NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

June 1970 50 cents BOB GIBSON Nebraska's own is carving a niche as a basebal great WILD FLOWERS Tiny Spartans of spring storm gates of winter's realm

WHERE THE SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

A Family Affair

For family fun, NEBRASKAland's great outdoors is the place to be. There's no generation gap on the shores of a sparkling lake or rushing stream. There, everyone speaks the same language-the language of Nature. There's nothing quite like the aroma of fresh fish sizzling in the pan over an open fire to draw folks together. Mom, Pop, Sis, and Brother can all get hooked on the family affair of fishing. To make the excursion more productive, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has published a free brochure, "Where the Fish Are". For your copy write to NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, 68509. And, your friendly, neighborhood permit vendor has the tickets for months of pleasure. Remember, the family that fishes together, grows together.For the Record ... QUALITY OF LIFE

Tomorrow is the first day of the rest of your life! What you make of it and the world you live in is up to YOU. You and I can work individually or together to make it a better place, or we can turn our backs and ignore the problems that face us. But, the Earth is a closed ecosystem. If we despoil it, there is nowhere left to turn.

Wildlife is a most reliable barometer of the conditions facing all forms of life. We all know about extinct species. When their habitat (environment) is gone, they are doomed.

One of the oldest definitions of conservation is "use without waste". When we have USED our rivers and lands to the point where they no longer support life, we have wasted them.

Sediment is one of our most serious forms of pollution. It can be checked if the land is put to proper use... a use that will also support wildlife in greater numbers than now. Still, there is hope of changing the land use, so it will increase production of all forms of wildlife.

There are many kinds of pollution. One we "hear" little about, but that should vitally concern us, might be labeled "environmental intrusion" — NOISE.

As the director of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, I pledge my personal and my department's support in the cause of preserving our environment. I feel it is particularly significant that my term began on Earth Day, the greatest single demonstration of concern for our world ever seen.

The Game and Parks Commission further will work diligently with all levels of government to actively represent the wildlife and outdoor recreation interests of all Nebraskans. That includes such groups as the Governor's Planning Commission, the Soil and Water Conservation Commission, the Department of Agriculture, and various branches of the University of Nebraska.

We further pledge to:- continue to develop tourism programs that will revitalize rural Nebraska and merchandise our fascinating history;

- direct our resources toward early and complete development of major state park and recreation area facilities;

- continue efforts to preserve our wetlands to increase the production of migratory waterfowl;

- strive to further a "Code of Outdoor Ethics" that will promote respect for the rights of all and limit harvests to one's fair share —in other words, to behave like a true sportsman".

If we are going to enjoy the "Quality of Life", then we must begin now to preserve the lands and waters and to bring back, if possible, those that have already been despoiled. This, then, is the challenge.

Yes, tomorrow is the first day of the rest of your life. What you make of it is up to you... and me.

WILLARD BARBEE Director, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission JUNE 1970A Cooper HORSE FEED FOR EVERY NEED

Cooper COMPLETE HORSE PELLETS A completely balanced ration that furnishes everything other than water and free choice block salt. Cooper Complete Horse Pellets provide required amounts of vitamins and protein as well as minerals, and trace minerals. Cooper SPECIAL HORSE CONCENTRATE Formulated to be fed by horsemen who have adequate roughage to feed along with the grain concentrate Mix. Like Cooper Complete Pellets, Special Concentrate contains necessary added vitamins, proteins and minerals. Cooper 24% HORSE SUPPLEMENT BLOCK Not just a protein block, but chock full of vitamins and minerals for healthier animals. Minerals help build bone formation and structure, while vitamins help maintain animals in good condition.

Sunny Side Up!

...new Snyder Sheik Dune Buggy Bodies After producing over 4,000 fiber glass automotive bodies you become an expert. Now, Snyder's have their own quality "better-built" dune bodies available in all popular colors and in metal flake, too. The Snyder Sheik has recessed headlights, improved dash panel and widefenders.TRAVEL TIP OF THE MONTH

For the "best of the West" and the time of your life, take in NEBRASKAland Days at North Platte. Western parades, exciting Buffalo Bill rodeo, pretty gals, and real chuck-wagon chow make an action-packed weekSpeak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.YOU'RE WRONG-"My father, the late H. M. Springer of Antelope County, owned the pastureland where the landslide (A Lake Is Born, December 1969) occurred. He owned it from 1910 until 1931 when it passed down to his children, then to a grandson until it was sold to Mr. Vanderheiden of Elgin in 1958 or 1959. Mr. Vanderheiden owned the Elwood farm mentioned in your article and it adjoined the Springer land on the west. He wanted the land to make a lake which was made by building a dam downstream on the Springer land, thus the large lake was man-made — not born.

"The landslide started about 1926 and was very gradual, starting with a crack in the ground which kept getting bigger and settling more and more. Then another crack would appear. It all happened very gradually, so there was never a chance that a span of mules could have been buried in it.

"Another mistake was that there never were milk cows driven over the hill because it would have been impossible to get them over there. There never was much conversation in the store about the landslide as an outsider couldn't get in to see it. There was no public road past it and you had to go across several farms belonging to different people, which made it almost impossible to get to it.

"The water in that stream was crystal clear and real cold. There were springs all along the stream which flowed the entire length of the pasture which was one mile long. The millstream pond at NEBRASKAland Oakdale was mentioned as filling with the silt from the landslide, but it (was already) filled and wasn't used some years before the landslide started." — H. S. (Hobart) Springer, Exeter.

PIONEER COOKIES-"I thought some of your readers might be interested in this recipe for pioneer cookies. It has been changed somewhat to take advantage of modern ingredients. For example, the recipe used to call for bear cracklings, but pork has been substituted.

Pioneer Cookies 2 cups pork cracklings 1 teaspoon salt 2 tablespoons dark syrup 1 cup sugar 1 teaspoon soda 2 tablespoons corn oil 2 eggs 1 cup brown sugar 1 teaspoon 1 teaspoon vanilla cinnamon 1 teaspoon vinegar 3 cups flour

"Mix all ingredients, drop onto cookie tin and flatten with fork. Bake for 10 or 12 minutes in a 400-degree oven. Will yield about 80 cookies." —Mrs. Lester Dannehl, Bertrand.

WHITE-WINGED SCOTERS - "Robert Reager and sons were hunting on the Platte River east of the Chapman bridge. They killed two ducks that they did not know and stopped at my home to see if I could tell what they were.

"I was quite sure I knew what they were as Francis Larson (now dead) and I had killed three in 1946 or '47, about four miles east of Central City off of Prairie Island, that looked like the same kind of ducks. I have three books which show that the ducks were white-winged scoters.

"I have hunted in the Platte River since 1907 and have never heard of anyone ever killing any of these ducks. There were eight in the flock that Larson and I saw and Mr. Reager stated there were five in their flock.

"They fly very, very fast, do not decoy but swing across the decoys and straight ahead 10 or 12 feet above the water, very similar to the flight of redheads." — Ernest Beaty, Central City.

SOCK IT TO 'EM-"I am 14 years old and enjoy your page in NEBRASKAland about 'Outdoor Elsewhere'. I have a hint that I figured out to keep my hunting dog trained. My Lab retriever is good at bringing in fowl from the water, but I needed something to throw into the water for him to bring back for practice that would not sink. So I took three rubber balls and a heavy work sock, put the balls in the sock one at a time, and packed each with straw to make it firm. I tied the sock tightly so it was good and strong and would take a lot of use." — Chuck Smedra, Loup City.

SMALL TOWN STORIES-"I have, for many years, enjoyed looking at your magazine and this year I finally have a JUNE 1970 subscription for it. Your section entitled 'Speak Up' gave me the idea of writing. Since you welcome suggestions, I will offer one.

"Many of the readers from around the state live in small towns which they feel could be talked about a little more. So, why not have an article, possibly each month, on a place which a reader has asked about. The article could include present-day facts about the place, its history, its importance, and what it is known for. You could even tell its population, date of incorporation, etc. Many people will look forward to seeing their selections printed in NEBRASKAland." — Bill Noel, Lincoln.

