NEBRASKAland

1967 Centennial Issue $1

As Nebraska Celebrates its 100th Birthday...

IT'S OUR BIRTHDAY TOO!

The organized independent insurance agents of Nebraska are celebrating their 60th year of service as an Association in 1967.—We are pleased to be celebrating our birthday with the wonderful Cornhusker State in its glorious Centennial year.

Your independent insurance agent is as typical Nebraska as corn, cattle, Sand Hills, and the unique brand of Nebraksa hospitality which has made us the outstanding State in the great United States of America!

OUR 60th BIRTHDAY Nebraska Association of Insurance AgentsStuart Building

Lincoln, Nebraska 68508

My best wishes to the citizens of Nebraska on the Centennial of a great state.

NEBRASKA CENTENNIAL PURPOSES

Five main goals will be met as we close one century, move confidently into nextNEBRASKA'S CENTENNIAL is both an ending and a beginning, the closing of one chapter and the opening of another. As Nebraskans celebrate 100 years of statehood, they stand at the crossroads of time. Behind us is a rich heritage and a century full of accomplishment. Ahead lies the limitless future.

If Nebraska's past could be summed up with one descriptive phrase, it would be "Taming of the Land". But that is behind us now and the future will not lend itself to such precise terminology. Yet, if there is an applicable term for what lies ahead, it could be: "Era of Challenge". During the next century, Nebraska and Nebraskans will face challenges as great or greater than any that have come before.

A commission has been formed to coordinate the state-wide observance of Nebraska's Centennial. Every community in the state has an invitation to participate in the celebration. All facets of Nebraska's culture are to be explored for centennial ideas and projects.

Since the Nebraska Centennial will receive national publicity, it will attract visitors from all over the United States and the world. Besides offering plenty of entertainment, the centennial will be enhancing Nebraska's over-all economy due to the influx of tourist dollars. A pamphlet, listing hundreds of possible centennial projects, will be available from the Centennial Commission.

And so, as Nebraska looks towards its second century, it is well to list the immediate and future objectives of our centennial observance. They are few in number, but important in scope.

1. To develop the appreciation by Nebraskans of the natural, cultural, spiritual, and material resources of the State of Nebraska.

2. To develop programs and projects which will be of lasting value to the State of Nebraska, during its second 100 years.

3. to involve all Nebraskans from every section of the state in preparing and presenting the many phases of the centennial celebration.

4. To stage a celebration of such magnitude as to attract the largest number of persons possible to the state and to its many recreational areas.

5. To present to the nation and to the world Nebraska's economic potential.

The first challenge of the new century is right here in these five objectives. There is no doubt that it will be more than met by all Nebraskans, for if there is anything that we love more than a celebration it is the challenge of making it a success. Before 1967 ends, the nation and the world will know Nebraska better than ever before.

THE ENDA CENTENNIAL MUST!

Travel Back To 1830 at... THE HAROLD WARP PIONEER VILLAGEI-80

U.S. 6

U.S. 34

NEB 10

HAROLD WARP PIONEER VILLAGE MINDEN, NEBRASKA

30,000 HISTORIC ITEMS IN 22 BUILDINGS

Adults—only $1.35 Minors 6 to 16—50¢ Little tots free

Stroll less than a mile and see 30,000 historic items housed in 22 buildings—many of them authentic pioneer Nebraska structures. Displays show every aspect of America's growth the last 137 years.

Easy to reach—just 130 miles west of Lincoln, Nebr.; 14 miles south of U.S. 30; 50 miles north of U.S. 36. I-80 travelers take Pioneer Village exit between Grand Island and Kearney, then drive south on Nebraska 10.

Open 7 a.m. to sundown every day. Modern 66-unit motel, restaurant, picnic and overnight camp grounds adjoining.

WRITE FOR FREE FOLDER!

ONE OF TOP 20 U.S. ATTRACTIONS

A Centennial Message from the Governor

The celebration of Nebraska's Centennial brings to mind a number of colorful images. Here in Nebraska we can look back into our history and see smoke rising from Indian campfires, or cavalry guidons moving out from frontier outposts, or gandy dancers laying out bright rails of steel across the prairie. Our pioneer heritage and the lore of the frontier hold a fascination for all of us, but we must also view the picture which the future spreads before us. We must seize the opportunities presented by the partnership of our agriculture and our industry, by the programs of our schools and colleges, and by the steady development of our natural resources for both commerce and recreation. We have as much to do, or more, as has already been done, and we must go forward with strength and vitality into our second century. The true meaning of our Centennial will be in our demonstration to all the world that "There is no place like Nebraska."

Norbert T. Tiemann

JANUARY Vol 45, No. 1 1967

CENTENNIAL ROUNDUP 9 WOULD YOU BELIEVE? 12 THE FIGHT TO BELONG 14 Warren Spencer PLAIN JIM... 20 Holly Spence BATTLE CRY OF THE PLAINS 22 J. Greg Smith THE BIG MEDICINE TRAIL 29 Bess E. Day THE MANY FACES OF MARKET HUNTING 34 Gene Hornbeck THE TALKING WIRE 38 Glenda Woltemath THEY GAVE OF THEMSELVES 42 Bob Snow 12,000 TIMES TO THE MILE 46 Fred Nelson "HEAD THEM UP" 52 Jack Pollock A PEOPLE'S PRIDE 56 Neale Copple and Emily E. Trickey "BLOW OUT" SPELLS RODEO 61 Kay Van Sickle FOR EACH HIS OWN.. AND 37 62 Ralston J. Graham TOWNS THE RIVER BUILT 66 John Sanders ODE TO NEBRASKA 70 Elizabeth Huff HUNTING IN A HURRYING WORLD 81 Lloyd Vance THE GOOD "NEW" DAYS 84 Glen FosterNEBRASKAland

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS EDITOR, DICK H. SCHAFFER Editorial Consultant, Gene Hornbeck Managing Editor, Fred Nelson Associate Editor: Bob Snow, Glenda Woltermath Art Director, Jack Curran Art Associate, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard Photogrpahy, Lou Ell, Chief; Charles Armstrong, Steve Katula, Allan M. Sicks Advertising Representative, Ed Cuddy Advertising Representatives: Harley L. Ward, Inc., 360 North Michigan Ave., Chicago, Ill. GMS Publications, 401 Finance Building, P.O. Box 722, Kansas City, Mo., Phone (816) GR 1-7337. DIRECTOR: M. O. Steen NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION AND PARKS COMMISSION: W. N. Neff, Fremont, Chairman; Rex Stotts, Cody, Vice Chairman; A. H. Story, Plainview; Martin Gavle, Scottsbluff; W. C. Kemptar, Ravenna; Charles E. Wright, McCook; M. M. Muncie, Plattsmouth. OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland, published monthly by the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission, 50 cents per copy. Subscription rates: $3 for one year, $5 for two years. Send subscriptions to OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska 68509. Copyright Nebraska Game, FOrestation and Parks Commission, 1966. All rights reserved. Second-class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska and at additional mailing offices.

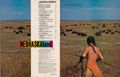

Since January launches the Centennial Year for all Nebraskans, it seems only appropriate that this year's first Hostess of the Month is NEBRASKAland Queen, Patricia Knippelmier. This petite, five-foot, five-inch, brown-haired beauty was chosen NEBRASKAland Queen from among 12 college queen candidates. Miss Knippelmier invites her fellow Nebraskans to participate in Centennial activities and to make 1967 rich with accomplishments and great with promise. Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Rudolph Knippelmier of Auburn, she is Peru State Teacher's College Sweetheart. Patricia was chosen Homecoming Attendant in 1964 and 1965, and has served as cheerleader for two years. She was elected the Best-Dressed-Girl on the campus in 1966. And is a member of Kappa Delta Pi, national educational honorary, The NEBRASKAland Queen is a senior, majoring in elementary educaiton. An accomplished musician, she plays the piano and clarinet.

CENTENNIAL Roundup

Call it tribute to pioneers, or start of another century of challenge, 1967 will be a year of gala celebrationsA YEAR TO remember—1967—will glow with festivals, pageants, shows, and extravaganzas all across NEBRASKAland. Commemorating her 100th birthday as a state, Nebraska will be decked out in full regalia from border to border to celebrate the Centennial in grand style.

Contests, exhibitions, adn local festivities galore will ring in the second century of progress and prosperity to NEBRASKAland.

January gets off to a fancy start. The U.S. Figure Skating Championships will be held at the Ak-Sar-Ben Coliseum at Omaha, January 18 through 21. From then on concerts, shows, tournaments, plays, musicals, barbecues, expositions, horse racing, circuses, Indian dances, picnics, fiddling contests, trail drives, and rodeos let looe for an events-filled 12 months.

