NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland September 1967 50 cents 8 BONUS PAGES WATER WONDER IN COLOR SPECIAL HUNTING ISSUE: BIG AND SMALL GAME ROUNDUP SHOOTERS' CHECK LIST WHERE TO HUNT ACCOMMODATIONS

SEPTEMBER NEBRASKAland

Vol. 45, No. 9 1967 SEPTEMBER ROUNDUP 9 HUNTERS' CHECK LIST 11 WILDERNESS GRUB BOX Lou Ell 12 * CHECKMATING THE CHINK 14 RALLY 'ROUND THE JEEP Bob Snow 16 A TREATY AT HORSE CREEK Warren Spencer 20 BEAR HUNTS DEER Gene Hornbeck WATER WONDER SIGHTS ON QUAIL AND GROUSE FOCUS ON PHEASANTS ON TARGET FOR WATERFOWL CROSSHAIRS ON BIG AND SMALL GAME 22 26 34 36 40 42 THE COVER: Mainlining ringneck blasts from cover in frantic flight to elude hunter's fire Photo by Gene Hornbeck SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS EDITOR, DICK H. SCHAFFER Editorial Consultant, Gene Hornbeck Managing Editor, Fred Nelson Associate Editors: Bob Snow, Glenda Peterson Art Director, Jack Curran Art Associate, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard Photography, Lou Ell, Chief; Charles Armstrong, Steve Katula, Allan M. Sicks Advertising Representative, Ed Cuddy Advertising Representatives: Harley L. Ward, Inc., 360 North Michigan Ave., Chicago, III. 60601 Phone CE 6-6269 GMS Publications, 401 Finance Building, P.O. Rov 722, Kansas City, Mo., Phone (816) GR 1-7337 DIRECTOR: M. O. Steen OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland, published mnnthi u Nebraska Game and Park per copy. Subscription rates- $3 for two years. Send NEBRASKAland, State 68509. Copyright Nebraska mission. 1967. All rights reserved Second-class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska and at additional mailing offices. NEBRASKAland

ATOKAD RACES

Enjoy the thrills of Nebraskaland's thoroughbred racing for a full 28 day season. Enjoy the comfort of Atokad's GLASS ENCLOSED GRANDSTAND, and the beauty of South Sioux City's pari-mutuel track. Better horses and bigger purses at Nebraska's newest race track. Atokad Park in South Sioux City.

Post time 2:30 P.M. Daily 4 NEBRASKAlandSPEAK UP

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. —Editor.FARM HOSPITALITY-"I have many hobbies and the main one is hunting. Through it, I have met many wonderful people and had many wonderful hunts in Nebraska.

"Though my pleasure in hunting ducks, geese, and quail on the Platte River has been very great, I think that the friendliness and hospitality of the farmers is the thing that impresses Mrs. Devine and me the most. Although much land is posted, a knock on the door or a honk of the horn insures a friendly welcome. Nine out of ten Nebraskans let you hunt on their land.

"I have always had great hunter's luck in the state and every year we return with high anticipation." —Andy Devine, Newport Beach, Calif.

SPORTSMAN'S HAUNT - "We enjoyed Nebraska when we joined archer Fred Bear of Michigan on a deer bow-hunting trip last fall. Looking down on the state from the air, you might think there is no game. All you can see is farmland, streams, houses, towns, and small patches of timber along the creek and river beds, but those small patches of brush hold some of the largest white-tailed deer found anywhere. Your state is quite a place for sportsmen with so much good hunting on private land.

"One thing sure on our next trip, we want to drop worms in an eddy in a river that does not appear over-fished. That is if we can get our buck with a bow and arrow before the gun season opens." — Murry and Winston Burnham, Marble Falls, Texas.

ENJOYABLE PLACE-"This is a bit like the proverbial busman's holiday. As a rather busy writer, I usually dread doing letters. But not long ago I made a most enjoyable trip to Nebraska for a spring turkey hunt in the Pine Ridge, and it occurred to me that I have had so many satisfying trips to Nebraska that perhaps I should drop a note to say so.

"It seems to me that NEBRASKAland is doing a fine job of pointing out to its readers that Nebraska, somewhat overlooked in past years as a recreational and tourist haven, truly does have a great deal to offer, and is by no means just a 'place to get across' on one's way to somewhere else. I could refer you to the fishing trip I made a few years ago to the lakes of the Sand Hills country. One fall I also made a run to this same region for waterfowl hunting, which proved to be top-notch. Then there was the pheasant trip to the McCook area, made several seasons ago when I had first moved from Michigan to Texas. We had a bit of difficulty that season filling limits, but nonetheless had a most enjoyable hunt. With my family I've made a number of camping and fishing runs to various parts of Nebraska over the past several years, and we have done a good bit of proper, old-fashioned touristing hither and yon over the state.

"I think the recent turkey hunt was probably the high point. I did collect a dandy gobbler. There is just one criticism I have. Let's put a stop to that business of snowstorms toward May first. They're tough on a warm-weather-transplanted Texan.

"You may be certain I'll be back." — Byron W. Dalrymple, Kerrville, Texas

DOWN ARGENTINA WAY-"My sincere and enthusiastic congratulations on Nebraska's Centennial and for the most becoming January NEBRASKAland commemorative issue. Keep up the fine work providing the sportsmen with fish and game while simultaneously keeping the balance in preserving wildlife and protecting the innate beauty of Nebraska." —Raul O. B. Hinsch, Buenos Aires, Argentina

INTRIGUED —"My husband and I were intrigued with your very untypical Nebraska scenery on the June NEBRASKAland cover, identified only as Cedar Canyon. Please, where is it?" —Mrs. R. McManus, Baltimore, Ohio

Cedar Canyon is approximately 15 miles northwest of Crawford, just off the point of the Pine Ridge where it terminates in a hill called Round Top. The canyon can be said to be the beginning of the southeastern tip of the Toadstool Park complex —Editor

BACK-ISSUE CARP-"In the May issue of NEBRASKAland, I read that the August 1966 issue contains a recipe for preparing smoked carp.

"Being a recent subscriber, I do not have that issue. I would very much appreciate you sending me the recipe." — Mrs. Emil A. Kucera, Clarkson.

Smoking is a simple process, and can turn even the lowly carp into a gourmet's delight. Oak, apple, hickory, and cottonwood can be used to create smoke, with a hot plate for heat. Chips and sawdust may be purchased commercially.

Clean and wash fish from % to IV2 pounds, or cut larger fish into uniform pieces. Place the fish or pieces in a cold salt brine for (Continued on Page 6)

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 5)24 to 36 hours. Brine is made by adding 11/2 cups of salt per gallon of water. Use enough brine to cover the fish.

After removing meat from brine, wash in clear water, and dry. Now, place fish in smoker on a rack or on hooks. If on racks, turn every hour for evenness. Smoke at 150 to 200°. Smoking may take from several to 12 hours, depending on the size of the fish. After the fish are removed from the smoker, they should be kept where air is circulating.—EditorSMOKE SHOP-"Mr. Ira Clinkenbeard of Plattsmouth wanted to make a smoker out of an old refrigerator. Here is how I made mine.

"A single-door refrigerator is best, however, I couldn't find one. Mine has a freezer compartment above which I use to store wood.

"First make sure that you take off all latches and install a different type so someone doesn't get locked inside. Strip the motor, freezing units, and insides out, saving the racks to lay fish on.

"I usually soak my wood overnight for more smoke. A hot plate supplies the heat.

"I like to keep the temperature around 150°. If higher it cooks the meat rather than smoking it. No thermostat is needed, but with the refrigerator insulation you may have to unplug the hot plate for a while to keep the heat down.

"To prepare my fish I use 1/2-gallon of water, 1 cup of salt, 1/2-cup of sugar and 1/2-ounce of pepper. Stir until all salt and sugar is dissolved, then soak fish for four to six hours. For added flavor use three or four crushed bayleaves and a couple of dashes of angostura aromatic bitters.

"After soaking fish, rinse in cold water, and dry at room temperature until a film forms on them. Then place on racks, skin down.

"Smoking takes 4 to 5 hours for small fish and as long as 10 to 16 hours for large ones. Some of the larger fish should be cut up to speed smoking." — Donald H. Crosby, Garden Grove, Calif.

