NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

March 1970 50 cents MYSTERIOUS AIRSHIP SIGHTED HERE ANOTHER FIRST AT LAKE McCONAUGHY DUCK HUNTING WITH BOW AND ARROW THE SOUNDS OF WHISPERING SANDS ED WEIR, NEBRASKA FOOTBALL GREAT

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

The Lone Star isn't lonely anymore

Texas is more than a state. It's a state of excitement. It's also a state of industry. Business. Fashion. Education. Sophistication. Professional sports. You name it. Texas has it. And, right in the heart of all this activity, you'll find Dallas/Fort Worth. And, in Dallas/Fort Worth, you'll find Frontier Airlines. We fly from Nebraska to Dallas/Fort Worth every day. Chances are, you're only a short hop from a convenient connection to a Frontier Arrow-Jet bound direct for Dallas/Fort Worth. To find out more about our convenient service to Dallas/Fort Worth, call your Travel Agent or Frontier. You might just end up deep in the heart of Texas. FRONTIER AIRUNES a better way to fly NEBRASKAlandFor the Record ... BURNING TRADITION

Fire instantly strikes terror in the heart of every living creature. While fire can be the direct cause of death to all forms of animal life, the most far-reaching effects on our wildlife are more subtle.

Why does a landowner or operator deliberately start a fire? There are two main reasons for most spring fires — weed control and "improvement" of the appearance of the land.

Most people who burn to control weeds believe that fire will destroy weed seeds. However, authorities agree that most varieties of weed seeds are actually quite tolerant to fire. In fact, some varieties of weed seeds are actually stimulated to germinate by fire. Weeds cannot be controlled by burning.

Burning to "improve" the appearance of the farm or ranch is usually carried out in conjunction with the so-called "burning for weed control". Most of this burning occurs in roadsides, fence rows, and odd areas around the farm.

Does the unsightly scar left by a spring fire actually improve the land? Exposed soil resulting from burning is subject to severe wind and water erosion. Mother Nature constantly strives to cover bare land with some type of vegetation. If the land is undisturbed, it will eventually be covered with growth called "climax vegetation". This may be native grasses or a forest, depending on topography, climate, and other factors. When an area is burned off, it actually reverses what nature is trying to do.

What effects can this burning have on Nebraska's wildlife? Actually, few wild animals are killed directly by fires. During this period, most forms of wildlife are mature and capable of escaping the threat. However, the indirect loss of wildlife can be extensive. Nature cannot produce when her hatcheries are destroyed.

Wildlife cannot survive without protective cover. In summer and fall, there is normally adequate wildlife cover found throughout most of Nebraska. In late winter, however, adequate protective cover can be rather limited. Protective winter cover in the form of woody or brushy plants is preferred, although a wide range of heavy grasses, brush, and weeds is used and suffices under all but the most extreme conditions.

Winter cover is important to wildlife in Nebraska, but there is an acute shortage of another vital type. It is totally absent in some localities. More important to pheasants and other game than any other is nesting cover.

Good nesting cover may occur in several forms, but the most common is a mixture of grasses, legumes, and forbes (weeds) which stand to 30" high. A hen pheasant requires enough ground cover to protect her and the nest from predators and other mortalities for six weeks or more each spring. As nesting cover goes, so goes the pheasant population.

Perhaps the most tragic thing about cover destruction is that it is mostly unnecessary. The burning is done out of tradition or habit and because the wind is right and matches are handy, not because burning is a good land management practice.

MARCH 1970WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM 5

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

GRAND TOUR-"Our December NEBRASKAland was so inspiring that we decided, with another couple, to tour parts of Dodge, Douglas, and Washington counties one Sunday afternoon. Such a drive is so inspiring. Corn, milo, soy beans in such abundance, and weather unequaled by any place in the United States. The car radio was kept silent. The farms, buildings, and cribs so neatly filled and housed for oncoming winter. If Nebraska's football team doesn't thrill you, take a drive most any place in Nebraska. Both our football and our crops rate No. 1." —Leonard A. Mangold, Bennington.

FAR-FETCHED PHANTOM-"Your story, Phantom of Driftwood Creek is interesting even though a little farfetched.

"You say there are 10 reported and 2 confirmed sightings of mountain lions in Nebraska since 1880. But in 1945, while driving through Clearwater at about 2 a.m., I stopped and took a bucket to the Elkhorn River to get water for my car radiator. After filling the bucket I got up and turned. My flashlight lit up two bright eyes the size of half-dollars. I saw that they belonged to a mountain lion about 20 feet away. I froze.

"After a few seconds, which seemed like an hour, I realized that the big cat was curious—just watching me. Not wanting to run or walk away, which might provoke an attack, I stamped my foot, shook the bucket, and said, 'Scat!' The lion jumped into the river, swam 50 feet to a small sandbar, then turned and looked at me like he was wondering what kind of silly jerk I was.

"I threw a piece of driftwood at it and the lion waded the rest of the river, then disappeared into the trees. I drove back to Clearwater and told the night marshal who looked at me with the same wondering expression as the lion. Two weeks later a newspaper reported a lion at Shelby.

"A barber at Pacific Junction, Iowa, just across the river from Plattsmouth, shot a mountain lion in about 1956.

"In October, 1958, my son-in-law and I saw a mountain lion east of Fontenelle Forest. We told deputy sheriff Mike Cisler about it. He called Dick Wolkow who is now at Two Rivers State Recreation Area. Wolkow took plaster casts of the four-inch prints in the mud. I have seen the lion several times since. Once it walked to within 100 feet of me and watched me fish the river.

"In 1959, George Bilek fost a cow to a .22 bullet. He buried the animal. Several days later the lion dug it up, leaving plenty of tracks nearby.

"I took plaster casts and gave them to policeman Harold Henry in Bellevue." — Lawrence Dokulil, Omaha.

CHERRY COUNTY SIGHTINGS - "The January issue is most interesting and I particularly enjoyed the article on page 48, Phantom of Driftwood Creek. I also read the italicized comment following the article.

"If you are interested in a trip to Cherry County I am sure that we can provide information concerning numerous sightings of puma in this area during the past 15 years —the most recent only 2 years ago and in the same area of several earlier sightings." —Roger Little, Valentine.

HEALTHY ENVIRONMENT-"An article (Reader's Digest, October, 1969) cited south-central Nebraska, composed of an 11-county stretch, as the healthiest spot in America. The reasons given for longevity in this area are varied and inconclusive. In spite of its violent weather, the fact remains that Willa Cather Country holds this unusual distinction which is a glowing tribute to our NEBRASKAland."—Mrs. Gordon Moranville, Bayard.

SINKING SOD—"I just finished reading in the December issue an article, A Lake is Born, by Bess Eileen Day. The first time I read the article I was rather confused about the location of the big cave-in.

"I was born in Sherman County and grew up there. I remember hearing of a man's cornfield sinking. Until three or four years ago it was just a story, though. Then my wife and I went back to Loup City to visit my family. While there we went on a Sunday drive, and the conversation led to that old sinkhole. My brother-in-law took us to the place between Scotia and Cotesfield where an area about a mile long and 1,000-feet wide sank about 100 feet. Trees and grass were growing in the bottom and the land is farmed right to the edge of the sink.

"The article in NEBRASKAland describes a place near Oakdale — so there are at least two good-size sinkholes in the state." — Chriss Obermiller, Gordon.

BOTTLE NOTE-"While working on the Chicago and Northwestern railroad one noon hour, I found a bottle and wrote my name and the year and threw it in the Platte River. Two years later I received a letter from Omaha.

"One other time I found a bottle while fishing, but all it said was, Thrown from Schuyler bridge on Flag Day.' Here, in part, is the letter I received:

"'Dear Billy —We found your bottle with your name and address on August 16, 1948. We can't read the date you wrote as the paper is torn. All I can read is April 18, 194?. My dad and little brother were digging for worms on an island where the Platte and Elkhorn rivers join. We have a cabin there. Many times we threw in bottles but never received an answer...

" T would like to hear from you. Where and when you threw your bottle in. Perhaps one of my brothers would like to write to you. I wonder how many miles your bottle floated. I suppose the floods washed the bottle in and buried it on our island. What do you think?' signed Francis Pistello." — Billy Buchholtz, Morse Bluff.

