NEBRASKAland AFIELD

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS For Free Distribution Pubiished by Nebraska Game and Parks Commission HUNTING BONUS WHERE TO HUNT, STAY, AND EAT GUIDES PROCESSORS FIELD TIPS GAME RECIPES AFRICAN HUNTER TRIES RINGNECKS NEW-HUNTING GROUSE WITH DECOYS

OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland of the Air

FROM WINE TO ONIONS

AS NEBRASKA prepares to uphold its title of Mixed-Bag Capital, sportsmen and their wives are faced with a problem as old as hunting — how to prepare the game. Recipes number in the thousands and include everything from rare wines to common onions in their ingredients, but here are a few recipes which may tickle the imagination as well as the palate of any game chef.

Nebraska's First Lady, Mrs. Norbert Tiemann, recommends this method for preparing that wily bird, the pheasant:

Cut pheasant across the grain into bite-size pieces. Dip each piece into mixture of beaten egg and milk and then into finely crushed cracker crumbs. Fry in butter or margarine until tender and well browned.

Mrs. Howard Wolff, wife of the Omaha World-Herald outdoor writer, prepares quail this way:

Fry quail in grease until they are a delicate golden color. Chop bacon, mushrooms, and vegetables until fine. Mix together and simmer until the mixture sweats — the onion will become almost transparent.

Wash the rice four or five times in hot water. Boil until it fluffs, drain and mix with vegetables. Stuff quail with rice, wrap them individually in foil, and bake in a 300° oven for I 1/2 hours. Serves four.

Mrs. Ernie Dusek, wife of Nebraska's well-known wrestling promoter, prepares rabbit and raccoon with gravy from this recipe:

Raccoon (or rabbit) With Gravy 4 pieces of bacon 1 onion 1 cleaned and cut up coon (or two rabbits) Salt 1/2-cup vinegar 1 large can evaporated milk Flour Water Red pepperChop bacon and onion, then combine the two in a heavy pan and saute. Add raccoon or rabbit, vinegar (for coon only), and salt and pepper to taste. Cover and simmer until tender, adding water if necessary to keep the meat moist. Add milk thickened with flour for gravy. Serves four.

Reinholt Rebensdorf, chef at the Hotel Cornhusker, in Lincoln, recommends this recipe for lovers of fried squirrel:

Fried Squirrel 2 oz. sherry wine Flour 1 squirrel 4 oz. sour cream 4 oz. mushroomsRoll squirrel in flour and pan fry. Make natural gravy from drippings, remove from heat and add sour cream, mushrooms, and wine. Serve squirrel in gravy. Serves two.

Mrs. Rex Stotts, wife of a former member of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, uses this recipe for making tough grouse tender:

Baked Grouse Grouse cut in Cooking fat serving pieces Cream or half and Flour half Salt and pepper to taste Roll pieces in seasoned flour. Brown slowly in hot fat turning once. Place browned pieces in baking dish or small roaster. Add cream to partially cover and place lid on roaster. Bake in 325° oven until tender —about I 1/2 to 2 hours. Gravy may be made from the drippings or mushroom soup may be substituted for it. Three grouse make six servings. Arthur C. Storz of Storz Brewery in Omaha likes his venison prepared this way:

Venison steak, panbroiled and served rare with Sauce Poivrade. Soaking venison steaks in a marinade makes them more tender and adds a delightful flavor. Ingredients in this marinade include white wine, vinegar, olive oil, bay leaves, and shallots. The meat is marinated for one day.

4 venison round 2 bay leaves steaks, 8 to 9 1/8-teaspoon pepper ounces each, cut Small pinch cloves 1/2 to 3/4-inch thick 2 cups dry 2 shallots, chopped white wine 2 carrots, sliced 1 cup mild vinegar 2 onions, sliced (3/4-cup cider vinegar of 5 percent acidity mixed with 1/4-cup water) 1 clove garlic, chopped 1/8-teaspoon thyme 1/2-cup olive oilPlace steaks in an enamel, glass, or earthenware bowl. Add remaining ingredients. Let stand in refrigerator 24 hours. Turn meat several times in marinade. Remove steak. Dry. Reserve marinade. Saute steaks in shallow hot fat until brown on both sides. Do not 4 NEBRASKAland AFIELD overcook; steaks should be rare. Serve on a hot platter with Sauce Poivrade. Yields four servings. If desired, four venison sirloin steaks about 7 ounces each and cut 1/2 to 3/4-inches thick, may be substituted. Also, small, white onions may be substituted for the shallots.

Sauce PoivradeSauce Poivrade or pepper sauce accents the deliciousness of venison steaks. It is used in fine French kitchens.

1/2-cup chopped carrots 1/2-cup chopped onions 1 small clove garlic 1 sprig parsley 1 bay leaf 2 tablespoons olive oil 1/4-cup tarragon or cider vinegar Salt 1 1/2 cups brown sauce(canned meat gravy or sauce made from a venison-bone stock) 6 peppercorns, crushed 1/4-teaspoon or less thyme 1/4-cup red currant jellyBrown carrots, onions, garlic, parsley, and bay leaf in olive oil, stirring often. Drain off any excess oil. Add vinegar and marinade. Boil till mixture is reduced about one-third. Add brown sauce and cook, stirring often, about 20 minutes. Add peppercorns, thyme, and salt to taste. Simmer about 10 minutes longer. Strain through a very fine sieve or several thicknesses of cheesecloth. Skim fat from surface if necessary. Before serving, reheat and blend in jelly. Yields 2 1/2 cups.

Mrs. Elmer Ourecky, co-editor of the Czech cookbook, Favorite Recipes of the Nebraska Czechs, endorses this recipe for NEBRASKAland duck.

Clean the duck; soak in cold water for one-half hour. Interlard duck with bacon strips. Place duck, ham, vegetables, and seasonings in heavy saucepan, add one-quarter cup water and stew slowly. Baste occasionally.

Prepare sauce of fresh mushrooms, add strained liquid, pour over duck, and let stand in hot place for 15 minutes. Sauce may be made of strained liquid, thickened with flour and butter browned together and then thinned to proper consistency. Serves two.

These are just a sampling of the many recipes for preparing NEBRASKAland game. Dozens of others are available in various cookbooks. But try some of these and you'll agree that a game dinner is a fitting climax to a successful day afield.

THE END

DEER ATTACK

by Robert Webb as told to NEBRASKAlandANYTIME A HUNTER downs a five - point white - tailed buck that is usually reason enough to have the head mounted. But I had my trophy mounted for two reasons: first, because the typical "whitetail" rack is a real beauty, and second, be cause that deer taught me a valuable outdoor lesson. When the head is finally on the wall, a pair of tattered pants will be hanging next to it, for on November 9, 1968 that big Boone County buck almost bagged me in stead of the other way around.

My first encounter with the buck was on a preseason scouting expedition with my hunting partner, Darrell Meyer of Albion. The two of us were looking over several areas in the Calamus deer hunting unit when we spotted two bucks near a grove of trees just west of Akron. I didn't know it then, but the biggest one would make me the hunted instead of the hunter. Plenty of deer sign in the timber and occasional glimpses of several other bucks spurred us to construct two tree stands 200 yards apart in the grove.

The night before the opening of the deer season we drove from our homes in Albion to a predetermined campsite near our stands. Still hunting from a tree stand can be a cold and miserable way to pass the early morning hours if you are not proper ly clothed. After a temperature read ing in the morning, I slipped a pair of Air Force flight pants over my regular clothing, and in the 5:30 a.m. dark, we climbed into our tree stands.

In the cloudy gray just preceding dawn, I spotted 12 does in a patch of pine trees just northwest of my stand. Carefully I scanned the bedded-down deer for a buck, and as I watched the herd, I heard a snap of twigs behind me. Slowly I turned around and watched a doe and fawn walk directly beneath me. The doe and fawn hadn't spotted me and neither had the herd, and that is the way I wanted it. The deer were my decoys, for I was sure they would draw a buck into the clearing. Be sides that, watching the whitetails made the time go faster and I for got about the cold.

As I watched the deer, I had almost forgotten why I was perched up in that uncomfortable tree like a 165 pound bird. But a rustle of leaves brought an end to my musing and made me turn to my right. There, emerging from a stand of timber just 60 yards away, was my reason for sitting in the tree. A white-tailed buck, looking as big as an elk, cautiously made his way into a small clearing. When he was sure he was safe, the deer slowly walked toward the herd, pausing now and then to crop a mouthful of grass. I drew a deep breath and slowly raised my .300 magnum.

"This is no time for buck fever," I told myself. 'Take your time and make the first shot good."

