NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

April 1970 50 cents CAPITOL BEAUTY BY DESIGN A CRUSADER RETIRES SPRING ANGLING SUCCESS

Take a spin around NEBRASKAland

7th ANNUAL NEBRASKAland FOUNDATION TOUR

Join the "in" group this summer for a spin through the land of western heroes and legends. This five- day tour will take you to the land of Buffalo Bill for a full day at NEBRASKAland Days. Other highlights include visits to Fort Kearny State Historical Park, Johnson Lake, Fort McPherson National Cemetery, Front Street, Lake McConaughy, Scotts Bluff National Monument, Champion Mill, Swanson Reservoir, Massacre Canyon, George Norris' home, Harlan County Reservoir, Pioneer Village, Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer, and more. See the West as the pioneer never saw it —from the comfort of an air conditioned bus and bedding down in modern motels. Wagon master Charlie Chace will again guide the expedition. Just $110 covers all expenses, including transportation, meals, and lodging. Get your reservations in today to get acquainted with NEBRASKAland this summer! JUNE 17-21 / SEND RESERVATIONS TO: John Sanders, Auburn Newspapers-Auburn, NebraskaFor the Record ... THE PAST IS PROLOGUE

The past decade has been spent largely in planning and preparation — in laying the groundwork for Nebraska's wildlife management, park, outdoor recreation, and tourist-trade programs. The 70's will be the decade when most of this development is completed. A variety of projects was constructed in the 60's, but many more are scheduled for the future.

In wildlife management, a better and wider understanding of the factors that lead to the rise and fall of wildlife populations was a primary goal during the 60's. Unless we all learn to understand that inadequate environment is the principal limiting factor for most forms of desirable wildlife today, there is no chance to meet and solve our small-game problems. In fact, unless Man learns and thoroughly understands that all life on this earth is completely dependent on its environment, then Man himself has no more chance of escaping an eventual "crash decline" of his own species than does the snowshoe hare or the lemming!

The future will see big game increase in Nebraska, since our deer and antelope are still living at levels below the carrying capacity of their environment. On the other hand, the outlook for small game is not bright. Ground-dwelling species like pheasant, quail, and cottontail are presently as numerous as their environment permits, and I see little hope that their habitats will improve substantially in the future. True, we can help small-game species if we stop destroying permanent cover unnecessarily, but there is little hope that we can add significant acreage, because the landowner must use every acre he can in providing income from the farm. No reasonable person can object to that. My objection is to the destruction of permanent cover on acres not used for crops.

The outlook for fish and fishing is the most encouraging prospect of all. New and more desirable species are being added. In fact, most of Nebraska's fishing today depends on species that were not originally native to this state. But the big gain will come in new fish-producing waters. Every time a new reservoir is built it adds another unit to our array of "fish factories". Approximately 60 major reservoirs are scheduled for construction in the next 10 years.

Much essential land has been acquired for parks and recreation. While some new areas have been developed, most construction still lies ahead. Substantial and extensive work is scheduled in this field, and the 70's will see the completion of many of these projects. Nebraska made a belated start in developing tourist trade. Hence, it still has a long way to go before the state can realize its potential in this field. Most developments which will increase tourist trade are yet to come.

The social needs of Nebraskans for outdoor recreation have been studied carefully. Our "Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan" is based on this research, and projects have been designed to meet major needs. It is not feasible nor possible to meet all demands, but it is the plan to meet justifiable needs.

In our planning, Nebraska's need for parks and outdoor recreation outlets have been combined with the need to develop attractions for tourist trade, thus "killing two birds with one stone".

The economic objective is to develop an outdoor recreation and tourist-trade business in Nebraska that will gross at least $500 million annually. Studies indicate that this is well within reach, provided we invest the effort and funds necessary. Since substantial public expenditures must be made to meet our social needs, wisdom dictates that this investment in the better life be made profitable as well. Most of this half billion dollar annual revenue will come from outside the state.

The past is prologue. It is gone forever. It is valuable only because of what we have learned and what we have done to prepare for the future. Nebraska's potential in outdoor recreation and tourist trade is very good. Nebraskans have made a start in the long-term task of developing that potential. Realization is in your hands, dear reader. The future is yours, and the future will be whatever you make it.

Good luck and Godspeed.

APRIL 1970travel the safe Hi Lo way

WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM 3

...new Snyder Sheik Dune Buggy Bodies

After producing over 4,000 fiber glass automotive bodies you become an expert. Now, Snyder's have their own quality "better-built" dune bodies available in all popular colors and in metal flake, too. The Snyder Sheik has recessed headlights, improved dash panel and widefenders.BIG I NEBRASKAgram

an important fact about the great cornhusker state NEBRASKANS LIVE LONGER. THAN PEOPLE IN ANY OTRER STATE-Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

NEBRASKA AND ALASKA-"I was born in Garden County, Nebraska in a sod house. I lived there until I was married. My husband and I have lived in many places, but to me Nebraska will always be home. We are now living in Alaska on the Kenai Peninsula and the weather and snow is much like it was in western Nebraska when I was a child. Alaska is a great place and we have seen many interesting things. But Nebraska is where my heart is and when we retire we plan to make our home in Nebraska." -Paul DaMeta, Kenai, Alaska.

BETTER INSIGHT-"Through the thoughtfulness of my pen friend, I have* been receiving NEBRASKAland Magazine for a year. I should like to thank you for the very pleasant reading during the past 12 months. My family and I now have a better insight into one section of life in the United States."-Lorraine McClanghry, Wellington, New Zealand.

ARMCHAIR ADVENTURER - "I enjoyed the article on Danny Liska in the February NEBRASKAland. Upon completing it, I immediately reread the articles I have collected in the past about his adventures.

"I guess my interest stems from the fact that my hometown is in Knox County near Niobrara, but I am also one of those armchair adventurers. I have attended one of Danny's lectures and also recall seeing him on network television. Your article only whetted my appetite and I hope you will publish more stories on him. Please let your readers NEBRASKAland know when the book he is writing goes on sale.

"I have also saved a series of articles on Dr. and Mrs. James Maly of Fullerton. They worked in the Amazon jungle and they should get recognition through NEBRASKAland Magazine, too."-Mrs. Harry Schmidt, Minden.

GOOD HUNT-'Keith Treece and myself are from Albuquerque, New Mexico, and again we had a fine hunt in NEBRASKAland. We averaged a little over four pheasants a day, got several quail, and a rabbit during our hunt in the first week of December. We also found the pheasant population about the same as the previous years in southwestern and southcentral Nebraska.

"Both of us want to thank the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission for the hunter's packet that we receive each year. It helps us plan our hunting trip." — Mike O'Bryant, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

INTRODUCE SPORTS?-"At our house we read your magazine from cover to cover, and then refer to it again.

"We note with concern that you contemplate introducing sports. Don't spoil the magazine! Let the Nebraska University athletic department get their foot in the door and that's the end of NEBRASKAland as it is. It'll be Go, Go Big Red, football ballyhoo, and articles by and about Coach Devaney.

"The pioneer articles and pictures are great, let's have more." —E. Earl Roy, Lincoln.

MORE TO OFFER-"I appreciate NEBRASKAland, especially since Nebraska will always be home to me. I share it with many others like me. NEBRASKAland has far more to offer than just this. It is a wonderful way to show the charms and potential of the whole state. The series of pictures in Symphony of the Seasons was utterly delightful."-Deloris M. Van Houten, Grand Junction, Colorado.

FISH MOUNTING-"Could you inform me as to where the kits are available for mounting fish as stated in the article in the February 1970 NEBRASKAland?" — Dr. C. G. Gross, Cambridge.

Fish mounting kits may be obtained by writing Norman K. Meyer, 4783 North Bend Road, Cincinnati, Ohio 45211.— Editor.

NEBRASKA EXPERIENCES-"My brother has given me a subscription to NEBRASKAland and I enjoy reading the articles very much, but they make me homesick. In one Speak Up there was mention of a soddie, and that brings back memories. I have lived in four different Custer County soddies near Callaway. In the summer of 1914 I helped my father build a soddie and I think that was probably the last soddie built in the county.

