NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS August 1968 50 cents A LESSON IN BLUEGILL A COLORFUL VISION OF MARI SANDOZIand ZOO TIME AT DOORLY THE CHARM OF SNAKING

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.— Editor.

FIRST-TIME ARCHER-"It all started on June 15, 1967, when my son, Ron, and I applied for rifle-antelope permits. I forgot to sign my check, so I lost out, but Ron got his. It wouldn't be any fun for him to hunt alone, so since archery-deer season was open, I applied for and received an archery permit.

"I had never shot a bow in my life, but I bought a good 40-pound bow and two bales of straw. Before long, I was able to put eight arrows in an eight-inch target. Arthritis bothers me, so I limited my range to about 40 feet.

"On opening day, Ron and I hunted the Charles Gudgel Ranch in eastern Cherry County. The ranch has an alfalfa field about half a mile from the house, so I started out and hid behind one of the stacks.

"About sundown, I saw five deer coming into the field, but they were a long way off. I turned my head and there, less than 100 yards away, were 2 deer, a young buck, and a doe. They were working toward me.

"Nocking an arrow, I waited until the buck came up to within 35 feet and fired. The arrow caught him in the chest for a good lung shot. He ran about 50 yards and went to his knees. A second arrow at 10 feet finished him off. The next day, Ron bagged his antelope with his rifle." — Charles H. Kitchen, Lincoln.

WHERE'S THE FAMILY?-"I read a copy of NEBRASKAland and it made me homesick. I once lived in Omaha and Louisville. The thought occurred that through Speak Up I might be able to locate some members of my family still living in Nebraska.

"I have several families of cousins near Adams where my grandparents once farmed. They are the children of Theodore and Etta Barr Faulhaber. My cousins, Art and Dena Faulhaber, used to write, but I haven't heard from them in years.

"I would deeply appreciate any help in locating these members of my family. My address is:" —Mrs. Pearl V. Allen, 144 Marquette, Creve Coeur, Illinois 61611.

COUNTRY STORES?-"Last summer we enjoyed a motor trip across the country, returning to the east through Nebraska on your new through way. It was our pleasure to picnic at one of the delightful shelters you have so thoughtfully provided for the tourists on this road.

"Because I was born and raised in Nebraska, I know that its food products are among the best in the world. We talked as we picnicked along the highway of the good advertising value to the state's products, and of the help and pleasure to the traveler, that wayside 'country stores' might prove to be.

"If at each end of the throughway, a state-operated food stand could be placed at a wayside stopping place, the traveler could be provided with Nebraska fresh butter, bread baked in home kitchens, fresh-roasted ears of Nebraska corn, smoked sausage, ham, cheese, eggs, both fresh and hard-cooked, cookies, doughnuts, fresh milk —and anything else that I know is produced better in Nebraska than anywhere else.

"This is but a suggestion to your Parks Commission." — Mrs. D. Campbell, North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

OLD MAGAZINES -"I have many back issues of NEBRASKAland and Outdoor Nebraska, back to 1954. I wonder if anybody would be interested in them?" — Mrs. Roy Bernt, 3119-14th Street, Columbus, Nebraska 68601.

THE BEST —"We wish to commend you for the truly wonderful rest areas along Interstate 80.

"We haven't traveled all the states of the Union but at least half, and you offer the traveler the best.

"We tell everyone we know about it. We think it shows extreme thoughtfulness and kindness for your fellowmen."— Mr. and Mrs. E. Kappel, Milwaukee, Wis.

TOUCH OF HOME-"The color pictures of storm and thunderhead clouds in the June NEBRASKAland are beautiful. I have never seen more beautiful sunsets anywhere than in my native Nebraska.

"While making a trip to Omaha last fall with a friend, we watched a sunset near Ogallala change from brilliant

pinks, yellow, and gold, to deep purple and copper. It lasted a long time and the changes from color to color were very gradual.

"I still like my native state, although I've lived in Oregon for 58 years. But it always seems I am coming home when I visit Omaha." —Mrs. Edith Robertson, Portland, Oregon.

TRUE, TOO —"I recently found this short poem and thought I would send it to Speak Up.

Where the West Begins Out where the handclasp's a little stronger. Out where a smile dwells a little longer, that's where the West begins. Where there is more of singing and less of sighing, Where there is more of giving and less of buying, And a man makes friends without half trying. That's where the West begins."My father got the poem on a leather souvenir from Pikes Peak in 1924." — Jane Pedersen, Belden.

THREE FOR THREE —"I thought you might be interested in this picture of a successful deer hunt in the Pine Ridge area the last week of October, 1967. We hunted on the ranch of Fisher Gillett, about 20 miles southwest of Crawford. We got three nice mule deer, but did not get the biggest ones we saw. The day before the season opened we were out scouting the country and saw some real trophy bucks, but they did not happen to be around when the season opened. Of the three we took, one dressed out at over 200 pounds, one at 180, and one at about 130.

"I took mine at about 100 yards, W. H. Alexander got his at about 35 yards,and Dave Van Winkle got his at about 350 yards. Mine was shot with a 7.7 Jap, scoped, Alexander's with a 7.62 Russian, open sights, and Van Winkle used a .30/06 Springfield with scope.

"We plan to hunt the Pine Ridge area again next year, for never have we seen so many deer and so many big bucks. The fourth day of the season we saw six does in one herd. Mr. Alexander saw 22 does and 2 bucks in another herd. This was in just driving around over two large ranches."-Marvin L. Johnson, Leavenworth, Kansas.

6 NEBRASKAlandPrincess was a "drop out"

ROUNDUP

From circus to state fair, this dog-day month barks up a storm of fun for allAUGUST PAVES the way for the lazy languor of late summer in L NEBRASKAland, but despite the warmish days, this state continues to bounce with activity.

Garbed in a colorful Indian costume, Karen Sue Voigtlander, NEBRASKAland's Hostess of the Month, calls attention to the breathtaking powwows of the Macy and Winnebago Indians, plus the many other facets of NEBRASKAland fun throughout the month.

Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Howard Voigtlander of Exeter, Karen is a 1967 graduate of Doane College, where she majored in physical education. While attending Doane, she was a member of the Women's Recreational Association, Varsity Field Hockey Club, candidate for Doane's Yearbook Queen, dancer in Doane's Centennial Play "Distant Drums", and secretary of Phi Sigma Tau Sorority. She was also a contestant in the 1967 Miss NEBRASKAland Pageant. Karen enjoys all sports, dancing, sewing, and reading. She will teach physical education in Ashland's school system this next year.

However, native Indian attire is not a prerequisite to enjoy the annual Macy and Winnebago powwows which are held in late August. The events revive ancient tribal customs and ceremonies of the respective tribes. Both affairs attract thousands of visitors who share for a week the predominant culture of yesteryear's NEBRASKAland.

Heading for one's favorite water hole is an excellent way to escape the heat of a summer day, but cooling off is not the primary goal of the more than 800 expert swimmers who will converge on Lincoln's Woods Memorial Pool on August 1 through 4 for the National A. A.U. Swimming Championships. Officially tagged as the 1968 National A.A.U. Mens and Womens Outdoor Long Course Swimming Championships, Lincoln previously hosted the event in 1966 when 9 world records, 15 American marks, and 20 meet records were set. Experts estimate that some 14 world records will be topped this year. The event promises a little extra for spectators as the meet precedes the Olympic swimming trials which will be held in Los Angeles on August 24. Contestants will be competing for that Mexico trip this October.

Qualifying times set by the National Amateur Athletic Union must be met in previous competition to merit entry by the water speedsters, while divers must have a major win to their credit plus undergoing rigid pre-meet qualifications. Complying with A.A.U. rules, contestants must be 12 years of age or older, and be registered as amateur athletes.

Nebraska's Czech Capital breaks loose with an array of fun and festivities on August 3 and 4 as Wilber honors its Czech heritage during the Nebraska Czech Festival. Thousands of visitors from across Nebraska and several neighboring states converge on the community which is 90 per cent Czech or of Czech descent. Everyone takes part, youngsters and old-timers alike. The womenfolk bake up delicious mouth-watering kolaches and other tasty treats, while pop takes care of the fiddle and provides polka music galore. The youngsters are on hand to run errands and do odd jobs, but there's always time for fun and frolic. Colorful motherland costumes are worn to add that Old World atmosphere. Parades, contests, and plain good fun add up to make the festival one of the biggest shebangs of the summer.

