managing editor back at the Omaha Bee. And his stories were always a great source of amusement for his colleagues. It was probably Mr. Cressey's good nature and exciting descriptions about nothing that kept the group in good spirits and led them to poke fun at the whole situation and at themselves. They started a daily news packet and named it the Badlands Budget. Dedicating it to rumors, they wrote the most fantastic stories they could dream up to wile away the time. Often, they sent the packet to local newsmen with whom they had become acquainted in nearby border towns, and the locals loved it.

One such packet included evaluations their friends at the Indian Agency were asked to make of them. A scout named Buckskin Jack (John Russell) said of Mr. Cressey and his stories: "I've tramped the Badlands o'er and o'er, and camped on Wounded Knee; but my heart grows faint at the warriors' paint, and the lurid hue of the savage Sioux as they charge in the Omaha Bee."

During this time a medicine man at Pine Ridge was expounding the belief of the Ghost Dancers, leading them to believe that the Messiah would arrive soon. One day a strange fellow, later identified by the name Hopkins, walked into the compound and claimed to be the Indians' Messiah. Mr. Cressey, unfortunately, had gone to the railroad that morning to mail one of his colorful stories.

The Army commander at the agency heard of trie would-be Messiah and promptly slapped him in the guardhouse. One of the journalists ventured: "Cressey shouldn't have gone to the railroad this morning."

And another: 'Oh, he'll be back to wring a column or two out of this guy."

That evening, as the journalists were sitting around the table enjoying an after-dinner smoke, someone came into the dining room with a wide grin on his face. Asking what was up, they learned that Mr. Cressey, who stuttered whenever he was excited, had just returned, Upon hearing of the would-be Messiah, he had run to the commander and asked: "H-have y-you g-got C-Christ in the g-g-guardhouse?"

Next morning the agency wagon pulled up to the guardhouse. The impersonator was escorted out of jail and put into the 48 NEBRASKAland wagon with a driver. No one knows for sure, but everyone surmised he was taken to the border, placed on a southbound trail and told to keep going.

With little to do, Allen decided to quit the New York Herald and go home to Chadron. But that very evening he learned from a friend that the 7th Cavalry was supposed to leave for Wounded Knee during the night. Sioux had been sighted on the way to the same valley.

Allen told his friend that he had just wired his resignation to New York.

"That makes a difference in your favor," the friend told him. "If anything happens, you can send your stuff to as many papers as you wish, and it will have value in every office."

Allen agreed to join him. They arranged for saddle horses and a lantern so they could find the right stalls in the dark, should they have to leave in a hurry. Then they went to the parsonage and kept alternate watch for the Cavalry's departure, partially to be able to join up and go to Wounded Knee with the soldiers, and partially to protect the women and children who had congregated in the house.

But nothing happened all night. The two learned that although the Sioux were advancing, the Cavalry had decided to wait and meet the Indians at a more strategic time.

From then on, the feeling of uneasiness grew. Troops left for Wounded Knee in small groups. On the evening of Decem- ber 28, Allen was desperately trying to find a saddle horse because the next day was the time for the meeting. He finally located Mr. Swiggart, a hotel man from Gordon, who had gone north across the Nebraska-South Dakota border to watch the action. Mr. Swiggart offered to take Allen to Wounded Knee in his rig. They decided to leave that night. Allen was unhappy that he did not have his own horse, but it was the best he could do for the time being.

That evening the journalists were assembled in the hotel lobby, but only two were booted and spurred for the ride. W. F. Kelley of the Lincoln State Journal, who had been exercising his horse outside, pulled Allen aside and asked if he was going. Allen said yes, and this seemed to give Mr. Kelley the assurance he needed because he did not want to arrive there alone. The other reporter wearing boots and spurs, a Mr. Casey, took Allen into an ante-room and confided in him that he had a horse but would sooner ride in a rig, not being used to horseback. Allen jumped at the chance, asking Mr. Swiggart if it would be all right to change. Mr. Swiggart agreed. Now Allen had a horse.