"I also experienced a Nebraska tornado in 1916. It struck without warning in the afternoon. It lifted the roof of the soddie and dropped it back in the same spot. It raised so much dust we couldn't see for awhile.

"My little sister had been outdoors and mother ran out to protect her. Mother was cut by flying debris, but that was the only injury.

"Once when I was fishing on the South Loup near Oconto I experienced a cloudburst to beat all others. It washed my Ford several hundred yards down the river. All we found of it was the engine and chassis." —Carl Adams, Seattle, Washington.

TANTALIZING MEMORIES-"The Truth About Family Camping by Shirley Lueth proved to be a delightful story of their camping experience at Johnson Lake. In my case it brought back happy memories of fabulous crappie fishing which that man-made lake offered for a number of years after its construction.

The enclosed photo of our two sons was taken at Johnson Lake about 25 years ago. That stringer of crappies included the combined take of our two

"My aging parents lived in Beaver City at the time. Our annual spring visit never failed to include a fishing jaunt to Johnson Lake. The taste of those fresh-fried crappies is a tantalizing remembrance."-Harley O. Smith, Norfolk.

TAKE YOUR SEAT-"My husband's Aunt Ella Lull McBeth of Provo, Utah, tells some fabulous stories about earlier days in Nebraska when she was a girl. One of these stories involves my Uncle Fred Jurgensen of Cordova, Nebraska, who in the horse-and-buggy days, invited Ella to a basket supper at a country school near Cordova. Aunt Ella had been on her feet all day working in Otto Hassellback's store, and besides, she hadn't prepared a basket supper. But Otto encouraged her to pack a make-shift supper and Uncle Fred promised her a chair to sit on when they got to the school. So while Aunt Ella filled the supper basket, Uncle Fred rented a team at the livery stable, and in short order they were off to the social. They arrived late, and the school was crowded.

"Alright, Fred, where's that chair you promised me?' chided Aunt Ella.

"Uncle Fred thought a minute, looked out the window by which they were standing, then in a loud voice called out, 'Runaway team!'

"Every man in the building flew out the door except Uncle Fred, who pointed to the empty chairs and said to Aunt Ella, There you are; take your choice!'" — Mrs. Lloyd McBeth, Santa Clara, California.

THE CHINOOK by Mrs. Jean Brenneman Billings, Montana In the middle of winter, two pranksters one day decided a joke on Mother Nature to play; Old Sol and Miss South Wind —a daredevil pair—when they get together, let old Winter beware! While Sol, the old rascal, stayed hidden on high, the laughing Miss South Wind 'neath slate-colored sky Blew a blast of warm air on the whole countryside, and soon Mother Earth awakened and sighed; She pushed her brown shoulders right up through the snow —is it Springtime already, well, what do you know! So happy was she that she started to weep —'twas nice to awaken from such a cold sleep! As South Wind blew harder on Earth's frozen face the tears ran the faster — at a feverish pace; Racing and dancing around rock and tree, tumbling down hillsides, gurgling with glee, Millions of rivulets hastened below to join the huge puddles of fresh-melted snow. Biting and digging with all of their might, this pair made the snowdrifts fade out of sight. Some birds, too, were fooled—for a robin I see —and the buds are near bursting on the crab apple tree. But 'tis only a prank, as most of us know, for tomorrow 'twill likely be 30 below. NEBRASKAland APRIL 1970 5

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA . . . MONARCH BUTTERFLY

Subsisting entirely on milkweed leaves, this colorful insect tastes bitter but looks beautiful. Its weight increases 2,700 times in 15 days

ONE OF THE FEW insects that migrates, the monarch butterfly is the best known member of the order Lepidoptera. Although not as abundant in Nebraska as in some other portions of the United States, the Donaus plexippus is common here from May through October.

A member of the family Danaidae, the monarch is dull brownish-yellow and its main wing veins are outlined in black. It boasts a wingspread of 3 1/2 to 4 inches, and the outer margins of the wings are black with numerous white spots. Its colors fade in sunlight and will vary considerably with age.

Life begins in an egg, laid on the underside of a milkweed leaf. About the size of a pinhead, the egg appears gemlike when examined with a magnifying glass. Laid one to a leaf, the eggs will produce larvae measuring about 1.9 millimeters long and weighing about .54 milligrams.

After hatching, the larva will eat all or most of the egg case, after which it will subsist exclusively on the leaves of milkweed plants.

The period from hatching to moulting of the larval skin, as well as the time between moultings, is called instar. The monarch will go through five instars, during which it consumes large quantities of milkweed leaves and increases its weight to 1.5 grams. Occurring in only 15 days, the increase is 2,700 times its original .54 milligram weight.

Easily recognizable, the larva or caterpillar of the monarch butterfly APRIL 1970 is smooth and hairless with bands of black, yellow, and grey.

Mortality is greatest during the larval stage. For unknown reasons, the caterpillar will leave the milkweed plant where it hatched to search for a new one. This is done at random and, if another plant is not close by, the caterpillar will die from lack of food.

No birds will eat monarch larvae, apparently because of the bitter taste acquired from feeding on the milkweed plants.

If disturbed by prodding, the caterpillar will curl up and drop to the ground, where it will play "possum" for some time. And, only when on the ground is the larva in danger from predators, then it is readily eaten by mammals and other insects.

When the instars are completed, the caterpillar enters the pupa stage or the transformation from caterpillar to butterfly. This change usually takes 14 days, but it will occur much more rapidly in warmer weather and will be slowed by cool nights. Just prior to this period, the larva will generally leave the milkweed plant to form a chrysalis on the underside of some object. The chrysalis looks like a case of finespun jade and gold, but it is not a cocoon as produced by some of the moths.

The butterfly usually emerges from the chrysalis during the middle of the day, with small limp wings, which are stretched by a fluid forced into them. It takes from 2 to 17 hours before the monarch can fly. During this time, it must hang upside down from the pupal skin so its wings can form correctly. If it drops to the ground before it can fly, the wings will be deformed. The monarch will be sexually mature seven days after it leaves the chrysalis.

In late summer and early fall, monarchs begin their southward migration, which is almost undetectable because of its leisurely pace. They appear to feed at random, but closer observation reveals the southerly direction of their flight.Once believed to hibernate, monarchs have since proved to be true migrants. At this time, they gather in roost trees, since they must spend the night above the ground to escape predators. And, in some parts of the country, the same roost trees are used year after year.

Cold weather will halt the fall migration and any monarchs left in the North will die. Butterflies find it extremely difficult to fly when the temperature dips to 50 degrees Fahrenheit. At 40 degrees, they cannot fly at all. However, they can withstand subfreezing weather at night, if it warms up during the day.

Concentrations of monarchs make a spectacular sight on their wintering grounds along the Gulf Coast through southern Texas and Mexico and along the southern California coast. Some cities in southern California have even developed tourist attractions from the monarchs wintering near their towns. Some have passed ordinances protecting the butterflies from human intruders.

Come March and April, the more direct and rapid spring migration begins. Females move along, searching for suitable milkweed plants on which to lay their eggs. They will pick plants from 3 to 18 inches high, choosing young leaves so the first meal of the larva will be on a young, succulent leaf rather than one more rigid and mature.

Each female is capable of laying over 400 eggs, and since it takes about 33 days for a mature butterfly to develop from an egg, several generations can be produced each year. Once she has laid her eggs, the female usually dies.

The monarch ranges throughout the United States, but its distribution is governed by the availability of the milkweed plant. However, there are many species of milkweed, and the monarch is known to use 14 of them.

An unusual member of the wildlife kingdom in Nebraska, the monarch butterfly adds a bit of dash and color to the prairies. THE END

FOR FASTER ACTION

Impairing success and spoiling fishing pleasures, a dirty spinning reel is angler's killjoy companion

IN APPRAISING your tackle for the season ahead, now that winter has melted away, don't neglect the important job of attending to your reels. As every fisherman knows, the object of the sport is battling fish, not gear. A sluggish unresponsive reel not only impairs the chances of success, it spoils the lungdeep satisfaction of fishing itself.