A head shot would have been a sure kill, but I wanted that rack. I decided to zero in just behind the front leg and try for the heart. Gently I eased in a round, moved the crosshair of my scope onto his side, squeezed the trigger, and my 180 grain bullet slammed home. If I had been on ground level the shot would have been perfect. But, from my elevated position, the bullet angled down just missing the heart. The big buck bounced off through the trees and with him went my hopes for a trophy. Quickly, I jumped down from the stand and legged it toward the timber. A heavy blood trail lead me to a small clearing, then a fence. Hair on the barbed wire told me my buck had jumped over, so I crossed. Then, I saw the huge buck lying motionless in the grass.

I walked up on the deer, laid my rifle in the grass next to the animal, and unsheathed my knife. As I admired my trophy, I reached down with my left hand and grabbed hold of the antlers to lift up the head. My plans were cut short, however, and the next few moments gave me dreams that startled me out of deep slumber for days to come.

With the antlers around the left and right side of my body, that big whitetail sprang to his feet. When he did, the antlers caught in my flight pants and ripped them from knee to waist. To me, it was as if a ghost had come to life. I didn't have much time to think, but as the animal stumbled for footing I plunged the 7-inch knife blade into the left side of his neck, 10 inches below the head. The buck stepped on my rifle as he got (Continued on page 36)

DOG-DAY LARGEMOUTHS

Worm is equalizer when sun fights us at Medicine Creek by Bob SnowTHE PURPLE the aquatic pplants and lazily fell to Medicine muddy hoitorn. A sleepy largemouthing an easy darted out of hiding and grabbed the pioft plastic, At the other end of the 20-pound-U^t monofilament, I "Roberts received the largemouthV, telegraphed m and drove the steel barb deep into the fish's lip.

Harlan Truscott, watching the show in amused delight, felt a light tap and doubled his rod to set the hook. The overpowering bass laced the line in and around the water plants before the Sterling, Nebraska farmer could turn him. With two big bass on at the same time Harlan and Chuck had a problem, because both fish were too heavy to be swun into 8 NEBRASKAland AFIELD the boat without a net. With Harlan's fish wrapped in the weeds, they decided to work Chuck's bass first. While Harlan fumbled for the fish scoop, the Lincolnite played his worm gobbler through a series of jumps and runs.

"Give me your rod, while you net my fish," a flushed Chuck Roberts shouted as he coaxed his bass next to the boat.

With a sure sweep of the net, Harlan lifted the 4 1/2-pound largemouth out of the water.

"Now, it is my turn to net," Chuck yelled.

To pull his fighter out of the arrow heads, Harlan put a maximum amount of pressure on his 18-pound-test monofilament. When the bass rolled to the top, he muscled the fish out of the weeds and into open water. The three-pounder was netted a tail walk later.

"Over a day of slow fishing and suddenly we hook more bass than we can handle at one time," Chuck chuckled, dropping the fish onto a stringer.

Chuck, a Lincoln newspaperman, and I have swapped outdoor tales for a couple of years, but until this mid-July trip to Medicine Creek, located north of Cambridge, we had never fished together. Plans for the trek actually came about earlier in the year during a brag session. The Lincolnite has several Master Angler Awards to back up most of his big-bass tales, but when he said that he could land bass in the dead heat of summer in any largemouth lake in the state, I figured he had lived in Texas too long. I challenged the statement and the five foot, nine-inch journalist told me to pick the lake and the time, and he would catch the fish.

Largemouths have always taken a backseat to walleye and catfish at Medicine Creek Reservoir. Although bass are regulars in spring creels, summer big mouth fishing is extremely tough in the lake because irrigation drawdown leaves most of the good bass cover high and dry. What water is left is often too murky for the sight-feeding fish. When a searing July sun had drastically lowered the water in the 19-year-old impoundment, I called Chuck and snickered a bit as we set up the trip. I thought I had finally outbluffed a Texan.

Even under normal conditions, fishing a strange impoundment is a tough assignment. Chuck had never seen the reservoir before, so he gathered together all available maps of the lake and studied water depths and shorelines. Next he contacted local fishermen and their reports were far from optimistic. The water was muddy, the weather hot, and the fish weren't biting. Chuck took the news like a betting man. He called me six times in one day to complain that the cards were stacked against him but I wasn't going to let him off the hook. We would fish. However I agreed reluctantly when Chuck asked for Harlan's help in figuring out the impoundment. The Sterling farmer is an avid outdoors man and when he isn't hunting, he is fishing.

After the newspaperman met his Saturday-afternoon deadline, the three of us headed for Medicine Creek and arrived in time to scout out part of the lake before sunset. Chuck and Harlan are artificial worm advocates. In fact, when Chuck crawls a worm over a lake bottom it is as if he can describe the underwater terrain by the way his rod, line, and worm react on the retrieve.

"It is going to be tough," Chuck said as he flipped on the boat lights. "The bottom is bare and the good bass cover is on dry land. But the fish are some where and we will find them."

The morning sun hadn't even peeked over the far hills when I heard the snorts of an angler who believes in getting up early to catch fish. Usually harder to get up than a hibernating grizzly and just as mean, I growled that it was too early for coffee and fishing.

"So, you still haven't fished with a purple-people eater," Chuck muttered as the boat rumbled away from the dock. "It takes practice, patience, and persistence to learn the worm, but it will catch more bass than any lure on the market if it is used right."

A doubter by profession, I had in the past courteously listened to Chuck's ravings about the worm, but had never given the lure a serious try. Roberts has a 40-pound tackle box filled with every lure imaginable, but when he opened the box he pulled out only a huge sack filled with worms, a small, tin box filled with tiny bell sinkers, a box of hooks, and a black, battle-scarred chugger.

"You can try any lure in the box and I will outfish you with worms and my top water lure," Chuck snorted.

The newsman's display of confidence in the worm had converted me to the role of a learner. Chuck was anxious to toss in a lure, but curbed his desire long enough to show me how to rig the worm so that it was nearly weedless.

Taking an 1/8-ounce bell sinker, he snipped off its eye, removed the wire, and slid it onto the line. After tying a 5/0 hook to the (Continued on page 45)

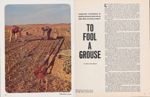

TO FOOL A GROUSE

Long-shot frustrations at prairie chickens give me an idea. Why not decoy them? by Gene HornbeckLIKE EVERY HUNTER, I have one pet frustration. That's getting close to prairie grouse. If you have ever ■■ bellied, crawled, sneaked, or run through sandburs and prickly pear trying to get within shooting range of sharptails and prairie chicken, you know what I mean. The birds frequent the hay flats, meadows, and alfalfa fields of the Sand Hills, but they have a rare knack of spotting the hunter and are smart enough to flush well out of range.

'Walking up" grouse in the endless grassland is the big challenge, for the actual hitting them is only a small part of the sport. Knowing this, I hit on the idea of "decoying" the birds in, and possibly taking the sweat out of hunting them.

After years of shooting sharptails and prairie chicken with camera and gun, I have learned some of their traits, and this knowledge influenced my decoy approach. Both species of grouse have an affinity for clover and alfalfa and fly out of the hills into the meadows in early morning and late afternoon to feed. They also feed in cut cane, milo, and cornfields. Being gregarious, grouse gather in large flocks as fall wears into winter. They sometimes scatter in smaller groups during their stay in the hills and then regroup in larger flocks to feed.

Taking this into consideration and knowing that some areas consistently attract the birds, my decoy idea seemed feasible. If they would come into a meadow, why wouldn't decoys attract them? To give the idea a chance I needed a blind and a day or two to observe a particular field and ascertain the birds' patterns. An alfalfa meadow nearly a mile long and about 200 yards wide, on the Wallace Ranch, northwest of Burwell, was selected as the test site. A big bale pile almost in the center seemed a likely spot. My decoys were made from two-inch thick styrofoam and were painted to resemble the barred markings of the prairie chicken. The semi-silhouette blocks were half again as large as an actual grouse.

Twelve full decoys were arranged in a loose flock and two more were placed atop the bales. Decoy heads on wire were set to protrude just above the alfalfa to represent foraging birds. The set made, I checked to see if it resembled birds I have seen in similar cover. After moving two or three, they looked O.K., to me, but how did they look to the grouse?

The late-afternoon sun was warm and pleasant as I leaned back in a blind of bales and awaited developments. My first visitors were meadowlarks that flitted around the field and landed occasionally near the decoys. It cheered me a little that these birds accepted the fake chickens. My next visitor was a soaring marsh hawk that skimmed over the decoys, saw me in the blind, and beat a hasty retreat.

Musing over the scare given the hawk, I almost missed seeing a lone chicken as he came winging directly over the decoys about 30 feet up. The shot would have been fairly easy, but I held off to see if the bird would decoy. I should have fired, for the bird kept flying far into the hills to the south.

