NEBRASKAland

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS NEBRASKAland OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland November 1966 50 cents Taming the snake Perilous float on a beautiful river Black Bass at Red Willow HER NAME IS BARBARA She finds close-to-home hunting bonanza The Setting Sun ... Western skies captured in glorious array

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome.—Editor.

STOVE AND SNAKES- We were much interested in the article, "Cody's Contentment" in the July issue of NEBRASKAland. We had just recently taken some relatives to this interesting place. One thing that interests us especially is the old stove in the kitchen. This stove belonged to our aunt, Mrs. Sam J. Ostergard who now lives in Arnold. Many delicious meals were cooked on this stove through the years. She is very proud that the stove now stands in the kitchen at Scouts Rest.

"Recently my daughter-in-law and granddaughter found an albino rattlesnake on their place. It is too bad that they didn't capture him alive as it was numb in the early morning cold and could have been put into some container, but one's first thought on seeing a rattlesnake is to kill him so he will no longer be a menace.

"The snake was a very light creamy white, completely devoid of markings. He was not very long, but a bit thicker than some of that size. He carried six rattles. He had the colorless eyes, which one would expect in an albino.

"Just about a quarter of a mile from their place is an old prairie dog town where many rattlesnakes spend the winter, and we thought the snake might have come from there. We have had many experiences with rattlesnakes through the years, some pretty scary, but this was the most unusual."-Mrs. Harry Ostergard, Gothenburg.

HORSE FAN —"I am presently enjoying my second year of Outdoor NEBRASKAland. Your rodeo roping pictures are excellent. They are especially good at showing the quality of the horses. I read your article on the Columbus, Nebraska thoroughbred stable. Last August, I visited the stables. I am looking forward to more of these good articles."-LeRoy Shafer, Birmingham, Alabama.

DEER SANDWICH-"I was born near Miller, Nebraska, on October 2, 1889 on a pioneer tree-claim homestead. I left the farm in 1913, and the state in 1920. I have been back only a few times since. I had not heard of Outdoor NEBRASKAland until just recently when I called on a friend who came from Merna, Nebraska. She loaned me some copies, and I have had great enjoyment reading them. My son is very interested in wildlife here in Arizona, and I will share my magazines with him.

"I also recently received a NEBRASKAland calendar from a person I knew as a neighbor in 1911-1913. He is now a resident of Washington. He tells me that Nebraska again has much wildlife and is a great state for hunters with bow, gun, and camera.

"I remember as a boy hearing about a wild deer that somehow got down in Buffalo County in our section north of Miller. The whole male population gathered up the muzzle-loading shotguns, what rifles they had, some revolvers, I suppose, and the rest took pitchforks. They chased that poor deer all over the place until they killed him. About all each got was enough venison for a good sandwich."-Ray N. McLamm, Tucson, Arizona.

OVEN-FRIED-"Enclosed please find two pictures I took to show the ladies how I like to 'oven fry' fish.

'This method is not new, but so many times we cook, flour, season, and slap

"Dissolve salt in combined milk and water: dip fish, then roll in corn flakes. Bake in shallow pan that has been greased. Check from time to time, though it usually takes 15 minutes. Makes six servings. Serve with tartar sauce or lemon wedges." —Mrs. Ilene Duemey, Lincoln.

OLD DAYS - "I read with a great deal of interest The Return of Standing Bear' by Warren Spencer in the March NEBRASKAland.

"I am the granddaughter of a Nebraska pioneer who homesteaded in Pierce County in 1869.

"My father, who was 14 years old when he came to Nebraska, told me so many stories of those days and about the Indians.

"This story about the Poncas my father told me, and many more. The Poncas were a very friendly tribe, and at different times during the year came to the North Fork, which runs through our place. They would come with their Indian ponies, poles tied to the sides, and camp here to hunt and fish.

"A bend in the river just northwest of our home was a favorite spot. They would visit my family, who then lived in a log cabin.

"My cousin was born here in 1870, and the Indians had never seen a white baby, so they always stopped to look. They would come to the log cabin and peek through the window, never coming to the door.