The Annual Neihardt Day in Bancroft on August 4 takes on a new look this year, as Governor Norbert Tiemann proclaims the celebration for Nebraska's poet laureate be observed statewide. The ceremonies center about Neihardt's study in Bancroft where he wrote some of his most important works. Neihardt will speak at the ceremonies, while an art display from Joslyn Memorial Art Museum will also help highlight the celebration day.

Nebraska's capital city will roll with action August 6 through 18 as Lincoln hosts the National R.S.R.O.A. Roller Skating Championships. Expert skaters from all parts of the U.S. and overseas will gather at Pershing Auditorium for 14 days of top-notch competition. Roller-skating hockey leads off, followed by art and speed championships, while the final event, the Gold Skate Test, tops off the action. This is the ultimate test in skating and only the best can qualify. Age for participation begins at eight and has no upper limit. A highlight for the colossal event is a special show, "Roller Skating Spectacular", staged by professional skaters.

Cowboys and spectators alike will have plenty to see and do in Burwell and Ogallala during August. Nebraska's Big Rodeo erupts in Burwell August 7 through 10 as cowhands and rangy critters meet head on in the arena. Nebraska's Cowboy Capital blows its top August 10 through 12 as (Continued on page 54)

WHAT TO DO

1-2 —Shrine Circus, Norfolk 1-3-Festival, Table Rock 1-3 —Sioux County Fair, Harrison 1-4-A.A.U. Swim Meet, Lincoln 2 —Fireman's Picnic, Friend 2-4-Multi-Breed Horse Show, Grand Island 3 — Annual 4-H Horse Show and Livestock Show, Brady 3-4 — Pine Ridge Gun Collectors' Fourth Annual Show, Crawford 3-4 —Nebraska Czech Festival, Wilber 3-4 —Rock County Fair and Rodeo, Bassett 3-5 —Annual Pawnee Days, Genoa 4 —Annual Neihardt Day, Bancroft 5-6 —Annual Celebration, Barbecue, and Tractor-Pulling Contest, Orchard 5-7 —4-H Fair and Horseplay Days, Falls City 5-8 —Burt County Fair, Oakland 6-18 —R.S.R.O.A. Roller Skating Championships, Lincoln 7-10-Nebraska's Big Rodeo, Burwell 8-10 —Kearney County Fair, Minden 8-11-Clay County Fair, Clay Center 9 —Community Picnic, Craig 10 - Old Settlers' Picnic, Hickman 10-12 —Nebraska's Largest Open Rodeo, Ogallala 10-14 —State Legion Baseball Tournament, York 10-15 —American Legion Class B State Baseball Tournament, Broken Bow 11 —Western Horse Show, Cambridge 11-14 -"101 Stampede" Cheyenne County Fair, Sidney 12-14 — Jefferson County Fair, Fairbury 12-14-Keith County Fair, Ogallala 12-14 —Nemaha County Fair, Auburn 12-16 —Adams County Fair, Hastings 13-Sept. 7 —Horse Racing, Columbus 13-16-York County Fair, York 13-16 —Gage County Fair, Beatrice 14-17 —Dawes County Fair, Chadron 14-17 —Cass County Fair, Weeping Water 15-Old Settlers' Picnic, North Bend 15 —Papillion Day, Papillion 15-17-Thomas County Fair, Thedford 15-19 —Lincoln County Fair, North Platte 16-18-Fall Festival, Curtis 16-18 —Grant County Fair, Hyannis 16-18-Wheeler County Fair and Rodeo, Bartlett 17-18-Arthur County Fair, Rodeo, and Team-Pulling Contest, Arthur 17-18-Northwest Nebraska Rock Club Show, Crawford 18-21-Fort Sidney Days and Rodeo, Sidney 19-20-Hamilton County Fair and Rodeo, Aurora 19-21—Custer County Fair, Broken Bow 19-21-Frontier County Fair, Eustis 19-22-Holt County Fair and Rodeo, Chambers 19-22-Otoe County Fair, Syracuse 19-26-Scotts Bluff County Fair, Mitchell 20-Saddle Club Horse Show, Friend 22-25 - Sheridan County Fair and Rodeo, Gordon 22-25-Howard County Fair, St. Paul 22-25-Colfax County Fair, Leigh 23 - Tractor-Pulling Contest, Aurora 23-25-Scotts Bluff County Rodeo, Mitchell 23-24-Fall Roundup and Free Barbecue Bavard 23-25 - Cherry County Fair, Valentine 24-27-Hall County Fair, Grand Island 24-25-National Old-Time Fiddlers and Country Music Contest, Brownville o^'oJ ~Say SPriPFs Friendly Festival, Hay Springs 30-31-Pancake Days, Butte 31-Fall Rodeo, Johnstown 31-Old Settlers Picnic, Sparks 30-Sept. 2-Morrill County Fair, Bridgeport 30-Sept. 5-Nebraska State Fair Late August-Macy and Winnebago Indian THE END 8 NEBRASKAland

DAY THE BANK FOLDED

by Bill Ihm as told to NEBRASKAlandOUR AFTERNOON STARTED nice and enjoyable and seemingly harmless. My wife, Judy, and I were breaking in our new 16-foot aluminum canoe by cruising down the Missouri River. Little did we realize just how much breaking-in that both we and the canoe would get before that day was over.

I am a chemist for the Nebraska State Department of Health in Lincoln and quite a canoeing buff. That early spring day, Judy and I chose Ponca State Park as our launch point.

We floated along the South Dakota shore, taking advantage of the fairly swift current and enjoying the emerging spring foliage that covered the banks. Just ahead, I noticed the river was cutting into a 20-foot bank and that the water was murky where chunks of earth were falling and dissolving.

We continued cruising near the bank, watching the huge clods plunk into the quick-moving water. I should have known better —I grew up on the Mississippi River and know the unpredictability of rivers and their shores. But I guess you can always "sense" the danger involved after an accident is over.

As we moved directly under the bank, a 10-foot-high pillar of dirt tumbled. There wasn't even time to panic as we watched it fall smackdab in the middle of the canoe. Dirt splattered us both, but luckily we missed being buried under the ton or so of moist earth. I expected the canoe to tip, but it just sank — straight down. Judy held on to the sinking craft, later explaining with typical logic that she thought she "could hold it up". I made a lunge for the side, figuring to tip the craft and empty it. But no luck. I hit the bottom of the river and was relieved to find that the water was only about six or seven feet deep. I came up quickly, worried about my wife. She's been swimming in competition since she was 11, but I didn't know how she would react to this situation. There's quite a difference in swimming for a trophy in a heated pool and swimming for your life after being plunged into cold river water. I looked around for her, but Judy was heading for shore with sure and powerful strokes.

Hopeful of finding the canoe, I dived, groping blindly, but the craft had been pushed downstream. I gathered up the bobbing life jackets and paddles and headed for shore.

Once on the bank, I took stock. Since no one was around, the choices were few-walk or swim. We decided to try a combination of both, walking upstream so the current wouldn't 10 NEBRASKAland carry us past our car when we swam across. The same foliage that we had admired from afar became a tangled web of cursed brush as we started the trek.

A mile and an hour later, we still were no closer to home. Three hundred yards away was Nebraska. At least we knew that our car was over there.

As a boy I used to swim the Mississippi, four or five times wider than the Missouri, but a lot tamer. And like I said, Judy is a powerful swimmer - but swim the Mighty Mo? I didn't like the idea, but it was either that or spend a cold, wet night on the bank waiting for help. My wife and I entered the water for an unwilling second time.

Judy headed straight across, fighting the current, while I went along with the flow and made a diagonal cut across. But about two-thirds ol the way we both ended up on the best looking sandbar I ever saw. The water hadn't been noticeably cold, but now that we were out, the spring breeze cooled us quickly. We still had at least another 100 yards to go and we were already exhausted.

While trying to garner enough gumption to go back in the water for the last lap, we heard a distant buzz. Several anxious and hope-filled moments later, a motorboat landed at our sandy haven and a much-welcome Samaritan hopped out.

Hi, folks, looks like you're having some trouble?"

Within moments, we were on our way home, minus one canoe, but thankful we were still alive.

Several weeks later, I was told a canoe that might be mine had been retrieved about five miles from where our dunking had taken place. It was my canoe, but new no longer. It was broken in; there wasn't a square foot of metal without a dent. In fact, it looked like it had gone over Niagara Falls without the protection of a barrel.

