NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

February 1970 50 cents EIGHT MORE COLORFUL PAGES EACH MONTH SYMPHONY OF THE SEASON INTRODUCE YOUR FAMILY TO A TENT SNOW TIME FOR RAINBOWS HOCKEY BEHIND THE SCENES

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland of the Air

SUNDAY KHAS Hastings (1230) 6:45 a.m. KMMJ Grand Island (750) 7:00 a.m. KBRL McCook (1300) 8:15 a.m. KRFS Superior (1600) 9:45 a.m. KXXX Colby, Kan. (790) 10:15 a.m. KRGI Grand Island (1430) 10:33 a.m. KODY North Platte (1240) 10:45 a.m. KCOW Alliance (1400) 12:15 p.m. KICX McCook (1000) 12:40 p.m. KRNY Kearney (1460) 12:45 p.m. KFOR Lincoln (1240) 12:45 p.m. KLMS Lincoln (1480) 1:00 p.m. KCNI Broken Bow (1280) 1:15 p.m. KAMI Cozad (1580) 2:45 p.m. KAWL York (1370) 3:30 p.m. KUVR Holdrege (1380) 4:45 p.m. KGFW Kearney (1340) 5:45 p.m. KMA Shenandoah, la. (960) 7:15 p.m. KNEB Scottsbluff (960) 9:00 p.m. MONDAY KSID Sidney (1340) 6:15 p.m. FRIDAY KTCH Wayne (1590) 3:45 p.m. KVSH Valentine (940) 5:10 p.m. KHUB Fremont (1340) 5:15 p.m. WJAG Norfolk (780) . 5:30 p.m. KBRB Ainsworth (1400) 6:00 p.m. SATURDAY KTTT Columbus (1510) 6:05 a.m. KICS Hastinqs (1550) 6:15 a.m. KERY Scottsbluff (690) 7:45 a.m. KJSK Columbus (900) 10:45 a.m. KCSR Chadron (610) 11:45 a.m. KGMT Fairbury (1310) 12:45 p.m. KBRX O'Neill (1350) 4:30 p.m. KNCY Nebraska City (1600) 5:00 p.m. KOLT Scottsbluff (1320) 5:40 p.m. KMNS Sioux City, la. (620) 6:10 p.m. KRVN Lexington (1010) 6:45 p.m. WOW Omaha (590) 7:10 p.m. KJSK-FM Columbus (101.1) 9:45 p.m. DIVISION CHIEFS WiHard R. Barbee, assistant director C. Phillip Aqee. research William J. Bailey Jr., federal aid Glen R. Foster, fisheries Carl E. Gettmann, enforcement Jack Hanna, budget and fiscal Dick H. Schaffer, information and tourism Richard J. Spady, land management Lloyd Steen, personnel Jack D. Strain, parks Lyle Tanderup, engineering Lloyd P. Vance, game CONSERVATION OFFICERS Ainsworth—Max Showalter, 387-1960 Albion—Robert Kelly, 395-2538 Alliance—Marvin Bussinger, 762-5517 Alliance—Richard Furley, 762-2024 Alma—William F. Bonsall, 928-2313 Arapahoe—Don Schaepler, 962-7818 Auburn—James Newcome, 274-3644 Bassett—Leonard Spoerinq, 684-3645 Bassett—Bruce Wiebe. 684-3511 Benkefman— H. Lee Bowers. 423-2893 Bridaeport—Joe Ulrich. 100 Broken Bow—Gene Jeffries, 872-5953 Columbus— Lvman Wilkinson. 564-4375 Crawford—Cecil Avev, 665-2517 Creighfon—Gary R. Ralston, 425 Crofton—John Schuckman, 388-442! David City—Lester H. Johnson. 367-4037 Fairbury—Larry Bauman, 729-3734 Fremont—Andy Nielsen 721-2482 Gering—Jim McCole, 436-2686 Grand Island—Fred Salak, 384-0582 Hostinos—Norbert KampsnMer. 462-8953 Hebron—Parker Erickson, 768-6905 Lexington—Robert D. Patrick, 324-2138 Lincoln—Lerov Orvls, 488-1663 Lincoln—William O. Anderson, 432-9013 Milford—Dale Bruha, 761-453! Millard—Dick Wilson, 334-1234 Norfolk—Marion Shafer, 371-2031 Norfolk—Robert Downinq, 371-2675 North Platte—Samuel Grasmick, 532-9546 North Platte—Roaer A. Guenther, 532-2220 Omaha—Dwlqht Allbery, 553-1044 O'Neill—Kenneth L. Adkisson, 336-3000 Ord—Gerald Woodgate, 728-5060 Oshkosh—Donald D. Hunt, 772-3697 Plattsmouth—Larry D. Elston. 296-3562 Ponca—Richard D. Turpin, 755-2612 Riverdale—Bill Earnest, 893-2571 Rushville—Marvin T. Kampbell, 327-2995 Sidney—Raymond Frandsen, 254-4438 Staoleton—John D. Henderson, 636-2430 Syracuse—Mick Gray, 269-3351 Tekamah—Richard Elston, 374-1698 Valentine—Elvin Zimmerman. 376-3674 York—Gail Woodside, 362-4120 3

WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to.- Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live National Wildlife Week March 16-22 Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAMFor the Record ... FALLACY OF FEEDING

SOME NEBRASKA WINTERS can be harsh and uncompromising, with blinding, wind-driven snow and freezing temperatures sweeping in to cause a bleak outlook for wildlife. At such times man ponders how any creature out in the open can possibly survive. Pheasants and quail are the most common objects of concern, for it is these highly-prized game birds which appear in need of man's help. The apparent simple solution seems to be put out feed to keep the birds from starving, but is this the answer?

Winter feeding may be likened to a doctor treating the symptoms rather than the disease. The patient may feel some better while being treated, but he will not get well until the disease has been properly diagnosed and treated. In the case of pheasants and quail it is the habitat which is deficient, and this cannot be cured by employing emergency feeding.

Farmers often feed a covey of quail or a flock of pheasants around their farmstead, and these individuals are to be commended for their concern. However, such operations are not to be confused with a mass-feeding program which is aimed at providing food for a large segment of the game-bird population.

There are a number of reasons why extensive winter-feeding programs are impractical, but the following are among the more important:

Costs for carrying out a feeding program are notoriously high. Grain is expensive, but even if surplus supplies are made available for winter feeding, the cost of distribution into the cover areas puts the program out of the price range. Grain scattered along the roads may result in increased highway kills. Besides, the roadway may be quite some distance from protective cover and birds use up needed energy getting to and from the feed. Putting out feed will concentrate the birds and may make them more vulnerable to predation.

Another drawback to winter feeding is that any grain that has been put out is drifted over and lost by subsequent storms. The winter of 1959-60 proved that dropping grain from an airplane is not practical because of cost and wastage.

Bobwhite quail and ring-necked pheasants have been here for a long time, and both species have gone through the conditioning process offered by Nebraska's fickle weather gods. Pheasants, and to a lesser degree quail, can survive most of our winters with only light or moderate losses. But during winters of unusual severity when repeated blizzards occur, losses are inevitable. By far the most common pheasant mortality is suffocation resulting from ice and snow forming over the bird's beak and nostrils.

It may sound like a fatalistic attitude, but when a genuine severe winter occurs we must expect heavy mortality, especially for quail. Although these losses can affect the number of birds available to the hunter, they can be absorbed by the population, and given favorable conditions in the years following, the birds will rebuild rapidly.

When severe storms strike, man would do better to ponder the improvement of habitat rather than lamenting the lack of feeding programs.

Las Vegas is all show.

See some Stars next weekend. Take off on a Frontier Fast Fling. Just like that. No counting off days. No waiting for vacation. It's a spontaneous thing, like any real good time. You can see more nationally known talent in one weekend than you'll see on television in a month. And, there's nothing like a live performance. Bring the family (there are family-type shows in Vegas). And Frontier's Family Plan is available every day on every flight. Next time you want to go out on the town, go to the town where you can go all out. Call your Travel Agent or Frontier about a Fast Fling to Las Vegas. FRONTIER AIRLINES a better way to fly NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970 5

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

SAVED AND SAVORED-"Of the several magazines that arrive at our house, NEBRASKAland is one that is saved and savored during the ensuing months. The pictures are of the highest quality. How about some of your excellent photography for Fontenelle Forest?"-Lew Clark, Sacramento, California.