YOUNG MASTER-"Our 10-year-old son, Jerry, recently took a 12-pound, 4-ounce walleye at Lake McConaughy, which so far has netted him several angling awards, and put him in line for more.

"Jerry received the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission's Master Angler Award, a Distinguished Angler's Award and a Best in Species Award from Sports Afield magazine, and a Certificate of Award and an Honor Badge from Field and Stream magazine. He also placed

OVER THE LINE-"I sure would like to take a spin around NEBRASKAland, but not on a bus that goes around a curve on the yellow line (Inside Front Cover, April 1970) "-Carl Grotrian, Cook.

Safety standards are, of course, among our major concerns at NEBRASKAland. The photograph Mr. Grotrian referred to was set up for impact and technical excellence. And, the photographer took all necessary precautions to assure the safety of all concerned. — Editor

NEVER AGAIN-"In the days before the railroad, my grandfather Dierks lived on a farm near Johnson. He had five sons, so when the crops were harvested, he started them out with a wagon train of freight for Denver.

"At that time Kearney was located on the Platte River and freighters were never bothered by the Indians before they reached the community. Once there, the boys would circle the wagons and stand guard. The Indians would come in, ride around the wagons until the freighters fired a couple of shots in the air, then the tribesmen would depart.

"On the trip west, they came to a place where the Indians had attacked some white people. Quite a bit of stuff was strewn around and the boys found a stove with a built-in oven. They took it all the way to Denver and brought it back for their mother. The boys bought merchandise in Denver and sold it in Kearney when they returned. They bought grain with that money and started for Denver again making about 12 miles a day.

"They were late in getting home and grandfather began to worry. He told grandmother he thought the Indians had gotten them. But this is what had happened.

"One of the boys got rheumatism in his feet and couldn't walk. He sat at the edge of the Platte River and soaked his feet all night in the ice-cold water. He never had rheumatism again.

"My worried grandfather would take his binoculars and peer west. Then one morning, he saw his sons coming. He ran into the house yelling, They're coming! They're coming! They will never go again!'" —D. A. Wolf, Lexington.

NO ESCAPE-"In 1921, my aunt and uncle left Nebraska for Burbank, California, and my aunt cannot forget one feature of our glorious Nebraska that offers little relief for an asthmatic condition. She writes with some nostalgia." — Cecil Eloe, Lincoln

ODE TO THE GOLDENROD by Mrs. Angie Fitzsimmons Back in Nebraska grows a posy It's not fragrant, It's not rosy. Its pollen makes me sneeze and weep When I'm awake or when I'm asleep. So, to avoid this'gorgeous pest I packed my grip and came out west, Where I can cough and weep like sin Each day the dirty smog comes in.PROPAGANDA —"I have just finished reading your article, The Platte River Dam, in the March issue of NEBRASKAland.

"Frankly, to me this has all the marks of a purely propaganda piece for the Game and Parks Commission. I do agree with all your conclusions as to the need for more and better recreation, etc. But, I can't agree with some of your statements that Nebraskans are especially recreation conscious, or that the Platte River project, as planned, would fill the need.

"The proposal for the dam and lake has such little overall merit, in my opinion, I am surprised the Corps of Engineers advanced it. One explanation might be (Continued on page 13)

7

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . COMMON TREEFROG

Aptly named, this diminutive amphibian spends most of his life in trees. Once a gilled polliwog, the adult gains lungs and starts to climb

MANY A NEBRASKA bird-watching enthusiast may beam with excitement on hearing a strange new call in a nearby bush. But, to the amazement of an equal number when the source of the call is pinpointed, it is not a feathery friend at all, but the Hyla versicolor, more familiarly referred to as the common treefrog.

Aptly named, the common treefrog spends most of its life in small trees or shrubs in or near shallow water. He can also be found along fences and on vines. Tree-climbing ability comes from adhesive discs on the tips of the frog's digits. Males are seldom found on the ground, except during the breeding season. Prior to that time, they may remain landlocked for periods ranging up to 10 days. During winter, treefrogs, like others of their species, burrow into the mud, soil, and muck under the water to hibernate. This practice limits their range, however, since they are unable to survive in climates where subsoil is permanently frozen.

The common treefrog is the only species of treefrog found in the north. Its range extends from northern Florida, north to Canada, west to North Dakota, and south to central Texas. In Nebraska, the species is 8 found in the eastern part of the state and is relatively common along the Missouri River. Recorded sightings in Nebraska have occurred at Omaha in Douglas County; one-half mile east of Sprague, at Lincoln, and at Roca in Lancaster County; at Peru in Nemaha County, and south of Rulo in Richardson County. While many of their cousins live considerably longer, treefrogs generally reach the age of nine years. Ranging from IV4 inches to 2lA inches in length, the treefrog has webbing between its toes that extends to the terminal suction discs used for tree climbing.

Common treefrogs are relatively easy to identify, when they are found. Although the skin on the back is quite warty for a treefrog, the warts are not as prominent nor do they protrude as much as those of the common toad. Their skin is also quite tough and the head is short and broad. There is a wide variation of color in this amphibian, running the gamut from gray, brown, or green to pearl gray or even white. A dark blotch on the back and a light spot under the eye is nearly always discernible, with the concealed undersides of the hind legs sporting a bright orange hue with wavy brown stripes in males. Unlike others of its species, the common treefrog never has stripes on its back.

Like the chameleon lizard sold in pet shops and seen in circuses, the common treefrog has a camouflage technique of blending with its background to avoid enemies. It can render itself nearly invisible when clinging to brown or gray tree bark and is capable of changing color rapidly. Often, the only way its presence can be noted is by its vibrant call, a loud, resonant trill, lasting 1 to 3 seconds and repeated every 10 to 20 seconds.

Though the frog is primarily nocturnal, its call can occasionally be heard during the day when the weather is damp and cloudy. The call, often disconcerting to those in the immediate vicinity, is usually sounded as the sun lowers over the horizon and evening comes on.

Mating season normally begins in April and runs through August, depending on rainfall and temperatures. However, this hopper does not call or mate when the temperature dips below 50 degrees fahrenheit. During the mating season, treefrogs often congregate in considerable numbers and croaking may continue into the late evening during such a gathering.

The mating embrace takes place in open, shallow water, though bushy areas are nearby. Egg masses containing 5 to 40 eggs are laid, with a single female capable of laying up to 1,800 eggs. The bouyant eggs are attached to the vegetation at the waterline, and begin to hatch in four to five days. Early stages of the treefrog are tadpoles or polywogs. Unlike their later frog form, tadpoles are usually vegetarians and are identifiable by red and black markings on their tails. After hatching, they look remotely like big-headed fish without fins. They breathe with gills, have a tail, and are equipped with a special mouth and a long intestine adapted for their vegetarian diets. Within 90 to 100 days, they begin the transformation into tiny frogs. They develop lungs in place of gills, four limbs appear, the tail is absorbed, the intestine shortens, and the typical frog mouth becomes apparent. As the conversion continues, the small frogs spend less and less of their time submerged, venturing farther onto land.

From the tadpole stage on, treefrogs feed on nonaquatic insects such as bugs, flies, and beetles. These tiny members of the amphibian world add a bit of spice to NEBRASKAland outdoors. THE END

NEBRASKAland

SINKING SAND

SUMMER SUNDAYS ALWAYS had a special appeal to me. They were for pure relaxation. They meant freedom from worldly cares and a chance to refresh myself before the next week's work.

One particular summer Sunday, however, holds special meaning for me. That particular Sunday, in August 1940, found me 19 years old. In less than three years, I would be a pilot in the Southwest Pacific with the United States Navy. That Sunday meant much to me —in many ways.

My favorite Sunday pastime was fishing. I had been going with a buddy each weekend, but this time he couldn't make it. I did get to use his car though, a 1929 Model A Ford. So I planned to head for a good spot a short distance from Grand Island, where I was living at the time. Friends had told me about their good luck at a sandpit, and gave me directions to it.

Saturday I took care of the preliminaries so I would be all set to go as early as possible the next morning. I picked up some minnows and worms and, because the weather had been quite warm, I set up a sprinkler to keep them alive over-night. My gear was ready to go and I was anxious to angle.