"By the way, I have these windows in a family museum we have. Children who visit our museum are always so thrilled when I tell them, 'You are looking through windows the Indians looked through.'

'The Poncas came to bid my family good-bye when the government was taking them to Oklahoma. My father said they cried so bitterly. He said he never saw anything sadder than the sight of an Indian crying, and my family cried with them out of pity, for they felt very kind toward the Indians.

"When they came back, more than half had died in Oklahoma. They came to see my family and hugged them for joy.

The trail they traveled was past our home. It was also the first road the pioneers traveled.

"My grandparents and parents have passed on, and my husband and I are now living on the 83-year-old family home. My family has been here continually since 1869. They lived in the log cabin until 1883.

"I thought this might interest you, since it is part of Nebraska history. Few old-timers are left to tell the story."- Mrs. E. W. Hansen, Pierce.

RODEO BUFF —"I have enjoyed your recent coverage on various rodeo events,

such as in the June issue, and your story

on the rodeo clown in the July issue. I

am a rodeo enthusiast, as are the majority of people in this part of Nebraska.

It is pleasing to note that you take the

time and space to give the rodeo sport a

spotlight, inasmuch as it seems to be

very much neglected throughout the

nation.

very much neglected throughout the

nation.

"I am enclosing an article from the Rodeo Sports News, the rodeo cowboy's newspaper, which also mentions the nice coverage you have done.

"Because the rodeo sport is part of Nebraska's heritage, it is wonderful that such a fine magazine will stand behind it so well. I know I speak for many others who also enjoyed the articles very much." —Yvonne Hanson, Gordon.

BALD EAGLES-"I was thrilled to read about the Bald Eagles of Jeffrey Reservoir in the March issue. I think that Mr. Hornbeck should be congratulated on the beautiful pictures that he obtained for this story.

"I live at Jeffrey Lake and am one of the operators who work in the Jeffrey Hydro Plant.

"From our control room window we could see those very same eagles as they dove down from their perches to seize passing fish.

"If the readers of NEBRASKAland could have seen the conditions that Mr. Hornbeck worked under, they would appreciate this article to the utmost. There were many mornings when he sat and waited in his blind when the temperatures would have made a sled dog howl in protest." —Dale L. Craig, Brady.

FISHING GIMMICKS-"The account of sauger fishing was real good. Gosh, it makes me want to take off for Gavins Point Dam with pole and line. The way the story is written is as refreshing as an ice cold bottle of soda on a hot day.

"I was especially interested in the part about houseboats. I am nuts about these boats for they provide the fisherman with some of the comforts of home. In fact, my last one was equipped with rod and reel holders on its deck, and small bells tied to each pole which jumped with joy when a fish was hooked.

"To provide my hooks with fish, I filled several 55-gallon barrels with water, added a sack of yellow corn, and two cans of lye. When the kernels started to peel, I took a shovel and scooped the corn into the lake on the north side of the houseboat. Catfish and carp by the hundreds found the corn, with some of the carp running up to 30 pounds, and catfish even larger.

"After a month had passed, another batch of corn was put into the lake. This time I added about 15 pounds of brown sugar for flavor.

"On the south side of the houseboat, I established a square pen made with bales of hay that had been opened, with manure between the layers of dry grass. Three wires were tied around each bale, with a heavy rock for weight. A skin diver went down into the 12-foot-deep water, and stacked the bales, then put one-inch pipes in the center of the pile.

"Next, I piled several green cedar trees over the mouth of the fish refuge. This was for little fish to hide in and attract king-sized crappie and bass.

"What a thrill it was to snag a real big carp with a light line, knowing that the small hook could pull out of the fish's soft mouth. You talk about sweating drops of water the size of green peas, and to hear your heart pounding like a trip hammer on a river piling when the fish come up and roll over like hogs? Or a big blue channel cat? A fellow could get a stroke or something.

"I would like to read something about houseboats in your area, with pictures in color. And I love to read about catfishing."-Erwin Knapp, Villa Ridge, Missouri.

