NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

July 1970 50 cents RASCAL PIONEER 1,733 Ranch Owner laughed at life BEST OF DECADE Photographer selects magaizne favorites IMPRESSIONS OF WILLA CATHER ZOO'S WHO IN NEBRASKA

Master Charge your NEBRASKAland Vacation

Speak Up

STILL MORE LIONS-"After reading some comments in NEBRASKAland about sighting mountain lions in the state, I would like to add my two cents' worth. "In the fall of 1968, the day we arrived for a deer-hunting session in western Nebraska, my hunting buddies, Bob Lowther and Earl Powell, and I watched a mountain lion walk through a stubble field and into a small grove of trees about 300 yards from us.

"We reported the incident to a conservation officer the next day." —Harold L. Keller, Clinton, Iowa.

UFO-"I read Nebraska's UFO's in the March issue of NEBRASKAland with interest. I had an experience 12 or 15 years ago when I saw one of these oddities.

"About 9 p.m., I happened to go outdoors and saw what looked like a bunch of large birds, about the size of geese, sailing around our buildings. They looked orange and seemed to just float around, scarcely ever seeming to flap their wings. I watched them for some time before I called my wife. Together we watched them from our steps. They finally flew off to the southwest and disappeared. I didn't count them, but there seemed to be 10 or 12 of them bunched together." — James C. Blundell, Hemingford.

CITADEL SIGNIFICANCE - "This story ("Ageless Citadel", April 1970) is of special significance for my wife and I. From JULY 1970 October 1952 through August 1954, we were stationed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. I was a teacher in the Indian Service under the Department of Interior, and as such, taught in the Oglala Community High School at Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

"During the time we were there, we drove over this scenic landmark on our way to Chadron. We never knew it as 'Beaver Wall', but as The Great Wall of China.'

"Until such time as we return, that issue of the publication will refresh our memories." —L. D. Fairbairn, Hemet, California.

CATTAIL COOKERY-"I have been looking for a recipe for cooking cattails. Could you please send me any recipes that you may have, or information on who would have such a recipe." —Christine Landkamer, Burwell.

Lou Ell, our wilderness expert and chief photographer, came up with the answer to your inquiry about cooking cattails. He claims the roots are excellent substitutes for potatoes.

Pale, yellowish-white cones, jutting from the roots, are buds of new stalks and are good in salads. These sprouts can also be boiled in a cream sauce, similar to asparagus tips, for a vegetable dish. As for the roots themselves, scrape the "hair" from the tubers and cut the large pieces into manageable chunks, washing well. Cover with salted water and boil. When tender, they are ready to serve. -Editor.

A CAT A DAY-"As a boy in Alliance, I was a great lover of animals. My uncle, a rancher at Ekalaka, Montana, was a trapper of gray wolves for the bounty and pelts. I begged him to send me a wolf pup. He shipped me a very young female and I raised her to a full-grown animal. A few of my problems follow:

"We had a fenced-in three-lot yard on Laramie Avenue near the high school. I built a kennel and kept my wolf on a long chain. As she grew, she became attached to me and I could play with her like a dog except when she was eating, then no one could approach her. She grew to a large animal, and when she put her front feet on my father's shoulder her head extended higher than his. He was 5 feet, 10 inches tall. A friend of my father's had a flock of greyhounds with which he hunted coyotes. He thought three of them could handle the wolf. I accepted the challenge and released her, she backed into a corner of the fence, and when the three came in for the kill she slashed each of them so furiously they quickly jumped over the fence. I am sure no dog can overcome a gray wolf.

"She became a very difficult feeding problem and occasionally would wear out the chain and go hunting. I would be called out of high school to retrieve my wolf and usually found her in some farmyard with a number of killed chickens. Even though I collected scraps from restaurants and meat markets I couldn't keep up with her appetite.

"Hungry as a wolf is a true expression. One day a cat ran in front of her and she pounced upon it and in a minute devoured it completely. Since I had no love for cats, I thought my feeding problem was solved, so I started collecting a stray cat a day to feed the wolf. This was successful for a time until some housewives missed their pussy cats and arranged a meeting with Mayor Harris. I was called to the meeting and ordered to get rid of my wolf. After pondering how to dispose of her, I wrote the city park in Denver and offered her for sale. The zoo manager offered me $15, but I held out for $25 and got it. Some months later on a trip to Denver with my father I visited the zoo and the wolf recognized me. She came to the front of the cage and played with me." —A. Elting Bennett, M.D., Berkeley, California.

SIX-MAN FOOTBALL-'This game ("Speak Up", February 1970) was developed by a Mr. Bruce Eppler. As a lad, he lived in Alliance, where his father was a minister. There were three children, two boys and a girl. "The family came out to my parents' place in the country to visit and I became acquainted with the boys. They were older than I. Then, when I went to town to school in the late 1920's, the six-man football was starting in small schools. At that time, there was a lot of comment in our high school regarding this game." —Phil Lawrence, Alliance.

CAPITOL MEMORIES-"The pictures of the Nebraska State Capitol (April 1970) brought back memories of 1920. I was the inspector on the second floor of this 'Wonder of the World.'

"Kingsley Dam at Lake McConaughy also brings back memories. I was one of the surveyors for the U.S. Reclamation Service in 1921 and 1922 for the preliminary investigations for power and irrigation possibilities from Kearney and Hastings west toward Lemoyne." — Jack D. Gavenman, St. Louis, Missouri.

STRAIGHT FACTS-"Last weekend, I returned to my reservation (Santee). My

brother, Albert Thomas, proudly showed

me your NEBRASKAland Magazine

with his picture beside the historical

marker of Standing Bear, south of Niobrara. I told Albert what was wrong with

it. First, the name Albert Thomas wasn't

identified. It was just like another cigarstore Indian. It, also, should be on the

cover and not in the back of your magazine.

3

This, to me, shows that you are

hiding the real facts or you just didn't

know the truth about Indians. If you

don't know the real facts don't print it.

"Basically the inscription of Standing

Bear didn't tell the real truth. Standing

Bear said, The U.S. Constitution was

never meant for the Indians.' This statement made Gen. Crooke cry like a baby.

It was Abraham Lincoln who signed the

Homestead Act of 1862, which opened

the West for settlement of stolen Indian

land. The coverup, blaming the Sioux

for taking land from the Poncas, is untrue.

This, to me, shows that you are

hiding the real facts or you just didn't

know the truth about Indians. If you

don't know the real facts don't print it.

"Basically the inscription of Standing

Bear didn't tell the real truth. Standing

Bear said, The U.S. Constitution was

never meant for the Indians.' This statement made Gen. Crooke cry like a baby.

It was Abraham Lincoln who signed the

Homestead Act of 1862, which opened

the West for settlement of stolen Indian

land. The coverup, blaming the Sioux

for taking land from the Poncas, is untrue.

"If you want to know my hobby ask Danny Liska and Emil Leypoldt, both members of the Outdoor Writers Association, also one of the radio announcers in Lincoln, Dominick Costello. They know who I am." —Walter Abraham (Walking Buffalo), Worthington, Minnesota.

Thank you for your letter and comments on NEBRASKAland. We are always happy to hear from those who are concerned with our state magazine and its content.

Your comments on the position of the April historical marker prompted some investigation, both in our department and at the State Historical Society. It is a magazine policy that the historical marker usually be on the inside back cover of issues in which it is used. And, the people in the photograph are never identified. They are used to add emphasis to the picture and are not entities unto themselves. You are correct that the Homestead Act was enacted in 1862 and it was President Lincoln who signed it. However, there is no direct reference to that signing in either the explanatory material concerning the picture, or the marker itself. Concerning the facts in the copy, all were taken from official publications of the State Historical Society. On receipt of your letter, I rechecked these facts with that agency and found them to be accurate. As you know, the Nebraska Historical Society is the most reliable authority on historical happenings in the state. You might also be interested in knowing that all historical items which appear in the magazine are checked and cleared through informed sources on that subject. This means either the Historical Society, or, if possible, contacts who lived through the period in question and were acquainted with the event. — Editor

TOT TEACHER-"NEBRASKAland is more and more finding its way into the classroom as fourth graders study their state. It is a great help. However, it could be of still more help to the children if all of it were not written for adult consumption. "Would it be possible to have a feature each month just for the child in the middle elementary grades and written on the childrens' vocabulary level? I am sure this added feature would make the magazine even more popular at school as well as at home."—Henrietta Kruger, Norfolk.