Thirty minutes later, 3 birds dropped into the alfalfa about 200 yards west of the blind. Some 10 minutes later they were followed by another pair. It was nearly sunset when a threesome winged in from the hills to the north and headed right for the blind. Seconds ticked by as I hunkered deep into the bales to make sure I was hidden. The birds buzzed directly over my head and kept going. Little by little, I was beginning to pick up facts for future use, but questions were still popping into my mind. Were the birds swingingr over for a look at the spread or did the decoys just happen to be in their line of flight?

With five minutes of shooting time left, I decided to try

for the birds in the field. I crouched and headed in their

direction with little hope of getting in on them. I hadn't

covered half the distance when four birds lifted and winged

away to the north. Sure that I had seen five go in, I kept

11

moving toward the immediate area where

the birds flushed.

moving toward the immediate area where

the birds flushed.

"Must have miscounted, or the bird left, and I didn't see him," I thought to myself.

Two more steps proved my count right, for a chicken flapped into the air about 20 yards away. The modified barrel of my side-by-side boomed and the bird dropped, dead before he hit the ground. The decoys were indirectly responsible for bagging the chicken. But, I still needed more assurance that the system would work, although I felt it had promise.

The next morning, knowing that the grouse came into the fields before sunup, I was back in the blind with the first hint of light. As it turned out, a heavy fog failed to lift until nearly 9 a.m. and my second try revealed nothing. The fog had evidently kept the birds grounded. A late-afternoon return to the blind didn't add anything to my bag of birds, but I did see two doubles cross within 100 yards of my blind and land in the far end of the alfalfa. They were joined by six or eight birds as well as some singles. Apparently, they preferred a particular spot in the field, so I made a note to take advantage of their choice.

Other commitments made me give up my decoy project for almost a week. Then knowing the birds were using the far end of the field, I put up a makeshift blind in a fencerow for an evening try. The new location gave a view of the hills to the south where most of the birds came from. A half hour before sunset, a flock of chickens came for the field and my decoys. The birds winged toward me, and it looked like I would get a break. But, the birds had other ideas and landed in the canefield some 75 to 80 yards away. While watching the birds in the field, I missed a chance at a single that came in from the north and joined them. A half hour later, the flock took wing and sailed back into the south hills. Looking toward the east, I saw more birds dropping into the cane before shoot ing time ended. The birds now seemed to prefer waste grain to the alfalfa.

The following morning was a duplicate of the previous evening and I concluded it was time to move the decoys into the cane stubble. Using a small patch of standing cane along the fence, I placed the decoys in a loose flock with a few perched atop the bales and then left until late afternoon. It was nearly 4 p.m., when I was joined by Steven Kohler, a NEBRASKAland photographer. I filled him in on the project as we hiked to the blind.

"I really don't have any evidence that the birds will come in to the decoys," I said. "But I do know that some birds have flown over and looked at them."

"Being a native of Utah," Steve offered, "I've never shot a sharptail or a prairie chicken with or without decoys."

"From the looks of the activity up here yesterday afternoon and again this morning I think we're going to get some action," I replied as we topped a rise.

"They look like grouse from here," Steve said, eyeing the decoys.

I thought something looked odd about the decoys and was going (Continued on page 40)

THE PHEASANT'S DESTINY

by M. O. Steen Director, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission "Whatever will be, will be, The future's not ours to see..."THESE LINES, from a well-known song, may not apply as well to the future of the ring-necked pheasant in the Great Plains as to other predictions which a prophet might make. It is certain that no one can unerringly predict what the future may bring, but there are factors in the life of the pheasant which make certain probabilities near certainties in the future of this game bird.

To envision these probabilities we must first understand what makes the pheasant click. Many people do not. They think that pheasants increase or decrease because of foxes, or raccoons, or coyotes, severe winters, wet nesting seasons, and last but not least, pheasant seasons and pheasant hunters.

Let us take the last item first. I have said many times before, and I repeat now, that hunting has no measurable effect on the increase or decrease of pheasant populations in the northern Great Plains. The reason is very simple. Hunting here has not modified the total reproduction picture, therefore it could not have modified populations.

For the last quarter century, the hunter has been taking only the male bird. The pheasant is so highly polygamous and so elusive that it is impossible to shoot the cocks down to a level where there are not enough roosters to carry out all male functions of procreation the following spring. No amount of hunting, at any time or place in this nation, has ever reduced cock birds to such a low as to affect the fertility of pheasant eggs and therefore the production of young in the wild.

In the northern Great Plains we are accustomed to such successful hunting that we quit trying when suc cess declines greatly. We hang up our pheasant guns long before our rooster population gets down to that level which prevails when the hunting season opens in some eastern states.

The heaviest kill of cock birds ever recorded occurred on Pelee Island in Lake Erie. This island is an excellent location for pheasant research and experimentation because it has favorable pheasant environment, hence a good population, and is located in a large lake where results cannot be affected by movement of the birds either into or out of the research area.

The maximum harvest of roosters ever taken on Pelee Island was 93 percent, but yet no significant decline in the egg fertility occurred thereafter. At Prairie Farm in Michigan —a research project with which I was directly connected —a harvest approaching 90 percent of the male birds is quite common. Again, results are the same —no reduction in egg fertility and hence no reduction in the crop of chicks.

We do very well in the northern Great Plains to reach an annual rooster harvest of 60 percent. We are still wasting 30 percent or more of our fall population of cock birds, despite our liberal seasons and bag limits. This is not because we have too many roosters — it's simply because a large share of the roosters are too smart to be taken by the hunter. In fact, the real reason the Pelee Island and Prairie Farm harvests did not reach 100 percent was because the hunters couldn't do it. The bird outwits and outmaneuvers the hunter. When competing with this bird, the "mighty hunter" is mighty only in his own imagination.

The real control for hunter harvest of the pheasant under modern management is the "cocks only" regulation. Length of season and size of the bag are little more 14 NEBRASKAland AFIELD than a concession to popular —though mistaken — public opinion. A bag limit has some value in rationing the more easily taken cocks among hunters, but even here the effect is limited. The truth is, that a majority of the roosters are taken by a relatively small number of skilled and experienced pheasant hunters. Neophytes lose out in contests with this canny and elusive bird.

If you still insist that hunter take is the all important factor in reducing ringneck populations, let me remind you of some significant Nebraska pheasant history. We began hunting this bird in the late 1920's, and pheasants reached their all-time high in the late '30's. From the beginning, hens were included in the legal bag, yet pheasants multiplied and increased until the early 1940's. In 1942, we removed the hen from the legal bag, yet pheasants decreased for many years thereafter.

The simple and irrefutable truth is that pheasants increased while we were shooting hens because the environment improved, and pheasants decreased when we were shooting only cocks (which has no effect on reproduction) because their environment deteriorated. Pheasant numbers went up and up when environment was good, and down when it was not good, regardless of hunting. The legal harvest by hunters had no bearing on populations in the history of pheasants in Nebraska. The results would have been the same if there had never been an open season on this species.

To better understand this, we must first understand that the hunter harvest is not the only mortality nor even the principal mortality sustained by this species. The average annual turnover (population loss) of Nebraska pheasants is nearly 70 percent. Hunters harvest at the most 30 percent of the total population (60 percent of the cocks). Other mortalities take the balance, or 40 percent, and will take the entire 70 percent if the hunter fails to get there first.

What are these other mortalities? They are the foxes, raccoons, coyotes, skunks, opossums, cats, dogs, hailstorms, rainstorms, blizzards, mowers and other machinery, and a dozen other factors that affect the reproduction and survival of the ring-necked pheasant. To simplify matters, let us divide mortalities into two categories — hunter harvest and non-hunter harvest. Of the two, the latter is the biggest and the most important total mortality suffered by the species. Hunter harvest we can easily control, but unfortunately the game manager has little or no control over non-hunter harvest.

When the game manager attempts to control non-hunter harvest by killing foxes, for example, other predator and mortality factors take over. If the game manager could eliminate a half dozen of these mor tality factors, which would be extremely difficult to do, a dozen other mortality factors still move in to cut the population down to the "carrying capacity" of pheasant environment.

What is carrying capacity? It is the sum total of the protective elements in the range of the pheasants; the point at which non-hunter harvest is checked. Environment (call it habitat if you will) is effective against all non-hunter mortalities, but only up to that level which we call carrying capacity. The better the environment the higher the carrying capacity, and the greater the pheasant populations year in and year out.

We have, then, one simple solution for all non hunter mortality — better environment. Why don't we use it? We do use it to the very limited extent that we can, but environment is in the hands of the land oper ator. He has to manipulate environment on the land in such a way as to make a better living for himself, rather than for the pheasant.

In the 1930's, environment was good because a great depression had resulted in much idle land. A study conducted at that time in my native state of North Dakota revealed that 20 percent of the land in the better pheasant areas was idle the year around. Essentially the same situation prevailed throughout the northern Great Plains. No wonder we had pheas ants in great numbers! With one acre out of each five in habitat, producing pheasants rather than corn, wheat, milo, or alfalfa, we couldn't miss. This is the reason the birds increased to an all-time high despite the fact that we were shooting hens as well as roosters.