NEBRASKAland DAYS with all its colorful pageantry highlights summer activities in July. This rip-snorting extravaganza combines the best of Nebraska for a fun-filled week of excitement, parades, rodeo, powwows, contests, and celebrities.

August simmers with the Sixth Annual Nebraska Czech Festivals at Wilber, the Second Annual Neihardt Day and "Black Elk Speaks" Pageant at Bancroft, the Country Music Contest at Brownville, and Nebraska's Big Rodeo at Burwell.

Topping the calendar for September is the Nebraska State Fair at Lincoln, September 1 through 7. From then on the pace never slackens. The Powwow National Congress of American Indians will meet at Omaha, September 18 through 23, and the Ak-Sar-Ben Championship Rodeo and LIvestock Show will open at Omaha on September 22 through 30.

Football fever spreads like a grass fire across NEBRASKAland, and hunting seasons open with a bang in October. Fall brims with rich hues and gala events in NEBRASKAland. From the Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation and Ball at Omaha, October 20 and 21, to fall festivals scattered throughout the state, Autumn glitters with thigns to do and places to see.

December winds up 12 months of NEBRASKAland activities, and brings the Centennial year to a close. One of the top-rated tourist attractions in the United States, the Christmas pageant at Minden to be held December 10 and 17, lures visitors by the thoursdans to witness the "Light of the World." Also on the holiday agenda will be the Christmas Diorama at Hemingford, December 1 through January 1.

Rich heritage, beauty, and pageantry are reflected by the many events and festivities planned throughout NEBRASKAland during 1967.

THE ENDWHAT TO DO

January1—New Year's Day 2—Opening of Legislature, Centennial Ceremony, Lincoln 6-7—Kearney State Invitational High School Debate Tourney, Kearney 10—Chamber Music Concert, Sheldon Art Gallery, Lincoln 17—Lincoln Symphony Concert featuring Leonard Rose, Lincoln 18-21—U.S. Figure-skating Championships, Ak-Sar-Ben Coliseum, Omaha 22-24—Midwest Spring Gift Show, Omaha January-May 5—Contest for typical centennial bride and groom planning June wedding

February2—Ground Hog Day 3-19—"A Streetcar Named Desire", Lincoln Community Playhouse, Lincoln 4—Nebraska Coed Follies, Lincoln 5—Boy Scout Week 11-14—Midwest Gift and Antique Show, Omaha 12—Lincoln's Birthday 14—Ice Capades, Lincoln 14—Valentine's Day 17-26—Sports, Vacation and Boat Show, Civic Auditorium, Omaha 20-24—World-Wide Misisonary Conference, Grace Vivle Institute, Omaha 20—Theodore Ullman, Pianist, Peru 27—Tri-County Centennial Pageant and Musical, Springview 28—Tri-County Centennial Pageant and Musical, Bassett

March1—Centennial Kick-Off, Statehood Day, and Unveiling of Commemorative Stamp, Pershing Auditorium, Lincoln 1—Opening of Old Pictures Show, Townsend Studio, all year, Lincoln 1—Tri-County Centennial Pageant and Musical, Ainsworth 1—Centennial Birthday Ball, Nelson 1—Webster County Historical Show, Red Cloud 1—Centennial Kick-Off Ceremonies, Statewide 3—Iowa State Singers Concert, Omaha 3-12—Musical Tours of State, Nebraska Wesleyan University, Lincoln 5—Centennial Religous Sunday, Statewide 6—"The Manager", Festival of Arts, Omaha 7—American Legion Talent Show, Stuart 7—Lincoln Symphony Concernt with Tenor Jess Thomas, Lincoln 9—"The Ballad of Baby Doe", Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha 9-10—State High School Basketball Tournament, Lincoln 16—Home, Sports and Travel Show, Pershing Auditorium, Lincoln 17—St. Patrick's Day Celebration, O'Neill 21-22—"A Century of Progress", Triumph of Agiruclture Exposition, Omaha 26—Easter 29-April 1—American Athletic Association of the Deaf Basketball Tournament, Omaha Hourse Racing, Fonner Park, Grand Island, late March

April1-5—Fine Arts Festival, Nebraska Wesleyan University, Lincoln 2—Square Dance Festival, Omaha 4—Lincoln Symphony Concert, Lincoln 5-15—National AAU Wrestling Championships, Lincoln 5—Midwestern Art Exhibit, Peru 8—Gala Festival, Union College, Lincoln 9—Mid-state Square Dance Festival, Comlumbus 13—National Oratorical Contest, Lincoln 18-19—Fourth Midwest Conference on World Affairs, Kearney 18-23—Ak-Sar-Ben Ice Follies, Omaha

For nearly 100 years Storz has been a Nebraska tradition.

Since 1876, the year when Storz began brewing an authentic Old World premium Pilsner, there have been many changes in Nebraska. But one thing that has remained the same is the Nebraska tradition of enjoying a light, bright Storz Beer. That's because Storz is the Nebraska beer. The beer that pours more pleasure. It's brewed right here in the heart of the Midlands and rushed to you at the peak of fresh, full flavor. Always fresh. Always refreshing. Why nto uncap a golden Storz right now and drink a toast to Nebraska's next 100 years? It's the local tradition.

20—Banquet honroing 100-year families, Lincoln 21-22—Boy Scout Centennial Circus, Lincoln

May1-November 1—Siouz Indian Village Opens, Red Cloud 4-6—State Industrial Education Fair, Kearney 5—May Fete, Peru 5-6—Health Fair, Nebraska Center, Lincoln 5-8—Art Show, Minden 5-21—"Fantasticks", Lincoln Community Playhouse, Lincoln 5-July 4—Horse Races, Omaha 6-7—Centennial Rabbit Show, Lincoln 6—Square Dance Festival, Lincoln 7—Armed Forces Week 13-20—Centennial Days, Omaha 22—Historical Society Dedication, Table Rock 25—Faith of Our Fathers Day, Keya Paha, Brown, and Rock counties 30—Memorial Day 31—Midstates Federation Track Meet, Cozad

June1-3—Gun, Coin and Antique Show, Columbus 2-3—Centennial Celebration, Rising City 2-4—Pioneer Memorial Tea, Barbecue and Pageant, Nelson 3—Lewis and Clark Epedition, Brownville 4—Third Annual Black Powder Shoot and Parade, Holbrook 5-July 7—Rodeo, O'Neill 5-12—Cadette Schouts Heritage Caravan Tours Nebraska 9-11—Centennial Celebration, Dodge 11-17—Rodeo, O'Neill 14—Re-dedication of State Capitol, Lincoln 16-18—Dodge County Centennial Celebration, Dodge 16-18—Centennial Celebration, Newman Grove 18-24—Homestead Days, Beatrice 19-23—National Young Republicans, Omaha 22-24—Swedish Festival, Stromsburg 22-25—Dakota County Centennial Pageant, South Sioux City 24-25—Centennial Celebration, Ulysses 24-25—State Sand Greens Golf Meet, Oshkosh 30-July 2—Czech Festival, Clarkson 30-July 4—Centennial Celebration, Superior

July2—Raft trip down Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, Omaha 2-7—Rodeo, Centennial Pageant and Exhibitions, Norfolk 3-4—Centennial Rodeo, Sutherland 3-4—Morrill County Amateur Rodeo and Celebration, Bridgeport 3-5—Centennial Celebration, Valentine 6—Horse Races, Lincoln 9—Quarter-horse Show, Stuart 1-—Old-fashioned Wheat Binding, Shocking and Threshing Bee, Syracuse 10-12—Centennial Celebration, Alexandria 11-12—Forty-Sixth Annual Annevar Celebration, Ravenna 12-14—Centennial Pageant, Battle Creek 14-15—LIttle Britches Rodeo, Chadron 16—Stock car races, Stuart 17—Indian Ceremonial, Hemingford 17-20—Golf and Tennis Tournament, Alliance 22-24—Southeast Nebraska Steam Threshing Bee and Antique Show, Table Rock 23—Century of History and Music, Pinewood Bowl, Lincoln 29—Summer Fun Festival, Harvard 29-30—Ash Hollow Pageant, base of Windlass Hill, Lewellen 30—Nebraska Grange Centennial Celebration, Seward NEBRASKAland DAYS, third week, Lincoln Winnebago Indian Powwow, Winnebago, no date set