That night was nearly as warm as the day. It felt good to get up at 4 a.m. and enjoy the quiet peacefulness of early morning. I grabbed my gear and headed for the sandpit, not far from the Platte River south of town. When I arrived it was just starting to get light. But even at that hour it was already getting warm. It would be a hot day.

The sandpit was not very large, about 100 feet across. I walked to the edge through deep, soft, pure white sand, getting a load of it in my low-cut tennis shoes with each step. Across the way stood the dredge that, during the week, had been working to enlarge the hole. A long strip of sand tailings, the discards of a gravel operation, ran from either side of the machine.

I didn't look long at my surroundings, however, for fishing was on my mind. I was mostly interested in bass, my favorites, but I would take what I could get. Using worms, I began working rather deep. My first fish that day was a bluegill, and within a short time, I pulled in several crappie. There was no wind, and the water was absolutely flat. I had begun working my way around the pit in a clockwise direction, when I noticed ripples on the other side NEBRASKAland

That was all the invitation I needed. Walking to where the action was, I changed my tactics, taking off the weights, putting on a minnow, and working the surface. I was soon rewarded with a nice largemouth, about a pound and a half. Moving closer to the dredge, I came up with two more, including a three-pound beauty. By 8 a.m. I had a pretty heavy stringer with more than a half dozen fish. It was getting hot, so I knew that I wouldn't be staying out much longer.

I had moved around to within 25 yards of the dredge and was standing at the edge of one of the sandy beaches. My gear was right with me, tackle box, minnow pail, can of worms, and that loaded stringer. I was still working on those bass, hoping to land a few more before leaving.

From behind me came a muffled cracking sound. At first I paid no attention, but the sound continued, becoming louder and louder. I turned around and was amazed to see what was happening. The sand on which I was standing was slowly sliding away from solid ground 30 or so feet away. Sensing the peril I was facing, I dropped my rod and abandoned my gear. I began to run as fast as I could.

The crescendo of noise continued. As I ran, the earth beneath me was JUNE 1970 falling. Foot by foot, the sand slowly slumped from the bank. It took me only seconds to cover the 10 or 15 yards to the break-off, but already the firm ground was at shoulder height. I scrambled up and slid over the top. I turned just as the entire area where I had been fishing completely caved in.

Squatting at the edge, I waited for the finale. As the sand sank, water from the pit poured over it. As if in a huge kettle, the water began to boil. Bubbling and hissing, it churned and swirled. A vast cloud of dust formed over the entire area. Sand filled the air as in an explosion.

For nearly a half hour I sat there, watching the dust slowly settle and move away. The air was absolutely still and the sun bore down on me as I pondered what had happened. Had I not made that sudden move, I would probably have been drawn under by the sudden suction of sand and water, and been with my gear somewhere at the bottom of the pit.

I lost a few things that day, but I gained a lot more. My brand new flyrod was gone, as well as the rest of my tackle. But in their place I had gained some maturity and wisdom. I would value life a little more in the years ahead. Every once in a while I think about that hot summer day in 1940 and get a little bit of a "sinking" feeling. THE END

WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to- Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM 11

Peru State College

JUST A FEW months after Nebraska became a state, Peru State College, then called the Nebraska State Normal School, opened its doors as Nebraska's first state-supported college. To honor the state's oldest institution of higher education, a State Historical Marker has been erected on the campus by the Historical Land Mark Council, since absorbed by the State Historical Society.

Nestled in the gently-rolling, oak-studded hills of Nemaha County on the outskirts of Peru, the cornerstone for the college was laid in the spring of 1866. It was a combination Methodist church and school, christened as Mount Vernon Seminary. The building was only partially completed when the college opened for business, and its one-man faculty, J. M. McKenzie, greeted 36 students.

Soon, however, the church and local residents, who had contributed to the college, clashed on how the school should be operated. McKenzie foresaw the fall of the neophyte college and decided to try for the establishment of a normal school, supported by the state when statehood came.

McKenzie's premonition proved correct and his efforts, combined with those of the newly-elected Nemaha County legislators, won out. The first State Legislature authorized the location, establishment, and endowment of a State Normal School.

During the first year, McKenzie and his wife were the only instructors, with an enrollment of 71. The next fall the faculty was increased 50 percent with the addition of an art and music teacher.

In November 1870, McKenzie was elected State Superintendent of Public Instruction and left Peru State. However, a firm foundation built during his four years of leadership awaited his successor.

During its first 100 years the school had 4 official names. It kept its original name of Nebraska State Normal School until 1921 when authorization from the legislature granted bachelor's degrees in education and a change from a two-year to a four-year curriculum. The school then became Peru State Teachers College. In 1949, the granting of the liberal arts degree brought along with it the name Nebraska State Teachers College at Peru. The last change came in 1963 when a drive for individuality and a recognition of common usage changed the name to Peru State College.

A dormitory and glass-walled student center now share the site of the original Mount Vernon Hall. The once fledgling campus now stretches over a hundred acres dotted with 20 modern-day academic structures, and a thousand stately oak trees. The 1969 enrollment reached 1,263. The college looks to the future with dedication and determination characterized by its past in serving Nebraska.

JUNE 1970SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 7)that, at present, they have just about run out of projects — and necessity is the mother of invention. In short, they need something to keep going on and to justify the setup they have in Omaha.

"The estimated cost of $495 million would undoubtedly represent a final cost of three-fourths of a billion dollars. The engineers never built anything in their lives that did not run way over the original estimate. As you say, this would be a lot of lake, but this also is a lot of money. This would probably be 90 percent boating as far as recreation is concerned. I can't, for many reasons, see it as much of a fishing lake. Most projects have other values to justify most of the cost. As I understand it, electric power or irrigation do not enter the picture. Solely as a flood-control project, smaller dams on tributaries would be more practical at a fraction of the cost." — Emil F. Leypoldt, Lincoln.

This article was written before concrete plans for building the Platte River Dam were approved. The Corps of Engineers has since laid these plans aside to further study a proposal that dams be built on Platte River tributaries farther upstream. -Editor.

MORE ON THE 1733-"I read the Speak Up about the 1733 Ranch near Kearney in NEBRASKAland last June. There was a sign there at one time, but I haven't seen it in recent years. Here is a picture

See story on 1733 in July issue.— Editor

CREELING A "STIRK"-"This incident occurred some 40 years ago when my father and a friend, named Bill, were fishing the Cumberland Derwent near Isel in northwestern England.

"After reaching the river, the two agreed that dad would fish the first pool while Bill went through the gate to the next field. There was a herd of young stirks* grazing in dad's field and they could see only part of dad.

"The beasts were puzzled to know what on earth was going on as dad kept raising his arm to make the casts. Curiosity got the better of them until one got too close and was hooked in the tail by dad's back cast. As soon as it felt the prick of the hook it took off like a streak of lightning.

"Bill couldn't see what was going on, but he heard the reel screeching as the

"Imagine his surprise when he got to the gate and saw dad in midfield, his rod held high, chasing the stirk. Between them they got the beast cornered.

"Whenever the two men get together and talk over the good old days, the incident is sure to come up."—Miss A. E. Moore, Blennerhasset, Carlisle, Cumberland, England.

*Stirk is "British" for steer. — Editor

NEBRASKA ODE by Mignon A. Greenwood Brush, Colorado Oh State of Nebraska, Where buffalo have roamed, Once known as a prairie The Indians called home. Then came the white settler To farm the rich land Build railroads and cities Forever to stand. Oh State of Nebraska What secrets you hold. Of hardships and struggles Of pioneers bold. Their dream for the future 'That when they were old A state would be thriving A prize to behold' Oh State of Nebraska Our Queen and our King. From Spring on through Winter Your praises we sing. From schools and from churches Your name ever ring, And ever we'll labor Your laurels to bring. You're a star in Old Glory Forever to shine And light up your part Of the blue so divine. We gather so gladly Our strength to combine, And stand, Oh Nebraska As true sons of thine. 13

ELECTRIC FILLETING

Here's a better, simpler way to clean fish—and without the mess

RARE IS THE fisherman who doesn't enjoy a day afield, whether it be on lake, pond, or stream. Equally rare is the man who, upon returning home, thoroughly enjoys cleaning a mess of fish. A few lucky souls can delegate such cleaning duties to a well-trained spouse or offspring. But, most anglers resign themselves to the task. And, completion of the chore usually finds them scale-covered and muttering something about "a better way".