TRUE STORY-"This is the way it happened to a guy that did not lie."—Donald Plambeck, Lincoln.

INNOCENT OF GUILT While I was fishing just south of Crete On the bank a game warden slowly walked his beat. While I was baiting hooks in the grass He watched me through his spyglass. I had taken off hooks that numbered eleven But on one line I had just put seven. I really didn't know it at the time But five hooks is the limit on any one line. I went back to the cabin and in a little while Here came three game wardens wearing a big smile. They went by the cabin on down to the point I supposed they were just looking over the joint. Then they came back and we started to chat I told them my name was Pat. They asked me if I fished — and I said sure That answer made me much wiser but poorer. I told them I had seven hooks on a line I really didn't know that it was a crime. We got in the car and went down to the river By this time my knees had started to quiver. I really didn't know I had broken a rule But these guys were making me feel like a fool. I pulled up the line — it was just as I said and about that time I wished I were dead. They rolled up the line on a twig I knew then in my pocket I would have to dig. I went to town and paid my fine For having seven hooks on that one line. Now the county can keep the money And the warden can have his fame But how ami going to get back my good name? NEBRASKAlandGo Adventuring!

This is the Old West Trail country, big and full of doing. Stretching from one end of the setting sun to the other, this inviting vacationland will ever be the place for your family to go adventuring. Here, the horizon-wide scenic vistas defy description. The trail is a series of modern day highways, mapped out by state travel experts. Look for the distinctive blue and white buffalo head signs which mark the Old West Trail. Sound inviting? You can bet it is! Go adventuring on the Old West trail! For free brochure write: OLD WEST TRAIL NEBRASKAland State Capitol Lincoln, Nebr. 68509 WEST Name Address City State ZipFISHING. . . A FAMILY AFFAIR

Discover each other and NEBRASKAland...

For family fun, NEBRASKAland's great outdoors is the place to be. There's no generation gap on the shores of a sparkling lake or rushing stream. There, everyone speaks the same language — the language of Nature. There's nothing quite like the aroma of fresh fish sizzling in the pan over an open fire to draw folks together. Mom, Pop, Sis, and Brother can all get hooked on the family affair of fishing. To make the excursion more productive, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has published a free brochure, "Where the Fish Are". For your copy write to NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, 68509. And, your friendly, neighborhood permit vendor has the tickets for months of pleasure. Remember, the family that fishes together, grows together.

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

Wilber invites you!

... have the time of your life where fun is just a way of life

For the Record... MAYBE TOMORROW

Water is summer fun and recreation. There are more "recreationable" water areas now open to the general public than there ever have been. So, there it is. Let's enjoy it and continue to enjoy it through recreation areas made available to us.

If, in this Age of Aquarius, you are to use your water areas wisely, listen to some thoughts we have.

First, learn to swim this summer. It is not hard to find instruction. If you live in cities, there are recreation pools, school pools (which should be open in summertime, too), YMCA's, boys' clubs, girls' clubs, and other swim clubs. The Red Cross teaches swimming almost anyplace where there is water. If you are in a rural community, Red Cross instructors will teach you in a portable pool which they may bring to the little red schoolhouse. Civic organizations and 4-H clubs sometimes purchase such pools for as low as $100.

Now, you do not have to be a certified instructor to teach your own family, although it helps to take a course. The newest of these instruction methods is a do-it-yourself sort of technique called "Drownproofing", developed by Fred Lanoue of Georgia Tech. Parts of this technique have been adopted by the Navy, Marines, Scouts, YMCA, Red Cross, Coast Guard, and Peace Corps.

In Drownproofing, you learn to hold your breath while floating face down, relaxed, then using any kind of simple kick or armstroke to come up for air. You can float like this for an hour or a day, or until you wish to stop. You also learn to modify the technique slightly so that you can swim long distances easily, handle cramps and injuries, and enjoy water fun safely.

Still, there are plans to be made. Foremost, do not do these things alone. A Drownproofing course may make you feel like a water master, but we humans are not natural water animals. We can be caught in the water very easily.

Such things as diving injuries, fainting, cramps, collisions, or being grabbed by a person in panic can, and do happen. To avoid these, use a few simple rules:

• Never swim alone; you could use a little help someday. • Participate with an able and knowledgeable partner. Father-son outings are fine, unless the father should really need help some day from a stronger person. • Become familiar with rescue and resuscitation techniques. You can become as efficient, with practice, as a policeman or fireman. Be sure there is at least one person in your family who is a capable rescuer. • Know the area where you are playing—the currents, obstacles, depths, weather signs, and location of rescue stations or equipment. • Get instructions on equipment use from power squadrons, scuba instructors, or agencies such as the Red Cross. Always have one life jacket for each person in a boat and make a non-swimmer wear it on water. If you are the kind of person who overloads a boat, you need psychiatric help, a good lawyer, a lot of insurance, and patience to see you through a jail sentence for criminal negligence.Have your water fun, now that you have made it to the Aquarian Age. Have it reasonably. Be considerate of others, and you will continue to enjoy water sport —the world's foremost recreational activity.

John Foster University of Alabama July 1970For your NEBRASKAland Vacation— RENT-A-HERTZ

Starring the Radiant

Starlite Tub/ShowerTRAVEL TIP OF THE MONTH

Whether you speak Czech or not, you'll have two days of fun-filled relaxation in Wilber. See their people in Czech costumes dancing the beseda. Colorful parades and pageant will make this weekend an unforgettable experience for the whole family.Once Bitten, Twice Shy

I WAS HURRYING up the path from Medicine Creek Reservoir to our cabin after setting out my catfishing jugs. My husband Harley was behind me on the path, herding the family dog who puttered along on his short legs.

About halfway up the 50-yard path to the cabin, something scratched my foot. "Probably a thistle or wire," I thought to myself. Then, after taking several steps, I thought the dog would probably also get tangled in whatever it was, so I went back to pick up the offending snag.

It was nearly dusk that July 19 afternoon back in 1964 when I saw the snake. It was coiled and hissing like a demon. I knew immediately what had scratched my foot. A rattlesnake!

My husband was still below on the path, but he came running when I yelled, "A rattlesnake! It bit me!"

The neighbor in the next cabin, Art Herrman, also heard and came running. The snake was mad, but never shook his rattles. He just kept hissing. It's lucky he did or I may have been struck a second time when I returned to the spot.

While Mr. Herrman rounded up weapons to kill the snake, I rushed to the cabin for my snakebite kit. I cut across the fang marks and applied the rubber suction cup while Harley called the community hospital at Cambridge. Mr. Herrman, a McCook mortician, had his ambulance at the lake so he used it to take me into town. We got to the hospital only 17 minutes after I was bitten, but the venom was already doing its work.

Dr. R. R. Morgan was an old hand at snakebite treatment. He had done considerable research in Arizona and had treated hundreds of victims. My case looked like a lost one, he told me later, but a test for serum compatability was quickly made and antivenin quickly administered. Pain came quickly, though. Despite the suction cup, which is not effective unless the wound is cut deeper than the puncture marks, a large dose of venom was coursing through my blood stream. The puncture marks were on my right instep, just above the edge of my canvas shoe. Shortly after our arrival at the hospital I went into severe shock.

I was told later that it was touch and go there for a while. One minute my pulse and blood pressure were there, and the next moment they were gone. For several minutes the NEBRASKAland

After the severe pain, nausea, and shock had passed, recovery began. This took several weeks. Following two weeks of treatment at the hospital I was allowed to go home, but only on the condition that I remain in bed. It was another four weeks before I recovered sufficiently to get around and it was much longer before I was completely over the ordeal.

