WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

December 19 50 cents

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

NEBRASKAlandLIKE IT IS-"I am sure M. O. Steen's article, The Pheasant's Destiny, in the July 1969 NEBRASKAland will be a source of controversy for many. Please add my name to the list of hunters who agree with your principles of game management. My years of hunting have taught me the facts as you summarized them. I, for one, will continue to tell it like I believe it is." —J. R. Olson, Billings, Montana.

TO THE POINT - "The Pheasant's Destiny by M. O. Steen in the July NEBRASKAland was direct and to the point. It also told the straight truth. I wish that every hunter in this state could have the opportunity to read this fine article, maybe then something would be done for the pheasants, quail, and rabbits which we all like to hunt." — Bernie Proskovec, Omaha.

GOOD EATING-"I read the August Speak Up about freshwater mussels (clams) and here is a recipe for preparing them.

"Put the clams in a large pail of cold water and keep in a cool place. Change the water twice a day for three days. This allows for the explusion of waste materials. Then drop the clams one at a time in very hot water. When the shells open slightly, remove the clams from the water, insert a long, sharp knife and cut the side muscle connecting the two halves. Remove the meat, cut away the DECEMBER 1969 green or black wastes, and cut the meat into small pieces.

"Place the pieces and 1 cup of water in a pressure cooker and process for 20 to 30 minutes. The liquid should be saved to add flavor to soups or chowders. Grind the cooked chunks and use in clam dip, clam chowder, casseroles, or freeze for future use.

"Here is a recipe for a rich and delicious clam dip: Ground cooked clams Salad dressing Minced onion Onion salt Grated American cheese 2 to 3 tablespoons of sour cream. Amounts vary according to number of servings!" —Mrs. Vayden Anderson, Stromsburg.

BIG WINNER-"The 1969 All-State parade in Ontario is history and our efforts to publicize our native state of Nebraska were rewarding, for we won the very lovely president's trophy. There were almost 200 entries.

"Our section in the parade was ushered in with a huge sign, NEBRASKA WELCOMES YOU. Behind it was a young boy carrying a huge, green box, with a large ear of corn on the front of it and the words CORNHUSKER STATE.

Right behind the grand marshall came our queen, Miss Gerry Faubel of Norfolk, in an old-fashioned surrey with fringe on top.

She was followed by her princesses in a blue convertible decorated with blue and gold flowers. Then came a buckboard filled with square dancers covered

SOURCE OF PRIDE-'The picture of an old soddy in the March 1969 NEBRASKAland prompted me to write of my family's early experiences in Nebraska. My father and 2 of his Civil War companions of Company D, 39th Iowa Regiment came to the state in 1871.

They left Clark County, Iowa in a prairie schooner, ferried across the Missouri River at Nebraska City, and headed for Lancaster, now Lincoln. When they reached Lancaster it was only a dreary salt basin, so they went on west and south to the Little Blue River country where there was running water and timber.

"The trio staked out three claims and went back to Iowa for their families. On their return to Nuckolls County in September, they began building cabins out of black-walnut logs.

"I came along in 1874, the year of the grasshopper. My mother went through the ordeal of delivery without a doctor or a trained nurse. Fifteen years later, we moved to a farm near Lincoln where I went to high school and then on to the University where I graduated as a Phi Beta Kappa in June 1900.

"It has always been a source of pride for me to describe to others the Capitol Building, the Unicameral legislature, Nebraska's crops, the state's irrigation system, and the good professors I had at the University." —Mrs. Grace C. Jones, Berkeley, California.

A CREDIT —"A friend of mine sent me a subscription to NEBRASKAland. I find it a great magazine, and certainly a credit to the great state of Nebraska. Keep coming with those western tales." — R. G. Scharbach, Madelia, Minnesota.

WINNER—This poem won second place in the 1967 Centennial Writing Contest sponsored by the Blair Public Library." — Mrs. Sylvia S. Peirce, Farnam.

IN GRATITUDE From across lands and seas They came here, Seeking refuge in this prairie haven, Freedom to live a free mans life. Helping to build a nation wide And safe from rank appression. They fought here for law and order and equality, For rights, and a decent chance for progress. Theirs were our firm foundations Laid by hard work, hope, and earnest prayers That our birthright might be The reality of their dreams and aspirations. One hundred years or more Have passed since into eternity. They lie now in their graves Beneath the prairie soil they knew and cherished Even to every blade of grass and leaf. The time has come when we must pause, Lift up our hearts in gratitude, For their forbearance, for their Gift of themselves in our behalf, Their willingness to sacrifice, And their deeds for future's sake. O hardy pioneers, we give you thanks.

Roundup and What to do

December is gift-wrapped bundle of thrilling hockey and holiday season treats

NEBRASKA RINGS in December with a gift-wrapped array of special holiday activities from fireside-tree decorating to outside snow-tramping. Among the season's more active events are the Omaha Knights' icehockey thrillers, and on hand to give the goalie some tips is Miss Judy Dowding. Judy is especially qualified as an advisor because she is majoring in recreational leadership at the University of Nebraska.

The daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Dowding of Seward, Judy is a 1969 graduate of Seward High where she was a cheerleader. She was chosen Nebraska Junior Miss in 1969 and was Seward's Homecoming Queen in 1968. Last summer she was a student advisor for the State Student Council Leadership Workshop held in Lincoln. She lists swimming, water skiing, cooking, sewing, bicycling, ice skating, sledding, art, and music among her hobbies.

Holiday traditions are part of December in NEBRASKAland and for the 23rd time Minden will present its "Light of the World" pageant on two sides of the courthouse. The presentations will be on the 7th and 14th. The

Hemingford's famous diorama signifies, too, the deeper meaning of Christmas. Nativity scene after Nativity scene brings home the spirit of the holiday.

As it has in years past, the State Capitol will sport a Christmas tree in the rotunda. A holiday program is also scheduled but the date is not firmed up.

Basketball, accented by holiday tournaments, rides high on the December action charts. Nebraska University will host four teams of roundballers. The University of California at Irvin will be the Cornhuskers' rival on December 1, with Duquesne coming in eight days later. The 20th and 22nd will see the invasion of Lincoln first by Arizona, then by Wyoming. Numerous high school and college teams throughout the state will also display their cage skills to spectators.

For upland hunters, December offers plenty of gunning with its still-open pheasant, quail, squirrel, and rabbit seasons. Geese will be fair game until sundown of Christmas Day, and an experimental-duck season will add its outdoor pleasure to the hunting calendar on December 13. (Details on this experimental season are on pages 40-45).

Archery and firearm-deer seasons are open, too. In the De Soto Unit, a waterfowl refuge, a special late deer season is scheduled for December 27 and 28. The hunt serves two purposes — to please hunters and to control the area's deer population. This year only permit holders will be allowed on the area. Statewide, archers will have all month to try their luck at bringing home the venison.

If the weather cooperates, ice fishing can furnish plenty of thrills, for there are plenty of scrappers still lurking in the lakes.

Music, theater, and art will provide rich enjoyment for the culturally inclined. Sheldon Art Gallery in Lincoln lists a Christmas art fair in the Art Shop from the 2nd through the 21st. Drawings by Fritz Bultman and paintings by Jannis Spyropoulos will remain in the gallery through December 7. Meanwhile, at Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, a Picasso exhibit will open December 7. Selections from the famed Lawrence-Myden Foundation collection are scheduled for a full month's showing at Joslyn, too. On the 14th the Japanese, Netsuke, will exhibit along with the week-long ''Contemporary prints for Christmas giving".

In the world of drama, Lincoln's theaters will ring with "A Thousand Clowns", a Community Playhouse production. There is laughter for each clown in the title on the 5th through the 7th and again on the 12th and 13th. The University of Nebraska theater presents DECEMBER 1969 "The Rose and the Ring" while the Nebraska Wesleyan players perform "It is So, If You Think So".

In Omaha, the Playhouse presents "The Great Sebastians" by the authors of Life With Father. The show is especially timely in view of current Russian-Czech tension. A mind-reading team outwits the Soviets in occupied Czechoslovakia, creating an atmosphere of suspense, laughter, and magic.

Music will ring glad tidings throughout the state with numerous community concerts. The University of Nebraska's Choral Union will present selections from "The Messiah" on the 14th. The Concordia Cappella Choir will give a Christmas concert on the 6th and 7th, and the University Singers will combine their voices in a carol concert on the 8th.