THEY ARE THE BEST-"My hunting days in Nebraska started back around 1923. I was a comparative small-fry then — and my Dad started me out on rabbits, with a .22 rifle or a .410-gauge shotgun. It didn't really matter too much what I was shooting with, or what I was shooting at, as long as I was with 'my Dad'. He was quite a guy!

"Things have changed since those boyhood days back in the '20's. Rabbits are still there, I assume —but the 'bird' population has really exploded; the deer population, too. Over the past several years I have had some of the best bird shooting I've ever had in my entire life right 'back home' in Nebraska. And I look forward to it every year. Sometimes it doesn't happen that I can get there. But you can bet I am always trying.

"And it isn't entirely because I like to shoot birds. It happens that I like the people in Nebraska. They're the best, the most hospitable, the most honest, the most trustworthy people in our whole darned country. And you lucky Nebraskans who are still living there just believe me. I've been a lot of places, and I have met a lot of people, and I still say NEBRASKAland has the best hunting and the best people in the whole country. I'll be there this coming fall if I can possibly make it." —Robert Taylor, Hollywood, Calif.

OUT OF THIS WORLD-"I am interested in information as to how and why Nebraska is able to publish such a beautiful monthly magazine. The color work is out of this world.

"I am in a group interested in publishing a monthly sports and recreation magazine and would like some good pointers." —Geneva Litzel, Charles City, Iowa.

NEBRASKAland magazine is published by the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission, at a cost of approximately $14,000 per month for about 67,000 copies. It is financed by a budgeted figure from our fish and game appropriation, and also by subscriptions, newsstand sales, and advertising.— EditorRARE RABBIT-"Here is a picture of a cottontail which I shot a few miles south of Wilcox. It is hard to believe such a thing as an antler rabbit, but I have plenty of witnesses to verify it.

"The single antler was centered on the forehead and was hard, similar to a deer antler."-Wayne A. Roesler, Wilcox

The "horn" is a type of skin tumor known as a papilloma. It is caused by a virus infection and is spread by bloodsucking insects. Fleas, ticks, mosquitoes, and flies spread the virus of papillomas from infected to healthy individuals. The "horns" do not spoil the meat for eating, as they come off with the skin. Early records for the occurrence of this condition in Nebraska cottontails dates back to 1901 -Editor

6 NEBRASKAland

WHAT TO DO

Aug. 8-Sept. 4 —Horse Races, Columbus 1 — Order of the Arrow National Conference of Boy Scouts of America, Lincoln 1-2 —Pancake Days, Butte 1-4 —Morrill County Centennial Fair, Bridgeport 1-7 —Nebraska Centennial State Fair, Lincoln l-7_4-H Dairy Show, Norfolk 2 — Old Settlers' Picnic, Venango 2 — "Parade of the Century", Lincoln 2-3-Fall Festival, Brainard 2-4 —National Outboard Association International Championship, Lincoln 2-4 —Brown County Centennial Fair and Rodeo, Johnstown 2-4 —National Outboard Association International Championship, Capitol Beach, Lincoln 2-9-Horse Races, Mitchell 3 — Open horse show, Dodge 3 —Indian Dances, Boys Training School, Kearney 3-4 —Night Rodeo, Bridgeport 3-4 _ "Old Home Town Festival", Brainard 3-5 —Central Western Market Meeting, Omaha 4 —Centennial Labor Day Parade, Fremont 4-Gold & Co., 4-H Club Meeting, Lincoln 4 —State Horseshoe Tournament, Cozad 4 —Community Day, Page 4 —Centennial Pageant, Wallace 4 —Fall Festival, Arcadia 4 —Centennial Picnic Celebration, Uehling 4 — Old Settlers' Day Parade and Picnic, Lodgepole 4 —Labor Day Celebration and Picnic, Paxton 4-8-Scotts Bluff County Fair, Mitchell 6 —All-Star Pro-Wrestling, Lincoln 7 —New Car Show, Omaha 7-23 —Madison Downs Horse Races, Madison 8-9-Fall Festival, Arnold 8-10-Keya Paha County Centennial Fair, Norden 9 —Kearney State College vs. Eastern Montana Univ., football, Kearney 9 —Wrestling, Omaha 9 —Centennial Celebration and Milo Days, Carleton 9 — Farmer-Rancher Appreciation Day, Neligh 9 - Centennial "Whatzit" Day, celebration and parade, Tilden 9-10 —Salt Creek Wrangler Rodeo, Lincoln 9-11 —Nebraska Dental Assistants Convention, Omaha 10 —Blue Valley Wranglers Centennial Horse Show, Fairbury 10-11-Hay Days and State Siphon Tube Setting Contest, Cozad 10-12-YMCA-AOS Conference, Lincoln 11 —18th Annual Meat Animal Exposition, Norfolk 11—West Central Grain Coop Annual Meeting, Omaha 11-13 —Popcorn Days, North Loup 11-13 —Middle west Snipper Motor Carrier Conference, Omaha 11-13 —Federal Land Bank Convention, Omaha 12 —Concordia College School Year begins, Seward 12-13 —Federation of National Farm Loan Associations Convention, Omaha 13-15 —Richardson County Centennial County Fair and Fall Festival, Humboldt 13-15 —Midwest Chapter of Insurance Accounting Convention, Lincoln 14-16 —Nebraska Motor Carriers Convention, Omaha 14-16 —Immediate Care of the Sick and Injured Conference, Lincoln 15-17-10th Annual Plains Rock and Mineral Club Show, Kimball 16 —Kearney State College vs. Washburn Univ., football, Kearney 16 —Nebraska Wesleyan Univ., vs. Midland College, football, Lincoln 16 —University of Nebraska vs. Washington University, football, Seattle, Washington 16 —"Centennial Conversations", Nebraska authors discussion, Lincoln 16 —Doane vs. Colorado College, football, Crete 16 —Concordia College vs. Hastings College, football, Seward 16-Day of Culture, North Platte 16-17 —Nebraska Laymen's League Convention, North Platte 16-18-Range Mangement Contest, O'Neill 17 —Rough Riders Annual Rodeo, Palmyra 17 —Antique Auto Show, Brownville 17-Lutheran Hour Rally, North Platte 17-19-Nebraska Association of Soil and Water Conservation (Continued on page 57)SEPTEMBER Roundup

State Fair, football, and hunting seasons hit high note as autumn swirls into a swinging symphony of eventsTHE SEPTEMBER SONG in Nebraska is a lively melody of cheering football fans, festive gatherings, bustling scholars, and rollicking conventions. This symphony is accompanied by a percussion section as rifles crack and arrows whir with the opening of the hunting seasons. The vibrant staccato of the State Fair is countered with the discord of shorter days and dropping temperatures.

Multicolored leaves rival the flash of red hats as Cornhuskers support the University of Nebraska football team which opens its season September 16 against the University of Washington Huskies at Seattle. Big Red's first home game is on September 30 against the Gophers of Minnesota. Around the state, other college and prep teams will put their last year's records on the line.

Traditionally grouse, squirrel, and rabbit seasons are in full swing by midSeptember. Bowmen get their chance on September 16 when the archery deer season makes its debut. It runs to December 31, with an intermission from October 27 through November 5 for deer rifle season. Antelope archery season, August 19 through September 22, ends just in time for a three-day rifle season, September 23 to 25.

A special teal season, September 9 through 17, will find hunters on Nebraska's lakes, ponds, and streams. The three-shell limit still applies to migratory waterfowl, since the federal restriction is not expected to be lifted until the 1968 season.

The 99th annual State Fair in Lincoln expects a record attendance of 425,000. Lawrence Welk and the entire cast from his weekly television show will headline the event in nightly appearances from September 3 through 7.

The Hubert Castle Circus of Dallas, Texas, a grandstand attraction, with animals, clowns, and acrobatic stunts will present four performances on September 1, 2, and 3.

Floats from at least 75 counties, high stepping majorettes, blaring bands, and special units will snake through downtown Lincoln in the Parade of the Century, September 2. This Centennial Commission project, co-ordinated with the State Fair Board, will be patterned after the Tournament of Roses Parade.