Now, I can look back on the experience and appreciate its yarn-telling possibilities for future grandchildren, but at the time, our freakish accident almost ended my interest in canoeing. Yet, my wife and I still go canoeing. In fact, we still use the same craft. All of the dents are beaten out —well, almost all. But to keep from having to beat out any more, we stay clear of tipsy banks.

THE END

MAIDEN IN THE MARSH

by Rita Jacobs as told to Fred Nelson Everything from a bottle of room freshener to a fledgling owl spice this young girl's dawn-to-dusk swamp adventureTHE GREAT HORNED owl was only a fledgling, but he was true to his fierce heritage. He could not fly, so fight he must. Following an age-old defense instinct, he fluffed into twice his normal size and awaited his pursuers. Only the spasmodic blinking of his huge yellow eyes and the nervous flexing of his talons hinted at the fear he must have felt.

As we closed toward the grounded bird, I admired his courage. He was like a gladiator of old facing overwhelming odds, but too proud to ask mercy. He clacked his beak and hissed sibilant defiances as we approached.

Our encounter with the great horned owl was only one of the adventures we encountered in a mid-May, dawn-to-dusk exploration of the marsh at the Memphis Lake State Recreation Area. The adventures included an abrupt meeting with a hen pheasant, an eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation with a bull snake, a short acquaintance with an immaculate garter snake, all dressed up in a new skin, and a session with an imaginary sea monster. We even found a bottle of room freshener in the middle of an ill-smelling swamp.

Besides the big experiences, we enjoyed the dubious pleasures of wet feet, close attachment to barbed wire, and a first-hand knowledge of last year's cattail fuzz that looks ethereal on the spring breezes, but is awfully hard to comb out of your hair.

AUGUST, 1968 13

The whole thing started when John Larson, a graduate student studying business administration at the University of Nebraska, said he was planning to spend a day in the marsh at Memphis as surcease from the strain of spring finals. John is a hunter and fisher, but he will settle for any activity that gets him outside. He operates under the theory that you can find adventure in your own backyard if you know how to look.

I have more than the average girl's interest in the outdoors, and am blessed with an extra large love for adventure, but I was skeptical of John's claim that it can be found in your own backyard. I plan to enter college this fall and major in journalism with possibly a specialty in magazine writing. When I heard of John's plans, I turned on the charm and wheedled an invitation to go along.

But back to the owl. We were walking a wooded lane on the south side of the marsh, which is located about an hour's drive east and north of Lincoln, when we found him. There was a blizzard of birdlife around us, but the owl was the most spectacular of all. John happened to look up and saw him first. I thought he was a stuffed one, but when we moved, the owl swiveled his head to follow us with his immense yellow eyes.

Finally, he glided away from his willow perch, and made an awkward landing in a clearing about 200 feet away. I thought at first the bird was hurt but John believed otherwise.

"Youngster," my companion decided. "Mavbe I can catch him."

He took off his jacket and held it like a matador's cape as he approached the ferocious-looking bird A quick flip dropped the jacket over the owl like a net and John quickly rolled the bird in its confining folds!

I didn t want to risk those feet or that beak," he explained, holding the bird toward me

I took a timid look, and then fascinated, stepped closer. The owls eyes were his most striking feature. They were like great yellow medallions punctuated by spots of black velvet. The bird looked at me and his stare was level and unafraid. Our owl might be a captive, but he wasn't a coward.

His lack of weight surprised me. As big as he was I expected him to be heavy, but the owl was unusually light. Most of his bulk was feathers

"Keep your hands away," John warned. "He would just love to tear a chunk out of a careless finger "

The owl had worked a foot out of the jacket and I examined it with respect. The talons were curved and ivory hard with tips that were as sharp as a surgeon's 14 NEBRASKAland

"You're getting a closer look at our owl than you did at the pheasant," John commented, as we continued to examine our catch.

The outdoorsman was referring to an earlier episode. It began when we had worked through a patch of cattails to one of the dikes that laced the marsh above several canal-like channels. It made a good footpath and a good viewing spot. Besides, the walking was a lot easier and I was all for that.

We were almost at the far end of the dike when a patch of yellow wild flowers caught my eye. I slid over the dike and made my way toward the tiny flowers for a closer look and a sniff of their fragrance.

Suddenly, something brown exploded under my boots. I squealed and jumped as a hen pheasant rocketed away, but John didn't rush to my side like men do in the romantic novels. Instead, he was down on his knees, peering intently at the ground.

Carefully, he parted the grass and then straightened up with a little grunt.

"There it is."

Below us was a circular nest with 13 olive-tinted eggs. I touched one and it was quite warm to the touch. John explained that the hen was incubating a "clutch".

"Clutch seems an odd term. You can't clutch 13 eggs, or can you?" I asked with feminine logic.

"No, and we aren't going to try," my outdoor-type friend answered. "Pat the grass back into place. I don't want to discourage that hen's wish for motherhood."

We patted the grass into place and walked on. From 10 feet away, I couldn't identify the nest's exact spot, and I wondered how the hen could unerringly return to her nest in all that sameness.

A water-killed stub was only a few feet offshore in one of the main lakes, and because of its peculiar shape, we called it the monster. From one angle it looked exactly what it was, a decaying remnant of a once-proud tree. But from another vantage point, it did resemble a prehistoric monster, feeding in a primeval sea. We took several pictures of it, but I didn't appreciate John's reference to the stump AND the monster when I posed with it.

We took a long lunch break and didn't resume the second lap of our exploration until almost 2 p.m. The birdlife, which had been extremely active during the morning hours, was tapering off and John explained that many animals and birds take naps during the middle of the day. It was warmer now, and for the first time, I became aware that the marsh smelled. It wasn't really offensive, but it wasn't My Sin or Chanel No. 5, either.

John had found an empty shotgun shell and was talking about duck hunting as we walked along. I heard him chuckle and turned in time to see him pick up a bottle. It was a bottle of room freshener and although the container was stained and muddy, it was evident the bottle hadn't been there too long. I was having all kinds of thoughts about someone trying to pretty up the smell of the marsh when my practical companion spoiled my conjectures with:

"Some joker was trying to kill the human smell as he waited for a deer."

A few minutes after capturing the owl, we met the Beau Brummell of snakedom. At first, I thought it was only a shadow rippling through the wind-tossed grass. Then I recognized it as a snake. John saw it, too, and pounced like a hungry (Continued on page 54)

AUGUST, 1968 15

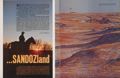

...SANDOZland

by Jean WilliamsSOME SEVEN DECADES ago, a girl was born in Sheridan County, Nebraska. In 1935, now woman-grown and mature, she gave the world the story of her father and the settlers who came to the upper Niobrara River region of Nebraska late in the Nineteenth Century. The saga was called Old Jules. The woman was Mari Sandoz.

Few of Miss Sandoz' published words for the next 31 years until her death in 1966, failed to contain at least small mention of the human or topographical aspects of this region. So impressive were her word pictures that this part of northern Nebraska has become known to western buffs the world over, as SANDOZIand.

Of all Nebraska writers, it was Old Jules' daughter who best realized, listened, learned about, and then wrote the constantly-moving drama-panorama of the Sand Hills and the Niobrara for posterity. Her first published work, and those following, portrayed the intense conflict between man and land in the Sand Hilis and on the Great Plains, more completely and accurately than anyone before her had done. Miss Sandoz's articles, stories, and books have, and will, continue to help dispel the pseudo-image of the West frequently created and projected upon the general public by various media since the days of Ned Buntline and others of his ilk. NEBRASKAland Magazine has secured permission from the Nebraska State Historical Society and the University of Nebraska Press to present passages from the works of Mari Sandoz to describe the then-and-now of SANDOZland.

"The border towns of Rock and Cherry counties were shaking off the dullness of winter. Powder smoke, lusty laughter, and the gallant curses of the young and vigorous awakened the narrow single streets running between the tents and shacks. Sky pilots plodded from town to town, preaching a scorching and violent hell. But to the west and south the monotonous yellow sandhills unobtrusively soaked up the soggy patches of April snow. Here and there a lake mirrored the windstreaked sky and brush patches darkened the north slopes where deer and antelope and the elk wandered undisturbed except by an occasional hunting party.

"The grass of 1884 was starting. Fringes of yellow-green crept down the south slopes or ran brilliant emerald over the long, blackened strips left by the late prairie fires that blew unchallenged until the wind drove the flames upon their ashes or the snow fell. Out of the east, crawled the black path of the railroad; on the plains of Texas a hundred thousand head of cattle were set upon the trails to the free lands, and from far lands came colonies of homeseekers, their wagons pushing westward, driven by man's insatiable hunger for the land.