At Joslyn, the Chamber Music series hosts the Marlborough Trio on the 7th. It will be followed by Giorgio Tozzi who will perform there on the 9th.

So whatever your taste, from the harmony of cultural activities to the hard-hitting action of sports, NEBRASKAland has pleasure aplenty for residents and guests alike.

What to do 1 —Nebraska vs. University of California at Irvin, basketball, Lincoln 1-14 —"The Great Sebastians", Omaha Community Playhouse, Omaha 2-21 — Annual art fair, Sheldon Art Gallery, Lincoln 5 —Omaha Knights vs. Oklahoma City Blazers, ice hockey, Omaha 5-7 — "A Thousand Clowns", Community Playhouse, Lincoln 6 — Golden gift days, Imperial 6-7 —Cappella Choir Christmas concert, Concordia Teachers College, Seward 7 —Picasso, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha 7 —"Light of the World" pageant, Minden 7 — Marlborough Trio, Joslyn Chamber Music se- ries, Omaha 8 —University Singers carol concert, Lincoln 9 —Giorgio Tozzi, Joslyn Tuesday musical, Omaha 9 —Nebraska vs. Duquesne, basketball, Lincoln 10-13 —"The Rose and the Ring", University theater, Lincoln 11-14-"It Is So, If You Think So", Nebraska Wesleyan University theater, Lincoln 12 — Omaha Knights vs. Fort Worth Wings, ice hockey, Omaha 12-13-"A Thousand Clowns", Community Playhouse, Lincoln 13-Jan. 4 —Experimental duck season 13 — Golden gift days, Imperial 13 —Omaha Knights vs. Dallas Black Hawks, ice hockey, Omaha 13 — State Make-it-yourself-with-wool contest, Lexington 14-'The Messiah", University Choral Union, Lincoln 14 —"Light of the World" pageant, Minden 17-20-"The Rose and the Ring", University theater, Lincoln 20 — Golden gift days, Imperial 20 —Omaha Knights vs. Dallas Black Hawks, ice hockey, Omaha 20 —Nebraska vs. Arizona, basketball, Lincoln 22 — Nebraska vs. Wyoming, basketball, Lincoln 25 — Omaha Knights vs. Iowa Stars, ice hockey, Omaha 25 — Goose season ends 26-28 —Holiday basketball tournament, Arapahoe 26-29 —Holiday basketball tournament, Omaha 27 —Omaha Knights vs. Tulsa Oilers, ice hockey, Omaha 27-28 — De Soto Bend deer season 29-30 — Kearney State holiday basketball tournament, Kearney 31 — Omaha Knights vs. Kansas City Blues, ice hockey, Omaha 31 —Archery deer season ends All month — Pheasant, quail, rabbit, and squirrel hunting. THE END

I WAS SHOTGUNNED

MY HUNTING COMPANIONS filled the still winter air with roaring laughter as I landed on my backside in the gooey mud of a milo field near Minden. But, the sting of more than 80 No. 6 pellets in my legs from a wayward 12-gauge Magnum made the situation far from humorous for me.

My companions, of course, didn't realize that I had been shot. They thought my flailing and yelping was a rather successful attempt to salvage some humor from an accidental flop in the mud. Only after an agonizing crawl of about 100 yards to the car did the blood on my legs tell them I wasn't joking.

It all started on a December morning in 1967, when I took off from my home in Kearney with two companions in hopes of bagging some ringnecks. By 2 p.m., however, it became obvious from our nearly empty game bags that we were doing something wrong. A change of tactics was clearly in order, so we decided to switch hunting operations from cornfields and shelterbelts to cut milo fields.

About seven miles south of Minden, we spotted a likely looking spot and made plans for the hunt. One companion, who had hurt his foot earlier in the day, elected to drive the car down the road to the end of the field, while I walked it with the other hunter. Stomping through the muddy field with its treacherous footing was hard work and quite unproductive.

Then, as we entered a weed patch about 100 yards from the end of the field, a big rooster boiled out of the cover between my companion and myself. The ringneck was directly in line with the other hunter and fly ing right toward me, so I decided to hold my fire until he passed over or veered away.

Meanwhile, my companion, about 100 feet away, was jerking the trigger on a snap shot, apparently without seeing me or without considering my position. The charge from his Magnum 12 lifted me off the ground and dumped me in the mud. On the way down, I dropped my shotgun and it discharged harmless ly into the air.

For a few seconds, I didn't know what had happened. I felt the stinging sensation in my legs, but I thought the pellets had bounced off. Then I saw the holes in my trousers, and the stinging turned to real pain. That started the yelling and jump ing that so amused my companions. When the only response to my plea 12

In this manner, I passed the hunt ing partner who had shot me. Nearly hysterical with laughter one second, his jaw was hanging ajar the next as he saw the blood-and-mud mixture on my legs. He just stood there shocked as I continued to grope to ward the car.

When I finally crawled in, the driver was still laughing, but a look at my legs and a glance at the pain and anger on my face stopped his guffaws pronto.

Meanwhile, the other hunter had recovered at least partially from his shock and had started back into the field after my gun. We yelled at him to forget it and started for the hospital in Minden as soon as he was aboard.

I made the seven-mile trip in the back seat with my feet out the window while the driver battled sloppy country roads. After what seemed like a hundred miles and after near ly getting stuck several times in mudholes and ruts along the way, we arrived in Minden. I was offered a stretcher at the hospital, but I waved it aside, saying I would walk. I stepped out of the car, found my legs wouldn't work, and fell flat on the ground, wincing from pain and embarrassment.

Once inside, X-rays showed more than 80 No. 6 shot in my legs, plus a few in my arms and chest. The doctors removed the ones from my arms and chest and about 10 from near my kneecaps. The rest were left in my legs, since digging into the muscles 80 times would cause even more damage.

I was hobbled for several weeks by the wounds, but today, I experience only occasional swelling of the knees and some pain in my legs. The incident was a crystal-clear lesson for my friends and a painful reminder to me regarding gun handling in the field. I still love to hunt, but when I go out, I make sure all of my companions are safety conscious.

Aside from the intermittent pain and swelling and the pointed safety lesson, the only after-effect of that incident near Minden is a joke among my friends, with me as its object. I don't dare lag behind, whether hunting or just hanging around town, without the risk of someone yelling, "Hey, Toby, get the lead out." I have to admit, it's pretty humorous, and I always get a chuckle out of that crack. But two years ago, I wasn't laughing. THE END

A Country Kind of Winter

Serenity is snowbound in this Sand Hills season of placid harshness

HAVE YOU ever seen winter? I don't mean the unhappy winter of a city's dirty snow, slushy streets, and cold, frozen-faced people hurrying toward warmth. I mean the country kind of winter, where your own footsteps make the first marks in an otherwise unbroken blanket of snow.

Let me tell you what winter is like here in the Sand Hills ranch country of NEBRASKAland. The ranch road lies in a valley, and it isn't plowed very often, so instead of being impatient at the inconvenience of keeping to the higher ground where the snow is blown away, we look at the drifted road as a symbol of the season and accept it as part of winter's charm. Ifs a charm that includes the face of the land on a cold and frosty December night as we make our way to the schoolhouse for the annual Christmas program. We cut fresh tracks across a foot of crusted snow, and the headlights pick up the loping form of a coyote, or the sudden dart of mice scurrying out of our path. We see a jackrabbit huddled in the curve of a drift, keeping watch for the preying shadow of a great- horned owl.

Our night is clear and the stars are as close as the frosted windows through which we peer. The wind is at a lull, resting from the effort of whipping and piling the snow in fantastic sculptures of every conceivable shape. Moonglow has softened and blended the roughness of (Continued on page 51)

"HOW ABOUT TOMORROW?"

Though not easy as pie, Christmas season hunt is father and son's pudding

WE WERE ONLY 50 yards from the station wagon when Doug held up his gloved hand and wiggled his numb fingers with a grimace of pain.

"If that boy's enthusiasm for hunting is still high after today, he'll make a real hunter," I mused.

"Carry your shotgun under your arm and keep your hands in your pockets," I advised. "If your fingers get frostbitten, you are in trouble." We were on the second Saturday of a Christmas-vacation quail hunt

Normally, Doug and I hunt around Lincoln, but we had tired of combing the same old covers and wanted to see some new territory. I had heard of the excellent quail hunting around Swanton and decided to give it a try. We didn't do exceptionally well on our first expedition, but we did find enough birds to warrant a return trip.