SIX-MAN FOOTBALL-"I would like to see an article on six-man football. I believe this game was developed in Nebraska. It was played by small schools that didn't have a large enough enrollment to field an 11-man team.

"I saw one very fine example of this game when I was at Lincoln High. We 'scrubs' scrimmaged Cathedral High's six-man team. They had some very fine players. One was Bob Costello who went on to the university and turned in a stellar job. This game developed players of speed, quick reactions, and brains—not a bad combination." —John T. Anderson, Oakland, California.

LOSE MY TURN?-"Enjoyed the article on the Negro homesteaders in the February NEBRASKAland. Two of them carried our mail at different times when we lived in the Sand Hills. They used a team of horses and a squaw wagon and delivered twice a week. They came into Seneca from Brownlee on Monday and returned on Tuesday, then again on Friday and Saturday. In the winter, they would walk beside the wagon for miles to keep from freezing. One was named 'Serell', and if memory serves me correctly the other was 'Crawford'.

"In the 1920's, Mack Boyd and Turner Price played for a lot of dances in the Brownlee area and it was worth a long horseback ride to me just to watch and hear them entertain.

"I recall being in Mr. Hannah's barbershop in Brownlee waiting my turn when a cowhand with a few shots of 'Canyon Run' under his belt plus a heavy beard was in the chair. The barber's razor usually needed a little more stropping, so as the barber pulled the razor over the cowhand's chin, he asked: " 'Barber, if you drag me out of this chair with that razor, do I lose my turn?' "Mr. Hannah chuckled and whet his razor." —Mr. and Mrs. C. B. Huddle, La Crescenta, California.

BUCK FEVER-"I have bow hunted deer since I was 16 and in the ensuing 6 years, I have never filled a permit, yet the memories of the hunts have more than repaid me for the cost of the licenses. For example, I like to remember this hunt with a buddy named Pat who is now serving in the Navy.

"It was a cool November morning and Pat and I were in our tree stands before sunrise. It was foggy and we couldn't see more than a hundred yards, but we hoped the fog would burn off with the sun. Shortly after sunrise, I spotted two bucks heading for an alfalfa field. The fog was still pretty heavy, so I decided to stalk them and managed to get within 30 yards of the animals.

"I took dead aim and released. The twang of the bowstring alerted one of the bucks and he stopped short. The arrow passed in front of him. Then he and the other one ambled toward the field and were gone. Pat joined me just as I found the arrow.

"The fog diminished about 9 a.m., so we sat down to discuss our next moves. To our amazement, 22 whitetails came out of the brush and started grazing in the field. We were sure we would fill our permits in short order, so we headed down a draw to intercept the deer when they returned to the brush.

"Before long, the animals started back, one and two at a time. We picked our bucks and waited. Several small deer passed within 10 yards of me, and I was so excited, my heart was pounding like a bass drum. Suddenly, there he was, a five-pointer and headed directly toward me. I froze with my half-drawn bow, not daring to bat an eye. In seconds, the big buck was within 15 feet of me and completely unaware of py presence. Then I got buck fever. I couldn't bring my bow to full draw; I couldn't do a thing. Helplessly, I watched as the buck walked into the brush. Right about then I was ready to give up hunting forever.

"In the meantime, Pat bagged himself a fine four-pointer. He will never let me forget the day I had buck fever and let the most beautiful five-point buck I ever saw get away."—Sp/4 Dennis O. Meyer, Co. D, 4th Medical Battalion, 4th Infantry Division, APO S.F. 96262.

APOLOGY —"You owe Oshkosh an apology. In the October list of Nebraska airports you put 'none' under names, under runway surface, you put 'turf, under meals, 'none', under transportation, 'none', and under remarks, a blank for the Oshkosh airport. Our airport has a name, Oshkosh Municipal. It has a concrete runway 3,700 feet long and 50-feet wide. It is the only lighted and paved airport runway between Scottsbluff and North Platte.

"It is located adjoining the city. A cafe adjoins the airport near the administration building. Across the street is another cafe and two motels. Transportation? The administration building is four blocks from the main business intersection in downtown Oshkosh.

"Under remarks, you could put that this is the closest paved and lighted airfield to Lake McConaughy; you could mention the North Platte River and the sandpits one mile south, or the scenic Oshkosh canyons three miles south.

"You could mention the state game reserve along the river all the way through the county, making this a goose-hunting area, you could cite the antelope and deer that abound in the area, you could mention the pheasant hunting, you could mention Ash Hollow State Historical Park at Lewellen just 11 miles east, you could mention the brick clubhouse and the golf course a mile south, and you could mention the free swimming pool (heated) during the summer."-Charles E. Greenlee, editor Garden County News, Oshkosh.

Information in the chart was taken from the "Nebraska Airport Directory' published by the State Department of Aeronautics. — Editor.

INJUSTICE-"The article on the Borman Collection of Andrew Standing Bear's work in the December 1969 issue was a fine one, but because you do such fine color work I feel there was some injustice done to the paintings. Why couldn't we have some color pictures?" - Mrs. Marvin Morgan, Gordon.

The Where to Go department in NEBRASKAland is not set up for color reproductions. Sometime in the future, we may devote a" spread" to Standing Bear's art. — Editor.

RIVER VICTIM-"NEBRASKAland readers might be interested in this bit of history about Ionia, a one-time thriving town in Dixon County that is remembered for its 'volcano'.

"In 1856, three men surveyed and staked out the townsite of Ionia where three families were living. One year NEBRASKAland later, L. T. Hill, a merchant from Davenport, Iowa, engaged J. J. Pierce and his son to locate a townsite for him. Learning that the proprietors of Ionia desired to sell out, they purchased it for Hill who immediately started to develop it. At first progress was slow, and the village remained little more than a trading post and fueling station for riverboats. In 1860, Hill built the first ferryboat at Ionia. It was a great help to the farmers of Dixon and Dakota counties, who had to cross the river to sell their produce to the army at Fort Randall.

"The fifth post office to be established in Dixon County was located in the picturesque and historic village of Ionia. John J. Pierce was the first postmaster. He received his appointment April 20, 1860. The post office was discontinued in 1900, and the mail service transferred to Newcastle, Nebraska.

"In 1862, the large amount of good timber on the Ionia bottoms induced Hill to erect a sawmill and in 1867, a gristmill was added. Fitzgerald and Lyons built a large store, and in 1868, Isaac Hughes built a hotel. In 1869, Levines and Rose built a large two-story general store. Many new shops and residences were added in 1870, and also in that year the Ellyson brothers, Wall and Allen, built and operated the first steam ferryboat above Sioux City there.

"Ionia continued to flourish for several years. It reached its peak about 1875. At that time it boasted several generalmerchandise stores, two hotels, two sawmills, a gristmill, shoe and boot factory, drug store, two ferryboats, blacksmith shop, carpenter shop, and several hundred people. Then the river changed its course and started to cut away the townsite. The erosion became so bad that it became necessary to move what was left of the town to higher ground. It struggled along for several years until it ceased to exist as a town altogether.

"So, the same mighty destructive force that destroyed the Ionia Volcano, was also instrumental in the destruction of the town of the same name." —W. W. Ellyson, North Platte.

HANGING GAME—"Can any of your readers or staff members give me some advice on 'hanging' game before eating? We need this advice."-Mrs. I. A. Trively, Clemson, South Carolina.

A study has determined that the following procedure would yield the best venison. Skin the deer and wash it with clear, cold water to remove dirt, leaves, blood, and hair. Hang the animal in a clean, dry place with a near constant temperature of 34 to 36° F. A walk-in cooler is best, but a tight garage, back porch, or outbuilding can be used if the weather is cool. The aging period will vary but one to two weeks are the most desirable. Aging gives the meat a better flavor and helps tenderize it. — Editor.

FEBRUARY 1970Your Dealer Has These!

DOLLARS TO DONUTSUNION LOAN & SAVINGS ASSOCIATION

NEBRASKAland's MONEYIand 209 SO. 13 • 56TH & O • LINCOLN 1716 SECOND AVE. • SCOTTSBLUFF

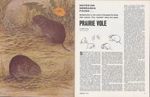

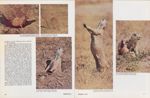

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . .

Multiplication is the name of the game for these little rodents. They "explode" every four years

PRAIRIE VOLE

SLEEPING BY DAY and working by night is normal procedure for many Nebraska mammals. From dusk to dawn the woods, hills, and grasslands are alive with thousands of tiny creatures, scurrying about searching for the necessities of life. Perhaps one of the busiest of these nocturnal prowlers is the prairie vole, or meadow mouse as he is often called.

Although not a familiar sight, this small, stocky, grayish to blackish brown rodent with light underparts and short tail is distributed throughout Nebraska, and in some areas rivals the western harvest mouse and the white-footed mouse as the most common mammal.

His scientific name, Microtus ochrogaster, which is about as long as the animal it describes, comes from four Greek words, "Mikros" -small, "ous"-ear, "ochro" -yellow, and "gaster" -belly. The vole belongs to the family Cricetidae which contains small to medium-size rodents.

The vole begins his 15 to 16-month life as a blind, deaf, naked 1/10-ounce ball of wrinkled skin. His childhood lasts until the ripe old age of two weeks after which he is on his FEBRUARY 1970 own. The species begins breeding at about 28 days and producing young at 49 days. One of the most prolific mammals known, the vole may produce many litters a year, the number depending on food supply, temperature, amount of cover, abundance of mates, and other factors. A litter may contain one to seven young, but three, four, and five are the most common.

An adult will usually weigh about 1 1/2-ounces and grow to lengths from 4 1/2 to 7 inches. His large head, long hair, short legs, and tail give him a sluggish, roly-poly appearance which can be quite deceptive to a predator with an easy catch in mind. The vole can run like lightning for 50 to 100 feet, and, if in trouble, can swim up to 900 feet. Speed is not his only defense, however, for he has razorsharp teeth and claws, a constitution of steel, and a fair amount of intelligence to help in his constant fight for survival.

Open season on the vole runs the year around as far as his enemies are concerned. Foxes, coyotes, skunks, weasels, raccoons, cats, and snakes will seldom pass up a meal comprised of the careless rodent. Airborne danger, in the form of owls, hawks, crows, and magpies is ever present in our small friend's world.

The vole's habitat includes herbaceous fields, grasslands, thickets, fallow fields, fencerows, alfalfa fields, bluegrass, clover, and lespedeza. A system of well-defined runways is built both on top and beneath the surface of the ground and it is in these passageways or tunnels that much of the vole's short life is spent. The passageways lead to feeding grounds which are usually shared by the entire community including the voles, other mice, shrews, and moles. Not a world traveler, the vole usually spends his busy lifetime within an area of one-half acre, and if he isn't being chased by a hungry intruder or mating, he usually can be found within 20 to 30 feet of his home.

Multiplication is the name of the game in the vole's fight for survival. A population explosion, usually occurring in four-year cycles, helps keep his numbers up while playing an important role in the balance of nature. During this explosion the vole can be very destructive. A theoretical population of 100 per acre will consume 300 pounds of alfalfa per year, or 96 tons per year per section, while wasting at least twice this amount. This large population will blight whole orchards in its quest for the inner bark of the trees. When food is scarce on the surface the vole will dig about seven inches into the ground to feed on roots. During the boom, man employs many tactics to reduce the onslaught, but disease and predation are the major factors which return the voles' numbers to a proper balance.

The beneficial role of the vole is often overlooked because of the adverse effects he has on crops during his times of abundance. His tunneling and other life activities help keep the soil well cultivated, which aids future plant growth. He provides an important link in the food chain by converting the nutrients from vegetation into his own flesh, and passing them on to the predators which feed on him. He reduces predation on other and more desirable animals such as game species by being a numerous and ready food supply, and to some extent, regulates the population trend of those who prey on him.

The prairie vole will probably never take the Animal of the Year Award or rank in the top 10 of "Who's Who Among Furry Creatures", but he will continue to play his small but important role in nature's delicate balance. THE END

9

THE GREAT HANG-UP!

MY LUCK TURNED COLD

CARRYING MY shotgun, in case a finishing shot was needed, I set out across the Lake McConaughy ice to retrieve a duck that had dropped some distance from our blind. I was only a few yards out when the ice began to crack all around me. There wasn't time to retrace my steps, so I threw myself forward with my shotgun under me just as the bottom fell out. My effort kept my head from going under, but the rest of me dropped into the icy depths. My breast waders filled up and several gallons of frigid water soaked into my many layers of heavy clothing. My two companions rushed to help me, aware that our routine hunt could turn into a tragedy.

We had arrived at the blind shortly after 5 a.m. that December day in 1965. Within minutes we had our limits of mallards. Rather than quit so soon, we voted to sit tight and see if some geese would start moving.

Perhaps an hour had passed when three ducks winged toward us. I don't remember what they were, but they weren't mallards so we tried them. Two dropped, one close to the blind and one well out. I volunteered to get the far one, not knowing until the ice gave way beneath me that the river had changed its course and undercut the ice just yards from the blind.

By kicking and crawling I finally worked out of the hole onto thicker ice. I dumped the water out of my waders and wrung out my socks right away, but the big problem was still ahead. It was 1 1/2 miles to the car and the temperature was well below freezing. Already, my outer clothing was glazed with ice, so I told my friends I would go to the car and sit in front of the heater until they were ready to head home.

Jumping up and down frequently to keep up my circulation, I made the first few hundred yards without any trouble. Gradually, however, my feet and hands lost their feeling. And, to make matters worse, I had a growing urge to rest. Soon, rest became the most important thing in the world to me, but I knew I had to keep moving. Memory of what had happened a few years before to an acquaintance goaded me on. He had frozen to death under very similar circumstances. He had stopped to rest during a storm, and he never got up. If I possibly could I wasn't going to let that happen to me. Still, there was a long way yet to go, and my mind started to wander.

Time meant nothing to me, for reality went no further than the next 10 NEBRASKAland

It looked like all my efforts were to be rewarded by an even more grotesque quirk of fate. Vainly I fumbled with all my might for the keys in my pocket, but the numbness in my fingers made my groping useless. Without the keys I couldn't get into the car. I was worse off than ever.

Gradually, the desire to keep struggling left me, and I felt the first pangs of fear creep through my bitterness. I thought of lying down beside the car, out of the wind, and hoping that my friends got there before it was too late. I was completely miserable and dejected. It seemed like my last glimmer of hope was locked up in that frosty car, and I couldn't get at it.

Then, just at the darkest moment in my life, with severe frostbite or maybe worse only minutes away, a FEBRUARY 1970 bright spark came. Another friend, Bill Craig, drove up in a nice warm pickup. Just like that, the whole picture changed, this time in my favor. Bill needed only a glance to know I was in trouble. He pushed me into his truck, peeled off my icy outfit, and put some of his own clothing on me. Then he made me sit in front of the heater where the warm air could blow on my hands and feet.

The experience is long behind me, but every time I think of it I also think about my friend who wasn't so lucky. I know all too well how easy it is to give up. Fortunately things worked out for me, but what if Bill hadn't come along when he did? THE END

Go Adventuring!

Do you know of an exciting true outdoor tale that happened in Nebraska? Just jot down the incident and send it to: Editor, NEBRASKAland Magazine, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska 68509. For free brochure write: OLD WEST TRAIL NEBRASKAland State Capitol Lincoln, Nebr. 68509

Amazing 100-Year-Old Gypsy Bait Oil MAKES FISH BITE

OR NO COST!All Types LIVE BAIT

OPEN-24-HRS. MAY 1ST TO SEPT. 1ST South Side Co-op 8501 West "O" Street (Emerald) 435-1611 Lincoln, Nebr. 68502Finnysports

FREE CATALOG Wholesale prices on fishing tackle, guns and hunting equipment, archery, skis, and camping equipment. Finnysports 2970J Sports BIdg. Toledo, Ohio 43614CELEBRATE NEBRASKA'S BIRTHDAY!

MARCH 1

FISH ON A BOARD

From bragging-size fish to "proof positive" takes only kit and a few hours

AN OLD SAW admonishes that "You can't have your cake and eat it, too", but such is not the case with a fish. There is a way you can eat a big fish, yet retain it as proof that "Here is a big one that didn't get away".

After all, what good is it to relate the glowing details of a momentous battle with the monster of Miller's Pond, if your listeners don't believe a single word? An angler's reputation is not above reproach, so as proof of your veracity as well as your fishing prowess, you need the full-scale, bona-fide, unquestionable evidence hanging right there where your audience can see it.