There is a better way —filleting. Often considered a difficult process to learn, known only to professional fishing guides, the procedure actually is relatively simple and can be mastered by anyone.

To fillet means simply to cut the strip of meat off both sides of a fish, leaving bones, innards, and skin intact, to be discarded. This eliminates the necessity of scaling and gutting, plus cutting time and mess to a minimum. The filleting knife, with its long, thin, flexible blade, has long been part of the serious fisherman's gear. However, the new electric knife makes the cleaning process easier yet.

Filleting may be done on any clean, flat surface. Begin by making a cut from the back to the belly, directly behind the pectoral fin. Depth of cut will vary with the size of the fish. Cut to the backbone, but not through it. Just before reaching the backbone, ease the knife into a horizontal position and continue cutting toward the tail, still using caution not to cut through the backbone. Stop cutting just before reaching the tail. The fleshy side of the fish will now be free, with the exception of the flap of skin holding it at the tail. Flip the fillet over, meat-side up, and insert the knife between the skin and flesh. Work the knife along between the meat and the skin until the meat is completely free. The result is a fillet containing only a few rib bones which can be easily trimmed out. Cleaning is completed by repeating the process on the other side of the fish.

The first few attempts may result in thin fillets with considerable meat left on the bones and skin. However, with practice, little meat will be wasted. After a couple of trial runs, cleaning a pan-size fish can be completed in less than a minute with minimum mess. The boneless fillets may be either pan-fried or cut into strips, dipped in pancake batter, and deep-fat fried. Either way, you'll find any fish more welcome at the table without any bones. THE END

NEBRASKAland

God blessed America.

He gave it a beautiful face. Majestic purple mountains. Shimmering ice-blue lakes. Crisp, clean airto cool the deserts and waft across magnificent canyons. Rolling, fertile plains .. . alive with colors that must be seen to be believed. All stretching across 16 states . .. from Memphis, to Las Vegas . .. and the Canadian border to the Rio Grande. This is Frontierland, where it's still America the Beautiful. To make sure it stays that way, many areas of Frontierland are protected as national parks. Like Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Grand Canyon National Park. Come and see for yourself. And count your blessings.THE CHANGING FACE OF CONSERVATION

Compromise has sold down the river pure water, clean air, and wild creatures, threatening the quality of existence

I AM an angry man! I've had 25 years to build a full head of steam. I detest the word "compromise" with a passion. We've used the word as a vehicle to sell wildlife down the river.

Tell me, how do we compromise pure water, clean air and wild creatures?

I am impatient! Impatient with conservation lip service, impatient with the attitude, "Let's wait till next year," and impatient with laws that provide the authority but no teeth or funds.

I am irritated. Irritated with just plain people who stand to gain or lose the most.

We have a problem. Take a look!

Oklahoma is losing 100,000-plus bob white quail each year and South Dakota is trying desperately to shore up a sagging pheasant population. In Saskatchewan and the north-central states, the ability of the prairie marshes to produce ducks decreases about 80,000 birds each year.

In Wyoming and Montana, antelope show a precarious trend and may be living on borrowed time. South Dakota's pheasant population once numbered a whopping thirteen million birds and today, about three million.

Pesticides, herbicides, bulldozers, plowshares, drainage ditches, reservoirs and even such things as woven wire fences are playing havoc upon our wild environments.

Some of the best saltwater ecologists in the country tell us the Mississippi River drains the chemically polluted waters of thousands of tributaries into the gulf. Here many of the more stable chemical compounds threaten to (Continued on page 52)

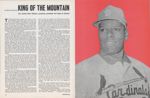

KING OF THE MOUNTAIN

For hurler Bob Gibson, practice, prowess are keys to throne

TO THE MILLIONS of people who throng to baseball stadiums across the nation each year, the knoll in the middle of the diamond is simply the pitcher's mound. To Omaha's Bob Gibson, right-handed hurler for the St. Louis Cardinals, it is a mountain. And. he has taken up at least semi-permanent residence as king of that mountain. With each roar of the crowd and wink of scoreboard lights, Gibson entrenches himself that much deeper as an absolute monarch in a domain he knows best —baseball.

Things have not always been so bright for Gibson, however. What promised to be little more than a mediocre life began for Bob on November 9, 1935, in what he calls the ghetto of Nebraska's first city — Omaha's North Side. Bob never knew his father, Pack, a mill worker who died of pneumonia a month before the boy was born. But he did know his six brothers and sisters, one of whom was to have a profound and guiding influence on his life in sports. Things were tight. Victoria Gibson, Bob's mother, spent long hours working in a laundry to provide a life for herself and her children. But, at best, poverty was the name of the first game he played. Bob recalls wearing a hand-me-down coat for three or four years, until there were too many holes in it to patch anymore. And, he remembers that when he wore holes in his shoes, he'd stuff in cardboard to keep water from seeping through when it rained.

Things were bad, true, but poverty may have been the making of Bob Gibson. He recalls not having enough money for many of the diversions other kids had. So, he and his playmates had to resort to the amusement they found in sports, the kind they could play in the street or on neighborhood playgrounds. Baseball and basketball were at the head of the list. Gibson remembers playing baseball from the time he got up in the morning until he went to bed at night. Practice makes perfect, or so they say. And even at that early age, Bob was on his way, though he may not have known it at the time.

That he was working up to something became apparent a few years later when his brother Josh went to work for the YMCA in Omaha. Fifteen years Bob's senior, Josh worked with the kids in the Y, teaching them the baseball fundamentals he had known for years. The person he worked with most was Bob. Gibson remembered that his brother seemed to push him much harder than he did the other kids. In fact, he still carries a scar over his left eye which he picked up when a brother-batted ball took a bad hop and caught him in the head. Still, young Gibson couldn't stay away, going back for more and more work, probably realizing that the technique he was learning by heart would pay off later —in cold, hard cash.

High school days at Omaha's Technical High were a bit of a surprise for Bob, however. Sure of his athletic talents, he tried out for the football team only to be rejected because the coach said he was too small. Still 18 short of 5 feet, he weighed in at only 90 pounds. Bitterness and disappointment were natural for a kid that age, but there was solace in the fact that his favorite games, baseball and basketball, were still ahead. Irony struck again, however, when he showed up a day late for baseball tryouts in his junior year. Gibson remembers the coach running him out of the fieldhouse, telling him to join the YMCA team if he wanted to play ball. That was mistake No. 1.

Josh Gibson coached the Y team and Bob remembers that when they reached the city championships that year his team beat the pants off another, coached by that same high school coach.

But time was running out in high school. He rejected an offer to play semi-professional ball for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro league. It was time to start looking for a college to attend. With plenty of ability in both baseball and basketball, but little or no money, Bob sat back to wait for athletic scholarships to pour in. They didn't. Instead, he just managed to snag a scholarship at Creighton University in Omaha on the last go-around. His was a basketball ride, and Gibson admits to having the impression all he had to do was play ball, and do it well, to get through school. While that may have been true at some schools, the priests at the Jesuit college had the old-fashioned idea that schools were meant for studying. Low grades and the hot breath of expulsion on the back of his neck were the result. Basketball remained almost an obsession, however. And Bob took advantage of it. He had to remain scholastically eligible to play, and that meant study. Booking to stay alive brought his grades up and put sports on top again. He still gives the game a lot of credit for keeping him in college. Still, school didn't set all that well with him.

Basketball was his game, but baseball was gaining. Still, when the Harlem Globetrotters appeared in Omaha in 1957, he was asked to play on the All-Star team against them. And, though it wasn't in the script, the All Stars won. The result was a contract offer to Gibson if he would finish that tour with the Globetrotters. He was still in school, however, and declined. But he left the door open for a spot after school. Newly married to Charline, a girl he met through his brother's secretary at the Y, the Globetrotter offer was not enough to make ends meet. And, though he felt basketball was his sport at the time, he also had a fair reputation on the baseball scene and was hoping for a contract. The offer came, but not as he expected it would.