Since my snakebite episode, dozens of people have told me their stories. I become frightened all over again each time I listen to one of them, but also more thankful. I always recall the event as I was going up to my cabin that fateful day. I met four girls in swim suits going down to the lake at the time. They JULY 1970 could just as easily have been bitten as I.

Snakes seem to be on the increase in some areas, and I wish people could be made aware of the dangers without being too alarmed. In the United States, nearly 7,000 persons are bitten by poisonous snakes each year, and while only about 15 die, many others suffer tissue damage, disfigurement, pain, and sometimes amputation. I read about research at the University of Utah to perfect a vaccine to protect against snakebite. I hope it comes soon.

My experience has made me more cautious. I now carry a stick which I "rattle" in the brush as I walk. This is normally enough to cause the snakes to scurry away.

Perhaps the old adage about "once bitten, twice shy" really does pertain to me, because I try to give the snakes every opportunity to clear out of the area before I go walking now. THE END

WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM 11

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . STRIPED SKUNK

Often thought of as "stinkers in the wild", these creatures are harmless and mostly unharmed. Man and autos are the only efficient predators

THE SAD THING about skunks is that they have never mastered a defense against the automobile. Their slow, flatfooted, waddling gait and reluctance to give ground to anything accounts for the numerous carcasses seen along highways. These road kills and the obnoxious scent familiar to almost everyone are the most common signs of skunk presence.

The skunk is basically a black animal with a blaze of white on its forehead and a white mantle across its nape and shoulder, which separates into two broad stripes running back along its sides. The long, bushy tail is black and white. There is much variation in the color pattern with some individuals completely black, except for a patch of white on the top and back of the head. All color variations can be found in a single litter.

Skunks have short legs and small eyes and these, combined with a stout body, give them the appearance of tiny bears except for the prominent, long-haired tail. Weights range from 3 1/2 to 10 pounds with males being heaviest.

The saying "speak softly but carry a big stick" can well be applied to Mephitis mephitis (which, by the way, means "a noxious or pestilential exhalation from the ground"). The source of this power is two small glands about half an inch in diameter, located at the base of the tail on either side of the anus. The glands contain about one tablespoon of thick, volatile, oily fluid which is sufficient for five or six rounds. The 12 fluid, containing an organic sulphur dioxide compound called butyl mercaptan, is produced at a rate of about a third of an ounce per week.

For the uninitiated, the scent will not cause permanent harm to the skin or eyes, although it will sting unmercifully for a short time. It has phenomenal lasting qualities but in dilute form does not smell too bad. A good many upland game hunters who use dogs have ended a hunt with the dog riding in the trunk or waiting for a pickup to haul him home. For many weeks after, moisture or just damp air will bring back the odor.

Remedies to help remove the scent from people and clothing probably number a million or so. For clothing, washing in gasoline, ammonia, chloride of lime, benzine, or common laundry bleaches will help. On a person or animal, the application of equal parts of oil of citronella and oil of bergamot or a dilute solution of sodium hypochlorite is helpful in neutralizing the scent. You will probably find the smell very difficult to erase, no matter what you use.

The striped skunk, one of four species of skunk, is prolific and adaptive. It is found in every one of the "Contiguous 48". The only other Nebraska skunk is the spotted, a much smaller, slimmer, and more agile animal. Connoisseurs of such things claim the spotted skunk's scent is "keener" with more of a "bite" to it, not as mellow as that of the striped skunk. Numbers of striped skunks vary from year to year, with populations building to peaks which are then drastically reduced by disease. While rabies may reach epidemic proportions in skunks, other diseases are believed to be more important.

Striped skunks are essentially nocturnal animals, ordinarily leaving their burrows about dusk. Any skunk observed abroad in daylight should be considered to be acting abnormally and should be treated very carefully due to the possibility of rabies.

They prefer habitat such as forest borders, brushy field corners, fencerows, and open grassy fields broken by wooded gullies. They normally live in ground dens, dug and discarded by badgers and woodchucks, but will also dig their own on occasion. Abandoned farmsteads are prime den sites. The living quarters are usually furnished with leaves and dry grass. Their "world" is normally about 1 to V/i miles in diameter, although males during the breeding season may cover 4 or 5 miles in a night. Maximum ground speed is about seven or eight miles an hour, or slow enough for inquisitive kids to get in trouble. They are poor tree climbers and swim only when absolutely necessary.

Skunks are omnivorous, eating almost anything, with preference shown for insects and small rodents. Fruits and berries are taken, as are eggs, frogs, nesting birds, and carrion. They will occasionally raid a beehive or a hen house, but generally cause very little trouble to anyone.

By winter, the skunk is well padded with fat, sleek with a prime pelt, and ready for hibernation. It is not the deathlike hibernation of the woodchuck, but more like that of the bear.

The breeding season starts in February and the gestation period averages about 63 days. Only 1 litter a year is produced, but it may contain up to 16 young. Four to six is the common number. Larger, older females tend to have the biggest litters. The young, born in May, are wrinkled, about as hairy as a peach, and weigh around half an ounce each.

Many predators will kill and eat skunks, but only when pressed by starvation. The great horned owl is one predator that seems to take skunks most frequently. Man is, thus, the only efficient predator. In past years pelt prices were good and skunks were taken. But by the early 1950's, trapping declined. THE END

NEBRASKAland

CAMPING CAMARADERIE

A century ago, fires burned low along the Platte River Valley. Now a new breed renews those flames

SINCE EARLY DAYS, more than 100 years ago, campfires glowed along the great Platte River road across Nebraska. Wagon trains were moving west and people found a sense of safety in numbers. Those campfires have now been replaced by the glow of electric lights from another kind of camper.

Today trail blazers ride in speedy vehicles and take their victuals and survival equipment along in a tent trailer, camper trailer, or pickup camper. But despite technology they still find safety in numbers —camping clubs. Nebraska offers an almost unlimited assortment of clubs for out-door-lovers from commercial groups to national clubs to local, unchartered 14 organizations. Each of these offers one advantage — outdoor companionship.

The largest of the Nebraska groups is the state branch of the National Campers and Hikers Association (NCHA). Started by 3 families about 15 years ago, NCHA has expanded to about 47,000 in the United States and Canada. There are about 500 families affiliated with the 17 chapters of NCHA in Nebraska.

There are no requirements for membership. Any kind of camping rig is welcome, from tents to mobile homes. Despite its tremendous growth, the camping organization has retained its original traditions. All NCHA clubs meet one camping weekend a month during the summer season. In winter they meet one evening a month.

Camp-out programming is traditional. The Saturday night dinner is a potluck affair followed by a campfire get-together. In the Omaha Explorer chapter, the men sometimes cook for the whole camp. Sunday begins with some kind of open-air church service, and the remainder of the camp-out is devoted to individual outdoor - appreciation and social activities.

All NCHA chapters aren't American melting pots. Some are chartered for a specific purpose such as a senior citizens' group or a rock collectors' club. Whatever their foundation, they base their good times on courtesy and public service. Each spring all chapters have a special litter pick-up camp-out when members concentrate on clearing a state park or other camping area of its accumulation of garbage. Club leadership always stresses clean-up and members are urged to leave their camping areas spotless.

A portion of NCHA membership dues is devoted to a national scholarship fund. Each year two scholarships are awarded to the children of NCHA members who will study a conservation-related field. NCHA lobbyists support the Golden Eagle passport, which is before Congress for renewal. The Golden Eagle permits its holder to enter all national parks without paying entrance charges. Like a season swimming pass, the passport may be purchased at the beginning of the season for continuous admission.

Among its many other activities, NCHA holds a national camp-out each year. A teen queen is chosen at this camp-out and in 1967 she was a Nebraska girl, Molly Mendon of Omaha. To win her title, Molly won chapter and state contests before going on to the national. She competed in both swimsuit and talent contests. A gown and full wardrobe were donated as prizes by Sears Roebuck and Co.

The Omaha Family Campers group is similar in most aspects to NCHA chapters. It is not affiliated with any national or state group, however. Like NCHA, Family Campers has potluck suppers and Sunday church services. They hold weekend camp-outs from April to October like the other groups.