Mounting a fish is the answer, and it is nothing new. Yet, most anglers would rather gain a reputation as an exaggerator than spend $25 or more to have a prize catch preserved. But, there are inexpensive and easy ways a beginner can mount his own fish and still have a professional-looking job. One way is to buy a commercial fish-mounting kit, which contains the preservative, stuffing material, two fish eyes, paints and varnishes, instructions, and tools, including scraper, needle and thread, skinning knife, and paper clips. An alternative is to round up these materials on your own from a taxidermy supply house. Initially, the fish-mounting kit is the easiest.

Following the directions supplied in the kit, Norm Stucky of Lincoln took an 11-pound northern pike and converted it into a praiseworthy wall decoration. To duplicate the pike's exact size later on, Norm measured the body at the tail, near each fin, and at the head. After selecting the best side, he made an incision along the entire length of the other side from base of tail to gill cover, then started skinning it.

When removing the skin, leave a little meat rather than risk cutting through. Any flesh on the skin can easily be removed afterward with the scraping tool included in the kit. As much meat as possible should be taken from inside the head and next to the fins. For best results, keep the fins wet by daubing with water. Any remaining meat should be liberally treated with preservative. This granular powder must be rubbed in well and pushed into all unscraped cavities.

With the fish properly preserved, the stuffing begins. First, form a pocket at the tail by stitching up about three inches, then push in the prepared stuffing. Sew another few inches and pack in more stuffing. At this point your earlier measurements become very important, as you want to bring your fish skin back out to

When all sewing and stuffing are completed, clean the fish with paint thinner or gasoline to remove grease and dirt. Next, form the fins into shape by flaring them, then hold that shape by placing cardboard on each side and paper clipping them together. Wait until the fins are completely dry, then put a coat of varnish on the backside of the fin. Next, lay on a single thickness of facial tissue and give it several coats of varnish. Eventually, the tissue will become as strong as the original fin.

After five or six days of drying, clean the fish once again and coat the entire surface with varnish. The false eye can be put in snugly by using putty or wood filler. When the varnish dries, painting can begin. Color photos of fish are helpful, and the job will vary in difficulty depending upon the species. Usually the fish fades during processing, so the original colors must be duplicated by using paints.

Norm's pike turned slate gray on the back and sides, while the spots became indistinct, palid marks. Dissatisfied with the paints in the kit, Norm mixed small quantities of artist's oil paints, diluting them with paint thinner rather than linseed oil, which requires a longer drying time. If the color was too dark or heavy, he spread it with his finger. The white belly was done first, and the paint was kept thin and somewhat transparent to prevent that "covered-up" look.

When the gray areas were returned to a healthy green tint, the spots were retouched with a very light yellowish-white, also softened with fingertips so they did not appear artificial. Touching up the fins must also be done carefully to avoid a plastic look, so go easy with the paint, diluting it with thinner and shading, rather than plastering it on.

When painted, let the fish dry, then give the whole works several more coats of varnish or use a clear plastic spray. This not only preserves the paint and the fish, but gives that "wet" look. For neatness, the throat should be closed off with plaster of Paris or putty.

If possible, run through the entire routine on a smaller, practice fish and your second effort will then be much improved. Still, careful work on your initial try can mean a surprisingly good job—one that will back up your angling story and brighten your den. THE END

13

MOOSE HUNTS DEER

Does 75 years of experience equal 5 minutes of female intuition? I find out on a Mues shoot

WHEN IT COMES to deer hunting, 5 minutes worth of womanly intuition is sometimes more effective than 75 years of experience. At least it was last deer season when Margie Mues decked a five-point whitetail while the menfolk of her family went deerless. Here is how it happened.

Back in June I heard of the Mues family and their deer-hunting prowess. The name Mues (pronounced moose) intrigued me, and I sensed the makings of a good story. So, it didn't take long to wrangle an invitation to join the three-generation family on a week-long try for whitetails along the Republican River in west-central Nebraska. The Mueses live near Bartley and have an enviable record on the white-tailed bucks.

Rudy is the patriarch of the clan. Tall and spare and as tough as a pine knot, he is on the shady side of

When the Saturday opener came in November 1969, I was there complete with .30/06 and two deer permits. Don gave me a quick rundown on their hunting techniques.

"We're great for tree stands and the wait-for-them bit. I've got a couple of good ones lined up for you and me on the south side of the river. Dad and Dennis have their favorite spots on the north side about a mile east of here," my host explained.

It was still 45 minutes from dawn as Don and I waded the shallow Republican and fought our way through the dog-hair-thick willows that fringed the channel. My guide was a good navigator but awfully fast and I puffed to keep up. Finally, the Bartley hunter stopped and clued me in.

"As soon as we break out of this scrub, we'll be in the bigger timber. Your stand is about 20 yards from here in that leaning cottonwood. I'll be about 400 yards west of you."

The break gave me a chance to shuck my waders in favor of a pair of light hiking boots that I had carried across the river.

"I'm not in shape for all day in heavy boots," I grunted as Don fidgeted at the delay. "Besides, I'm the

nervous type and about two hours are about all the

waiting I can take."

nervous type and about two hours are about all the

waiting I can take."

"We don't stay out all day. If we don't score by 10 o'clock, we go in, eat, rest a bit, and try again in the afternoon," Don reassured me.

He snicked a cartridge into the chamber of his .264 Magnum, threw me a good-luck wave, and before I knew it, he was gone.

The east was lighting up but it was still dark beneath the trees, so I inched my way toward the cottonwood and gingerly eased my way up its slanting trunk to the first "Y", determined to stick it out for a couple of hours.

My stand was a good one, with an unobstructed view to the east and south. Don's strategy was evident. Deer that had left the willows to feed in the adjacent croplands during the night would be sneaking back to laze out the day, so there was a better than even chance that an old buck would meet the business end of my rifle head-on.

The river came alive with the young morning. A ragged formation of crows cawed across the graying sky and awakened a fox squirrel into a scolding rebuke. Out in the water a pair of mallards splashed and quacked with commotion enough for a dozen ducks. A few small birds twittered and fluttered about my tree and finally overcame their timidity to perch in the smaller branches above.

"Let's see, Rudy and Don have hunted deer for about 25 years. That makes 50, and I've got about 25 seasons here, there, and everywhere. Dennis has been at it about 3 years, so that makes 75, 76, 78. Let's be conservative and call it 75 years of experience. Yes sir, we're going to get some deer," I mused.

Three hours later that confidence had ebbed considerably. There hadn't been any shooting within

Three does, one a great big one, passed right under me," he sighed. "You see anything?" I shook my head. "Not a hair."

On the way back I questioned Don about Margie. She had accompanied us for about 200 yards toward the river before slanting off to the east.

"Oh, she's got a favorite stand at the corner of that field. She's shot a few bucks from there, too, but hunting is a casual affair with her. She plays hunches and hunts when she feels like it," her husband explained.

Rudy and his grandson came in shortly afterward. Their luck was poor, too. Dennis had seen a small doe,

In a way, I was in the catbird seat. One of my two permits was an "any" deer ticket. Last year for the first time, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission inaugurated a system whereby permit numbers divisible by a certain digit entitled the holder to any deer. Luckily, I had drawn one on my second application.

We decided to follow the morning routine that afternoon, but the matinee was the same story for me until 10 minutes before quitting time. A sharp bark of a heavy rifle shattered the evening stillness, so, I surmised that Don had scored. He had quite a story when he finally rejoined me.

"A friend of mine dropped a small doe just below me. He dressed her out, but it got too late to tote her across the river before dark. I'm going after her in the morning with my four-wheel drive. I can work my way down pretty close to the water and save a lot of work for him," he announced.

"How about the coyotes, won't they chew her up?" I questioned.

"Nope, I put my jacket over her and the man scent will keep them away."

We hunted for a couple of hours the next morning before returning to the house to get the truck. Dennis and Rudy hadn't had any luck either, so the youngster decided to go with us while his granddad caught up on some farm chores. Lloyd, Don's other son, was too young for a license but wanted to go, too, so Don told him to pile in.

"Had I better take my rifle?" I asked.

Don grinned. "I never go into deer country without mine."

We were skirting a cornfield on our roundabout way to the river when one of the boys started pounding the cab.

"Deer! Deer!" Dennis shouted as Don braked the truck. The animal was at the outer edge of the corn, looking more curious than startled at our appearance.