'When Old Jules Sandoz was twenty-five he drove

his wagon up the Niobrara into the wild, free country

of northwest Nebraska. He found deer in the brush

patches, wild ducks a dark cloud in the sky, and soil

that was deep and black; a fine place to build a home

and a community of free men.

of northwest Nebraska. He found deer in the brush

patches, wild ducks a dark cloud in the sky, and soil

that was deep and black; a fine place to build a home

and a community of free men.

"It is perhaps inevitable that only those who once turned their backs upon a lush green land and faced weeks of empty prairie and sky truly realize the meaning of a tree, a garden. They have seen that a cedar upon a far bluff is sudden holiness, even a tiny garden plot a union with the strength and beauty of nature. Too long we have been immortalizing the destroyers of life, those whose greed for power and possession have been a blight upon man and the green of his land. It is time we commemorated those modest ones who worked with the earth to bring forth beauty and fruitfulness, and the hope of a new spring to us all.

"Of all the time and region, only the soil, the sun and the changing winds are unchanged. The Indians are little islands in the sea of whites. The buffaloes are gone; the grass is protected and developed and fortified by cultivated feeds, fattens the finest beef in the world. The earth holds not only the fertility for great yields of grain and other crops but also oil and who can say what further?

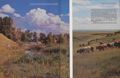

"One can still travel much of the sandhills and find practically every door open to the touch, every alfalfa patch with a wind sock. Sundays, instead of a gathering of wagons, buggies, and saddle horses to indicate where the big dinner happened to be, there is a collection of airplanes —red, blue, orange, yellow, and silver — in this or that alfalfa patch.

"Cattle, white-faced Herefords and handsome blacks, browse on the slopes with deer in the buck-brush patches and the white flag of antelope flashing the farther reaches. The great lengths of meadow are dotted with haystacks and cut by an occasional ditch, to drain, to flood as the season and the place demand. Along the foothills are the trees that the white man brought in, some ranchers with half a million planted for beauty, yes, but primarily for profit —windbreaks, snow catchers, protection for cattle, to hold them from the endless drifting into lakes and bottomless snowbanks; for whatever man has learned to control, the blizzards still howl unhobbled out of the north."

As time passes, summers sun will continue to cast wondrous glows across the whispering grasses and rolling hills. Winter's blizzards will periodically unleash their fury upon this land. Prose and poetry of others will write the constantly-moving spectacle produced by man and nature in the Sand Hills and along the Niobrara. But, due to the efforts of Mari Sandoz, its people, now-living, and those in coming generations, will always be proud to be residents of this region of fascination and provocation —SANDOZland, within the boundaries of NEBRASKAland.

THE END 20

The Charm of Snaking

Collecting is a tricky business on bring-them-back-alive trip by Bob SnowSPITTING DEATH WAS caught between a stone wall, Curt Slama, and Mick Schloff. Coiled, the buzzing 2y2-foot prairie rattler lashed out defiantly with his lethal fangs. Missing his fleshy mark, he slithered to the right, keeping his head high and alert. Curt moved in quickly, and expertly pinned the buzztail's head with a 3V2-foot snake stick. Carefully, the 19-year-old bent down, and with his thumb and index finger against the rear of the snake's jaw, he picked up the squirming serpent.

"Not a very big one," Curt said, as he counted off five rattles. "But he adds to our collection."

The prairie rattlesnake was one of six species of snakes that Curt, Mick, and I had gathered on a 3-day, 1,000-mile snake-collecting spree that ranged from around Omaha to as far west as Lake McConaughy. I have an inborn fear of anything that slithers along the ground, but as an associate editor for NEBRASKAland Magazine, I smelled a story when Curt mentioned a bring-them-back-alive collecting trip. One species, the fox snake, would be sent to the Dallas Municipal Zoo in Texas, the rest would be displayed at Omaha's Fontenelle Forest, or end up in Curt's private collection that already includes an eight-foot python.

The snake safari was scheduled for the day after Curt's freshman finals at the University of Nebraska. The Omahan has gathered over 20 species of snakes and needs only the black-headed tantilla, copperhead, Graham's water snake, and the western coach whip to round out a perfect Nebraska snake-collecting record. Curt has been catching snakes ever since he can remember, but he can't explain why he is so enthralled in his hobby. Although he hasn't decided on a college major, Curt is definitely thinking about zoo work.

On our Frank Buck expedition, I expected a trip into remoteness, but the tall, lanky teen-ager surprised me when he mapped out several spots near Omaha that he wanted to try. It didn't take Curt long to prove he knew his snakes. On a rock and dirt pile, overlooking the Platte River near the Two Rivers State Recreation Area, Curt started turning over rocks that guarded a series of small holes leading into the bank. He pulled out a two-foot-long fox snake amid a flurry of dust and debris.

"Take him back to the car and put him in the cloth bag," he instructed, shoving the snake at me. "Better bring the sack back, too."

My first impulse was to back away, but nervously I took the harmless snake. Instead of the expected sliminess, the fox snake's skin was dry and warm, and his torso soft. The idea of handling a snake still didn't appeal to me and my knuckles turned white as I clutched the squirmer. When I returned, the veteran reptile handler had a handful of fox snakes.

"Fox snakes are pretty rare in Nebraska, but I always find them in this area," Curt informed me, as he dropped them into a sack. "They are beneficial to the farmer, because they eat rats, mice, and other small rodents."

Curt continued to turn over rocks and dig back into the hillside. As he loosened one stone, five squigglers eluded his first snatch, but on the second try, his quick hands gathered in the snakes. The easy-going Omahan put a foot-long fox snake on a rock, and the normally docile reptile vibrated his tail, doubled his neck, and struck in a realistic imitation of his venomous counterparts. By the time Curt turned over his last rock, he had 15 fox snakes.

"I want to keep one big and one small snake," Curt said, as he released the rest of them. "The small one will go to Dallas. They (Continued on page 51)

AUGUST, 1968 23

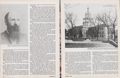

HOW NOT TO ROB THE TREASURY

A peg-leg, a tattletale. and an unarmed bandit pulled most comical holdup in West Aftermath was not so laughable

by Judy KoepkeTHEY WERE the most unlikely-looking trio of bandits in the West. One was

hampered by a wooden leg, one was unarmed, and the other was more

tattletale than robber. To make matters worse, their only getaway steed

was a very tired and very old horse. Their target was of all things, the Nebraska

State Treasury, and stickup time was midday during a legislative session when

the corridors were bustling. Their ludicrous attempt threw Lincoln into an uproar and spawned rumors that it was a farce engineered by Governor James

Dawes and a security force of three detectives on duty in the capitol. Still, one

AUGUST, 1968

25

man died, and another went on trial for his life as an

aftermath of the case.

man died, and another went on trial for his life as an

aftermath of the case.

At 2 p.m. on February 28, 1885, the foolhardy trio marched into Nebraska's treasury office in the state capitol. Bandit Alvin McGuire, who was unarmed, tried to lock the door, but the lock wouldn't work. His cohorts, Charles Daly and James Griffin, held pistols on the deputy treasurer, G. M. Bartlett, who stood alone behind a glass screen at the counter. His red mustache bright against his sandy complexion, the wooden-legged Griffin went through the counter door to peek into the vault room, and came right back.

"Some men are in the other room, but I don't believe they've seen us. I'm going to get all I can and skip."

He ordered the deputy treasurer to shell out the money. Bartlett pushed a tray of gold coins worth $435 through the opening in the glass, and Griffin dumped the loot into his overcoat pocket. He wanted to gag Bartlett, but the unarmed McGuire objected, saying there wasn't time.

Daly held a pistol to the official's head as the other two robbers backed out of the door. Immediately, two shots echoed in the hall. Daly slammed the door, ran behind the counter, opened the window, and leaped out. A detective stationed in the cellar just below the window took a potshot, but the fleeing robber made an easy escape.

The deputy treasurer sat down in the nearest chair.

Meanwhile, back in the corridor one robber lay dying. Detective Alva Pound had acted on a prior tip and stood outside the treasury door. When Griffin stepped out, Pound ordered him to halt. With the gold sagging in his pocket, the peg-legged bandit ignored the command and made for the front entrance on the west side of the capitol. Pound fired a double-barreled shotgun above his head in an attempt to stop the bandit. Griffin turned and pulled the trigger on his revolver, but the cartridge merely snapped. Pound fired again, and Griffin, riddled with buckshot, fell face down on the iron platform at the top of the stone steps.