That night the cavalcade began. Allen and Mr. Kelley went ahead on their horses, and passed many others on the way, some mounted, others in rigs. They went through the rolling hills on the west side of Wounded Knee Creek and found the road leading into the valley.

The first thing they did was go to the soldiers who had been there for a few days to bring themselves up to date on events thus far. Then they went off to a bluff of trees, rolled out their blankets and went to sleep. Dawn was beginning, a few hours later, when they awoke to see Indians gathering in the central area of the valley, which was the pre-arranged meeting place.

After everyone was there, the Army commander rose and told the Indians that for the time being they were being held as prisoners. He ordered them to give up their arms and told them that a government train was on its way. The Indians and their belongings would be placed on the train to be taken to a camp and cared for.

The Indians went to their tents. When they re-assembled, a woman stood behind each Sioux, a blanket which fell to the ground draped over her shoulders. There was a rifle beneath each blanket. A token number of useless weapons was offered up. Then the soldiers inspected the tents. They came across one woman lying on the ground, feigning a trance. They rolled her over and found a primed rifle beneath her.

The commander gave a speech, and the Indian interpreters replied what their leaders told them to say. Words became heated, and finally gunfire broke out. Thus began the Battle at Wounded Knee.

When bullets started flying, Allen ran up a road which led out of the valley through a break in the hills to where Captain Taylor and a group of Indian scouts were wisely staying out of the action until it came to them. He lost his breath and stopped to look back. Indians were on the road below, their backs to him. They were shooting at soldiers in the valley. Bullets coming his way were the soldiers' return fire.

He continued up the road, exhausted, and realized that the bullets coming his way were not meant for him. He decided that a stray shot would hit him just as easily if he were walking or if he were running, so he walked. On reaching the pass between the hill buttes, he came to a path which led down to a grass-covered meadow. Along the ridge he saw several companies of dismounted troops behind improvised barriers, their guns lying across the thrown-up earth. Running down the decline to where the grass was high enough for cover, he threw himself down and began crawling like an Indian.

The Sioux behind him had also arrived at the meadow and gunfire now sputtered between them and the troops on the ridge. He continued crawling toward the troops, but he did such a good job that when the soldiers spotted him they mistook him for an Indian and began shoot- ing at him. The characteristic crawl was to slide with open palm across the ground, then crook the opposite leg and bring it up just far enough to get a toehold, then lurch the body forward as close to the ground as possible to repeat the action, always with an opposite arm and leg.

At one point he dropped his pipe. His first thought was to let it be. His second was that if he ever got out of there he would need it, so he stopped long enough to retrieve it and put it in his pocket. At this time he heard three or four shots from a Hotchkiss gun, and the Indians vanished.

The soldiers stood up. Allen got up, too, and began walking toward them. He was greeted with hearty handshakes and congratulations for having kept himself alive. Several of the soldiers said they had trained their sights on him, but had missed their shots.

After the battle, Allen wrote his account and decided that, since the New York Herald had spent a considerable amount of money on him, he would send his story to that paper after all.

The next day, after finishing his copy, he gave it to a messenger who had been The Auto Club was right. The little blue lines ARE rivers!"

engaged by numerous journalists for this very job, and instructed him to go to the railroad and send it off.

In his unpublished manuscript, completed in 1938, Allen wrote: "For a long time after the distressful events at Wounded Knee, I would not permit my mind to dwell on the scenes enacted there... in this record of my varied experiences in the early West I feel something akin to ever-mounting dread as my pen draws nearer to the unavoidable subject... (but)... the record shall be completed—

"Toward the end of the first week in the New Year (1891) General Nelson E. Miles, Division Commander, moved his headquarters from Rapid City to Pine Ridge," Allen wrote.

"He soon had native emissaries expounding his conciliatory messages in all the villages. Sulking leaders came to life at once and began holding frequent councils at military headquarters, with the result that an agreement for surrender was reached.

"This was planned to be quite a spectacular affair. All of the Indian bands on the reservation assembled on the broad flat near headquarters.