"Must be a doe," Don remarked, studying the animal through his scope. "Take a look." My scope confirmed that it was a small mule deer without antlers.

"You've got a doe permit, better take her," Dennis urged.

I didn't particularly want her, but a deer in the sights is worth two in the future. I leveled the .30/06, centered the crosshairs, and squeezed the trigger. The deer made three frantic lunges and piled up. Lloyd was the first to reach my kill.

"Button buck," he yelped excitedly.

We dressed the buck out in a few minutes and tossed him in the truck. Although the animal was small, he did cheer us up. "Maybe he's the ice breaker," Don opined, "We can sure use one."

After retrieving the doe of the evening before, we returned to the house, hung the animals in a tree, and went back to hunting. None of us saw a thing.

The next morning we changed tactics. Don, who had permission to hunt several miles of river, took me about three miles to the east with instructions to hunt the north bank back while he paralleled me on the south. Rudy and Dennis stayed in the general area of their tree stands with plans to hunt west after they tired of waiting.

I spent most of the morning on stakeout watching a sandbar, and then started still hunting back with many a long wait between steps. Time passed quickly and before I knew it, it was (Continued on page 64)

16 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970 17

TO KEEP THEM ON ICE

In sport where stitches and scars measure a player, Rock Batley is both a mother and maid to 20 men

WHEN THE PHONE rang at 4 a.m., Rock Batley switched on the lights and fumbled for his glasses. As a trainer for the Omaha Knights, a Central Professional Hockey League team, he expected late-night calls. But he dreaded them just the same, because they usually meant trouble. Yawning, he picked up the receiver, listened, then mumbled instructions to the caller. Several minutes later the phone rang again.

"Rock, I tried the ice, but the nosebleed still won't stop," a worried voice on the other end indicated. "In fact, my nose has been bleeding since 12:30 a.m."

"I'll be right there," Rock muttered. In a tough Wednesday night game, Syl Apps had been bashed in the face. Rock had stopped the bleeding and the player finished the game. After the contest, the trainer checked the nose again and it appeared to be all right. But when Rock arrived at the apartment and saw the player's bloody bathroom, it was apparent that things weren't all right. The trainer took Syl to the emergency room at a hospital. The player had lost a lot of blood, but the injury was just a complicated nosebleed.

The 36-year-old trainer is No. 21 on a 20-member team. Fans see him at every game, but few recognize the 5-foot, 10-inch bachelor as an integral part of the team. When he sits in the back left corner of the players' box, he looks just like an ordinary fan who is watching, waiting, and hoping for another Omaha goal. But the man from Peterborough, Ontario, is more than a spectator. He is totally involved in a game that is considered the world's fastest sport.

"A trainer is the forgotten man on a hockey club," Larry Popein, coach of the Knights, said as he sat in his office at the Ak-Sar-Ben Coliseum. "His work is important, and a poor trainer can 18

Describing a trainer as the mother and maid of a rugged group of men doesn't quite fit the hockey-player image. But the young men, who turn the coldness of ice into a heated battleground of human conflict, are potentially worth $20,000 to $100,000 to the New York Rangers, the Knights' parent club. As a trainer, it is up to Rock to protect that investment. That means 8 to 15-hour days and plenty of behind-the-scenes work that few fans know or even care about. But Rock's work is just as much a part of hockey as shoving a puck past a goalie for a score.

A metal door marked "No Admittance" at the far end of the Omaha rink hides Rock's major contribution to the Knights' team effort. Behind that door and up a short flight of wooden steps is the Knights' dressing room. The distinctive "dressingroom" odor is there, but the tall, metal lockers associated with most sports aren't. In their places, long, wooden footlockers that serve as benches line three of the walls in the players' room. Behind the benches hang part of the 16 pounds of paraphernalia that a player wears when he skates out onto the ice. Below the footlockers are names of players written on tape, a hopeful sign that these young men have not come here to stay. But there is nothing permanent about this room except maybe a bulletin board on the wall opposite the stippled-glass windows, a scale, and a table in the middle of the room that is littered with pop cans, tape, broken skate laces, foam padding, and pieces of gauze.

For the last three years the Omaha dressing room has been Rock's world of hockey because this is where he does most of his work. To find out how important Rock's job is, you have to run, not walk, after the quiet, but always smiling man as he scurries around the dressing room. There isn't such a thing as a typical day in the life of a trainer, because his daily procedures will vary with the schedule of home and away games, the practices, and the number of injured players he has to take care of.

When the team is between games there are daily practices. From the time Rock unlocks the dressing room door at 9 a.m. until the last player hits the ice at 10, he is besieged by 20 players.

"Hey, Rock, do you have any gum?"

"Rock, the Frenchman won't believe me. I'm right, aren't I?"

The trainer didn't hear the question because he was too busy checking Andre Dupont's sprained thumb. But he nods his head in agreement anyway.

"My line is short one yellow practice jersey, Rock."

As the slightly-balding man throws a jersey to the player he quietly asks goalie Peter McDuffe, "How is the leg?"

"Sore!"

"Better let me rub it down now and we'll put some heat on it after practice," the trainer orders as he leads the player down a narrow hall that is lined with hockey sticks.

In a room that is barely large enough to hold a black rubdown couch, a medicine chest, a folding chair, and a table, Rock massages the goaltender's bruised leg. As (Continued on page 52)

19

Symphony OF THE SEASONS

A DAY IN spring is a melody of wild-rose blossoms peeking through prairie grass. Summer sings with an orchestra of crickets, streams, and trembling cottonwood leaves. Fall and winter, too, have their musical moments. In the following pages, NEBRASKAland photographer Lou Ell has tried to capture the seasons' symphony on film. Let these pictures help you interpret your own symphony of the seasons.

Nature's song is a combination of moods and tempos. Slow, ponderous clouds set the stage Adagio

20 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970 21

Allegro

Happiness is music for the soul, but frolic and life are fleeting, like the flight of a bird

Splashes of color strike the eye like the quick, sharp rhythm of many marching feet Staccato

24

An audience to the outdoor concert, trees send up thunderous applause to each colorful crescendo

Fortissimo

NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970

Pianissimo

Soft, muted color of floating leaves, a fawn, and man's image in the sunset are nature's repose

28 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970 29

SNOW TIME FOR RAINBOWS

Many anglers think of trouting as a warm-weather sport. But my partner and I find there are advantages to cold-weather outings

THE WINTER of 1968-69 was the worst one in northeastern Nebraska for a decade. Old-time ranchers and farmers in the O'Neill area where I live, claimed that for sheer tenacity it was as bad as any they could remember. The first snow fell in mid-December and just kept coming. It was so bad that huge drifts remained until after the first of April. My gripe' over being snowbound was petty, perhaps, in light of the loss of livestock and wildlife, but it was frustrating to plan a trout-fishing outing and then be deterred by consistently bad weather, and snow-blocked roads.

Many anglers think of trouting as a warm-weather sport, but my fishing partner, Stan Gutshall, an O'Neill optometrist, and I enjoy matching wits with rainbows and browns when it's cold. Cold-weather fishing has its advantages. The summer crowds are gone, and we aren't eaten up by flies and gnats while we fish. After I retired in 1963 from a meat-packing company in Omaha, I moved to O'Neill. Since leaving the work-a-day world, I have plenty of time for fishing, and mv favorite angling day is Wednesday. Stan takes a mid-week break from his practice then and we go fishing.

Now it was mid-March and our winter trips had been seriouslv curtailed because of poor roads. However, Stan called on a (Continued on page 53)

WHEN THE WIND IS RIGHT

Danny Liska is what most men want to be-true globe-trotting adventurer

DANNY LISKA IS what most men want to be - an adventurer. The native Nebraskan is the first, and probably the only man, to travel entirely overland from the most northern town in North America that can be reached by road, Arctic Circle City, Alaska, to the most southern town in South America, Ushuaia, Argentina. That easily qualifies him as a man among men, but the Niobrara rancher has also ridden his motorcycle from the northernmost cape of Norway to the southern tip of Africa.

Think of the most fantastic events that could happen to a man, and they have probably happened to Danny. Vampire bats have sucked his blood, he has eaten monkey and lizard to stay alive, traveled through a jungle with smugglers, suffered from malaria, doubled as a stunt man for Yul Brynner, and ridden a motorcycle over 200,000 miles. His two major trips took a total of 36 months, and since then he has visited South America several times.