World War II and related events sent the price of wheat and corn skyrocketing and cattle to $40 a hundredweight. At those prices, idle acres quickly went back under the plow and the acreage of good pheasant habitat (Continued on page 44)

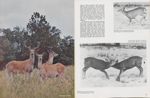

DAY OF THE DEER

This big-game animal will be around awhile. Man nearly destroyed, then restored him Photos by Lou Ell and Gene HornbeckA DEER DOESN'T have too bad a time of it in Nebraska compared to some of the lesser mammals. If he can escape the normal hazards during the first few days of fawnhood, he's well on his way to becoming an adult. Of course, he has to watch out for automobiles , deep irrigation ditches, woven wire fences, and men with rifles but these are normal hazards like crossing the street during rush-hour traffic. Unlike smaller animals, the deer doesn't have to worry about becoming a fast meal for every hungry predator that slithers, flies, pounces, or runs.

Nature was in a benign mood when she designed the deer. She gave him long legs to outrun trouble, an extremely sensitive nose to smell out trouble, big ears to hear it coming, and an inborn ability to sense it before it happens. She made him big enough to be conspicuous and then granted him a hide that blends well with practically any surrounding and just to be on the safe side, nature handed the buck a set of antlers that are no mean weapons when it comes to a showdown. Above all, she gave the deer an adapt ability to man and his works.

Nebraska's deer story follows the all-too-familiar pattern. Before the white men came to argue property rights with the Indians, the land that is now Nebraska had sizeable populations of both white tailed and mule deer. There was a gentle man's agreement between the two. The whitetails had the eastern part of the country and the timbered watercourses while the mule deer leaned toward the more open country of the west. Then as now, the two species intermingled a bit but this fraternization didn't seem to cause any international incidents in deerdom.

The first gypsy-feet who passed through

this country on their way to the fur-rich

mountains probably knew quite a bit

about deer and their scheme of life. They

knew that fawns are born in the late

spring and that their natal coats are a

marvelous blend of brown and white that

practically melts into the surrounding

landscape. They also knew that a fawn

has an instinctive discipline that keeps

him motionless when the doe is away. Observation

told the early travelers that

fawns grow rapidly and usually stay with

NEBRASKAland AFIELD

19

their mothers for almost a year before

going on their own. Men with their eyes

on the beaver pelts of the West and the

expectations of rip-roaring good times at

the annual fur rendezvous probably didn't

consider it earth-shaking information

that deer wear red coats in the late summer

and early fall and then change to a

warmer dusky tan when it gets cold but

they knew about it.

their mothers for almost a year before

going on their own. Men with their eyes

on the beaver pelts of the West and the

expectations of rip-roaring good times at

the annual fur rendezvous probably didn't

consider it earth-shaking information

that deer wear red coats in the late summer

and early fall and then change to a

warmer dusky tan when it gets cold but

they knew about it.

Deer got into real trouble here and else where when the country started filling up with land-hungry pioneers. Settlers with a soddy full of hungry mouths looked at deer as meat on the table today and to blazes with tomorrow and the future of the herds. Excessive killing and habitat alterations brought about by man's activities almost exterminated the deer.

Fortunately, some far-sighted individuals made noise enough to alarm the powers that be and laws were passed to protect the deer before it was too late. Penalties for killing deer became stiff enough to give the most hardened poacher pause.

20 NEBRASKAland AFIELD 22

NEBRASKAland AFIELD

22

NEBRASKAland AFIELD

Deer populations in NEBRASKAland are relatively stable at the present time and will probably remain so for the forseeable future. But there is a threat to their continued prosperity. Right now, this threat is small and far, far away, but it is there. Again, it is man, who may be the exterminator.

Someday, someone is going to have to ask a mighty leading question: "Which is best, another high-rise apartment here, a super highway there, a shopping center someplace else, or a herd of deer?"

Let us hope there are enough people around with enough guts to answer, loud and clear.

"Deer!"

THE END

BOOTSTRAP BOBS

Our feet do all the barking as we stage a "doggone good hunt at Pressey by Jim Burdick as told to Gene HornbeckAS SO OFTEN happens, our quail hunt started . out with a rooster pheasant. He got up with ^ startling suddenness, cackling all the way. My partner, Dan Carpentar, and I weren't going out of our way to hunt pheasants, but I wasn't about to let one fly out from under my feet without trying for him. My 12-gauge over-and-under, bored improved and modified, was loaded with No. 7%'s, so I hurried a little to catch up with the rooster as he towered toward the top of the canyon. The first shot failed to do the job, but I followed through, established my lead in front and above, and touched the trigger. The ringneck folded.

"You had me worried," Dan called as I retrieved the bird. "I thought you might let him fly away, seeing we decided on a quail shoot today."

"Shot this one for those dogs we left at home. He'll help ease my old pointer's disappointment in not coming along today if I show him a rooster that sat tight long enough to get a shot," I grinned.

Dan, a supervisor for a surgical supply and manufacturing firm in Broken Bow, is just as enthusiastic about hunting as I am. He owns an English pointer and whenever my farming and his schedule permit we gun for pheasants and quail. My farm, east of Broken Bow, is also a good dog-training ground during the summer and early fall. This hunt, however, was different.

Dan had made the statement that he couldn't remember what it was like to hunt without the aid of his pointer. His thought triggered an idea. Maybe it would be good if we brushed up on hunting techniques without dogs. I wondered if we could find quail and if we downed any, could we find them with any consistency? Dan agreed that such a hunt might be interesting.

We started shortly after sunup at the Pressey State Special Use Area along the South Loup River, a few miles north of Oconto. This public-hunting area has some good bird cover since the Nebraska Game Commission is managing the area for game production as well as servicing the camping and picnicking fraternity.

Our first quail action came when a single buzzed out from the end of a food plot. Dan swung his 12-gauge autoloader and dropped the bob with one shot. He kept his eyes on the spot where the bird fell as he hurried to retrieve his prize. I kept my eye on the spot, too, but Dan found the bird almost immediately.

The incident sparked recall of techniques that we had used before we had dogs to do the retrieving. We used to help each other find birds by marking the fall of each one. Often we would place an empty shell, a hat, or a handkerchief at the spot where we shot from and then repeat the marking system where we thought the game fell. If we didn't find the bird immediately, we would make ever-widening circles until we did. Loose feathers were also a help in locating downed birds, but this could be misleading if the wind was brisk. We knew that feathers drift downwind so the trick was to look upwind for the kill.

That first quail was evidently a loner since further tramping proved fruitless. A side draw with a mixed planting of corn and milo was next on our list and that's where I stirred up my rooster.

"Sure wish I had that pointer along to go up that sidehill and work out that plum brush," I moaned.

"I wonder how many birds we've walked by. We've been hunting almost an hour now and haven't jumped a covey," Dan replied.

We hunted for another 30 minutes, but two hens and a rooster that flushed out of range were all we stirred up. A little (Continued on page 43)

RUI AND RINGNECKS

Africa is a hemisphere away, but white hunter" picks Nebraska for his first try for the exotic pheasant by Dick Mauch as told to NEBRASKAlandRUI QUADROS walked into the cafe at Mason City looking somewhat frozen and apprehensive about Nebraska's winter weather.

"I'm not sure I'll ever get warm," he remarked to Alex Legge. "Man, this is a far cry from southeast Africa."

I introduced Rui and Alex to Harry Boyles, a Mason City area farmer, who was going to host us for some pheasant hunting. Our hunt had been planned some days earlier when I learned that Rui, a "white hunter" from Africa, was in the United States and wanted to hunt some NEBRASKAland pheasants. Rui and I had met when I was in Africa on safari. I'm a salesman for a well-known archery company and I live in Bassett, Nebraska when I'm not out somewhere hunting. While on that African hunt, I bagged a good leopard and several antelope with my bow.

"Rui has never hunted in the snow and cold, or ever shot in the U.S.A. He would especially like to knock off some of our ringnecks," I explained to my companions.

A call to Harry had set up the hunt, but he had cautioned that it would be tough.

"The birds are bunched up in what little cover is available above the snow and they are mighty hard to approach," he warned.

Alex, who also farms in the Mason City area, agreed to go along. Since the drive-and-block method appeared to be the best way to handle the spooky ring necks, we were glad to have him.

Rui gave us a little background on himself as we lunched. He is Portuguese and works as a professional hunter for an outfitting group called "Safariland". It is headquartered in Lourenco Marques, Mozambique in Portuguese East Africa. Asked about hunting seasons in Africa, my visitor told us that hunting runs from April to November there. We were full of questions, but a look at our watches suggested we get after the pheasants before the day ran out.