In May and September the potluck is a chicken barbecue. Individual members bring complimentary dishes. When action begins to wane, things like horseshoe pitching contests and dog shows take over. Such competition is a delight, too, for those (Continued on page 53)

NEBRASKAlandYour favorite photo could win a 14-day vacation on us!

Your top, color photo or slide can be your ticket to 14 days of fun-filled travel to the places "where it happened". The grand prize winner and his family will lasso a "perfect" fly-drive vacation in scenic and historic NEBRASKAland. From the Gateway City of Omaha to the picturesque wonders of the Pine Ridge, this all-expense-paid trip will take in the rich lore of the Old West.

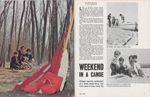

WEEKEND IN A CANOE

Bridges become guideposts as a family floats along, free from cares of busy home life

LIKE A FLOOD, spring flowed through the Platte Valley. Cascading green of new grasses tumbled through ravines and gulches. Songbirds, resounding with the chatter and babble of skipping brooks, coursed along the budding shore. Nature was fluid and all life came alive with the excitement of the season.

The fever of spring had spread in my family and now we, too, joined the flow of the season as we glided along the Platte River. Our weekend of canoeing began well.

A few minutes earlier we had completed our preparations and shoved off. Our "put-in" spot was up the river from Fremont at the Fremont Lakes State Recreation Area. We loaded our gear, including everything that we would need for an overnight camp. My wife, Annette, was in the bow. I manned the stern. Our two children, Charles, eight, and Jennifer, three, were side by side in the middle.

With the stealth of the Indians who used to ply this section of the river, we eased along the shore, enjoying the sights and sounds of the woods coming alive. While our predecessors used bark, hide, and dugout crafts, ours was a sleek, molded-plastic canoe.

Indians used to rely on natural features such as large or unusual trees, a prominent bluff, or a bend in the channel to keep their bearings. We relied on man-made objects, especially bridges. When traveling on a river, these spans are often the most obvious landmarks. They can be a welcome sight if they mark the end of a hard day's canoeing.

Our trip was planned for leisurely travel. I had done this part of the Platte River before with our canoeing club, the JULY 1970

Midwest Canoe Association, so I had a

pretty good idea what the river was like.

Midwest Canoe Association, so I had a

pretty good idea what the river was like.

Many of the trees along the bank had been felled and stumps of all sizes stood around in every direction.

"What happened to these trees, dad?" Chuck asked. "Beavers cut them down," I replied. "You can see the toothmarks if you look closely."

There were signs of beaver activity all along the river. They gnaw down the cottonwoods and willows for the leaves, young shoots, and bark, all part of their regular diet. We could also see the paths these large rodents make through the grass on their way down the slopes of the riverbanks to the water. Beaver must occasionally have eyes bigger than their stomachs because often there is a large trunk cut only half-way through. They probably become impatient for dinner and wait until another day to complete the job.

Our tasks were also being put off to another day now. As we drifted farther down the river we heard and then spotted an airboat. These shallow-draft boats, driven by airplane propellers from the rear, are a more familiar sight in the Everglades than in Nebraska, but there are many of them along the Platte. Except for canoes, airboats are about the only type of boat that can maneuver in this shallow river.

The shallowness of the Platte makes it necessary to keep a sharp eye on the flow of the current. If you miss a change in the channel as it crosses from one side of the river to the other, you might wind up dragging the canoe across a sandbar. While much of the river did offer us the eight inches of water we needed, we were able to travel a lot easier by staying in the main channel.

When we did venture into the slower backwaters, we saw a variety of wildlife. A solitary great, blue heron made short flights downstream, and ducks took off in pairs as we approached them. Carp were spawning in the shallows, while muskrats ferried to and fro.

Jennifer brought us back to the reality of our trip.

"I'm hungry," piped up my daughter. Tm with you, Jen," I smiled. "We'll stop for lunch at the next good spot."

It didn't take long to find one. A high sandy area near a gravel pit was our luncheon setting. Annette had prepared sandwiches and other goodies before we left. Besides satisfying our appetites, the break gave us all a chance to stretch our legs and relax.

This restful mood continued even as we went on our way downriver again. The peacefulness of the warm spring day quickly caught up with the kids and they soon fell asleep. What more perfect spot could be found for an afternoon nap than in a gently rocking canoe with a perfect combination of the sun's warmth and the river's cool breezes.

"Look back through those trees," I 18 whispered to Annette so as not to wake the kids.

As I spoke, the deer I was pointing out caught her eye.

"I see him," she replied, "and look, there's another on the other side of the river."

Not all life along the river was animal life, of course. Lots of folks have cottages and camps on the Platte and many were in the process of getting them ready for the coming summer. Some of them were base camps for the hunting season since blinds decorated their front lawns, attesting to the Platte's waterfowl-hunting reputation. Unfortunately, man's presence along this beautiful stream can be seen in other ways. Trash and junk litter several areas along the Platte. Old automobiles, while they do apparently help prevent erosion of the banks, often ruin the scenic features of what could be one of the state's really attractive rivers.

Of course, the real beauty of a canoe trip such as ours lies in the freedom and solitude that almost every stream offers. Often oblivious to our surroundings, we drifted along like a chip with the tide. Occasionally the spell would be broken and we would have to rely on our canoeing skills to keep out of trouble. A sunken log, a fallen tree, or a hidden piece of debris would require quick paddling or a precise turn from the stern to swing us around. Also, if the wind turned against us it would take hard, steady strokes to keep us headed in the right direction.

It was a change in the wind that made us notice the darkening skies toward the south. A brisk breeze had come up and before we realized it, the beginning of a storm was overhead. In the distance, lightning etched the billowing clouds in brightness. We hastened now to reach our planned stopping point. The highway 92 bridge appeared in the distance. Just beyond it was our destination, Two Rivers State Recreation Area.

As we pulled the canoe up the bank, the first drops of rain started to fall. Our pop-up tent was quickly erected and our gear placed under cover. Hot dogs were on the supper menu, so we started a fire. But just as it got going, as if on cue, the storm began in earnest. Intermittent showers throughout the evening kept us scurrying back and forth to the safety of our tent. Despite the rain, we had a good night's rest.

By morning the spring storm had passed and we were soon up, with the prospect of another pleasant day for canoeing. Breakfast was topped with hot chocolate.

Once again we turned our attention to the river.

"It looks like it came up a little during the night," Annette noted. "I think you're right," I agreed. "Last night's rain must be responsible."

But the Platte, even when high, is still a shallow river. Not long after we had shoved off, (Continued on page 59)

NEBRASKAland

RASCAL RANCHER

H. D. Watson's zany career spanned parts of two centuries to create an empire destined to fall

YOU PROBABLY couldn't call H. D. Watson a shyster. But when he wandered into Kearney in 1886, he was about as adept at pettifoggery as anyone around. It is said that he was an extremely generous manias long as his generosity didn't cost him anything. In fact, there was little chance it would, since he seldom had any money. But he did have enough cash to become what was later called the 'last of Nebraska's great land barons".

The year Watson arrived in his adopted city, Kearney was booming. Business was in high gear and expected to remain there. That same year, Chicago was writhing under the bloody Haymarket Riots, Geronimo surrendered, fled, and was recaptured, and Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle created supersleuth Sherlock Holmes. So, the neatly (Continued on page 55)

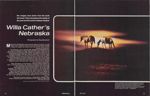

Willa Cather's Nebraska

Her images were drawn from the earth she loved. They encompass the sweep of the land and the wind's restless freedom

MOVING TO NEBRASKA from the gentle climate of Virginia, a young Willa Cather, exposed to this raw, new earth, discovered in herself a desire to capture the elusive force this land of strong contrast exerted on its pioneers.

Her Nebraska works, especially My Antonia and O Pioneers are, as a result, biographies not only of the characters they contain, but the land itself. The introduction of My Antonia, for example, which has two old childhood friends meeting on a train, establishes this theme of the dominant landscape: "We were talking about what it is like to spend one's childhood in little towns like these, buried in wheat and corn, under stimulating extremes of climate: burning summers when the world lies green and billowly beneath a brilliant sky, when one is fairly stifled in vegetation, in the color and smell of strong weeds and heavy harvests; blustery winters with little snow, when the whole country is stripped bare and grey as sheet-iron."