Few men will ever equal Danny's amazing globetrotting feats, for the 40-year-old is one of the few true adventurers left in this world. To write about all of Danny's adventures and still stay within the confines of this magazine would be like trying to stuff a motorcycle, a sleeping bag, a knife, two cameras, a 30-day ration of food, and all of Danny's thousands of travel slides into a flight bag. The story of his journeys would easily fill a book, and Danny is currently doing just that. Because of this, I will dwell on Danny's first and probably his most difficult trip, from Alaska to Argentina.

Why does one man accomplish what thousands only dream of? Danny, who has the chest and arms of a mountain man, is basically a common man, with common hopes and common dreams. But, while most men dream of being "fancy free", he turns those dreams into reality. Danny wasn't always an adventurer, and like most young men his plans for visiting distant lands were shelved with his mementos of the senior prom. But the rancher still read and wondered about exotic lands. Finally that, combined with sunrise to sunset work, pushed him into taking a two-week motorcycle trip to the West coast in 1957. That trip changed his life.

"I stopped to see the sequoias in California, and as I sat in the midst of these oldest living things on earth, I began to wonder why I was here and what I was going to do while on this earth. The concept of time had always eluded me, because man can measure most things. He can measure an inch, a mile, a pound, and even a year, but how do you measure a lifetime? I suddenly realized that those very old trees would best qualify to measure a man's life. I found a downed sequoia that was 80 feet around and counted off 100 rings — as an insufferable optimist each ring represented a year in my life. I was already 27, so I subtracted that number from FEBRUARY 1970

In 1959 Danny stopped talking about adventure and started doing something about it. He made a seven-week trip to Alaska with the idea that it would once and for all satisfy his desire to do something different. Instead, it only whetted his appetite to accomplish that one goal he had often thought impractical—the Alaska-to-Argentina trip. For a weaker or less dedicated man, the Alaska jaunt would have more than satisfied the thrill for adventure. On the lonely stretches of the Alcan Highway he was constantly battered by rocks thrown by passing trucks, and from the very start he was caked in mud. But Danny was searching for one thing —the end of the road in Alaska. He found it at Arctic Circle City, and when he did, he headed for home.

Back in Niobrara, Danny found that his Alaskan

adventure gave him a lot to talk about, but he wasn't

interested in talking. When the grass turned green in

the spring of 1960, Danny looked across the rolling hills

of the Niobrara River valley and wondered if he could

make it to the tip of South America. There was only

one way to find out, so one day, "when the wind was

33

As Danny rode into Mexico he had doubts about the journey he had started. He had left Niobrara with little advance preparation, and he wondered if he should turn back. Danny had visited Mexico before, when he was 19, and on that trip he had made an unsuccessful attempt to climb the volcano Popocatepetl. As he neared the mountain on this, his second journey there, he decided that the mountain would be his test on whether or not he had the strength and endurance to continue the trek. If he made it to the top of Popocatepetl, he would head south. If he failed, he would return to Niobrara.

Danny couldn't find a guide to go with him, so he rode his machine up the mountain as far as he could. It was foggy when he clamped spikes on his boots, grabbed an ice pick, and started the climb. After what seemed like hours, he was so exhausted that he collapsed in the snow. His lungs felt like they were on fire and he was physically beat. But Danny found himself in a strange situation, one that most men never have to face. He had a choice of success or failure, and he was the only one who could make the decision. Slowly he got to his feet and started climbing.

"As I walked up the mountain a step at a time, I realized that there is only one way to get to the top, whether it be a mountain or another goal in life. A man should make just the next step his goal, not the entire mountain. When I made it to the top of Popocatepetl, I knew that I would finish my journey."

Danny's wife, Arlene, joined him in Mexico and the two of them headed for Panama. Heavy rains and unfinished roads made the going tough, and in Costa Rica it took 5 weeks to travel 120 miles. Arlene became ill, so in Panama City she climbed on a plane and headed back to Niobrara, leaving Danny to face the most difficult part of the trip alone.

The road south ended 37 miles out of Panama City, and beyond lay 450 miles of some of the most impenetrable jungle in the world. There were no roads, no trails — nothing but jungle, "wild" Indians, snakes, and vampire bats.

"When I came to a sign that read 'End of the road ... Here begins the Darien Gap", a Panamanian walked up and said, 'Mon, you're crazy to think about going into that jungle. No mon goes in there and comes back'.

"I have nothing but contempt for pessimists, and by now I didn't believe in anything but myself and Popocatepetl. Somewhere beyond that trackless wilderness was Turbo, Colombia and that magic line that would carry me, aboard my motorcycle, to the end of my rainbow —the tip of South America.

"Behind me lay a similar trail that I had come to know. From the barren wastes of the treeless tundra of Alaska we had come through tall forests and quivering muskeg. We had sloughed through Costa Rica in the rainy season when all other traffic was at a standstill. Rain, rain, and more rain, it came down in torrents for 14 days. Landslides and 38 bridgeless rivers to cross, rivers that were choked with debris. People told me I was crazy in Arctic Circle City, Alaska, at home in Niobrara, in Costa Rica, and now at the edge of the jungle in Panama. I didn't deny it, because you have to be a little insane to try a trip like this.

"I had to ship my bike to Medellin, Colombia, but I wanted to take part of my motorcycle with me through the jungle. Before loading the machine on a plane, I took the license plate off and tied it to the back of my pack. I put the keys in the pack, along with food for two days, a hammock, my camera, a machete, a hunting knife, canteen, maps, salt, a snake-bite kit, penicillin with syringe, an extra pair of socks, mosquito repellent, matches, and garlic. I always carry garlic because a witch doctor told me it repels snakes as well as people."

On December 5, 1960 Danny and a Spanish-speaking guide called Mathews headed into the Darien in a piragua, a craft hewn from a single tree trunk. The two men stopped at several Cuna Indian villages to inquire about a guide that could lead Danny overland through the Chucunaque Valley. His overland-guide problem was solved when a young Cuna, who Danny called Manuel, offered to take him through the valley. Although Manuel had never even seen the valley, he was confident that for three dollars a day, a lot of money to a Cuna, he could find the way.

"The trail grew steadily worse, and when it disappeared entirely we had to cut our way through a tangle of vines and ferns with machetes. Manuel assured me that we weren't lost, but as we crawled on our bellys through the jungle, it was hard for me to believe it. When we finally found a path, I never again doubted him."

After Danny and Manuel finally made it to a Hill Cuna village, he sent the guide out in search of eggs. Minutes later three chiefs informed the Nebraskan that he had broken a tribal rule by not first getting the chiefs' permission to buy food in the village. Immediately, they informed him of other tribal laws.

"They told me where and when I could relieve myself, because they use the river water for cooking, drinking, and washing. I carry toilet paper with me and when I finally got permission, I took it with me. When I returned, several Cuna boys came running up

"If you want people to respect you, you must show them your respect. I had to learn this in the jungle from so-called savages. When I travel I never carry a weapon. If you go into a jungle with firearms the people are afraid of you, because they know you can kill at a distance. To them a gun is worth a lot of money. I have been in places where someone would slit a person's throat for three dollars, but I have yet to be in a place where you can buy a gun for the same price."

Danny and Manuel made it into Uala Indian territory, a forbidden stretch of jungle. When they arrived at an Indian village they were held prisoners and put on trial. Danny had violated a law by coming into this part of the jungle without permission, and Manuel was in trouble because he had guided him. Manuel was taken away during the first part of the trial and when he returned he was bathed in sweat and his face was masked in pain.

"After a long trial they finally asked me what position I held in Niobrara. My fate and possibly my future hinged on the answer. Finally I shouted out, I am president of the Niobrara Community Club'. A look of awe swept over their faces, and I knew I had said the right thing. I don't know what they did to Manuel, as I never saw him again after the trial, but they let me go."

The next morning an old witch doctor named Mastali and his son led Danny through the jungle. The two men became friends during five lazy days floating the river fishing, swimming, (Continued on page 51)

34 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1970 35

A Country Kind of Spring

This season of calves and colts brings bustle of activity to Sand Hills

WHEN THE SNOW begins to melt and the valleys become huge patchwork quilts of shrinking drifts and widening circles of greening sod, and every dip and hollow holds a blue mirror of water, we know spring has come to the Sand Hills. The meadows are alive with the green and white flashes of hundreds of mallards that wheel and dive and splash gracefully in the lakes, ponds, and puddles, filling the air with their gladness.