It was nearly 3 p.m. before we got in the field, a few miles south of Mason City. Harry was right, the ring necks were wild. Rui and I were the only ones to get shooting. Our bird came streaking downwind above the trees and both of us missed by comfortable margins. We justified the misses by claiming the rooster was jet propelled.

28 NEBRASKAland AFIELD"There's only one way to hunt this patch," Harry commented as we hiked back to the car. "Tomorrow, let's put a couple of blockers on the upwind side and then make the drive."

"I'll say one thing," Rui remarked. "Your birds are smarter than anything we have in Africa. The bustard, one of our large game birds in Mozambique, is wary and a strong flier but these ringnecks put him to shame."

"By the way," he inquired, "I saw a rabbit that looks something like the ones we have in Africa. Is the season open on them?"

"Right," I answered. 'You can shoot quail, rabbit, squirrel, and pheasant. Tomorrow morning we should get a chance at all of them."

That evening we talked more about hunting. While Alex, Harry, and I asked about Africa, our guest was very much interested in Nebraska and its wildlife. I acted as a shortstop for questions on both as my recent trip to the dark continent was my second. When asked about small game in Africa, Rui answered:

"We have quite a variety. I mentioned the bustard — he could be termed the turkey of Africa. Of course, there is the ostrich, but he is protected in our hunting area. By the way," he grinned, "you wouldn't need more than one ostrich for your American Thanksgiving dinner— 200 pounders aren't uncommon."

"Let's talk about something more our size," Alex laughed. "How about quail?"

"We have quail but they are migratory. They are the Pharaoh or Coturnix. When the birds come in the shooting is fantastic," Rui answered.

At mention of the Coturnix I told him that we had stocked some 75,000 of them in parts of Nebraska, but the stocking was not successful.

"As I understand it, Rui," I questioned, "this bird is found in Asia as well as in Africa?"

"Right," he smiled, "I don't know where our birds go. We do not have very extensive information on many of our birds and animals. Let's say the conservation movement in many African countries is just getting a start. Money to conduct surveys, research, and pay law-enforcement officers is just not sufficient to do an adequate job."

"I'm sure anyone interested in wildlife would enjoy our continent. Being prejudiced, I think the best is in East Africa," continued Rui. "It fascinates me to see your American wildlife — perhaps their numbers are indicative of tomorrow's Africa.

"When I read of your American West," he went on, "and the fantastic herds of bison that roamed here just over a century ago, I can't help but think of my country 100 years from now. Your wildlife populations have dropped because of the highly sophisticated industrial and agricultural society."

"Agreed," I said. "Wildlife habitat is becoming critical in many states. It certainly is in Nebraska, especially with this heavy snow. There just isn't enough cover to sustain all of the birds more than a few weeks under these conditions."

"I have hunted about as long as I can remember," Rui resumed, "and I can see the effects of civilization on our game herds as Africa awakens to its rich future. Agriculture has tremendous potential with such things as irrigation, heavy machinery, and advancing knowledge of farming practices."

The talk turned to other game such as the squirrel and rabbit. "Very few people (Continued on page 38)

HELP AFIELD

Here are some tips that will make your Nebraska hunt successful and safeCarrying a loaded shotgun in a motor vehicle on a public road is a violation of Nebraska law. Here's a tip to avoid arrest and fine: carry your unloaded shot gun cased until you reach the game covers. Remember, too, a loaded shotgun in a vehicle is dangerous. Protect your self and others by leaving that favorite scattergun empty and cased while traveling.

■ Don't forget to sign your permit and upland-bird stamp before you hunt. If license is lost, contact the permit vendor where you purchased it and get a duplicate license form. Fill it out, have the vendor verify it, and send the duplicate with $1 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska 68509 for a replacement.

■ The weather is often warm during the early seasons. Field dress your game as soon as it is bagged. Leave the feathers or fur on unless you have a cooler, and don't leave game in the trunk of a car unless it is parked in the shade. Hang and cool big game as soon as possible or get it to a locker plant.

■ Pheasant hunters who occasionally flush bobwhites will have an edge if they carry a few spreader or brush-load shells along with their heavier loads.

■ Cut down losses of downed birds by pinpointing the spot where the bird fell. Mark the approximate spot with an empty shell, a hat, or a handkerchief, then search the area by circling.

■ Sandburs can be a problem in some parts of Nebraska. Start early training your hunting dog to wear dog boots.

■ Remember to leave a fully-feathered leg or the head on your grouse and pheasants for easy identification of species and sex. Waterfowl must have one fully-feathered wing left on.

■ Picking a duck can be rough, but this tip can help. Dry pick the large feathers, then melt a pound of paraffin in two gal lons of hot water. Dunk the duck in the mixture and allow to cool until the wax forms a glaze. A pound of paraffin will take care of four to six ducks. Peel off the covering and then singe off the few hairs remaining on the bird by holding it over a gas burner or a flaming piece of paper. Discard the used paraffin or re melt and skim the feathers off.

■ Hunting weather is often unpredic table. Put a change of clothes in your car; it can be a lifesaver after a sudden drenching.

■ Running straight at a rooster pheas ant will often "freeze" him long enough for a shot.

■ Investigate isolated patches of cov er even if they are small. Often they hold a surprising number of pheasants and/or quail.

■ A quick move over the brow of a choppy will sometimes catch a sharp tailed grouse dead to rights.

■ Don't forget to rack in another shell as soon as a bird goes down. He some times has company. Besides, you may need that second shot for a stopper.

■ Here's one for bob white gunners. When a covey flushes toward a shelter belt or tree claim, look for the birds to be down on its far side, especially if there is heavy grass cover.

■ Nebraska's ringnecks are pretty cool customers, but a lone hunter can unnerve them into a fatal mistake by the step-step-stop method. The gunner who moves slowly and makes frequent pauses will sometimes have his patience re warded by a rooster who can't take the uncertainty of "Does he see me or does he not?"

■ Don't give up hope if a flock of sharp-tailed grouse flush wild. Move right in to the spot. Often there will be a laggard who hangs back after his com panions have departed.

■ Snuffing the covers can be dry work, so carry enough water along for both you and the dogs.

■ Losing a billfold can ruin any hunt, so when jump hunting Nebraska's marshes for waterfowl, wrap your wallet in a plastic bag and pin it to an inner pocket with a large safety pin.

■ Don't write off a shot at a deer as a miss. Often the animal will show no re action, although solidly hit. Check it out. Tufts of hair, flecks of blood, or an abrupt switch in the animal's direction are all hints of a hit.

■ Game is often wiser than we think and is quick to diagnose our intentions. Sometimes this can be an advantage. A casual, non-direct approach toward an animal or bird will often let you get within shooting range. Avoid looking directly at the potential target and make haste slowly.

■ Dog-pushed rabbits run in circles, so when friend beagle jumps a bunny don't try to run him down. Take a break and wait. Pretty soon, the cottontail will come back to within yards of his starting place. Then it's rabbit in the pan if you do your part.

■ Honking at a pretty girl will prob ably draw either a smile or a frown from the subject, but honking at pheasants may put a ringneck or two in the coat. A blast on the horn in pheasant country will often bring a challenging reply from an old rooster. Pinpoint the location and go to work on him.

■ Five minutes' careful study of terrain will give you the edge on that canny ring-necked pheasant. If you can come at him from the "back door", the element of surprise is in your favor.

■ Slamming a car door near pheasant cover is like yelling, "Hey, bug out, there's trouble coming!" Ease out of the car, shut the door quietly, and move in swiftly but silently.

WHERE TO HUNT NAME AND LOCATION NEAREST TOWN -0 km a. n to m km m TO as ex u to cr TO gj lw 4 aj to =3 TO U TO C3. to mm TO TO t_ aj -0 QJ km. Acreage mm C TO to TO OJ TO =3 C9 M 33 O t_ C3 * O t_ ■1 *—> TO mZ3 TO QJ 1— cr 00 >-> =3 Om •a Cm QJ C3. O OJ to t= mZ3 TO C-3 = CO. E TO QJ z= m. 1=1 QJ (J CO O-OJ E 0 0 ac mm to OJ ce QJ 00 =3 O 1— OJ QJ t/O to o> -E3 TO ►— la u Q. €/» OJ CJ CO OO OJ CO 1— ►— c mZZ to Lt- REMARKS:

m TO —J SB

Killdeer Basin, 3 miles east, 1 l/2-miles north of Wilcox on county road Wilcox F-8 • 38 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Killdeer, 2V2 miles north of Martell on county road Martell E 12 • 69 20 • • • •

Krause Lagoon, 4 miles west, 3V2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F 10 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Lake McConaughy, 11 miles north of Ogallala on Nebraska 61 Ogallala D-4 • 5,492 34,760 • • • • • • • • • • • • • Privately owned lodging available

Lake Ogallala, 9 miles north of Ogallala on Nebraska 61 Ogallala D-4 • 339 320 • • • • • • • • •

Lange Lagoon, 2 miles south, 1/2-mile east of Sutton on county road Sutton E-10 • 160 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Lewis and Clark Lake, 15 miles north of Crofton on Nebraska 98 Crofton B-ll • 1.227 31,000 Privately owned lodging available. Area extends along shoreline from Gavins Point Dam to Santee, Nebr.