August4—Centennial Celebration, Old Fort Atkinson, Fort Calhoun 4-6—Centennial Trail Ride, Dodge 5—Centennial Pageant, Beaver City 5-6—Sixth Annual Nebraska Czech Festival, Wilber 5-6—Little Britches Rodeo, Oshkosh 5-6—West Nebraska Threshing Bee, Bridgeport 6—Annual Neihardt Day and "Black Elk Speaks" Pageant, Bancroft 6-13—Parade and Historical Displays, Lawrence 11—Community Picinic, Craig 13—Saddle Club Horse Show, Crete 13—Horse Show, City Park, Cambridge 17—Old Settlers Picnic, North Bend 19—Shrine Football Game, Lincoln 20—Echoes of Oregon Trail Pageant, Fairbury 26—Pioneer Day Centennial Celebration, Inman 27—Country Music Contest, Brownville

September1-7—Nebraska State Fair, Lincoln 2—Centennial Parade, Lincoln 4—Centennial Picnic Celebration, Uehling 18-23—Powwow National Congress of American Indians, Omaha 22-30—Ak-Sar-Ben Championship Rodeo and Livestock Show, Omaha 30—Nebraska University vs. Minnesota, football, Lincoln

October7-8—Midland College, homesoming, Fremont 10—Sioux County Fun Feed, Harrison 13-15—Rod and Custom Car Show, Lincoln 14—Wayne State College, Homecoming, Wayne 20-21—Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation and Ball, Omaha 21—Chadron State College, Homecoming and Band Day, Chadron 28—Hastings College, Homecoming, Hastings 29—Websters County Inter-Faith Religious Music Program, Red Cloud

November4—Nebraska University vs. Iowa State, football, Lincoln 10—Centennial Youth Activities Day, Lincoln 11—Nebraska University vs. Oklahoma State, football, Lincoln 18—Marching Band Festival, Lincoln 23—Closing event of Centennial, Lincoln 25—Nebraska University vs. Oklahoma, football, Lincoln

December1-January 1—Christmas Diorama, Hemingford 8—Great Plains AAU Wrestling Championships, Lincoln 10 and 17—Light of the World Pageant, Minden 25—Christmas

THE END For 35 years... a familiar face around NEBRASLAland We at Weaver's are proud of the fine growth and development that marks our state's 100 years of progress. And we are particularly proud for more than one-third of that time we have been serving Nebraska as a Nebraska owned, Nebraska based company. We join with all Nebraskans in looking back on a past rich with accomplishment, and forward to a future filled with promise. Weaver's potato chips & snack goodies

Would You Believe?

Nebraska is about 430 miles long and 210 miles wide. Total area of the state is 77,250 square miles or about 20 per cent larger than all of the New England states together.

Oil produced in Nebraska totals approximately 19 million barrels per year. Kimball County claims the title of "Oil Capitol of Nebraska", producing 33 per cent of the total.

There are 120 insurance companies which were organized in Nebraska and have their home offices here. Also, there are 695 companies doing business here which have home offices in other states.

In 1872, when John J. Cozad of Ohio traveled through the Platte Valley on the Union Pacific Railroad, he saw on the right-of-way, a sign bearing the words, "100th Meridian". It impressed him as a favorable site for a town so he purchased 6,000 acres of land in the vicinity. By 1876, the town boasted a population of 40 houses and 550 people.

Headquarters for the Strategic Air Command are located at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha. From an underground office beneath the headquarters building, the commander directs SAC aircraft and missiles.

Nebraska has had five capitols—two territorial capitols in Omaha, and three state capitols in Lincoln.

Nebraska has the only one-house legislature in the nation, but other states are eyeing the economy of the Unicameral. In its first year of operation, 1937, the cost was $103,445 compared to the $202,593 cost of the last bicameral session in 1935. The nonpartisan Unicameral began with 43 senators. Now it has 49.

Arbor Day started in Nebraska in the 1870's when J. Sterling Morton started a campaign to plant trees. Nebraska celebrates Arbor Day on April 22nd.

Geologists estimate Nebraska ground water reserves at 547 trillion gallons. If a person perches himself on the Missouri River bridge at Nebraska City, he would have to remain there fore 83 years for that much water to pass under the bridge.

There are nearly 57,000 miles of surfaced roads in Nebraska and more than 5,500 miles of railroad trackage.

Nebraska National Forest, west of Halsey, is the nation's largest man-planted forest. Its 245,409 acres combined with 94,307 acres of trees at Oglala National Grasslands support Nebraska's claim of "Tree Planter's State."

Nebraska holds the title of the "Mixed-bag Hunting Capital of the Nation". Its offering include pheasant, quail, sharptails, prairie, chickens, waterfowl, cottontails, squirrels, varments, mule deer, white-tailed deer, antelope, and wild turkey.

The state has 79 Recreational and Special Use Areas, including four state parks. In addition, there are four State Historical Parks.

A tractor-testing laboratory at the University of Nebraska, started in 1919, is the only one operated in the United States.

Nebraska ranks first in the nation for wild-hay production; third in production of rye and grain sorghum; fourth in corn, winter wheat, and sugar beet production; fifth in alfalfa production. Nebraska's annual farm incomes average more than $12,000 per unit, nearly double the national average.

Nebraska is the only state with all-public power. It has the lowest industrial electric rates between the Mississippi River and the Rocky mountains and the fifth lowest residential rate in the nation.

Nebraska maintains 21 four-year colleges and universities, 5 of which are state-supported, and 6 junior colleges. Both the University of Nebraska and Omaha's Creighton University have professional Colleges of Medicine, Dentistry, and Law.

Lincoln's American Legion Post No. 3 with 6,751 members is the largest in the nation, 232 ahead of the Denver post, its nearest competitor.

THE ENDSCOTTSBLUFF-GERING ...Still making history in western NEBRASKAland

THE FIGHT TO BELONG

by Warren Spencer Growing Nebraska Territory sought to join Union. It took almost 20 years to make itNEBRASKA'S THREE CONSTITUTIONS are locked behind the steel door of a huge vault in the Secretary of State's office in the Capitol, yet they influence thousands of lives each day. They are seldom seen and seldom referred to. Still, they are the keystones of the state.

Behind these yellowing pages is a story of which few people are aware. It is a story of storm and trial, of suffering and of hardship. It is a story of Nebraska.

Though Nebraska became a state on March 1, 1867, the story of her constitution and growth began years earlier. It started with the first trapper who found the land a rich mine of furs and pelts. He came to harvest the fur and remained to make his home.

Later, immigrants poured into the state by the thousands. Many were just passing through, headed for greener pastures elsewhere, but many stayed. So many, in fact, that a territorial government was formed in 1854. Ranchers found the rolling grasslands ideal for their massive herds. Settlers found a new way of life and a chance to grow with the country. And the more who came, the more the question of statehood began to be heard. These people had the land, but they

In 1857, Nebraska Territory covered a lot of West. Present size came with statehood.

1857 MAP, courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society

Whereas the Congress of the United States did by an act approved on the nineteenth day of April, one thousand eight hundred and sixty four, authorize the people of the Territory of Nebraska to form a Constitution and State Government and for the admission of such State into the Union on an equal footing withthe original States, upon certain conditions in said act specified; and whereas said people did adopt a Constitution conforming to the provisions and conditiosn of said act and ask admission into the Union; and whereas the Congress of the United States did, on the eighth and ninth days of February, one thousand eight hundred and sixty seven, in mode prescirbed by the Constitution, pass a further act for the admission of the State of Nebraska into the Union, in which last named act it was provided that it should not take effect except upon the fundamental condition that within the State of Nebraska there should be no denial of the elective franchise or of any other right to any person by reason of race or colore excepting Indians not taxed, and upon the further fundamental condition that the Legislature of said State, by a solemn public act, should declare the assent of said State to the said fundamental condition, and should transmit to the President of the United States anauthenticated copy of said act of the legisllature of said State, upon receipt whereof the President by proclamation should forthwith announce the fact, whereupon said fundamental condition should be held as a part of the— organic law of the State, and thereupon and without any further porceeding on the part of Congress, the admission of said State into the Union should be considered as complete, and whereas within the time prescribed by said act of Congress of the eighth and ninth of February, one thousand eight hundred and sixty seven, the legislature of the State of Nebraska did pass an act ratifying the said Act of Congress of the eighth hundred and sixty seven, and declaring that the aforenamed provisions of the third section of said last named act of Congress should be a part of the organic law of the State of Nebraska; and whereas a duly authenticated copy of said act of the legislature of the State of NEbraska has been received by me:

Now, therefore, I, Andrew Johnson, President of the United States of America, do, in accordance with the provisions of the act of Congress last here in named, declare and proclaim the fact that the fundamental conditions imposed by Congress on the State of Nebraska to entitle that State to admission to the Union have been ratified and accepted, and that the admission of the said State into the Union is now complete.