While servicing spinning reels may seem more formidable than the less mysterious spin-casts, they present no problems if an orderly stripdown is followed.

First, cover a table or workbench with paper or an old pillowcase 10

As parts are removed, they can be cleaned by dipping them into a jar lid filled with cleaning fluid. For scrubbing gear teeth, a toothbrush proves invaluable.

Begin disassembly of the reel by removing the cover plate from the gearbox. Detach the gears and parts on the cover plate, clean them, and place the parts into the egg carton. As you reassemble, lightly grease the faces and teeth of the gears. Tubes of special gear lubricant are available at most sport shops.

Having reassembled the cover plate assembly, set it aside and follow the same procedure on the gearbox itself. When all the gears, the slide, and the slide guide are removed, clean the inside of the gearbox. Do not reassemble, however, until the bail assembly is serviced.

The bail assembly, located in the rotating head of the reel, is exposed by first removing the spool and spindle from the reel axle, then the baffle plate. Unless unusually dirty, the bail assembly need not be dismantled — a bath in cleaning fluid is sufficient. Grease should not be applied here. Instead, use a toothpick to oil all friction points.

Reassembly can now begin. Start with the gearbox, greasing the slide and gears as they are returned. Next, assemble the rotating head. Finally, screw the cover plate back onto the gearbox.

When the reel is together, check for smooth operation. If binding occurs, remove the cover plate and check the pivot gear, which rests against the slide inside the gearbox. These parts must mesh properly for smooth operation.

The final step is oiling all exterior moving parts. Remove the wing nut from the front of the spool, lubricate the brake spring, and the job is finished. Wrap the reel in plastic to seal out dirt and return it to tackle box.

To insure top reel performance, strip it down in the fall. After cleaning out the summer's accumulation of grime, grease the reel heavily to protect it from rust during its winter hibernation. Do this and your spring task will be easier. Besides that, you will be ready for action sooner, and in the long run your reel will last longer, thus saving you money. THE END

APRIL 1970FREE 70 EDITION

Wondering?

Phone ahead first LINCOLN TEL. AND TEL. COLIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS

AVAILABLE NOW!

McBride Fish Hatchery

• Fingerling Northern Pike • Bluegill • Channel Catfish • Walleye • Bass • Crappie • Trout Orders for Northern Pike and Walleye must be received before the end of May contact: Don McBride Orchard, Nebraska 68764—Phone 893-3785UNION LOAN & SAVINGS ASSOCIATION

NEBRASKAland's MONEYIand 209 SO. 13 • 56TH&O • LINCOLN 1716 SECOND AVE. • SCOTTSBLUFF

THE RUNAWAY MARE

ALL I COULD DO was run along behind the careening rig and hope that no one would be hurt before I could reach it. My son was inside and my sister, with her son. I knew they were in serious danger. I could think no further ahead than catching the horse and stopping the mad rush. But how could I outrun a horse? Maybe when she turned I could cut her off on her return trip.

The episode began late on a warm fall afternoon in 1966. It was the last ride of the day. As I loaded my sister, Diane, her son, Myron, and my boy, Brian, into the top buggy I had no suspicion that it would be a disastrous trip.

I climbed in behind the old cow pony and nipped the reins. Dusty was 19 at the time, and I was trying to prove that you can indeed teach an old horse new tricks. I had been training her as a buggy horse, and she had taken to her new assignment with all the philosophic calm of her years and gentle temperament.

The palomino mare had spent 10 years with our family at our vacation ranch near Comstock. Before then she was a member of a family with seven children, and all seven had learned to ride on her broad back. She was gentle. The children could walk under her without ruffling her calm.

Dusty had been a kind of neighborhood horse. Not only did the family use her as a live-in babysitter, but children on neighboring ranches also made liberal use of her services.

She had plenty of experience with youngsters, as the mother of three colts herself. She even had another after the accident — when she was 21 years old. Among her talents is her ability as a working cow pony. But on that day in November, she was the villain in a one-act, near-tragedy, not a responsible member of a ranching team.

We had started down a gentle incline just beyond the house and into an open meadow. As we started down, the shifting weight of the buggy broke a harness strap. The broken strap allowed the shaft to prod Dusty's rump. As I could see that she was getting annoyed at the indignity, I clambered down to calm her. But just as I reached for her head, she took off running across the field.

She had gone as wild as a spring colt. I couldn't catch her unless by some chance she might double back toward me before she dumped her load. Then it happened. I saw her 12

I sprinted to the shattered buggy where Diane was just getting up, dazed, and reaching for her son, Myron, who lay still. He was unconscious. I scooped him up and rushed to the house while my sister and my son, Brian, followed at my heels.

Myron regained consciousness at the house, but he just wanted to sleep. Still concerned, we decided to take him to the doctor who immediately placed him in the hospital for overnight observation.

Brian, in the meantime, had been complaining of a sore wrist. With Myron resting comfortably, the doctor had time to examine the wrist. It was cracked. Diane had a bruised forehead, but was otherwise unscathed.

When we returned to the ranch, we found that Dusty had wandered in, contrite over her misdeed, and dad had groomed her and corralled her. The buggy came in later, a piece at a time, although the broken shafts were the worst injuries to it.

The buggy top is probably the only thing that saved Diane and the children from more serious injury. Without the top, the buggy may have come to rest on them instead of the structure of the "roof".

Since the accident, the buggy has been repaired, and a team of ponies has been trained to pull it. Dusty is still going strong at 24, although she spends most of her time in the pasture now.

No one bears any serious scars as a result of the run-in with danger, but Myron still refuses to ride in the top buggy. It was a painful lesson, but it is well learned. I'm convinced now that, old wives' tale or not, you can't teach an old horse new tricks. THE END

Do you know of an exciting true outdoor tale that happened in Nebraska? Just jot down the incident and send it to: Editor, NEBRASKAland Magazine, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska 68509.This Summer, discover some of America's natural wonders

APRIL IS FOR MASTER ANGLERS

In the spring a fisherman's fancy turns to thoughts of lunkers. For these three avid buffs it meant "double-up" wins on hook and line

April is a month when most outdoorsmen are thinking about fishing and just haven't done anything about it. But, there are some hardy souls who have found that this spring month is packed with fishing action. From the looks of a list of April 1969 Master Anglers on page 58 and 59, it seems this is the month when lunkers shake the laziness of winter and go on a feeding spree. For three fishermen, April is a time to remember and here are their stories:

TO SOME, April showers bring May flowers. But to Terry Richardson of North Platte, April means the perch move into the inlet of Lake Maloney. Anyway that is why the railroad man decided to spend April 14 at the lake just south of his home. It was his first outing of 1969, and as an ardent angler, it was the start of his long fishing season.

After pulling his car to a stop on the north side of the inlet, he quickly ran the 8-pound-test monofilament through the eyes of his 6 1/2-foot rod. Opening his tackle box, he took out 2 tiny mites and tied them 1 1/2 feet apart on the line. The previous April, the perch had eagerly taken either minnows or the small-jig-like lure.

At noon he made his first cast, and by 2 p.m. he hadn't had a strike. He knew the fish were there because his friends had been landing them. Discouraged and puzzled, he scanned the inlet's water.

"There's a good minnow trap and big fish are probably nearby," he thought as he eyed a swirl of water.

Terry made a cast toward the spot and started a slow, jerking retrieve. When his double-lure combination was just four feet from shore a dark shadow unsuccessfully tried to steal the trailing tiny mite. The North Platter was fishing for perch, but if a bigger fish wanted to taste steel, he would be ready.

After loosening the drag on his reel, Terry threw to the spot again. This time (Continued on page 58)

AFTER THROWING ACROSS the rapids, Denny Doolittle worked the lure back through a deep pool at the end of a long, white-rippled chute of water. As he did, a big brown trout flashed out of the depths, smacked the two-way spinner, and nearly tore the 7 1/2-foot fly rod out of the angler's hand.

The Valentine fisherman had played his share of trout, but he had never felt the throbbing thrust of a fish like this. His heavyweight opponent was big because he was smart and aggressive, so it was evident that he wouldn't be an easy quitter.