Limestone Bluffs, 6 miles south of Franklin on Nebraska 10, 2% miles east on county road Franklin F-9 • 479 • • • • •

Lindau Lagoon, 6 miles south, 4 miles east of Axtell on county road Axtell F-8 • 131 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose. Entrance on Venule line, west side of section

Lochlinda, Wmile north, 2 miles east, Venule south, lWmiles east from Alda Interchange on 1-80 Alda E-9 • 25 35 • • • • • Fishing in Platte River

Long Bridge, 3 miles south of Chapman on county road Chapman E-10 • 108 86 • • • • • •

Long Lake, 20 miles southwest of Johnstown on county road Johnstown B-7 • 30 50 • • • • • • • • • • •

Long Pine, northwest of Long Pine just south of U.S. 20 Long Pine B-7 • 154 • Trout fishing. Center of good grouse and antelope territory. Local inquiry recommended

Louisville, V^-mile southwest of Louisville on Nebraska 150 Louisville E-13 • 142 50 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Mallard Haven, 2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F 10 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Malonev Reservoir, 6 miles south of North Platte off U.S. 83. Marked access road North Platte D-6 • 132 1,000 • • • • • • • • • •

Massie Lagoon, 3 miles south of Clay Center on Nebraska 14 Clay Center F 10 • 670 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Medicine Creek, 2 miles west of Cambridge on U.S. 6-34, 7 miles north on access road Cambridge F-7 • • 6,726 1,768 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Concession-rented trailer space. Public trailer spaces available also

Memphis, just north of Memphis on Nebraska 63 Memphis E 12 • 160 48 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Merritt Reservoir, 26 miles southwest of Valentine on U.S. 83 Valentine A-6 • 6,146 2,906 • • • • No hunting permitted north of a line from boat ramp and parking area to west abutment of the dam

Metcalf, 14 miles north of Hay Springs on county road Hay Springs B-3 • 1,317 • • • • •

Midway, 6 miles south, 2 miles west of Cozad on Nebraska 21, along 1-80 Cozad E-7 • 38 • • • • • • •

Milburn Diversion Dam, 2 miles northwest of Milburn on county road Milburn C-7 • 317 355 • • • • • • • • • •

Moger Lagoon, 3 miles east of Clay Center on Nebraska 41, 3 miles south on county road Clay Center F 10 • 120 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Nebraska National Forest (Bessey Division), entrance west of Halsey on U.S. 2 Halsey C-7 • 90,350 US. Forest Service land. Check at headquarters for special regulations

Nebraska National Forest (Niobrara Division) 10 miles south of Nenzel on Nebraska 97 or by trail west from Merritt Reservoir Nenzel A-5 • 116,000 • • • • • • • • U.S. Forest Service land. Check at headquarters for special regulations. Campground under development

Nebraska National Forest (Pine Ridge District) lies east and west of Chadron along U.S. 385 Chadron A-3 • 102,392 • • • • • • • • Two camping areas. Red Cloud picnic grounds 5 miles south of Chadron, 1 mile east on access road. Spotted Tail campground, 10 miles south of Chadron on U.S. 385, just west of highway. Public hunting areas are marked

Nine Mile Creek, 3 miles east of Minatare on U.S. 26, 7 miles north on county road Minatare C-2 • 180 • • • • Stream fishing

WHERE TO HUNT NAME AND LOCATION NEAREST TOWN -0 km a. n to m km m TO as ex u to cr TO gj lw 4 aj to =3 TO U TO C3. to mm TO TO t_ aj -0 QJ km. Acreage mm C TO to TO OJ TO =3 C9 M 33 O t_ C3 * O t_ ■1 *—> TO mZ3 TO QJ 1— cr 00 >-> =3 Om •a Cm QJ C3. O OJ to t= mZ3 TO C-3 = CO. E TO QJ z= m. 1=1 QJ (J CO O-OJ E 0 0 ac mm to OJ ce QJ 00 =3 O 1— OJ QJ t/O to o> -E3 TO ►— la u Q. €/» OJ CJ CO OO OJ CO 1— ►— c mZZ to Lt- REMARKS:

m TO —J SB

Killdeer Basin, 3 miles east, 1 l/2-miles north of Wilcox on county road Wilcox F-8 • 38 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Killdeer, 2V2 miles north of Martell on county road Martell E 12 • 69 20 • • • •

Krause Lagoon, 4 miles west, 3V2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F 10 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Lake McConaughy, 11 miles north of Ogallala on Nebraska 61 Ogallala D-4 • 5,492 34,760 • • • • • • • • • • • • • Privately owned lodging available

Lake Ogallala, 9 miles north of Ogallala on Nebraska 61 Ogallala D-4 • 339 320 • • • • • • • • •

Lange Lagoon, 2 miles south, 1/2-mile east of Sutton on county road Sutton E-10 • 160 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Lewis and Clark Lake, 15 miles north of Crofton on Nebraska 98 Crofton B-ll • 1.227 31,000 Privately owned lodging available. Area extends along shoreline from Gavins Point Dam to Santee, Nebr.

Limestone Bluffs, 6 miles south of Franklin on Nebraska 10, 2% miles east on county road Franklin F-9 • 479 • • • • •

Lindau Lagoon, 6 miles south, 4 miles east of Axtell on county road Axtell F-8 • 131 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose. Entrance on Venule line, west side of section

Lochlinda, Wmile north, 2 miles east, Venule south, lWmiles east from Alda Interchange on 1-80 Alda E-9 • 25 35 • • • • • Fishing in Platte River

Long Bridge, 3 miles south of Chapman on county road Chapman E-10 • 108 86 • • • • • •

Long Lake, 20 miles southwest of Johnstown on county road Johnstown B-7 • 30 50 • • • • • • • • • • •

Long Pine, northwest of Long Pine just south of U.S. 20 Long Pine B-7 • 154 • Trout fishing. Center of good grouse and antelope territory. Local inquiry recommended

Louisville, V^-mile southwest of Louisville on Nebraska 150 Louisville E-13 • 142 50 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Mallard Haven, 2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F 10 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Malonev Reservoir, 6 miles south of North Platte off U.S. 83. Marked access road North Platte D-6 • 132 1,000 • • • • • • • • • •

Massie Lagoon, 3 miles south of Clay Center on Nebraska 14 Clay Center F 10 • 670 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Medicine Creek, 2 miles west of Cambridge on U.S. 6-34, 7 miles north on access road Cambridge F-7 • • 6,726 1,768 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Concession-rented trailer space. Public trailer spaces available also

Memphis, just north of Memphis on Nebraska 63 Memphis E 12 • 160 48 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Merritt Reservoir, 26 miles southwest of Valentine on U.S. 83 Valentine A-6 • 6,146 2,906 • • • • No hunting permitted north of a line from boat ramp and parking area to west abutment of the dam

Metcalf, 14 miles north of Hay Springs on county road Hay Springs B-3 • 1,317 • • • • •

Midway, 6 miles south, 2 miles west of Cozad on Nebraska 21, along 1-80 Cozad E-7 • 38 • • • • • • •

Milburn Diversion Dam, 2 miles northwest of Milburn on county road Milburn C-7 • 317 355 • • • • • • • • • •

Moger Lagoon, 3 miles east of Clay Center on Nebraska 41, 3 miles south on county road Clay Center F 10 • 120 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Nebraska National Forest (Bessey Division), entrance west of Halsey on U.S. 2 Halsey C-7 • 90,350 US. Forest Service land. Check at headquarters for special regulations

Nebraska National Forest (Niobrara Division) 10 miles south of Nenzel on Nebraska 97 or by trail west from Merritt Reservoir Nenzel A-5 • 116,000 • • • • • • • • U.S. Forest Service land. Check at headquarters for special regulations. Campground under development

Nebraska National Forest (Pine Ridge District) lies east and west of Chadron along U.S. 385 Chadron A-3 • 102,392 • • • • • • • • Two camping areas. Red Cloud picnic grounds 5 miles south of Chadron, 1 mile east on access road. Spotted Tail campground, 10 miles south of Chadron on U.S. 385, just west of highway. Public hunting areas are marked

Nine Mile Creek, 3 miles east of Minatare on U.S. 26, 7 miles north on county road Minatare C-2 • 180 • • • • Stream fishing

■ A zigzag approach down main street will give the neighbors the wrong impression, but it's just the ticket in pheasant covers. It confuses the birds, thwarts their attempts to double back, and just generally keeps them guessing.