"It was my intention and desire to witness this event, but the day before it occurred, I had an opportunity to ride directly across country to Chadron and decided to accept the offer. After wiring the Herald to that effect, I departed from the historic scene, thus undramatically ending the most exciting chapter of my life." THE END

HUNTERS GET THE POINT

our waders and leaving them outside the trailer door.

"How did you do?" asked Brad, who was dry and a lot warmer.

"Not too bad for an old man," I laughed. "There are three greenheads out there with your hen."

After some hot soup and a short rest, Jim was in good spirits again. The portable radio confirmed my guess about the wind — 40 miles an hour. And it was cold!

When we said the ducks were flying high, Brad suggested, "Let's go over to the goose pit. Maybe we can call some into the decoys there." Then he added, "I'm going to take along your goose gun, since I'm through shooting ducks today. Might see some geese."

My "goose gun" is a 10-gauge double barrel that kicks like a mule.

"Go ahead," I chided. "The most I ever got with that was a headache."

Once again the wind and current threatened to upset us as we waded toward the small island in the main channel. We all made it safely and set to work straightening the goose decoys and moving the duck decoys to the downwind side. Once in the pit and out of the wind, we were comfortable as I worked on the call and the boys acted as lookouts.

Jim's moment of glory wasn't long in coming as two drakes and a hen decided to have a look at the decoys. It was an easy shot as the birds just seemed to coast toward us into the wind. Jim was out of the pit and after the big greenhead almost before it hit water. He grinned from ear to ear as he held up his prize for us to see.

We stayed in the pit another hour but the flight had ended abruptly after Jim killed his duck. Finally, we headed back for the car.

On the way back to town I thought this had not been the most successful hunt we had been on, as the memory of our full-limit effort the week before testified. But Brad learned a valuable lesson in making sure of his target before shooting, and Jim killed his first duck. As for me, I thought the Experimental Point Season was great. Hunting this far west is later than in the rest of the state, and often the majority of the birds are not here until the regular season is over. If we had nothing but this late three-week season every vear, I would still be satisfied. THE END

RHYTHM METHOD FOR BASS

handle half a crank. In this fashion the worm is slowly retrieved, yet it is always dancing underwater. When a tug is felt on the line, slack must immediately be given so the bass can "mouth" the worm, turning it around as he prepares to swallow it. After a few seconds, if the line continues to move away, the hook is set and then the fun really starts. With a spin-cast reel, the system works just as easily, for the slack can be given by just pushing the button.

Surprisingly, few fish get off even with the tiny hook. An occasional worm is lost because the bass kicks it off when the hook goes in, but the barb usually catches the bass in the solid gristle around the lip. A large hook often goes in behind the lip, in the thin, tissue-like covering of the cheek. It is a rare bass that throws the small hook, for they are even hard to remove when you get the fish on the bank.

Such fishing is not for the angler who enjoys lazing in the sun half asleep waiting for a fish to nibble. Constant alertness is required, for the slightest tug probably means a bass has taken the bait, and slack line must be given right away. Until a strike, however, keep the rod twitching and counting —one, two, three, four —crank handle —one, two, etc. How much twitch to give can be determined by watching the worm in shallow water. Just jiggle the rod enough to make the worm dance along nicely.

The softer the worm, the more appealing he is undulating through the water, and the more it looks like something alive. As the retrieve nears, you can see the worm dance, and it is hard to imagine bass letting it pass by. If they are in any normal mood at all, they will grab it. Just a few days before we fished the sandpit we were working, a friend of Bert's caught five bass there with five consecutive casts to one spot. Of course he uses the same system, as almost everyone does once they try it.

"It is the ultimate system for taking bass," Bert claims. "I don't think a better method can be devised." He has been perfecting it for a long time, experimenting with hundreds of different hookups. Now, what he calls the "cadence rhythm count", or CRC has been perfected.

Bass started coming in. Luckily, I was the first to score. With a clear sky and bright sun overhead, I cast across a small cove and felt a tug. Giving line as quickly as possible, I waited, then set the hook. A healthy weight at the other end indicated my efforts were not in vain, and the slipping clutch showed he had some bulk.