Although Doug, 16, has hunted with me since he was a sprout, he didn't get really serious about wing shooting until the 1968-69 season. Gradually, the youngster was acquiring bird sense. He was learning to ignore the startling roar of a rising covey and to target in on one bird instead of flock shooting. Doug was also getting better at estimating the bird-holding potentials of different cover types and to position himself with an eye to flush routes. On our earlier hunt, he had bagged two bobs over dogs and found the

We had two dogs. Fritz, a German shorthair, was more eager than experienced, while Chief, an 11-year old springer, had the confident air of a veteran even though he was relatively unfamiliar with quail. The pair belonged to John Kurtz of Lincoln. I met John through a mutual acquaintance and discovered we had sailed the same waters during our World War II navy stints. He shares my love for hunting so we got along famously. Before his transfer to the Capital City my new friend lived in western Nebraska where quail are relatively scarce, so bob hunting was a real treat to him. He accepted our invitation to go along.

I'm long and lanky and can bite off a yard of real estate with every stride, so I didn't realize that Doug was humping to keep up as we mushed through the deep snow. Doug is pretty husky for his age, but he's a long way from his full growth and his shorter legs were scissoring about twice as fast as mine as we trudged across the bitterly cold prairie.

Little clouds of vapor were jetting from the boy's mouth as he puffed along. Suddenly, I realized that my 18 son was practically panting. Although he wasn't complaining, I stopped.

"How you doing, Doug?"

"Pretty good. I'm warm now except for my ears and fingers. We heading for the multiflora?"

At my nod, the boy broke his double-barrel and glanced at the 20-gauge shells nestling in the cham bers. He closed the gun and double-checked the tang safety. Following his example, I checked my slide action 12. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw John doing the same with his 12-gauge "corn sheller".

The multiflora formed a sprawling "L" along two sides of a grassy patch between two fields of harvested milo. We had spooked birds there the week before, so as we moved in I searched for tracks. I had just picked up their lacy fretwork in the snow when the dogs went birdy.

Our covey was there, but it didn't hold. John was cautioning the dogs to hold in when a host of brown forms spattered the shining sky. I jogged forward, hoping to mark the bobwhites down.

"They went into the grass on that far side," I yelled to my companions.

"Doug, get up here behind the dogs and work the singles," John ordered as he heeled the dogs. My son was eager now. His face, already rosy from the cold, was positively glowing with anticipation as he hurried up, his little 20 held high. The dogs were having trouble sorting out the confusion of scents that eddied from the frozen ground.

Fritz, the shorthair, was displaying his inexperience. Twice he false pointed to send our blood pressures soaring, only to break and inch forward. Chief was more thorough. He padded away, his stub tail vibrat ing like a metronome as he nosed along.

The bobwhites were running under the snow with out revealing their presence to the eye, but the dogs were getting closer and closer, and I knew it would be only minutes before the birds were pinned. Suddenly, the shorthair staunched and the springer, growling low in his throat, reluctantly backed him.

"What's he doi - ?" Doug's voice trailed of? as two bobs jetted up and banked to the boy's right. Doug swung, shot, missed, and shot again. Then John and I got in the act as other birds went up. After the echoes died away, we took stock. The only thing in the snow was a scattering of empty shotgun shells.

Doug was pretty low. "Two perfect shots and I goofed them both."

"Don't feel bad, your dad and I didn't cut any feathers, either," John consoled him.

I figured the birds had dropped into the milo ahead, so I suggested we hunt it out and then head for a woody draw some 300 yards away. We had kicked our way over some 20 to 30 rows when Fritz and Chief made birds. My eyes were on the dogs, and I wasn't expecting a sleeper that spurted from under my boot. My first shot shifted the bird into high, the second into passing gear, and the third made him cut in his after burner, but that was all.

Doug was watching me and got caught flatfooted when a bob whirred up in front of Chief. His two shots were close to the fleeing bird, but not close enough. Two more bobs lifted at the reports and John rode one out to cartwheel him into the snow with a blast from his 12.

The four misses took some of the tuck out of Doug. There was a glisten to his eyes that didn't come from the cold as he plucked the empties from his double and replaced them with live rounds.

I knew he was discouraged and I vowed that I would get him into more birds if I possibly could. The NEBRASKAland

"John and I will take the dogs and work the bottom while you skirt the bank above. If we spook a covey, some birds ought to flare out toward you or tower above the trees. Keep just a little ahead of us and be ready," I told Doug.

We were sliding over the lip of the draw when a cottontail burst out and dashed up the slope toward my son.

John's "Bunny on the way" was punctuated with the sharp spat of the 20 and a delighted, "I got him!" The snow was fluffier in the bottom of the draw and it wasn't long before I picked up the tracks of a foraging covey. John and the dogs pinched in at my hail, and it wasn't long before a heavy covey sizzled up from under the protective branches of a fallen tree to scatter in a dozen different directions. I saw two birds heading for Doug, so I turned toward one that was towering straight away. My 12 boomed and the bob folded, a DECEMBER 1969 little whisp of feathers following him down. Doug's happy yelp told me he had scored, too. Both of our kills were fine, plump bobs and we held a mutual admiration session before tucking them away in our game pockets.

John had pinpointed the escaping covey. "Some birds went back over us and went in behind us. Others went straight down the draw. Why don't you and Doug push them out, while I and the dogs try the back track ers?" he suggested.

His plan worked well. Doug joined me in the bot tom of the draw and we eased along, looking for tracks. My son followed up a single and centered him when he flushed. I tracked a pair and booted them out from under a slight overhang. It took me three shots, but I had the satisfaction of seeing them flutter down. We heard John booming away behind us, and when he rejoined us, he was wearing a Chessy cat grin. "Got three", he beamed.

The weather was cause for concern. It was still brutally cold, but now the sky was menacing, for the sun had given up its struggle with the arctic air and was napping under a (Continued on page 56)

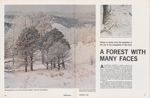

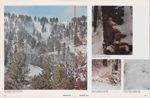

A FOREST WITH MANY FACES

Halsey in winter links the tangibles of the eye to the intangibles of the mind

A NATIONAL FOREST is seldom credited with having a face, let alone having several expressive ones. Yet, the description, "A forest of many faces", is an apt one for Nebraska's National Forest at Halsey. This description is not in the topographical sense, for Halsey's terrain does not resemble common facial features, but rather is an imaginative association, between the scenes found there and the emotions that find expression on the human countenance. These 10 pages of photographs attempt to link the tangibles of the eye with the intangibles of the mind and thus present the forest in a new and highly personalized perspective.

Such association is not farfetched, for the forest is, to some degree, a child of man. Entirely man-planted, Halsey, officially the Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest, is entering its 68th year. It is the culmination of a dream of Dr. Charles Bessey, an eminent botanist of the late 1800's. He and other like-minded

20 NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1969 21

men believed that trees, if once established, could grow in the Sand Hills. Almost a quarter of the forest's 90,350-acre expanse is now covered with trees, mostly evergreens, as a testimony to Dr. Bessey's faith.

A human face is a fickle reflector where expressions come and go with the speed of thought. But, the scenes and situations found in the forest that create the expressions are more lasting, for Halsey is attuned to the slower tempo of nature. The forest is subjected to fewer influences than man, but the forces that do effect it are more elemental and pronounced. Of these, the seasons are perhaps the most powerful, for the forest, unlike man, cannot erect artificial barriers against them. Winter produces the boldest imagery and the strongest association between eye and the resulting emotion.

This link-up between human emotion and forest scene is one of contrasts, for nature is made up of checks and counterchecks, actions and reactions. Each of us

22 NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1969

26

26

sees with a different eye and thinks with a different mind. An individual's responses to the various portrayals of hope and dismay, happiness and sadness, gaiety and melancholy, pleasure and pain found within the forest will be his and his alone. And, that is why a look at the various visages of Halsey can be such a fascinating adventure.

Not everyone can experience the real thing, and for those who can't, NEBRASKAland is pleased to take them on an armchair tour of the wintry woods and supply them with ready-made emotional actions and reactions to the various "faces" of a forest.

No one can look at a seedling, bravely green against the snow, without responding to the hopeful ness of this tiny entity, so resolutely pitting its will to survive against an uncaring and often hostile environment. This contagion of hope is but short-lived, how ever, for when the visitor turns, the fire-blackened corpses of thousands of evergreens, killed in the 1965 fire, confront him. Immediately, the smile of encouragement for the seedling turns to a frown of dismay. The DECEMBER 1969 odds against the little pine, so bravely green against the snow, are just too great.