These descriptions of the Nebraska landscape helped establish the West in American literature. Her imagery encompasses the sweep of the land and duplicates the restless freedom of the wind itself. "When spring came, after that hard winter," she writes in My Antonia, "one could not get enough of the nimble air. Every morning I wakened with a fresh consciousness that winter was over. There were none of the signs of spring for which I used to watch in Virginia, no budding woods or blooming gardens. There was only spring itself; the throb of it, the light restlessness, the vital essence of it everywhere; in the sky, in the swift clouds, in the pale sunshine, and in the warm, high wind. . . "

The following pages represent a photographic reading of Miss Cather's Nebraska prose, interpretations of the images she drew from the earth she loved.

Quotations courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Company and Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 22 NEBRASKAland

TEACHERS ON THE TRAIL

A century of history unfolds during journey as educators get new slant on Nebraska's past

28THIRTY-SIX NEBRASKA teachers have come face to face with the Sand Hills. And, like the pioneers before them, they found the "hills" a formidable challenge as the sandy tracks sucked the wheels of their mighty bus ever deeper.

Modern transportation has not yet completely conquered the "highways" of the Sand Hills. Residents know that and gingerly drive their vehicles to the side of regularly traveled trails or throw hay in the tracks. But, our group on the Fourth Annual University of Nebraska Summer Session Tour of Nebraska was like any other band of tourists. Consequently, we were introduced to one of man's earliest means of transportation -WALKING.

Our guide had recommended a shortcut from the Haumont sod house, north of Broken Bow, to Sargent, thus providing an opportunity to test sand against machine. Needless to say, the machine NEBRASKAland lost to what appeared to be a level, harmless half-mile stretch of well-traveled sand. The only solution was to unload and apply "teacher power" to the back of the bus.

Suddenly free from the grasping sand, the driver, either in a sudden and insidious impulse to escape his passengers or to get to more hospitable terrain, expressed his appreciation to the pushers by blasting forward full throttle leaving behind a cloud of brown sand and black diesel exhaust.

This was but one of the more colorful episodes that dotted our tour, which is part of a three-week workshop at the University that is designed to give students experiences which will prepare them to teach history more effectively. At the same time, the face-to-face confrontation with "where it happened" subtly changes attitudes about the state and its heritage.

The workshop and tour were both based on four major points: (1) history is all around us and can be found in every community, especially by talking to people who have lived through it, (2) students learn history best when they can identify with it, (3) there are blueprints to understanding history, particularly first-hand observations and the proper tools and resources, and (4) students learn history best when they can discover it for themselves.

The first phases of the workshop are devoted to studying local history and to research. Recommended reading included Faulkner's Roundup, Neihardt's Black Elk Speaks, Fitzpatrick's Nebraska Place Names, Olson's History of Nebraska, and Mari Sandoz' Old Jules, Crazy Horse, and Cheyenne Autumn.

To prepare for the trip, the class divided into small groups, each of which researched the history of counties along the route and reported back both before and during the tour. Thus, we were oriented to the topography, utilization of the land, settlement of the people, development, and historic sites and incidents. Handouts were distributed by each group on the bus and oral reports provided still more information.

One diligent researcher came up with the rules for riding on a stagecoach, which seemed appropriate to our trip.

(1). Abstinence from liquor is requested, but if you must drink, share the bottle. To do otherwise makes you appear selfish and unneighborly.

(2). If Ladies are present, Gentlemen are urged to forego smoking cigars and pipes as the odor of same is repugnant to the Gentle Sex. Chewing tobacco is permitted, but spit WITH the wind, not against it.

(3). Gentlemen must refrain from the use of rough language in the pres- ence of Ladies and Children.

(4). Buffalo robes are provided for your comfort during cold weather. Hogging robes will not be tolerated and the offender will be made to ride with the driver.

(5). Don't snore loudly while sleeping or use your fellow passenger's JULY 1970

(6). Firearms may be kept on your person for use in emergencies. Do not fire them for pleasure or shoot at wild animals as the sound riles the horses.

(7). In the event of runaway horses, remain calm. Leaping from the coach in panic will leave you injured, at the mercy of the elements, hostile Indians, and hungry coyotes.

(8). Forbidden topics of discussion are Stagecoach robberies and Indian uprisings.

(9). Gents guilty of unchivalrous behavior toward lady passengers will be put off the stage. It's a long walk back. A word to the wise is sufficient.

Phillip * Dowse boarded the bus to act as guide for our excursion to Comstock, the first major stop. Nearly a century of history unfolded before our eyes as he pointed out such sites as the abandoned town of Wescott, one of nearly half of the Custer County settlements that no longer exist.

As teachers, we were particularly interested in the site of the first school in Custer County, which had been dug into the side of a bank and completed with sod. At Fort Garber, we learned the post was built in 1876 to protect 12 families from the (Continued on page 52)

Zoo's Who

Animals of every description jam the grounds of these hubs of Nebraska fun. Be you 6 or 60, there is a treat in store

RUMBLING ROARS of an African lion echo through the streets of Scottsbluff almost daily, while in Lincoln a chimpanzee comically roller skates through Antelope Park. And in Omaha, a huge gorilla loudly thumps his chest. Meanwhile, scores of children cuddle honest-to-goodness "billy" goats in Crystal Springs Park at Fairbury. All of this seemingly off-beat activity is merely routine in NEBRASKAland's many zoos and wildlife parks.

Zoo is a small word, actually a shortening of the phrase zoological garden which is a garden or park where wild animals are kept for exhibition. Although it is small in size, the word zoo has plenty of meaning. Most importantly, of course, it means animals. But its implications and responsibilities extend much further. A zoo means people — those who visit, those who study there, and those who work there. It also means organization, buildings, land, exhibit areas, education, and great dedication by individuals and communities. These meanings and responsibilities are extended to Nebraska's many wildlife parks.

To say that Nebraskans and their visitors show interest in animal exhibition facilities could easily be construed as the understatement of the year. Conservative estimates show that some 1 1/2-million people scurried to Nebraska's zoos and wildlife parks last year seeking education and amusement.

Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo led the field of attendance in 1969 with over 350,000 visitors passing through its gates during the regular season from April 1 to November 1. Visitors there witnessed a vast array of animals, birds, and reptiles amidst a planned total zoo investment of nearly $8 million. To date, the Henry Doorly Zoo complex is nearing the midway mark of completion.

Encompassing some 108 acres, displays at Henry Doorly run the gamut from bantam roosters to rare orangutans. Spokesmen for the zoo explain that their primary specialization is rare and endangered hoof stock and great apes. However, a general visitor might find that hard to believe in observing the overall thoroughness of the zoo. Over 500 specimens are now on exhibit and, of course, there's more to come.

One of the most talked about displays at the zoo is Casey, a huge gorilla, and his mate Bridgette. The pair was blessed with a little one called Miss Vicki earlier this year. Unfortunately, the baby gorilla died June 3, a sad loss for administrators and an even bigger loss for the millions who visit here each year.

Officials at Henry Doorly consider the number two favorite the zoo's "live steam" model train. The train is a slightly larger than half-scale model of the Union Pacific No. 119 which pulled the ceremonial cars to Promontory, Utah, for the golden-spike ceremony. Over 2 1/2 miles of track laces the grounds and provides an excellent vantage point for viewing the zoo. A ride on the train costs 75 cents for adults and 35 cents for children.

At the opposite end of Nebraska is Riverside Park Zoo in Scottsbluff. At Riverside, Leo, a male African lion, is one of the main drawing cards. The zoo attracted over 100,000 visitors last year. Nearly every morning Leo announces his wake-up time not only to the head zoo keeper, but also to most of Scottsbluff as he sends a rumbling roar over the countryside.

Riverside Park Zoo was established in 1950, although some native animals were kept on the premises before. The zoo encompasses 15 acres and is operated 30

in conjunction with Riverside Park which spreads over

another 85 acres.

in conjunction with Riverside Park which spreads over

another 85 acres.

