NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

May 1970 50 cents • Second Installment: Beauty by Design • Epoch of Life • Indian Portraits • Mixed Bag Hunt at Sacramento • Take a Nebraska Ranch Vacation • Bright Eyes, a Tale of Two Worlds

A Family Affair

For family fun, NEBRASKAland's great outdoors is the place to be. There's no generation gap on the shores of a sparkling lake or rushing stream. There, everyone speaks the same language — the language of Nature. There's nothing quite like the aroma of fresh fish sizzling in the pan over an open fire to draw folks together. Mom, Pop, Sis, and Brother can all get hooked on the family affair of fishing. To make the excursion more productive, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has published a free brochure, "Where the Fish Are". For your copy write to NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, 68509. And, your friendly, neighborhood permit vendor has the tickets for months of pleasure. Remember, the family that fishes together, grows together.For the Record ... ACRES FOR WILDLIFE

Around the end of World War II, in 1945, Nebraska boasted 18 million pheasants. By 1959, that number dropped to around seven million. Last year, the count revealed just three million. So it goes, the story of Nebraska's "bread and butter" game bird —the ring-necked pheasant.

Nebraska is not alone in its decreasing supply of pheasants, however. South Dakota had a whopping population, around 13 million in the 1940's. Today its population, too, is nearing the three million mark. Oklahoma also is losing game birds — bob white quail —at an amazing rate, as are other states whose basic industry is agriculture. But game birds are not the only casualties. Animals, both large and small, and song birds are similarly affected.

Ready answers to the cause of this decline can be heard in almost any drugstore, barber shop, and most certainly in the sportsmen's clubs across the country. Some of the most common cries are that hunting seasons are too long, weather is hindering development, predators are ravaging bird populations, and pesticides are spilling over into the game-bird realm.

In Nebraska's case, at least, most of these claims are false. Or, at best, they are only half-truths. The state has restricted hunting to the male of the species since 90 percent of the roosters are surplus to production needs. Only about 50 percent are being taken annually by hunters, so it is apparent the long-season argument doesn't hold water. And, while weather causes fluctuations in the pattern of bird populations, the general decline has continued through good years and bad. Pesticides and predators are certainly able to kill individual birds and we are also aware of several other effects of pesticides. But we should not allow these things to focus our attention away from the real issue —COVER —or rather, the lack of it.

Unlike many other states in the same situation, Nebraska is taking steps to remedy the problem. One such step is the Acres for Wildlife program, designed to fight the continual problem of dwindling cover. Young people, as well as adults, are encouraged to acquire the use of plots of land at least one acre in size. These plots are to be maintained in their natural state or be planted to cover where wildlife can nest.

Program goals are threefold. One is to get people actively involved in a conservation program. Another is to establish participant-landowner relationships which will grow and foster goodwill between the two. And, the program is to provide much-needed habitat.

Of course, cropland acres are important and can and do qualify for Acres for Wildlife. But the program is designed to neither compete with nor hinder normal farming operations.

While conservation is frequently thought of as a group affair, Acres for Wildlife also welcomes individual enrollments. More than 400 individuals are now active in the program. And, many Boy Scout troops, school classes, FFA chapters, rural schools, and wildlife clubs have been among the first organizations to join.

Most people involved in Acres for Wildlife are dedicated to conservation and expect no pay or reward. Yet there is an ample award system. Conservationists receive award certificates for both participants and group leaders. Arm patches and plaques go to individuals and groups for acres enrolled. And, a free subscription to NEBRASKAland is given to participating landowners.

A letter to the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission will bring all details. Enrollment is a simple process and qualifying plots are not hard to find. So, why not join the team. THE END

MAY 1970Go Adventuring!

This is the Old West Trail country, big and full of doing. Stretching from one end of the setting sun to the other, this inviting vacationland will ever be the place for your family to go adventuring. Here, the horizon-wide scenic vistas defy description. The trail is a series of modern day highways, mapped out by state travel experts. Look for the distinctive blue and white buffalo head signs which mark the Old West Trail. Sound inviting? You can bet it is! Go adventuring on the Old West trail! For free brochure write: OLD WEST TRAIL NEBRASKAland State Capitol Lincoln, Nebr. 68509

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

LION ABOUT NEBRASKA-"I have been one of your ardent readers for the past year. The Lions of Nebraska have a state to be proud of and the people of your state can thank the Lions of Nebraska for sending copies of NEBRASKAland to Lion District Governors around the world.

"My family and I read all the articles with interest and have admired the wonderful photography. I thank the Lions of Nebraska for this fine and thoughtful gift '-William D. Moody, Mount Forest, Ontario, Canada.

TIME FOR CRANES?-"According to records kept by the Brooking Bird Club, we always see cranes in February, often earlier and some have been observed in January. They stay until mid-April, most of them apparently, and we saw one straggler on a spring bird count May 7."-Ellen R. Ritchey, Hastings.

You are right in noting some early Sandhill Cranes show up in the state in February. Also, we agree that during certain years, some come in as early as January. The arrival and departure of cranes is extended over a fairly long period. The spectacular numbers are present from mid-March to early April. A few stragglers may remain as late as early May. — Editor.

RABBIT FEUD-"I want to thank Mr. Dreyer for coming to my defense with his Speak-Up letter. There are two kinds of jackrabbits, but you are wrong on the 4 size. The blacktails are the big ones, or were in the 1930's. Back then, the jack-rabbits were called bunny rabbits and bush rabbits. We often called the white-tailed jackrabbit a cottontail."—Jean Miner Schroer, Kearney.

The blacktails that Mrs. Schroer saw in the 1930's may have been larger than the whitetails. But according to Nebraska Game Commission biologists, the white-tailed jackrabbit is the larger in average weight and size.— Editor.

BOSH-"As a reader of NEBRASKAland, I, together with many other subscribers, am deeply incensed by an article of 'propaganda' by Fred B. Nelson, entitled The Platte River Dam. The article is completely misleading. It states 62,000 acres. In fact, it calls for 126,000 acres. Also the price tag. Instead of $490 million, it is closer to three billion, as there are nine hundred million dollars worth of sand and gravel alone.

"Calling this proposal 'manna from heaven' is as far from the truth as anyone could get. This valley has 8,000 citizens creating millions in new wealth every year."—Bert E. Chavet, Waterloo.

SAND SLIDES —"I enjoyed the article in the March issue of NEBRASKAland on The Shifting Sands. Do you have 35 mm slides for sale on this and other articles?" — Alfred A. Jorgensen, Fairmont.

All color pictures which have appeared in our magazine can be purchased. They must be produced on special order at this time, however. Slide cost is $1 each with a minimum order of $5. This does not include applicable sales tax. — Editor

FIGHT POLLUTION-"Born in Gage County, raised in McCook, I did a bit of roaming and since I have retired, I am beginning to feel the call of the Sand Hills.

"Even though I reside now on the North Fork of Eastern Long Island, I am involved in the conservation and preservation of our natural resources. Here, this is a real problem because of the population migration to our once quiet, clean, and beautiful area. Industry is defiling the air and water resources and the influx of careless people is creating at least six pounds of refuse per day per person, some of which is strewn along our roads.

"Yes, Nebraska is still wide open like the ad portrays on page 52 of the January issue. Please don't let this great space overcome you. There will be people who will want to 'blacktop' the whole state to reduce taxes, but the records show this is a fallacy and only the promoters enjoy the fruits of this destruction.

"But I am more concerned with your beautiful Nebraska lakes. You are polluting all of your lakes with gasoline and oil from boats, and at the same time, trying to keep these lakes stocked with fish. Gas and oil pollution together with lead deposits from exhaust will eventually kill many algae and plant life that are necessary to keep fish healthy. The mud on the lake bottoms will gradually load up with pollutants and thus destroy some of the food that bottom-feeding fish need.

"You only have to read up on the boat population of the country to see what is sure to come. Already many of the harbors on Long Island have been so polluted that most edible fish have either died or migrated. This is not a nice picture, but in 1967, '68, and '69 I fished on Johnson Lake. It was possible to observe the increase in boat population each year, and in 1969, there were so many boats, that fishing became a physical hazard.