In testimony whereof, I have hereto set my hand, and have caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of March, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty seven, and of the Indpendence of the United States of America the—Ninety first.

By the President: Andrew Johson William H. Seward Secretary of Statewanted something more; the rights and protection of the Union which was so near and yet so far.

Most of the inhabitants regarded the territorial situation as only temporary and awaited statehood with impatience. Around 1858, the wish which had been simmering fo rso long was brought to light. The Omaha Times noted that the question of statehood should be submitted to a vote of the people. If it came to that there was no question of the outcome with feeling running so high. Both the Republican and Democratic parties, formed some years before in the territory, thought the question over for almost a year and then in 1859, declared they were for statehood. On January 11, 1869, the Territorial Legislature authorized a special election to be held on March 5 to decide on what appeared to be a clear yes or no proposal.

In the meantime, both parties thought more about the proposal and began to hedge. In the election, they mixed up the question with so many regional and local matters that it was impossible to get a clear reading of popular opinion. Included in the election was the nomination of delegates to a constiutional convention. The Republicans elected 40 of the 52 delegates, but because of the confusion the statehood question was vetoed, adn the convention never held.

Then in 1864, the Territorial legislators, Democrat and Republican alike, asked Congress for legislation to claer the way for statehood. On April 19, the

bill was passed and Territorial Governor Saunders scheduled an election of delegates on JUne 6 and a constitutional convention on July 4.

But statehood was still a political football. The Republicans had been most instrumetnal in obtaining legislation as they hoped for party representation west of the Missouri River. Also, they counted Nebraska as a safe entry fo rtheir party. But they were in for trouble from the opposite side of the political fence. Suspecting what was afoot, Territorial Democrats were already planning their evasive strategy.

Those Democrats who had had little to say about the party action before, now found an ideal out. They leaped at the chance to point out that the framing of the constitution and operations of a state government were expensive. In an already indebted territory, the only out would be to raise taxes. This, they assured their opponents, the people would never stand for.

The arguments were sound. Republicans offered statehood to a restless people, and Democrats promised to keep more of their hard-earned money in their pockets. Thus, political pressure began to build on both the convention met in the Territorial Capitol in Omaha and adjourned the same day. No work was done, and the statehood question was again shelved.

It was 1866 when the question came up again. The election campaigns of 1865 made no mention of the issue, but Governor Saunders began to build the case for statehood again in an address to the Eleventh Territorial Congress on January 9. Saunders pointed out that other states, less populated than Nebraska, were already members of the Union. He said that the time was fast approaching when statehood coudl no longer be avoided and urged legislative action.

The legaislature was less than bowled over by the governor's requests and took no action. Saunders and other officials, primarily Republicans, were left to carry the ball.

A secret committee met the same year to draw up a constitution for presentation to the people. Though there is no record of the drafters of this constitution, authorities suggest that they included such dignitaries as Governor Saunders Chief Justice William Pitt Kellogg, Hadley D. Johnson, and O. P. Mason. With their draft finished, the committee turned the constiution over to J. R. Porter, a prominent Democrat favoring statehood, who presented it to the council on February 5, 1866.

The issue immediately became a party matter, and the dominant Republicans railroaded the bill through the legislature faster than the most routine of bills. The same day it was introduced, the bill was placed in committee, and reported back favorably. The council passed it that day with a seven to six vote. On the 9th the bill cleared the house, and Governor Saunders signed it immediately.

Since there were no printed copies for use by the legislators, few of them had any idea what it was about. In the lower hosue it was not even referred to committee. There was a stipulation in it that it could not be amended.

Since the Democrats had raised such a fuss about expense, the constitution provided for the bare minimums. The governor was to receive $1,000 a year; the state auditor, $800; the secretary of state, $600, and the treasurer, $400. Legislative sessions were limited to 40 days, with each legislator to receive $3 a day.

To insure that the constitution reached the people, it carried a stipulation calling for a general vote on June 2, 1866. State officers were also to be elected then. With their backs to the wall, the anti-statehood Democrats hurriedly rallied their forces. They called a convention in Nebraska City for April 19 and nominated J. Sterling Morton for governor—just in case they needed one.

Morton was charged with building the platform for the convention. When the Republicans saw his draft they pracitically laughed him out of the territory. Morton, ready for the rebuke, retorted that the preamble and first resolution were quoted verbatum from Thomas Jefferson's first inaugural address. Perhaps these were not the parts that drew Republican fire. The closing statement quoted Andrew Johnson: "This is and shall be government of white men and for white men." An inflammatory comment even in those days.

With the election drawing near, Morton and his running mates hit the campaign trail. Opposed by David Butler of Pawnee City on the GOP ticket, Morton had his hands full. Where they orator relied on his pomp and ceremony to win votes, Butler was one of the people. His remembered phrase, "I thank God from my heart of hearts..." means little to people now, but back then it got votes.

Even the newspapers noted that Morton outspoke Butler at every turn. The Republican candidate wisely let Morton speak for them both, frequently coming out ahead by doing so. One obviously exaggerated newspaper account states that "It was a bully Democratic speech. Morton only gave 'the lie' direct 19 times, the 'damned lie' 11 times, 'the gol damned lie' twice and wanted to fight once, but was prevented by his friends from getting a well-deserved lashing." Butler managed to stay ahead of the competition.

When June 2 rolled around, there was little anyone could do except wait for the people to make up their minds and count the votes—or not count them. When the smoke cleared, Nebraska had a new constitution by 3,938 votes to 3,838. Butler had defeated Morton 4,093 votes to 3,984. To the Democrats the election was a crushing defeat. To the Republicans it had been in the bad all along.

When the ballots were counted, the Cass County canvassers threw out the Rock Bluffs precinct because of technical irregularities. It seems that come of the people who voted were not residents there, or anywhere else for that matter. Thus, Morton lost 107 votes while Butler was deprived of only 50. In Cass and other counties, soldiers of the First Nebraska Regiment voted here, then returned to their homes in Iowa, Missouri, and other states. Some could not understand why there was any question on their votes. After all, they had never pretended to be citizens here. Canvassers let their votes stand.

The election was a sweep for the Republicans. Of their candidates, all were elected by comfortable majorities except one. One Democrat, William A. Little was elected over his opponent, Oliver P. Mason, supposedly one of the drafters of the constitution. However, before he could take office, Little died. Mason took his place, making the Republican coup complete.

Constitutional proponents sat back to relax, and opponents readied themselves to live with what they could not change. But the battle was only half over.

Next, the new constitution was shipped to Washington for congressional approval. There was one thing wrong with it, however. Within its judicial jargon there was a clause which restricted suffrage to free white men. While the Negro vote was marginal in 1866, there

David Butler rode into office on his reputation of being one of the people. Later they tossed him out

J. Sterling Morton added a bit of dash to campaign. Some said that he wanted to add lumps to opponent

was much sentiment against it, and the framers had included the clause to facilitate acceptance.

In Washington, radical Republicans branded the new constitution a "rebel rag", and many would have nothing to do with it until the clause was removed. Moderates thought it unimportant, noting that 20 states had similar stipulation.

By now, public lands were being chewed up so fast by new settlers that the question of entry into the Union was becoming imperative. Senators began to submit replacement clauses just to get the territory into the Union. But the shenanigans had incurred the wrath of President Johnson, and he was on the verge of vetoing the bill if it did get through Congress.

Finally, Senator Edmunds of Vermont moved to amend the bill to the position that "With fundamental and perpetual condition that...there shall be no abridgement of the original exercise of the elective franchise or of any other right to any person by reason of race or color, excepting Indians not taxed."

So revised, the constitution was returned to Nebraska for ratification. In a full session of the Legislature on February 20, 1867, the body accepted the new condition within two days. On March 1, 1867, President Johnson, still somewhat reluctant, signed the bill and Nebraska became the 27th state in the Union. Nebraska has the distinction of being the only state required to be a free state before admittance.

Though Nebraska was now a bona fide member of the Union, she was far from through with the rigors of constitutional problems. The original document provided for the cheapest known form of government. It limited salaries for governmental officials to such pitiful amounts that it was virtually impossible to attract new and qualified men to office. Also, Governor Butler had become such a menace to the state treasury, lining his pockets and those of picked friends, that he was impeached on June 1, 1871. By now, harried officials realized that it was time to try to rectify their mistakes with a new constitution.

On June 13, 1871, 52 delegates met in the State Capitol in Lincoln to draw up a replacement constitution. For months they haggled, often voting on items only vaguely relevant to the job at hand. Arguments were common occurrences with some bordering on violence. By mid-August, they had reached a decision and prepared the new document for a vote of the people.