After diving for the bottom of the pool, the trout rocketed upstream into dangerous, snag-infested white water. Unable to shake the snare on his upstream rush, the fish sulked, then turned downstream. That is all the edge Denny needed to pressure the brown back into the pool where he was easier to handle. After a 15-minute struggle, a deft swoop with the net ended the fight.

"Time to head home," Denny thought as he hefted his first Master Angler fish, a 4-pound, 2-ounce brown trout. "There's still plenty of fishing time left, though. Maybe I will try a couple more spots."

Denny was reluctant to head back to town because Sundays are the only time he can pursue his favorite hobby, trout fishing. The April day was warm, the sun was shining, and the Snake River canyon had the fresh smell (Continued on page 59)

DARKNESS WAS AN hour off when Ted Voet pieced together his 6 1/2-foot, medium-action rod. The April evening was chilly, but the thought of bass warmed Ted as it had all winter. For the last 21 years he and his wife, Lorraine, had made it a point to fish Niobrara State Park lagoon or other Knox County waters in either late April or early May.

To the Omahan there is only one kind offish, the largemouth bass. In two decades of fishing the Knox County area he has caught hundreds of them, with the biggest tipping the scale at 4 1/2 pounds. Ted keeps pictures instead of bass, so after photographing them he returns the fish to the lake. On this trip, he hoped to add a few more memories to his photograph album.

Fishing for black bass takes persistence and patience. The sales-manager for an Omaha van and storage company had already resigned himself to the fact that this hour of fishing was, at the very most, a scouting expedition for the next day's effort. Through the years Ted has found that bass and purple worms are go-togethers, and he anxiously tied one to his eight-pound-test monofilament.

On this trip his wife had offered him a challenge. If he could land a bucketmouth over five pounds, she would have it mounted for him. As he surveyed the lagoon, he had that challenge in (Continued on page 64)

SIX MINUTES TO TOMS

An electrifying gobble shattered the morning stillness. Turkeys and hunters were ready to go, but watches and the law told us to wait

WITH A PAIR of wild gobblers 10 feet in front of me, a loaded 12-gauge shotgun 12 feet behind, and 6 minutes to go until legal shooting time I was in a predicament.

"Oh, brother, don't let Cecil get trigger-happy or I'm a goner for sure," I prayed, pressing deeper into the duff below the low-branched cedars.

The two toms on the crest of the little slope sounded off with a string of suspicious gobbles. They sensed our presence even if they couldn't see us. I didn't dare raise my head, but by rolling my eyes upward I could see the birds silhouetted against the brightening sky. They were facing each other, and as I watched, the two crossed heads, their wattled necks forming a living "X" against the light. I knew Cecil McCullough could see them, too, but could he see me? It was still very dark under the trees and to make matters worse I was dressed in dusky green which blended perfectly with the shad- ows. A faint rustle behind me set my imagination off.

"He's raising his gun. He's goint to shoot," my panic shouted. "Jump up, run, yell, do something-do anything!"

I stifled the impulses and hugged the ground flinching against the anticipated blast. My partner's angle was such that if he shot, the charge would pass over me. At best, the 1 1/2 ounces of No. 6's would be some 2 feet above me. At worst, they would smash into the back of my head and spoil my turkey hunting.

Although Cecil and I had planned our 1969 spring hunt for weeks, all the preliminaries were conducted by phone and letter, and we hadn't met until the Friday afternoon before the opener. A few minutes' conversation convinced me that he was a solid and experienced hunter, but in a situation like ours the best of men can get "shook". Besides there was a good possibility that Cecil couldn't see me. Still, I had to have faith or blow whatever chance we might have to nail the two gobblers.

The whole thing started when I bought a spring-gobbler permit for the Niobrara unit and cast about for a hunting partner who knew the country. Mutual friends told me about Cecil McCullough, a farmer-rancher whose spread is along the banks of Pine Creek in north-central Nebraska.

"Cecil is a mighty good turkey hunter. He gets his gobbler every spring, he's a first-class caller, and a darn fine shot. McCullough is your man," my contacts told me.

A few phone calls and a couple of letters firmed up the details and on an April afternoon before the season opener, I drove north out of Bassett to Cecil's place and introduced myself. The lanky westerner suggested a quick scouting expedition that evening to get a line on some roosting toms. It seemed like a fine idea, so we worked up Pine Creek to its junction with Bone Creek and followed that stream into the canyon country. My companion made a few tentative calls on his homemade box caller and it wasn't long before we got an inquiring gobble back. That first answer triggered several others and Cecil estimated four toms were in the canyon.

"They're roosting in the evergreens and oaks across the creek," he decided. "In the morning we'll come in from the other side and try calling them. We ought to be situated at least 30 minutes before shooting time. That means we ought to get started about 4:15 a.m. It will take us about an hour to walk in."

We were a little tardy getting started and it was inching along toward opening hour as we single-filed our way through a branch canyon that led to the creek. Turkey hunting is a stealthy business, so we loaded our guns early, for even the racking of a shell into a chamber could spook the wary birds. Cecil was using a 12-gauge slide-action while my pet, a 20-gauge side-by-side, was loaded with No. 5's.

We were about 250 yards from our preselected spots

and the going was pretty steep, so to favor a tricky

back I picked a little easier trail than the one Cecil

was following. I was slightly behind him and about 12

feet to his right when an electrifying gobble, gobble,

gobble shattered the morning stillness. The sounds

were very close and we knew that we had to get out

of sight but quick. Cecil sort of flowed into the trunk

of a big tree, but I was more in the open and had to

dive for a stunted cedar directly between my com-

panion and the two toms. The turkeys were alert, but

they were more curious than spooked and in no hurry.

They gobbled and strutted around and once they came

so close, I was sure they could hear the pounding of

my heart. Finally the birds worked out of sight, foraging along a little bench that shelved out from the

canyon. When the expected shot didn't come, my apprehensions dissolved into bitterness.

canyon. When the expected shot didn't come, my apprehensions dissolved into bitterness.

"Of all the miserable luck," I thought to myself, "two toms in spitting distance and I couldn't do a thing. I'll never get another chance like that again."

I stayed put, for the turkeys were still in the immediate area and there was a thin chance we could call them back. I risked a look at my watch, it was now legal shooting time. Suddenly, a shot completely short-circuited what few nerves I had left. They say a man can't jump from a prone position. Nonsense. I came three feet straight up.

Cecil's soft "got him" didn't register at first, for I was fighting a bad case of the "shakes". Finally, the rubber went out of my legs and with nonchalance I strolled to where my companion was admiring his gobbler. The bird was a fine one with a 4-inch beard and weighed 18 pounds, 8 ounces after field dressing. The successful hunter filled me in on the details.

"I had a hunch the birds might circle. Turkeys often do that when they are suspicious but not really spooked. Sometimes the birds will follow a little drainage or some other terrain feature to get in behind you. This one circled around that way," he said, pointing to a shallow erosion ditch.

'You had me sweating that you were going to jump the season. By the way, did you see me sprawled under that cedar?" I asked.

Cecil grinned. 'Yep. I was sweating you out, too, especially when the birds had their heads crossed. I never saw anything like that before in my life. It was a sure two-for-one opportunity if it had been legal to shoot. How would you have handled it?"

"I don't know," I answered truthfully. "They were an awful temptation but honestly I don't think I would

Cecil was sure the surviving torn had fled east, so he suggested we climb back to the tableland, walk about half a mile, and set up at the head of another canyon to possibly intercept the gobbler. He wasn't optimistic, for several hunters were in the same area, and we could hear a discord of calls as they tried to entice some toms. Both of us knew that as time wore on, the gobblers would become more sophisticated and wary of phony "girl friends". We tried but it wasn't to be. Once we got a gobble back but the bird kept drifting away and we gave up on him. We spent the day trying to luck into some birds, but fortune wasn't smiling at us.