"I hope Nebraskans will get off their hands and take the necessary steps to insure the safety and purity of their lakes." — Harold Search, Mattituck, New York.

ARE YOU KIDDING-"Stories have been told about mountain lions running the river bottoms along the Little Blue River, but no one has ever shot one. A friend of mine was hunting along the river one day when he saw what he thought was a coyote moving through the timber. To his surprise, it was a deerote. Yes sir,

that's what it was. It had a four-point rack like a deer and a body like a coyote. Must have been one of those freak animals like a jackelope. Lucky he took this picture of it or no one would have ever believed such a story. But here it is in black and white just like he said." —Tom Morrison, Gretna.

BIG CAT —"When I was teaching school in Blaine County near Brewster, a lion was seen.

"A rancher living northeast of Brewster, heard his dog barking furiously one night. The next morning he found large animal tracks in his yard, leading north up into the hills.

"He backtracked the trail. He traced the big tracks south from his place along the road that went by the schoolhouse and my trailer home, but he soon lost them.

"This was in the spring of 1964. Nothing more was known about the big cat NEBRASKAland for several months. People could not believe there really had been one.

"One evening that fall, some men who were doing late chores at a large ranch about three miles south of my schoolhouse, heard the scream of some animal. They knew it must be the mountain lion.

"I warned the school children not to go out into the pastures alone, especially in the evening.

"Some of the ranchers reported having stock killed. One man lost a cow and a calf. Another lost a horse.

"A rancher living near Almeria who owned and piloted a small plane, searched the hills, valleys, and blow-outs and finally discovered the animal —a tawny colored creature about five feet long with a long tail.

"The rancher was not successful in getting the lion."—Gladys Baldwin, Newport.

ARTIFACT COUNTRY-"How about an article and pictures on the fine artifact collection of the late Amos Hart of Bassett? He collected a fine array of Indian artifacts during his lifetime.

"As you know, Wyoming is the heart of Indian Country, and we have very fine collections all around here. But Hart's is as fine as any I've seen.

"Mrs. Hart lives in Bassett and teaches there. I'm sure she would co-operate." — Lavern L. Shortt, Powell, Wyoming.

We will check into the possibilities of such an article in the coming issues of NEBRASKAland. - Editor.

BUCK WITH A BOW-"In June, I bought my first bow and applied for a deer-archery license. On November 22, 1969, I shot and killed a six-point buck. This in itself is significant. But on that same day I also shot three pheasants, plus one week prior to November 22, I shot my first deer with a rifle, a two-point buck. These facts and the exciting incidents leading up to the kill of the six-point buck have indeed made this a memorable hunting season for me.

"The six-point buck is being mounted at this time and is awaiting measurement for the Pope and Young Award and the Nebraska big-game citation." — Chuck Barton, North Platte.

MEMORIES-"I am now 82 and during my years in Nebraska I have hunted and fished from the Missouri River to the Sand Hills. Some experiences stick in my memory and I would like to share them with NEBRASKAland's readers.

"When I was about 14, I used to fish Cut Off Lake now called Carter Lake. At the time there was a partially sunken paddle-wheeler there and I used to fish from it.

"Every spring, I used to go to Oakland, Nebraska to hunt ducks (spring hunting was legal then) and build a blind out of hay. One day, I was sharing a blind with my brothers-in-law waiting for the ducks to come in. The birds came in, but they were too far away, so we decided to sneak them. While we were crawling, a flock of geese came over so low we could almost touch them, but we didn't shoot.

"Most guns in those days had outside hammers, so one of my companions decided to cock his double-barrel before getting in on the ducks. A cornstalk caught in his trigger guard and the ensuing "boom" sent thousands of ducks soaring into space. No geese, no ducks.

"Back in 1910,1 was hunting ducks at the Logan Ditch near Oakland when a flock came in and settled out of range on the west side of the ditch. I was working my way around to them when I saw a lot of feathers scattered on the ground. Thinking that other hunters had cleaned their birds there, I went on. The shooting was good, but one of my birds fell out in the marsh. I left it there intending to pick it up when I started for home. A coyote came out, picked up the duck.

"I gathered up the other ducks and started home and a half dozen coyotes started following me. They trailed me almost to the farmhouse but never got within gunshot. As I neared the house, the dogs came out to meet me. The coyotes heard them, made one big whoop, and took off into the darkness." —C. H. Krelle, Omaha.

WHY NOT ELK?-"I recently got hold of some 1968 copies of NEBRASKAland from my high school librarian and I noticed a very good picture of an elk on the cover (June 1968).

"Could you tell me how many elk live on the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge? I would also like to know why it would not be feasible to start a herd in the Halsey National Forest or the Oglala Grasslands with the prospect of very limited hunts in the future." —Kurt Lash, Wayne.

There are, roughly, 35 elk on the Niobrara Refuge. With the exception of one or two years, production has been very poor. It is doubtful that elk would be compatible with normal ranching operations. Therefore, it would be a necessity to maintain the animals on public lands, requiring fencing costing over $2,000 per mile, plus major maintenance fees.

The Oglala Grassland and the Forest Service lands in the Pine Ridge would be eliminated because of interspersion with private lands. And, habitat on the Grasslands would be a long ways from what is desirable for elk.

The Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest near Halsey would be large enough to support possibly 100 elk. However, this would necessitate some loss in other wildlife such as deer. And, the cost of fencing would be near $50,000, a poor investment for a harvest of 20 or so elk a year. — Editor.

WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM 5

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . JOHNNY DARTER

Known as the hummingbird of fishes, this tiny Nebraskan gets his name from his speed

SOMETIMES REFERRED TO as the hummingbird of fishes, darters are diminutive members of the perch family Percidae which includes the familiar walleye, sauger, and yellow perch. This reference is drawn from their swimming habits as they dart from one spot to another, stopping as suddenly as starting, and sinking to the bottom. Often they remain motionless among the rocks for long periods and, on occasion, perch atop stones supported by their pectoral fins.

There are 95 types of darters in eastern North America. Only one type exceeds three or four inches in length. Darters are uncommon in Nebraska with the johnny darter, Etheostoma nigrum, (Rafinesque) being only one of four known species (Iowa, orangethroat, and Blackside). Records of existence in Nebraska usually date to early-day collectors who noted it in the Platte River at Kearney in 1860 and from the Elkhorn and Missouri Rivers in 1894. The johnny darter was found in the upper end of the West Fork of the Blue River in 1931, in Lodgepole Creek in Deuel County in 1942, and again in Kimball County in 1969.

Often thought of as a minnow or perhaps confused with small walleye, the johnny darters prefer small, MAY 1970 springfed streams with sand and gravel bottoms and moderate currents. Their body forms resemble other family members. However, the dorsal, anal, and pectoral fins seem too large for his size. This adaptation serves him well in the faster currents where he resides. Also, the tail is unforked or only weakly so. Additional features include a streamlined body, pointed head, and no functional air bladder, which makes him heavier than water and facilitates his bottom-dwelling habits. The air bladder in other fish serves to maintain equilibrium and aids in hearing.

Body coloration outside the breeding season is sandy to greenish on the back with distinct markings along the side that appear as the letter "W". The belly is milky with no scales on the breast or cheeks. Dorsal fins have spotting that forms oblique rows, and wavy vertical bands are present on the caudal fin. Lower fins are usually unspotted.

During the April or May breeding period, the female remains about the same color. The male, however, becomes blackish over the entire head, breast, pelvic, anal, and spinous dorsal fins. The remainder of the body and scales become dusky and between four and eight vague, blackish, vertical bands cross the body and are most distinct toward the tail. In addition, soft, whitish pads are developed on the tips of most of the dorsal spines, the ends of the pelvic spine and rays, and the anal spine and first ray.

It may be an upside-down world to the johnny darter when he begins life. His parents were inverted when the eggs were spawned and attached to the underside of a stone or other object. The male is territorial and females seldom intrude until ready to spawn. Attracted into his small empire, she follows him under a stone where courtship precedes the unusual breeding behavior.