Among their suggestions were state control of the railroads and raising the governor's salary to $3,000 per year. They noted that the capitol should remain in Lincoln until 1880, stifling those who wanted it moved because of Butler's graft. Also, they supplied five additions to the new document to be included only if the people wanted them.

The people threw the entire project back in their faces. They wanted no part of it. Once before a slipshod constitution had placed them on the brink of disaster, and they wanted something more concrete this time.

With the rejection of the constitution, Nebraska was in a complete political vacuum. She had no governor and co constitution. William H. James was acting governor, but he was not in control. He dismissed the legislature in 1871, but part of the delegates refused to adjourn. James shut off the coal supply to the chambers, and the majority of the delegates were forced to leave.

He was on a state trip to Washington when the president of the Senate took it upon himself to reconvene the legislature. James hurried back to Lincoln and promptly reversed the (Continued on page 96)

We have made extensive investments in Nebraska because we believe in the future of this great State and because we have found the quality of the people in Nebraska to be outstanding. May I take this opportunity to salute Nebraska on its One Hundredth birthday and pledge the complete cooperation of all our facilities and manpower toward the building of a bigger future in the second one hundred years.

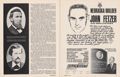

The following facilities are owned by Cornhusker Television Corporation in Nebraska: KOLN-TV/KGIN-TV studios LINCOLN KOLN-TV transmitter BEAVER CROSSING KGIN-TV transmitter HEARTWELL KNU-20/KCU-38 microwave HARVARD KCU-84 microwave DONIPHAN K-70 DP UHF transmitter/translator GOTHENBURG K-70 DK UHF translator/transmitter CAMBRIDGEAN AVID SPORTS FAN, JOHN IS WELL KNOW IN THE BASEBALL WORLD AS THE OWNER OF THE DETROIT TIGERS

EAST SIDE, west side. It made no difference. The dust never settled when "Major Jim" Dahlman was around. Lariats spun and onlookers got "took" with nary a minute's warning. New York City had never seen such hooting and hollering as it did when a Nebraska delegation came to town. They came to hail their fiery orator, William Jennings Bryan, home from an Asian tour. And the short, spunky Omaha mayor, who was in the welcoming group, plucked onlookers off like flies with his trusty lariat. Mayor Jim never let anybody forget that he was from the West.

Yes, things were always astir when that Texan-turned-Nebraskan hit town. But that was his life-- more wild, hair-raising experiences than six men could boast. He left Texas in the 1880's, toting his irons and on the run as a fugitive. His sister's husband was a no good and had deserted her, so justice-loving Jim vowed he would shoot the rat on first sight. After the shootdown, Jim thought he had killed him and took off running.

He changed his name and wandered around in the South for several years trying to avoid the law. Determined to walk a straight and narrow path, 22-year-old Jim set out for Nebraska in hopes of landing a job on the E. S. "Zeke" Newman ranch, being built on the Niobrara River near the present town of Gordon. It was hard to get a job because he was a rough-looking character with only the clothes on his back.

No one realized then that this rough, tough hombre would later become famous as a cowboy, frontier sheriff, confidant of William Jennings Bryan for 40 years, and mayor of Omaha for more than a score of years. For six years, Dahlman rode the range for Newman and throughout the countryside Jim was known as a "good man to tie to". Cowboys like him were invaluable to employers because they would battle to the death with Indian, outlaw, or storm for the cattle that wore their brand. Jim was the man they called on when the time came for the cattle to be rooted out of the Sand Hills during those hard winters. He was the one picked for drives from the Northwest or making Texas Trail treks through Indian territory.

In the winter of 1883, the Pine Ridge Indian Agency needed a bookkeeper and Newman offered his best cowhand, for the big job. It was there that Jim met Harriet Abbott, a Wellesley college student, hired as a governess for the agent's children. The year was gay and fully of socializing, and the dashing and debonair young Texan swept her off her feet. Her teaching career was short-lived as the spare, wiry cowpuncher married her. Undoubtedly, some of her eastern culture influenced the breezy cowboy-politican.

From outlow, county sheriff, to mayor, rugged Nebraska cowboy was wild and woolly as the era in which he livedHome was Valentine, but not for long. The young couple soon moved to Chadron, where Jim established a small ranch and meat market. After the move to Chadron, Jim's life as a real Nebraskan began. During the next 11 years, he served as sheriff of Dawes County and major of Chadron. Being sheriff on the northwestern Nebraska border was no easy task as cattle and horse thieves were numerous and bandits ran wild. It was good old horse sense and strategy with his law enforcing that kept Jim from joining the men who sleep their last snooze under the frontier sod.

At that time, sheriffs of several Wyoming, Nebraska, and South Dakota counties were on the watch for a "plain bad" outlaw. Tall and powerful, quick on the trigger, he had boasted he would never be taken alive. Sheriff Dahlman was informed that the ornery guy was in the post office. Jim, less than half his quarry's size, crept across the floor, and grabbed the outlaw's gun without a warning. "Put 'em up!" The bandit's hands flew ceilingward. When he found out he had been nabbed by a gunless man, the bandit vented his disgust and rage in a torrent of foul language.

Dahlman was sheriff of Dawes County for nearly two years when an event took place which changed the whole course of his career. At least it launched him on his state-wide political and civic activities and brought him a lifelong friendship. In 1888, Jim met William Jennings Bryan, (Continued on page 90)

PLAIN JIM

Photographs, courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society

JANUARY, 1967 21

BATTLE CRY OF THE PLAINS

Red Men arose in avenging fury when Harney kindled fire at Ash Hollow, engulfing the prairie for 36 years by J. Greg SmithTHE VALLEY looks peaceful enough. A good place for picnicking. Or exploring. Or just plain relaxing. Or climbing the sandstone bluffs that crop out along the canyon walls. But no place for dying.

They call the creek, the Blue Water, a busy little stream that hurries along to its rendezvous with the Platte River, some six miles from historic Ash Hollow. Drive 28 miles northwest of Ogallala on U.S. Highway 26, and you'll find it; looking much the same as it did on that fateful day, so long ago, when it ran crimson with the blood of Indians butchered by saber and cannon.

It was raining that bleak September day in 1855. The tiny rivulets of water rushing down the canyon walls met and intermingled with pools of red. Each pool had its own source--a warrior

hacked down here, a young boy shot clean through over there, and up there, the scattered remains of an old woman caught in the shell fire.

Mixed in with both blood and water were the tears of those who had escaped this senseless slaughter. But the keening cry of Little Thunder's Brule Siouz would soon become the battle cry of all Plains Indians and the terrible revenging would go on until no more tears could be shed. For 36 years the battles would rage before the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe would give up the land called Nebraska to the white man.

If the massacre of the Brule at the Blue Water was senseless, the reason behind the act was even less so. A Mormon cow, a straggling bag of bones too long on the trail, had kicked the spark that set the prairie aflame with the cry of war.

The incident had occurred the year before east of Fort Laramie. Most of the Sioux were encamped along the North Platte River waiting their issuance of goods under the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851. They, along with the other Plains tribes, had agreed to let the long strings of white-topped wagons go through unharmed. Although game was becoming scarce along the trail and the white man's diseases were taking their toll, the Indians had caused little trouble.

Nor were they causing trouble when the Mormons passed their camp. When the cow strayed into their tepees, they considered her as their own and soon had her butchered and eaten. The enraged emigrant reported his loss to a hot-headed West Point lieutenant named Grattan who immediately ordered out 30 men and 2 cannons.

Storming into the Sioux Village, he demanded that the Brules give up the brave who had killed the critter. Conquering Bear refused and Grattan gave the order to fire. The chief went down with the first blasts, mortally wounded. The enraged Indians charged over the cannon crews, and moments later Grattan and his men lay stripped and mutilated.

All the pent-up frustration of the Sioux was taken out on the corpses. And when they tired of this, they struck out at hapless whites along the trail. They stalked the emigrant road, avenging the death of Conquering Bear and the others who fell before Grattan's cannons.

But at the Blue Water, it was the white man's turn for avenging. The troops under General William Harney were determined to get Grattan's killers.

While Harney parleyed with the Sioux chief under a flag of truce, his men moved into position. The infantry and artillery were on one side of the canyon, the cavalry was on the other. When Harney gave the signal, they crashed down on the unsuspecting Brules.

The troopersr didn't much care who got in front of their sights. "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," be they man, woman, or child. Those that escaped the first thundering blast worked their way up the canyon, hiding in the cave-like outcroppings at the top of the slopes. Artillerymen zeroed in on the helpless clusters, taking a heavy toll. Others fled ahead of the charge, their bodies strung out five miles up the ravine.