The visitor trudges over a hill, and a deer, lithe and vibrant, leaps from the shadowed pines. He bounds across the whitened slope with fluid grace, a pleasure to the eyes. His wide-spaced tracks are impressionistic designs in the snow and the watcher bends for a closer look. There, resurrected by the fleeing hooves, are the tatters of what was once a rabbit. The pleasure at see ing the epitome of life turns to pain at witnessing the finality of death.

A family selects a Christmas tree amid a setting straight from Currier and Ives. The gaiety of the young sters sends the spirit soaring, and then, just an eye lift away is jarring contrast. A wind-broken stub, splotchy gray with the pallor of the unburied dead, rises above the green-dotted white. Melancholy conquers gaiety and the faces of observer and observed reflect the sudden change.

The day has warmed and the ice-clad boughs of the Ponderosas sparkle with the false promise of an

27

early spring. Yet, there is something joyous about the scene, and the visitor brightens with the thought. Then comes quick reaction. For deep in the shadows, locked away from the rays of the sun, are other ice-clad boughs, but they are prisoners of another ice, cold, black, and menacing. The viewer scowls; he has been deceived and his expression reflects his dislike of the deception. The promise is there, but the fulfillment is beyond reach.

To roam Halsey in winter is to see a forest of many faces and to know emotions that match them all. The balance between the good and the bad, the gay and the grim, the happy and the sad seems perfect and the observer is neither uplifted nor downcast by the experience. Then comes a great climax.

By now the afternoon is long in the tooth and a softly falling snow adds an eerie luminescence to the aging light. The wanderer tops a sharp rise and there below him sprawls a great part of the forest. Suddenly, he is aware of a cathedral-like silence, a very reverence in the air. He gazes long and as he watches, he feels an inner peace, a sense of tranquillity that is his and his alone.

Finally, he turns away, his face aglow with the grandeur of the scene behind. THE END

FISHING BY BIRD

Challenge is clear — check out "gullability" of Harlan's white bass

JAPANESE FISHERMEN use trained cormorants, streamlined birds with long necks and bills, to catch fish for them. The birds dive into the depths and grab fish in their beaks, then return to the surface where they are relieved of their "take". Nebraska anglers also use birds to catch fish, but in this part of the world it is sea gulls, not cormorants, and they don't have to be trained.

Although the systems differ, the results are comparable, for both birds mean more fish for the anglers. The gulls hunt for gizzard shad, a small, silvery forage fish. White bass also feed on the shad, often pushing large schools of them to the surface. Then the shad are visible to gulls and are caught between the "hammer and the anvil" of birds and bass.

When one gull locates shad, he seemingly gets the word to all others in the area, for soon hundreds of darting, diving, and screaming birds create a frenzy of excitement over a swath several hundred feet wide. This signals the fishermen into action. They watch the gulls and thus locate schools of bass. They then try to capitalize on their feeding spree. Harlan County Reservoir is one of the prime proving grounds for the follow the-gull routine, but most anglers think the peak action comes in late July and August, ending with the first cool breezes about Labor Day.

Sam Hesser, a Lincoln insurance man, has quite a reputation as a white-bass angler. He doesn't buy the theory that white bass stop hitting just because fall is near. What's more, he is always willing to prove his idea to anyone else, so I decided to take him up on it. Sam offered to go to Harlan and take Dick Poe, a Lincoln fireman, with him. So, early on the morning of

For several days we had kept a running check on the gull populations and white-bass success at the lake, and had tried to keep a weather eye open. Weather is important because a slight breeze means slightly rough water at Harlan. A stiff breeze, and a mighty wild time can be had by all. Some telephone calls about a week earlier indicated we had missed the best action and that white-bass success was falling off rapidly. Sam's challenge was clear.

When we arrived at lakeside about 8 a.m., the water was calm and inviting. From one side of the lake to the other, gulls swooped and swam and glided. Everything looked promising, and we were all "raring" to have at it. Within minutes, we backed the boat in, loaded gear, rigged lines, and headed out.

We intended to investigate the lake, watch the gulls and other fishermen for a time, and then catch some fish by relying on the activities of the birds. Our lures were special hand-tied jigs that Dick puts to gether, and all of us were looking forward to a good time while checking out the late-season opportunities. But within minutes, trouble popped up. Dick's out board engine sputtered from the time we got in the water. Though starting O.K., it either died as soon as it was shifted into gear, or barely rattled along.

Hoping it would improve, we took the boat out for a trial run and even fished from it for a while, but it couldn't get us to where the gulls were pointing out the shad. To complicate things, the wind was picking up steadily and the gulls were having their own troubles. The growing turbulence prevented the birds from see ing the schools of shad pushed up by the white bass, so they couldn't pinpoint the fish for us. They were try ing, though.

A couple of times the gulls worked toward us as they followed a few shad that skipped along the surface, but no big schools of white bass were in pursuit only a few scattered fish. In addition to the gulls and the white-bass know-how of Sam and Dick, we had an electronic depth indicator and fish finder on our side. Working on a sonar principle, this rig bounces signals off anything between it and the lake bottom. With some practice, the operator can tell when fish are under the boat. The gadget could tell us the size of the school, and was a double check on the birds' effectiveness.

'When the bass are hitting, you can catch them as fast as you can get them off your hook," Sam offered. "Sometimes you can just about fill up a boat in an hour or so. You know, of course, white bass filets are about as delicious eating as anything you'll find." I admitted they were, and told him he could start showing me how to catch them anytime he was ready. However, the motor was getting steadily worse, so we sputtered back to Patterson Harbor. While Dick towed the vessel to town for repairs, we reloaded our fishing gear into a rental boat.

Braving freshening winds and the increasing waves, Sam and I headed for white-bass territory, which is wherever you find it. As we drifted before the brisk wind in about 15 feet of water, the first bass of the outing grabbed my jig. He was mighty welcome. Within minutes, several of his relatives joined him in the boat as gulls swooped and swung around us. Then, as suddenly as they came, the fish left without leaving any clues to their destination.

Whenever a boat came within hailing distance we asked the anglers about their success. They were not tloing well. Three other Lincolnites, who had spent more than two days at the (Continued on page 5 5)

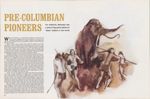

PRE-COLUMBIAN PIONEERS

For millennia, Nebraska was a land of big-game plenty for "Asian" settlers in new world

WHAT A CASUAL, yet momentous occasion it was when the first human stepped within the boundaries of what is now Nebraska and pitted his meager weapons and experience against the powerful bison and speedy antelope he found roaming the lush prairies.

Many winters have passed since that first Indian, his tribal affiliations forever unknown and untraceable and his motives only surmisable, came into this region in the constant search for enough food to keep himself and his family alive. The exact date cannot be ascertained —science can only guess within a few thousand years — when those first Americans crossed the Bering Straits land bridge connecting Asia and the "western" hemisphere. Estimates by an thropologists range from about 15,000 years ago on back.

Perhaps the date is not important except to the historians, but it is natural for people to want to trace their past. Each new archaeological discovery adds to what is known about those people of the past, but it is unlikely that an exact timetable could be established even if remains of the very first man in the new world could be found.

Many things are known about the early plains people, however. Their strength and endurance can only be marveled at. Wherever they traveled, they had to go on foot, carrying everything they owned on their backs or pulled on drags. Food was almost exclusively the large mammals which trod the land — the mammoths and bison — plus some smaller animals to a lesser degree. Supplemental to this, whenever necessary and possible, were berries, seeds, roots, stalks, and leaves depending upon the terrain and season. Certainly, considerable suffering went along with the experiments to determine what was edible and what was not.

There were so few people per square mile back then, and they were kept so busy rounding up enough food to keep them going, there was probably little cause or opportunity for conflict. But, the war of survival was exciting enough and exacted its own toll. A handful of men, even tough and determined hunters, placed every thing on the line when facing a lone mammoth. When confronting a small herd, which was normally the case, the odds against the men climbed out of sight. More often than not, the humans were forced to take advantage of their superior wits and use natural pitfalls.