In the animal kingdom, the greater the parental care given, the fewer offspring result. This is true with the johnny darter as females lay only from 30 to 200 eggs, deposited singly. Rarely are two or three eggs laid one immediately after the other. In addition, the eggs are laid in clutches of five or six. Between clutches the female often rests upside down on the dorsal fin or momentarily resumes an upright position.

The male opposes all others regardless of size, and will defend against fish three or four times larger, however he is not averse to welcoming two or three females into the nest.

The young would probably rest a little more comfortably if aware of the fatherly attention. He selected the spawning site, cleaned it with his fins, and kept silt off the eggs by brushing with the spongy back of his neck or turning over and using the soft fin pads or by simply fanning his larger pectoral fins to create water currents. He also eats eggs that die or develop fungus.

From all this vigilance, it seems unfair that life will only last a few years. But during this relatively short time, his length will seldom exceed three inches. Food consists of minute Crustacea and insect larvae. The johnny darter himself seldom becomes the diet of other fish, which is related to his secluded life among the gravel of small streams.

Of all darters, the johnny darter appears to be more tolerant of nature's stresses and can inhabit waters more silty than those tolerated by others of his clan. Regardless, Nebraska is on the western extension of his geographic range and he will remain limited in distribution. The johnny darter may not be of importance to the sport fishermen and his solitary life may continue virtually unnoticed, but he is a busy member of our environment. THE END

9

Sunny Side Up!

Put your plate where your mat is.

HITTING THE BEACH

BRIGHT SEPTEMBER SUN glistened off the waters of the sandpit near Lin wood, and the four youngsters chattered excitedly as our 100-horsepower catamaran purred along. We were all engulfed in the beautiful day and the dozens of wild ducks flying and swimming about. Nowhere in this peaceful setting was there a hint of the moment of terror that awaited us all.

I was at the controls My passengers were my son Robert, then 7, brother-in-law Henry Malik of Yankton, S. D., and his sons Tom, Jim, and John, ages 5 to 13.

The irregular shoreline of the horseshoe-shaped lake lazed by as I glanced down at the speedometer to clock a duck flying alongside. The dial registered just 12 miles per hour.

I've been a serious boater since 1947, and in the course of the many miles I have logged on the water, I acquired a strong respect for safety rules. So, I was more than a little disturbed when I glanced back and saw the five-year-old dangling his hand in the boat's wake near the props.

I turned to correct him and give him a short lecture, but when I looked back forward, I discovered to my dismay that my preoccupation with one safety rule led to the violation of another and put us all in a bind. We were heading for the bank, and I just had time to crank the controls hard to the left before we hit the shoreline

An instant after impact with the bank, we were experiencing the weird sensation of cruising over dry land. Another instant and things began to happen, A fence on the boundary of a pasture loomed ahead and I could do nothing to avoid it.

Barbed wire sang and twanged as it whipped over our heads. Fence posts flew around us like straws in a gale. Then, a split-second later, we were floating peacefully in the water again, miraculously unharmed and showing no apparent signs of our misadventure except jangled nerves and wide-eyed expressions.

A half-hour and several nerve-calming cigarets later I went back to survey the scene. As I looked it over, I was shaken all over again. We had sailed a semi-circular course that had taken us 25 feet into the pasture. On the way, the boat popped a three-strand barbed wire fence like spaghetti, snapping four wooden posts and a steel one like match sticks.

Luckily, the windshield and the high profile of the twin outboards kept the barbed wire from whipping NEBRASKAland

Other than the mangled fence and some flattened grass, the only sign of our brief, but eventful, detour was a pair of neat grooves cut into the turf by the skegs of the outboards.

To top off our incredible good fortune, an inspection of the boat showed the only damage was a small scratch where the prow had mowed down the posts. Not even a nick appeared in the props after flailing wildly over dry land.

After taking stock of the situation, I approached an incredulous farmer with news of the demise of his fence and offered to pay for the damage. "A boat?" he blurted in disbelief. "I've had cows, horses, cars, and trucks take out my fences, but a boat?" he gulped.

I can thank my lucky stars we were looking at ducks instead of conducting a racing demonstration. MAY 1970 The twin-hulled catamaran is one that I designed and built myself, and it is fast, indeed. With the twin 50-horsepower outboards wide open, I know the boat is capable of more than 45 miles per hour. If we had been going at any speed at all, someone could have been killed or badly injured.

Looking back on the incident points out a valuable lesson I could have learned the hard way. Now I know enough to keep my mind on where I'm steering the boat, A boat's skipper might still have to correct someone while on the water. But, extensive safety lectures should be delivered before the boat is ever launched. Word of our hair-raising experience soon got around to my friends, resulting in some kidding and good-natured ribbing. It's not something that I'm very proud of, but at least it serves as an example that might keep others from making the same mistake. THE ENDTravel the Safe Telescoping Trailer Way..

HOW TO PACK A BAG

Wrinkles are things of the past with these travel tips

VACATION TIME HAS finally arrived. You've reached your destination and the weather is fine. Time has come to unpack all those cool vacation clothes and enjoy the sun. You open your suitcase and — well it is a good day to stay in your hotel room, waiting for your clothes to be pressed.

There is a way to stave off the vacation-wrecker. The following tips will help make packing a breeze and unpacking more enjoyable.

The first essential in packing is luggage. If you haven't already got your luggage, now is a wonderful time to acquire the pieces that are tailored to your personal needs — present and future.

For the ladies, three or four cases are basic, although not all will be used all the time. These should include a pullman, 26 or 30 inches, depending on the lady's height — dresses should fit the suitcase with just one fold. A dress carrier may substitute for the pullman. The second piece is a tote bag or a cosmetic bag, and the third is an overnight bag.

For men, a two or three suiter, depending on individual needs, or a companion case, is almost essential.

12For short trips a carry-on may suffice; and an attache case is also handy. If every person in your group, including the kids, has his own luggage, it is easier to sort belongings on overnight stops or even at your final destination.

Before starting to pack, make a list of things that are to be included. Leave yourself plenty of time, because hurrying will cause some wrinkles, especially for the novice. Plan your packing. Each item has a place where it will best fit —and best be found when needed.

Take time to get acquainted with your luggage. There may be advantages you didn't even know you had.

When choosing garments to go traveling, pick double-duty clothes; clothes that mix and match with each other and with the occasion. Basic colors allow for limited accessories — like shoes. Sleeveless dresses with jackets are nice for women. And, be sure all accessories for each outfit are laid out. You're living in a wonderful age for travel. New fabrics pack without protest. Be sure you take advantage of them.

Once everything is gathered together, survey the situation and start packing. Button all buttons, zip all zippers, and start putting things in your suitcases.

To pack dresses, hold each garment by its shoulders, fold it in thirds, turning the sides back, and smooth the sleeves. Lay the shoulders at the right edge of the suitcase and drape the skirt over the opposite side. Place the shoulders of the next dress at the left edge of the case and fold the skirt of the first over the shoulders of the second. Continue to alternate until all dresses are packed.

Baggies are good for keeping hose, socks, and other small items together, and sorted from other items. To save space, tuck small things in small spaces left between larger garments. Most small things will usually end up in an overnight bag.

Pack each shoe in an individual plastic bag to keep the luggage-carrier happy. Separate bags may be used to distribute weight throughout the suitcase -and shoes, no matter how far separated, are not hard to relocate.

Men's slacks are folded much like women's dresses. Place the waistband at the right edge and drape the legs over the left edge. Continue to alternate until all slacks are packed.

Always remember that the tighter you pack, the more wrinkles you will press into your clothes. Sometimes its better to carry an extra bag than to pack too tightly.

Before leaving home, be sure you have insurance on belongings — and labels on bags. Have a second set of keys made for your bags.

On reaching your destination, unpack immediately— waiting may bring wrinkles. Decide how to allot space, which drawers belong to whom, which side of the closet is best for her and which for him. Hang the kids' clothes in a separate place. Keeping clothes separated saves bumping into each other when dressing for the rodeo.