McGuire didn't have a gun, so he considered discretion the better part of valor. When he heard Pound's "Halt", he threw up his hands and stepped back against the wall.

The detective's assistant covered McGuire, while Pound cautioned the first man to reach Griffin that the fallen robber might shoot. But the mortally-wounded man was already unconscious. He was carried into the basement of the capitol where an examining doctor counted 70 pellet holes in his back. He died two hours later. The stolen gold was promptly recovered.

Investigation revealed that Griffin had intended to mount that decrepit old horse to make his getaway after the raid. Instead, he rode in the coroner's wagon. Detective Pound may have planned it that way for this robbery was fishy from the word go.

Governor Dawes backed the story that Pound told reporters. It seems that Daly, the robber who left through the window, was a tattletale. He came to Pound with the story of the robbery plot about two weeks before the Saturday holdup. The detective ridiculed the idea, but eventually became convinced.

Pound consulted Governor Dawes who urged him to let the plot mature and set a trap to capture the robbers. He did. At first the threesome planned to visit the treasurer on Thursday at 12:30 p.m., and Pound took every precaution he could. He put one officer in the basement to guard the back window of the treasury office above. He himself took a stand in the treasury's back room at the door leading into the corridor. A third detective stood in the vault room where he could signal Pound when he heard the robbers barge in on Deputy Treasurer Bartlett. Bartlett got jittery though and ruined the attempt. He went to the door and looked out, scaring the would-be thieves away.

Later, Daly told Pound that the raid was rescheduled for Saturday and the detective took the same precautions. The robbers showed up this time and made their brazen stickup. When they started talking to the deputy treasurer, Pound's assistant signaled. The two detectives stepped into the hall and waited by the treasury door to apprehend the bandits.

When the shooting started, the senators were just gathering and the House was already in session. In those days, Nebraska had a two-house instead of a unicameral legislature. Many members ran from the legislative chambers to find out what the commotion was all about. Crowds of office workers surged into the corridors, too. A messenger rushed into the House and whispered to the speaker who in turn informed the House of the treasury raid and the gunned-down robber. Immediately, the House took a recess and joined the crowd besieging State Treasurer C. H. Willard and Deputy Treasurer Bartlett for information.

Griffin and McGuire had little going for them by way of reputations. When word got out who the thieves 26 NEBRASKAland were, the crowd's initial verdict was that both wretches should have been shot. Griffin, the dead bandit, had killed a man who came to his house one night and created a disturbance. He was cleared on the plea that he was defending his home. The 30-year-old man supported his wife and five or six children by rising garden vegetables and doing odd jobs. McGuire had been in and out of jail many times and had even served time in the penitentiary. Several years before, he was nearly convicted of a murder, but was acquitted on a plea of self-defense.

When the crowd's curiosity about the shooting was satisfied, statehouse offices resumed business, but everybody was too excited to get much done. News of Griffin's death at 4:10 p.m. added to the furor.

Governor Dawes promptly sent the senators a note calling attention to the able manner in which the detectives had protected the state treasury by capturing the robbers. As soon as the grateful senators could compose their nerves, they voted $500 to each ol the three lawmen for their efforts.

But before the day ended, rumor and hearsay began to run wild. The absurdity of the robbery, the quick damper put on it, and Daly's easy escape through the window threw suspicion on Detective Pound. Considerable talk circulated as to whether his killing of Griffin was justified.

No one had bothered to run Daly down after he leaped out of the window. But Saturday night, after no apparent pursuit, the detectives turned him over to the police. Possibly they were yielding to the suspicion that they wanted a reward, and were trying to make a reputation for themselves as notable and competent lawmen.

The public suspected further hanky-panky by the detectives when the coroner's inquest on Griffin was a secret one. The detectives claimed they were all for an open inquest, so they might be exonerated of all suspicion. The coroner countered by saying that secrecy was imposed to prevent publication of the evidence before the trial, and thereby possibly prejudicing a jury. However, the newspapers got hold of the story anyway.

By the following Monday, Lincoln was in an uproar. Many suspected the governor was in cahoots with the detectives, and public (Continued on page 51)

AUGUST, 1968 27

A Lesson In BLUEGILL

Static over fishing tipsis squelched whenwife tunes in on Verdon Lake by Mike KnepperWITH A WATERY "sloop" the red-and-white bobber disappeared beneath Verdon Lake.

"I've got one!" my wife, Jan, shouted. The taut line and bowed rod were mute evidence of the fact. I knew a nice bluegill was struggling on the No. 8 hook just beneath our boat.

A whisper of warm May wind was stirring the surface of the lake. The jade-green water reflected the lush foliage that rimmed the earthen dam where we had anchored our boat.

Excitement brightening her face, Jan reeled in. The six-pound-test monofilament sliced back and forth in the still water as the scrappy bluegill resisted with all he had, but it wasn't long before I hoisted the hefty panfish into the boat. As I removed the hook, I recalled the events that had led to this moment. The bluegill represented three firsts. He was the first fish of the day, the first fish ever for my red-headed wife, and the first fish we had ever taken in Nebraska.

My name is Mike Knepper, and the trip to Verdon Lake, named for the nearby town of Verdon in south-east Nebraska, was my first try at NEBRASKAland fishing since joining the Game Commission as a photographer-writer for NEBRASKAland Magazine. I came here after spending two years in the Army.

Earlier in the week, I had been thinking of trying for some big Nebraska bluegill. The spring weather promised to provide good panfish angling, and a quick check of the fishing reports revealed that Verdon Lake would be a perfect spot to try my luck. Besides, it was far enough from Lincoln to let me see some of my adopted state. I needed a fishing companion, but all my angling co-workers had other plans.

'Who can I take fishing with me?" I wondered out loud at home one evening.

"How about me?" answered my wife.

I reminded her in no uncertain terms that she couldn't fish a lick, but I also realized that it might be to my advantage for her to learn the angling art. If she knew how to fish, and liked it, I would always have a fishing partner close at hand, and might not run into the usual feminine wail of, "You aren't going fishing again?"

With my ulterior motives well established, I agreed to include her in the quest for bluegill. Three days later, a 100-mile drive to the picturesque state lake southeast of Lincoln put us in the middle of bluegill water where Jan made her fishing start.

An "Is it a good one?" from my wife brought me back to the present. Assuring her that a three-quarter-pound bluegill is a good one in anybody's lake, I rebaited her hook with another mealworm. I hooked it through the thin-shelled body covering near the tail and made sure that none of the hook stuck through. Some of the experts around the office had recommended mealworms, so I conned one of the fishery research people into giving me a batch. They raise them to feed the fish used in experiments.

Jan's fishing lessons hadn't progressed through casting with a closed-face reel, so I tossed out her unweighted line. The mealworm began a slow, tempting descent into bluegill country.

I barely had time to get my own ultra-light spin rig set up when my pupil shouted and started cranking in another fat panfish. I added that one to the stringer and went through the rebaiting process again, reflecting out loud on the merits of mealworms.

"These worms are popular among ice fishermen, but are sometimes neglected for spring and summer fishing," I told my (Continued on page 56)

28 NEBRASKAland

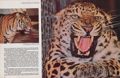

Zoo Time

Want to see a monkey kingdom, a polar bear haven, or an elegant eland? Then this 108-acre animal wonderland in heart of Omaha is place for you Photography by Richard Voges and Steve Kohler

PRAIRIE DOGS scurry hither and thither through their earthen town, while a sea lion cavorts in the "Wishing Well". Just a skip away, an owl blinks at passersby, and atop the hill otters play and badgers loll in the sun. At Bear Valley, massive grizzly and polar bears pace their dens. Homely sloth bears out-maneuver their slow-moving companions, the sun bears, while Smokey-type black bears gaze across a man-made gorge, looking for handouts. The place is NEBRASKAland's Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha.

While these and most of the other animals are definitely not for petting, there is also a spot for just that-the Ak-Sar-Ben Nature Kingdom at Doorly. There, hordes of children shriek gleefully as irresistible little goats, begging them for some treats, tug and gnaw at their coattails and cuffs. A burro strolls nonchalantly past, and a strutting bantam rooster crows his disdain in the background. At the "barnyard", youngsters can actually get into the pens with the animals. Here, there are no signs that say "look but don't touch". Quite the opposite is true, for children may fondle these tame creatures to their hearts' content.