The St. Louis Cardinals contacted him, but at a much lower salary than he had in mind. Dickering ensued and he finally came to terms with the club — with the understanding that he could play for the Globetrotters during the off season.

Baseball meant Omaha for Gibson, with the exception of a month in Columbus, Georgia. He went into the "Triple A" American (Continued on page 55)

NEBRASKAland

A Country Kind of Summer

In this languid season, time is marked only by the number of stacks yet to be put up

WHITE BUILDINGS and board fences gleam against a backdrop of stately cedars and shimmering cottonwoods and are surrounded, by lush, emerald meadows.

The farther gray-green hills are sprinkled with sleek, red-and-white cattle, and impatient calves butt their mothers7 sides in pursuit of breakfast. A bucket clanks down by the barn and mewing cats converge on the steamy milk poured for them. A sun-bronzed rancher stands in the shadowed barn door with his foaming pail and watches as the warming sun begins to hum away the morning mist that lies low against the meadow. Milk cows tread a single path out into the sunshine, wet grass slapping their legs, their coats stirred softly by the early breeze. Indelible memories of morning magic are stamped on the mind.

The temperature climbs with the sun toward noon, and a dying wind summons hundreds of humming insects, driving cattle knee-deep into the sloughs. They stand mirrored in the welcome coolness, languidly chewing their cuds and steadily switching flies.

This idyllic spot in my daydreams is a cattle ranch in Nebraska's Sand Hills— our home. It's been said, that God made memory so we might have roses in December. So it is that we go about in summer storing away memories, much as we put up a bountiful harvest against harsher seasons ahead. I We hardly notice as days slip by, except to wonder at their (Continued on page 62)

CATS in the CEDAR

Record 13 inches of rain and flooding smashed the river. Still, my fishing urge reached a fever pitch

22NEWS USUALLY TRAVELS fast. But it was 5 days after 13 inches of rain fell on my hometown of Cedar Rapids before the news reached me in Wisconsin. The heaviest rain in the history of the Cedar Valley raised the water level on the Cedar River 18 feet, washing out or damaging most of the bridges in Boone County. For two days in mid-August, the river cut across fences, farmlands, and highways. When it returned to normal, it left three-foot sandbars across highways and fields, and had washed out several small lakes and gravel pits. New channels left several miles of riverbed dry.

The appearance of the river was greatly changed. Normally, Cedar River is a small stream running from north-central Nebraska to empty into the North Loup River at Fullerton. The sand and mud-bottomed river was 20 to 60 yards wide and, before the flood, averaged about 3 feet deep, with 6-foot holes a rarity. The flood seemed to have washed a canyon down the middle of the river. In many places the river almost stopped its flow, and stretches of river 10 feet deep could be found, plus a scenic waterfall.

My curiosity in seeing these natural atrocities matched my dread at seeing the damage when I returned NEBRASKAland

I was having amazing luck, considering I was fishing a small river that had gone back into its banks only a week before. Catching 10-inch catfish was a snap. A few 20-inchers also found their way onto my stringer. Returning the next evening, the action was just about the same and again I took home several 12-to-18 inchers, and one 26-incher weighed about 4 pounds. Now fishing fever really had me. The third night, I was back on the river, this time in a new spot.

The first of two lines was in the water. The second wasn't even baited when, with a sudden splash, a big cat broke water right in front of me. A short, but furious battle taught an 8-pound catfish that a 40-pound-test line can have a lot of sting. Before that night was over, another nine-pound catfish succumbed to the same line. Several much smaller cats put up a good JUNE 1970 fight on my six-pound-test line on a small spinning rod. If fish have emotions, I am sure they were not the same as mine when I returned home that night, for I slipped into sleep with high spirits.

The sun rose next morning on a clear, calm, and warm late-summer day. A day never dragged so long before. And, fishing again had to be put off until evening. That night the river bank again became a stomping ground for fishermen, this time for many more, as communications were back to normal and news of eight-pound catfish sends most small-river fishermen scurrying for their rods.

The fish did not disappoint us. We soon had many small cats, and before too long a three-pounder. For a while it was hard to tell who was coming out ahead, the river or the fishermen. For every fish caught, at least one line became snagged or broken. The odds, of course, were uneven, as the river had darkness and half-submerged trees on its side. The fishermen had the additional handicap of fishing from a 15-foot bank. After a while, either the fishermen or the river grew tired, for a lull set in. But not for long. The six-pound test on my spinning rod began to twitch, slowly slackening and tightening (Continued on page 59)

23

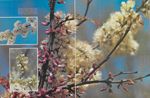

MARCH OF THE FLOWERS

In step with the season, wildflowers move across the land. They bear arms of greenery and carry shields of color

AS SHOUTING KIDS explode from schools to trample dirt lots and grassy fields, a quieter kind of rebellion is taking place. In undisturbed areas of NEBRASKAland, a host of tiny comrades proclaims its presence with waving banners.

First to conquer winter's silent white, small green shoots unfurl their flags of delicate pastels. Flowering currants blow myriad golden trumpets to waken scores of sleepy-headed violets.

Woodlands are covered by phlox and rose mallow armies. Camouflaged or nearly hidden under leaves, among grasses, and behind every rock, they sight in on drab enemies. The last vestiges of winter snipe at them with cold accuracy. A late freeze withers them. Cool winds stay their march, holding their ranks in a protected line.

Waiting soldiers shuffle threateningly, a stray ray of sun flashing off modest medallions of color. Plum branches provide their braid, dandelions their brass. Little ball cactus provides purple medals of valor, and generals are marked by small pink stars of sorrel. Chokecherry blossoms make plumes for marching soldiers' hats.

Dutchman's breeches stand ready like an earth-bound air force. And woods roses are Trojan horses beckoning with their pink flowers and attacking with prickles.

As the army of tiny lancers marches through woods and across fields, rebellion spreads into trees and bushes where redbud and plum assail the nostrils with their dizzying fragrance. Watches are synchronized by JUNE 1970 warming south winds and each battalion of color has its function.

Tiny lavender violets are the spies of spring. They steal forward into the camp of winter, seeking news of retreat. Starting in the more protected river valleys and wooded areas, they flit from rock to rock, from tree to tree, barely showing themselves. In time, they make their report that spring has arrived.

The prolific phlox are escaped prisoners of war. They eluded cultivation. As these aliens wander winter's stronghold, they persuade the landscape to join their party. "Acres of the world, arise," they chant. "You have nothing to lose but your pallor."

While "foreign" flowers weaken the last of winter's holdings, the bloodroot and fawn lily coordinate a take-over of the woods. Rose mallow and veiny dock lead an attack on the fields. Mariposa lilies sound the charge on the west.

The death of cold heightens floral activity as their ranks infiltrate just-greening grasses. Like dozens of grenades, they explode into bloom.

Gradually, though, even these proven warriors must yield to superior forces as summer flowers take over their positions. As the blooms shrivel and die, they form fruits which will perpetuate their yearly battle. Again, come spring, pastel blossoms will spread throughout the plains, vanquishing winter's colorlessness, opening the way for summer's riotous color.

Again they will send out their spies to report on winter's slow retreat, again bluebells will ring out victory with their tiny tinkle. THE END

25

Trees and shrubs join spring's rebellion

and offer their variety of blossoms and

buds to the season's arsenal of color.

Serviceberry, plum, and redbud perform

aerial maneuvers, while elms, bombers of

the force, drop seeds across the field

Trees and shrubs join spring's rebellion

and offer their variety of blossoms and

buds to the season's arsenal of color.

Serviceberry, plum, and redbud perform

aerial maneuvers, while elms, bombers of

the force, drop seeds across the field

CORNSTALK CONSTABLES

Dedicated to proposition that all sportsmen are created equal, this 49-man, law-enforcement agency is guardian of wildlife. Incidents range from the macabre to the ridiculous

WHEN A CONSERVATION officer of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission dons his badge each morning, he has no way of knowing what he may face that day. That 1 1/4 x 2 1/4-inch piece of metal may bring weighty responsibility or rest lightly on the green uniform.