■ If known quail covers fail to produce on any given day, don't despair. Try it again the next day. Weather conditions play an important role in bobwhite behavior. Also, hot, windy days are tough on dogs and curtail their scenting ability. Cool days with little wind and a hint of moisture in the air are just about perfect.

■ Drawstrings on parka hoods are miserable things to tie, especially when your fingers are cold. A bolo-type slide is a mighty handy gadget for snugging up that hood when ears and cheeks start turning blue.

■ When hunting prairie grouse, check plum-brush patches and wild-rose areas carefully. The birds consider them prime covers.

■ After a fall, check your firearm. A barrel clogged with mud, sand, or snow can be as lethal as a hand grenade.

■ Giving out with a Bronx cheer by pursing the lips and expelling air forcefully will sometimes send pheasant skyrocketing out of dense cover.

■ Don't twang the wires when you are crossing fences. The strands act as telegraphs and birds 300 yards away will get the message.

■ If doe deer seem curious and somewhat hesitant in the open, watch behind them. Sometimes a buck sends out his girl friends before revealing himself.

■ When you're hunting the Sand Hills, park your vehicle on the highest hill you can. It makes it a lot easier to find.

■ Nebraska mule deer are curious creatures. Often they'll break with a rush, run a hundred yards or so, then stop to see what all the commotion is about. Wait them out; a standing shot is always easier than a running try.

THE ENDWHOM TO CONTACT FOR LOCAL HUNTING INFORMATION

AURORA-Chamber of Commerce, P.O. Box 146, Phone 694-3474 AUBURN-Chamber of Commerce, Phone 274-3521 ALLIANCE—Nebraska Game Commission District Office, Box 725, Phone 762-5605 BASSETT — Nebraska Game Commission District Office, Box 34, Phone 684-3511 BROKEN BOW-Chamber of Commerce, 315 South Eighth, Phone 872-5691 CHADRON -Chamber of Commerce GENOA —Chamber of Commerce, Allen B. Atkins, Secretary, Phone 993-6664 LINCOLN — Nebraska Game Commission District Office, Wildlife Building, Phone 477-3921 NORFOLK-Chamber of Commerce, 112 North Fourth, Phone 371-4862 NORFOLK - Nebraska Game Commission District Office, Box 934, Phone 371-4950 or 371-4951 NORTH PLATTE-Nebraska Game Commission District Office, Route 4, Phone 532-6225 SUPERIOR-Chamber of Commerce, Hotel Leslie, Vernon McBroom, Manager TECUMSEH- Chamber of Commerce Complete listing of all area Conservation Officers can be found on page 3.IT'S ALL A MATTER OF CARE

IF YOUR WIFE scowls every time you walk through the door with wild game, chances are there is a reason. My troubles started two hunting seasons ago when my wife, Ellen, invited a few friends over for a game dinner. She spent several hours preparing the meal, cleaned the entire house, and bragged to a neighbor that her pheasant recipe just couldn't be beat. But that night it was. The ringnecks had a "gamy" taste, the grouse was even worse, and the only meal-savers were the quail. When every one had left, my wife had a few well chosen words for the hunter in the family.

I did a little research on the problem of bad-tasting game and came up with a very simple solution. Good taste depends on the treatment of the meat just after the kill, and I wasn't spending enough time in that area. With proper game care, I found I could get wild meat to the table with its meant-to-be flavor still intact, and better yet, my wife didn't have to worry about gaminess ruining an otherwise delicious dinner.

The methods of handling all game after the kill are similar. Whether you shoot a deer or a pheasant, the quarry should be properly bled, dressed, and cooled as soon as possible. Why? Meat contamination from body wastes and juices are the

WHERE TO HUNT NAME AND LOCATION NEAREST TOWN

Sandy Channel, 1/2 miles south of Elm Creek interchange on 1-80. Marked by access sign Elm Creek E-8 • 133 47 • • • • • •

Schlagel Creek, 11 miles south of Valentine on U.S. 83, 4 miles west on Sand Hills trail Valentine A-6 • 440 1 • • • • • Limited waterfowl hunting on the creek. Limited pheasant hunting

Schramm Tract, 7 miles south of Gretna on Nebraska 31 Gretna D-13 • 276 • • • •

Sherman Reservoir, 4 miles east of Loup City on county road Loup City D-9 • • 4,721 2,845 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Sininger Lagoon, 2 miles south of McCool Junction on U.S. 81. 3 miles east on county road or 5 miles north of Fairmont on U.S. 81, 3 miles east on county road McCool Junction or Fairmont Ell • 160 • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Sioux Strip, 2 miles southeast of Randolph on county road Randolph B-ll • 25 • • • Three separate areas as posted along abandoned railroad right-of-way

Smartweed Marsh, 2Vz miles west of Edgar on Nebraska 119, 21/4 miles south on county road Edgar F 10 • 40 • • • Approximately 34 acres of marsh

Smith Lagoon, 6 miles south of Clay Center on Nebraska 14, 3V2 miles east on county road Clay Center F 10 • 128 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Smith Lake, 23 miles south of Rushville on Nebraska 250 Rushville B-3 • 420 200 • • • • • • • • • • • •

South Twin Lake, 19 miles south of Johnstown on dirt road, 3 miles west on trail road Johnstown B-7 • 107 53 • • •

Stagecoach, 1 mile south of Hickman on county road, 1/2 mile west on access road Hickman E-12 • 412 195 • • • • • • • • • •

Sutherland Reservoir, 2 miles south of Sutherland on Nebraska 25 Sutherland D-5 • 36 3,017 • • • • • • • • • •

Swanson Reservoir, 2 miles west of Trenton on U.S. 34 Trenton F-5 • 3,957 4,974 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Concession-controlled trailer spaces

Teal Lake, 2 miles south of Kramer on county road Kramer E-12 • 66 34 • • • • • •

Theesen Lagoon, '/2-mile north of Glenville on county road Glenville F 10 • 80 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Two Rivers, 1 mile south, 1 mile west of Venice on U.S. 73 Venice D 12 • 643 320 • • • • • Controlled waterfowl hunting. Check at area headquarters. Archery deer hunting only

Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, 13 miles south of Valentine on U.S. 83, west on State Spur 483 Valentine A-6 • 61,000 11,000 • • • •

Verdon, '/2-mile west of Verdon on U.S. 73 Verdon F 14 • 29 45 • • • • • • • • • •

Victor Lake, 4 1/2 miles north, '/2-mile west of Shickley on county road Shickley F-10 • 238 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Wagon Train, 2 miles east of Hickman on county road Hickman E-12 • 720 315 • • • • • • • • • • • • • Waterfowl hunting effective November 1

Weis Lagoon, 2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F-10 • 160 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Wellfleet. '/2-mile southwest of Wellfleet on county road west of U.S. 83 Wellfleet E-6 • 115 49 Two privately owned cabins, concession-controlled trailer space

Whitetail. '/2-mile west of Schuyler on U.S. 30, 3 miles south on county road Schuyler D 11 • 185 31 • • • • • • • • Fishing in Platte River

Wildcat Hills, 10 miles south of Gering on Nebraska 29, then a short distance east on access road Gering C-l • • •

Wilkms Lagoon, 1 mile south, 1 mile east of Grafton on county road Grafton E-10 • 501 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall Area is identified by blue and-white sign of flying goose

Wood Duck, IV2 miles west of Stanton on Nebraska 24, 2 miles south, 1 Smiles west, 1 mile north on county road Stanton CI 1 • 311 26 • • • • • •

Wood River West, 3 miles south of Wood River on county road Wood River E-9 • 13 15 • • • • • • • • • •

Yankee Hill, 2V2 miles east, 1 mile south of Denton on county road Denton E-12 • 728 210 • • • • •

Yellowbanks, 3 miles north of Battle Creek on Nebraska 121, 2'/2 miles west, '/2-mile north on county road Battle Creek C-il • 254 5 • • • • • • • • Fishing in Elkhorn River

WHERE TO HUNT NAME AND LOCATION NEAREST TOWN

Sandy Channel, 1/2 miles south of Elm Creek interchange on 1-80. Marked by access sign Elm Creek E-8 • 133 47 • • • • • •

Schlagel Creek, 11 miles south of Valentine on U.S. 83, 4 miles west on Sand Hills trail Valentine A-6 • 440 1 • • • • • Limited waterfowl hunting on the creek. Limited pheasant hunting

Schramm Tract, 7 miles south of Gretna on Nebraska 31 Gretna D-13 • 276 • • • •

Sherman Reservoir, 4 miles east of Loup City on county road Loup City D-9 • • 4,721 2,845 • • • • • • • • • • • •