If you don't unpack everything, leave the suitcases in a horizontal position. Otherwise, you may find all your carefully pressed clothes in confusion.

If your packing has left some wrinkles, hang your clothes in the motel or hotel bathroom and turn the shower on—very hot. After a few minutes, turn it off again and close the door. Your clothes will steam smooth quickly. Don't leave them too long as they will become limp.

Use the hotel safe or lock valuables in your luggage when leaving your hotel room.

Relieved of clothing worries, almost any trip can be more relaxing. So pack your gear —careful now — and head for those NEBRASKAland fun and sun spots. THE END

NEBRASKAlandAn unsolicited testimonial to Frontierland from Katharine Lee Bates.

Just one more slough

Niobrara River bass call modern Huck Finns to explore another bayou just around the bend

14DON SCHROEDER and Lee Jackson cast apprehensive eyes, first at the slim silvery silhouettes of the canoes, and secondly, at the ominous cloud cover. "Either way we look at it, Gene," Don grinned, "if that 'widow maker' you call a boat doesn't get us those thunderclouds will. However, the thoughts of the fish waiting downriver outweigh my little misgivings, so let's shove off."

The paddles of the two voyageurs bit into the swirling currents of the Niobrara River and their 16-foot canoe surged away at a fast clip. I hesitated a minute before pushing our canoe off to make a last-minute check with Ken Adkisson, a conservation officer stationed at O'Neill. He assured me he would drop our camp gear at a slough about five miles downstream.

"You can't miss the spot," Ken assured me. "There's a point that sticks out "into the river with a grove of dead cottonwoods on it. Just pull in NEBRASKAland below the point and walk a few yards through the willows and you will hit the slough. I hope your bowman can read the river, or you might be doing a lot of pushing and pulling over the sandbars."

The bowman was my 14-year-old son, Paul, who was getting his initiation in canoeing. Our float trip had been suggested by Ken, and all of us were enthusiastic about it. The Niobrara, which begins in Wyoming, is a changeable river. It is a small, meandering trout stream at the headwaters, but by the time it reaches the canyons southwest of Valentine it becomes one of the most picturesque rivers in Nebraska. The canyon walls are covered with cedar and Ponderosa pine and cut a rugged swath for more than a hundred miles through the northern Sand Hills.

Once free of the canyons, the Niobrara widens out, creating many sloughs and bayous. These cutoffs provided a better environment for fish than the river itself, and most of them support catfish, carp, bass, and bluegill. We intended to sample the fishing, but the float was more of a summer adventure than a hardnosed fishing expedition. We planned to float from the Nebraska Highway 11 bridge, north of Atkinson, to Spencer Dam. Moments after we pushed away, we floated under the bridge and followed Lee and Don along the north bank of the river. Our canoe, like theirs, was a 16-foot aluminum job.

A mile below the bridge, we saw what looked like a slough, but a brief check showed that it was mostly vegetation and not very promising for fishing. Here, the channel cut across to the south bank, and we made a game of trying to pick the deeper runs to get across the 200-yard-wide river.

"Reminds me of the saying about the Platte River," I said as we slid the canoes through an inch of water, ' a mile wide and an inch deep."

Nearing the south shore, we spotted the opening to another slough, so Lee hiked across a hundred yards of sandbar to check it out. He was back in 15 minutes, saying it was a cutoff and pretty muddy.

"Might be OK. for cats," Don offered, "but all we have are artificials and they won't take many catfish."

"Let's find one where I can catch a bigger bass than my dad," Paul injected. "Besides I think this canoeing is more fun than fishing, anyway."

"I'm in agreement, Paul," Lee answered. "This canoeing sure beats running the cheese factory back in O'Neill."

MAY 1970"Or running a motel in Spencer," Don chimed in. "How about you, Dad," Paul quizzed with a grin. 'What are you running away from?"

"The profundity of that interrogative expression, young man, leaves me with an indubitable answer," I said, responding to the obvious ribbing. "If it were not for the pen and camera, we might all be laboring today at some menial tasks."

"Boy," Paul shot back, "if you guys think that's bad, you should ask him how to take a picture."

Hugging the south bank, we floated downriver looking for some fishable cutoffs. A number of small ones, overgrown by bulrushes and fringed with willow were passed up as too shallow for fishing. They did, however, reveal the important part they played in the wildlife community along the river. Muskrats snaked through the rushes, gathering roots and plants for food and home repair. A beaver slapped his tail in alarm at our approach to his dam and a pair of wood ducks zipped in from another cutoff, emitting their squealing calls.

We rounded a bend some four miles downstream from the bridge and found what we were looking for. The slough was cut off from the river by a narrow sandbar less than 10-feet wide and looked to be a good 100 yards long. As we pulled the canoes over the bar, a couple of fish scooted out of the shallows and headed up the slough.

"At least there are fish in it," Don said as he rigged his spinning outfit.

"Those were probably carp," Lee offered. "What lure should we try first?"

"A plastic crawler wouldn't be bad," I suggested. "A surface plug might get results, too, seeing the day's somewhat overcast."

"The water is a little turbid," Lee observed. "We'll have to work it pretty slow, but it sure looks fishy to me."

Keeping the canoes along the north shore out of the light wind, we cast about (Continued on page 62)

15

Inshata Theumba - - BRIGHT EYES

Two ways of life lived in her. Born in the days of earth lodges, she walked along both Indian and white paths throughout all the days of her life

Photographs courtesy Nebraska State Historical SocietyTHE ANGUISH OF her lost generation lived in her. The heart of a culture died with her parents, and they had nothing to teach their children except the courage to live. She knew what it was to be different and she became a symbol of that difference. Her name was Inshata Theumba, Bright Eyes. She was the daughter of an Omaha chief.

Bright Eyes was the second-born of Joseph and Mary La Flesche. Her father was the son of a French trapper, Joseph La Flesche, and an Indian, Wa-tun-na. Her mother was the daughter of an Army surgeon, John Gale, and an Indian woman, Ni-co-mi.

Longfellow once called her Minnehaha, years after his "Hiawatha," for she was the embodiment of his beautiful Indian maid. But she was also a talented young woman who felt the tragedy of her people and who communicated it to thousands of whites.

Bright Eyes, or Susette La Flesche, spent her youth divided between two worlds. Her father was the last Omaha chief appointed under the old rites, but he sincerely believed that the only path to salvation for the Indians was acceptance of white culture. But how should they change? The family wavered in uncertainty.

Susette began life in the Indian way. Born in the days of the earth lodge, she spent her infancy with tribal customs. To some degree she walked tribal paths until she was 20. From then on she developed more and more white customs.

A tender people, the Indians taught their children the art of giving. Among them, a man's worth was measured by what he gave away, not by what he had. Open handed and open hearted, these people gave away everything in their tents, never fearing for tomorrow. Their neighbors would surely give them whatever they might need —until their tents were bare. They had a security unknown to whites, a security of all-encompassing good fellowship.

Susette learned the dignity of giving, and the bounty of the buffalo hunt. But she was born in 1854, before the days of the reservation. While her early childhood was thoroughly Indian, it soon became evident that the old ways could not survive. The encroachment of the whites on Indian territories was destroying the objects of life.

Year by year buffalo hunts failed. And as they did, the old religion failed. Without buffalo, there were no sacred objects to renew the success of the hunt. Without ceremonies to please the gods, the people despaired of regaining their favor. Hunger walked the village. The very objects of life were (Continued on page 53)

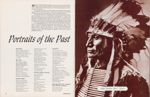

Portraits of the Past

WORLD EXPOSITIONS ARE few and far between in Nebraska. But the state did pull off one of the most extravagant on record in 1898 when Omaha hosted the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition.

Among other attractions at the affair were Indians representing some 26 North American tribes. And, while all physical reminders of Expo '98 are gone, reminders of its noble red guests remain.

Among the millions of spectators that passed through the exposition's portals was one F. A. Rinehart, photographer. To him, the faces of the Indians represented the way of a people — a way that was doomed. But photographer Rinehart held the key to preservation. He began recording the Indians on glass photographic plates and went beyond the exposition to photograph notable Indians until 1900.