NEWER MODELS - "I am 94 years old and live at the Linden Manor nursing home in North Platte. I have seen and read a great deal of history. The only things in use today that were made before I was are the telegraph and steam engine. Every other thing we have in modern life has come about in my lifetime. But your story in the December magazine beats anything I ever read.

"I have been up to the Fort Robinson museum and have seen the skeletons of prehistoric beasts and I saw one thing that I didn't believe at first. It was a human skull. But, now I believe it, for this country was pretty well populated when Columbus lit here. Men can estimate maybe within a thousand years or so of those things that took place, by studying fossils, and some times they get very close. They say the fossil bed in northwest Nebraska extending into Wyoming is from 10,000 to 12,000 years old, and I expect that is very close." — John V. Allen, North Platte.

BIT OFF —"You are the ones who are a bit off on Mrs. John Miner Schoer's story about the rabbits in Custer County. I have been hunting in Custer County NEBRASKAland since the 1920's. At that time there were two kinds of jackrabbits, whitetails and blacktails. The whitetail was the larger of the two."— Ed Dreyer, Ashland.

You are right. There are two kinds of jackrabbits, whitetails and blacktails. We were not arguing that point in our January editor's note. What we said is that cottontails and bunny rabbits are one and the same. Jackrabbits are another bundle of fur. — Editor.

NASTY WORD —"Boy, are you guys going to catch it now from all of the blue-noses who wrote to complain about the pictures of the beautiful Nebraska hostesses. Wait till they see the nasty word that's on the snowmobile in the January issue."—Harold C. Kleckner, McCook.

BOTTLE FIRE-"Warning! A bottle of water can start a fire. We found this out the hard way this fall, and almost burned up the pickup truck we were driving.

"We always carry a bottle of water for the dogs and ourselves. On this occasion, we placed the bottle inside of an open carton, along with some crumpled up sacks that we were going to use to hold our birds. About 11:30 a.m., we parked the truck, facing north, exposing the top quarter of the water bottle to the sun. We had walked the fence about a quarter of a mile. When we looked back, we saw smoke coming from the truck. The carton had completely burned up, together with the papers, and had spread through the loose hay in the truck. Had this been other than a steel body truck, it certainly would have done damage to the vehicle.

"My brother has experimented with this same situation since then. In each case, the carton, hay, or papers have been set afire. The water bottle was full and, we presume, since none of us smoke, that the bottle of water acted to magnify the sun's rays. This is the first time anything like this has happened to us, in our 40 years of hunting, but then there is always a first time for everything, I guess." — Fred E. Bodie, Lincoln

WHIMSICAL SPRING by Miss Lucille Patterson Lincoln, Nebraska I herald the coming of whimsical spring when winds softly whisper among elm and pine. Green tufts of grass steal across a dewy hearth of sun-dappled wedges of shiny black earth. I cherish the gay song the robins sing, as they perch on blossoming bush and bough. Spring is here! Spring is sunshine, laughter, and cheer. Facetious......Sultry...... Spring is cloud and rain beckoning with splashing fingers on my windowpane. MARCH 1970By popular demand... 1970 NEBRASKAland in bound volumes!

Readers have asked for it, and now it's happened. For the first time, 12 exciting issues of NEBRASKAland magazine will be available in a single volume. To be attractively bound in hard cover, the colorful books will sell for just $10. They will make ideal gifts and welcome additions to any home, library, or collection. Supplies will be limited to those who make advance reservations, however. So, get your order in now. The books will be available about December 15, 1970. YES! Reserve my bound volume of NEBRASKAland magazines for 1970. My $10 is enclosed Name Street City State Zip

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . PINTAIL

Whether hunted or watched, this duck will quicken pulse. Spring courtship show is sightseeing must

THE MERE THOUGHT of wild waterfowl is enough to quicken the pulses of a good many sportsmen. Imagination may first conjure up images of the gaudy mallard, but second reflections often create a mental picture of a slim, trim, handsome drake with a linear white stripe on his long, slender neck. He is a pintail, but in some areas he is known as a sprig or sprigtail.

Scientifically, he is known as Dafila acuta tzitziboa. But, whatever the name, these birds create quite an impressive sight as they rise from a field or marsh in late winter or early spring. Exceedingly wary, they have frustrated many a hunter as they decoy to a set of blocks about two gun ranges high and after a third and fourth pass disappear into the distant horizon.

These birds prefer the flat open spaces of the short-grass prairie and meadow for nesting, after an awe-inspiring courtship flight that is a picture of speed, and grace, and maneuverability.

The drake chooses the actual mating territory, usually a small pothole or the bare beach of a bay of a larger water body. The hen selects the actual nest site on grassy flats of dry land, sometimes as much as a mile from water. The nest is a shallow, scooped-out hollow with a lining of grass and down. Clutch sizes range from 6 to 12 eggs, averaging about 9. Incubation begins when the last egg is laid and takes 22 or 23 days.

Pintails are early nesters. In Nebraska, the first ones start appearing about the third week in May, along with some early mallard broods. Their primary breeding range is the pothole country of the Canadian prairies, but they have one of the most extensive breeding ranges of any duck. Pintails avoid the woody parklands and lakes north of the prairies, but utilize the more northern tundra of the Yukon and Alaska and even the marsh country of Siberia. Over the past 14 years, pintails have comprised about 6 to 7 percent of Nebraska's breeding ducks, with a population averaging 13,600. Populations have ranged from a low of 4,400 in 1965 to 32,000 in 1958.

The young are among the faster maturing species of larger ducks, and the first few days of July find the earliest broods on the wing. Their flight capability develops fast, and they begin moving out of their nesting area in all directions. By the time the hunting season begins, 8 some have moved northward as far as southern Canada.

Migratory habits are characteristics of northern breeding ducks, and the pintail migrates, too. But, he does it differently than the more conventional species. Most ducks move south and southeasterly from the breeding grounds to their wintering areas. Although some Central Fly way pintails do move from northern latitudes across Nebraska to the coast of Texas and into Mexico for the winter, the bulk of them move to the West Coast and winter in California and on the west coast of Mexico.

In late winter they begin the first leg of their journey to the breeding grounds by moving easterly across Mexico to the Gulf Coast and then northward through the Central Flyway states. They, along with some mallards, are the first migrants, arriving in Nebraska by mid-February and even earlier in some years if the winter is mild.

Severe weather will frequently push this early vanguard back south to more moderate conditions. But they keep the pressure on winter's •northerly retreat, accounting for the large concentrations bunched up just south of winter's icy grip. Their stay in the state is rather short, and the mass has moved on by late March. These spring spectaculars are made up mostly of drakes, and in the years prior to our recent depressed duck populations, their numbers exceeded the million mark in the Platte River Valley and basins south of it.

In addition to the attraction provided by the large concentration of waterfowl, spring is also the time that mate selection occurs. The aerial-courtship show that accompanies the numerical spectacular merits a sightseeing tour.

In spring, the females are outnumbered several times over, and the drakes in their finest breeding plumage put on a rigorous display of neck stretching and antics to reveal all their charms. She seems to ignore all this attention and takes to the air. The chase by six to ten males begins one of nature's most fascinating aerial shows. She leads her pursuers in tight formation in highspeed twists and turns, shooting to great heights and power-diving down again. The formation is so tight at times that the wing tips are flapping together.

In the fall, observers do not see the large numbers that occur in the spring, but the pintail is one of Nebraska's more abundant visitors. He is again an early migrant, arriving in substantial numbers in mid-to-late August. Peak fall flocks occur early in October, and most have left by late that month.

Pintails are classed among the large ducks and are a welcome addition to the hunter's bag. They rank close to the mallard as table birds. Nebraska's average harvest of this species over the past 13 years is 16,500. The short season and small bag of 1961 limited the kill to less than 5,000. The largest take occurred in 1957, when 46,000 were bagged.

A streamlined, distinctive bird, the pintail occupies a place of special esteem with most Nebraska outdoorsmen. THE END

NEBRASKAland

CLICK FOR HELP

BUSINESS AS USUAL was the order of the day as I worked my way through western Nebraska's incredible Sand Hills. Bunchy, gray clouds shrouded the choppies that chilly mid-March day back in 1967, and as a newcomer to the area I was really amazed at the vastness of the hills. Trouble couldn't have been farther from my thoughts.