A "pet and touch" area is another strong point at Riverside. Children are able to pet braying donkeys, shaggy goats, guinea pigs, and woolly lambs.

It features exhibits native to Nebraska and also exotic species—leopards, mountain lions, Bengal tigers, black bears, mountain sheep, wolves, and a variety of monkeys. Hooved animals can also be seen there throughout the year without charge.

Situated in Lincoln is Children's Zoo, hailed as the largest "contact" zoo in the world. Last year some 155,000 visitors clicked the turnstiles at the zoo but, strangely, figures show that 60 percent of the visitors to Children's Zoo were adults and only 40 percent children.

Compactly laid out on 4 1/2 acres, Children's Zoo maintains an annual season spanning from Memorial Day to Labor Day. The facility opened its doors in 1966 and met with instant success. "Contact" with the animals is the zoo's best selling point. The entire philosophy of the facility is based on this people-to-animal contact.

Probably the biggest and most ferocious of the animals that visitors come in contact with at Children's Zoo is Leo the lion. Although Leo is constantly eating out of children's hands, he eats nothing but paper for he is not a real lion at all, just an electronic waste basket.

A new feature at the zoo this season will be a display called "Pick-Up-A-Chick". The exhibit focuses on the incubation and hatching of chicken eggs. Eggs will be placed in an incubator, which is equipped with a transparent glass side, through which the actual hatching of a chicken can be observed. After the baby birds emerge from the eggs, they will be placed in brooders, and after they are four days old, children will be allowed to "pick-up-a-chick."

Another new display at Children's Zoo this season is a number of exotic birds for Bird Island, including penguins and sandhill cranes. Goats, llamas, gibbons, otters, and wallabies are all favorites at the zoo. Charlie the talking crow, Bandit the raccoon, and Cappie and Brenda, two capybaras, the largest rodents in the world, are names that stay in the memories of visitors.

Railroad track surrounds Children's Zoo and those who ride the train have their appetites whetted before going inside. The train ride costs 15 cents. Included in future plans for Children's Zoo is a sea lion pool. If everything goes right, the pool will be under construction next fall.

Elsewhere in the capital city, only a short distance from Children's Zoo, is Antelope Park Zoo. There's little question that Skipper II is one of the main attractions there. A real showman, Skipper II is a chimpanzee who loves attention. His most famous act is roller skating about the park dressed in proper showman's attire. Following his roller skating act, Skipper II captains both a tricycle and pedal car.

A swan pond, aviary, and fountain garden are in the future for Antelope Park Zoo, which has just recently undergone extensive remodeling. It was established in 1935 and encompasses three acres. Exhibits at the zoo include chimpanzees, monkeys, a mountain lion, an ocelot, a ring-tailed cat, a kinkajou, reptiles, and numerous birds and fish. The zoo is open throughout the year and admission* is free.

Wildlife parks scattered throughout Nebraska play an important role in nature education and recreation.

32While they are, for the most part, devoid of exotic species, wildlife parks afford the opportunity for visitors to observe native wildlife closely and gain a stronger understanding ofwildlife. Cody Park at North Platte is just such an area. Alongside a general recreation park, the wildlife segment of Cody Park houses animals exclusively native to Nebraska. These include badgers, foxes, coyotes, pheasants, pigeons, eagles, raccoons, geese, ducks, a porcupine, and both mule and white-tailed deer.

Cody Park is more or less a "community thing" with North Platte. The park dates back to 1927. It stretches over 93 acres of land and includes 4 acres of lake. The park is open all year, free. During the JULY 1970 last year, estimated attendance was well over 50,000. Also incorporated into the park is a free campground.

Waterfowl seems to be one of the major attractions at Cody Park, according to a park official. Ducks, pre-dominately mallards, and geese, both greater and lesser Canadas, occupy the park's lake in large numbers, creating a waterfowl spectacle. On the drawing board for the park is a "pet and touch" facility which is tentatively laid out on 18 acres. No estimates can be made at this time about the projected completion date of this addition.

Pioneers Park in Lincoln devotes over 100 acres to a wildlife display. Visitors can see huge, shaggy buffalo roaming over the hillsides, a variety of deer, llamas, and much more. In total, 50 different types of animals roam Pioneers Park. Ducks and geese are plentiful in the lakes. Special feeding areas allow visitors to draw the waterfowl close to shore for a snack and close observation.

Another Nebraska area featuring observation of wildlife is the Fontenelle Forest Nature Center at Bellevue. A truly natural forest, Fontenelle is composed of 1,200 acres stretching along the Missouri River. Wildlife exhibits at Fontenelle include only those animals, birds, and reptiles that are native to the habitats at Fontenelle. The exhibits are unique in the field of animal keeping, in that the displays are "revolving". Some of the animals kept in captivity have been orphaned, wounded, or have met with other misfortunes. The specimens are kept until they are ready to go out into the forest again by themselves. Before the first customer is ready to leave, another of his kind has usually arrived to take his place.

Administrators of the nature center do not consider it to be a zoo, rather a natural environment for wildlife of the area. Many zoos pride themselves on the monetary value of their collections, but Fontenelle prides itself more on the educational value to visitors. Typical animals on display at Fontenelle are coyotes, foxes, raccoons, squirrels and opposums, along with birds of all types native to the region.

Forty-eight varieties of wild mammals live in the Fontenelle Forest, which in 1964 was designated one of the top seven Natural History Landmarks in the United States by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The beginnings of Fontenelle Forest date back to 1913.

Crystal Springs Park in Fairbury has been coined as a mini-zoo. The area is home for goats, turkeys, peacocks, bantams, ducks, and geese. Although Fairbury's mini-zoo is considerably smaller than other areas, all the meanings of zoo and wildlife park are still applicable. Crystal Springs is open all year without charge. Camping and picnicking are also popular there.

Tucked away in Norfolk's beautiful Ta-Ha-Zouka Park is a small zoo that features deer and bears. The zoo is open all year and admission is free.

Stolley Park in Grand Island was visited by some 130,000 people last year. The park sprawls over 43 acres and is administered by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. At the present time mule and white-tailed deer are the only animals there, but facilities for waterfowl are available.

All in all, big or small, NEBRASKAland's many zoos and wildlife parks offer the visitor a wide variety of education and entertainment. They promise a fun-filled approach to wildlife education that can only improve notes of discord between man and nature. THE END

33

MOMENT OF TRUTH

Now he's out of the water. Victory is only seconds away. I crouch down to reach for the walleye's gills

IT WAS A day that makes a man happy with the whole world. The sun was warm, the sky and water were blending their blues in mutual agreement, and I was at my favorite fishing spot, the rocky shore-line of Lake McConaughy. I didn't know it, but far below me a long and powerful fish was closing his jaws over my dancing doll fly. My greatest fishing thrill was about to begin.

The soft strike did not hint at the fish's size, and my first thought was that the lure had snagged on a rocky ledge. Suddenly, the "rock" moved. There was a strong, steady pull and then I knew that this was not just another fish. This was it —a dream coming true. This was the moment when an angler's rod bends downward with the nerve-shattering excitement and mystery of a possible record fish.

That morning had started like any other fishing morning. I tossed my fishing gear in the back of the station wagon scarcely dreaming that this July day would be unforgettable. True, I had often thought of someday catching that one fish which would long stand in the Nebraska records as the largest of its kind, but I wasn't expecting it to happen on that bright and golden morning.

My white doll fly provided a satisfying weight at the end of my line, but the action at my favorite fishing spot started slowly. I sat on a ledge and flipped the lure at various depths before beginning my retrieves. It was during one of these that I got the strike.

The line knifed slowly through the water from side to side, but its powerful pull told me to release the tension on the reel and let this fish run. My eight-pound-test line couldn't stand this pressure, so I had to let this fish wear himself out, for I didn't have the gear to stop his power. Helpless desperation crept over me, for I knew that if he kept going at his present speed he would soon reach the end of my hundred-yard line. Then the show would be over.