Now, his collection rests with the Rinehart-Marsden Studio in Omaha. NEBRASKAland proudly presents portions of that collection, courtesy of Rinehart-Marsden. Accompanying poetry is of Indian origin — written by Frank V. Love of the First Reformed Church of the Omaha Indian Mission at Macy. This is the first of a two-part series with the second to appear in the June issue of NEBRASKAland.

PRAYER When a white man prays I listen with my head desiring to know what he means and if he really means it. When an Indian prays I cry because he touches my heart. MY SON You came so small Into so large a world So full of life, death Will your little eyes see Great men fall Countries rise Walls of color breaking My son, when we leave This life may Our way continue to Express one who also Came as a son of man To renew, remake, redeem. SNOW BANK She was an old lady kissing a stray, yellow and white alley cat, on California Street by the Local Laborer's Hall in Omaha Soon she got in her sack and fed the cat Her old black coat was unbuttoned as she stood in the snow that February day The city's five o'clock traffic was moving home and she began to wave at the passing cars Her faded scarf hung loosely about her white head, while she waved hello or good-bye (I don't know which) I thought of all the kind things I could do for this old lady... But it was five o'clock so with the traffic I went home too. TOUGH JOHN WAYNE One shot and six Indians fell from their ponies Little Bear the strongest warrior of all was hiding behind a big rock and he fell down, too Man, that big bad and tough John Wayne sure can shoot Where was he at when Custer needed him! DIGNITY Let the word go out from the Seneca in the East from the Sioux in the North from the Kiowa in the South from the Apache in the West to the blue-eyes who wear the long knives You take our land and fill yourselves full with fat barns and lokg fences kill, steal, and convert to get it But like the earth mother, my mother the sunshine, my father the four winds, my brothers and the four seasons, my sisters and all the animals, my relatives everything that grows, my friends These you cannot have you cannot kill, steal, or convert them These you cannot have and my dignity. REFLECTION ON A MEAN OLD WHITE WOMAN "She looks like she got in an axe fight and they forgot to give her an axe."

ONCE UPON A RANCH

You can see the West from "inside out" at a real Nebraska "spread". Street lights and cares are forgotten when playing in the scenic outdoors

OVER A CENTURY ago, electrifying journalist Horace Greeley raised a clenched fist and said, "Go West, young man". Today the opportunity to "Go West" remains a reality in NEBRASKAland. Travelers here find room to roam, to see, and to do. And, to see the West from the "inside out", visitors may choose to spend time at one of several vacation ranches scattered about Nebraska, including Rimrock Recreation Ranch nestled in western Nebraska's picturesque Pine Ridge.

Implementing the principle that there's more than one way to take a vacation, Rimrock Ranch owner Ross Raum set aside a portion of his scenic-rich ranch some seven years ago and began developing the area into a ranch-type resort. In the past seven years five fully modern cabins have blossomed on the grounds. Nearly everything else about Rimrock Ranch came with Raum's original deed to the property. Majestic buttes and pinnacles of the Pine Ridge tower toward the skies as the Great Plains rise to meet the Rocky Mountains. Stately pine trees march up and down the hills where such immortal figures as Crazy Horse and Custer once strode. A massive rim of cragged bluffs perimeters the restful area lending the ranch its name —Rimrock.

27 Editor's Note: Rimrock Recreation Ranch, located nine miles northwest of Crawford,

is but one of many vacation ranches that have sprung up in Nebraska the past few years

as cowmen roll out the welcome mat and turn hosts to meet a rapidly growing

vacation demand. For a complete listing of Nebraska ranch vacations and boys' and

girls' recreation camps, turn to page 61

Editor's Note: Rimrock Recreation Ranch, located nine miles northwest of Crawford,

is but one of many vacation ranches that have sprung up in Nebraska the past few years

as cowmen roll out the welcome mat and turn hosts to meet a rapidly growing

vacation demand. For a complete listing of Nebraska ranch vacations and boys' and

girls' recreation camps, turn to page 61

Although tucked away in Mother Nature's silent beauty of the real West, Rimrock Ranch is as isolated and sedate or as lively and rollicking as the individual vacationer wishes. The ranch boasts near-fantastic bass and trout fishing, offering angling buffs their choice from any of five spring-fed ponds. Toadstool Park, historic Fort Robinson, the Museum of the Fur Trade, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Chadron State Park, and Nebraska's best offering grounds of Indian artifacts and fossils are all within a few minutes' drive. The state's rugged Badlands are also nearby to challenge and mystify seasoned scientists and adventuring travelers alike. Supervised horseback rides and unlimited hiking and photography opportunities are at every visitor's command at Rimrock. And, as autumn encroaches on the land, big-game hunting enthusiasts find their mecca here, as deer and wild turkey roam the countryside and antelope abound close-by.

Cabin facilities at Rimrock are an enticement for anyone wanting to take a step backwards into the past and see how "it might have been", as the buildings resemble log cabins of old. Telephones and radios have purposely been omitted from the lodgings to allow complete escape from everyday routine. Visitors move into the housekeeping units with only food and clothing as necessary equipment. All kitchen utensils and bedding are provided. Folks are on their own to do whatever they please or, more contemporarily said, "to do their own thing". A Rimrock Ranch vacation functions strictly on any easygoing, do-as-you-like basis. There is no ranch work and visitors create their own activities on a schedule as jam-packed or leisurely as desired. Some Nebraska ranch vacations are the "working" type, where the visitor can pitch in and be an "honest-to-West" cowboy during his stay.

Sightseeing and hiking are Rimrock's strongest suits and are as natural as country life itself. The opportunity to "move-in" with such a scenic environment and "drop-out" of the day-to-day scuffle of urban life attracts the majority of Rimrock's vacationers.

"The idea of the ranch vacation might seem somewhat limited to the prospective visitor at first glance," according to Larry Lanphier, Sr.; of Omaha. "But quite to the contrary, the see-and-do (Continued on page 60)

28

CASE FOR FLIES

When bluegills show their "dimples", it's stringer-filling time for fisherman who knows how to use super-light rod

A SMALL GRAY mayfly landed gently on the pond and busily stroked his head with his forelegs. The slight motion sent tiny ripples radiating from the insect's resting place. As the fly shimmered on the surface, a slab-sided bluegill darted from his hiding place under the bank and momentarily hung beneath his unsuspecting victim. With a sudden flare of his gills, the fish sucked in the fly. Satisfied for the moment, the bluegill flipped his tail and glided back to his haunt.

The fish hovered there for a short time before another fly of approximately the same size, shape, and color touched down on the surface. A slight twitching of the fly's legs alerted the bluegill and he repeated his stalk. Again he glided silently under the fly, inspected it, and then inhaled it. This time when the bluegill retreated to the shelter of the bank, a sharp tug jerked him back. Panicky now, the fish fought desperately to gain his hiding place but the pressure was relentless.

Darting from side-to-side, the bluegill made a run for the weed-covered bottom of the pond, but the strong

My five-year-old son, Jamie, slipped a small thumb into the fish's mouth and lifted him high. He beamed at his fish and then at me when I complimented him on his catch.

The occasion was one of our frequent evening fishing trips to a small farm pond just a few minutes' drive from our home in southeast Lincoln. Before our expedition ended Jamie caught seven more bluegill and missed at least a dozen others. My son and I are both addicted to fishing and we make two or three trips each week plus spending the lion's share of our weekends chasing fish somewhere in the state.

Jamie was generally a cane-pole man because of the knots and tangles which result from his frantic reeling when he gets a bite. But, after a week or so of constant pleading, begging, and complaining about how the fish ignored his worms while I was taking them on flies, I finally made him a small fly rod. With his rod and some of my home-tied flies he has since accounted for a heap of bluegill and small bass.

Fly-fishing is probably the most underrated form of fishing in eastern Nebraska. Most people believe the terms, "fly-fishing" and "trout fishing", are synonymous and therefore conclude that fly casting should be limited to trout waters. Fly-fishermen do account for a lot of trout, but they also take healthy amounts of panfish, bass, and northern pike with their artificials.