Each day holds something new for members of this 49-man, statewide, law-enforcement agency. So, instances range from the macabre to the titillating to the taciturn to the downright ridiculous, but they make the life of the "cornstalk constable" what it is.

During the spring spawning activity of northern pike in Mother's Lake in southwest Cherry County, there is a certain attraction for people to illegally spear and shoot the fish when they are in shallow water. Each year, a number of arrests are made. Many anglers attempt to dash away as the law closes in on them, and others step right into trouble. Officer Jack Henderson of Stapleton strolled up to the lake one evening in his "civvies" and was greeted by a man with a pitchfork. Thoroughly soaked from dashing around in the water trying to pinion pike with his fork, the fellow asked Henderson if he had seen anything of the two conservation officers who had been hanging around earlier. He should have asked if the conservation officers had seen him, but he learned that in court.

On his day off, Officer Elvin Zimmerman took his family fishing at Merritt Reservoir near Valentine, his home and duty station, to sample the trout action. He knew that trout eggs placed in a nylon mesh worked well as bait, so he and his wife started having success almost immediately. Two anglers from eastern Nebraska, fishing nearby, sauntered over, complaining bitterly that fishing was bad, and marveled at Zimmerman's luck. Partly to prove fishing was better than the two men thought, and partly to be helpful, the officer showed them his method and gave them the necessary materials. Within minutes, the two strangers began dragging in trout.

"They were only one fish short of their combined limits when I left, but I resisted the temptation to stick around to see if they would break the law," Zimmerman concluded.

During the 1961 firearm-deer season in western Nebraska, Officer Cecil Avey, Crawford, stopped along the road to talk with a hunter. "There are just no deer around here," the hapless fellow complained.

While they stood chatting, Avey watched a three-point buck amble out of the timber, nibble some branches, and lie down under a tree. Although the hunter was also looking in the deer's direction, he didn't see him. Waiting a few moments for a break in the conversation, Avey said, "Why don't you shoot that buck over there?"

At first the hunter thought he was being sarcastic, but finally was convinced when the exact spot was pointed out, only a couple of hundred yards away. He subsequently downed the buck, and drove off, happy as a kid on the first day of summer vacation.

Law violators can get into funny situations, although their offenses are serious business at the time. Officer 34

Officer William Anderson of Lincoln was patrolling during pheasant season in 1962 when he saw a hunter carrying a rooster. Stopping the car to routinely check out the gunner, Anderson was surprised to see him make a dash for the safety of a cornfield. His escape was thwarted, however, when his britches got caught on the barbed-wire fence. An agonizing and painful few moments followed, then an arrest for not having a license and another "poacher" hopefully revised his hunting methods.

At the Two Rivers State Recreation Area, where alcoholic beverages are prohibited, Officer Bill Earnest, Riverdale, saw a couple fishing and sipping beside one of the lakes. He walked toward them and never saw them dispose of any containers, yet when he reached them, no beer was in sight. The woman was sitting innocently with her skirt spread out. After a few moments of idle conversation, the officer acted surprised and said, "Ma'am, I hope you're not afraid of snakes," and he gave a little jump.

"Where?" she shrieked, jumping up. As she moved, two six-packs of beer rolled from under her dress. All three were so tickled over the affair that Earnest doesn't even remember if he told them to get rid of the beer before he left.

Also at Two Rivers, while off duty and fishing like everyone else at the trout lake, Earnest heard an out-of-state angler complaining that Nebraska was a rotten state. He lauded his home state, but told everyone within earshot that hunting and fishing were terrible in Nebraska. After about two hours of this, he sidled up to Earnest and asked if he would like a few trout as he had over his limit. The officer replied, "Yes, in fact, I would like to have all of them!"

The law-breaker gave him an incredulous look, and the warden pulled out his credentials, announcing, "State conservation officer —you're under arrest for taking over your limit of trout."

Needless to say, there was no more haranguing about the culprit's home state, and nearby anglers seemed to enjoy the situation much more than he did.

During the 1968 grouse season, Officer Gerald Woodgate of Ord was patrolling in Garfield County and came upon a hawk in the road. Although a protected species, the hawk had been shot and its wings severed as souvenirs. Checking the area closely, Woodgate found a couple of Polaroid negatives, plainly showing four boys holding the hawk. After tracking the car to the highway where it turned east, the officer radioed a check station, alerting personnel to watch (Continued on page 54)

JUNE 1970 35

NEBRASKLAIand FESTIVAL OF COLOR PHOTO CONTEST

Start shooting and bag a prize. Open to all comers, pictures of state are must So, come snap your way to this fun-filled vacation

GRAB YOUR CAMERA and head for the action! NEBRASKAland Magazine announces its Festival of Color Photo Contest, designed to let you land a prize with a photograph that interprets Nebraska as you see it. The contest is open to everyone and anyone who can snap a shutter, excluding employees of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and their immediate families.

Here are the rules:

1. All photographs must be taken within Nebraska's borders.

2. Entries must be in the following categories: A. NEBRASKAland Scenics. B. NEBRASKAland Wildlife. C. NEBRASKAland Events. D. NEBRASKAland Outdoor Recreation. E. NEBRASKAland's People.

3. Submissions may begin at once. The contest closes December 31, 1970. Winners will be announced in the March 1971, issue of NEBRASKAland.

4. Only color photographs will be accepted. These include: A. Original color transparencies 35mm or larger, from any color transparency film. B. Color prints of any size from any color negative film. Color negatives should not accompany entries, but must be available, on request, if the picture is chosen for publication.

5. Each picture must have a completed, official entry blank or facsimile attached. In addition, the complete name and address of the photographer must appear on either the slide mount or the back of the photograph.

6. NEBRASKAland Magazine shall be granted publication rights to any photograph submitted in the contest. Such publication will carry the photographer's by-line, but no other compensation. Publication of a photograph prior to contest closing does not indicate it 36

7. All entries, except final prize-winners, remain the property of the photographer. They will be returned at the close of the contest, provided a stamped, self-addressed envelope accompanies the entry.

8. Winning entries become the property of NEBRASKAland Magazine.

9. Entries will be judged by members of NEBRASKAland's Art and Photographic staffs. All decisions will be final.

10. The Grand-Prize winner will win a thrilling, 14-day, fly-drive vacation, touring scenic and historic NEBRASKAland for himself and his immediate family. First prize in each of the five categories will be a spring or fall weekend holiday at a Nebraska state park for himself and his family. Second prize in each category will be a bound volume of NEBRASKAland magazine, while third prizes will be two-year subscriptions to NEBRASKAland. For details see box at right.

To help you determine in which category to enter your pictures, we offer the following suggestions:

NEBRASKAland Scenics is the place for nearly any picture with the surface of the land as its center of interest. A vista of the Wildcat Hills, rolling farmlands, or the Omaha skyline at sunrise qualify.

NEBRASKAland Wildlife accepts every non-domestic creature that creeps, crawls, swims, runs, or flies. A photo of a column of ants, a prairie dog chomping on a dandelion, a duck springing from a pond will find a ready home in this category.

NEBRASKAland Events encompasses photos of action-packed interest at state and county fairs, festivals, and celebrations of all kinds. Don't forget the dozens of rodeos all over the state.

NEBRASKAland Outdoor Recreation refers to hunting, fishing, scuba diving, waterskiing, hiking, trail riding, camping, and any other activity that makes use of the outdoors.

JUNE 1970 GRAND PRIZE14 fascinating, fun-filled days touring scenic and historic NEBRASKAland for the grand champion and his or her immediate family. This "perfect" fly-drive vacation features:

a Frontier Airlines flight from that airline's terminal nearest winner's home to Omaha, tour starting point, and back again at journey's end

two weeks' use of 1971 air-conditioned auto-mobile from Hertz Rent-A-Car of Omaha

lodging at Holiday Inns throughout NEBRASKAland

$500 expense money courtesy of BankAmericard

OTHER PRIZESFirst place in each category wins an exciting spring or fall weekend holiday at the Nebraska state park of their choice for winners and their immediate families, including lodging, swimming, horseback riding, and other available park facilities.