Remains from several sites indicate the large beasts were some times caught in natural traps, such as bogs, and finished off by man. Such windfalls may or may not have been numerous, and it is possible that those early hunters not only took advantage of existing hazards, but created some of their own. At any rate, they learned that during times of drought, animals from a wide area would travel to the existing water holes. There are also indications that those big-game stalkers were sometimes on hand when ponderous beasts

32

like the mammoth and bison crossed ice-covered streams. If their weight broke the ice, the humans capitalized on the floundering "critters".

Understandably, the coming of winter to the plains was a formidable event for the pedestrian hunters. Probably unaware that warmer climates awaited farther south, the Indians had to make do with what they had by erecting shelters near their food sources. Housing varied by locale and with different peoples, but generally poles suitable for supporting roofs were available in creek bottoms and these were either covered with hides or thatched and piled with dirt. In later times, an igloo-type house evolved, with poles for wall support and rafters, and with a long, covered entrance facing away from the severe winter winds. Usually the low entrances aimed directly east, south, or southwest.

Any discussion of prehistoric or pre-Columbian peoples on the North American continent must necessarily be in generalities. Experts in archaeology and anthropology can only surmise the progression over many centuries by piecing together sketchy evidence collected from widely separated (both in distance and time) sites.

Using the most logical of theories, it appears that after the first arrivals hit this part of the world, a slow dispersion began. It took about 4,000 years, for example, before man inched his way to the southern portions of South America. Probably only about 1,000 years or so were required for them to discover NEBRASKA land, but natural barriers were everywhere. Rivers, large lakes, deserts, mountains, and canyons all posed difficulties for the exploring new arrivals. And, the search for food and water demanded so much of each day's labors that progress was slowed even more.

One band of adventurers might settle down when they found a suitable spot and establish what might be considered a village. Several generations may have passed, then one group or family would move on, looking for richer hunting lands or settling nearer another food source. Even then, in-laws might have been an inducement to move, as well.

Regardless of how it was accomplished or exactly how long it took, man obviously progressed. But, for all their skill and strength, the early plains dwellers 34

When the first agricultural efforts paid off, the die was cast. A revolution occurred in man's life that accelerated his development manyfold. With successful farming, the people had ample food to stave off winter hunger and to supplement game. This, in turn, enabled man to unloose his creative nature. Now, he had time to think and to organize his efforts in all directions, rather than concentrate on survival. The time was well spent. Advancements were made in weapons and hunt ing methods (from the spear to bow and arrow), and the creative and useful art of pottery making came into the picture. Farming also developed rapidly.

Although there may have been no direct correlation, pottery making came into use about the same time as farming, shortly after the beginning of the Christian era. And, this was no small accomplishment, for many scientific and complicated principles are involved. Only certain types of earth were workable, a tempering material had to be included in the formula, moisture was critical at baking time, and baking temperatures had to be high. Of course, not all problems were solved with the initial efforts, but the mere fact that those early people perfected the process is remarkable. Certain tribes or groups found their products improved by adding crushed clam shells. Others used straw, sand, or some gritty material to prevent the clay from sticking to the fingers during the working and to prevent it from cracking during firing.

Tribes on this continent may have discovered pottery at a later date than in the Middle East, but the same set of circumstances could have helped in both cases. The people were known to have lined holes in the ground wTith clay to keep fires contained, and after repeated heating, the clay took on considerable NEBRASKAland strength, so the hole in the ground became a "bowl" in the ground. Noting this, the people probably envisioned a portable pot, and ultimately came up with one to make cooking easier and cleaner. Menus probably improved considerably, too, once pottery came on the scene.

Nebraska, or the land that was to become the state, appealed to both animals of the age and to mankind. It was the northeast boundary of the central plains, with the Niobrara and Missouri rivers serving as border markers. Tremendous herds of buffalo plied the entire plains region at that time and they were most abundant here, so the early hunters found fruitful pickings. For that reason, several sites in Nebraska have been of utmost importance in providing data on those early times. The Lime Creek Site in southwest Nebraska has been scientifically dated by radiocarbon checks of charcoal as nearly 10,000 years old. Three separate locations on the creek yielded flint points mingled with the bones of extinct bison and 16 other mammals, as well as birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Many of the weapons were made of jasper, which could have originated at various places along the Republican Valley.

A few hundred miles to the northeast, in Burt County, is the Logan Creek Site. Four of the five occupation levels at this find date to pre-pottery times. The second level from the top is radiocarbon dated at 4,674 B.C., while the lowest level extends back 7,250 years from today.

The Red Smoke and Allen sites near Lime Creek in Frontier County, show they were used as permanent camps as well as short-term bases. Radiocarbon dates of charcoal from several levels in the Allen Site range from about 8,000 years to 10,500 years ago. Bones of the extinct Bison occidentalis, found in the uppermost level of a site near Grand Island, tested 8,862 years old. A list of other NEBRASKAland diggings which have provided valuable information and artifacts would read like a Who's Who directory. There are the Leary, Sterns Creek, Redbird, St. Helena, Ash Hollow, Sweet water, and hundreds more, each representing an im portant segment of man's early development.

For many centuries life went on for the Nebraska plains people with only some occasional difficulty and DECEMBER 1969 hardship. Gradually, however, as populations grew so did competition. Some groups or tribes accumulated material wealth in the form of stored food, tools, and weapons which made them likely targets for raids by other peoples. The taking of slaves during raids also became common practice, which was responsible for more animosity than the theft of grain or beans. Several cultures, including some from Nebraska, there fore established fortifications around their villages. Trenches backed up by walls served in most cases, although the very large settlements usually found such precautions unnecessary.

Eventually the early cultures disappeared, either being wiped out or assimilated by others. Although there are no clear-cut, progressive stages through which the various peoples can be traced, there are some definite points upon which to hang identification. The earliest arrivals on the continent, logically called the early big-game hunters, probably evolved into different groups by cultural and climatic influences over a good number of years. Also, migration into the continent from Asia could have continued over a long period and might have included people from several ethnic backgrounds.

Definite characteristics in craftsmanship and design of flint points show distinct variances in tribal handiwork. These have been widely accepted as a means to distinguish and classify people, and, to a less er extent, establish approximate time of use. Thus, the Clovis point denotes the oldest hunters yet recognized, followed by the Folsom and Plainview. All these were prevalent during the period of the big-game hunters, from about 10,000 to 5,000 B.C. The Lime Creek sites of southwest Nebraska date to this time, and all three types of points have been uncovered here at one site or another.

A considerable period followed when few changes in methods occurred until about 5,000 B.C. when Bison occidentalis finally became extinct and the modern bison was left to rule the plains grasslands. At roughly that time, people identified as butte dwellers were known to have lived in western Nebraska. Several occupation levels atop Signal Butte are about 3,500 years old and show (Continued on page 55)

A LAKE IS BORN

Fantasies are written by man, but nature wrote one near Oakdale on the day the earth fell

FANTASIES ARE not all written by man. Nature wrote one in Antelope County, 4 1/2 miles southwest of Oakdale, Nebraska, when a pair of springs gave birth to a natural lake. The Oakdale happening has kept people guessing and talking for more than 40 years.

The blessed event of April 1927 was sensational. It caused plenty of commotion and more excitement, and attracted thousands of visitors from Nebraska and adjoining states. The astonishing thing about it was the alteration in the land. Several acres dropped 40 to 100 feet from a hilltop to the bottom of a ravine. Neighbors who had driven their cattle across that hill stared in amazement at the fallen pasture.

Though all who came to look upon the phenomenon were equally awestricken, there was much controversy as to the why, when, and how of its happening. Every spoken and written report on the sink differs from every other. At the time arguments raged throughout the countryside about the whole matter, and nearly every farmer had his own opinion.

On a Saturday night at the Springer Grocery in Oakdale in 1927, the talk might have run like this:

"I heard Austin El wood lost a team of mules." Farmer Johnson said to Farmer Carlson.

"Ornery critters run away?"

"No, they just dropped down."

"Down where?"

"Nobody knows. It is like that city in the Bible where the earth opened up and swallowed the people."

"How could that happen here? What kind of tall tale is this?"

"It is not a tall tale, nor a joke. There is a sinkhole on Elwood's farm; the whole pasture, trees and all, dropped about 40 feet."

"Does anybody know what caused it?"

"Some say the heavy rains of last fall set it going, but I know there have been two springs down on that hillside emptying away silt and lime for years. No doubt they made a big, hollow cavern under the hill so that when the rains came, the clay above just sank down all at once."