FINEST HUNTING-"I have been hunting in Nebraska eight out of the last nine years. I think your hunting and people are the finest I have ever encountered." — Alfred Glen Thompson, Hitchock, Oklahoma.

ALMOST CONVINCED- "Congratulations to the Nebraska Game Commission on another outstanding success! The Merritt Reservoir trout fishing is unbelievable! Last April, my three daughters, ages 6, 8, and 9, caught their limits of trout in two hours. We didn't see a soul that wasn't catching trout. As for me, I don't fish, but my daughters almost have me convinced."-B. M. H., Omaha.

...THE JUG AND ME

by Steve KatulaA slashed-off jug can't be topped for bailing chore

IT WAS AFTER A late summer rain, and Don Tilman, a construction worker from Hampton, Nebraska, was bailing his small boat at Johnson Reservoir near Lexington. The plastic scoop he was using made fast work of the job. I asked him about the scoop and he said it was part of an old plastic jug cut diagonally across the center. The grip made a dandy handle and I couldn't help wondering what other uses could be found for castaway jugs.

About a week later, I saw a pile of discarded plastic chemical containers in a Lincoln photographic studio. Bruce Oliverious, darkroom technician, told me I was welcome to take them.

I turned on my bandsaw and let my imagination go. I whacked off the top of one container to make a handy funnel for outboard fuel. It looked so darn good that I made another one to keep near my power lawn mower. I duplicated Tilman's boat bailer, and then cut a trap door affair in one jug and rigged up a little latch so the thing could be used as a bait box. To cap it off, I clipped the bottom from another jug to peg to the side of the boat for a lure box.

All these contraptions worked so well that I decided to try my hand at some jugs of other shapes. I went to Lincoln on a scavenger hunt for more raw materials. John Damm, an employee at a dairy, looked at me for awhile before deciding that I wasn't crazy and then offered a suggestion of his own.

"Why not fill them with water, freeze the things, and use them for icing down fish and picnic goodies?" he suggested. "But don't try to drink from them when the water melts: If you use one with a handle like this the hollow grip will collect germs."

I took my new treasures home and got to work. I swiped a big hunk of aluminum foil from the kitchen and then cut out the side of a jug and lined it with the shiny stuff. I filled the jug about a third full of dirt and stuck in a candle to make a dandy emergency lantern that is practically windproof.

My venture took a new twist when I was describing the lantern to my old buddy, Jim Gray.

"Why not fill the jugs all the way up with sand?" he suggested. "I use them for anchors."

I made a mental note to try the anchor bit next time I went out to my pet fishing hole. Also, I didn't rule out the containers for jug fishing to catch big catfish.

Since then, I've made quite an assortment of useful gadgets from old jugs. A pie plate with a hole in the middle placed on top of a jug makes a swell bird bath, if the top of the jug is screwed down to seal the hole. A %-inch hole for a door, and a jug becomes home sweet home for wrens.

There's only one problem I've encountered in all this jug falderal. I'm now afraid to throw one away for fear I'll find some new use of it. I've got boxes and boxes of the darn things, just waiting to be used. Anybody want to buy a used jug?

THE END

NOVEMBER Roundup

It's Big Red on the ground and pheasants in the air as name-your-pleasure month whirls across the calendar. An astronaut comes in for a slice of the funA MONTH OF 30 days, November sparkles with NEBRASKAland activities. The harvest ends, home-town football teams establish almost-end-of-the-season records, and hunters find a pheasant paradise. All these happenings plus some "uptown musical harmony" keep November bursting with events.

With autumn well along, sportsmen flock in to find some of the best hunting in the nation. Opening date for quail is November 10. Another opening date is November 5 when deer rifle season un- veils, but the king of the hunting roost is still the pheasant. This strutting, gamy fellow ranges over 45,000 square miles of Nebraska and provides gunners with sport to spare.

NEBRASKAland's wealth of big game has a bonus in store for hunters. Wild turkey provides many a merry chase for residents and nonresidents alike during an open season that begins on October 29 and runs through November 6. Last year, hunters chalked up 48 per cent success on Nebraska's newest game bird.