He stopped. The long retrieve began. Again, he turned to run and again I had to let him go, for this was the way the game had to be played. After 20 minutes my arms and shoulders began to ache with fatigue. Surely, he must be wearing out.

Thirty minutes passed and still I couldn't bring him in close and force him to the surface. The sweat ran off my forehead and into my eyes. My heart was pounding. I began to wonder if I had more fish than I could deal with.

Tension on the line eased and cautiously I began what was to be my final retrieve. I knew he was nearing the surface. The water began to boil and suddenly, 34 there he was. My doll fly was jutting from the jaw of the largest walleye I have seen in 20 years of fishing McConaughy. A new state record would be in the books if I could land him. I knew the record was a 16-pound, 1-ounce fish, but this walleye was over 36 inches long and would surely weigh more than that.

Now he was at my feet with victory only a few seconds away. I crouched and reached for his gills. At that instant he whipped his jaw to one side. Instead of grasping his gills my thumb was firmly clamped between his teeth. The fish had caught the fisherman! My blood was now mixed with his and the battle had taken on new dimensions. I couldn't get my thumb out unless I pried those jaws apart, so I put my rod down to use my other hand.

Grasping his upper jaw I began to pry the vise apart. With my hands on his jaws there was no way to lift him from the water except with the grip I had. My opponent had the advantage now, but there was no choice. A try for a new grip on his gills would be disastrous. Slowly, I started easing him from the water. He was now halfway out and I could feel his weight increase as he lost his buoyancy. Our battle was nearly over.

Then this beautiful, record-breaking specimen whipped violently upward and brought me upright out of my crouch. My hold was lost, and for a moment that seemed like an eternity, my fish was suspended in the air. The picture he made would return again and again in the sleepless nights that followed. I whirled and frantically grabbed my rod, hoping the lure was still attached. As soon as I picked it up I knew it was too late. The line had snapped.

Slowly, ever so slowly, the giant walleye returned to the depths. I could see the white lure sparkling in his jaw as he vanished.

I sat and dumbly stared at the sparkling water for a long time after that. Everything was just the same. The sun was still beating down on the rocks and the gulls still wheeled and dipped. Gradually, my perspective returned. The loss of the great walleye was not the end of the world. But I knew it would be a long, long time before I could forget the drama that had been acted on its stage. THE END

PHOTOGRAPHER'S CHOICE

A decade of memories lives again in the following collection of old pictures

EVERYONE LIKES TO look at old pictures. It's a pastime which brings back pleasant memories. This month NEBRASKAland presents a selection of previously published photographs which have appeared throughout the past decade. All choices were made by Lou Ell, photographic section chief, to represent what the magazine portrays in color each year, following the seasonal cycle from the birth of new life in spring, through summer and autumn, to the silence of death in winter. Included are pictures of activities related to each season, like fishing in spring or hunting in fall.

NEBRASKAland photographs have been consistent winners in annual photo competitions sponsored by the American Association for Conservation Information since 1964. Last year, when the competition became international, a series of black-and-white photos called Winter Song, published in February 1968, won first place. It was the fourth time an entry from this magazine came out on top.

A photographer's professional life is as interesting as life itself because this is the essence of what he tries to reproduce on film.

"One of the most difficult things is to make attractive what is usually considered to be commonplace," says Lou, a 57-year-old bachelor. 'You have to know about the little things in life to be able to capture the right mood in a photograph. You ask kids to play on a sandy beach, then you fade into the background and begin shooting after they have forgotten that you are there.

"As far as wildlife is concerned, you know it won't behave the way you'd like, so you sit patiently and wait for the right moment."

But professional photography is not all artistry. Sometimes there is real danger or humor involved. Take, for example, one winter when Lou was photographing a herd of elk at the Fort Niobrara Wildlife Refuge. He tells it this way:

"I was following the herd on foot as it kept moving away. None of the elk in the herd paid much attention to me, except one cow. Irritated by my presence, she pawed the ground and charged. I was too far from my car, so I dropped my gear, picked up a handful of snow, packed it into a snowball as quickly as possible, and let her have it right between the eyes.

"I let out a warwhoop and counter-charged, wondering if I'd be in the happy hunting grounds soon. My strategy worked. The cow stopped short, turned, and fled with the rest of the herd."

Other times he has fallen from trees while photographing birds' nests.

On one occasion he was walking through a rocky cliff area when he suddenly found himself in the middle of a rattlesnake den. They all started buzzing. "Needless to say, I beat a hasty retreat," he says.

Yet another time he was scouting locations for a panoramic shot of the Niobrara River. He was walking along the sandy, sloping rim of a 65-foot precipice when the sand gave way. He saved himself from sliding over the edge by grabbing a yucca plant which, he grins and says, "just happened to be growing there."

These are some of the more unusual incidents Lou likes to relate when he looks at his old NEBRASKAland pictures. He has been on staff nine years and took over as chief of the photo section in 1966.

Here then, are his choices, showing the colorful story of life in Nebraska. THE END

37

ME, THE VILLAIN

Our environment is smothering under a growing layer of trash. Everyone is to blame and only through a total drive to clean things up can we survive the plague

46 NEBRASKAlandLITTERING IS A FORM of vandalism. Few ever think of it as such, but it is the careless or willful i destruction or defacement of property—just like vandalism. Littering is an expensive crime. For tax-payers the cost of clean-up is astronomical.

How astronomical? In 1966, national, state, and local government agencies spent somewhere in the neighborhood of $419 million on refuse disposal. This included disposal of legitimate garbage, but litter was a substantial portion of the total. In Nebraska the roads department uses $166,000 for litter collection before accounting for the hidden costs. And hidden costs can add up too fast.

For the individual litterer the punch in the pocketbook can be tough. The minimum fine for littering is $25 plus cost. The maximum is $100-or $1000 for water pollution. In 1969 Safety Patrol and Game Commission officers made 271 arrests for littering. Fines totaled about $5,500 —not even 3 percent of the clean-up costs.

Not all convicted litterers are fined. Some are sent out for a grueling few hours picking up litter along a specified length of roadway. But that's not enough. Litter arrests have got to stop—stop after there's no more littering.

Summertime is litter time and Nebraska is no exception. The old adage, "little things hurt a lot," is all too true. Most frequent items found along the road-ways are disposable diapers, plastic rectangles that won't dissolve into the turf but lie on vegetation, eventually killing it. They are eyesores that clutter up the view.

Bottles and cans, an occasional broken table, a damaged canoe, lost cartop carriers, and stripped-down trailers, all get into the state's clean-up trucks. Studies show that motorists drop over 16,000 pieces of litter per mile each year on Nebraska highways.

A Lincoln fraternity used a roadside area to dump garbage —until the members were caught. Some persons take their household trash to a park area near town and dump it there.

Not everyone is a litterbug, of course. One state park manager congratulated Nebraskans, saying his worst offenders are raccoons that sneak onto the areas at night, pry the lids from trash cans, and rifle them for goodies. The people, he said, make every effort to be neat. If the trash cans fill up, they find bags and boxes to hold their trash and set them beside the park cans. Another manager said if the area is clean when people arrive, and if there are trash cans nearby, visitors usually leave the park as clean as they found it.

The only way to keep public or private areas clean is to make people stop littering. There are various suggestions to make them stop. One is education to let people know how much litter costs and how ugly it is. That's what we're trying to do here in NEBRASKAland Magazine. Another way is to raise fines and make controls more strict.

Another means of making people aware is through protest marching. But this can present a litter problem in itself. Take, for example, one anti-litter group which left 18 tons of extra trash on the streets of New York City at the end of its campaign.

Whatever the solution, the problem won't disappear until everyone realizes that he is the villain in the tragedy and decides to do something about it.

Of course you're not the bad guy. You know better than to throw a disposable diaper out of your car window. But last Saturday, weren't you driving along highway 281? You had been at a party and were finishing JULY 1970 that last beer. Well, of course, that's not littering. It's not even drunk driving. It's drinking and driving. It wouldn't be too good to have that beer can in the car though, would it? The "law" might not understand. But you didn't chuck that can out the window, did you?

The innocent green gum wrapper that blended so well with the grass has bleached in the weather now. It's just as white and ugly as everyone else's wrappers.