A game biologist with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, I had recently been transferred to Alliance, and was spending the day making a wetlands survey in Sheridan County. This type of survey involves the inventory of potholes and lakes and collecting a variety of data about them.

Although new to the area, working from a topographical map, I always knew my exact location. I had just checked out a shallow marsh-lake and was rounding an unusually large hill when I made a big mistake. I hate to admit it, but I was gawking at the landscape rather than paying strict attention to the treacherous Sand Hills trail. "Ker-slam", I drove directly into a blowout. Carved out of the sand by the wind, blowouts range in size from huge craters to relatively small holes. The one I happened into was just big enough to put me in a jam.

I climbed out of the car and evaluated the situation. It didn't look good. I got back in and tried to work the car out, but only managed to bury the back wheels in the soft sand.

"Oh Boy!" I thought. It was about 3 p.m. and I was going nowhere fast. I got a shovel from the trunk and went to work digging. After about 20 minutes or so, I pretty much had the sand cleared away. Once more I climbed in the car and tried to get out of the hole. And, again, the soft sand pulled the car tighter into its grip.

After fussing about in this same manner for another 45 minutes, I decided to abandon the idea. Somewhat embarrassed, I picked up my radio microphone to call the Alliance office for help.

Clicking the on button, I called the office. But, there was no answer to my call. I tried again and again, but always my calls went unanswered. From the map, I could see that I was about 20 miles north of Lakeside. I couldn't figure out why the office wasn't reading my signal. Then, it hit me. The large hill that I was stuck next to was blocking my transmissions.

Now I was really disgusted, especially with myself. The map showed 10

Darkness was only a few minutes away by now. I had a decision to make. I had passed a house on the trail about six miles back that I knew for sure wasn't deserted. Should I try to backtrack to it in the dark or wait until the next morning? I decided the chance of getting lost wasn't worth it, especially since I was a newcomer to this territory. I had heard many a grisly story about folks who lost their way in the hills, and by no means was I a survival expert.

When I got back to the car, I tried the radio again. Still no response. The sun had now set, and the day's leftover cloud cover transposed the dark of the evening into an inky impenetrable blackness. Coyote yips and a cold prairie wind made me happy I chose not to walk.

I was just sitting in the car cursing myself for goofing up when my radio sounded off. I was startled at first, then glanced at my watch. It was nearly 8 p.m. I figured my wife had someone out at the office trying to call me.

I received the message perfectly, but I knew they wouldn't hear me. In low hope I picked up the microphone and answered. No luck. I tried to answer again. A voice over the radio then told me that they could pick up my clicking but that was all.

"If you are all right, answer with two clicks. Use only one click if you are injured," said the voice over the radio. I replied with two clicks.

Then, using this same technique of affirmative and negative answering, headquarters tried to locate me. However, when asked which direction I was from certain landmarks, I was helpless because of my unfamilarity with the area. About all I NEBRASKAland could do was answer "yes" to being north of Lakeside.

The next three or four hours were extremely anxious ones, as I sat waiting for help. They were also frustrating. I could hear the searchers talk to one another over their radios. And, at one time one of the search units was about a mile from me. But, that crazy hill still blocked my transmission to the radio tower leaving me helpless.

About 11 p.m. the searchers still hadn't found me. I guess there's a lot of country north of Lakeside. A few minutes later the radio dispatcher told me that the airplane was going to be called out for the search. By this time I was really angry. All this trouble over me, and I really was in no danger at all.

It seemed like hours before I heard an airplane in the distance. I grabbed my microphone and immediately made contact with pilot Leonard Spoering. The airplane-to-single-unit communications is set up so that a radio tower is not necessary for contact. It was sure good to talk to someone again without clicks.

A few minutes later a set of headlights was rumbling down my trail. Before I knew it, three men came running full speed up to the car. I stepped out and greeted them in a happy and embarrassed voice.

"You're all right," they all shouted in unison.

"Fine," I said. "I told you I was all right."

But, I really hadn't. When they had asked if I were o.k., and told me to answer affirmative with two clicks, I did. But, apparently the transmitting tower failed to receive one of my clicks, sending only one click to headquarters. Everyone had thought I was injured.

My rescuers were Game Commission personnel Ken Johnson of Lincoln and Harvey Suetsugu of Alliance and the rancher whose land I was stranded on. After we figured everything out, it was unanimous to head for home. It was about 2 a.m. A chain was incorporated to pull my car out of the hole, and an hour later I was home comforting a worried wife.

The next few days I was subjected to considerable ribbing from my coworkers. I deserved it though. I made it a point to learn a few tricks about getting unstuck from the sand, and today a similar episode might not turn out the way it did then. In any event, I haven't lost an ounce of respect for the massive Sand Hills. And, one thing for sure, whenever I'm driving off the beaten path in the hills I always keep both eyes on the road ahead. THE END

MARCH 1970UNION LOAN & SAVINGS ASSOCIATION

NEBRASKAland's MONEYIand 209 SO. 13 • 56TH&O • LINCOLN 1716 SECOND AVE. • SCOTTSBLUFF

NEBRASKA'S UFO'S

From all over the state have come reports of strange vehicles in the sky, some from as far back as 1897

RETURNING HOME FROM a prayer meeting in Inavale, Nebraska the night of February 6, a group of people suddenly saw a very bright light passing directly overhead. The source of the light, they found, was an airship, conical in shape and perhaps 30 to 40 feet long. The craft had two sets of wings on each side, and a large, fan-shaped rudder at the rear.

At the same time, a "most powerful" light was evident for several months in the skies near Hastings, and so people assumed there was some connection. Also during that period, a craft fitting the same description was spotted over Omaha by several witnesses, including a group of Ak-Sar-Ben members. They said the airship was about 90 feet long, eliptical in shape, with wing-like projections fore and aft on each side. On the forward end was a bright light which was evidently used as a headlight. Reports of the same vehicle also came in from Kansas City and Denver.

The year was 1897, the airplane was still in the future, and reports on this "mysterious airship" were probably the earliest recorded UFO (Unidentified Flying Objects) sightings in the state. The descriptions of the airship bring to mind a dirigible, but even that explanation is highly unlikely. Unlikely because the first dirigible was not developed until 1884 in France, and it was many years before they were capable of crossing the Atlantic. Besides that, the United States didn't even have a model capable of worthwhile flight. Another theory was that the airship was really a kite, but that too is unlikely because the object was spotted in several different areas.

Further evidence that something peculiar was roving the midwest skies came from a farmer in the neighboring state of Kansas. He apparently observed the same craft that was seen in Nebraska. His account resembles a science-fiction thriller.

The farmer, his son, and his hired man were attracted to a field near the farmhouse one evening. There, slowly descending from the sky was a huge airship. As the three men drew near they saw a carriage made of glass or another transparent material underneath the 300-foot craft.

In the brightly lighted interior were six of "the strangest beings I ever saw. They were jabbering together, but we could not understand a word they said."

Upon sighting the three men below, the spaceship crew turned a bright light on them, started the power for a 30-foot turbine wheel, and the buzzing vessel rose. At an altitude of 300 feet, the ship paused and hovered over a two-year-old heifer which was tangled in the fence. The trio went to the animal and found a cable tied about its neck that ran up to the craft. Unable to cut the cable, the men cut the fence, whereupon the vehicle ascended, lifting the heifer with it.

More recently, Nebraska was one of several states included in a blanket of sightings of UFO's. The rash of reports began in August of 1965 when authorities at Wichita, Kansas said the Weather Bureau tracked several UFO's between altitudes of 6,000 and 9,000 feet. Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma was said to have tracked 4 unidentified aircraft on its radar screen at one time, estimating their altitude at about 22,000 feet. During the same influx of sightings, reports came in from Sidney, Grand Island, Broken Bow, and other localities in Nebraska. Captain Les Beekin of the Sioux Army Depot at Sidney said he saw objects three nights in a row, as did four other guards who were on duty at the plant.

"They looked like a Naval cruiser going through the sky," he said. "There were one large and four MARCH 1970 smaller objects, flying in a diamond formation, and they appeared white."