That first day was ideal for spring turkey hunting. It was bright and calm with just enough tang in the air to add spice to the outdoors, but the next morning was a different story. It was very windy and Cecil told me that toms usually clam up on gusty days and refuse to answer a call. We kept at it from opening minute to closing hour but all we got was exercise. That evening my host came up with an idea.

"A friend of mine ranches over north of the Niobrara River and from time to time turkeys come in to graze on his alfalfa field, usually in the evening. Let's hunt the canyons in the morning and if we don't do any good, go over there after lunch."

Our morning hunt was fruitless, so we headed for the other area and another first in my outdoor career. There was a little edging of brush in front of some cottonwoods that fringed the field, so I roughed out a makeshift blind and settled in for a long wait. Cecil hid in a little grove catty-cornered from my spot after we arranged to signal each other if we saw any birds.

It was warm and I was tired. Pretty soon, I dozed off. A fox squirrel in a cottonwood behind me sounded off with a chattering scold. His noise shook me out of my languor and I peered out of the blind. Four white-tailed does were right in front of me. One had a mad on against the world. She didn't like squirrel racket at all. The bushytail would reel off a long snicker of insults and she would counter with snorts and stomps. For 15 minutes, the two animals chewed each other out — chatter —stomp —snort —chatter. Finally, the squirrel must have given out with a real stinger, for the doe lowered her head and came forward at a purposeful trot. Twenty feet, fifteen feet, ten feet, and then she was practically eyeball to eyeball with me. I froze and waited.

A whitetail is an admirable creature —at a distance. At 10 feet, a whitetail, red-eyed and raging, is the perfect epitome of wild fury and a lot more frightening than appealing. Her hooves looked mighty sharp and I knew that if she piled into me I would have contusions and abrasions to spare. Still, I was curious and wanted to see what the deer would do. The other three closed in behind their antagonistic companion and there was a distinct possibility that very shortly I was going to have a lapful of deer.

The angered doe was really on the prod now. Every hair on her neck was bristled up, her nostrils were flared to twice their normal size, and her eyes, normally limpid, were practically red (Continued on page 51)

WONDER THE WORLD

Nebraska's State Capitol is magnificent example of man's mortar and mosaic handiwork

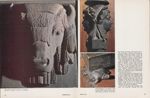

BANKS OF orange-tinted clouds lining the western horizon reflect the final burst of beauty of the dying day. Such a scene only the Old Master Painter could create, but what a breath-taking backdrop for one of man's greatest masterpieces... the "Tower of the Plains".

It is a fleeting moment to be treasured and finally stored in the album of memory, for once gone it will never be quite the same again. And so, the sun sets, but its passing tickles the imagination and excites a curiosity about this "architectural wonder of the world".

If the mere sight of such a building can so inspire a viewer, what then lies behind those massive doors?

Symbolism fills this majestic edifice — from the Sower perched atop the 400-foot tower to the intricate designs of the interior corridors and chambers. It is more than just a home for government, for it mingles the ideals and accomplishments of a great state and its people.

Everyone views such a structure in the light of his own experiences and interests. An engineer admires the graceful lines of a well-constructed building. An artist sees the lights and darks and tiny details

The casual observer is often awed by the massive splendor of the huge structure, with its marble columns and towering ceilings. It is too much to absorb in just one visit, for one can grasp only the obvious. But, each succeeding trip will reveal "hidden" delights tucked away among the balconies and balustrades. Even such mundane objects as doorknobs shine as works of art.

Ground was broken for what was to become a masterpiece of the builders' skill in April, 1922, and this unusual State Capitol features the very best that its master architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue could obtain. Ten years in the building, it cost about $10 million but, today, would cost 7 to 10 times that amount. And, no detail was so unimportant that it could be overlooked.

Each minute item has its place and,

thus, was carefully blended into the

APRIL 1970

25

Meanwhile, soft light filters through onyx windows framed with Colorado yule, and a close look reveals that same ultra-white marble in the balustrades of the balconies around the rotunda. There, too, careful scrutiny reveals such works of art as onyx meadowlarks.

Surrounded by well-manicured lawns, this unusual statehouse centers four square blocks in the heart of Lincoln. The tower rises from the very core of this "cross within a square". Individual little courtyards nestle within each interior corner.

Heroic figures of charity, faith, courage, temperance, wisdom, justice, and magnanimity dominate the rotunda dome in the heart of the Capitol. Twenty-four pillars of French marble, noted for its regular veining and soft glow, appear to support the dome but do not. The intriguing mosaics throughout the building required

years of painstaking effort to cut, fit,

and place.

years of painstaking effort to cut, fit,

and place.

A mammoth array of murals, carvings, and mosaics tells in graphic detail the inspiring story of the world in general and the Great Plains in particular. Loving hands recreated in stone, tile, wood, and canvas the fascinating sagas of the ages. From the magnificent chandelier in the great hall to the infinite detail in the working chambers, artists and craftsmen blended their talents and skills to create a structure of which all Nebraskans can be justly proud.

From the elaborately carved walnut ceiling in the Supreme Court chamber to the 1,500-pound Indian doors of the old Senate chamber, the beauties of this fabulous edifice wait to be discovered. Guided tours, conducted every day, are the ideal way to become acquainted with this great building. But, to really see its magnificence, amble through its halls and galleries at your own pace. Scrutinize it and savor its beauty. After all, it belongs to you. THE END

Next month, NEBRASKAland will present the second and concluding series of color photographs on the oft-overlooked little things that help make Nebraska's State Capitol an architectural wonder of the world.

THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM

Heated grandstands at Fonner Park add living-room comfort to the "Sport of Kings"—horse racing

FIRST CLASS thoroughbred racing in March? In Nebraska? Impossible, snorted oldtimers only a few years ago. But they're believers today, as they watch the first race of Nebraska's season each year from the comfort of a glass-enclosed grandstand at Grand Island's Fonner Park.

At one time, this "Sport of Kings" was thought to belong only to a few balmy, sun-sprinkled spring and summer days. But tracks like Fonner Park have proven this idea wrong and have given thoroughbred fans many extra days of sport in the bargain.

Action at this initial meet of the Nebraska season may take place in a chilling wind and cold rain, or a few snow flakes may sting the jockeys and their mounts. But, the weather will not dampen the spirit or chill the enthusiasm of the fans, as they remain snugly perched at good vantage points in the heated grandstand.

Racing buffs look over the ponies in an enclosed paddock, make their selections, then place their bets in the concourse or mezzanine, and cheer on a longshot or a favorite from the heated stands, all without exposure to the elements. Only the ponies and their riders must face the weather, and then only for the few short minutes and seconds during the heat of competition.

Every aspect of the park is geared toward the early opening date and all-weather operation. The sensitive hooves of thoroughbreds run on a track that is treated with 75 tons of salty anti-freeze and kept clear of snow throughout the long winter.

Even training has been "winterized" at Fonner, the most complete all-weather track in the state. Now trainers can work their horses all year long if they wish, because a new 112,000 square-foot multi-purpose building finished in February includes a quarter-mile track under its roof. Now (Continued on page 53)

30

THE STEEN YEARS

A dedicated public servant with ability to dream and make his dreams come true — that's Game and Parks Commission's "Tiger on the hill"

MELVIN O. STEEN is a much "cussed" and discussed man. The short, chunky, white-haired chief of the Game and Parks Commission exudes vitality and energy. He demands the best from those associated with him and he usually gets it or "a pretty good reason why".

In the 14 years since he came to Nebraska, he has made friends and he has made enemies, for no man who takes a firm stand on issues can avoid incurring someone's displeasure. Few people will take a middle ground when his name enters a conversation, for Mel Steen is a mover and a shaker. And, he has moved and shaken the lethargy from a good many Nebraskans.

But, what is more important, he has accomplished the lion's share of the tasks he set for himself when he came here in 1956. Unquestionably, he has stepped on some toes in the process, but tender toes, be they friend or foe, had best move out of the way when M. O. Steen goes in motion.

The "tiger on the hill" seems to thrive on controversy—at least, he never let it detour him from a course he felt was right. And, sometimes the controversy could become pretty heated, but like a Missourian named Harry Truman said, "If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen." Mel Steen has stayed in the kitchen.