Lincoln will be a Mecca for 4,500 to 5,000 Order of the Arrow Boy Scouts arriving August 28 for a four-day conference. The honor society with delegates representing all 50 states will present two public performances, an exhibition of Indian dancing and camping demonstrations at the University of Nebraska football stadium and a talent show at Pershing Auditorium. Dr. Urner Goodman, founder (Continued on page 56)

NEBRASKAland HOSTESS OF THE MONTH Diana Catherine FochtNEBRASKAland Hostess of the month, Diana Catherine Focht, is practicing her sharpshooting, so that she will be right on target for the coming hunting seasons. She graduated last June from the University of Nebraska with a degree in speech pathology, but will return to the university this fall for graduate study. During her undergraduate years, she was a member of Mortar Board, a Pom Pom Girl, Pi Lambda Theta (teacher's honorary) president, Nebraska Sweetheart Finalist, Homecoming Queen Finalist, and Big 8 Track Meet Hostess.

Last summer, Diana assisted with the Freshman Orientation program at the University but still found time to enjoy her hobbies of swimming, tennis, reading, and sewing. She is the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Focht of Lincoln, and a member of Pi Beta Phi Sorority.

8 NEBRASKAland

HUNTERS' CHECK LIST

HE TRAVELS fastest who travels lightest, so whether hunting Chinese pheasants or American deer, a sportsman should be prepared for hunting but not snowed under with a lot of needless trappings. Veterans keep their paraphernalia to a minimum, but they wouldn't be caught dead without the essentials. To avoid the, "Oops, I forgot!" lament, they keep a year-round equipment box in the garage or basement and before an expedition prepare a check list.

□ Nebraskans 16 and over and all out-of-staters must have a license. Pheasant, quail, and turkey hunters must have state upland-bird stamps. These and the licenses must be signed. A hunter must have a current license on his person when he is in the field. Waterfowlers must have a current, signed "duck" stamp attached to their permits.

□ Humpty-dumpty may have been set to be broken but Nebraska game laws aren't. Know them and obey them. Hunting guides containing current information and regulations are available from permit vendors, conservation officers, county clerks, and Nebraska Game Commission offices.

□ Go where the action is by contacting Chambers of Commerce and consulting Game Commission news releases throughout the seasons. And once the happy hunting ground is pinpointed, contact landowners for consent to tramp their fields. This should be taken care of prior to the season if possible.

□ In repayment for access privileges, the hunter should leave gates as they were, carefully attend cigarettes to prevent fires, and offer his host a share of the bag.

□ Know hunting area borders and respect the farmers' or ranchers' instructions on certain areas. When away from home, leave word where to be reached in an emergency.

□ Regular exercise puts the hunter in shape for a day of hiking and reduces his chance of heart attack. If hunting from horseback, do some riding ahead of time.

□ Man's best friend might be better off, too, with some sessions of outdoor romping and a refresher course in obedience. Dogs brought into Nebraska must have an official health permit bearing a veterinarian's certificate that they are free from disease symptoms and have current immunizations against rabies.

□ Bone up on gun safety with a National Rifle Association course or similar gun-handling instructions.

□ Polish rusty hunting skills by "sighting in" your rifles or shoot a few blue rocks with the old scattergun. A miss on the range isn't half as disappointing as a miss in the field.

□ For the finance-minded, remember travelers' checks can be cashed more readily than personal checks and a billfold can be saved from a watery demise by wrapping it in a plastic bag.

□ To camouflage or not to camouflage? That is the question. Bowmen and waterfowl shooters must blend in with their surroundings but upland-game hunters should wear a red cap or shirt as safety precautions. A bright red or yellow jacket is essential when shooting big game and if a hunter is out for mixed game, strips of red, pinned or snapped over the front and back of a neutral-toned jacket, convert an upland outfit to big-game garb. Remember, movement instead of color spooks game.

□ Compression is not good for the sole so hunting boots which fit comfortably are always a wise choice. If rain and snow are factors or if marshy treks are on the agenda, rubber hunting boots, or leather boots with rubber uppers will keep feet dry and warm.

□ Hip or chest waders should be loose enough to be kicked off in case of a dunking, but not so tight as to rub the shooter the wrong way. Check waders for leaks ahead of time.

□ Two pairs of socks are usually worn on chilly autumn days —the outer pair generally being woolen while the under pair may be cotton for cushioning and perspiration absorption or silk for further warmth. A third pair for emergencies plus a can of foot powder are luxury items which may become blessings.

□ For the clothes-conscious sportsman, long Johns (Continued on page 53)

WILDERNESS GRUB BOX

IT WAS THE little red fox that started it all. His black-button nose probed the short grass along the old railroad bed and occasionally he lifted his head, chewing ecstatically, his eyes half-closed with pleasure.

Whatever he was eating must be darned good, I thought. I hooked my thumbs under the shoulder straps of my pack to ease the load and each time the fox buried his head in the grass, I took a cautious step forward.

I had closed the gap to about 30 feet before he caught my scent and scattered cinders in his frantic escape. Ten seconds later, I was savoring the wild strawberries on which the little animal had been feeding.

I filled the drinking cup of my cook kit with the tiny red jewels, and was just rising to my feet when I noticed another plant among the grass stems. I pulled it, but I didn't bite into the white bulb that came easily from the moist earth. Wild onion doesn't mix very well with strawberries.

On the opposite side of the old railroad, a patch of marshy ground was rank with cattails. Near the open water farther out, bulbous eyes dotted the surface of the pond. Rippling into the pond, through an old culvert beneath the tracks, was a tiny stream, nearly choked with watercress. The thought popped into my mind that here, in a small area, were many of the ingredients for a wilderness meal. If a little red fox could wrest his sustenance from the earth every day of his life, I felt that I, too, could find my dinner.

Cattail roots, I knew, are an excellent substitute for potatoes. Since I had no shovel to dig them, I grasped the green stalks as low as possible, and worked the root systems from the muck. Pale, yellowish-white cones jutted from some of the heavy roots. These were the buds of new stalks, and I broke them off and laid them aside. The sprouts would be the bulk of my wilderness salad, although I could have boiled them in a cream sauce, similar to asparagus tips, for a vegetable dish.

With my hunting knife, I scraped the hair roots from the heavy tubers and cut the large pieces into manageable chunks, washing them well in the little stream. As I worked, I wondered how the alchemy of boiling converted these tough, stringy roots into a soft, tasty edible.

From a corner of my pack, I took a small plastic vial, and removed a length of fishline and a hook from it. I tied a four-foot length of line to a long stick, looped on the hook, and decorated the barb with some ravelings from the tail of my red-wool 12 NEBRASKAland shirt. The little fox would have laughed if he had seen me sneakily dangling this silly-looking lure before the bulbous eyes in the pond. Most of the eyes disappeared in a swirl of water, but some remained.

by Lou EllHalf an hour later, four husky, strong-hammed bullfrogs stuffed the old sock dangling from my belt. Had I wanted other meat, I could have searched the sandbars for fresh-water clams, or, tried for a bass, or even a carp.

I skinned the frog legs and dropped them into a small kettle of salted water. The old cottonwood, under whose arching shade I was making the meal, furnished some dead branches for a cooking fire.

My cattail roots, covered with salted water, were first to feel the blaze. After they came to a boil, I set my little reflector oven before the fire. I decided the meal would be all the better with hot bread. Though it was cheating a little, I lifted a cupful of biscuit mix from the supplies in my pack, mixed it in a small plastic bag, and patted the dough into a thin sheet. On impulse, I spooned some of the strawberries on one end of the sheet, and folded the remainder of the dough over them.

While the biscuit was puffing in the oven, I gathered a large handful of tender watercress from the stream, placed it on a plate, heaped it with cattail buds, and garnished my growing salad with thin slices of wild onion.

The first thick sticks in the fire were now raked aside with a forked stick. Minutes later, the little frying pan with a spoonful of shortening was sizzling on the embers. The frog legs, shaken in a plastic bag with a fistful of biscuit mix to coat them, were dropped into the frying pan.

By this time, the cattail roots were tender to the fork, the biscuit in the reflector was browning, and the frog legs had ceased their quivering and lay quiet in a golden crust.

Suddenly, I realized that plain water was all I had to drink. My eye caught a small green plant growing at the roots of the cottonwood. I pulled some of its leaves and the sharp, clean scent of mint rose as I rolled the leaves in my hand. I tossed them into the tiny coffeepot containing two cups of water, and set it on the coals to steep.

For some, the cattail and watercress salad might have been improved with a dash of salad dressing. But, as I ate, the fresh taste of the wilderness was in the unadorned greens, and I finished them with a longing for more. While eating the rest of the meal, I reflected that obtaining food from the wilderness need not be a problem. For those willing to learn its ways, the wilderness opens up its inexhaustible lockers, although its contents will vary with the particular area and the seasons. If there is any one rule to follow in sampling its wares, it is this: "If it tastes good, eat it!"