In the 1940's, 50's, and 60's the story was the same. From York, Nebraska City, Alliance, Blue Hill, Fairbury, Oshkosh, Ainsworth, Valentine, Gordon, Nelson, and dozens of other sites came reports of lights or airships. A few were admitted hoaxes, some were doubtless illusions and mistakes, but the others?

One day in 1957, jets of the Nebraska National Guard scrambled to intercept a UFO sighted over Lincoln by the crew of a passing B47. Because it was nearly overhead, the radar operator wasn't able to zero in on it, but pilots of F84's were sent aloft to intercept. They were incapable of attaining the altitude of the "thing", however, and could climb to only about 5,000 feet below it. One pilot, when asked its size, answered that it was "as big as hangar No. 2".

The object still remains as an unknown because no one was able to get an exact "fix", but it was a large, silvery globe with a smaller rectangle below. The object may have been a weather balloon because it took 2 1/2 hours to cross the sky. But, the fact remains that it was a UFO.

Many factors can account for sightings. A high percentage of the objects seen are probably of natural origin, either terrestrial or celestial. This has long been the claim of astronomers, investigators, and other "nonbelievers". Officialdom, in fact, explains away all but two percent of the total sightings by attributing them to planets, bright stars, birds and insects, reflection of lights off clouds, various gases, the Aurora Borealis, pranksters or hoaxers, hallucinations, powerline corona, and several others.

Still, there is that two percent with no explanation. Despite intensive study, questioning, and even ridicule, some people's stories cannot be shaken. These few phenomena give the believers something to hang onto with tenacious determination, and form a basis for building other reports upon.

Nebraska has had its share of phenomena. Hundreds of individual reports appear on the books and

in the papers. They originate in all parts of the state,

although the eastern portion, with its greater population, accounts for the bulk of them. A sampling of Nebraska incidents is representative of those from other

13

For example, how is the case of Herb Schirmer, a police officer in Ashland on December 3, 1967, explained? He was making a routine patrol that night, and about 2:30 a.m. found a UFO hovering 8 feet over the highway south of town. He stopped about 40 feet away from the object, which was shaped "much like a football" with a sort of flattened base and with a cat-walk and a row of porthole-type windows around the center.

The width, he estimated, was about 20 feet and the height from 10 to 14 feet. A sound similar to a pulsating siren was evident. Then the vehicle lifted about 50 feet into the air, emitted a huge, red-orange beam of light, and disappeared amidst the siren noise. "There was no smell, smoke, or exhaust," Schirmer noted.

No traces of the craft were found at the scene later. Several months afterward, Schirmer went to the University of Colorado to see if he could add anything to his experience while under hypnosis. A professor at Colorado was working under a federal grant on an intensive study of UFO's. For one thing, Shirmer had been unable to account for a half hour, from first sighting at 2:30 until 3 a.m. when he next realized where he was. Under hypnosis, the episode became even more involved, for he related details he had not mentioned before, such as an apparent telepathic or real conversation with one of the "beings" on the craft. That "being" promised to return within the year.

Almost a year later, on November 30, 1968, Dean Edwards of Lincoln did, in fact, report seeing an object 14 about 9 p.m. near Ashland while he was driving on Interstate 80. He said the thing looked like a beacon circling about 200 or 300 feet above the ground. It was round and flattened, made no noise, and was unlike anything he had ever seen before. With him at the time were his wife, brother, and sister-in-law.

Doubtless a good many such incidents are nothing more than unusual or normal occurrences seen under abnormal circumstances. Excluding the possibility of someone's practical joke with a home-made craft, the alternatives seem to be either pure imagination or actually seeing a ship. It is possible to confuse dreams with reality under certain conditions, but it is also easy for non-witnesses to dismiss all such stories as hysteria, make-believe, or pure and simple mistakes. Persons having run-ins with alien craft, however, are not normally of questionable integrity.

In the words of Dr. J. Allen Hynek, chief scientific consultant for the Air Force, "The surprising thing is the level of intelligence of the observers and reporters of UFO's —certainly above average, and in some cases decidedly above average. The typical witness is honest and reliable."

Among possibly hundreds of Nebraska sightings are the following:

Earl Moore and Ed Rowley of Lincoln saw two white or silvery objects over downtown Lincoln one afternoon in 1952 while they were crossing the street. They estimated the objects as 100 feet in diameter.

Several witnesses in Lincoln sighted a strange thing on October 1, 1952. They reported from Waverly - a white flash of light about 10 yards long, with a ball of orange fire at one end and blue-yellow exploding fire at the other. The same description came from other NEBRASKAland couples who saw the thing from Pioneers Park on the opposite side of Lincoln.

Two Douglas County sheriff's patrolmen, Sgt. Dan Lang and Joe Golden, reported a bright, green-blue object trailing off to an orange glow, moving across the sky at 4:15 a.m. on May 28, 1966. At about the same time, an employee at Western Electric in Omaha saw the same object while he was on lunch break.

On August 10,1952, a crew of Douglas County employees working on a bridge saw a 'round puff of smoke" streak across the sky at 12:18 p.m. The puff traveled at great speed, being visible only for about 15 seconds.

A formation of a dozen white lights was seen in the night skies in the Oxford, Orleans, Arapahoe area in south-central Nebraska by several witnesses on August 1, 1955. They believed they were not regular aircraft.

Five college students in Lincoln, from several locations, reported on April 16, 1966, that they saw an oval-shaped craft, unlike any airplane, maneuvering in the skies over Lincoln. They watched it make a circular flight. It made no sound, was tremendously brilliant, and changed colors. Its size was described as being like a spool held at arm's length.

Two Lincolnites, returning from Colorado on October 14, 1959 spotted a flying object near Pleasant Dale, and they stopped at a service station on Cornhusker Highway in Lincoln to point the object out to station attendants. The men said they first heard a siren sound, then saw a light in the sky which they at first thought was a meteor.

"It was the biggest we ever saw," they related, and compared it with an arc light. They followed the light nearly to Waverly where it disappeared behind clouds.

Descriptions of flying objects are fairly universal, usually being saucer or disc-like or resembling cigars or dirigibles. They are almost always accompanied by bright, flashing, or colored lights, but they are about divided as to being silent or making noise. Except for a case near Hastings in which a California man claimed to have conversed and traveled with aliens in their spaceship, Officer Schirmer's case is probably the only one in the state involving direct confrontation.

In the Hastings case, the man involved was committed to a hospital for examination and treatment, and officials shrugged it off as hallucinatory. After his release, the man traveled widely, accusing investigating officials of persecution, bungling, and ignorance.

Arguments against the existence of flying saucers or whatever they are called, are quite impressive, however. The U.S. Air Force compiled just about 12,000 sightings between 1947 and 1969, of which all but just over 700 were attributed to natural or explainable sources. One argument supporting the Air Force contention that people are merely "seeing things" is provided by the vast network of full-time sky watching. Virtually every inch of space above North America is scanned continuously by radar operated by the Air Defense Command.

Further support comes from the Smithsonian Astrophysics Observatory, which has set up automatic cameras in the midwest, including four cameras in Nebraska. Covering essentially the entire sky and designed to photograph celestial objects, the camera system has not captured anything the researchers did not understand.

Carl Sagan of the astronomy department of Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory came up with an interesting statistic. He noted that even if one million other planets in our galaxy had intelligent life, each capable of launching spaceships at random, one annually each, and earth was the target for all of them, only 1 would reach earth every 100,000 years.

Despite all logic, though, many reports are difficult to dispute. Whether it is wishful thinking or faith in their fellow man's beliefs, many people tend to believe some of the tales. Disregarding hoaxes and illusion, there are cases which sound authentic.

Unfortunately, there are enough practical jokers, who have admitted constructing "flying saucers" to give people something to talk about, that investigation has been greatly hindered. Because nothing has ever been turned up of a suspicious nature, the Air Force recently closed down its "Project Blue Book" office — the facility assigned to catalog UFO reports.