One of the most flamboyant characters to grace the Nebraska scene in many a year, Steen is the first to admit that he could not achieve his goals alone. He had not only the backing of his Commission, but the aid of governors, state senators, other agency heads, and the ear of many influential people in Washington.

M. O. Steen is a determined man, a man who has never learned to take "no" for an answer. Who he knows and what he knows are essential, but his bulldog tenacity brought him success where less determined men would falter and fail.

"Whether a project is popular or unpopular is beside the point," he admonishes. "That is no criteria. And, there is nothing that cannot be changed if it is the right thing to do. It might take 25 years, but I'm not going to quit just because of rules, procedures, or red tape."

Perhaps that statement is the key to the personality of this complex and knowledgeable man who has accomplished so much in less than a decade and a half.

A dedicated public servant with the ability to dream and make those dreams come true — that is M. O. Steen.

Asked to list what he personally considers his greatest achievements during the past 14 years, he leaned forward in his chair and pondered for many moments. And, that is not surprising, for this man has many accomplishments to ponder. He then reached for a pen and paper and began to compile "his" list. As the conversation continued that afternoon, he would pause from time to time to make another entry.

That list goes something like this, although not necessarily in order of importance: Chain of Lakes, Scouts Rest Ranch, restoration of Fort Kearny, development and expansion of Fort Robinson State Park, acquisition and development of Ash Hollow State Historical Park, developments on the Salt Creek reservoirs, development of the Rock Creek Pony Express Station, development of Lake McConaughy and the southwest reservoirs, initiation of Indian Cave State Park, development of Two Rivers with its fee trout fishing, acquisition and proposed development of APRIL 1970

As he spoke his eyes twinkled and he relished the recollections of battles fought and won and others waged and lost. It is easy to see that of all his endeavors, his pets are the Platte Valley Chain of Lakes and the restoration of Buffalo Bill Cody's Scouts Rest Ranch.

He recalls his first visit to Nebraska after accepting the job as director. A cattle raiser in Missouri and interested in polled herefords, Steen made a special trip to North Platte to see Orville Kuhlman's prize bull "Goldmine". That trip to see Kuhlman, who ranched Buffalo Bill's old spread, proved to be the beginning chapter in the ultimate restoration of Scouts Rest Ranch —now Buffalo Bill Ranch State Historical Park.

When he returned home full of enthusiasm about Goldmine, his son Lloyd kept prodding him about the famous ranch. The younger Steen could not believe that such a historical place was simply another cattle ranch. It set the new Game and Parks director to wondering, too, and in his new capacity he could —and would —do something about it. Ultimately, with the dedicated aid of then Commissioner Don Robertson, the City of North Platte and the State of Nebraska purchased the land where Buffalo Bill's home and barn stood. Progress was slow, but now visitors from across the state and nation enjoy the fruits of those labors.

Many areas attracted Steen's attention and stirred his interest. What he saw was a tremendous challenge to move Nebraska forward in all areas of the Commission's responsibility, be it parks, fisheries, game, or land management. Not many years passed before the Legislature turned the promotion of travel over to his capable leadership.

"Nebraska had and has great potential as a travel market," Steen stressed. "But, there were many problems. Tourists avoided Nebraska. They felt there were no roads, no accommodations. It was then the idea for the developments along Interstate 80 began to crystalize. I realized that the great Platte Valley always had been and would continue to be the natural pathway for East-West travel. It is the major artery between the populous East and the playgrounds of the West.

"But...we had an image to change. Out-of-staters felt that Nebraska was a nowhere place in the middle of the country with nothing but farms and cows. No one had told them about this state's magnificent western heritage... about Fort Kearny or Scouts Rest.

"Thus, preservation of our heritage serves a dual purpose —honoring the past and filling a need in the tourist-promotion field. So, too, the Chain of Lakes serves a double purpose —to beautify the Interstate and to stop travelers who might just keep on going."

Nebraskans now point with pride to those scenic little oases along 1-80, known as the Chain of Lakes, but once they laughed at the idea and the man who proposed it. While much remains to be done in the Chain of Lakes development, the groundwork has been laid and the project is well on its way.

Many a Nebraskan has changed his views after one of Steen's fact-filled discourses, and the curved index finger has become a trademark as he drives home a point.

Under his guidance, Nebraska pioneered in the field of pheasant management, innovating a program NEBRASKAland

Thus, the Commission undertook two major steps: (1) attempted to hold the line on the environment through the maintenance of permanent cover and tried to maintain cover on a large scale through federal projects such as the soil-bank and Cropland Adjustment Program (CAP) and (2) provided trees and shrubs to farmers for conservation practices.

Steen was a motivating force behind both the soil bank and CAP, since he was the first wildlife man in the country to espouse the soil bank. CAP came about as a result of another proposal he made to the American Association of Fish and Game Commissioners when he was chairman of a committee on land use.

"Trouble is," Steen fretted, "that these programs are much too limited in scope. Our ability to put cover on the land falls far short of any substantial accomplishplishment. At the present time, CAP has enrolled 198,000 acres in Nebraska which cost the federal government $4 million a year. To restore the cover as it was in the late '30's, we would have to retire between 5 million and 8 million acres, for that was the amount of land that lay idle at the peak of the pheasant's heyday.

"I get the feeling of a little barefoot boy with a wooden sword trying to stop a 40-ton tank, when I think how the cover is disappearing. We are losing it eight times faster than we could ever put it back. We must work through the farmers and make it economically feasible for them to preserve cover. That is why stocking is not practical. If we ever get as hard up for birds as New York or New Jersey and hunters are willing to pay $5 each for pheasants, then stocking would be feasible. While (Continued on page 51)

APRIL 1970

MEMORIES OF A SCHOOLMARM

Three R's become five as I add rattlesnakes and revolvers to our education on the plains

MY FIRST DAY in that early Nebraska school was just about my last. It began with eight pupils in eight different grades, all studying from different texts. It ended with a rattlesnake. I had to dismiss my class through a window because the snake blocked the door.

I'd been told that it wouldn't be easy, but I wasn't prepared for this all at once. I learned fast, though, out of necessity. Before the year was over, that mother rattlesnake gave birth to about 20 snakes in the shelter of my schoolhouse. Almost all prairie wildlife made its way into the building at one time or another.

Not all unwanted guests were varments, though, and I took the advice of the previous schoolmarm. I kept a revolver handy to protect against cowboys as well as snakes.

I soon found that I had to be ready for anything, from snakes and coyotes to parents anxious about their children's morals and manners. The upkeep of the schoolhouse was my concern. And that meant getting there early in the morning to start the fire. At night, I turned janitor and cleaned the soddie.

My pay matched the times. A salary of $36 a month in those days, 1885, was high. That doesn't seem like a lot until you realize I only paid $1.50 a month for room and board —before I homesteaded my own land. I was paid only for the days I taught. If a snowstorm canceled school or if too many pupils were in the fields, my PaY was docked for those days.

My dress, hours, and habits were strictly regulated for the protection of my students. I was to set a perfect, or nearly perfect, example. Some contracts in those days even regulated courting, including the number of evenings that the teacher could go "out". She must be in by 9:30 or 10 p.m. A drink of alcohol or a puff of smoke was grounds for automatic dismissal. There were few married schoolmarms.

Helpful hints for the teacher later appeared in The Nebraska Teacher, first issued in September, 1898. We muddled through somehow before that. The magazine carried instances of teachers being dropped for dancing and card playing. It noted that married women were discriminated against as were Catholics.

Some school boards were said to be concerned because young lady teachers seemed overanxious for husbands, having company too much to do their homework.

An editorial warned of bad breath and body odor, suggesting that a teacher brush his or her teeth three times a day and spend 60 rather than 15 cents a week on laundry.

To the early settlers of Nebraska, education was the road to a better life for their children and they insisted that the youngsters be given a good example

while they learned reading and writing. Often even the

members of the early school boards couldn't read or

write. On one occasion in my district, the board offered

help in "lamming" the big students if necessary.

while they learned reading and writing. Often even the

members of the early school boards couldn't read or

write. On one occasion in my district, the board offered

help in "lamming" the big students if necessary.