As I poured aromatic mint tea for a relaxing after-dinner cup, I saw a flicker of bronze in the grass along the old railroad bed. I raised my drink in a toast to the little fox who was responsible, this time at least, for the satisfying meal I had from the wilderness grub box.

THE END SEPTEMBER, 1967 13

CHECKMATING THE CHINK

This Columbus quintet knows the right moves when it comes to putting pheasants in the bagAS THE CAR eased to a stop along a field road, the five hunters slipped quietly from the vehicle, opened the trunk, and picked up their shotguns. Doors were quietly closed and the men talked only in whispers.

An inch of fresh snow lay glistening in the early-morning light of the December day. Somewhere to the north, a rooster pheasant cackled his challenge to the rising sun, and the sound brought grins to the faces of the hunters.

With a gesture, Chris Wunderlick sent three of his hunters toward a woodlot while he and his nephew, Max Wunderlick, waited silently until the three, swinging in a wide arc, disappeared behind the trees. Then they, too, moved toward the woods.

Without talking, Max stopped about 50 yards from the corner of the lot while Chris continued to a stand, some 50 yards from the other end. Kneeling, they loaded their guns, and watched the fringe of the cover in anticipation.

Action wasn't long in coming as soon as the voices of the three drivers, Buck Wunderlick, Chris's son, Dan Eisenmenger, his son-in-law, and Ves Zuerlien, called information to each other:

"Birds running ahead of me."

"Rooster cutting back toward you, Buck."

Wham! A blast from one gun and an excited "got him" triggered a hectic sequence of flying birds and booming guns as a gaudy rooster fell to one shot from Chris's 12-gauge. Max missed a bird on his first shot, but his second was on to upend the fleeing target.

Three roosters cackled into the air from the side of the woodlot, out of range of the blockers. A half-dozen hens winged straight at Max and then flared as they saw the gunner. Catching the wind the birds swept back over the trees.

It was only 10 to 15 minutes after the start of the hunt before the trio of drivers walked out of the woods with 3 of the 5 birds that were downed in the quick coup against the ringnecks.

The hunters had a note of excitement in their voices as they rehashed the action.

"Let's hit that soil-bank patch up north of here next," Chris suggested. "With this snow cover the birds should be holding in that heavy stuff* for awhile before they go out to feed."

Fifteen minutes later, the party halted on a county road beside a narrow patch of grass and weeds that ran for a half-section to the south. As they got out of the car and opened the trunk, there was a flurry of wings as at least 50 birds lifted from the cover and sailed away toward the middle of the section.

"A case in point to illustrate that you can't be too quiet before getting into a field," Chris remarked.

"We can work it out, but chances are that's the extent of the birds in the patch. The way they are bunched up now, I doubt that there are any singles left farther down the field," he continued.

The group, all from Columbus, agreed and decided to try a brome patch where some of the birds had settled. The hunters hiked the quarter mile to the tallgrass field and then spread out in a line with each man about 50 yards from his companion. They swept toward the south end, flushing only a couple of hens.

Chris, through years of hunting Nebraska ringnecks, knew the birds would tend to stick tighter as

Again, the line formed up and the group moved over to drive the other half of the field. This effort was more productive. Chris missed one rooster and then regained his reputation on a long shot. Dan almost stepped on a hiding rooster, whirled and dropped him within 20 yards when the bird swung behind the gunner.

The Columbus hunters take their pheasant hunting quite seriously. They visit with the landowners before the season opens for permission to hunt, which saves them wasting time getting permission at each new area. They also hunt many areas more than once and watch how the birds react when pushed out of the cover. In turn, they adjust their tactics to get the most shooting.

All five of the hunters use full-choke 12-gauge shotguns. Four of them shoot either No. 6's or No. 4's, but Chris shoots nothing but No. 2's. He claims the big shot breaks a bird down quicker and that he doesn't get a mouthful of shot every time he eats a bird.

How successful are these hunters? Fabulously, when you look at their records kept on birds bagged each year. Chris alone bagged 155 birds in 1965. The group had a total of 150 up to December 8, 1966, and felt they had some of their best shooting yet to come.

They are also well aware of bird populations and contend that there were just as many, if not a few more birds in their hunting area of Platte and Madison counties in 1966, than there had been in the past few years. This, in the face of some hunters complaining that bird populations dropped sharply in 1966.

From the brome patch, the group climbed into the car and headed west for another stop. This time their choice was a weed-filled creek bottom bordering a milo field.

Three men dropped off at one end, while the other two drove to the far end to block. Zigzagging, the drivers worked the cover slowly and when the 30-minute drive was over, they had added two more birds to the bag.

As mid-morning approached, they hunted a milo field, bagging a couple more roosters. At noon they switched again to the heavy stuff, knowing the birds had fed and would be in the heavy, loafing cover.

The groups hunting tactics are consistent with the harvest of crops, available cover, and weather conditions. Early in the season they like to hunt the cut milo fields. The birds are more widely dispersed and they get lots of shooting on singles and doubles.

As the corn is harvested and the frosts knock down some of the cover, the birds are gradually pushed into the heavier patches such as soil bank and creek bottoms. Pheasants also use shelterbelts during the day, so a belt was the next stop on the schedule of this well-drilled hunting team.

The average shelterbelt usually has little heavy ground cover, but the birds like the safety of the overhead tree growth and consistently frequent the areas. These belts are tough tests for a group of hunters, because the blockers must get into position without spooking the birds before the drivers are ready.

The Columbus hunters had hunted this belt before, so they dropped the drivers well out of sight of the birds. The two blockers then drove to the other end, quietly got out of the car, and moved into positions about 100 yards from the end. In thin ground cover birds will seldom run all the way to the end of the belt. One of the drivers went down the middle (Continued on page 64)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 15

RALLY 'ROUND THE JEEP

MOUNTAIN CLIMBERS scale peaks because they are there and swimmers take on the English Channel because it is a challenge. But what motivates a person who enjoys bouncing along in a jeep in the roadless back-country of Nebraska? Love of adventure and a sense of mastery over machines and terrain seem to be prime reasons.

The organized sport of jeeping is new in Nebraska, and when Don Dahlinger of North Platte, president of the Nebraska Ruff Riders, headquartered there, invited me to the organization's weekend campout, trail ride, and rally at the Valley View Guest Ranch, south of Maxwell, I had visions of hot-rodding kids. Instead, I met several family groups. My immediate impression was that these were grandpa drivers who wouldn't shift out of first, much less second. They soon changed my mind.

Billowy clouds backdropped the rolling hills as Charlie Easton, also of North Platte, guided our multicolored jeep caravan through narrow valleys to a campground in a bottleneck canyon. A tree-covered hill to the south and a high, barren ridge protected the camp site from the gusty wind.

Our first excitement began when Charlie spotted a lone outrider racing for camp. A two-wheel trailer had slipped off a jeep's hitch and tipped over. Charlie signaled the group to saddle up. Three jeeps with three riders each churned toward the accident. No one was hurt, but as we righted the camper, tinkling glass told of interior damage. Bedding, popcorn, and food scattered inside the trailer made a tossed salad mess, but everyone pitched in to clean it up.

After the ride back, Dahlinger explained that a good jeeper is one who keeps his vehicle in top shape and operates it safely. A driver must be familiar with the gear-lever positions in low and high range and know both the capabilities and limitations of his vehicle. Club members have had some squeakers, but there have been no serious accidents.

With camp established and supper an hour away, Don fired up his jeep and invited other members to tag along on a late-afternoon trail ride. I decided to ride with Doug Todd, who owns the only Bronco in the club. All other members own jeeps, most of them of 1947 and '48 vintages. For the most part, the four-wheelers were ready for the bone pile when they were first acquired, but hours of work put them in top condition. Some members have even added a touch of luxury to their rigs with padded upholstery.

As we bounced up the first hill, Doug said his four-wheeler lacked some of the maneuverability of the smaller and narrower jeeps, but he claimed it could go anywhere they could go. After we topped a high summit, Don in the lead rig pointed to an even higher ridge. A washed-out road, that looked like a dried-out creek bed, was the only way up. Halfway up, a barbed-wire gate stopped us momentarily. As Don put his jeep in gear, the trail-climber sputtered and for an instant looked as if his ride was over. Then the tires bit in solidly and the four-wheeler gained momentum as it moved upward.