"Not all at once." Farmer Swanson, coming into the store, joined in the conversation. "It started last fall, in November. I remember it well because the first we heard about the caving was on the day Aunt Minnie died. Then on Sunday, on the way home from the funeral, we drove over there. It was just a little place then. It was not until after the spring thaw that it began to really move."

"It's been down for weeks," the grocer spoke up. "My boys have been going over with school classes every week for two months. They are interested in seeing how much more it has sunk from week to week."

"They can talk about the heavy rains all they want to," Swanson said, "but I think the beavers that were always working in (Continued on page 52)

Points for Ducks

Hunters who meet responsibilities of scorecard season may help revolutionize waterfowl hunting

NEBRASKA DUCK hunters who can meet challenge and responsibilities of the 1969-70 High Plains Experimental Point System Season will make a great contribution to a program that can revolutionize future waterfowl hunting. This experimental season will, for the first time in years, let the hunter in Nebraska bag a maximum of four mallards a day. Such shooting is limited to west of U.S. Highway 83, and every hunter, regardless of age, must have a special, free permit. Hunters, 16 or over, must also have a Nebraska hunting license and a federal duck stamp. Applications for these permits are available from permit vendors and Nebraska Game and Parks Commission offices.

This special season, beginning December 13,1969, and running through January 4, 1970, utilizes a point system. It works like this: Hunters have 40-plus points when they start their day. Mallard drakes are worth 10 points apiece. All other ducks, including mallard hens, coots, and mergansers are 40-point birds. A bag limit is reached when a hunter, equals or exceeds 40 points with his last duck. For example, if a hunter shoots any 40-point bird before he shoots a greenhead, he has filled his daily bag and must quit. It is ILLEGAL to shoot any more ducks after the 40-point limit is reached.

This season will be a real test of the waterfowler's willingness and ability to do selective shooting. A hunter, well versed in duck identification, can take four greenhead drakes. A less discriminating water fowler will have to hang up his gun for the day when he kills any duck other than a drake mallard.

A random sample of hunters will be sent envelopes asking for wings to determine the age ratios of the birds they shoot during the High Plains season. Some will also receive a questionnaire after the season, ask ing how many ducks they took, days hunted, and their reactions to the experimental season. The return of this information is vital in determining the success of the season and will influence the setting of similar ones in the future.

This experiment is part of a new concept in species management, a term often heard by waterfowlers, but perhaps not fully understood. Species management is simply directing shooting pressure toward or away from individual duck species. When the birds need additional protection, restrictions are applied. When ducks can stand harvesting, liberalizations are made.

Species management in past years has depended upon a shooter's ability to correctly identify ducks BEFORE they are shot. Past experience with special teal seasons has shown the hunters' ability to do so often leaves much to be desired. The point system in species management requires a gunner to identify what he has shot AFTER (Continued on page 51)

Pintail: Drake identifiable by elongated, spike-like tail and long, pointed wings. Whitish on breast and belly, mottled gray on back. Hens lack distinctive "spike" tail and are darker in overall appearance. Very swift on the wing, pintails come in high and descend in a zigzag spiral. Decoys have to be right to lure them down. Abundant statewide, the duck is fine eating. Weights range from 1 to 2% pounds, but a long wingspread makes duck look bigger. Colloquial names are "spiketail", "sprig", and "pinnie". The drake utters a sharp "qua, qua" in flight, while the female has an occasional hoarse "quack". Hardy birds, some pintails stay here all winter. Slim silhouette, pointed tail, flight characteristics, and wingbeat are field identifiers.

Gadwall: Drake is identifiable by black and white speculum and gray appearance. The hens are mottled brown with whitish breasts and the same specula as drakes. Females lack chestnut wing patches of the males. A native nester, as well as a migrant, it is well-known in Nebraska. Gadwalls fly in small, compact flocks and have a rapid wingbeat. Their flight pattern is usually direct and they decoy easily. They will associate with baldpates and pintails. The table quality of gadwalls is a matter of opinion. Some like them, others don't. Medium size ducks, they run from IV2 to 2 pounds. Drakes have three calls, a sharp "kack-kack", a reed-like, "whack", and a shrill whistle. Hens have a higher pitched and a softer "quack" than mallards. White speculum and size are practical field identifiers.

Mallard: Drake is easiest of all ducks to identify and is No. 1 with most waterfowlers. Green head, white ring on neck, rich chestnut breast, grayish belly, and orange feet are trademarks. Hen is drabber, running to overall brown, except for purple-blue speculum edged in white. Flocks are often huge and late-season birds are usually leery of decoys unless the blocks are in perfect array. Mallards will respond to calls. Abundant statewide, this duck is great eating. They weigh from 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 pounds. The size and slow wingbeat make them deceptive targets. Mallards can do 45 to 60 miles per hour, but they seem much slower in the air. The hen has a loud, "quack", the male, a low, reedy "quack". Drake's distinctive colors and large size are field identifiers.

Green-winged teal: Smallest of all puddle ducks, their size is clue to identification. Drake has a crested red head, marked with glossy green eye patches. His overall appearance runs to gray. Hen lacks crest and patch and has a mottled-brown appearance. Both sexes have green specula. Green-winged teal are fast and erratic flyers and often resemble a flock of pigeons in flight. They decoy easily. Weights run from 10 to 14 ounces, and birds are considered prime eat ing. Very hardy, green-winged teal winter in Nebraska, and frequent smaller ponds, puddles, and creeks more than big waters. Distribution is statewide. Drakes have calls ranging from a twit ter to sharp whistle. Hens have a soft "quack" Birds coming in low, sound a distinct "whoosh" as they pass. Size and flight are field identifiers.

40 NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1969 41

American goldeneye: Identifiable in flight by sharp wing whistle. Male has big, green head with a white spot just below the eye. Hen has large, chestnutty head and looks smaller than male. Birds are extremely swift flyers. They fly in small flocks and circle to gain altitude. American goldeneyes do not decoy well. Medium-size ducks, they weigh from 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 pounds and are considered as average table birds. Uncommon visitors to Nebraska, they can be found on the larger western reservoirs. A common name is whistler. American goldeneyes are usually rather quiet, but the drake does utter a sharp, "speer, speer", while the female has a low-pitched "quack". Size, color, blocky silhouette, and wing whistle are identifiers.

Bufflehead: Small'duck identifiable by big head and short neck. Drakes have white wing patches. Females are quite drab with white specula and whitish underparts. Buffleheads usually fly in small flocks close to the water. Their wingbeats are rapid and they alight with a splash and slide to a stop. Unlike many divers, buffleheads lift almost straight up. They decoy easily, coming in without much hesitation. These ducks are "fish eaters" and not good table fare. The average weight is between one-half and 1 1/2 pounds. The buffleheads are common migrants in Nebraska and are usually seen on the larger western lakes. These little ducks are also called "butter ducks" or "dippers". Size, color, and flight styles are best field identifiers.

Common merganser: Identifiable in flight by the rakish shape. Flying drake shows more white on body, wings than any other duck. A green head, large size, and a long, red bill also help in identification. The hen has a brown head, grayish back, and whitish breast. Flight is swift and direct in a line formation with bill, head, and body held on the horizon tal. The common mergansers are large ducks and weigh from 3 to 4x1/2 pounds. Condemned as "fish ducks", mergansers are usually passed up by waterfowlers because of their strong fishy flavor. The birds are unusually silent, but will let loose with a hoarse croak when startled. They are well known and widely distributed throughout Nebraska. Size and silhouette are field identifiers.

Red-breasted merganser: Drake's markings resemble those of male mallard. Contoured silhouette, double crests, and long narrow head are distinctive features. Female has crests like the drake, but head is dark, paling to white under the chin. Their flight style is similar to that of common merganser. They prefer salt water, and are rare migrants to Nebraska. Weights run from 2 to 2 1/2 pounds. Birds are not tasty because of their fish eating. Divers, the red breasted mergansers are interesting ducks to watch. Their dives for fish are likened to an ar row's thrust. Two of the colloquial names are "fish duck" and "sawbill". Red-breasted mergansers are normally silent, but they can utter a hoarse croak. Size and silhouette aid in identification.

Holiday Favorites

This Christmas menu blends Nebraska's age-old tradition and rich Old World heritage

THE HOLIDAY season rapidly approaches, NEBRASKAland chefs across the state will be preparing the many traditional favorites that annually delight their families. From roasted chestnuts to Czech houska to New Year's eggnog, the holiday menu adds a dash of color and flavor that can be found at no other time of the year.