If any of the "contacts" with alien craft have been true, it would be difficult to prove it from among the many false ones. Human nature being what it is, UFO sightings will continue. Reports of lights and craft in Nebraska will probably be among them. Perhaps, after all, Nebraska's tranquillity is an attraction for beings other than humans. THE END

ANOTHER "FIRST" AT BIG MAC

A young swimmer had conquered our largest lake. Now we had a new challenges 90-mile hike around it

MY DAUGHTER JODI and I stood silently at the south end of Kingsley Dam. We looked out across Lake McConaughy's many miles of blue, restless water and were bathed with the warmth of a clear, August morning. Gulls dipped for breakfast, while white wisps of clouds arched overhead under the urging of a southern breeze. It was a picture-postcard setting, but we were in it —actors in a scene of unbelievable beauty and peacefulness. An automobile horn, though, ended our reverie.

"We'd better get off the road, Jodi," I chuckled, "or we might not finish this little hike."

Our "little hike", however, was not so little. Already we had walked nearly 45 miles. Our goal was to go all the way around Lake McConaughy, a distance of some 90 miles. Big Mac, which has been testing boaters, swimmers, and fishermen since it was created 30 years ago, now gave us a challenge. No one had ever walked completely around Mac, and that's what we were trying to do. Kingsley Dam, at which we found ourselves that Wednesday morning, marked the halfway point.

As we began the three-mile walk that would take us from one end of the earth-fill dam to the other, I had a chance to think about the first four days of our adventure, and why it now felt so good to be finally going across this mammoth structure.

Our journey began on Saturday, August 16, 1969, at 10:45 a.m. I know the precise time because I carefully recorded all the important incidents of our trip as they happened in a small, red, spiral-bound notebook that I kept in my shirt pocket. Lewis and Clark may have kept better journals, but I figured that later we might like some reminders about mileages and events. Thirteen-year-old Jodi originally had intentions of keeping a diary, too, but every time we stopped to put down some notes, instead of putting words in her notebook, she would start drawing pictures of horses. Horses, especially appaloosas, are Jodi's first love, and any chance she got added another sketch to her growing collection.

My wife, Dorothy, drove us from our home in Bridgeport to Lake McConaughy's southwestern shore. She was confident that we were well prepared with both supplies and outdoor experience, but this was our first try at extensive hiking and backpack camping. And despite Dorothy's cheerful send-off, we knew as well as she did that this trek wouldn't be a picnic. There was, as Dorothy had told a friend in Bridgeport, "nothing but packs between them and the outdoors."

Those packs held a lot of useful gear, and our years of family camping helped us choose the right equipment. For preparing meals we had a one-burner stove with a supply of gasoline, a cooking kit, and a few necessary utensils. We also had plenty of food along. Some of it was canned goods but most of our provisions were of the powdered-instant variety. The majority was in my 50-pound pack. Jodi had 35 pounds in her pack, but little of it was food. We hadn't planned it that way, but I had to laugh when my daughter realized that as we ate each meal, my burden would get lighter and lighter.

Other gear consisted of extra clothing, a first-aid kit, and a folding saw. Sleeping bags hung beneath the packs. Our two ponchos, besides their rainwear duties, would be used at night to form a tent. A portable radio and other odds and ends completed our outfit for this "mini-expedition".

As we stepped out, the two of us were full of energy, and the weight on our backs seemed light. The lake, our silent challenger, was to the left as our unusual convoy headed east. The trek began on sand, but as we 16 were trying to follow the shoreline as much as possible, we faced a variety of terrain, including rocky hills, grassy slopes, and muddy shores. The idea of pacing hadn't been given much thought, and before long we found that we were pushing ourselves too much. We had begun by walking for 55 minutes and then resting for 5. Longer breaks later proved valuable.

After three miles of walking, our duo dipped into Dank worth Canyon and continued along the shore. Despite being right on the beach, we got some shade from nearby cottonwoods. Lunch break came just before noon. Our fare might not have tempted a gourmet, but the bean soup, potted meat, crackers, raisins, and candy bars satisfied us.

Many miles slipped by that afternoon, and evening found us at Eagle Canyon, known to some as Eagle Gulch. After setting up our poncho-tent on the sand beach, we had a light dinner. Before leaving, we had decided that we would have something hot each meal and we pretty well stuck to that decision.

That night the wind came howling across the lake, and a couple of times I thought for sure that our shelter would blow away. Additional discomfort came in the form of hordes of pesky mosquitoes. But I soon fell asleep, thinking of the course of events that got us here in the first place.

I guess the idea for this wild scheme was conceived three years ago. Our family had gone to Lake Mac almost every year with our camping group, the 4-Fun Family Campers. That particular year, beachcombing was the favorite pastime and arrowheads the preferred booty. We would head up the shore and then back-track to the campground, looking for relics of those Indian campers of the past.

"Wouldn't it be nice," Jodi mentioned, "if we didn't have to retrace our steps."

"You bet," I countered, "but how could you do it without covering the same places twice?"

One thought followed another and we decided that it would be fun to someday go all the way around the lake.

I had gone on outings with my son, Kenny, away at Chadron State College, but now I wanted to make a jaunt with my daughter, Jodi. Soon to enter the eighth grade, she was at an age where hanging around with your parents loses some of its appeal. I knew that before long she might not be interested in going along with her old dad, so when we had the chance this summer to give the hike a try, we couldn't pass it up. I took annual leave from my job with the Soil Conservation Service, allowing 10 days for the hike. I wasn't sure we could pull it off though, no matter how much time there was.

Reveille was at 6 a.m., and to start the day I fixed some instant oatmeal, coffee, and hot chocolate for Jodi. That morning, we spotted a big buck in some trees. To us, he symbolized the freedom and solitude that we now enjoyed. Catching our scent, he gracefully leaped through the woods. There was a lightness to our steps as we went on our way.

During the summer, the water level of Lake Mac is lowered, exposing more of the shoreline. Sandy areas stay pretty firm, but other spots get really muddy. When our boots got loaded with the goop, we took to the higher ground. Up on the hills we skirted a pasture.

"Those cows are just as curious as anyone else," I mentioned to Jodi, as their wide eyes followed us as we strolled past.

"I'm just glad they can't say what they're thinking," Jodi replied, knowing that she and her escort were the (Continued on page 52)

NEBRASKAland

THE COLLECTING CRAZE

Acquire two and you have an all-important fad

PEOPLE WILL pick up anything. If they acquire two of it, they have a collection. Then the idea is to get as many kinds of the same thing as possible. Watches and wishbones, dolls and decoys, baubles and bonnets, wrenches and spark plugs, all are collecting hobbies.

People have been acquiring things since the beginning of people. Somewhere in prehistoric times early man began picking up pretty stones or shells, because they satisfied his simple aesthetic sense. Besides, he thought, someday they might be useful. He proudly displayed his collection to someone else. Soon his stones or shells became tradable for his other wants, because someone else was trying to complete a set.

While there are rock collectors and shell collectors today, hobbies have become diversified along with the rest of civilization. For example, Esther Jefferson in Sutton gathers wishbones. She has about 3,000 of them displayed in her office at the Sutton Motel. On the other hand, Dr. C. H. Eisner of Crete assembles antique cars. He has about 14 of them, all in perfect running order.

And that brings up another way collecting has changed. Once man lined up his parcel of pretties in his cave and admired it. Today, many people work actively with their hobbies, like Dr. Eisner who is largely his own mechanic.

R. H. Hockaday of Hastings, is a rock collector, but

not of the old kind. His delight is in bringing the inner

beauty of rough stones to their polished surfaces. His

19

Today people proudly spend hours whipping their collections into shape. But once hobbies had a little less prestige. When simply making a living was a lifetime goal, they were luxuries of the leisure class. A common man who hoarded things, besides money, was a lazy slacker. Today, a hobby is a status symbol. And clock collecting is one of the more prestigious hobbies.

Paul Thompson of Lincoln is a member of the clock cult. His father is, too. It's a family tradition. Paul specializes in double-dial calendar clocks, because "these days you have to specialize."

Once, when he was a novice, he bought all kinds

of clocks. He went to garage sales and bought antique

clocks for $10 or $15. Now, however, people have become antique conscious and prices have skyrocketed.

Today the craze is no longer an individual effort.

There are collecting clubs and hobby shops that cater

to the collector's whim. Antique shops are a good source

to help build the hobby of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Cowling of

20

NEBRASKAland

MARCH 1970

21

Lincoln. They're novice insulator gatherers, but they

like to go primitive and pick up their own insulators.