Nestled along the picturesque Missouri River in the heart of Omaha, the zoo encompasses all of what was once Riverview Park. Hundreds of common, exotic, and rare animals and birds from the four corners of the earth inhabit the 108-acre display area. Although the park contains some 135 acres, 221/2 of them will be lost to an interchange for Interstate 80. However, zoo officials consider it land well spent, for when construction is completed, the highway will exit prospective visitors almost at their front gate.

32 NEBRASKAland

By the end of 1968, the Omaha Zoological Society will have $21/2 million invested in the project. Long-range plans for a ''complete" zoo call for a total investment of $71/2 to $8 million. Last year, Doorly's first full year of operation, 250 thousand people were educated and amused there.

To Dr. Warren Thomas, director of Doorly, a zoo must fulfill four requirements to justify its existence-education of both adults and children, research for both human and veterinary medicine, conservation, which includes the propagation of the species in captivity, and recreation for all.

Doorly meets the four criteria, but the casual visitor scarcely realizes he's learning while watching. For an outlay of only 50 cents, in addition to the regular admission fees, a family can get their own "zoo key", which opens the "Talking Storybooks" near the various animal pens. Each storybook relates interesting and unusual details about the animals being viewed.

From begging bears and show-off chimps to the extremely rare bontebok and giant eland, Henry Doorly Zoo is a delightful excursion into the world of nature. Once inside the gates, it's hard to realize that the hustle and bustle of Omaha is just outside.

A "Safari Ride" takes visitors on a two-mile lecture tour of the hoofed and large animals, while a miniature railroad provides a leisurely ride through the scenic grounds. For the energetic, it's a long, healthy walk to see all of the many inhabitants.

34

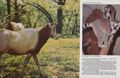

Fast becoming one of the leading zoos in the nation, Doorly boasts some outstanding residents. Many are species one expects to see, but what about a black-backed duiker (that's a small African antelope)? There are many others with strange-sounding names from faraway places.

There are the scimitar oryx and addax from Africa, both bordering on extinction. The two giant eland from western equatorial Africa are the only pair in captivity. Once reduced to 18 animals, the bontebok (another African antelope) now number just over 200, and the 5 at Doorly are the only ones in the western hemisphere.

37

Orangutans have been reduced to 2,500 animals in the wild, and requests for orangs must be made through a national placement committee, but Doorly has 2 females and 2 males, 1 on permanent loan from the federal government. The alpacas, too, are unusual zoo residents, for while they are common in the wild they are extremely rare in captivity in the United States. Rhinos are in trouble, too, for civilization is taking its toll, but Doorly has several, including a recently-acquired Indian rhino. There are less than 300 of this species left.

At Dooriy, as with most zoos, the people watch the animals and the animals watch the people. It's hard to say who is most amused, but one thing is certain, there are fascinating experiences ahead for those planning an excursion to the Henry Doorly Zoo.

THE END

The Case Against Hard Pesticides

Man, beast, bird, and fish, all face the peril of a Silent Spring. Pretty labels and extravagant claims are only camouflage for deadly poisonsTHE CONTROVERSY on hard pesticides can be compared to a one-time controversy over the shape of the earth. At that time, the Flat Earth Society challenged any or all to debate the matter. Within the radius of their vision, members of the society saw a flat land and a sea that dropped away at the limit of sight. One man, a sea captain, accepted the challenge, declaring that the earth was indeed round. His evidence - he had sailed around it. However, his experience had not been witnessed by the society, and when it took a vote, a two-to-one majority declared that the world was indeed flat.

Like the sea captain, modern biologists, chemists, and ecologists have sound evidence to support their cases against the hard pesticides, but it is not sufficiently tangible to convince all.

Advocates of these chemicals can display dead insects, records of increased crops, and certain other concrete benefits, while opponents must depend upon imponderable laboratory reports, complex ecological principles, and animal responses apparent only after long and careful observation. For example, there are no apparent long-term effects on humans as yet, but it is known that humans do store up DDT in their bodies and that DDT has a 15-year half-life. Accumulated DDT and other hard pesticides may pose threats to human health and life at some future date.

However, there is growing evidence that hard pesticides are having an adverse effect on wildlife and will continue to do so. Many experts believe that a Silent Spring is just around the calendar unless the use of these deadly compounds is curbed.

Fortunately, after a quarter of a century of using chlorinated hydrocarbons, there is a growing disillusionment with their use, as many unintended effects come to light. Resistance to these chemicals is common, 40 NEBRASKAland with over 166 insect species possessing resistance to one or more insecticides. There is also growing awareness that hard pesticides can affect non-target organisms such as beneficial insects, wildlife, and even man. We know now that some of them break down to other lethal compounds with an even higher stability, and that in addition to these liabilities, we can only place a portion of the chemical on the intended area. Tests have proved that part of a hard pesticide may be transported by air currents to be deposited hundreds or thousands of miles away to enter streams and affect a whole new living community.

The chemicals in question include DDT, chlordane, aldrin, dieldrin, Toxaphene, and heptachlor which make up a large family of insecticides known as the chlorinated hydrocarbons. Beginning with the early days of World War II, the use of these chemicals became the accepted solution to many specific insect problems. Realization of these benefits led to greater and greater use and a proliferating list of compounds. Despite the availablity of less persistent compounds, the use of chlorinated hydrocarbons rose to 350 million pounds in 1962.

These chemicals have a common characteristic of being nearly insoluble in water, but are highly soluble in lipides or the fat portion of living tissue. Since they do not break down through natural action, they build up in the tissues and are passed through the food chain without losing their toxity. Let's see how this happens.

An aquatic insect which eats smaller organisms already carrying DDT in their systems accumulates their residues in his own body. A small bluegill eats the insect and acquires his store of DDT plus that of thousands of others. Thus, the bluegill's residue may be anywhere from 100 to 1,000 times greater than the concentration which existed in the original food source. In time, a largemouth bass eats the bluegill and adds his victim's store of pesticides to his own plus that of possibly hundreds of other bluegill. A fisherman eats the bass and accumulates more of the pesticide withm himself. Since man is at the end of the food chain, he is the storehouse for all the chlorinated hydrocarbons that came before. What it will do to him remains to be seen, but judging from tests it will not be good.

Effects of these chemicals vary greatly. In many cases, death occurs. However, more often the results will be something less. The affected animal may experience reduced vigor, making it more subject to predation. Experiments have shown that behavior and learning processes may be altered, increasing the vulnerability to natural mortality. Fish which carry residues may respond to the slightest disturbance by convulsive reactions.

But the greatest peril is this: these chemicals may reduce reproductive capacity. To the ecologist, this effect is more serious than the death of these same animals. Population dynamics show that a population in which mortality occurs, has a tremendous capacity to restore the original population level. If, however, a portion of the population is rendered incapable of reproduction, but continues to occupy the environment, this recovery mechanism cannot function normally.

Already two birds, the bald eagle and the osprey, are endangered. Both of these species normally consume sizable quantities of fish, and the pesticide residues they have assimilated from this source appear to be having serious effects on their reproductive rates.

While much has been written about ospreys, eagles, robins, and other non-game species, only recently have some of the insidious effects of hard pesticides been described on pheasants. For example, Nebraska pheasant hunters will be interested in experiments performed at the Department of Wildlife Management at South Dakota State University. These show that the pesticide effects are not transferred only through food chains. They can also be transmitted from hen to chick through the egg.

An intensive study of dieldrin showed some of the subtle ways that this chlorinated hydrocarbon can affect reproduction in pheasants. Pheasants used in the tests were the offspring of hens which had been subjected to testing a year earlier. Part of the parent hens had been given measured doses of dieldrin, while others were kept free of pesticides. The young hens which they produced were also separated into groups, part of them treated with dieldrin and the rest of them given none. Thus, all combinations of treated and untreated young hens produced by treated and untreated parents were checked for their capacity to reproduce. It was found that not only can dieldrin reduce reproduction in the hens to which it has been fed, it can have a similar effect in the young which they are able to produce.

Treating hens with dieldrin resulted in the production of fewer eggs by treated hens and their young. In addition, fertility and hatchability were lowered in the offsprings' eggs.

Thus, these tests showed another of the very insidious ways in which life can be affected by the persistent pesticides. Like so many of the other effects, these changes in a natural population would be very serious, yet they would be almost impossible to detect. Aware of the South Dakota experiments, researchers with the Nebraska Game Commission are now conducting surveys to determine the extent of pesticide contamination in our own pheasant and fish populations.