From the top we could see for miles. Here, Indians might have watched pioneers following the nearby Platte River, or the railroad inching across the plains. Although the view was wonderful, our stomachs were growling for dinner so we backtracked for camp.

As the hills cuddled the sun and darkness sprinkled the sky with stars, the campers huddled around a shimmering fire. In cowboy country, only western songs seemed appropriate, and as strains of Red River Valley and Sioux City Sue drifted through the historic hills, a part of Nebraska's past lived again. Near midnight, distant thunder promised to settle the dust for the family trail ride and rally the next morning.

The next morning, Lyle Ross, host at the guest ranch, acted as guide as our nine-jeep caravan wound across country to the site of an original sod house. There were hills to climb, but that wasn't the major objective of this ride. Not entirely a thrill-seeking club, the Ruff Riders' purpose is to combine the unique go-anywhere quality of the jeep with activities that will be both educational as well as recreational for the whole family. Lester Drake, who helped build the soddie in 1904, conducted a tour of the house and told the children how it was built.

From the soddie, we headed toward a log house built in 1864 or 1865. Although remodeled into a farm house, the log home was once a stagecoach stop and then later a headquarters for railroad construction. Timbers from the valley were used to build the house and for railroad ties. It is evident that members of the Ruff Riders are becoming more knowledgeable Nebraskans because of their tours. The trip over we headed for camp where Don, Roland Elhston, and I set up a rally course.

In a rally, flags are placed in several hard-to-get-to spots and a map showing their locations is drawn. The winner is determined not by the fastest time, but by the driver who is the closest to the average time it takes to cover the course. Average time is figured by taking the times of all contestants and striking a mean.

Bob Dahlgren pulled to the line and with the starter's go his jeep seemed to rear back on its wheels before shooting forward. Bob had 12 flags to find, and he wasn't going to waste any time.

As Don Gollihare revved his four-wheeler, I hopped into the back seat as a non-committal passenger. I knew how to get to the flags, but it was going to take an awfully big bump to pry the information *out of me. Half the challenge of any rally is finding a way to reach the pennants.

Don had little trouble spotting the first banner, but Bob, who had a three-minute head start, was scouring the wrong ridge 100 yards down the valley. My driver shoved the jeep into low range and as the four-wheeler nosed up the slope all I could see from the backseat was blue sky ahead and bone-breaking ground behind. Bob, seeing his error, wheeled up the incline to join us. Six other flags were on the same hill, but higher up.

As the two hill climbers clambered up the slope to the second marker, Bob gained an advantage and churned into the lead. Giving up the front is bad enough, but eating the leader's dust is even more unbearable.

Evidently, Don felt the same way. He bounced into the lead as we headed for the third marker on the opposite side of a depression that looked like an inverted camel's hump. The only way down was to hang a sharp right at the edge of a drop-off that led to the valley floor and inch the bump buggy down the slope.

Don shoved the accelerator nearly to the floor as we hit the bottom of the ravine. The ejection seat in James Bond's fabulous car couldn't have thrown me any higher as we hit a hole, but my troubles were minor. Ten yards from the top the jeep sputtered and died. As Don backed down the incline, Bob gunned his four-wheeler and cruised by us, leaving a lot of that's-how-it's-done dust behind.

Don made like an army jeep driver caught behind enemy lines as he stormed (Continued on page 64)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 19

TREATY AT HORSE CREEK

by Warren SpencerNOTHING MOVED on the sweeping plain except the trickle of the tiny stream and the rivulets of blood that ran to meet it. The screams of the Sioux raiding party died away and the settlers' rifles were silent. An ironical quiet lay over Horse Creek, a place that had once been dedicated to an ever-lasting peace.

Fourteen years earlier, on the same ground that now ran red with settlers' blood, the Sioux and their brothers had pledged peace with the whites. For the first time in western history here was a treaty with teeth. It meant the beginning of a new life on the prairie, a chance for whites to build and develop the land —unmolested. At the time, the Indians wrere willing to go along with the proposal, too.

The whole thing began early in 1850. Under the leadership of Col. D. D. Mitchell, commandant of Fort Laramie, runners were dispatched to tell the tribes of a meeting scheduled for late the following summer. For almost a year, the messengers issued invitations, pleaded, cajoled, and ordered until they were assured that each tribe would send representatives. None of the Indians knew why they were summoned, and most thought it impossible that all could meet in peace, but they were willing to give it a try.

Colonel Mitchell and his superiors had a plan that had never been tried before. Not only did they want a peace padt between the United States and the Indian nations they also hoped to talk the red men into signing individual treaties aifrong themselves. But there was an element of the unknown in the idea. Would it work?

By mid-summer 1851, the Indian population between the Missouri River (Continued on page 63)

Largest council in Indian history met to cement lasting peace. Ironically, it was but a prelude to bloodiest wars

BEAR HUNTS DEER

Even dean of archers gets buck fever when tackling Nebraska's whitetails by Gene HornbeckTHE LATE-FALL sun sparkled brilliantly in the southern sky, flooding the rugged hills of northern Keya Paha County. Far below us, the Niobrara River glistened, reflecting a cloudless canopy of blue.

A gentle northwest wind moved the grasses of the hills as the two of us, crouching, stalked toward the top of a knoll. Waiting just beyond the rim was a mule deer doe, alert to the danger she sensed, but couldn't see. Her tail flashed as she stamped, looking nervously toward a sound that her ears had picked up.

Only 20 yards separated us when I nocked an arrow and raised carefully to a standing position. The deer and I saw each other almost instantly. Her ears snapped forward and her nostrils flared as she froze, staling; at me.

I could see only her head and neck and as I eased w*upward for the draw, she snorted. The limbs of the bd^ began a slow bend as I drew the string with its feathered shaft to my cheek. A twang sent the shaft in a-silvery blur toward its target. The doe whirled to escape, but the arrow met her before she made her move.

"Hit her!" I blurted loudly. "First time I have shot ra deer in a dozen years, and I scored."

"O.K., Robin Hood," my partner said, grinning at my excitement. "Let's ease up over the hill and see how far she went."

With the target I had and with any kind of a hit, she shouldn't go far," I answered, nocking another arrow.

"Never know till we check," Fred offered. "In bow hunting anything can happen and usually does."

My hunting partner and tutor was that grand old man of archery, Fred Bear. His hunting prowess and skill with a bow have gained him worldwide recognition few trophies in the big-game world have escaped him He has stalked and bagged lion and elephant in Africa, kodiak and polar bears in Alaska, moose and sheep in Canada, and antelope, elk, deer, black bear coyote, and other game in the United States.

A superb hunter, Fred also ramrods his archery company in Grayling, Michigan. Fred's own hunting experiences and constant use of the bow have made Bear Archery a leader in the field and done much to opuf arise the sport of bow hunting.

Topping the rise, we looked down into a brushy draw. There standing along the edge of sumac was my deer apparently ready to topple.

"Should I shoot again?" I questioned.

"I can't see her head," Fred answered, "but with the target you had I would say she'll drop any second."

We watched the deer until she staggered out of sight into the draw.

Just give her a little more time, Gene," Fred

coached. "Then we'll go into the thicket after her. She

SEPTEMBER, 1967

23

couldn't have gone far after a shot like the one you

just had."

couldn't have gone far after a shot like the one you

just had."

A couple minutes ticked off, so I suggested we check to see if there were evidence of a hit. A quick look revealed a large clump of hair, but no blood trail leading toward the thicket.

"Can't quite understand it," Fred noted, "but let's check where she was standing. There has to be blood."

"Hey, look," I stammered. "Is that my deer going up the other side of the draw?"

"Looks like the same one," Fred said, putting the glasses on the doe as she stood 100 yards away, switching her tail at us. "She still acts wobbly, but she isn't bleeding anyplace around the neck. Let's look for the arrow and blood here."

A quick search revealed no blood, but I did find my arrow buried in the sand at the edge of the thicket.

"No blood," I said, examining the shaft. "The insert is gone, but this arrow didn't go through the deer."

After some five minutes of deliberation, we walked through the thicket in time to see my deer bouncing merrily over the distant hilltop.