Once the pioneer families were housed, a school was the next concern. At first there were no teachers and no schools as such. The center of education was a corner of the family soddy and mother was the teacher. But gradually, the women who had had the most education back East were singled out as instructors for the neighborhood children.

The first Hall County school opened in 1864. It was run by a farmer for the children of neighboring families. The other farmers paid by working his land.

Later, teachers were "imported" from the East. Our first school was formed when four families clubbed together and hired a teacher. One room was set aside in the homestead as a schoolroom. "Mother" also kept the schoolteacher and her two little girls. At that time the family had increased to nine children.

As time passed, Nebraska's pioneers decided that schools should be separated from the distractions of a home. New locations were sought, some of which would be considered impossible today. Part of a one-room grocery served as a schoolhouse, while the front part of a carpenter shop did its share, as did the attic of a home, a granary, and a vacant saloon. Finally separate schoolhouses appeared. They weren't fancy, but they served the purpose.

Severe snowstorms blew across the prairie in winter, and drought, prairie fires, and grasshoppers took the crops in summer. The Pawnee Indian Reservation was only a few miles away.

Prosperity meant schools; times of troubles meant none. In the old days blizzards raged across the plains with all the fury of the elements unleashed. In the open, treeless spaces, almost any snowstorm could become a blizzard when tossed before a blustery wind. School was then dismissed or cancelled in an attempt to protect the children. During the blizzard of '88 I dismissed school early, but before anyone had left one of the fathers came with a lumber wagon and said, "I'll take all going south; the rest stay here till someone comes for you." And to me he said, 'You stay till the

Another teacher tied all the students' horses together and took them home one by one during a later blizzard. He then stayed with the Kinkaiders at the end of the line.

A 16-year-old pupil of the first Hall County school was killed by Indians while hunting on the Loup. But despite danger and discomfort, students came, and school was held no matter what.

A Cherry County teacher recalls a little girl who rode horseback — with her skirts blowing. Even in below zero temperature the child would ride to school, bare knees raw with cold.

"I started to school in the third grade," ex-Nebraskan Tom Adams wrote me, "and walked 2 1/2 miles each day, as there were no buses in those days. During the fall harvest season, and spring plowing and planting, there were times when I was the only pupil in school, but we had our regular classes, regardless. The main subjects were the three "R"s, with geography and physiology besides. Nothing was furnished the pupils in the way of entertainment or athletics."

School started the first of September and ran for nine months, with only a week's vacation at Christmas time. Then the teacher got to go home for a visit. The rest of the time I stayed at one of the homes in the district and sometimes had to walk over a mile to my school. I had to get there early enough to build a fire in the stove, do the sweeping and dusting, and get a pail of fresh water before the pupils started to arrive."

And water was often a good distance from the school. Sometimes one of the older boys carried water from a nearby farm. We had one dipper and had to watch the boys and girls so they would not pour back the water left in the dipper. You know it was hard work to carry water by the pailful.

In the days before the population explosion, prairie homes were spread long distances. Children were forced to walk a far piece for their education. To prevent the youngsters from getting lost, dad would plow a furrow from home to the school each fall before school started. To lessen their children's walking distance, home- steaders sought to have the (Continued on page 52)

Photos courtesy of Nebraska State Education Association

AGELESS CITADEL

Resembling a Spanish fort, Beaver Wall withstands the onslaughts of time

40 NEBRASKAlandTOWERING OVER the tranquil valley like a gigantic fortress on the edge of Nebraska's Pine Ridge, stands rugged, pocked Beaver Wall. Closely resembling a Spanish fortification built to withstand the onslaughts of vengeance-seeking crusaders, Beaver Wall is actually a natural phenomenon. For centuries, however, its buttresses and ramparts have constantly been beseiged by even more formidable enemies than human armies-time and the elements.

Though appearing indestructible, the ponderous stone castle, complete with

turrets, spires, and cannon ports, is slowly ebbing in magnificence. Basic forces of

nature combine to chisel at the foundations. The abrasive winds cut gaping holes

APRIL 1970

41

Visible from the county road wending its way from Chadron to Whiteclay, Beaver Wall has looked down upon the puny efforts of man to tame the land. For centuries, the escarpments led only to the impenetrable base of the varicolored wall. For nearly three miles the bluff was an insurmountable barrier save for one chink in the armor. There, like a drawbridge, a narrow trail wound up the 300 feet from valley floor to bluff top. Along this trail rode Indian hunting parties, trappers and their fur-laden horses, an occasional cowboy, and later youngsters who utilized the 42 NEBRASKAland

The citadel has witnessed much history. Its moat is Beaver Creek, a mere

trickle meandering near the wall's base. Along the stream banks many forms of

wildlife browsed and dozed, so the Red Man found hunting productive. Later, when

conflict with white settlers became necessary, the hunting parties turned into war

parties. Chief Crazy Horse rode there and was reportedly buried in the shadow of

the cliff. Soldiers also traversed the area, and General Sheridan camped nearby.

Arches carved out of the soft stone by sand-laden winds are unique in this part

of the country, resembling the deep-canyon etchings of the southwest. A geological

APRIL 1970

43

As with all things, time is the greatest threat. Inescapably, the great wall is being sapped of its substance and stature. Gradually the sheer cliff is slumping and crumbling to form a gentle slope. Pine trees and prairie grasses climb ever 44 NEBRASKAland

Many centuries more of observing the countryside lie ahead for the great castle, and it will continue to endure the ravages of battle with the elements. Though its fate is sealed, it can fight valiantly against the inevitable as it has in the past. Perhaps the most strenuous destructive forces are gone now, and the aging fortress can more gracefully surrender its battlements to some future victor, yet the same one that created it in the first place. Until then, the stark beauty of the battle-scarred wall is a monument to its long, patient vigil. THE END

APRIL 1970 45

OLD YELLER ... OR SAM

He was a mongrel and a drifter, but he knew his way around. And, his independent spirit brought sadness and happiness to two families

FOR SEVERAL DAYS before he strolled into the yard, we had noticed him wandering around the farm like a penniless gentleman. When he finally decided to walk into our lives, we knew that the drifter would probably leave again some day. But even so, our family became very attached to him.

He was a long-haired dog with a white ruff, white head, and a white-tipped tail. The dog was part collie, but instead of a long, pointed head, his muzzle was short and blunt. In addition to his white markings, he was sun yellow. That is partly why we called him "Old Yeller".

When he proudly walked into the yard on that first day, I picked up a broom to chase the stray away. As I did, the shaggy dog nonchalantly walked into the shade of an elm tree and laid down. His right ear was bent down, he was covered with dirt, and I could see that he had been in a fight. Instantly I wanted to help him, but somehow I knew that he did not want or even expect any aid. Returning to the house, I exchanged the broom for a pan of cool water.

For several days Old Yeller remained in the shade of the elm, watching every movement around him and getting up only to eat. But one morning he slowly got to his feet and ambled after my dad and brother, Raymond. For a while he watched them drive in the cows, then he decided to lend them a hand. As a trail herder he was an immediate success and that day the cows came home in two herds. Dad and Raymond drove one, but Old Yeller had his own and he kept the nervous cows moving by nipping at their heels and pulling their tails.

The mongrel won our hearts without any trouble, but Mom was skeptical about the dog. Her theory was that he was just another stray that someone had dumped in the country while still a puppy. But the drifter had some habits that I knew he had to learn from a master. For example, he used to stand and wait for me to dump food scraps into a bowl before he would eat. It amused me to see him look down his nose at the other dogs and cats as they scrambled for the bowl the minute I walked out of the door.

An avid hunter, my father had spent one year training a young female called "Snoppy" to retrieve. When Yeller came, it was inevitable that he would go hunting, too. On his first excursion he watched the younger dog work and then evidently thinking he could do a little better, he joined in. It wasn't long before he convinced both Snoopy and dad that he was going to do the retrieving.

After Yeller had been with us a year, we felt sure he was ours forever. In fact, two incidents with Fritz, a big German shepherd, seemed to prove that the onetime drifter considered us as his family.