Astronaut Neil Armstrong awaits action in the 6th annual one-box pheas- ant hunt at Broken Bow on November 12. Teams from Kansas, California, Mis- souri, Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska compete in this sunrise to sunset hunt. One-box hunting is just what it says. Each five-man team entered is issued one box of shells as it takes to the field. The most pheasant kills registered by a fivesome determines the winner.

Omaha Civic Auditorium buzzes with excitement when antique buyers survey the displays at the Omaha Antique Show November 4 through 6. Attracting thousands, the show is one of the top events in the central states. Known as the World Fair of Hobbies, the Ninth Annual Midwest Hobbyrama features collections from throughout the United States. Scheduled from November 11 through 13, it is staged at the Civic Auditorium. Another Omaha event is the Cornhusker Championship Cat Show taking place on November 19 and 20.

Oklahoma State travels north to meet with the Nebraska Cornhuskers in the last home football game of the season. Kick-off time will mean excitement at the Memorial Stadium on November 12 for Devaney and his crew plus thousands of cheering NEBRASKAlanders. Football galore in this last month of stadium fun sees Omaha U. meet Fort Hayes State for a Homecoming game on November 12. Seward Concordia faces Doane College on November 5 and tangles with Nebraska Wesleyan on November 12.

Wesleyan University welcomes the German Artists Exhibition from November 1 through 27. Other Lincoln affairs include the Lincoln Symphony sponsored Gary Graffman Piano Concert on November 8 and the Singing Boys of Montreal on November 15.

Sheldon Art Gallery, located on the University of Nebraska campus in Lincoln, draws thousands to see its special exhibitions. An array of Lindsey Decker Sculptures and Eugene Felman Prints will be crowd pleasers from November 22 to December 25.

The Collector's Choice Exhibition, which includes regional paintings, goes on display at Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha on November 5. During the third week of the month, paintings sponsored by the Omaha Symphony Benefit are displayed. A Holiday Fair will bring varied intricate designs and patterns to Joslyn Museum on November 3 through 5. Sponsored by the Women's Association of the museum, all the items are sold to the public.

The Omaha Symphony strikes up an all orchestral concert on November 14 and 15.

But, there is more than hunting, concerts, exhibitions, and football games in the state. Thousands will invade Nebraska

(Continued on page 51)WHAT TO DO

1-27 —Lincoln —German Artists Exhibition, Wesleyan University 1-13-Lincoln-"Birth of the Solar System," Ralph Mueller Auditorum 2 —Lincoln —All Star Wrestling 2 — Hastings — Community Concert 3 —Lincoln—Johnny Cash Show —Grand Old Opry 3-5 — Omaha — Omaha University Theatre Production 3-5 —Omaha —Holiday Fair, Joslyn Museum 4 — Lincoln — State High School Advertising Contest 4-5 — Lincoln — Nebraska High School Press Association Conference, Nebraska Center 4-5 - Seward - Student Production - "Tartuff," Concordia College 4-6 —Omaha —Omaha Antinque Show, Civic Auditorium 5 —Rifle deer season opening 5 — Omaha — Collector's Choice Exhibition, Joslyn Museum 5 — Auburn — Nemaha County Hospital Auxiliary Bazaar 6-27 —Lincoln —Twentieth Century Engineering Exhibition, Sheldon Art Gallery 8 — Lincoln — Gary Graffman Piano Concert, Lincoln Symphony 8 —Oshkosh —Soil Conservation Banquet 10 —Opening date for the quail season 11 — Bancroft — American Legion and Auxiliary Annual Smorgasbord 11 — Plymouth — Annual Veteran's Day Celebration 11 —Central City —Veteran's Day Parade 11-13 —Omaha —Midwest Hobbyrama Show, Civic Auditorium 12 —Lincoln —Nebraska vs. Oklahoma State 12 —Lincoln —Kosmet Klub Fall Review 12 —Omaha —Omaha University vs. Ft. Hayes State, homecoming football 12 —Broken Bow —Sixth Annual One-Box Pheasant Hunt 14-15 —Omaha —All Orchestral Concert, Omaha Symphony 15 —Lincoln —Singing Boys of Montreal, Lincoln Community Concert 14-30-Lincoln-"Star of Wonder," Ralph Mueller Auditorium 15-17 —Lincoln —Aqua Plains Water Show, Wesleyan University (Continued on page 51)NEBRASKAland HOSTESS OF THE MONTH