We weren't sure just what happened, but from the wad of hair, no blood, and the flight line of the arrow, we concluded that the shaft must have grazed the doe across the back of the skull, temporarily stunning her. All I had was a big clump of hair to show for my first shot at a deer in 12 years.

This wasn't Fred's first trip to Nebraska. He has hunted here three times before and has racked up a good mule buck and the best whitetail he has killed anywhere, a nice four-point, (western count). This time, he was trying for another big whitetail in the hills and bottoms along the Niobrara River, north of Bassett.

I got my shot on the second day of our hunt after a luckless first day that was more of a get-acquainted session than an actual hunt. We planned to hunt from a stand during the first couple hours of the morning and then drive the canyons that run off from the river bottom. We intended to return to our stands a couple hours before dark and wait for the deer to come to us.

Some previous scouting on the part of Dick Mauch, Bear sales representative, and Nick Lyman of the Nebraska Game Commission, both of Bassett, had set us up with a couple of tree stands along the edge of a cane field that deer were using. The rifle deer season had just ended, but Dick assured us there were still plenty of big whitetails.

He joined us shortly after my episode with the doe, unpacked a very welcome lunch, and listened to my tale of woe.

"Well, Gene, if you would have bagged that doe you wouldn't have a chance at those big bucks down along the cane field tonight," Dick said, sipping a shot of hot coffee.

"Bucks or does," I offered, "it doesn't make any difference to me, I'm going to shoot at anything I get a chance at."

"Practice time," Fred suggested, digging a couple blunts out of his bow quiver. The range was made to order as we were resting along a bale field. Leveling off on a bale, 30 yards away, Fred sent his first arrow into it, 5 inches off dead center. His next shot was right down the middle.

Fred is not an average bow hunter. He is at an age where most men are retiring, but he's lean and in better shape than most high schoolers. His felt hat, always cocked a little to one side, is a trademark with him.

"Just got used to wearing it," he states. "The soft brim bends when I draw the string back and it gives me good protection from the sun and it has become a good-luck charm."

Fred's bow was a 65-pound-pull, 60-inch tested killer. He is left-handed, uses a two-finger draw, and shoots with the bow canted quite a bit to the left. His stance is much like that of a trapshooter with his weight forward on his right foot. He was shooting aluminum arrows, with 125-grain razor-head points.

I was using one of his 48-inch recurved bows that was rated at 45 pounds on a 28-inch arrow, but my draw is 31 inches, and Fred informed me that the little hunting bow pulled about 3 pounds to the inch over 28, so I was pulling about 54 pounds.

After our practice session, we made a drive on a big canyon that cut toward the tableland, a mile from the river. Dick and I made the push with Fred taking a stand two-thirds of the way down the canyon. A pair of mule does cut around me and headed for the top rather than going down the draw, a typical reaction of mule deer. Halfway down the mile-long drive, I saw the flashes of whitetail flags as two deer spooked ahead of me. After meeting Fred at the end of the drive, he informed us that they were both does and had passed within a few yards of him.

By 3 p.m., the sky began to cloud over and the wind, carrying a hint of snow, picked up. Fred and I headed for our tree stands, while Dick picked a blind along the edge of an alfalfa field. I slipped on an extra 24 NEBRASKAland insulated jacket before climbing into the fork of a huge old oak. Then I settled down for what could be a long wait.

My stand was at the bottom of a small hill. To my left was pasture, while scrub oak, cottonwood, elm, and cedar covered the hillside —cover that whitetails like. Behind me was the big cane patch where we had seen lots of sign. My perch overlooked one runway coming along the fence line and two from the hillside where Fred had his stand. To my right across a 30-yard flat, the wooded hill climbed steeply for 50 yards before the trees gave way to short-grass hills.

Fred's stand overlooked two runways that came from the hills —one of them running right under his stand. Both of us were about 15 feet off the ground. Settling down on my perch, I removed the bow quiver and hooked it on a limb within easy reach, nocked an arrow, and settled back to wait for a deer. I could see Fred hunkered against the main trunk of his tree for wind protection. His stand was about 100 yards away.

We had been in the trees for almost an hour when I heard a deer snort and the cane crackle like a truck was going through it. Swinging quickly, I was just in time to see a huge whitetail with pieces of cane draped on his antlers come bounding out of the patch and head up the hill toward Fred.

The big buck slowed as he reached the cedars along the hill, a hundred yards west of Fred. The deer had evidently bedded in the cane patch and something had spooked him toward us.

Glancing at Fred, I could see that he was aware of the buck's position. A few moments later we heard the whitetail blow again. Somehow, he had picked up the scent of the hunter, but he wasn't sure of the position and was testing the airways for the source of the danger.

A fox squirrel chattered at me as I swung into shooting position, facing the direction of the buck. If he came, I wanted to be ready. The woods became silent again, except for the wind rustling through the trees. Five minutes stretched to 30 and I noticed that my leg had gone to sleep. The light was edging toward darkness, with still no sign of the buck, but we waited out the full 30 minutes after sundown and the close of legal shooting time. Finally, we crawled out of the trees.

"Did you see that rack?" I asked.

"Not bad," Fred replied, "I just caught a glance as he went into the cedars. Was that cane on his rack?"

"It was," I answered. "He must have been in an awful hurry to leave that patch."

"Maybe tomorrow he'll make a mistake, but right now I'm for a shot of hot coffee," Fred offered.

The following morning before light we were in the tree stands, but our stay was uneventful, except for a pair of does that came by Fred.

Later that day we saw two big whitetail bucks that we pushed out on a drive, but they weren't in range. Three does came bounding up to me and stopped within a few feet, but I was on the opposite side of a tree and when I turned, they vaulted a Slowdown and were gone.

Late in the afternoon on our last drive, Fred had a quick shot at a bobcat that was ghosting through some brush, but the arrow was deflected. The bob bounded away, wiser to the ways of the hunter.

The weather was meaner that evening as we climbed into our tree stands. A growing wind filled the woods with noise and since the temperature had dropped to the low 20's, my perch was like an iceberg. After an uneventful hour, I dropped to the ground and found a sheltered spot in some cedars along a runway to wait out the rest of the (Continued on page 59)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 25

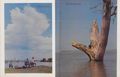

WATER WONDER

MILLIONS OF YEARS AGO when Nebraska was covered by a great inland sea, there was 1 not a blade of grass nor a kernel of corn to provide sustenance for life. The sea was then the great provider, the giver of life.

Gradually the waters subsided, giving way to land. Still, water held an omnipotent power over living things, for without water there would be no blade of grass or kernel of corn. Water was the magnificent benefactor that lent greenness to the fields and freshness to the flower.

Even though the giver of life, water has its own identity. Ever moving, ever changing, it knows no single mood, no single personality. Water can be as black as night or blinding as sunlight's glare. Sometimes as quiet as the lull before the storm, it can be as angry as the storm itself. Nebraska's water is water of many moods. Typical of the state's ever-changing water is Harlan County Reservoir, 17,100 acres of personality.

The most southern body of water in Nebraska, Harlan County Reservoir can be as gracious and gentle as a Southern Belle, although she is Amazonian in size. Sitting pompous and proud in a glimmering costume of silver and blue, the pride of Harlan County wears windblown waves for laces and white-frosted sailboats for brooches. Like a gracious mother patiently attending a demanding child, so does Harlan County Reservoir serve hundreds of fishermen. Her fertile waters guard their treasures well but without jealousy, and give up their goods because their store is great.

26 NEBRASKAland

From the beginning of time, water has traveled a natural cycle from ocean to cloud, to land, to stream, to inland sea, and then again a part of a great ocean.

The water at Harlan County Reservoir is oblivious to its part in this cycle. Droplets of rain forming ringlets upon the water are soon swallowed up by the bigger body, just as bass swallow up minnows. In a moment, the ringlet is gone, lost forever as if it had never been. As rain creates a hazy mist over the horizon, everything moving disappears from the surface of the water. Only the fish are left as the sportsman in his sailboat and the fisherman in his johnboat scurry to shelter. The sky bends low to the water, joining to create a scene of gray— quiet and moody.

After the rain has spent its fury, surface life returns. The haze lifts and the water takes on fresh activity as sailing man and angler return. Along the shores, flowers of pale yellow and rose-red revive as the sun changes hazy gray to shimmering silver. Once again, all is quiet, calm, and peaceful, the water as translucent as a crystal.