Lincoln. They're novice insulator gatherers, but they

like to go primitive and pick up their own insulators.

"They're kind of fun and kind of silly," Mrs. Cowling says. "There are many shapes, and sizes, and colors. There are types that are common to different areas".

Once, collecting was just a whim. Today it may still be just a frivolous whim, but some collectors are less romantic than serious. Mrs. L. G. Beers saves dolls. From china (godey) dolls to tin-head dolls, she costumes them and cares for them. Once little girls' companions and babies, the dolls have been gathered now in a classic fairy-tale world where they are being preserved for future generations.

At the other extreme is a Sand Hills boot collection. Along a lonely fence line between Bucktail and Whitman is a string of old, weathered cowboy boots resting on the fence posts. No one claims the bunch of boots. It is just worn-out footwear that one cowboy used to "decorate" the fence. Now it is tradition for ranchers and riders to "hang up their boots". There are women's boots, children's boots, and even a pair of "tennis" boots.

And people will collect just about anything. Nebraskans amass antique furniture, artifacts, and coins. There are collections of old machinery and cookbooks, recipes and pens, souvenir plates and matchbooks. Phillip Dowse of Comstock stockpiles wrenches. The hobby includes the variety of shapes and sizes available. "But," he said, "when I want to use one, I can never locate the appropriate kind."

Some fads are common and some not-so-common. Some are serious and some not-so-serious. But common or rare, serious orfrivolous, collections add some color and variety to NEBRASKAland. THE END

HE CAUGHT MASTER ANGLER BLUEGILL

How does Corky Thornton always bring home certificate winning fish? He knows that important third ingredient for success

HOW DO YOU catch a Master Angler-size fish? Simple —know where to fish, know how to fish, and fish a lot. How do you catch two Master Angler fish? Just as simple —more of the same.

How then did Calvin "Corky" Thornton of Valentine take over 300 Master Angler-size bluegills through the ice last season? There is no magical formula. Corky knows how and where to fish, and he spends a lot of time on the ice.

Born and raised in Valentine, he found the best fishing spots by dangling a line in nearly every stream, pond, and lake in the area. He has studied angling since early childhood, and as owner of Cork's Bait Shop for the last 17 years, he has made it his business to know where the fish are biting and how to catch them.

Corky doesn't know how many fish he caught last winter, but estimates his bluegill take at somewhere around 2,000. A stickler about wasting game, he cleaned them all and gave away what he and his family didn't eat. How many of the oluegills were over the one-pound qualification for Master Angler certificates? Corky didn't weigh them all but figures that half of the fish were close to a pound and is certain that several hundred would have made the grade.

Corky heads for the water or ice whenever he gets a chance. On December 19, 1969, it was shortly after 9 a.m. when he drove south out of Valentine on U.S. Highway 83 toward the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge for his first day of ice fishing in the new winter.

A cold snap the previous week had iced the lakes and whetted Cork's appetite for fish. He knew the odds were against his early season outing, for he had taken most of his big bluegills in mid-to-late winter.

About 28 miles south of town he swung off the highway, bumped across a cattle guard, and proceeded west on the narrow refuge road. Minutes later he arrived at Dewey Lake.

Area fishermen had been taking good numbers of perch at Dewey during the past week and Corky considered stopping. Pelican Lake, however, lay five miles to the south and it was there that he had caught most of the certificate-size fish the previous winter.

"Pelican may not even be frozen," Corky thought as he turned (Continued on page 60)

DUCK WITH A BOW

With smaller bag limits, shorter seasons, and more gunners in the field, we find a "new" hunting challenge

THE BIG FLOCK of greenheads appeared high in the southeastern sky. Highball calls swung them around and now they circled just out of range over the decoys. Then from upstream another call rang out. The big ducks climbed and headed upstream in answer to the call.

'There they go again," muttered a hunter to his partner as they watched the ducks wing upstream, circle twice, and set their wings to drop in. Then, just as they appeared ready to land, the ducks flared for no apparent reason. Towering, they disappeared into the northern sky.

"Those guys upstream must be crazy," one of the hunters said, watching the mallards fade into dots. "They've been calling in one flight after another all morning and haven't fired a shot."

The puzzled hunter was far from right. Maybe we were a little crazy and any normal duck hunter might logically have questioned our offbeat approach, but we had been shooting at every duck within range. Our weapons were bows and arrows.

The hunt had originated early in the fall when Steve Kohler, a NEBRASKAland photographer, suggested that ducks could be taken with a bow. I had done some bow hunting, so the idea interested me but I was skeptical. The 12-inch circle of a standing deer at 30 yards was tough for me and the chances of hitting a duck in flight seemed pretty remote.

Steve, an ardent bowhunter and a member of Lincoln's Prairie Bowmen Archery Club, insisted that it could be done.

"I know a couple of guys in the club who would be interested and I think we ought to give it a try," he said.

"I'm game, but we'll have to have a good blind where we can get lots of shots at ducks as they're coming in," I answered. Steve assured me he knew just the spot, a blind on the North Platte River near Bayard.

It was the second weekend of the High Plains Experimental Duck Season before we were able to get away for the hunt. Steve and I drove to Bayard with 26 Herb Hull, a Lincolnite employed in the printing division of the University of Nebraska. Herb has bow hunted for 10 years, concentrating mainly on small game. He had taken ducks with a shotgun, but had never tried wing shooting with the bow.

A full schedule of appointments prevented the fourth member of our group from accompanying us on the long drive out. Dr. Ben "Doc" James, II, a Lincoln dentist, flew in to join us that evening. Doc's archery trophies include deer, a 250-pound Russian boar, and a bear. Like all the rest of us, Doc had taken ducks with a shotgun but was new to archery wing shooting.

Freezing, wind-driven rain greeted us on the first morning of our hunt. A thick layer of ice glazed the road and made the drive to the blind, west of Melbeta, an experience in itself. We arrived shortly after 7 a.m. and were encouraged by a sky full of mallards. Shooting time was 7:18, so we quickly put out the decoys and headed for the comfort of a covered, four-man blind.

There we encountered the first of our problems. While the sunken, flip-top blind was ideal for shotgunning, there simply wasn't enough room to shoot a bow.

"I guess we'll just have to take cover outside around the blind," Herb said as we clambered back out into the wind-driven rain.

Cover was scarce around the blind, but we all managed to find a little brush to hide behind. It was three minutes before shooting time when four mallards landed among the decoys. Doc gave Steve an approving nod as the ducks swam up for closer inspection of the fakes. All of a sudden the greenheads decided something was amiss and beat a hasty retreat.

At 7:18 Steve began calling. Our first customers were five big drakes accompanied by a lone hen. They came in high, out of the southeastern sky, made several swings, and dropped down. Then, a lone drake peeled off and plummeted down passing within 30 yards of Doc and Herb. Two arrows streaked toward the quacker, but passed several feet behind him.

Moments later a single surprised Steve and me and we both shot behind him.

"We're going to have to lead them more," Doc shouted as we scanned the sky during the momentary lull. "That's for sure," I answered. "I was ten feet behind that one."

Then Herb spotted a flight to the east and the big flock circled cautiously overhead several times before lowering the flaps. We waited until they were hovering twenty yards above the decoys and then let fly. All of us registered near misses.

"Those four arrows are lost," said Herb as he pulled another shaft from his quiver. This was the second of our major problems. The Platte has four separate channels at this point. We were hunting on the southernmost stream, which was thirty yards wide but shallow enough to wade. Only a narrow island separated this stream from the deep, main channel. Any arrows passing over the main channel were lost.

By midmorning we had all recorded several more near misses and the ducks were becoming increasingly wary.

"They must be spotting us," Steve said. "We'd better see if we can get under cover a little more." We all squirmed back into the brush and while the ducks did decoy better, we found it was more difficult to get off a quick, accurate shot.

About noon the action slacked off, and we gathered for a cup of coffee. I took advantage of the NEBRASKAland

'We've got thiee types of fletching and I don't know how many kinds of points," Herb said, noticing my interest.