Harney finally tired of the chase and ordered his men to round up the survivors. He chained the savages together and headed for Fort Laramie. But there were those who were beginning to wonder who was the most savage.

There were a few who were repelled by Harney's actions. But very few. Most shared the opinion that the only good Indian was a dead Indian.

The Indians were held in disdain by most Americans; uneducated heathens to be conquered and pushed 24 NEBRASKAland aside. It had been so since Colonial times; the various tribes forced west ahead of civilization. At one time the land beyond the Missouri River called Nebraska was considered a dumping ground for the displaced red man. But as settlement pushed ever nearer, he had to be moved again.

Nebraska's eastern tribes had been exposed to the white man since the first fur traders came up the river. When civilization pushed across the Missouri, they offered no resistance to its coming. Plied with trinkets and liquor and weakened by the whit eman's diseases, they were willing to accept any offer for their lands.

The Otos, Iowas, and Missourias, small, semi-sedentary tribes living near the mouth of the Platte, were uprooted and moved south. The Omahas and Poncas, under constant attack from the Sioux in northeastern Nebraska, finally gave in to civilization's pressures. The Omahas ceded all but 300,000 acres in 1854; the Poncas gave up everything in 1877 and were sent to Indian Territory.

Though defeated in body, the Poncas won one great victory for all Indians. Their battle was not fought on the plains, but in a federal court in Omaha. There, Chief Standing Bear proved to all men that "An Indian was a person within the meaning of the law". The Bear and about 200 Poncas were allowed to return to the Niobrara to live on lands ceded them in severalty.

One of the uprooted woodlands tribes, the Winnebagos, managed to stick it out in Nebraska. Following the Sioux uprising in Minnesota, they were hustled west to a reservation in South Dakota. With the people starving, the chiefs sent scouts out to find a mroe productive land. Through the encouragement of their agent, Robert W. Furnas, the Omahas let them stay at their small reservation, finally ceding a part of their lands to the Winnebagos. The arrangement continues today.

For a time, it seemed that the Pawnee would ever remain in their beloved Nebraska. Their ancestors had lived along the Loups and Platte rivers for as long as anyone could remember. These were an advanced people, sharing their time between raising corn and hunting buffalo. Early missionaries estimated the population at above 10,000 in 1833. But by the 1860's, disease and their hated enemy, the Sioux, had reduced their number to less than 4,000.

Though the Pawnee had sniped away at emigrant trains on occasion and stole horses whenever they got the chance, they soon became the willing ally of the cuited the best of their warriors to serve on several major expeditions. They also played a key role in protecting workmen pushing the Union Pacific's end-o-track deeper into the wilderness.

Any appreciation by the whites for such support was short-lived. The Pawnee ceded all of their lands south of the Platte in 1833. Fifteen years later they sold an 80-mile strip along the Platte including Grand Island. And in 1857 they gave up all, except a 15 by 30-mile strip along the Loup. Agreement to this last treaty at Table Rock assured them of protection from the Sioux.

But it was protection that was never forthcoming. On a hunt along the Republican in 1873, the Pawnee were ambushed by the Brule and Oglala Sioux. The Dakotas finally had their chance for revenge, slaughtering over 170 men, women, and children in what is known today as Massacre Canyon.

This was the crushing blow that sent the Pawnee to Indian Territory. Most of the tribe headed there in 1875. The next year their land was exchanged for lands in what is present-day Oklahoma.

It could be said that the tribes along the Missouri River and even the Pawnee were a pushover to the white man's whims. Not so with the Sioux and Cheyenne. These were peoples steeped in the traditions of fighting for what was their own. They were warrior tribes, each man measured by his bravery in battle. They had long memories and a burning desire to square old scores.

None could forget the senseless acts of Grattan or Harney. Nor the treaties made and broken. The Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapahoe and other western tribes had met at Fort Laramie in 1851. There they agreed to keep the peace, allow emigrants to go through, and remain within certain tribal boundaries. For this they were guaranteed annuities for the next 50 years.

But even before the ink was dry, the treaty was broken. The Senate reduced the number of years annuities would be made from 50 to 10. Then they ratified the treaty without resubmitting it to the Indians. The western tribes stuck to the terms of the treaty, however, until Grattan charged into Conquering Bear's Brule village. The Sioux seemed cowed by Harney's actions, but they were only waiting for a chance to get their revenge. That came when the Civil War stripped the frontier of its soldiers.

The first harbinger of what was to come came at the uprising of the Minnesota Sioux in 1862. Travel along the trail was becoming increasingly difficult. Then in 1864 the western tribes struck with a vengeance.

Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and Sioux launched an attack all along the Platte Valley. Stage stations were burned to the ground. Emigrant trains were waylaid. Homesteads as far east as the Blue River were plundered. Settlers had no warning of the Indians' coming, and the toll was heavy throughout southeast Nebraska!

In desperation, the army fired the prairie from Fort Kearny to Julesburg. But even this could not stop the hostiles. By the end of the Civil War the situation had reached the critical stage, with the white man barely holding on in Nebraska's western plains.

More fuel was added to the fire when Black Kettle's southern Cheyennes were slaughtered by Colonel J. M. Chivington's Third Colorado Cavalry. The Cheyennes had voluntarily surrendered and were awaiting peace negotiations when Chivington struck. Again, men, women, and children were killed, a repeat performance of the Battle of the Blue Water.

"Kill all. Scalp all," the troopers shouted, "Nits make lice!"

A deadly pattern of avenging and revenging was evolving, with neither side willing to give quarter. After investigating the massacre at Sand Creek, Congress created a Peace Commission in 1866. Its purpose was to remove, if possible, the purposes of the Indian wars. But to do that would require the whites to adhere to stipulations of the Fort Laramie treaty. This, they were unwilling to do.

Gold had been discovered in Montana, and the government pushed for a road through the heart of Sioux country. The whites had broken the treaty by being in Montana. The road would be only a further violation. Spurred on by the Cheyenne, who had escaped the Sand Creek Massacre, the Plains Indians were determined to stem the tide of white men flooding over their lands.

Troops moved up the Bozeman Trail, establishing

Forts Phil Kearny, Reno, and C. F. Smith. No sooner

JANUARY, 1967

25

were they built than the Indians struck with fury.

Red Cloud's Oglalas ambushed Colonel W. J. Fetterman's

command, killing all 81 men. The road and the

forts were under constant harassment, and little

traffic moved up the trail.

were they built than the Indians struck with fury.

Red Cloud's Oglalas ambushed Colonel W. J. Fetterman's

command, killing all 81 men. The road and the

forts were under constant harassment, and little

traffic moved up the trail.

The Peace Commission sent runners out to the tribes in 1867, inviting the Sioux to come to Fort Laramie for another parley. Red Cloud refused, saying that there would be no peace talks while the Bozeman Road and its forts were open. In desperation, troops were withdrawn from Kearny and C. F. Smith and the road finally closed.

From all appearances, the Sioux had won the day. But it was a sorry victory. Red Cloud and his chiefs met with the commission, agreeing that they would stay west of the Missouri and north of Nebraska. They also agreed to let roads and railroads go through their land. In short, they agreed to reservation status. But "they" didn't represent all of the Sioux.

Crazy Horse and many other Oglala and Brule warriors wanted no part of such a sellout. They stayed away from the reservations that were finally established near present-day Crawford and Chdaron, Nebraska. These non-treaty Sioux joined Cheyennes and Arapahoes in striking terror across the Plains. Secretly, even they knew that theirs was a losing battle.

Bony longhords were moving in to take the place of the fast-disappearing buffalo. The railroad had sliced their land in two. And the talking wire of the telegraph reported their every move. Squatters cabins were springing up everywhere and only in the north country were the Indians able to move with any of the old freedom. Then even this land was threatened.

Custer led his "scientific" expedition out of the Black Hills, reporting to the world that there was gold at the grass roots. Neither treaty nor army could hold the prospectors back. Again, the reservation Sioux were called to the treaty table, this time to sell the Black Hills to the white man. When they refused, the government served notice for all Sioux to come into the reservations. If they did not comply, they would be treated as hostiles and forced in by the army.

This final showdown was inevitable. Civilization was crushing in on the Indians from every side. To try to stem the tide, the non-treaty Oglala, Brule, Hunkpapa, Minneconjou, and all the lesser tribes of the Sioux joined the northern and southern Cheyennes and the Arapahoe.

There had nevery been such a gathering. Nor would their ever be again. The army moved out to attak them in a massive three-pronged offensive. Crook with 800 men headed north from Fort Fetterman. Gibbon with 500 men moved down from Montana. Terry with 900 men pushed west from Fort Abraham Lincoln. With him rode Custer.