An afternoon or evening spent on a panfish and bass-rich pond or stream will convince anyone that here is one of the most exciting methods of catching NEBRASKAland

There is a popular myth that fly casting is exceedingly difficult to master. Nonsense. Five-year-old Jamie learned to cast well enough in an hour to regularly catch fish. His style and form are far from perfect, but he gets results.

To enjoy some memorable fishing that can fill an iron skillet in a hurry, plan to be at the edge of a pond or lake early on a warm evening. Watch the water for signs of feeding fish. Surface dimples and jumping fish are good clues.

Use a small fly, from 12 to 16, in one of the standard patterns (the "royal coachman" is usually good) and cast to the immediate area of the feeding fish. Allow the fly to touch down lightly, then twitch it ever so gently.

A flash of color where your fly landed, a dimple in the water, small ripples where the fly was, or a sharp tug on your line signal a strike. Set the hook gently and enjoy the quick runs and flips as the three-quarters-pound of energy on the business end of the line fights the hook. Small fish seem large and the big ones feel like tackle busters on a fly rod.

There is a certain elation when a fish is taken on a super-light rod and a fly you have tied yourself. Any fish is a thrill to catch on a fly rod, and when an occasional bass slams the light rig the fun really begins.

My own recipe for a great afternoon of fishing includes a good friend for a fishing partner, a fly box full of my own creations, a farm pond, and a few scrappy fish. Throw in some clear water, a warm spring day, a few sandwiches and some coffee and mix well. With these ingredients in the proper proportions, you can't go wrong.

Ken Ideen, a fishing and fly-tying buddy of mine and I started taking my son with us as soon as he was big enough to walk. We soon found that a small boy becomes bored rather quickly with fishing, if he has to sit for long periods with nothing to do but stare at a bobber. That's the beauty of bluegill for they are action fish. If you have a youngster along, locate a school of bluegill for him. He won't have time to be bored.

For my farm-pond fly-fishing, I use a lightweight seven-foot rod, floating line, and a leader testing about two pounds. Poppers, wet and dry flies, streamers, bucktails, and hair bugs are my standbys. I tie my own flies and bugs, but I buy the poppers.

Any Nebraskan can enjoy fly-fishing for panfish and bass at almost any time the notion strikes him. Here in southeast sections of the state, we have easy access to the Salt Valley lakes. I do much of my fishing in these numerous lakes and my fly rod has accounted for perch, bluegill, crappie, northern pike, and large-mouth bass. The small panfish prefer tiny poppers and small wet and dry flies. Bass go for deer-hair bugs, larger flies, and poppers. Northerns will smash large bucktails and streamers.

So, treat yourself to a new method of fishing —one I'll guarantee you'll enjoy. THE END

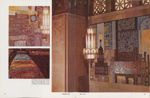

WONDER OF THE WORLD

Part two continues searching the State Capitol for beauties which often escape the hurried visitor

IT'S A CAPITAL place to visit and sightseers with an eye for the unusual and oft-missed detail will revel in the delights to be found in the halls and chambers of Nebraska's State Capitol.

NEBRASKAland cameras again focus on the little-noticed, yet fascinating "little things" that combine to make this statehouse one of the architectural wonders of the world.

Each visit to this intriguing building will reveal still another intricate, geometric pattern or enchanting aspect that was overlooked the last time around. The next few pages disclose but a few of the minute features that await discovery.

This is just an appetizer. The main course requires personal attention.

32

EUTROPHICATION

42 NEBRASKAland 1970Lakes don't always age gracefully, but humans cause most of growing pains

FOR CENTURIES, MAN has been changing, often destroying, his environment. But recently, words like "ecology" and "pollution" have been creeping into household vocabularies in Nebraska and across the nation. Now, another word — eutrophication — has taken on added importance, for in Nebraska it can become a major problem.

Eutrophication is the process by which lakes age. When a lake is born, it contains scant nutrients and is biologically unproductive. Aquatic life simply does not become abundant in these waters. Eutrophication is the answer — provided it is not carried too far.

The process begins as nutrients flow into the lake from surrounding land or are deposited by water birds or are borne to the lake by wind and rain. With the added nutrients, the lake becomes more productive and eventually is capable of sustaining an abundant biological community.

When a lake is productive, organic matter from dead plants and animals forms deposits on the lake bottom and it is slowly but surely filled. Also, sand and organic matter from the watershed will contribute to the aging process. As this process goes on, the lake becomes a swamp —then a meadow. Unless man interferes, it requires many thousands of years to fill most mountain lakes. However, when lakes are formed in fertile prairie land, this natural process is much more rapid. Lakes in such areas can begin in a eutrophic condition — able to sustain abundant life at their birth. In such a case, the life of the lake is very short.

Eutrophication is both beneficial and detrimental to man's interest. Highly eutrophic conditions in the dim past led to the great coal and oil fields which have created man's modern way of life. More currently, eutrophic lakes provided man with abundant fish and waterfowl. Few fishermen would want to fish an oligotrophy lake — one without nutrients — located where it could be heavily fished. Although often beautiful, such lakes could not sustain heavy fishing pressure.

On highly eutrophic lakes, harm to even one use of the lake is cause for concern. Just as abundant nitrogen and phosphorus are required for luxuriant lawn and crop growth, so are they needed for luxuriant growth of algae and aquatic plants.

In North America, lawns and crops are well fertilized. With rainfall and irrigation runoff, these major nutrients, along with minor ones in the soil, are washed into natural waterways and lakes. Add tremendous amounts of domestic sewage - doubly rich in phosphorus because of common detergent use — industrial sewage and cattle feedlot runoff, and you have some picture of cultural eutrophication. These sources of nutrients carry with them another important ingredient for accelerated aquatic growth — organic matter. Bacterial action on this matter releases more carbon dixode than any other source. With such mineral abundance, sunlight, and warm temperatures, the stage is set for a population explosion of blue-green algae and other aquatic plants.

In an agricultural state such as Nebraska, there is little which can be done now to solve the problem. As little as 0.4 ounces of phosphorus per acre-foot of water is enough to cause excessive growth. More than this is readily supplied by fertilizers used on Nebraska MAY 1970 cropland. And, there is no technique for controlling nutrients entering waters from agricultural sources. On the other hand, it is possible to remove most of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic matter from domestic and industrial wastes. Although not solving the problem, this would tend to alleviate it. But, such treatment would skyrocket the price Nebraskans now pay for waste treatment. The logical solution to cultural eutrophication is never to allow our waste material to enter water systems — an unlikely remedy in the near future.

Other measures have been suggested, but these are no more than stopgap measures and are rarely economically feasible. Among them are chemical treatment to kill both algae and rooted aquatics, and mechanical cutting of rooted aquatic plants. Both measures are only temporary and are very expensive. Cutting must be done two or three times a season to be effective and, because of the expense has been limited to clearing swimming beaches, areas near boat docks, and navigation routes. Finding a commercial use for cut vegetation might lower the cost and lead to more extensive use of the system, however. Chemicals have the added disadvantage of possibly contaminating the environment.

Fortunately, Nebraska has abundant ground water and most of our domestic water comes from that source. The uses most frequently made of our surface waters are recreation and irrigation. In irrigation waters, eutrophication creates few problems. But, many forms of recreation can be hindred by highly eutrophic water.

Boating can be restricted by beds of rooted aquatic plants or filamentous algae. Also, if the degree of eutrophy is high, the lake is not as attractive and boating pleasure is reduced. Swimming also suffers. However, where swimming is allowed in state lakes, it is restricted to designated areas and these areas are kept clear of aquatic plants.

Swimmers, boaters, and fishermen can all make use of many of our lakes at once, but some zoning is required. Pleasure boaters are prevented from using much of the shallow and often weed-clogged portions of lakes. Although fishermen share much of the multiple-use lakes with pleasure boaters, they realize there may be some annoyances when fishing areas are open to pleasure boating.