Sininger Lagoon, 2 miles south of McCool Junction on U.S. 81. 3 miles east on county road or 5 miles north of Fairmont on U.S. 81, 3 miles east on county road McCool Junction or Fairmont Ell • 160 • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Sioux Strip, 2 miles southeast of Randolph on county road Randolph B-ll • 25 • • • Three separate areas as posted along abandoned railroad right-of-way

Smartweed Marsh, 2Vz miles west of Edgar on Nebraska 119, 21/4 miles south on county road Edgar F 10 • 40 • • • Approximately 34 acres of marsh

Smith Lagoon, 6 miles south of Clay Center on Nebraska 14, 3V2 miles east on county road Clay Center F 10 • 128 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Smith Lake, 23 miles south of Rushville on Nebraska 250 Rushville B-3 • 420 200 • • • • • • • • • • • •

South Twin Lake, 19 miles south of Johnstown on dirt road, 3 miles west on trail road Johnstown B-7 • 107 53 • • •

Stagecoach, 1 mile south of Hickman on county road, 1/2 mile west on access road Hickman E-12 • 412 195 • • • • • • • • • •

Sutherland Reservoir, 2 miles south of Sutherland on Nebraska 25 Sutherland D-5 • 36 3,017 • • • • • • • • • •

Swanson Reservoir, 2 miles west of Trenton on U.S. 34 Trenton F-5 • 3,957 4,974 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Concession-controlled trailer spaces

Teal Lake, 2 miles south of Kramer on county road Kramer E-12 • 66 34 • • • • • •

Theesen Lagoon, '/2-mile north of Glenville on county road Glenville F 10 • 80 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Two Rivers, 1 mile south, 1 mile west of Venice on U.S. 73 Venice D 12 • 643 320 • • • • • Controlled waterfowl hunting. Check at area headquarters. Archery deer hunting only

Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, 13 miles south of Valentine on U.S. 83, west on State Spur 483 Valentine A-6 • 61,000 11,000 • • • •

Verdon, '/2-mile west of Verdon on U.S. 73 Verdon F 14 • 29 45 • • • • • • • • • •

Victor Lake, 4 1/2 miles north, '/2-mile west of Shickley on county road Shickley F-10 • 238 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Wagon Train, 2 miles east of Hickman on county road Hickman E-12 • 720 315 • • • • • • • • • • • • • Waterfowl hunting effective November 1

Weis Lagoon, 2 miles north of Shickley on county road Shickley F-10 • 160 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall. Area is identified by blue-and-white sign of flying goose

Wellfleet. '/2-mile southwest of Wellfleet on county road west of U.S. 83 Wellfleet E-6 • 115 49 Two privately owned cabins, concession-controlled trailer space

Whitetail. '/2-mile west of Schuyler on U.S. 30, 3 miles south on county road Schuyler D 11 • 185 31 • • • • • • • • Fishing in Platte River

Wildcat Hills, 10 miles south of Gering on Nebraska 29, then a short distance east on access road Gering C-l • • •

Wilkms Lagoon, 1 mile south, 1 mile east of Grafton on county road Grafton E-10 • 501 • • • Land and water acreage varies with rainfall Area is identified by blue and-white sign of flying goose

Wood Duck, IV2 miles west of Stanton on Nebraska 24, 2 miles south, 1 Smiles west, 1 mile north on county road Stanton CI 1 • 311 26 • • • • • •

Wood River West, 3 miles south of Wood River on county road Wood River E-9 • 13 15 • • • • • • • • • •

Yankee Hill, 2V2 miles east, 1 mile south of Denton on county road Denton E-12 • 728 210 • • • • •

Yellowbanks, 3 miles north of Battle Creek on Nebraska 121, 2'/2 miles west, '/2-mile north on county road Battle Creek C-il • 254 5 • • • • • • • • Fishing in Elkhorn River

No. 1 spoilers of gunshot game. Although a shotgun or rifle is an essential, many hunters forget that a sharp knife, wrapping paper, a small bag, and a clean cloth are also important tools of the sport.

Most sportsmen know that immediate cleaning of big game is a must, but few realize that small game should be given the same attention. To field dress a rabbit or squirrel, simply split open the body cavity from the chest to the tail, pull out the entrails, and wipe out the cavity with a cloth or grass. If you are nearly ready to head home, skinning the animal while it is still warm makes the job much easier. Just make a circular cut around the middle of the body, grasp the edges of the severed skin with a hand on either side of the cut, and pull toward the ends. Open the body cavity, bend the legs up over the back, and give the animal a quick downward thrust. The entrails will fall out. Clean the gutted carcass thoroughly, then drop it in a bag for sanitary keeping. If you anticipate a long day in the field, small game should be field dressed but not skinned. The fur protects the meat against contamination and excessive drying.

The best way to spoil a bird hunt is to bring a bird home spoiled. Grouse, especially, will taste gamy if they are not field dressed immediately. Pheasants, quail, and turkey can stand some car trunk hauling, but the best bet is to field dress them right on the spot. To remove the entrails, cut from the back of the breast to the vent and make another cut from the front of the breast to the neck to remove the crop, lungs, and windpipe. Wipe out the cavity with a clean cloth or grass, and if possible, hang the birds from a game strap for quick cooling while you are walking the fields.

Hunters who have had early-morning success but who plan to stick around until their buddies limit out will find it worthwhile to drop their birds off at a game processor for cleaning. Birds shot early should not be carried around all day if it can be helped. If they have to be, avoid stacking them close together. Body heat from a mountain of game will help spoil the meat. A big cooler with room for both ice and birds is always a good bet. When transporting upland birds be sure to leave the heads and feet on for identification, and on water fowl, one full wing.

Dressing a duck or goose in the field is literally a matter of taste, but hunters will find that a freshly killed fowl is much easier to pluck because the feathers have not tightened to the skin. While high flyers are eyeballing your decoys you can take your exasperations out on their already-downed cousins by plucking them. To dry-pick waterfowl, pull down on the feathers to avoid tearing the skin. Cut out the oil gland at the base of the tail, remove the pin feathers with a knife or tweezers, and singe the fine "hair" by burning a lightly twisted piece of wrapping paper. After removing the entrails, keep the birds cool and wrapped in paper or in a bag.

Although a hunter may be planning a steak dinner as he walks up on a deer or antelope, the meat is still a long ways away from home. If he wants to enjoy 34 NEBRASKAland AFIELD those steaks, there are two important points to remember in field dressing a big-game animal—bleed the deer or antelope well and cool the carcass as soon as possible. Your working tools in this case are a hefty, sharp knife with at least a 4V2-inch blade, a hand ax, some rope, clean rags, and a piece of cheesecloth.

To assure proper bleeding, turn the deer so that the head is downhill and make a deep cut across the throat through the jugular vein. There are two schools of thought on throat cutting. Some hunters always do it. Others say that field dressing is bleeding enough. While the deer is bleeding, cut the musk glands from the legs but be sure to clean your knife afterwards. The musk can contaminate the meat. Now you are ready to hog dress your animal. First make a shallow cut in the midline of the stomach just to the rear of the breast. Facing the rear of the deer or antelope, put your knife hand inside the cut, angling the knife point back toward you and continue to cut to the crotch, being careful not to puncture the digestive tract. Cut around the anal opening, pull back the skin, and cut through the belly membrane for access to the intestines. If it is a buck, cut the sex organs away and tie off the bladder. Reach inside the body cavity and slice through the diaphragm, then cut the windpipe and gullet high up the throat. This done, turn the carcass on its side and dump out the entrails and lungs. Put the liver and heart in a cloth bag to keep them clean.

Rapid cooling is the secret to bringing home good meat. Split the breast and hipbones with a hand ax. With the carcass completely open, it should be hung in a shady spot either head-up or headdown to finish draining and cooling. If you intend to mount your trophy, avoid getting blood on the head or neck. To remove blood stains, sponge with luke warm water. After wiping the body cavity with a clean cloth, spread it open with a stick. To discourage flies and other insects, sprinkle black pepper on the exposed flesh.

By using these helpful hints when I am in the field, my spoiled meat troubles are over. At our house a game dinner now means good eating.

THE END Accommodations, Guides, Processing, and Meals SPECIES REMARKS

NEAREST TOWN MAP GRID NAME AND LOCATION PHONE

BRIDGEPORT C-2 DeLux Motel 26 $5-$12 12 units

BROKEN BOW D-8 Arrow Hotel, off southwest corner of square 872-2491 $2.75 • 70 pheasant

Mrs. Paul Hudson, 5y2 miles west on Highway 2, turn left, short distance 872-5445 $12 4 pheasant

Mrs. Murray's Court Perfect Motel 872-2433 $7 up 15 units

BURCHARD F-13 Andrew Schultz, 2 miles south, 1 mile west, l'/i miles south of Lewiston 865-4548 $12.50 10 pheasant, quail freezing, no charge