Second places win handsome, bound volumes of 1970 NEBRASKAland Magazine—a $10 value.

Third places win free, 2-year subscriptions to NEBRASKAland Magazine —a $5 value.

37

NEBRASKAland's People includes ethnic groups in colorful native costumes, or character portraits of the different races that make up the state. A businessman at his desk or a rancher or farmer at his chores all fit this category.

Since this is a full-color contest, your pictures will need a certain amount of technical excellence. Proper exposure, sharp images, pleasing compositions, and dramatic use of color all help to put your ideas across in a forceful, attention-getting way.

Camera movement may ruin what could be a fine picture. So, wherever possible, the camera should be braced against a solid object —a tree, the corner of a building, or the hood of a car. If no steadying object is handy, brace your elbows against your sides, hold your breath, and squeeze the shutter release as gently as possible. A tripod is fine insurance against camera movement but it isn't necessary for a clear photograph.

Just to prove that some rules were made to be broken, there are times when deliberate camera movement can be the salvation of a picture. When fast-moving subjects such as rodeo, sportscar racing, or a speeding waterskiier are involved, people who own simple cameras with fixed shutter speeds are often disappointed because moving subjects are badly blurred against a relatively sharp background. One way to cope with the problem is to swing the camera with the subject, keeping it centered in the finder, and, while following through in this manner, tripping the shutter. The background blurs out, while the subject remains relatively sharp. Surprisingly, the effect of speed is actually captured in the picture.

An overexposed color picture looks weak and anemic because too much light struck the film. Underexposed pictures appear muddy and dark because of too little light. Unless variable exposure was used to produce a special effect, any pictures showing these faults are not likely to be examined very closely by the judges.

Use of color is important too. A touch of red somewhere in a color picture adds a certain spark of excitement, even though other hues are present in quantity. However, gaudy or flamboyant color is not necessarily pleasing color. Rainbow brilliance is perfectly at home in pictures of the midway at the State Fair, but the mood of a misty morning on the Platte River would better be pictured in soft, muted tones of blues and greens.

Composition applies to the visual unity of your picture. Place your subject in the frame so the eye finds it instantly. This applies whether your subject is a bold one like Chimney Rock, or something less imposing. Walk around your subject, study the different angles and lighting effects in the camera finder. Look at it from ground level and from an elevation. Examine the effect at close range and then back away. Settle on the camera placement that presents the subject at its best. Then trip the shutter.

Watch backgrounds when you are working with a subject quite close to the camera. Usually, the less cluttered the background, the stronger the image becomes. Unless background objects add something to the story-telling value of the picture, they are best eliminated by changing camera angles. Except in rare instances, you can do without telephone or electric wires cutting across the sky or going through someone's head, or the church steeple that appears to grow out of someone's head.

Few good photographs are made by accident or by poking the camera out of a car window and snapping 38

In most scenic photos, it is desirable to include a figure to give scale to the mass. Normally, the figure should be far enough away to be quite small, since if it is too close, it competes with the scenery for attention, and you have something that is neither scene nor portrait. Let the figure be busy with something, not standing with his eyes fixed on the camera. You want him to appear unaware that there is a camera within a dozen miles. This tip, incidentally, applies to 99% of all photos of people. Any action appropriate to the subject being photographed adds interest and improves the chance the picture will be considered in the final judging.

Even though you adhere to contest rules and stick to the hints on how to make a reasonably uncluttered picture, you may still wonder which ones will stand the best chance of placing high in the contest. The judges will be looking for those that, through accident or design, awaken some positive reaction in the mind of the viewer. If the beauty and feel of wideflung spaces in NEBRASKAland are effectively presented in your scenics, if dignity and pride and joy of life are apparent in the faces of your people of NEBRASKAland, the pictures cannot help but be looked at a second time.

So, show us a laughing teenager having fun in the swimming pool at Ponca State Park, the pounding waves of McConaughy, or the rush of a startled deer heading for cover. Show us the beauty of your farmstead at sunset on a winter day, the flashing color of a powwow at Winnebago, or the tense features of a 4-rTer as his calf is being judged at the State Fair. Show us the wild action of a cowboy astride a brahma bull at a Burwell rodeo, a hunter and his dog working an autumn-frosted canyon, the bustle of an industry, or the quiet of an isolated town. All of these are worthy photographic subjects. And, within the fabric of NEBRASKAland there are countless others.

So, study the contest rules again. Then, start the entries pouring in. The judges are waiting. THE END

OFFICIAL ENTRY BLANK NEBRASKAland Photo Contest State Capitol Lincoln, Nebraska 68509 Name Street City State Zip Code Number in Family Category Where Taken Camera Used F/stop Shutter Speed This photograph is submitted with the understanding I agree to be bound by the rules of the NEBRASKAland Color Photo Contest as published in NEBRASKAland Magazine. For additional entry blanks use above information or write NEBRASKAland Photo Contest, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska 68509. Signed. 39

VIZSLA-POINTER SHOWDOWN

Idle banquet chatter leads to Fairbury match where issue is decided on hunt

THE TAN COAT of the vizsla blended into the dry December grass. We followed the dogs as they worked in and out of a small draw, thick with plum brush and elm, where the flashy white of the second member of our dog duo, a big spotted English pointer, was a contrast to the brown surroundings. As he emerged near the head of the gully he was joined by the vizsla on the grass-covered hill running up from the draw.

Seeing the dogs on the hill, we were convinced that the quail were somewhere else than in the draw so we hurried toward the end of the brush. Joe LaBass and I were on the left side of the cover, and farther back on the right were Jack Kenney and Clayton "Bud" Berggren.

Suddenly, quail were erupting from the edge of the brush between us and the dogs as a covey flushed wild. A gun boomed to the right when the birds rocketed over the brow of the hill. Two birds, late on the takeoff, were targets for Joe. I could tell he was shook as he fired wildly at the first bird disappearing over the hill, then whirled and sent another charge from his 12-gauge after the second one as it zoomed back down the gully. He didn't touch a feather. Since I had elected to carry a camera instead of a gun, all I could do was watch.

"Did you guys get one over there?" yelled Joe. "They sure surprised me." "Yeah, me, too," chimed in Jack as he and Bud appeared on our side of the brush. "I didn't stand a chance with the one I shot at."

Bud called in Spike, his eight-year-old English pointer, commenting, "I don't think those birds were coveyed up yet. They were all scattered out when they took off."

Bud, a city electrician in Hebron, told us earlier that he hadn't hunted that year without getting a limit of quail. We figured he knew his hunting.

"They may have just returned from feeding and flown directly into here. NEBRASKAland As calm as it is today, the dogs could pass quite close without getting a whiff of them," Jack ventured.

Jack, who had just delivered a baby before our hunt, is a doctor in Fairbury. He was the host for our dog match on the Little Blue River near Fairbury, and owner of Beau, a three-year-old vizsla.

"There's a milo field over the hill where they could have been feeding," added Joe, our official guide and impartial contest judge.

Joe's job as county supervisor for the Farmers Home Administration puts him in close contact with farmers and their land, so he was a natural as a guide. He had also lined up Bud and his pointer, Spike, to hunt with Jack's Beau.

"I saw about a half dozen of those birds fly back up by that field," Joe continued. "Let's go see if we can find them."

That was the slow start of a rather unusual quail hunt that began about 200 miles from where we were standing. The idea was born in Broken Bow during the Annual One-Box Pheasant Hunt.

As part of my job as a photographer with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, I was there covering the one-box hunt for NEBRASKAland. At the awards banquet I was talking to some of the shooters on the Nebraska team. Among them was Jack Kenney, and naturally the talk was about hunting.

As the conversation progressed, Jack made some statements like: "We have the best quail shooting in the state," and "Why don't you come down to Fairbury and I'll show you a real quail hunt."

The conversation shifted to hunting dogs, and everyone agreed that a pointer or setter was the only breed to really hunt quail with. Everyone, that is, except Jack. He said, "I have a vizsla that is all the quail dog I need."

Jack's declaration had raised some controversy in the group, especially since the vizsla breed was relatively JUNE 1970 new to Nebraska and not well known as a quail dog.