Fishermen are by far the greatest users of our lakes. They are sometimes inconvenienced by vegetation close to shore. When the lake is banded by vegetation and beds of vegetation extend well into the lake, bank fishing is severely hampered and the quality of fish in the lake is also in danger. With such extensive vegetation, many small fish are protected from predators. What usually occurs is an overpopulation of forage species such as bluegill and a consequent decrease in average fish size. When this happens, there are large numbers of three-to-five-inch fish waiting in weed beds to prey upon the fry and fingerlings of more sought-after predator fish. But perhaps more importantly, these large numbers of forage species compete with the fingerlings of the predator species for food.

However, most of Nebraska's native fish are well adapted to eutrophic conditions. Thus, if a superabundance of forage fish can be avoided, we can expect good fishing. In this we are fortunate, for even with massive effort, many years will be required for effective control of nutrients entering lakes from agricultural lands. And in the meantime, Nebraska can continue to provide its broad range of water sports. THE END

43

List of accomplishments grows as state plucks plum of fun on wheels

WORLD SERIES OF ROLLER SKATING

NEBRASKA HAS LONG been known as the mixed-bag capital, but in August the state can claim another impressive title, the Roller Skating Capital of the nation.

During August, first the North American Roller Skating Championships, then the World Championships will be held in Lincoln. Nebraskans have watched the North American competition twice before, but when the World Championships move into the Capital City, August 13 through 17, it will be a first for both Nebraska and the United States. The 14 previous World meets have been held in various places around the globe, but until this year they have never come to the United States.

The World Championships, held every two years, are expected to draw skaters from nearly 30 foreign countries. When Lincoln was selected as the site, the town was competing with such cities as Miami Beach, Florida. Directors of the meet felt Nebraska and its first city were the images of America they wanted visiting skaters to see. Besides, Lincoln's experience in handling two previous North American Championships made it an odds-on favorite.

However, hosting the World Championships isn't enough to make Nebraska the nation's Roller Skating Capital. Backing up its claim is the fact that the national offices for the Roller Skating Rink Operators Association (RSROA) are in Lincoln, the North American Championships have been held here, and Omaha's Skateland Skate Center presently ranks as one of the top facilities, attendance wise, in the nation. In addition, three nearly new rinks are open in the state, one each in Lincoln, Omaha, and Grand Island, and two more are in the works for Omaha.

But skating is more than a spectator sport to Nebraskans. In many high school crowds it's the "in" thing to do on a Friday date. To church groups it is a wholesome and healthy form of recreation, while for the Girl Scouts it means earning a merit badge.

Skating has grown tremendously in the last five years in Nebraska. It takes only one trip to the state's newest rink to understand why. The ultra-modern skating center was shrouded in a misty fog on a cold Sunday night in February. For most, it was a perfect night to stay at home. But nearly 300 people braved slippery roads for a three-hour session at the Holiday Skating Center in Lincoln.

Family night at the rink, the sounds were active and full of laughter. Ron Jeru stood in front of a sound system that looked like it belonged in a radio station. As he announced that the next group of songs was for partner's choice skating, the rink lights faded to a soft blue.

"Skating has come into its own in the last few years," the rink manager said as he watched couples glide around the big floor. "Our biggest problem right now is combating the bad image many people have of roller skating. In the past, rinks were considered the local hangout for hoods."

Skating was a favorite pastime during World War II. Ma and Pa rinks, skating facilities run by usually just two people, sprang up in basements, old garages, and other buildings. The sport was popular because it was an inexpensive way to have a good time. After the war, bowling and other family sports began grabbing the recreation dollars. When other recreations began to modernize their plants and cater to family-type recreation, many rink operators were content to sit back and (Continued on page 64)

MAY 1970 45

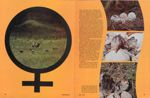

28 DAYS TO TURKEY

Chicken or egg theory gets new slant as state's gobblers dramatize the miracle of life

THE AGE-OLD ADAGE of "Which Came First, the Bird or the Egg" is easily answered, at least when discussing the Merriam's wild turkey in Nebraska. It was definitely the turkey.

During the winter of 1958-59, 28 wild trapped birds were released at two sites in the Pine Ridge. From the original 28 birds, an estimated population of 5,000 turkeys roamed the Ponderosa pine-studded hills of northwest Nebraska in a few short years. Additional transplants from this flock were made in several areas of the state with varying degrees of success.

The mating activity of the wild turkey normally commences in March with the torn gobbling and strutting. The date and amount of activity is generally related to weather, with increased sunlight hours affecting the reproductive system. The torn, being polygamous, attempts to lure several females to his area. A gobbler usually attempts to fight any male that intrudes into his area, especially early in the season. A torn may lure as many as eight hens to an area and there he displays and gobbles in an attempt to entice the hens. The brilliant color, actions, and gobbling of the torn turkey during mating season are an unforgettable experience.

Hens spend a considerable amount of time with the gobbler during the early mating season, especially during the 46 NEBRASKAland

The turkey nest is usually a crude depression in the ground, rather well hidden, and is lined with pine needles, leaves, or twigs. The average clutch size is about 12 eggs and requires the hen approximately two weeks to complete. Upon completion of the clutch the hen may not begin incubation immediately, but usually does within a day or two. She normally remains on the nest until completion of the incubation period, except to leave for short periods to feed and water. Toward the end of incubation, feeding and watering are at a minimum and the hen may not leave the nest for several days just prior to hatching.

Embryonic development is one of nature's amazing processes, and very little is known about the true wild turkey embryo development. Therefore, studies are conducted on domestic or game-farm birds to obtain this information. The incubation period for the turkey is 28 days, compared to 26 days for the mallard duck and 21 days for the domestic chicken.

Embryo development starts immediately after the hen sets on the eggs for a prolonged period. Development begins for all eggs at the same time, therefore all eggs that are going to hatch do so within 24 hours after completion of incubation.

Within 24 hours of incubation a thin, barely visible line is formed. This line is called the primitive streak and is the origin (Continued on page 59)

SACRAMENTO MIXED BAG

A state area in south-central Nebraska is target of a hunt to sample its game potential

DUCKS FILLED THE sky, their criss-crossing 1 patterns forming a huge, black mesh against the lightening east. Milling in all directions and at all levels, the flocks saturated the air with a wierd whistling like no other sound.

Our hunting party moved single file through the tall weeds as we started our mixed-bag hunt at the Sacramento Game Management Area in south-central Nebraska. The aerial activity above us became even more impressive as the sun inched upward to the horizon. We headed for the middle of the lagoon, with me, carrying a bulging bag of decoys, bringing up the rear. Water was lapping at the tops of my rubber boots as we sprinkled the decoys on an open patch of water. Then we formed two groups and crouched in the heaviest reeds we could find.

Our casual sloshing through the field had not gone unnoticed by the ducks. In fact, they were all settling into the marsh about the same time we were —only they were some distance away. Within a few minutes the sky traffic diminished remarkably, but there were still plenty of scattered formations moving about. Evald Abrahamson, a Holdrege appliance dealer, absolutely bristled with efficiency as we settled into the lagoon. He selected one of the three duck calls which 50 NEBRASKAland

I wasn't gunning, so I had a ringside seat for the action. Some faraway ducks looked like fly specks on the blue canopy of sky, but Evald quacked and squawked and chattered on his call. At first nothing happened, then the specks turned and became larger. The first time, I thought it was only coincidence that the webfeet searched us out. But as Evald diverted flock after flock from whatever they were thinking of doing I realized they were hearing and heeding Evald s "call of the wild duck".

Dick Person, an attorney from Holdrege, occasionally chimed in with a few squawks, but the rest of us accused him of talking "foul" language, so he gave up and concentrated on spotting and shooting. Orval Harms, administrator of Brewster Hospital in Holdrege, was the third hunter in the group. I was there from NEBRASKAland Magazine to do a story, while Richard Voges our photographer, was shooting only on film.

Our hunt had its inception at NEBRASKAland's headquarters in Lincoln two weeks before. The idea was to hunt out a state area to see what kind of mixed-bag success would result. The Sacramento State Special Use Area near Wilcox was chosen, and I was MAY 1970 assigned the story since I had lived a scant 10 miles from Sacramento, for 7 years.