Each nationality has its own traditions, and all have some customs in common. All over Nebraska, people sit down on Christmas Day to a feast that features roast fowl. There's cranberry sauce, stuffing for the bird, special breads and pastries, and pies.

The following is a holiday menu that combines the predominent national and traditional influences:

Roasted Chestnuts or Pickled Pike Cranberry Orange Salad Goose with Orange Stuffing Brunkal—(Brown Cabbage) Harvard Beets Houska or Stollen Wine or Hot Tea with Lemon Plum Pudding Mince Pie ROASTED CHESTNUTS

ROASTED CHESTNUTS

"Chestnuts roasting on an open fire..." That's the way one popular holiday song begins, and it brings up an old custom — roasted chestnuts. Wash chestnuts and cut a 'gash in each one well through its outer layer. Place them in a heavy pan and add a teaspoon of cooking oil per cup of nuts. Set the pan in a hot oven (400 to 450°) and stir several times while baking. After 20 minutes of baking,

Another old favorite is cranberry sauce. A modern variation on that theme is the following, using today's gelatin dessert:

2 cups ground 1/2-cup chopped nuts cranberries 1 cup chopped celery 2 cups ground apple 1 orange with rind- wedges with peels grated 1 package raspberry jelloDissolve jello in 1 cup hot water. Add 1 cup cold water and all other

ROAST GOOSENebraska's Irish are among those who find delight in the old-fashion Christmas goose, and this orange stuffing adds even more appeal to the old custom.

Scrub the goose with hot water and baking-soda solution. Rinse in clear, cold water and dry. Stuff with orange stuffing, truss, salt and pep- per, and puncture the fat so that it can drain out. Place the goose on a rack in a roaster and roast 20 min- utes per pound. Baste frequently with drippings in the pan. Pour off the fat occasionally. For a wild goose of dubious age, pour one cup of water into the pan and cover for the last hour of cooking.

ORANGE STUFFING 1/3-cup butter, margarine, or poulty fat 2 tablespoons chopped onion 1/2-teaspoon savory 1/2 to 3/4-teaspoon salt seasoning 1 cup orange wedges Pepper to taste 1 quart bread crumbsMelt the fat in fry pan, add onion, and cook a few minutes. Add to crumbs with the seasonings and

Stir in the eggs, shortening, fruits, and nuts. Add more flour a little at a time, working it in with your hand or a spoon until the dough cleans the sides of the bowl. Turn it out onto a lightly-floured, cloth-covered board. Knead until all sides are greased. Cover and let it rise in a warm place until doubled — about 1 hour. Dent remains when the finger is pressed deep into the side of the dough. Punch dough down. Shape into one large or two smaller Stollen. Place on a greased baking sheet. Let rise until a dent remains when finger is pressed lightly on side of dough — about 30 minutes. Preheat oven to moderate (350°). Bake about 30 minutes, or until well browned. Cool on a rack.

To Shape Stollen: Pat out dough into an oval, pressing out bubbles. Spread oval with soft butter. Fold in two the long way and

A. B. (Pinnacle Jake) Snyder, the Nebraska cowboy made famous by Nellie Yost's book, Pinnacle Jake, was very fond of "son-of-a-gun-in-a- sack". It was a suet pudding, steamed in a sack over a roundup campfire. Mrs. Snyder had never heard of it, but Jake had a pretty good idea of what, though not how much of what, went into the pudding. So his wife tried mixing and steaming a batch. Jake tested and criticized. After several tries, she got the right "scald" on the mix and the pudding tasted just as good as the ones the chuckwagon cooks used to make.

This suet pudding, better known today as English plum pudding, was

Cook slowly until slightly thick and add your favorite flavoring.

Christmas wine hearkens back to Christian beliefs of many centuries ago. Hot tea can substitute for those who prefer a strictly non-alcoholic beverage.

remove the pan and let the chestnuts cool. Remove the shells and skins with a knife.

PICKLED PIKEFor the avid sportsman, now is the time to drag that northern pike out of the freezer and put it to taste- tingling use. As a pickled appetizer it can't oe beat.

Sauce 2 cups olive oil A few bay leaves 1 cup vinegar 2 large, sliced onions 10 peppercorns 1/2-teaspoon salt Fish 3 pounds pike, cut in1-inch pieces 1/4-cup flour 1 cup olive oil Juice of 1 large lime 2 large cloves garlic, 4 1/2 teaspoons salt peeled and crushedMix the sauce ingredients in a large kettle and cook slowly for 1 hour and cool. Rinse fish in running water and dry. Sprinkle lime juice over the fish slices and season with salt. Flour both sides of the slices lightly when ready to fry. In a frying pan, heat olive oil with crushed garlic cloves. Remove garlic as soon as it is brown. Add as many fish slices as will fit in the pan and brown over moderate heat on both sides. Lower heat and cook the slices for 15 minutes.

Fry the remaining slices in same way. Remove and arrange in a deep, glass dish as follows: Pour a little cool sauce over a few fish slices in 46 ingredients. Pour in molds and chill. Serve on lettuce leaves.

BRUNKALThe Swedish serve Brunkal as a Christmas Day delight. Translated brown cabbage, this dish is a tasty addition to any Yuletime feast.

2 white cabbages, cut 1 tablespoon sugar or in small pieces syrup 3 to 4 tablespoons 1 to 2 tablespoons shortening vinegar 1 peeled, diced appleMelt shortening in large pan and add the cabbage, sugar, and apple. Simmer 1/2-hour. Add vinegar and continue simmering, stirring occasionally, until all cabbage is brown. Add more vinegar or sugar to taste. Serves 8.

The holiday season is, of course, a time when fresh fruits and vegetables are out of season, so grandma used to improvise with her delicious canned, pickled, and dried substitutes—until modern transportation and technology could bring those fresh fruits to the December table. A popular favorite of old was pickled beets—Harvard beets—and their brillant color, along with the greens of dill and sweet-cucumber pickles, adds cheer to the Christmas meal. orange slices. Mix lightly but well. Stuff goose loosely.

STOLLENGerman and Czech children look forward excitedly to the holiday breads. Both nationalities enjoy special fruit breads in this the jolliest of times. The German Stollen and the Czech Houska are traditions of centuries, observed faithfully as they were in the old countries.

1 teaspoon salt 1/2-cup soft shortening 1/3-cup sugar 1/2-cup cut-up 1/2-cup scalded milk candied cherries 1/2-cup warm water 2 eggs 2 packages active 1/2-cup finely cut dry yeast citron 4 1/2 to 4 3/4 cups sifted 1/2-cup raisins all-purpose flour 1/2-cup cut-up nutsMeasure salt and sugar into a large mixing bowl. Pour in the scalded milk and let it cool to lukewarm. Meanwhile sprinkle the yeast over the warm water in a cup or small bowl and let it stand 3 to 5 minutes. Stir to dissolve. Blend the milk mixture with a rubber spatula until sugar and salt are dissolved. Add NEBRASKAland curve into a crescent. Press folded edge firmly so Stollen will not open.

HOUSKA 2 packages dry yeast 1 tablespoon salt 1/4-cup water 1 cup raisins 3 cups milk 1/2-cup almonds, 3/4-cup sugar blanched and 1 cup cream chopped About 8 cups flourDissolve yeast in 1/4-cup water. Scald milk and cool. Mix yeast, water, and milk, and add enough flour to make a sponge. Let rise. Add cream, sugar, salt, and enough flour to make a soft dough. Place in a greased bowl and let rise until double in size. Punch dough down; add raisins and al- monds. Let rise again until double. a variation of the old holiday dessert — plum pudding without any plums.

1 cup chopped raisins 1 teaspoon soda in 2 1 cup chopped or tablespoons hot ground suet water 1 cup currants 1 egg 1/2-cup sorghum or 1/2-cup milk New Orleans molassesMix all ingredients, adding enough flour to make a soft batter. Add spices (nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves, allspice) to suit your taste. Put batter into steamer and steam 2 1/2 to 3 hours. Chopped citron may be added. This recipe seemed to vary according to the ingredients at hand, and the individual's taste.

DECEMBER 1969 MINCEMEAT**Another Christmas must are the mince pies, and May Trego made some of the best. In the old days, the Trego Ranch in Cottonwood Valley was located on a main road between Sutherland and the ranches in what was then called the "North Country". May, a Nebraska rancher's wife, was famous over several counties for her top-notch cooking. Her mince pies were right at the top of the list. (Venison is a delicious substitute for the beef).