Some people—not you, of course —were picnicking at Two Rivers last Sunday. It was a busy day out there and all the trash barrels were full. Those people left all their picnic wastes from half-consumed hot dogs to blowing papers on the table.

The average family picnicker on a federal area leaves about a pound of garbage behind. Hopefully, he gets all or part of it into a trash can, and hopefully, a Nebraska outdoor-lover will be more careful of his local area. But if no one paid any attention to neatness, garbage would soon be knee-deep.

Only 500 families of 4 would pile up a ton of paper, bottles, cans, and left-over potato salad. Like a ton of feathers, the debris would spread across the recreation area. On a heavily used area like Two Rivers State Recreation Area, with 7,500 visitors on one warm Sunday, several tons of refuse could pile up.

The federal forest service estimates the cost of refuse collection and disposal at between $28 and $302 per ton. Assuming the low estimate, if every one of Nebraska's Wi million people had one picnic a season the resulting accumulation this year would cost about $13,500 precious tax dollars. But that's provided each person only went on one outing. Now, for a moment, think about the larger figure. One picnic per person would cost a total of $226,500 at $302 a ton.

Nebraska's costs probably range somewhere between the two estimates, but let's not forget that these estimated costs are only for picnicking. How much waste do we leave behind when we camp, or boat, or swim, or take a drive in the country, or see the sights, or ride our bicycles?

We go about our daily activities, now and then taking time out to gripe about taxes and high government spending. In the coming election we'll be looking for the man who'll spend the least the most wisely. But how about you? Are you making the effort to keep spending down?

Remember, you are the villain. THE END

47

MEMORIES IN WALNUT

With inspired imaginations, fires of adventure, Ecuadorians Reascos and Rodriguez begin their love affair with Nebraska

EDGAR AND CARLOS are wood-carvers. Although they are both in their 20's, neither was ever far from home until recently when they came to Nebraska. Their home is a small village nestled between the volcanic mountains of Ecuador. It is the sort of town that inspires the imagination and kindles the fires of adventure. Edgar Reascos and Carlos Rodriguez are bursting with both, but most of all they love to carve into wood what they feel and see.

Wood carving is neither their profession nor their hobby. It is their passion. When working on a walnut log they are able to release all the creativity, all the love or all the hate they feel inside. When Carlos is depressed he carves skeletons or suffering people. When Edgar is happy he carves beautiful women and laughing babies. Their talents are exceptional.

I have known Edgar and Carlos for years, having visited Ecuador on numerous trips. Last summer when I was in their town they came and asked me if I would help them.

"Take us along when you go back to the United States and Nebraska," Edgar said. "We want to know new lands and meet different people. We want new 48 feelings and new impressions so that we can continue to grow."

Carlos said, "We want to stay in Nebraska and carve what we feel. After some time has passed we want to display our work at an art exhibit. When we have realized that dream, we will return to our families."

Three weeks later the three of us were at the bus station in Grand Island and I called my wife to come and pick us up. Our ranch near Niobrara is about 160 miles north of Grand Island.

"I'll be right there," Arlene sighed when I told her that I had guests. "It'll probably take me two hours to get there."

I hung up the receiver and went to look for Carlos and Edgar. Neither speaks English. I found Edgar at a news rack looking at a magazine while Carlos, nearby, was trying to get a candy bar out of a vending machine. I explained that the penny he was repeatedly feeding into the slot wasn't big enough and told him to try a dime. He did and the candy bar tumbled out.

"That's strange," Carlos mused. "You say the red coin isn't enough, but when we try a smaller one NEBRASKAland

Carlos and Edgar are used to more mountainous countryside and serpentine highways than we encountered during our bus ride from Miami to Nebraska. At first they were pleased with the difference and long before we reached Grand Island they were bored. But they perked up considerably now as we drove in the family car along Nebraska's highway 14 as it began to roller coaster down toward the village of Verdigre, snuggled cozily in Knox County. Hillside and valley were parading their gaudiest colors and the seasonal changing of the guards was taking place.

Now each turn in the road triggered a pleasant outflow of Spanish. By the time we reached the windmill on top of a hill overlooking the Niobrara, Verdigre, and Missouri rivers, both men were completely intoxicated with the festival of fall. I parked the car at the crest of the hill. Both Edgar and Carlos tumbled out to feel the scarlet sumac leaves, finger the sharpness of yucca spears, and draw in deep lungfuls of air. Edgar has an unusually sensitive eye, and to him, balance JULY 1970 plays an essential role in determining whether something is visually pleasing or displeasing. A large towering mountain disturbs him; huge bodies of water and large rivers make him nervous.

In his opinion, The Creator did a lousy job of throwing our planet together. "Scenery seldom pleases me," he says, "because nature has allowed the land to dominate the water as she does in the mountains, or she has allowed the water to dominate the land as she does with oceans, large lakes, and rivers."

But I could see now, as Edgar ran his eyes over the hills, valleys, and rivers, that he was pleased with what he saw.

"This is indeed a very rare beauty that you have in Nebraska," he said. "Here the land and water compliment one another and neither battles the other for superiority. The water does not detract from the beauty of the land, nor does the land detract from the beauty of the rivers."

Edgar and Carlos had brought their wood chisels

and as soon as they became familiar with their new

home on our 1,200-acre ranch, they asked me to help

49

At the Bill Mayberry ranch we found two large logs that had been cut and cured for five years. Bill fired up his steam-powered sawmill and ripped the logs into three-inch planks.

Later we obtained several huge walnut trees from the John Prouty ranch near Spencer. John wouldn't take any money for the trees and his generosity baffled the two South Americans, as did many other things they saw in Nebraska.

They had never heard of highway speed limits and wondered why I stopped at intersections when there wasn't another car in sight. "In Ecuador," Carlos beamed, "the faster you drive, the better a man you are." Laughingly, he says American drivers are a bunch of sissies.

Carlos was thrilled when he saw the Niobrara Lions on the football field. He sees American football as more brutal but still more masculine than the soccer he plays in Ecuador. Carlos decided that his first Nebraskan 50 sculpture would be a tribute to this great American sport. He spent his first month carving a tangle of helmets, cleats, and shoulder pads on a six-foot walnut plank. But Carlos is also a gentle man. His next two sculptures were dedicated to the theme of love —the love one has for his fellow man, and the love it takes to help a newborn infant draw its first breath of life.

Edgar is more obsessed with finding the differences in things, and accentuates them in a satirical way that makes you even more aware of the universal similarities that motivate men.

When he saw Nebraska hunters prowling the cornfields for pheasant and wading the swamps for waterfowl, he decided to carve "The Hunter" in walnut. Within a week his sculpture was complete. He showed it to me and I thought it was good.

"The Hunter" is a huge man cloaked in a thick, sleeveless parka. He stands amid a pile of dead birds. With muscles bulging on his massive arms, his three-fingered NEBRASKAland

I recognized the face immediately. It was of Frank Sherman, a friendly hermit with a heavy-set jaw who lives along the Missouri River in a tar-paper shack not far from Niobrara. Frank has a lot of hard winters etched into his face and Edgar considered it to be "the most beautiful face I have seen" after he met him the first time.

It shocked me when Edgar carved the figure of a pregnant nun. At first I thought it to be vulgar. But then I realized that this was just Edgar's way of saying that the rules which society imposes upon the individual cannot extinguish the feelings one suppresses.

Edgar's working hours had no pattern. A particularly stimulating sculpture could keep him chained to his work for days and nights without meals or rest. Other times he sat wordless staring into space. When he dressed up and walked to Niobrara we never knew if he would be gone for an hour or a week.

Edgar is the first to admit that his self-discipline is virtually nil. "I don't want to think with my mind, I just want to think with my heart," he said to me one evening. "If I think with my mind a computer can replace me, but if I think with my heart nothing can replace me."

Sometimes Edgar carved and sometimes he painted, or molded clay. After eating a melon, he Edgar Reascos has a very sensitive eye. To him, balance is essential to beauty sometimes rearranged the seeds in his plate to spell out "thank you".