I don't know if Jack made any converts that night, but he started me thinking about a possible story for NEBRASKAland - a match between a traditional quail dog — a pointer — and Jack's vizsla. Jack agreed to the match, but it was the following year before I arrived in Fairbury to hunt.

It was 10:30 a.m. as we drove northwest from Fairbury. Jack explained why we were getting such a late start. "Usually, about 8 a.m. the birds head for milo or corn fields to feed, and when they're done they head back for the heavy cover along the river or in fencerows. We want to be sure they're back."

Joe stopped the car about a half mile from the river and we let the dogs out. Within five minutes we were surprised by the covey that flushed wild.

Now we approached the milo field in a loose line with the dogs bounding ahead. Expecting some action at the edge of the field, we were disappointed when the dogs broke into the open without a point. Jack returned my what-the-heck-is-wrong look with a shrug of his shoulders. Then I almost stepped on a tight-holding quail that exploded in my face and headed over the milo field. My "There goes one" was punctuated by a blast from Jack's 20-gauge automatic as he collected the first bird of the day.

No sooner had Beau completed a perfect retrieve than another nervous bird whirred out beside Joe. This time our tall guide calmly dropped his target with one shot.

"The dogs aren't getting the scent," called Bud as he took Joe's quail from Spike. "I can't figure it out, unless it's just too dry this morning."

We looked in vain for the other birds we knew should be there. Then Joe suggested we head for heavy cover down by the river. I couldn't resist a detour past the car to pick up my shotgun. Slinging my camera around my neck, I turned the polychoke on my 12-gauge pump to "improved" and hurried to catch up.

We worked a wide strip of cover sandwiched between the river and a cut milo field. Jack mumbled, "I hope the scenting is better down here," as he followed Beau along the fencerow.

Then his tone became excited as the tempo of the vizsla's tail wagging increased. "Beau is on to something! Watch out!"

Beau locked into a point and we closed in. When the covey flushed, two birds shot across the milo. I managed to drop one and was swinging on the other when it fell to a blast of 7 1/2's from Joe, who collected his second bird. Jack also scored his second.

There were about 15 birds in the covey and they went only about 100 yards up the fence row before putting in again. Both dog contestants put in some fine work as the vizsla, then the pointer, zeroed in on singles. One fell to Jack and another to Bud, who broke into the scoring column.

As Joe shoved a shell into his gun he said, "I think we had better let up on this covey. It's a small one, and I like to leave at least 10 birds so they can build back up next year."

As if they understood, the dogs immediately left the fencerow and headed into thicker brush and trees near the river. They hadn't gone 50 yards when Spike coasted to a stop. Beau swung around and locked in. It was some picture, the two dogs frozen on point while Bud and Jack approached. Unfortunately, Joe and I were still crossing the fence when the covey busted out toward the river. Bud made a nice double, but Jack drew a blank when the bird he picked took advantage of a convenient tree trunk.

It was a big covey, about 25 or 30 birds, and when we began finding the singles, the action really started. Bud was first to score when Spike made a striking point right at the edge of the river bank. The bird was under the cut of the bank, almost in the water, (Continued on page 64)

41

Portraits of the Past

THIS MONTH, NEBRASKAland presents the second and final selection of American Indian portraits, courtesy of Rinehart-Marsden Studio in Omaha.

The product of F. A. Rinehart, early Omaha photographer, the photographs are again accompanied by Indian poetry by Frank V. Love of the First Reformed Church of the Omaha Indian Mission at Macy.

Like those appearing in the May issue of NEBRASKAland, these photographs, too, were taken at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, held in Omaha in 1898.

NAMES Standing Soldier Eagle Chief Red Sleeve Black Hawk These names beat Brown Smith and Jones all to heck WAR PAINT AND CHRIST My lance silent My arrows for play My ways are turning The white flood has come The old prophets told us The ears of many were closed He spoke to me He called me son He said come and eat Now I feel good Never more hungry No more sad, no fighting THE RED MAN'S BURDEN When foreign shores knew chaos Hiawatha taught democracy When mercenaries killed foe and friend Black Hawk forbade Englishmen to torture prisoners When a white captain would have died Pocahontas risked her life to save his When Lewis & Clark headed West, Sacajawea with her babe led the way When Custer's pride overruled reason Sitting Bull replied at the Little Big Horn When Ishmael could find no friend among his own Queequeg became his bedfellow and redeemer When men, women, and children starved at Plymouth Massosoit and Samoset brought corn and meat When the great curtain of time is pulled back and all is made known what burden will you bear? 42 GOOD MEDICINE Somewhere way off There is the great Buffalo Spirit He makes my arrow true My heart strong My mind clear My people clean When I stand up in my tepee The cedar smoke is sweet This is good medicine A FADING LEAF The leaves are falling again Soon frost will cling in their place Across the street, Harry Huiswaard Will be raking leaves and counting Harry doesn't talk much about religion, Just the leaves and the weather The leaves are old now, so they fall Harry is not young, only seventy-seven Soon the leaves will be gone Harry, too, will no longer lift the rake Where will Harry go... Leaves, leaves, and more leaves HOMEWARD Man! God....... I hate to go home this time. When I hit the Reservation line My lips wont hold their shape The old tears will start to flow And see the trees around the yard and all the familiar things I know My family and all our friends standing around Dont know what to say... Dont know what to do... Man, I hate to say good-bye It just wont be the same anymore Please dont put 'em in the ground Just kinda hold it off awhile Man, I hate to come home this time FRIENDS If a man has many some that cry when you share the gift of your selfhood Then there must be enemies too Those that hang on you draining all you have Others merely using your usefulness to flood into an unweeded garden There are friends ...and then there are friends God give me the insight and gift to know the difference NEBRASKAland

Red Buffalo

Like a wild herd, fire stampeded across the prairie in 1910, leaving destruction in its path

RED BUFFALO, the Indians called it. And, in the spring of 1910, prairie fire swept across the plains leaving smoking, blackened crops, animals, and homes in its wake— all because one man preferred life as a loner,

Names have been lost in time, but western Nebraska legend has it that in the early years of this century a man we'll call Bill Springfield moved into the ranching country around Antelope Flats,60 miles north of the North Platte River — alone. His neighbors paid him a visit, to be friendly, and to warn him of an unwritten law in the Sand Hills, The "law" required a man to burn a firebreak only when his neighbors could help control it. Being a self-sufficient man, Bill snarled something like, "And what if I don't want any help?" His neighbors took the hint and left.

Spring wore into summer, and Bill built a house and a barn. He harvested hay and put it up. Then, to protect his investment, he began to plow trenches for a firebreak.

His protection consisted of two rings plowed around the house and barn, one ring inside the (Continued on page 62)

JUNE 1970 51

CHANGING FACE OF CONSERVATION

(Continued from page 17)break the basic food chain necessary to maintain the gulf as one of the world's great natural fish traps.

Some say it's already beginning to happen. North America's largest cesspool, Lake Erie, is well known to all of us. Why not the gulf?

Most of us are acutely aware of the dangers of a poison when consumed by living creatures, but how many of us have ever stopped to consider the even greater threat —the changing of whole environments. A poisoned critter can get well, but destroy his home and nothing will save him —except a zoo!

We farm the land clean. We no longer tolerate the sunflower, the thistle or pigeon grass. With clean farming we create a new environment of hundreds of thousands of acres of single kinds of crops — perhaps wheat, corn, soybean or cotton. We create an ideal situation for that particular insect that specializes on certain types of crops.

Because the threat of damage is increased so profoundly we flood our fields with chemical sprays — sometimes once, sometimes eight to ten times a year. We keep the detrimental insect problem in hand, but along with it we destroy the beneficial insects.

The young of bobwhite quail or pheasants or grouse, simply cannot survive without the supercharged protein foods that insects alone can provide. Thus, even though we find only minute traces of an insecticide in the young bobwhite, he may ultimately die.

Insecticides and herbicides accomplish two things — they eliminate insect life at a critical time of year and they transform a habitat made up of many parts into a habitat made up of a single part.

Wildlife cannot survive in a single-purpose environment anymore than it can survive in your living room.