4 pounds lean boiled 2 teaspoons nutmeg beef, chopped fine 1 pound brown sugar 8 pounds tart apples, 1 quart molasses chopped 2 quarts sweet cider 1 pound chopped suet 1 teaspoon each of 3 pounds seeded salt, pepper, mace, raisins allspice, & cloves 2 pounds currants 4 teaspoons 1/2-pound citron, cut cinnamon fineHeat thoroughly, mix well, cool, and stir in 1 pint good brandy and 1 pint Madeira wine. Put in crock, cover tightly, and set in cold place. It will keep all winter. Make pie crust as usual and fill with mincemeat. Add apple juice if mincemeat seems too dry.

The entire holiday season is a gour met's delight. Besides the fascinat ing menus (Continued on page 55)

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . FATHEAD MINNOW

A favorite with anglers and game fish, this species is good bait and dependable food source for predators

BEING CALLED a fathead marks one as foolish, but the term, fathead, is also descriptive of a male minnow with the scientific identification of Pimephales promelas. This minnow develops a thickened back and head during the spawning season to earn his common name. A member of the largest group of freshwater fish, the minnows, the fathead is perhaps best known as a bait fish. Minnow fishermen consider them one of the best, for they stay alive and active on the hook for an hour or more. Crappie anglers prefer the smaller minnows, while bass men trust their luck to full-grown fatheads. Due to wide distribution, durability, and ease of rearing, fatheads are a favorite among private fish culturists.

Nebraska bait vendors import a lot of fat-headed minnows from other states as well as obtaining them from "local" sources. There are no restrictions on their use as bait in this state except in waters where the use of all minnows as bait is prohibited. These restricted areas are listed in the NEBRASKAland Fishing Guide. Vendors must have a bait-vendor's permit to retail fat heads and commercial transporter must have a fish dealer's license. Nebraska anglers are restricted to a possession maximum of 100 minnows of any one or combined species at any given time.

This species is one of approximately 40 minnows found in Nebraska waters. They seem to be in all stream systems, many ponds, and exist abundantly in many Sand Hills lakes. Geographically, the fathead is common throughout southern Canada and in the northern United States from east of the Rocky Mountains to Maine and southward to the Susquehanna River and the gulf states.

Fatheads can be recognized by their robust bodies, short, rounded heads, and blunt snouts. Their mouths are small and slightly upturned. Coloration is usually dark, brown to olivaceous dorsally, with adults having a copper or brass tinge. Younger fish may be a yellow silver on the back. The underside is usually a whitish yellow or silvery. There is a dusky crossbar on the dorsal fin. Breeding males become quite dark with tubercles or horn-like projections aligned in three rows across the snout and a few on the chin. These are DECEMBER 1969 lacking on females and disappear from males after the breeding season.

Spawning usually starts the third week in May when water temperatures reach 58 to 65° and continues until August. It has been noted that when water temperatures climb to more than 85° spawning ceases. A single female lays from 200 to 500 eggs which are adhesive and cling to the underside of underwater objects. In many Sand Hills lakes eggs have been found on fence posts, barbed wire, and stems of hardstem bulrush. A male guards the nesting area where more than one female may spawn. Hatching depends on water temperature but will occur in five to six days. The fatheads take the future of their species seriously and spawn repeatedly during the year. Some young that hatch early may spawn before autumn cools the water below the acceptable temperatures.

The life span of hatchery-reared fatheads is 12 to 15 months. Mature fish will range in size from 1 1/2 to 4 inches with the male larger than the female. A large percentage will die in 30 to 60 days following spawn ing. Individuals reach 2 to 2 1/2 inches in about 120 days under hatchery conditions.

The food of the fathead consists of many kinds of microscopic plants and animals. Apparently, the fathead has no preference but they rarely eat fish, hence they are frequently stocked in largemouth bass nursery ponds to furnish food. The Fisheries Division of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission often recommends the introduction of fat-headed minnows in farm ponds as forage for bass and catfish.

The fat-headed minnow occupies a particularly unique role in the Sand Hills as he is often found in lakes too alkaline for many game fish. This fits in the pattern as natural populations seem to flourish in the absence of competition.

The nature of the fat-headed minnow suggests that he will survive in our changing environment. Being tolerant of pollution, flooding, and low flows coupled with a prolonged breeding season and rapid maturity, it seems they will remain on the scene for a long time, proving that "fatheads" aren't so dumb after all. THE END

POINTS FOR DUCKS

(Continued from page 39)he's shot it without penalizing him for an honest mistake.

Besides allowing for an error, the point system has a built-in incentive for waterfowlers to learn duck identification "on the wing". It is possible that in future regular duck seasons, a point differential between a gadwall, for example, and a hen mallard may result in a bigger daily limit. Just as the keen-eyed and discriminant shooter will have a bigger daily limit than the "hen shooter" during this experimental season, hunters in the future who excel in identification may take bigger daily bags if they shoot only low-point ducks. A study of the color illustrations on pages 40 to 43 can help hunters in their species identification.

Surveys in some Central Fly way states show there is an apparent excess of mallard drakes. During the past 4 winters, Nebraska biologists have banded over 16,000 mallards and made numerous sex-ratio counts on the state's wintering mallards. These studies show about 1.9 drakes per hen in western Nebraska and a relatively high survival rate for greenheads, compared to other mallard wintering populations throughout the country.

The results of the High Plains Experimental Point System Season will play a big part in determining whether or not this type of regulation is a practical way to better utilize the various species of wild ducks. Much depends on hunter behavior. It is hoped that Nebraska sportsmen will be men enough to abide by the law, and end their day's hunt when a 40-point duck is taken. It is very important, also, that the entire bag consists of mallard drakes, for the need to protect the hen mallard was never greater than today. Participants in this experimental season are urged to maintain their vigilance and not lower their standards for that last bird. No one has more at stake in this experimental season than the duck hunter himself. Hopefully, he will accept its responsibility and challenge. THE END

COUNTRY KIND OF WINTER

(Continued from page 14)the hills in a whipped-cream fairyland, as the lights of the schoolhouse beckon us hurry. On such a night we are quite willing to believe along with our five year-old that Santa will indeed be there to assure us of his annual visit.

But winter is not always a cold tranquillity in the ranch country, for this is a season of devastating blizzards. Great terrors of snow and wind howl down from the north, making all outdoors a risk for humans and a peril for livestock. We are glad, when in the ominous calm that presages a storm, the calves follow the feed truck into shelter and bed down on the hay spread before them. The horses, too, know that an ordeal is in the offing, and so they drift toward the barn on their own, their backs hunched, their tails tucked under, and their hair matted DECEMBER 1969 with ice. They trudge into the corrals and drink deep from the stock tank.

Our concern for the animals, lessened by the knowledge they are secure, gives way to anticipation of an evening within the comfort of our home. There is no television, but there is lots of reading to fill the void. We sing to the accompaniment of a beat-up guitar, or pursue a hobby that satisfies the need to be doing some thing with our hands. We savor these moments, knowing that soon they must give way to bedtime for ranch chores begin with the dawn.

Even our little one accepts the inevitable without complaint. She is tired from a day of "helping Daddy". A day of faithfully following his far-apart steps across the snow, making snow angels, or sitting with her face snuggled against the warm flank of a benevolent milk cow, determinedly trying to make the milk enter the bucket in swinging spurts in stead of soundless dribbles.

When the blizzard has blown itself out, what fun it is to hike down to the pond amid the sun-bright splendor of the afternoon. We hold our skates in one hand and pull the "snow boat" with the other. The ice is at least a foot thick and wonder of wonders, it is clean swept by the forceful wind. But even if it wasn't, we would shovel off a room-size spot on which to skate.

It is an effort to skate against the gale, but we do it, encouraged by the anticipation of an almost effortless glide back, almost leaning on the wind. The kids take turns with the snow boat as we spin it around and around and then thrust it away on a fast ride down the ice to a chorus of a puppy's wild barks and the squealing laughter of the young ones.

We stay until the sun courts the western horizon and then walk back, caught in the enchantment of a breathtaking sunset. A little wood is on our way and we enter, stepping high to avoid the mounded snares of fallen logs or toe catching branches. We study the delicate tracery of mice tracks and watch for the pheasants that winter there.