What special spark makes a country spring so much more vital and alive than the city season? Perhaps it is simply awareness. Here there are no distractions to keep us from enjoying the redwing blackbirds flitting in the cottonwoods, or listening to the first tentative trillings of the meadowlarks, or watching a close wedge of geese honking across the sunset. We can appreciate the radiance of twilight when everything is suffused with pale gold, so unique from the bright tones of autumn or the eggshell tints of winter sunsets.

Best of all the season's excitements though are the new babies. Little toddling calves with such never-again white markings on bright red curly coats hide behind their mothers in the calving lot. From the first timid and wobbly steps to the know-it-all attitude of a few days later, their every moment is a delight to watch. Of course, there are always a few problems and a hectic schedule in connection with calving time. All the "heavies" (very expectant cows) are (Continued on page 64)

STRAIGHT FROM THE BURROW

Debonair comic of the plains sets the record right in an exclusive interview with NEBRASKAland

BOY, WAS I ever surprised when I got this phone call from a NEBRASKAland writer asking for an exclusive interview. Not that it is so unusual for a prairie dog to get a phone call, I was just amazed that I was selected since there are so many Phineas T. Prairie Dogs listed in the book. It must have been the Esquire behind my name that did the trick.

Anyway, this writer says, You prairie dogs are supposed to be the comedians of the plains. What makes you so happy? Tell it like it is."

Well, I invited her down to my burrow, but she just muttered something about not being able to get a round "Peg" in a square hole and asked if I would meet her topside. I agreed and we set a time to meet at my lake-front home at Red Willow Reservoir,

Well, what started out as my simply being

a consultant on the story ended up with me

writing it. What that kid didn't know about us

prairie dogs would have filled the burrows of

the world. She just sat around and kept asking

me to do something funny. In exasperation, and

mainly because I'm a firm believer in the literary school that says a writer should live what

he writes, I offered to do the story for her. After

all, it would be infinitely easier for me to turn

writer than for her to turn prairie dog. So, we

worked out a solution —I would dictate, she

would take it all down. Not that I am incapable

of writing, it's just that I choose not to. Oh,

sure, once in a while I'll drop a postcard to my

cousin in Weeping Water, but for the most part

We prairie dogs are widely known for our rather dapper appearance — our fur coats are a lovely reddish hue, that, I'm very glad to say, does nothing fashion wise for the wearer unless he, too, is a prairie dog. Hence, we have no problem with scalawags trying to knock us off to cover the back of some woman in Paris. Our roly-poly appearance doesn't show it, but come impending doom, we can scamper at a second's warning. We pride ourselves on our fine physical shape. What you people have assumed is just good-natured scampering and frolicking are in reality part of a rigorous physical-training program. You have to be in top shape to escape hawks, owls, ferrets, and a lot of other predatory characters. All of this, plus our eyes, which have been called liquid, vivacious, warm, and appealing by more than one amorous buffalo, makes us the most sought-after dandies on the plains. If I had to choose one word to encompass the "prairie-dog look", it would simply have to be handsome, although debonair does run a close second. But enough of this.. .when you see us, you will have no difficulty in recognizing us as we are the only couth animal on the prairie. Honestly, the way buffaloes take care of themselves! I don't warit to say what their problem is specifically, but you never have any trouble locating a buffalo if your olfactory sense works properly.

As for this comedian of the plains tag, we didn't realize that we were the comedians. We always thought you humans were the funny guys coming out to entertain us. But if you

However, we do have our gripes. Like holes, for example. We get blamed for every hole dug in America. Why, it is getting so bad that we don't even visit the Grand Canyon for fear of being blamed for that, too. We don't just go around digging holes to bug humans. In fact, if you ask us nicely to move on, we usually do. Since you people came to the prairies, we have been continuously on the move trying to get out of your way.

Another thing, this poison you keep leaving around our towns. Someone is likely to get hurt if you keep flinging it around so carelesly. Perhaps some of you feel ill will toward us, but I'll let you in on a secret —that poison is so effective in controlling us that you don't need to go hog-wild with it and exterminate us. Even the government recognizes our plight and says we are close to being an "endangered species". I don't know what that means exactly, but it sounds pretty grim. How long has it been since you have seen a black-footed ferret? Quite a while, you say? They are our natural enemies, so I hate to say anything in their defense, but they, too, are an "endangered species", because we are. If you exterminate us, you exterminate them, too, and there's no telling where the vicious circle will end.

And one more request. How about changing the stupid name of prairie dogs? It just doesn't have any class or zing. Maybe it would help our image if we could come up with some neat name like miniature prairie gazelle or prairie antelope, both sleek-sounding names which would make as much sense as our present monikers. After all, and this is a family secret, we, are rodents instead of canines, Frankly, I've always liked the sound of prairie schooners —sleek, strong, hardy. My grandpuppy, Joshua, used to tell me he greeted the first prairie schooners that passed this way.

All in all, though, I guess we do have a pretty good life. In what other society can you get a three-room burrow rent free? And even the buffaloes agree that we prairie dogs have the best dust wallows in the United States. We have no violence or psychiatric problems to contend with because when we feel like getting out and barking, we get out and bark, which is always good for the soul. In fact, the next time you're depressed, why don't you drop into our community? We don't promise to cure ingrown toenails or poverty, but a good bark or two now and then sure clears the air. THE END

THE LAST BIVOUAC

Born during the Indian wars, Fort McPherson was a bulwark on the frontier. Its residents now sleep in honor under the quiet rows of marble markers

THEY CALL it Fort McPherson National Cemetery and the unknowing ask why the "fort" in its name. There are no martial trappings there except for Old Glory waving above the ordered monuments. Monuments that mark the last bivouac of more than 3,000 Americans who fought and died for their country.

The significance of the word, fort, dates back to October 13, 1863, to be exact, when men of Company F, Seventh Iowa Volunteer Cavalry rode up to a spot 9 miles east of the junction of the North and South Platte rivers. They went to work in a hurry, for trouble was close—Indian trouble.

It had started the year before with Indian raids in Minnesota and had spread south and west like prarie fire. The red men were on the war path and the whole Platte Valley was theirs for the pillaging. The hard-bitten troops of other years who had guarded the valley were off to the Civil War, and the Indians knew that now was the time to drive out the hated whites for good. True, Fort Kearny did offer some protection to the settlers, immigrants, and freighters who lived on or traveled this traditional route. But, it was 350 long miles from Kearny in the east to Fort Laramie in the west and their tiny garrisons could not guard all the trail against the hit-and-run tactics of the hostiles.

Somewhere in between there had to be another block and another obstacle to the Indians, and so the future Fort McPherson was established, 18 miles east of the present city of North Platte. Company F did not call the post a fort, not yet. Its men were too busy cutting red cedar in the nearby canyons and turning the logs into barracks to trifle about names. Winter was coming and they had to get under cover as quickly as they could. The thinkers among them could see the strategic importance of the new post, first called Cantonment McKean, but for most of the troopers the place was one of plain hard work with buck saw, cant hook, and ax. It was kind of nice to know this new post was named in honor of General Thomas McKean, commanding officer of the military district, but such knowledge didn't take the sting out of blistered hands or the grumble out of hard-case sergeants.

The post was well located. There was a good spring At a nearby ranch which insured a stable water supply and plenty of red cedar in the canyons for lumber and fqel. Even more important to the military minds was its proximity to a major Indian crossing of the Platte. Besides, the post's Central location made patrolling of the side trails that fed into the main valley relatively easy.

After the barracks were up, the Seventh turned to building a guardhouse,"a bakery, stables, supply depots, a hospital, a headquarters, and all the other construction a frontier post needed to be fairly self sufficient. Indeed, building, rebuilding, (Continued on page 63)

The Alarming Case Against DDT

In recent years, environmental scientists have documneted an enormous - and enormously menancing - body of knowledge concerning the worldwide side effcts of DDT

Reprinted with permission from the October 1969 Reader's Digest Copyright 1969 by The Reader's Digest Association, Inc.DURING the last year, "the great DDT controversy" has gone worldwide. Opponents of the insecticide, convinced it is doing harm to our environment, have succeeded in getting it banned in Sweden, Denmark and Hungary; in the United States, Arizona and Michigan have outlawed it, and dozens of cities, including New York and Chicago, have abandoned it as a tree spray. Now there is increasing pressure for nationwide banning, both here and abroad.