One morning, Fritz, who was trained as a police dog, then sold to a neighbor because he would not obey, wandered into the yard. Unlike Yeller, who had grown rounder, and stiffer (Continued on page 62)

CLEAR CREEK REFUGE

Benefiting both gunners and geese, the area provides sancuary for thousands of honkers every year

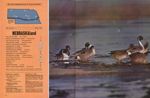

48 NEBRASKAlandMAJESTIC CANADA GEESE are hardy birds that can survive most of the hazards nature throws at them. But these long-distance flyers need stop-over areas on their yearly migration. That is why there is a need for places like Nebraska's Clear Creek Waterfowl Management Area.

Located on the west end of Lake McConaughy, Clear Creek was established in 1960 to give shell-shocked honkers a breather during their fall migration. Although the land belongs to the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District, it is leased to the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission for wildlife management. The surrounding terrain varies from marshes to farmland to high bluffs, and offers these marathon flyers a desirable combination of land, water, food, and sanctuary. The tract consists of 2,300 acres, although the Keith-Garden County refuge is upriver, and Lake McConaughy spreads out below the area.

Clear Creek gives geese a place to feed and rest, and their presence means more hunting for waterfowlers. The increased shooting opportunity has created some problems below the refuge, however, mainly through increased competition for hunting and blind sites. The Game and Parks Commission is in the process of taking a closer look at the Clear Creek area, with hopes of establishing a more workable hunting arrangement for future goose seasons.

Each fall, 6,000 to 13,000 geese visit the area, and hunters annually harvest from 600 to 900 birds as they fly from the refuge to feeding grounds or to Lake McConaughy. First viewed as an encroachment on their hunting opportunities, hunters now support Clear Creek because it increases the number of geese and lengthens their stay in central Nebraska.

Before the refuge was established, the number of Canadas in the area was diminishing from year to year because of excessive hunting pressure. One year after Clear Creek's establishment more than 1,400 geese wintered there and in 1966 an estimated 13,000 Canadas stopped in. About 7,500 of these geese remained until December 1 and about 3,500 stayed through the winter. Observers estimate the peak for wintering Canadas was in 1963 when 5,000 geese were counted after January 1.

A benefit to both gunners and geese, wildlife-management success at Clear Creek did not just happen when boundaries were drawn and land was declared off limits to hunters. Liberal use of axe and elbow grease eliminated undesirable willows, cottonwoods, and Russian olives along the North Platte River. A herd of goats was a less successful tool in combating bulrushes and willows on islands in the Platte. These constantly browsing critters were supposed to eat the undesirable cover on the islands. But the grass must have seemed greener on the far banks, for the animals paddled ashore.

Besides converting the land to the more open terrain preferred by spooky honkers, providing food during their stay is another major job. Tenants, sub-leasing lands during the nine months when honkers are absent, pay their rent with a share of their crops. Most of the Commission's share is left standing in the fields for the geese. Though most of the land is farmed by tenants, Game Commission personnel do some planting. Winter honker food includes grain crops and goose "pastures" of winter wheat, rye, and fescue.

Caring for a penned resident flock of more than 50 wing-clipped Canadas is another major task at Clear Creek. The purpose of the flock is to raise young Canadas for Clear Creek and other goose projects in

Though not considered a vital function, since Canadas have used the area before the Game Commission took over control of the area, the flock is also used to attract the first migrants. Veterans Day usually sees the arrival of the big honkers, and some remain until March when they fly to nesting grounds in northern marshes. It is hoped that some of the wild geese will join the resident flock in raising young. Platforms have already been constructed of various materials to encourage nesting.

Although closed to public access during the waterfowl migrations the area offers sportsmen an added bonus in fishing when the honkers are not around. Like the upper feeder streams on other major reservoirs, the channels of the North Platte and Clear Creek provide outstanding catfishing in the spring, and white 50 bass are taken in these waters in their seasonal runs in the river.

Although managing the present goose crop is the major objective, Clear Creek may have an impact on tomorrow's flocks by giving researchers an opportunity to study the birds. Canada concentrations at Clear Creek provide game technicians a perfect opportunity to trap and band birds once the season is over. Age, weight, and sex of a trapped bird are recorded, and once a leg band is put on, the bird is released.

Months, perhaps years later, the recovered bands will provide identification of geese that are trapped again or bagged by hunters. This data will give clues to numbers, group movements, and will help chart continental migrations and movements in the state.

The pressure on the Canada goose increases each fall as he gains prestige as a trophy among hunters. But with food and sanctuary at places like Clear Creek, the Canada goose should be a part of the fall scene in Nebraska for generations to come. THE END

NEBRASKAlandSIX MINUTES TO TOMS

(Continued from page 18)flames. She was almost within touching distance when she stopped, but she didn't give any ground. The deer resumed her stomping and snorting as the squirrel kept rattling away, but she never tensed for that final charge. That doe must have been a left-hander or rather a left-footer for she continually pounded her left hoof against the turf. When she wasn't stomping, the doe whitetail stood with her front leg raised like a pointer hot on a covey.

The minutes were like snails as the doe and I faced each other in this crazy stare down. Then the squirrel tired of the vocal duel and holed up. Slowly, the deer unwound, backed away, flipped her tail in victory, and sauntered off, taking her companions with her. Cecil had watched the whole amazing show.

"Doesn't that beat all?" he marveled. "If I hunt with you for a week, I'll be a steady contributor to "Believe It or Not". First, two turkeys with their heads crossed and now, a face-to-face showdown with a doe. There were a few times I expected you to come bailing out of that blind like a turpentined cat. That deer meant mayhem."

"I was torn between curiosity and fear. Curiosity won, but wasn't that something?" I admitted. "Tomorrow I'm going to get me a gobble bird."

The next morning we went back to the canyons and I came as close to getting a turkey as a man can and still come out empty-handed. It was calm and the gobblers were in a responsive mood. Cecil's first call brought an immediate reply. The torn was mighty close and very interested in our sweet talk, but he was also cautious. We could hear him gobbling and strutting just a few yards away, but he never left the concealing brush. Then he must have spotted me. I heard the rapid staccato of his fleeing feet on the dead leaves and then all was still. That was it, for I had to give up hunting and return to Lincoln.

Cecil was sorely disappointed that I didn't get a gobbler. He urged me to come up for the last weekend of the season. It was tempting, but after that last letdown when I had been so close and yet so far, getting a gobbler didn't seem so all-fired important. I had experienced not one but two once-in-a-lifetime adventures and their memories were far more satisfying to me than the carcass of a turkey in the deep freeze. THE END

THE STEEN YEARS

(Continued from page 35)I have been cussed and discussed, I have stuck to the truth, for only in the truth is there salvation. I didn't come to Nebraska to compete in a popularity contest."

Steen has also tried to develop better use of the resource by encouraging people to hunt harder, and through the cocks-only pheasant season which makes it nigh impossible to overharvest. When APRIL 1970 he came to Nebraska, gunners were taking only 35 to 40 percent of the available roosters. Now they harvest about 55 to 60 percent, thanks to Steen's efforts for a longer season and less stringent regulations.

Hunters now have wild turkey seasons. But, before Steen, many releases of game-farm turkeys were made by individuals and the state and failed. Like other nonmigratory birds, turkeys live in geographical races or subspecies which are best adapted to the environment.

"People can understand why pineapples won't grow in Nebraska," he said, "but they can't understand about turkeys. They were native here, you know, but were extinct by the turn of the century.

"When I first saw the Pine Ridge, I said this is similar to the range of the Merriam's turkey of the southwest. They live in relatively high, ponderosa-pine country and have a remarkable ability to withstand the cold weather. So, why not try them?

"I had a "helluva" fight up there around Chadron and Crawford because they wanted to stock the Virginia turkey from the game farms. But, I didn't want the Virginia cluttering up the strain of Merriam's that might develop.

"Well, nothing succeeds like success. And that Merriam's stocking was the most outstanding success I've ever seen. We stocked 28 live-trapped birds in 1959 and opened the season in 1962."