Several friends of mine agreed to take part in the two-day project, and November 22 was chosen as the starting date. That was just one week after the start of the second half of the 1968 split season on ducks, and nearly three weeks after the pheasant and quail seasons opened. Our hunt started with ducks.

The weather was almost too nice for duck hunting, yet things were really popping. Evald kept teasing singles and flocks into 12-gauge range, but even when the ducks winged over too high, Evald's big Labrador, Jet, and I got excited. Whenever the gunners fired, Jet was ready to dash for a downed duck. He made that dash five times in about an hour and a half as the three hunters stoned five mallard drakes.

Five was one short of the three-hunter limit, but the duck traffic was slowing, so we decided to knock off and look for other game. My boots had taken in water while I was scrunched up in the makeshift blind, but wet feet didn't really matter with temperatures in the high 50's.

After a little good-humored joshing about Evald's

near-antique 12-gauge pump gun and the snapping of

a few photos, we planned our strategy for the rest of

51

There are a couple patches we had better walk out later," Orval predicted, pointing to some prime brushy plots. He had hunted the area many times and was familiar with its best spots.

Minutes after our return from lunch we bagged twq pheasants. Orval scored first with a clean shot frofh his full-choked 12-gauge slide-action. His bird went up just after we stepped into a small area between an interior road and a shelterbelt. The second rooster zoomed up and was over the trees when Dick Person connected with his fancy 12-gauge autoloader. To retrieve his bird, we had to get through the trees, and that turned into a chore. Sharp spines of the stickery foliage put up a fight like the enchanted forest. Luckily, the rooster was down for the count, or he would have run for three miles while we fought and bled through that grove.

We got back into the open just in time to see more than a dozen hens exit from the corner plot. A few minutes later, some cocks flushed so far away they were nearly out of sight. All of the birds flew toward the marsh, and most went into the refuge portion.

'They know where they're safe," someone remarked.

A third ringneck joined our growing supply of game as Dick and I, accompanied by his Irish setter, Kelly, walked out some dense cover near the south 52 border road. It was a picturesque shot. The rooster got up only 25 feet in front of Dick, angled away at top speed, and dropped cleanly with his first shot. Kelly was right on the ball to recover the gaudy bird.

'That was neatly done," I told Dick as Kelly proudly handed him his pheasant. "You guys are doing just fine, three birds for three shots."

It doesn't pay to pat yourself on the back too soon, for those three birds were nearly the last of what we got, although we saw a great many.

While we were walking out the patch by the road, Orval had cut across country and was cornering a fox squirrel when we rejoined him. Using "Kentucky leverage", I waited on the opposite side of the tree as the bushy tail came around to hide from Orval, then I gunned him.

"You could have just jumped up and down and that squirrel would have run around to my side," Orval charged, empty-handed after the cautious stalk.

I accused him of already having half the fun by locating the game, but he just scowled. We moved away to walk out a field, working toward a draw that separated it from an adjacent cornfield. Our plan was pretty good but there was too much yardage between us. Pheasants kept getting up at the far right of the line and cutting diagonally across, but too far out. We didn't get much shooting, and those we did shoot at never knew it, for we didn't cut a feather. If the birds had been less wary, we could have limited out right there if we could have hit them.

As it was, we spent the afternoon stomping fields and forest, but only one more pheasant went into the larder. I lucked onto him near the end of a large, terraced field, and my autoloader dumped him with one shot. Moments later, two bunnies became destined for the stewpot when their fancy footwork failed to keep them out of trouble. I scragged one just moments after the ringneck fell, and Dick clobbered the other in the openings between the trees of a large shelterbelt.

We jumped some bob whites near the end of that same shelterbelt, but they cut back in before anyone had a clear shot, and we never kicked them up again. All in all, the afternoon hunt had been quite successful, and we returned to town tired but satisfied with our day.

An early start was on the agenda for our second day, and Bob Harris, a former Holdregeite who now lives in Hastings where he works for a utilities company, joined our crew. Evald Abrahamson returned for another go at the ducks in the morning, so we had a capable group counting Orval and Dick. Photographer Voges and I watched from a dugout on the side of a big dike which cuts through the marshland, while the hunters waded out into the rushes.

Apparently the late-fall hot streak was catching up with the ducks. Where there had been literally thousands the day before, there were only hundreds now. They might have been sitting tight, or using the good weather to make trails to the south, but in either case, they were not hovering overhead.

Evald managed to call in a few, but it was generally tough going. The contrast with the day before was remarkable, yet even with the vast reduction in ducks, Orval got two.

"I got my limit just because you didn't see me get any yesterday," Orval shouted during a lull in activity.

Attorney Dick Person had to take care of some business in town, so I decided to walk out with him.

We had just reached a cleared levee leading back to the road, when a lone mallard drake skittered off a pond. The attorney's shotgun came up and swung with the rising duck. He fired and the shot pattern dimpled the pond's surface beyond. The (Continued on page 64)

NEBRASKAlandBRIGHT EYES

(Continued from page 17)stripped from a people as their old buffalo robes wore out without replacements. They were given provisions by the government, but never nearly enough. Women, who had always been busy processing hides, and meat, and sinews of the buffalo, were idle. The old men, who had mysteriously gone about the ceremonies of the tribe, sat half-sleeping. Their importance died with the huge buffalo herds. Idly they sat, trying to think of some way to regain the gods' favor. Sadly they watched young people growing up wild, without the refinements of old customs.

Joseph, known to the Indians as Iron Eye, declared in the midst of this chaos that the Indian way was dying and his people must learn the way of the white. The Omaha must forget the old and learn to cope with an entirely new world. They must learn to till the soil, and build permanent frame houses, and live in one place. They must stop following the dwindling buffalo herds.

While the old men laughed, Joseph led his young men's party in building a "make-believe white man's village." In the early days of the reservation, while buffalo hunts were still a part of their lives, the Indians couldn't understand his insistence on imitating whites. But gradually, old leaders lost their ability to lead. The despairing tribe turned to the young men's party and to Joseph.

Iron Eye tried to learn English, and he adopted the white man's religion. Many followed him. He sent his children to the mission school — many other Indians did, too. Several times in the early days of the reservation, Iron Eye stayed home from the hunts, trying to show the people that they must learn new ways.

He denied his daughters the tribal right to wear the mark of honor. The mark was a tattoo on the forehead and neck of daughters of honored members of the tribe, men with many good deeds to their credit. Joseph was such a man. The time when Susette would have received the mark was a time of trouble for the La Flesche family, and Joseph refused it.

As he gradually took on the white man's ways, Joseph's children were forced to watch him disgraced before the tribe. Greedy white settlers fostered misunderstandings that were damaging to Iron Eye's reputation among tribesmen. He was accused of arranging tribal matters for his own profit. Finally, scandal resulted in the dismissal of the missionary who had taken an interest in Joseph, and in the Indian's discrediting. At last, Iron Eye "packed up his household goods and left."

He later returned, however. His children returned to school where all were educated. All but one went East to finish their education. Susette was the first to leave the reservation. Her opportunity came after the mission school closed. One of her former teachers, alert to her needs, asked what she would like to have for Christmas one year. Susette told him — more education.

The teacher had relatives in the East who were connected with a school for girls. After much planning and money gathering, Susette went East to school.

After nearly six years in the East, Susette was not prepared for her return to the reservation. Some of the things she learned made adjustment to the reservation nearly impossible. There was still no school, and it was hard to be content with the combination housekeeping her mother, Mary, had made from both Indian and white ways.

She had an opportunity to teach in the Indian Territory in Oklahoma, but still she was held by tradition. Her uncle by adoption, Two Crows, refused permission. By Indian custom, he had equal authority with her parents.

She later learned Indians were given preference in teaching Indian schools. And after extended red tape she was hired to reopen the Omaha reservation school. It wasn't until the Ponca's tragic move to the Indian Territory though, that Susette finally found her role. Her service to her people reached its apex with Standing Bear's epic fight for freedom.