Some of the arrows had flu-flu type fletching which limited their flight to about a hundred yards. Others had conventional feather fletchings, while the remainder had plastic-foam fletchings designed for use in wet weather. The tips were two-edge, three-edge, and razor-insert broadheads. A few carried special fish-hook tips which Herb had designed. This wicked-looking point has a two-inch-wide striking surface which allows a little more margin for error.

Herb shoots a 48-pound-pull bow while Doc was equipped with a slightly heavier 58-pound bow. Both Doc and Herb do some target shooting and their bows were fitted with sights. However, as they had expected, the sights were useless on the fast-moving ducks.

As I was examining the equipment several hundred mallards filled the sky and raised our hopes. "This is it," Doc whispered to me as we waited in anticipation.

Everything looked perfect, but, at the last minute, the ducks veered and dropped into the deep channel, just out of range. The beautiful sight of hundreds of mallards settling in just yards away, counteracted our disappointment.

"Now I know why the Indians were always hungry," Doc joked as we drove back to town that evening.

"I sure wish I'd had my shotgun," I said. "All those mallards and me with a bow and arrow."

"There wouldn't have been any challenge with a shotgun," Herb said. "We all could have filled out in an hour."

"This makes you appreciate the margin of error you have with a shotgun," Steve said. "With the 28 scattergun you have a thirty-inch pattern and a six-foot shot stream."

'We got a lot of good practice today," Herb said. "I think we have a good chance of scoring tomorrow." The next morning dawned clear and still. It was fifteen minutes after shooting time before we got any action. The four drakes came in and swung around when they spotted the blocks. When the ducks were within 25 yards, we let fly.

"I ticked a wing," Herb shouted as the drakes towered and continued downstream.

In the next hour the ducks were flying high in the clear sky and all our shots were tough ones. So, a lone greenhead caught us napping, when he landed in the decoys twenty yards from Herb.

"I wonder why Herb didn't take him coming in?" I asked Doc as the drake swam nervously through the decoys.

Then the duck rocketed skyward. Two wingbeats later the big duck and Herb's arrow met. "I hit it! I hit it!" Herb shouted as the duck fell back to the water with a broken wing. A mad dash followed as Herb ran down his trophy.

"I just clipped his wing," Herb announced as he returned to the blind, grinning like a schoolboy. "Why didn't you take him when he was coming in?" Doc asked.

"I was going to, but there was a bush right in the way," Herb explained. "After he landed I edged around to where I had a clear shot. I shot above him because he was just coining off when I released."

We only had a few hours left to hunt before starting the trip back to Lincoln, so we hunkered down in the cover again. Few ducks were flying and the occasional shots we did get were tough. It was almost noon and we were preparing to leave when a single plummeted from the sky, seemingly intent on landing in Doc's lap. The duck was six feet from the water with its landing gear down when the arrow passed directly beneath it.

"That one must have been too close for me," Doc said with a grin as we collected our equipment and headed for the car.

"Next time we'll have to bring portable blinds," Herb said as we started the long drive back to Lincoln.

"And we'll find a spot where we can retrieve our arrows," Doc added. T think we all would have taken more shots if we hadn't been worried about losing arrows."

"We lost about three dozen," Steve said, "and at $7 a dozen that means we got a $21 duck." "That's not bad," Herb said. "If you break it down that means we each lost about $2.50 worth of arrows each day. A lot of shotgunners go through that much."

"Like the guys in that blind downstream from us," I said. "They must have burned up a box of shells both mornings, and they only hunted for a few hours."

"They probably got their limits both mornings," Doc said, "but I'll bet they didn't have the fun we did."

"They weren't even around to see that huge flight yesterday noon," Steve added. "That alone was worth the money in my book."

The more I thought about it the more sense it made. With shorter seasons, smaller bag limits, and more hunters each year, we are going to have to find new approaches to hunting. While archery-duck shooting is definitely not for the meat hunter, it does offer the real sportsman a worthy challenge. THE END

NEBRASKAland

RETURN OF THE TRUMPETER

At the turn of the century, the great birds were gone from Nebraska. Today they are making a comeback

TRUMPETER SWANS, their white wings shining in the sun, once sailed like clipper ships across the blue Nebraska sky. Migrants through the state in April and October, they were seen along the Platte River from North Platte to Omaha. Some of the huge birds also made their home in the state, particularly in the Sand Hills. But, the trumpeters declined here as they had throughout their range.

In the early 1900's, it was noted in ornithological journals that the trumpeter swan was "rare in Nebraska" and that they "formerly bred" in Cherry County.

By 1912, the swan's numbers were so reduced everywhere that one authority made this statement: "The trumpeter has succumbed to incessant persecution in all parts of its range, and its total extinction is now only a matter of years."

Fortunately, this prediction proved inaccurate. In the record of modern man's efforts in wildlife conservation, the salvation of the trumpeter swan stands as one of the few victories. Man, responsible in the first place for nearly extirpating the trumpeter swan, must also be given credit for bringing this magnificent bird back from the edge of eternal extinction.

That the trumpeter could ever approach annihilation was surely an unbelievable notion to our nation's pioneers and frontiersmen. Vast numbers once ranged throughout the north, west, and central parts of North America. The big birds had breeding areas from Alaska and northern Canada south to Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Indiana. Autumn saw the great flocks move south and east as far as the Atlantic coast and the Gulf of Mexico.

But despite their original numbers, the trumpeters had to yield to the relentless pressure of the gun and the plow. Early settlers varied their steady diet of 30 deer and bison with young trumpeter swans. Market hunters included it in the list of birds they shot for a living, as the down and quills were valuable items of trade. Between 1823 and 1880, the Hudson's Bay Company sold some 108,000 swan skins, many of which are believed to have been those of trumpeters. Since the swan is ordinarily a low-flying bird, it was an easy and irresistible target for indiscriminate gunners.

Yet, the biggest reason for the dwindling of the trumpeter swan population was the loss of suitable areas for breeding. With the settlement and development of the Great Plains and far west, the swans no longer had the isolation they needed. Year by year, there were fewer lakes, marshes, and sloughs to which these great white birds could retreat for nesting and rearing of young.

Reduced by the 1930's to fewer than 100 birds in the 48 states, the trumpeters were making a last stand in and near Yellowstone National Park. Also, a few remnant flocks survived in Alaska and western Canada. The turning point in the near demise of this noble species was the establishment in 1935 of the Red Rock NEBRASKAland

Working to establish the Red Rock Lakes Refuge was a young project supervisor in the Refuge Division of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a branch of the Department of the Interior. This man was M. O. Steen, now director of Nebraska's Game and Parks Commission. Thirty-five years later, he sat behind his massive desk in the State Capitol and remembered the joy of seeing and hearing these magnificent creatures who rule the sky.

"Have you ever seen a trumpeter? They are the largest bird, by weight, in all of North America. Adults reach 30 pounds and have a wingspread of over 6 feet. On the water and in flight, they are truly beautiful birds. The name of the trumpeter swan comes from its call, a resonant trumpeting note. It sounds like the MARCH 1970 clear, ringing tones of a French horn and can be heard two miles away."

Because of Steen's great love for this exceptional species, all Nebraskans may one day be able to experience the sight and sound of trumpeters. The Game and Parks Commission has embarked on a program to bring trumpeters back to the state.

"We have both a moral and legal obligation to reestablish this truly majestic bird," Steen notes. "Trumpeters were a part of Nebraska's original fauna and should be restored if possible. It is also important that its numbers be dispersed throughout the original range. A catastrophe could wipe out the birds in one area."

Within the last 10 years, trumpeters have begun to return to Nebraska, but in a roundabout way. Surplus birds at Red Rock Lakes Refuge in Montana were sent to other areas as breeding stock for new populations. Some of these went to Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge in southwestern South Dakota. But at Lacreek there is not enough nesting area for the 70 or so birds that now winter there. In spring, the push to find breeding areas has (Continued on page 54)

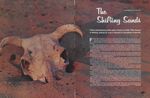

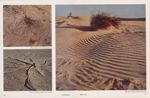

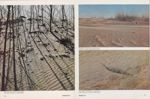

The Shifting Sands

These infinitesimal grains add a charm to state. Their beauty is fleeting, lasting for only a moment in hourglass of eternity

FROM TINY SPECKS of sand a hill grew. From that hill a man surveys the vastness of Nebraska's cattle country, In that vastness he finds beauty and because of that beauty he savors a moment of solitude. In solitude he discovers peace and with peace a world can be saved. All of this because of an infinitesimal grain of sand.