Chemical analysis of pheasant hens and eggs in south-central Nebraska has revealed sizable concentrations of dieldrin (Continued on page 56)

AUGUST, 1968 41

SAGA SALLY ANN

From horses to hearses, all have used the ferryONCE AS COMMON as silver dollars and bustles, ferryboats on the Missouri River have all but disappeared. But near Niobrara, Nebraska, the last ferry on the river fights the current every day from April 1 to November 1. Called the Sally Ann, the boat, actually a stern-wheeler, although her captain, Otis Cogdill, and thousands of others refer to her as a paddle-wheeler, preserves a part of yesterday that is fast vanishing from the rivers of the world.

From dawn to darkness each day, Captain Cogdill watches over the river, passes out fishing forecasts, and waits for the red flags that signal waiting passengers. To him the Missouri is more than a river, it is a way of life. When he talks about the waterway, his words are reverent and respectful, for he and the Missouri have been partners for more than 30 years. A Coast Guard-licensed operator, Otis has been Sally Ann's pilot for four years, but his river experience dates back to 1937 when he started working towboats on the Missouri.

The river has tolerated the five-foot, eight-inch man, and although Otis hardly lives up to the conception of a huge, barrel-chested river captain, his knowledge of the Missouri's habits makes him a big man when he is behind the Sally Ann's wheel. His wrinkled, weather-beaten face hides a quick wit behind a ready smile, and even though the trip across the river is short, Cogdill's hospitality and friendly conversation make the brief voyage a remembered experience.

Otis is as easy going as the Missouri on a still summer day. When the flag signals a passage he ambles out of the Ferry Inn in his characteristic hands-in-the-pocket walk. Climbing the wooden stairs to the small pilothouse, he waves push-off instructions to his only deckhand, his daughter, Anita. A push of the starter button and the Sally Ann's 50-horsepower tractor engine coughs, sputters, and finally kicks in. The 70 by 24-foot boat trembles and vibrates with anticipation as she prepares for another battle with the river. Her red paddles, faded from constant threshing, churn the murky water into a white froth as the ferry backs away from the dock. Twenty yards from shore, Captain Cogdill cuts back the engine, turns the brass wheel, and lets a combination of rudder and current swing the Sally Ann around before heading downriver to the South Dakota dock nearly 1/2 miles away.

During the short cruise, Otis leans against a stool, his eyes always on the river and the high bluffs that guard the channel between Nebraska and South Dakota. Unlike most commercial craft on the river, the Sally Ann never gets any farther than IV2 miles away from home, even though she may log over 40 miles of river travel a day. Last year, 5,600 cars and 20,000 passengers made the

(Continued on page 50) 42 NEBRASKAland

LYNCHING At Badger Creek

Pastor-decreed penalty is harsh, but hemp justice saves a county future griefs by Irma Foulks, Ponca, NebraskaTHE BUBBLING SPRING knows a secret. But it cannot tell. Neither can the shale-covered banks of the deep ravines or the clear, flowing creek. The native pastureland, dappled with wild flowers, cannot tell either. The trees were smaller then, but they can still remember the horror of that July day in 1870.

This is now a peaceful place. While it is only three miles southeast of Ponca on Badger Creek, the surroundings appear much the same as they did when the settlers first came to this area. Looking at the peaceful scene, it is hard to imagine the events which took place there so long ago. But this is how it happened.

Two men are approaching. One is young, the other older, more mature. The young man is Matt Miller of Ponca. His companion is identified only as Dunn, a man with his heart set on buying a farm and settling down in this new state of Nebraska.

"We can get a drink of cool water here and rest awhile in the shade of these trees," the young man says. "It has been a long, hot walk from Sioux City."

"Yes," agrees his companion. "I am a little tired. But I am glad I came." Nodding his head for emphasis, he adds, "This is good country."

After a little pause, he continues. "I thought it would delay me when I missed the stage. I want to get a farm as quickly as possible and send to Clinton, Iowa, for my family."

"Farms cost money," sneers his companion.

"Yes. But I have been saving for a long time." Mr. Dunn pulls out a large roll of bills.

The young man's expression changes. Perhaps he remembers what his girl friend said earlier, "Either get some real money or get lost."

The two continue to visit, but the young man seems preoccupied and nervous. Finally, he springs into action. A knife flashes as he sinks it into the older man's chest. Again and again the blade rises and falls as the killer continues his deadly work.

The older man is limp and lifeless, but his young companion doesn't stop. He takes his victim's hickory cane and beats him in the head. His bloodlust still unsated, he takes his knife and slits his companion's throat. The potential land buyer lies silent in a pool of his own blood.

Matt Miller walks into Ponca as if nothing happened. He enters his father's saloon and pours a drink.

"I'm leaving town."

"Good."

"Got any money for me?"

"You'll get no more of my money."

"Don't need it. I could buy you out twice," the son snarls, holding out a roll of bloody bills.

"You working as a butcher? The money's bloody enough. So are your shirt sleeves."

But Matt Miller stayed in Ponca for the Fourth of July celebration, then left early the next morning.

That same day, hunters came across Dunn's mutilated body. Sheriff M. B. Dewitt began the search for Miller and soon brought him back. A large crowd was waiting.

The crowd seized Miller and roughly escorted him to the Lutheran Church which served as the courtroom. The pastor, now judge, opened the hearing with a prayer. After the prisoner pleaded guilty, a vote was taken as to his fate. Almost unanimously, the 500 people present voted that he should be hanged. The pastor pronounced the sentence.

Matt Miller was placed in a wagon and taken to the present Ponca school site. A gallows, consisting of three limbs joined together at the top, had been prepared for the lynching. After the rope was securely tied about his neck, the wagon was driven out from under him. In a few minutes, the grisly work was done, and the young man's body dangled from the makeshift scaffold.

The body was cut down and taken back to the church where, only an hour before, the trial had been held. A funeral was held the next day.

This first murder and lynching had one good effect for Dixon County. For a long time, whenever anyone planned to commit a crime he made sure he was not in Dixon County. The punishment was too severe.

Few visitors to the pleasant little spot beside Badger Creek know of the frightful act it once witnessed. Trees, flowers, and water are not the ones to tell of man's misdeeds.

THE END NEBRASKAland proudly presents the stories of its readers. Here now is the opportunity so many have requested-a chance to tell their own outdoor tales. Hunting trips, the "big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor impressions-all have a place here. If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln 68509. Send photographs, black and white or color, too, if any are available. AUGUST, 1968 45

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . DOWITCHER

A sewing machine on legs describes this spring-and-fall visitor to our state's ponds and lakes by Dan Timm, Waterfowl BiologistWHEN A dowitcher, Limnodromous griseus, feeds, the up-and-down rapidity of his head resembles that of a sewing-machine needle. A busy eater, he often becomes so engrossed in probing moist sand or mud for morsels that he allows humans a close approach.

A rather small bird, a dowitcher has a reddish breast in the spring which changes to an overall gray in the fall to match his belly. He can be easily identified in flight by a triangular patch of white on his lower back and rump. A single "keek" or a low, mellow "tu-tu-tu" are his calls.

Two different species frequent Nebraska, the long-billed dowitcher and the eastern, or short-billed. However, the two species look nearly alike and have similar habits, and are treated as one.

As a shore bird, the dowitcher is well equipped for his environment. His three-to-four-inch olive-color legs make shallow-water wading easy while a long, tapered bill is effective in finding food.

Nebraska shorelines provide resting and feeding areas for dowitchers on their leisurely spring and fall migrations. They breed from the west side of Hudson Bay across Canada to Alaska. Dowitchers winter in the southern United States and south to Guatemala. In late April, they begin arriving in Nebraska and a few stay in the state until late October.

During the May courtship, several males pursue one female in zig-zag flights until a female finally selects one mate. The male often hovers 50 feet above the female while she is incubating. A typical nest is in a shallow, mossy depression where four large, greenish-brown, spotted eggs are laid. Young hatch in 10 to 12 days and can immediately walk and pick up food. In less than a week, young birds can fly short distances. Adults cover the nestlings at night and give an alarm call when danger nears. At this call the young freeze until the coast is clear. When motionless, the drab-color fledglings are almost invisible. Within a month, the parents leave their offspring, who often get together to feed and migrate in one group.