But many farmers, scientists and government officials still say that the banning of DDT is a panic reaction to unproven charges, and that it will do far more harm than good. Their argument is this:

DDT is among the cheapest and most easily applied insecticides. It has saved millions of lives through the prevention of insect-borne diseases like malaria, typhus and encephalitis. It has been proved harmless to man, and the damaging side effects claimed by conservationists - the killing of wildlife and even the approaching extinction of some species - either have been due to other causes or have been relatively minor compared to the chemical's economic and humanitarian benefits.

One extremely influential factor in DDT's future will be a decision soon to be reached by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Scientists and politicians around the world are waiting to see which way Wisconsin goes, because earlier this year that state held the first full-fledged public "trial" of DDT-27 days of hearings at which the country's leading authorities on the subject testified under oath and were cross-examined by attorneys for both sides.

Opposing DDT in Wisconsin were local conservationists and a group of scientists called the Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. (EDF), whose aim is to fight strategic test cases in court that will establish the legal right of the people to an unspoiled environment. Defending DDT was a task force of the National Agricultural Chemicals Association, a trade group.

After attending several days of the hearings, I discussed the major issues in the DDT controversy with one of the men most responsible for bringing it to the fore: Dr. Charles F. Wurster, a 39-year-old assistant professor of biology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, who is one of the founders of EDF and is chief expert on DDT's worldwide side effects.

Q. Dr. Wurster, you've been spending most of your time for the past six FEBRUARY 1970 years campaigning against DDT. What got you so involved in the problem?

A. In 1962, when I was a research associate at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., several other biologists and I decided, purely as a spare-time project, to study the effects on the local bird population of the spraying of elms with DDT. We'd heard reports of bird mortality from elm spraying, but we were quite unprepared for the number of deaths our study revealed. Hundreds of birds died, including 70 percent of Hanover's robins.

Q. But many scientists say it's irresponsible alarmism to take an incident like this—even if it is repeated on a local basis in hundreds of other places — and blow it up into a picture of worldwide killing. In fact, that's their main criticism of Rachel Carson's book, Silent Spring, which was the most influential single factor in starting the movement against DDT.

A. You have to understand that DDT does its damage in two distinctly different ways. One is what happened at Hanover —the creation of intense, very localized "hot spots," where animals are directly killed by the high concentration of DDT in the environment. Here the harm is sudden and dramatic, and the cause is easy to identify.

But when this local concentration of DDT spreads out into the rest of the environment, the levels become much lower and the effects far subtler and harder to discern. The affected animals are spread over large areas; often they're out of sight — out in the oceans or in wild areas infrequently visited by man —and the harmful changes come slowly, over a period of months or years.

Now, when Rachel Carson did her research, in the late 1950s and early '60s, the evidence of even the first kind of damage was often hard to find; and there was even less evidence of the second kind. But in the years since Silent Spring was published, hundreds of environmental scientists all over the world have begun studying the side effects of insecticides.

They've measured DDT in all kinds of animal species, from plankton and clams in the sea to penguins, seals, crickets, frogs and man. They've fed DDT to birds and fish and observed the effects on the eggs they laid and the offspring that were — or weren't —hatched. They've analyzed samples of soil, water, air and rain at thousands of places all over the world.

Based on all this research, they have published a truly monumental body of the kind of evidence that was lacking when Miss Carson wrote. And what all this information tells us is that she was right in almost everything she said. As one of the scientists at the Wisconsin hearings said, "I'm scared." The danger is no longer debatable; it's established, scientific fact.

Q. What do you regard as the most important of these "nondebatable" facts about DDT?

A. First, DDT is an extremely longlasting chemical. The insecticide Parathion is far deadlier than DDT, but on an environmental scale it's much safer because it loses its potency in just a few days. If a man applying Parathion to an apple orchard gets a drop of it on his sxin, it could kill him; but a few weeks later you could safely eat the apples he sprayed.

DDT, on the other hand, persists for years in the environment without losing its potency. It probably has a half-life of several years; this means that if you spread two pounds of it on a field today, and none washed away, in 10 or 15 years you could still have a pound of active DDT in the soil.

Second, there is no way to prevent DDT from spreading around the world. In fact, the main application method — converting it into mist-like particles that float in the air —guarantees that much of it will be circulated wherever the wind takes it. Measurements of DDT sprayed from a plane showed that about half of it did not reach its target on the ground.

But even if it all did hit its target, it would still spread throughout the environment. The rain washes it into rivers and oceans, and it vaporizes into the air and is blown away. It's the most widespread pollutant we have; you and I are breathing it now, and tonight we'll have it with our dinner.

Third, being a nerve poison, DDT can kill anything with a nervous system, but the necessary dosage varies from species to species. For instance, when we discuss doses of DDT we usually talk in terms of parts per million — ppm — which is the number of grams of DDT per million grams of the water, air or animal tissue in which it is found. It takes 50 ppm in the brain of a robin to kill the bird, but one tenth of that amount will kill some fish; pheasants and herring gulls, on the other hand, can sometimes store thousands of ppm in their bodies without lethal effects.

Q. This question of parts per million brings up a major point made by the defenders of DDT. In the whole environment, you'll find such high doses of DDT, only in the relatively few "hot spots" near sprayed (Continued on page 62)

47

HOME-GROWN PEOPLE-STOPPERS

Every Nebraska community has something to boast about. Developing these attractions requires imagination and work

EVERYONE WOULD like to get something for nothing, otherwise "con" men would starve. Unfortunately, very little is achieved without thought, patience, and old-fashioned hard work. And that cruel fact of life applies to tourist attractions as well. Elves, leprechauns, and fairy godmothers cannot do the job. A successful attraction will not magically appear. Money helps, but even millions of dollars cannot guarantee success, nor are such funds essential to the creation of an appealing people-stopper.

Disneyland is nice, but such grandiose attractions are hardly realistic for the average NEBRASKAland community. What then is the answer to the dilemma? The solution is really very simple. One need only open his eyes and ears and look around. Even the community that had "nothing to attract visitors" does have some interesting attribute on which to capitalize. What do guests want to see when they come to visit? Maybe it's an unusual building, an old-fashioned country store, a herd of Herefords, or a windmill.

Tourists are strange people. It doesn't take a million dollars or fantastic mountain ranges to interest or delight them. They are intrigued by the unusual, the offbeat, and the colorful, and often what may be commonplace to the native Nebraskan can be completely new and exciting to the visitor.

Many "city dudes" have never seen a cow or a pig or a chicken... except as steaks and chops and drumsticks in their local market. Consequently, they are fascinated by an ordinary farm or ranch. A miniature barnyard in a village park could well lure travelers into a community and keep them there for a few hours.

Down in Kansas, the folks at Greensburg have made a booming attraction out of the "world's largest hand-dug well". Certainly, Nebraskans can equal their neighbors south of the border. Of course, once an "attraction" is spotted, it will require promotion and advertising. People can't stop if they don't know something is there.

NEBRASKAland is rich with possibilities for "home-grown" attractions. And, events have their potential as well.

Many communities have already scratched their collective heads and come up with some exciting tourist draws. The Swedes and Czechs have capitalized on their ethnic heritage with festivals at Stromsburg, Wilbur, Schuyler, and Dwight. O'Neill's Irishmen have appropriated St. Patrick's Day for their own special brand of festivities. And, Valentine had the heart to take advantage of Valentine's Day to spread the word on that community.

Obviously, some towns have a slight advantage. They have had the nucleus for prime attractions handed to them. Of course, they must recognize the possibilities and make the most of them. Many have done just that - North Platte with Buffalo Bill, Ogallala as the Cowboy Capital, Gothenburg with the Pony Express, Red Cloud with Catherland, Gering with the Oregon Trail, Grand Island with the pioneer. And, there are others.

On the other hand, some communities must really dig to come up with an idea. But it can and has been done. Kimball has capitalized on its strategic location in the center of the intercontinental missile network and in the heart of Nebraska's oil country. Plans are even afoot there to build a multi-million dollar missile museum, an outgrowth of a small, but good, idea.

One of the greatest success stories in Nebraska comes from Brownville. This Missouri River village was all but gasping its last when some dedicated folks decided to pump some new life into it with injections

However, any endeavor requires plain, old-fashioned hard work, whether the town starts with something or nothing.