The flamboyant general was not the first to feel the sting of the Indian's wrath. That honor was held for Crook. His troops were sent reeling at the Battle of the Rosebud, June 17. Then it was Custer's turn. June 25, 1876 will ever be remembered as the Indians' greatest hour, the day they massacred the Seventh.

For two months, the hostiles eluded Crook and Terry. Finally, one by one, the various bands started coming in. Crazy Horse held out until the next spring before finally coming to Fort Robinson. On September 7, 1877 the great chief lay dead, the victim of intertribal intrigue.

For all practical purposes, Crazy Horse's death marked the end of the Indian wars. He had seen Conquering Bear go down under Grattan's cannons. He had been at the Blue Water. And from that moment 26 NEBRASKAland on he was pledged to fight a never-ending battle against the white man.

But the battle was finally over, with no more avengings to be done. Only a few sporadic outbreaks would mar the peace that had come to the Nebraska scene. Dull Knife's northern Cheyennes made a desperate bid to return to their homelands in Montana from Indian Territory, but were captured and detained at Fort Robinson.

One more time the Indians would try to return to the old days and the old ways. They put on "bullet-proof" shirts and danced the Ghost Dance, calling to the Great Spirit to restore the game and drive out the white man. But the shirts were not bullet proof and still more Sioux were slaughtered on a cold December day in 1890 at Wounded Knee, just north of the Nebraska-South Dakota border.

The story of the Indian in Nebraska is not a pleasant one. It is a tale of treaties made and treaties broken, promises made and promises broken. Of rot-gut whiskey that would break the pride of even the strongest man.

Now, 100 years later, it is easy to point the finger of blame. But as Nebraska observes its Centennial, one must ask, "Who are we to judge?"

Two distinct cultures were thrown against each other. The Indians believed that only the Great Spirit could own the land. It was not theirs to sell or barter. And to be a man, a warrior could not be a tiller of the land. But the white man said that to own the land was to own everything. And to make that land produce was a man's destiny, if not his obligation.

The land has produced for both white man and Indian. Both will agree that it is a good land, its soil made richer by blood spilled on a long-ago days when Nebraska was but a prairie to roam.

THE END JANUARY, 1967 27

THE BIG MEDICINE TRAIL

Triumph and tragedy stalk an age-old pathway as young America roars West by Bess Eileen DayMANY BIZARRE cargoes jolted along the old trails that wound across what is now Nebraska. Cargoes that rode the big freighter wagons, bulged the saddlebags of horsemen, or chafed the shoulders of those who carried their world on their backs.

Among the more whimsical loads toted on the Oregon Trail was Mollie Dorsey Sanford's coop of chickens. A bride of three months, Mollie at Nebraska City heard that chickens were worth $5 each at Denver. So when the Sanford-Clark party started for the Colorado gold fields in 1860, she fastened a coop with a half-dozen hens and a rooster behind her wagon.

On crossing their first stream, the rooster was drowned. Mollie wrote in her diary: "The poor rooster will not herald the coming dawn for us again. This is our first disaster." Luckily, the hens survived to produce eggs at $2 a dozen at Denver and to provide Mollie with her own little gold mine.

Fortunately, all of Mollie's disasters were light,

but thousands of other travelers on the early trails

were not so fortunate. Some were killed and scalped

by the Indians. Others survived the journey across

Nebraska only to die of thirst or starvation on the

western desert or freeze to death in the northern passes.

by the Indians. Others survived the journey across

Nebraska only to die of thirst or starvation on the

western desert or freeze to death in the northern passes.

In the vast Nebraska Territory that once comprised all or part of six present states, that great father of all trails west was the Big Medicine Trail of the Indians. First followed by the elk, deer, wild horse, and buffalo, and later by the Indians, the Big Medicine Trail was really a network of paths crisscrossing the prairie country. Numerous feeder trails led into it from various areas, but like a modern highway, it had its major traffic patterns. The first trail of this network to gain more than local identification was the famed Louis and Clark Trail of 1803-07.

In Nebraska proper, the Big Medicine mostly followed the south side of the Platte River and was the ancestor of the Oregon Trail which was first used by early trappers and traders en route to the mountains.

Second cousin to the Oregon was the Mormon Trail. It clung to the north because religious differences and belief in multiple-marriage had brought persecution to the Mormons in the East and they sought escape from the main stream of emigration.

In 1846, on the march toward their Zion at Salt Lake, the Mormons crossed the Missouri River near Florence, Nebraska adn built their "Winter Quarters", housing a population of 3,500. Disease, privation, and winter decimated their numbers and 600 of the faithful are buried there.

After a year of farming and harvesting the main caravan moved on in 1848, taking with them 560 wagons. About 10 years later, a new group of Mormon converts from the British Isles and Europe came to America and headed west. Lacking wagons, they were advised to use handcarts. About 3,000 carts were pulled over the long, long trail from their staging area in Iowa City to Salt Lake City. Usually the men pulled with the women and children pushing, The handcarters with their 500-pound loads could make 30 miles a day, double the average distance made by a wagon train.

As late as 1857, Mormons were still going through by handcart. A splinter group came through Fort Kearny late that year and the fort commandant held them up and put them to work getting in hay and cord wood, because it was too dangerous for them to travel with winter close upon them. They worked that winter and were paid wages. In the spring they went on.

As tales of tragedy came from the Mormon Trail, so later stories of notorious characters and crimes filtered out of the Sidney-Black Hills Trail area. It 30 NEBRASKAland became the hide-out of numerous desperadoes, killers, stage, and bank robbers.

Starting due north of Sidney, this trail crossed the Oregon Trail, and passed through Cheyenne, Morrill, Box Butte, and Dawes counties. A great freighting road, it hauled supplies from the railroad at Sidney to the mining camps. Gold from the Black Hills was the lure that drew the owlhoots.

The Niobrara Trail was a natural trail that followed Nebraska's Niobrara River. Later, it was joined by a trail coming up the Elkhorn Valley, to form another route to the Black Hills.

Signs on the trails did not originate with the white men. Long before their coming, the Indians constructed their weird and mysterious Medicine Circles of buffalo skulls. Early travelers in Nebraska found these skull circles not far from the Big Medicine Trail along the Platte. They were set in the ground in huge rings, and according to the Indians, had a magic power to draw in the buffalo herds.

Fantastic and fascinating as were the Medicine Rings, some of the travelers and their doings along the Oregon Trail were even wilder. The lure of the wilderness, the lust for gold, the urge to travel, to seek adventure, and the promise of a hunter's paradise drew explorers, gamblers, scouts, soldiers, fur traders, artists, writers, and even foreign royalty.

European nobles who rode the trail included Prince Paul of Wurttemburg, Prince Maximilian of Prussia, and Captain William Drummond Stewart, a British baronet.

Stewart, Maximilian, Washington Irving, and Charles Augustus Murray were a few of the early writers who came to the Platte Valley for material. George Catlin, John James Audubon, Karl Bodmer, and Alfred Jacob Miller were among the artists who left pictorial records of the Plains Indians and Nebraska landmarks.

Miller in his water-color studies did as thorough a documentary on Indian life as a modern photographer. He was the first notable artist to travel extensively in the West and painted Indians peaceful in their lodges, on the hunt, on the trail, and on the war-path. He painted Chimney Rock, Courthouse and Jail Rocks, Ship Rock, and Scott's Bluff, all landmarks along the Oregon Trail.

A different breed of men from the artists and adventurers

were the leaders of the pack trains for the

fur companies. In April 1832, William Sublette started

off with a hundred-horse caravan from St. Louis with

JANUARY, 1967

supplies for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company on the

Green River in the present state of Wyoming. In May,

he was joined by Oregon-bound Nat Wyeth and his

company of 50 from Boston. Together they pioneered

the route which became the main line of the Oregon

Trail between Independence, Missouri and the Platte

River. Crossing the Missouri River in Kansas, they

turned northward along the Big Blue for 40 miles, and

then followed the Little Blue River to what is now

Hastings, Nebraska, and on down the wide valley of

the Platte. Ralph Moody, writing of this expedition,

describes an incident of the trip.

supplies for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company on the

Green River in the present state of Wyoming. In May,

he was joined by Oregon-bound Nat Wyeth and his

company of 50 from Boston. Together they pioneered

the route which became the main line of the Oregon

Trail between Independence, Missouri and the Platte

River. Crossing the Missouri River in Kansas, they

turned northward along the Big Blue for 40 miles, and

then followed the Little Blue River to what is now

Hastings, Nebraska, and on down the wide valley of

the Platte. Ralph Moody, writing of this expedition,

describes an incident of the trip.