About 90 per cent of a dowitcher's food consists of animal matter. The balance is made up of plants. Fly larvae, beetles, marine worms, mollusks, and small crustaceans are delicacies. Pondweed, smartweed, bulrush, and spikerush make up the plant diet.

Dowitchers are often confused with snipe. There are differences. Dowitchers feed in groups. When flushed, they remain bunched and fly only short distances, always landing on or near the shoreline. Snipe do not remain in a flock and commonly land in taller vegetation away from the shoreline. Also, snipe do not have the triangular white rump patches, which are easily seen on dowitchers.

THE END

DON'T LOSE YOUR COOL

Spoiled food is a camping hazard. Here are economical and efficient tips on how to solve this age-old problem by Richard VogesONE OF THE things a camper must learn is how to keep food from spoiling. There are many ways to do this, depending on the length of the trip and the number of people involved.

If you own a pickup camper, you can use a convenient refrigerator which operates on bottled gas or from a 110-voIt outlet.

Still, many outdoorsmen prefer the tent and campfire, and for them food keeping becomes a bit more thorny. However, there are portable self-contained propane refrigerators, or electric ones that operate from the cigarette-lighter outlet of a car. Other campers and picnickers use the chest-type cooler. Most of these use ice and vary in size, shape, and price.

The most common are made of styrofoam. These coolers are cheap and effective for the not-so-often camper. They will keep food cool from one to four days, depending upon the size and their ice capacity. For those who do a lot of camping, a lined cooler with an outer shell and an interior of either metal, fiber glass, 48 NEBRASKAland or other insulating material is best. These chests are rugged and long-lasting.

There are several ways to store ice in these coolers. If the outfit has a dram, chunk ice can be used. If it does not your grub might get a little wet unless you protect it from the melting ice. There are several easy and economical solutions to this problem

Home-freezer owners can fill plastic beach bottles or milk containers. with water and then freeze them. Be sure to allow room for expansion by leaving a little space in the containers. These improvised containers will keep your food cool and dry. Ice cubes can be put in plastic bags and will serve the same purpose. Cans of commercial ice are also available at stores where camping equipment and supplies are sold. These patented nntTvare Tre exPensive' hut pay off in the long run as they can be used many times

If you camp near a stream, numerous eatables can be kept fresh by the water, or by underground cooling.

Food can be placed in a plastic bag, or in a waterproof box and anchored to keep from floating away A large milk can can be weighted, and put to floltln a stream, or you can put your grub inside a burlap sack tie it securely, and float it. It is best, however to first put food in waterproof bags before placing them in any of these containers. Remember to attach a recoverv rope on these makeshift coolers. This makes it more convenient to get your food and avoids the nuisance of wading every time you want a snack.

A pocket can be dug in the sand beside a stream and lined with rock. The food cache can be set in t£ hole where it is kept cool by the seepage of water and the insulating properties of the sand. A large flat rock or a split log can be used as a cover

Some campers prefer the undergroundmethods. Dig a hole under a tree or near a stream. Sink a wooden box and place your food in plastic bags or wrapping foil inside. Food, so protected, will not be harmed by seeping water. In fact, seepage provides excellent coolling. The same type box can be put into any hole in the ground and serve the same prupose. However, a lining of wood chips, leaves, or grass, should be placed between ground and box. So protected, ice will last for a long time.

Building a rough-and-ready camp cooler with wooden shelves is simple. Use plywood or similar material. Cut 4 or 5 shelves about 14 inches square, and drill 1/4-inch holes in all 4 corners of each. Cut four pieces of sash cord, five feet long, and tie an overhand knot on one end of all four. Thread a rope through each corner of a shelf, and pull it down against the knots. Tie another overhand knot in each rope, eight or nine inches higher, and thread on another shelf. Continue this procedure for the rest of the shelves, and when you thread on your last one, bring all the ropes together and tie them off. Suspend this contraption form a branch, and wrap old burlap around it for covering.

Leave a slit or overrapped opening in the burlap to provide access to the intrior. Let the burlap extend at least 10 inches above the top shelf. Place a pan of water on the top shelf, and fold the burlap down into it. Siphoning action will dampen the burlap clear to the bottom of the cooler, and evaperation of this moisture will lower the internal temperature by many degrees less than the outside air. Always hang this cooler in a breezy, shaded place.

Naturally, ice or mechanical refrigeration are the best for keepign food, but these imrpovised methods are suitable and a book to the sometimes camper, who doesn't want to tie up cash in a more elaborate outfit, but still avoid the risk of going hungry, or worse yet, getting food poisoning.

THE END AUGUST, 1968 49

SAGA OF SALLY ANN

(Continued from page 42)trip across the river, and on one single day the ferry made 23 round trips and carried 162 cars. In a pinch, the ferry can tote eight cars, but seven is a practical load. In his tenure as captain, Otis has hosted tourists from Panama, South America, Canada, Germany, Holland, Czechoslovakia, and every state in the Union except Alaska.

Riding the ferry is a real bargain for tourists. When ferries were common on the Missouri, fares were 75 cents to $1 for a wagon and a team and 5 to 10 cents for foot passengers. The Sally Ann's rates are $1.65 for a car and its driver, plus 15 cents for each additional passenger. The trip across river with the current takes about five minutes, while the trip back is three times as long.

"People ask me if the paddles are just for show," Otis said with a wrinkled grin. "Without them we wouldn't get too far; they are an essential part of the Sally Ann power plant."

The ferry is a tourist attraction, but it is also a practical means of getting across the river. The nearest bridge is at Gavins Point Dam, nearly 40 miles away. Cattle trucks, buses, ambulances, and even hearses have used the Sally Ann. Otis has even made a baby run or two for expectant mothers rushing to a hospital on the South Dakota side of the river.

"Once I thought I was going to have a baby born right on the ferry," Otis smiled. "That was the fastest run I ever made across the river, and I guess the mother made it to the hospital all right. Her husband forgot to pay me, which was natural under the circumstances, but a few days later he came back and gave me the fare."

In slow, carefully-punctuated words Otis drawled, "An 80-year-old man who rode the Sally Ann was retracing his footsteps in life. He told me he ferried his covered wagon across the river at Niobrara a good number of years ago."

Captain Cogdill's ferry is the last of a once-sizable fleet that plied the river, hauling passengers and equipment from one shore to another. The first record of a commercial ferry at Niobrara shows that a Captain Leach skippered a double-deck, steam-power paddle-wheeler as far back as 1902. Then, as now, there were no bridges for several miles up and down the river, so ferrying provided a vital service. Several other craft succeeded Leach's, culminating in the Sally Ann.

The ferryboat was as much a part of Nebraska's pioneer past as the lumbering Conestoga. As early as 1820, soldiers at Fort Atkinson ferried across the Missouri. As the frontier pushed across the big river, ferry landings sprang up near Brownville, Nebraska City, Plattsmouth, Omaha, and even on the Platte River near Schuyler.

Glorious in their prime, the ferryboats died slowly with both the river and man taking their toll of the fleet. One by one, the more than 20 boats on the Missouri disappeared as an angry river crushed or punctured the wooden hulls. Gleaming iron bridges helped make the picturesque craft obsolete until only the Bertha at Niobrara remained. In the winter of 1959-60, an icy river claimed her. But the small town of Niobrara and several other Nebraskans would not let the cantankerous Missouri have her way. A propeller-powered craft, The Rex, was launched, but it was not capable of dealing with the current or the sandbars. The Rex was then replaced with the Sally Ann, named after Otis's oldest daughter. The paddle-wheeler's ability to maneuver in two or three feet of water makes her adaptable to the moody Missouri.

According to her captain, the white boat, trimmed in red and blue, will be around for a long time. The steel-hulled vessel has five water-tight compartments, so her chances of sinking are practically nil. Like all commercial boats on the river, the Sally Ann is inspected by the Coast Guard each year, and once every five years she has to be pulled out of the water for a complete inspection. Only a lack of interest on the public's part will put the Sally Ann out of business, and with her reputation as the last ferry on the Missouri there is little chance of that.

Although man has managed to harness and channelize most of the Missouri, the stretch between Fort Randall Dam and Lewis and Clark Lake is as primitive as the days when fur traders paddled upriver. A tough waterway to navigate, the channel changes constantly, with tricky sandbars and reefs building up overnight only to disappear just as quickly. Last year, Otis had to follow the Nebraska shoreline for several hundred yards before cutting across to South Dakota. This year, the sandbar barrier has shifted and he can head straight across river, but that, too, will probably change.