The dam, stretching for more than a mile across the reservoir, is the gateway to a different mood. Below the spillway, the water is a roiling, swirling mass, indignant at having been tossed out of the reservoir. Just below the spillway it spends its vengeance, alone in sorrow, before continuing on its bruised and angry journey down the Republican River.

Just as a woman changes her costume to suit the season, so does Nebraska's water adopt new appearances and moods throughout the year. In winter, it becomes stern and impassive, waiting for the magic of winter sun and frigid air to transform it into a sheet of silvery ice.

Harlan County Reservoir is slow to warm to Nebraska's sun. She takes her time before welcoming swimmers and picnickers to her shores. But once she feels and accepts the power of the sun she quickens her pace and joins the fun with gay abandon.

Harlan County Reservoir has a personality which waits to be discovered anew each visit. She was created by man and serves him well, but Harlan is still water with all its moods, all its faults, and all its appeal. In the final analysis, Harlan Reservoir is a companion, an accomplice, and a partner to man and his pleasures, but never an inferior.

THE END 32 NEBRASKAland

SIGHTS ON GROUSE AND QUAIL

Feathered deception, these birds can give even the saltiest of scattergunners shooting fitsONE OF THE smallest, but strongest contributors to NEBRASKAland's reputation as the nation's mixed-bag hunting capital is the bobwhite. Ornothologists say the bobwhite is not a quail at all. Rather, they insist, he is strictly an American specimen. But the sportsman is concerned with his game aspects, so bobwhite's official lineage is unimportant. How and where to hunt him, however, are. This rundown may help you.

Where can I find quail? Though Nebraska is near the northern and western limits of the bird's range, quail can be found throughout the state, primarily along river systems and where woody cover is adequate, except in the Sand Hills.

Are bob whites abundant here? Quail are plentiful and are extending beyond normally established ranges. A mild winter contributed to their overall well-being. Last year's quail season was one of the best.

Are bobwhites easy to find? They will occasionally be found in pheasant cover, but usually they like brush, edge, and short grass rather than heavily weeded areas. The little critters can be found in ground cover that hardly seems capable of hiding a grasshopper. Available water is often a tipoff to the possible presence of quail. As cold weather approaches, they seek heavier cover and move less. In bad weather, they may feed only once a day.

What are recommended hunting methods? Many gunners find bobwhites too elusive to knock down with any regularity. Beginners normally "flock shoot" and rarely get results. It takes control and experience before a quail hunter realizes he must pick out one bird and concentrate on him. A covey will normally scatter, but none of the members journey far, and singles can be jumped once again within a short distance. Quail will stay where they land, but are stubborn about getting up the second time. If 20 birds from a covey land in short grass, a hunter can do everything short of bulldozing the area and still not all of the birds will get up.

What are the best shooting hours? Bobwhites follow rigid routines, giving the hunter a fairly logical pattern to follow. Best hunting can be found after birds have moved to loafing areas from about two hours after sunrise to two hours before sunset.

Is a dog essential? A dog is recommended for working singles and recovering cripples. Quail are a Natural" for a dog. Coveys provide ideal pointing targets. Moving quail coveys leave a scent for a dog. Pointers are a joy to watch while working with quail, but good retrievers are probably more important than pointers. Downed birds are easily lost and a hunter without a dog is at a disadvantage.

Are there any special problems with a dog? Hunters should provide boots for their dogs since some good quail areas are infested with sandburs.

What are the season lengths and the various limits? Last year's daily quail bag limit was 6 with a possession limit of 18. This year's daily and possession limits and season lengths will be set after field surveys are completed. The 1967 opening date of November 10, however, has already been announced.

What about guns and shot sizes? A light, short-barreled gun that comes up fast and swings easily is just the ticket for bobwhites. Quail shooting requires a shot pattern that is relatively "wide" at close range, with Nos. 7 1/2, 8, or even 9 recommended. A modified or improved-cylinder bore will work best, as most shooting is within 30 yards. The 20-gauge is most popular with dyed-in-the-wool bobwhite hunters, but 16 and 12 gauges are also used.

What the Sand Hills lack in quail, they make up in prairie grouse, a general term that includes both sharp-tailed and pinnated grouse or prairie chicken.

What's the difference? Sharptails are easy (Continued on page 60)

FOCUS ON PHEASANTS

There's no question that ringnecks rule the hunting roost. But these answers may help you to dethrone himHOW WOULD YOU like to see a solid line of rooster pheasants, beak to tail, from Omaha to Scottsbluff and back to North Platte? That's a lot of birds, but that's how many roosters NEBRASKAland hunters bagged during the 1966 season. The estimated take was 1 1/4 million birds during the 93-day season that began in late October and ended in late January. Figuring the average rooster at 30 inches from beak to tail, this harvest, if laid end to end, would stretch 591 miles. Since Nebraska had a short hen season, you can add a few miles of drabies to make up for detours, rest stops, and wrong turns.

A good start on this colorful trail was made during the first two weekends of the season. Even so, hunters didn't get any lucky breaks. The early days were hot, dry, and windy, three conditions that are not conducive to easy hunting. To make matters worse, farmers were late with their harvests and some prime land was closed to prevent damage.

Where did the hunters find their targets? Top producers were corn, wheat, and milo fields, weedy draws, dry-creek bottoms, patches of plum brush, grassy areas, and "dirty" fencerows. Hunters in the wheat country of southwest Nebraska found birds in the stubble but getting within gun shot of them wasn't easy. As the season wore on and the cover decreased, the birds bunched up in draws, brush, and fencerows. Roosting areas of goldenrod, ragweed, matted grass, and cane patches were worth early-morning and late-afternoon passes. Corn and milo fields were good for mid-morning and afternoon hunts while weedy areas were pretty good for middle-of-the-day gunning. Cold and snow tend to huddle birds in the shelterbelts and hunters who knew how to hunt these spots got shooting.

How are these various areas hunted? Some hunters use the block-and-drive method in the big fields. A party divides into walkers or drivers and waiters or blockers. The foot sloggers course through the corn and milo fields at 15 to 25-yard intervals with the side men slightly ahead of the down-the-middle drivers. Blockers wait at the end of the field. Both groups may get shooting. Young and inexperienced cocks often flush in front of the walkers while older and wiser birds leg it ahead until they run out of cover and have to fly, giving the blockers their chance. Huge fields take two or three passes for complete coverage.

How about the loner? Does he have a chance? The lone shooter has it tougher, but the step, step, stop method works well in smaller patches of cover. Old John Ringneck is pretty cagey, but he is also the nervous type. Hell sit tight if he hears the hunter moving, but if his pursuer stops after a few steps, the rooster figures he's spotted and will break — sometimes.

What about shelterbelt hunting? This takes at least two hunters to be effective and four or six are better. This hunting is very similar to the block-and-drive, but on a smaller scale. One team of hunters pushes through the trees, driving the birds toward the blockers. A flanker on each side of the belt can stop the birds that leak out from the drivers.

What about one-man, one-dog hunting? It isn't the easiest way in the world to hunt pheasants, but it is far better than the one-man attempt, especially if the hunter sticks to the relatively small covers. If the dog hasn't got aspirations to be a Kentucky Derby entrant and ranges close to his boss, the hunter will get good shooting. Normally, pheasants do not hold well to a dog and a "big" running canine can spook birds into the next county before the hunter ever gets in range.

Is a dog a must? No, but he is a great help if he is well-trained and easy to control. However, many hunters do very well on their own. A dog is of inestimable value in recovering cripples.

What are the requirements for bringing a dog into Nebraska? All dogs brought into this state must have a health certificate attesting to his freedom from disease and his immunization against rabies, plus a description of the animal.

How about places to hunt? A hunter must have permission to hunt on private property. However, land in the Crop Adjustment Program (CAP), identified by a green and white sign with the legend, CAP FARM, Public Access, is open to public hunting without requiring permission. There are also numerous state and federal areas open. See the Where-to-Hunt listing elsewhere in this magazine.

Will last year's techniques work this year? Yes. Pheasants are creatures of habit and follow rather rigid preferences for roosting, eating, and resting areas. Unless there has been significant changes in habitat, the birds will generly occupy the same areas year after year. However, you may find that you will have to shift your hunting area to find the birds. Subtle changes in habitat can occur which will not be noticed by the hunter but which are important to the well-being of the pheasant.