"There a war party of Pawnee overtook and passed the caravan, proudly waving a few bloody scalps just lifted from their enemies, the Kansas Indians."

The combined caravans of Sublette and Wyeth plodded westward along the south bank of the Platte. To avoid quicksan, Sublette followed the river beyond the South Platte to the present borders of Colorado, then along Lodgepole Creek for 30 miles, then north across a high divide, known as the Thirty-Mile Ridge, and on to the North Platte River below Courthouse Rock. Robert Stuart had come east from Oregon along this route in 1811, but his report was virtually erased by the War of 1812. So, Wyeth's party receives credit for being the first to reach Oregon by following this trail.

Three years later, in 1836, at Bellevue, Nebraska, the Tom Fitzpatrick pack train assembled and it was, according to Moody, the strangest that ever set off for the Rockies.

"The main body was made up of 400 pack animals and 70 frontiersmen, rough, tough American mountain men, French-Canadian trappers, and Indian half-breeds. In ludicrous contrast was Sir William Drummound Stewart and his party of British sportsmen, bound for a 'rousing buffalo hunt' on the prairies. The sportsmen were accompanied by an array of men servants, gunbearers, and dogs, and traveled in several ornate wagons, each drawn by six mules in glittering harnesses. To complete the assemblage the missionaries trailed along behind."

The missionaries, the Whitmans and Spaldins, were loaded with furniture, clothing, boxes of religious books, and provisions for months. They brought 2 wagons, 14 horses, 6 mules, and 17 cattle, mostly milk cows. Much of what they brought they had to leave along the way, and reached Oregon with only half a wagon box on one axle.

Among the first white women to travel on the Oregon Trail were the wives of these missionaries. Narcissa Whitman was a beautiful blonde and excited much attention.

"Women," Moody says, "were not only a curiosity to Fitzpatrick's rough crew but the object of more than a little rough banter. Sister Spalding was shocked and appalled, but Narcissa Whitman glowed with exhilaration at the exciting adventure before her. After a few 32 NEBRASKAland days she won the admiration of the entire crew, and they watched their language in her presence. Whenever game was killed, the choicest cuts were brought to her tent. In return, the bearer's canteen was always filled with fresh milk."

Later, when the missionaries attended a fur-trading rendezvous the women were again the center of attention. Many of the mountain men had not seen a white woman in years and they were fascinated by Narcissa's beauty.

Moody wrote: "The Indians almost worshipped her. The squaws gathered in a throng, to touch their fingers to her white skin, marvel at her blue eyes, and admire her clothing."

Although Whitman had a tough time with his wagons he was not the first to take wheeled vehicles over the trail.

Tom Fitzpatrick and Robert Stuart were among the first to believe the entire route of the Oregon Trail could be traveled by wheeled vehicles. In November of 1824, Fitzpatrick urged General William H. Ashley to use a wagon train to transport supplies to the rich fur country beyond the Continental Divide. The general risked one wagon and made it.

When Captain Benjamin Bonneville took a full wagon train through in the late 1830's, the way west began to broaden. In 20 wagons, Bonneville was able to transport twice the stock carried by Sublette in 1832. By the time he reached Laramie Fork, however, he experienced the "cussedness that tried the souls of emigrants" in the shrinking of wood in hubs, spokes, and felloes so tires fell off, and wagon boxes came apart.

Gullies, canyons, hillsides, and cliffs slowed him up. He had to stop to corduroy soft spots with logs and brush, build half roadxs called dugouts, and let wagons down slopes by windlasses. When he came to unfordable rivers, he had to take the wheels off and make wagons into real prairie schooners by sheating them in hides so they could be ferried across.

Some 20 years after Bonneville, came the movie-sized trains of a hundred or more wagons. They did not always circle at night or form a horseshoe barricade into which to drive the livestock in case of an Indian attack. Instead, the wagon master made the decision about the train's night formation, using his knowledge of the terrain, the length of the stop, and the eminence of danger. Once the wagons were drawn up though into an over-lapping barricade, they did provide a powerful bulwark against attack.

Wave after wave of emigration hit the trails West. In the 1830's, the backwash of European unrest and economic upheaval sent a flood of immigrants to American shores. The potato famine in ireland also contributed to the traffic. The cities on the coast absorbed some, but many took to the wilderness on a wave of discovery. In the 1840's and early 1850's, a tidal wave of gold seekers bound for California came through, and in 1854, when the (Continued on page 98)

Photographs, courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society

MANY FACES OF MARKET HUNTING

CALL IT AN eulogy to market hunting or a sudden awakening of the public to the rapid decline of wildlife; this 1877 letter, written by S.Now, 100 years later, it is easy to point the finger of blame. But as Nebraska observes its Centennial, one must ask, "Who are we to judge?" Two distinct cultures were thrown against each other. The Indians believed that only the Great Spirit could own the land. It was not theirs to sell or barter. And to be a man, a warrior could not be a tiller of the land. But the white man said that to own the land was to own everything. And to make that land produce was a man's destiny, if not his obligation. The land has produced for both white man and Indian. Both will agree that it is a good land, its soil made richer by blood spilled on a long-ago days when Nebraska was but a prairie to roam.P. Benadom of Lincoln, Nebraska, can be both.

"During the winter of 1875, I was engaged in shipping prairie chicken, quail, and other game to eastern cities, principally Boston and New York. I was only shipping about six weeks and during that time I sent off 19,000 prairie chickens and 18,700 quail. About half of these were caught in Lancaster County. I cannot tell how many other parties who were in the same business shipped, but I am satisfied that the destruction of these birds should be stopped."

Between these lines is a fantastic story of abundant wildlife, pioneer hardships, and the building of our modern civilization.

Though many yarns have been written about market hunting, few have mentioned the key part it played in the settling of Nebraska. What would have happened if the unbelievable herds of buffalo had not blackened the Plains? Would the wagon trains have been able to course through the Platte Valley? Would the railroads have been built? Could the homesteader have survived without living off the wildlife? Perhaps all these things would have been accomplished, but the settlement of the West would have taken much longer than it did without the presence of abundant wildlife.

The story of wildlife and its influences on the settlement of the West begins back when Nebraska was Indian territory, encompassing what is now Nebraska, the Dakotas, parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and Montana. Market hunting began in the 1820's with the establishment of Fort Atkinson on the Missouri River, near the present city of Omaha. It is documented that the Omaha Indians voiced their complaints against the military for the decimation of wildlife in the area. Following the fort, came the Mormons in the 1840's, and their camps along the Missouri took a further toll of wildlife. There was no distinction of species, if an animal or bird could be eaten it was killed.

This early hunting contained all the basics of market hunting in that the hunter supplied game to the early settlers and travelers in trade for both money and supplies.

During the mid-1840's, the wagons in ever-increasing numbers, began to roll across the Platte Valley and over the Oregon Trail. Along with the traffic on this famous road to the West came the Mormons, struggling over the trail that now bears their name. All of these people depended upon game to some extent for food and it is no wonder that with the passage of approximately two million people over a relatively short space of time, wildlife numbers began to decline. The early immigrants had little if any way to keep meat fresh, so it was a matter of killing for the next meal.

Wildlife is vaguely described in diaries of the travelers on the trails. The buffalo takes precedent because of the magnitude of the great herds. "A sea of beasts," writes one, "a herd covering an area 10 miles square"..."at least two million animals"... "travel was held up four hours as the herd passed in endless procession." So goes the story of the great herds as the white men first viewed them.

The importance of wildlife to the Indian was first reflected at Fort Atkinson, but by the mid-century the red man could see the effects of the white man's invasion and his guns. The tribesmen became concerned and if any one thing triggered the Indian wars, it was the rape of the wildlife resources on which the Indian lived.

After 1854, settlers began staking claims throughout

the territory. Their arrival was followed by the

building of the railroad. These two events marked the

JANUARY, 1967

35

beginning of the end for the extensive herds of game

in the state.

beginning of the end for the extensive herds of game

in the state.

The variety of game in Nebraska at the time is well documented and the lists include elk, deer, antelope, turkey, buffalo, quail, prairie chicken, and sharp-tailed grouse in addition to mountain lions, bighorn sheep, coyotes, wolves, and bear. Waterfowl and shore-birds were abundant. The trappers worked the beaver first and then turned to muskrat, bobcat, coyote, and wolves. As the railroad began its race across the state, the need for buffalo meat to feed the construction crews brought in hunters to meet the demand. Buffalo Bill Cody was undoubtedly the most famous of the buffalo hunters, but whether or not he was the most successful is debatable.