The mile-wide Platte River, a beach at Merritt Reservoir, the mighty Missouri, the endless Sand Hills, all hold a mundane sort of beauty, one so commonplace that it is seldom appreciated. There, wind and water paint temporary masterpieces on a canvas of sand Hut, in this subtle and leisurely art, there is reasoning. If man is to truly appreciate large, sweeping panoramas, he must first learn to discover nature's small, hidden treasures.

Rolling hilts, feeling the Midas touch of a rising sun, are easily recognizable for what they are, but few own eyes discerning enough to spy a sun-bleached bull skull, partially covered by the timeless sand. Such an eye will find a world of unusual beauty in the shifting sands of NEBRASKAland.

Whether it is in a hunter's boot or on a beach, sand adds a certain charm to this "where the West begins" state. In fact, the Nehraskans went so tar as to name their famed and vast cattle country the "Hand Hilts". Here, winds sweep the grass-covered hills, whisking out depressions known as blowouts. These nature-carved nests of sand are as common as cattle, but to most ranchers they are not quite as pretty. But even to a cattleman, the wind's etchings create a sense of western romance.

As the sands shift, they uncover whispers of the past. In a blowout a careful Searcher may spot an arrowhead or more recent evidence of man's presence a shotgun shell or a broken bottle. In a sense, these blowouts are hourglasses that measure mans progress on the plains.

In the hills "the sands of time" are quick io claim the neglected. An old fence line rumbles to the whims of wind and water. Then the same elements breathe a resolute anthem, as shifting sands slowly bury the wooden border guards of the prairie. An old wagon wheel meets the same fate, but in doing so it adds a cowboy grandeur to the lulls.

Sand marks time in other ways, too. Whether a man walks on a Missouri River island, along a beach of one of Nebraska's reservoirs, or through a draw, he leaves an impression in the sandy land that is uniquely his. The mobile sands honor his presence, but respect another man's search for solitude by slowly tilling the footprints left in passing. Therefore, it is up to the man, not nature, to preserve each step he takes toward tomorrow.

Like leaves in tall, patterns in the sand change with each drop of rain and sigh of the wind. Once man can appreciate these small, seemingly insignificant beauties, then he is ready to accept the challenge of more sweeping vistas, THE END

After 1924 Notre Dame epic, Knute Rockne ran into Nebraska dressing room and shouted...

"I WANT ED WEIR"

IN THE SHADOWS of Notre Dame's Cartier Field, the Four Horsemen rode again in a style that won them gridiron fame. In the fourth quarter the score was 34-6. You would have thought the points were in Nebraska's favor instead of the other way around, if you were watching a Nebraska tackle with a No. 1 on his back. That tackle was Ed Weir, and he smashed through the line to drop Jim Crowley, one of Notre Dame's cyclone backs, for a two-yard loss.

Knute Rockne, Notre Dame's coach, had watched Ed anchor down his position the year before when the 1923 Cornhusker squad had beaten his team. In the first half of this game, Rockne sent his backs galloping toward "the Superior, Nebraska, farm boy" in an apparent effort to beat Nebraska's best lineman. But Ed relentlessly reined in the Horsemen. By the second half most of the plays were going to the right, but even then the 6-foot, 191-pound player was in on "8 out of 10 tackles".

When the game was over, Ed Weir had tackled Notre Dame backs for a total loss of 13 yards, had been in on virtually every defensive play, and had played his finest game as a Cornhusker. But Nebraska had lost and the dressing room was quiet.

"I want Ed Weir," Knute Rockne shouted as he busted into the hushed Nebraska dressing room. Husker Line Coach Henry Schulte managed to MARCH 1970 mutter, "What's wrong, Knute? What has Ed Weir done? Why do...."

Rockne interrupted, "I said, I wanted Weir. Where is he?"

Schulte shrugged toward the corner of the dressing room, then quickly followed the Notre Dame coach.

Rockne grabbed Ed's arm and said, "Weir, I want to say to your face that you're the greatest tackle and the cleanest player I have ever watched. It takes a real football player to shine on a team that is being beaten, and you outdid everyone on the field today."

What Rockne said and did during the 1920's made sports headlines across the country. When the famed coach wrote in his weekly newspaper column that the real hero of the Nebraska vs. Notre Dame conflict was a player on the beaten team, Ed Weir was suddenly being compared to such 1924 greats as Harold "Red" Grange of Illinois and Rockne's own Four Horsemen. Eastern football writers, who couldn't see as far as the Mississippi River when it came to their AllAmerican picks, were unanimously naming the Missouri Valley Conference tackle to their teams.

But Ed's reputation as "one of the fastest and best

linemen" in the country wasn't built on one Notre

Dame game in 1924. The early 1920's was an era of

great players, teams, and coaches, and Ed led the Cornhuskers against some of the best. The 1920's also

43

meant one-platoon football and to make All-American,

a player had to stand out on both offense and defense.

Ed was best known for his defensive play, but he punted, kicked off, on occasion tried field goals and extra

points, carried the ball on tackle-around plays, went

out for passes, and opened gaping holes in the opposing

team's defensive line.

meant one-platoon football and to make All-American,

a player had to stand out on both offense and defense.

Ed was best known for his defensive play, but he punted, kicked off, on occasion tried field goals and extra

points, carried the ball on tackle-around plays, went

out for passes, and opened gaping holes in the opposing

team's defensive line.

In 1924, Walter Camp, father of football's All-American teams, picked Nebraska's junior tackle for his first string, and other football writers around the country followed suit. On the same team with Ed were three of the Four Horsemen and Red Grange. In 1925, Grantland Rice, who took over the All-American selections after Camp's death, picked Ed to his first team. In the same year, the Associated Press polled 100 writers and coaches and the Superior football star was a unanimous pick, something that even Grange couldn't accomplish in the same poll.

Ed was Nebraska's first two-time All-American and only one Cornhusker has done it since — Wayne Meylan, a 1966 and '67 middle-guard selection. In Ed's 1923 sophomore football picture, he was sitting in the third row from the back, but in 1924 and '25 he moved to front row, center as Nebraska's only two-time captain. In 1951, the tackle joined football's elite when he was named to the National College Football Hall of Fame.

Whenever great Husker teams and players are discussed, it is only natural to talk about Weir. Ed, who lives in Lincoln, is a Cornhusker football legend and except for a limp, the 66-year-old man looks fit enough to play in the Nebraska line even today. One evening in January, I stopped by his apartment to talk about his exploits as an All-American, a track star, and a head track coach at the University of Nebraska. For three hours I sat enthralled, as his deep voice and well-chosen words took me back to the days of one-platoon football and the triple pass behind the line. As Ed talked, I could see the square-jawed man in a set position, his deep-set eyes pensively studying the opposing line. With the snap of the ball, I saw him chase Red Grange out of bounds, then words later crash into the Notre Dame line to spill one of the Four Horsemen.

"The 1924 Notre Dame game was my best, even though we lost," Ed recalled. "It is hard to go back 46 years and recall certain plays I was in on. About the only thing I really remember about that game is seeing the Notre Dame No. 5 upside down when Elmer Layden busted through the line. I had quite a few tackles, but back then they didn't keep records on the number of tackles and assists a player made.

"To remember those football days, I keep this," the quiet man said as he opened a suede-covered scrapbook. The headline, "Nebraska 14, Illinois 0-Grange Stopped by Bearg's Men, Led by Weir", jumped out at me.

"We faced some tough teams during my three years as a player. Nebraska went against Illinois and Grange three times and Rockne's Notre Dame teams three times, twice when he had the Four Horsemen," Ed reminisced. "Our three greatest wins were the two against Notre Dame and the one over Illinois in 1925."

In 1925, Nebraska's schedule started tough with Illinois and ended up the same with Notre Dame. When Nebraska traveled by train to Urbana, Illinois, most fans expected to see the "Galloping Ghost" go twisting down the field as he had the season before. But this is how Grantland Rice, the dean of sports writers, described the game:

"Thousands turned out to see Red Grange. But in the Nebraska line was another gentleman, known in