Where are all the pheasants? Nebraska's conservation officers hear this question in their sleep. Pheasants are scattered state-wide, with the exception of the Sand Hills area in north-central Nebraska. Concentrations vary, depending upon habitat and local climatic and agricultural influences. The accompanying map shows the pheasant range in Nebraska.

Is a guide required? No. Many Nebraskans offer guide service and accommodations during the hunting season for nominal fees, but guides are not required. Strangers, hunting Nebraska for the first time, will undoubtedly do better if they have someone "show them the ropes".

How much is a nonresident license? Such a license to hunt all upland game and waterfowl is $20 plus a $1 game-bird stamp. Licenses are available from vendors, the Game Commission's District Offices, and the Nebraska Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, and by mail by sending all of the essential information and remittance to the last mentioned office. Licenses do not require advance application and can be obtained after arrival in the state. No restrictions are placed on the number of nonresident permits. All nonresidents, regardless of age, must purchase a nonresident hunting permit and stamp to hunt in (Continued on page 61)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 39

ON TARGET FOR WATERFOWL

Nebraska's webfeet run the gamut—tiny teal to heavy honkersWATERFOWL HUNTERS are a rare breed. Who else would sit in a blind in sub-zero weather waiting for a target to fly by? And what other sportsmen would belly across 2 miles of frozen Nebraska landscape for at best a 50-50 chance at a feeding honker? Yet, this is what thousands of Nebraska and out-of-state hunters do each year as they take a crack at the cream of Central Flyway shooting. Judging from the 270,444 waterfowl taken in NEBRASKAland during 1966, their madness pays off.

What species are available? Nebraska boasts both puddlers and divers, ranging from mallards to mergansers. The state has at least a flirting acquaintance with some 26 varieties. Five members of the goose family are taken here. Blue, snow, and white-fronted geese are in the majority. The large or Common Canada is the trophy bird of the clan. Smallest of the Canadas is the Hutchins's followed by the Lesser Canada.

Where did the hunters find their targets? During the early part of the season, small ponds and sloughs were ideal. Later, as new migrants moved into the state, large impoundments became prime areas. For field-feeding ducks and the majority of geese, corn, wheat, and milo fields were high-kill areas. Migratory birds were where you found them, regardless of species.

How are these various areas hunted? While many gunners build camouflaged blinds along shallow waters, jump shooting is the most popular here. Hunters move from pond to pond, trying for feeding or resting ducks. Diving ducks call for blind hunting on a larger scale. Decoys, deployed to attract targets, are used. Geese, on the other hand, are often found in fields and are taken by sneak hunting. In this method a hunter creeps as close to a feeding flock as possible. Pits are also used for geese. These are built in fields, then camouflaged to resemble the surroundings. Decoys add to the pit setup.

How about the loner? While duck hunting works for the lone hunter, 40 NEBRASKAland a group is often better. The ideal partner is a dog. Since most kills land in the water, a canine sidekick is worth his weight in gold for retrieving. Geese are probably easiest for the loner, since he seldom must retrieve a floating target. The birds' dry-land habits make them easier to drop on solid ground.

Is a dog a must? No. Many waterfowl gunners get along just fine by using fishing rods and weighted lines for retrievers. However, this technique is confined to smaller bodies of water and will not work on lakes or large rivers. Another idea is to use an inflated rubber doughnut to chase down kills.

When is the best time to hunt? Migrating waterfowl reach peak numbers during the second and third weeks of October. Puddlers comprise the majority of the ducks, but divers are well represented after midmonth. In late October or early November, Nebraska's wintering population moves in. This flight creates the state's best mallard gunning. Nebraska has a September teal season which is open for holders of special permits. Snow and blue geese move into the state between October 1 and 20. White-fronted geese arrive from the 5th to the 15th. A western influx of Canadas arrives around November 7 or 10. The first major storm of the season drives laggard migrants across the state, creating a renewed flurry of gunning.

How about places to hunt? Unless specifically marked as open hunting areas, all wetlands must be considered private property. Hunters must check with the landowners prior to entry. See Where-to-Hunt listing for public hunting areas.

Will last year's hunting techniques work this year? Yes, Resident waterfowl establish regular feeding traits. Sunrise and sunset schedules parallel each other from year to year and choice times of the day last year will be equally good in 1967. Migrating waterfowl are more sporadic, lunching and resting when the mood strikes, rather than on schedule.

Where are all the waterfowl? Ducks and geese are found statewide in wetland areas. Geese frequent drier areas and are usually within easy range of water. An early goose flight crosses the eastern half of the state while another covers the western half a little later. The latter supplies resident wintering populations along the Platte River. An oblong area stretching along Nebraska's northern border around Niobrara also supports good gunning after midseason.

Is a guide required? Many Nebraskans offer guide services and accommodations throughout the season, but guides are not required. Nonresidents and strangers to an area may wish to hire a guide to familiarize them with the terrain.

How much is a nonresident permit? $20. This permit is good for the calendar year and must be renewed after December 31. In addition, a federal waterfowl stamp is required. It is valid from June 1 to May 31 of the following year.

What are the 1967 season lengths and limits? These were not set at the time this issue went to press. State seasons are established within a federal framework for the Central Flyway.

Can anything besides waterfowl be hunted? The (Continued on page 54)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 41

CROSS HAIRS ON BIG and SMALL GAME

There are many ways to hunt them, but no method is easy. Knowledge of quarry's habits will give shooter slight edgeTHERE ARE MORE deer and turkey in NEBRASKAland now than there were back in Indian days. This is hard to believe, especially when you consider that men, their major predators, were far and few between back then. Besides, yesterday's firearms were pretty sad compared to today's high-powered performers.

Let's look at Nebraska's big and small-game pictures. In 1966, the rifle-deer success was 68 per cent, while slightly more than 8 out of 10 antelope hunters scored. Turkey nimrods chalked up a success score of 52 per cent.

Squirrel and rabbit hunters also had a popping good time. But game doesn't die of fright because you are carrying a firearm, so it isn't going to help if you don't know the how, when, and where of hunting in NEBRASKAland. The following may help you.

Where is the game found? Mule deer and antelope dwell in the wide-open, rugged sections of the state. Turkey stick closer to the wooded areas, with the Pine Ridge terrain considered typical cover. Whitetailed deer favor the state's brushy, wooded sections. Generally speaking, whitetails are found in eastern Nebraska while mule deer are in the west. However, there are overlaps of both species.

Canyons, ravines, and shelterbelts are good rabbit spots while wooded areas near corn, milo fields, and streams are natural hangouts for high-climbing squirrels.

How are these areas hunted? For mule deer and antelope a "tramp- the-hills" technique is standard. Since mule deer and antelope expe- ditions take planning, pre-season scouting is a great help. Sit and wait is recommended for white-tailed deer and turkeys. A properly operated call will give gobbler hopefuls an edge.

How about the individual hunter? Can he score? Big-game hunting is a sport for the individual. Since a troop of hunters can rattle a buck a mile away, the loner often has the best chance. This also holds true for turkey. In squirrel hunting, a partner may be handy to spook the bushytail to your side of the tree when he hides out. Bunnies may be hunted in groups using the drive method. This is often more productive than a do-it-yourself attempt.

How about places to hunt? Most big game and turkey are on private land and the hunter must obtain the landowner's permission. There are state and federal areas available, so check Where-to-Hunt listings elsewhere in this magazine.

Will last year's hunting techniques work again? Yes. Big and small game are creatures of habit. They do move, but, if they do, they usually frequent areas much the same as those they left. Natural or man-made changes in their habitats may result in an exodus. Hunting techniques will not vary much from year to year in similar terrain.

Are guides necessary and available? Hunters unfamiliar with the terrain and game habits will do better if they have a native helping them, but a guide is not a requirement for big-game hunting.

How much is a nonresident permit? Big-game hunters from outside Nebraska pay a $25 fee for each deer and antelope permit. There are no combination licenses, and the permit is only valid in the management unit for which it is issued. Turkey permits are $15. Permits are obtained through mail-only applications and hunters must be 16 or over. Some units permit a one or two-day, any-deer kill. Permits are valid for the current season only.

What's the procedure on bagged game? Most hunters prefer to field-dress their kills on the spot. Small-game hunters may want to carry an ice chest for transporting their take. Antelope require immediate field dressing, since their meat develops a musky taint if not properly cared for. Deer (Continued on page 55)

SEPTEMBER, 1967 43

WHERE TO HUNT STATE AND FEDERAL AREAS