Patricia HolliwayThis NEBRASKAland hostess is not stopped by Nebraska's wind and weather as she journeys through November. Miss Patricia Holliway, daughter of M. L. Holliway of Plattsmouth, discovers the brisk month to be perfect for a bird watching jaunt in the park or an expedition along a scenic Nebraska route. Graduating from Plattsmouth High School in 1965, she is now a sophomore at Fairbury Junior College, majoring in elementary education. Active in campus activities, Miss Holliway serves as vice-president of the Student Education Association and a member of Phi Theta Kappa scholastic honorary. A Sweetheart Ball Princess, her other interests include Navigator's Pep Club and Associated Girl Students.

8 NEBRASKAland

ASH HOLLOW... Windlass to the West

Valley stands as mute testimony of trail's hardship. When plans for restoration are fulfilled, today's pioneer will know ravine's full story by Bob SnowTO THE MODERN traveler piloting his car along U.S. Highway 26 through a ravine called Ash Hollow, the place looks like many of the other small valleys along the North Platte River. Yet this valley, unlike most, guards a history which can easily fill a 500-page book. The only physical clues to its importance are wood and stone markers along the road.

But, only a pin-scratch of history comes to life for those who take time to read the inscriptions. The personal struggles, hardships, and sorrows of those who passed through Ash Hollow on their way West can not be written on markers. Theirs was a dream of hope, and dreams are not written on stone. Cracking whips, creaking wagon wheels, cries of pain, and the solemn words of many a trail-side funeral of a century past still whisper through the valley.

To hear Ash Hollow's tale, stand atop Windlass Hill and look toward the North Platte River.

Deep wagon ruts replace the blacktop road while grazing Herefords become a herd of buffaloes. A pile of family possessions is scattered at your feet because the Oregon Trail is too long, too rough for anything but essentials.

A wagon train lumbers into view. One hundred yards away is its first taste of what it can expect when it reaches the dreaded mountains still far ahead. Some of the wagons are made of expensive hardwoods, and their owners hope they will hold together on the treacherous trail. The poor drive cheap wagons in need of repair. They soak them in the river after each hard day to tighten the spokes in the hubs and swell the felloes so the wheels will not loosen.

A tall, weatherbeaten man with a handle-bar mustache climbs down from the box, strolls to the crest of the hill, and mutters, "So that's Windlass Hill." He rubs his chin, and carefully looks over the steep 450-foot incline leading to a craggy, cedar-covered ravine. Wrecked wagons are strewn below, mute evidence that Windlass Hill can exact a dreadful toll.

He takes out a handkerchief, lifts his hat, mops his brow, then turns, and (Continued on page 55)

Black Bass at Red Willow

by Bill Vogt Lunkers hit gurgling surface lures as father and son match their fishing talents. Largemouth contest proves father still knows best 12 NebraskalandSOMETIMES, A FELLOW gets a certain feeling about a particular place. No matter how far he travels, he always sees it in his mind's eye, inviting him to return. Earl Frost of Arapahoe, Nebraska, feels that way about Red Willow Reservoir, eight miles north of McCook. The 1,700 or so surface acres of Hugh Butler Lake have two arms which embrace some of the finest bass fishing a man can expect. Frost's angling methods are a bit unorthodox, but they are effective. He lugs two motors, one, a regular outboard and the other, a little electric rig. To top it off he uses a fly rod with a spinning reel. Earl has business interests in Arapahoe but he doesn't let them interfere with his fishing.

"I have fished from Canada to Mexico," Earl told his son, Doug, as they pushed off for some early-morning casting, "but I always come back here for my bass. To my notion, it rates as high as any I've ever fished for largemouths. You're going to miss the good times we've had here."

Doug nodded in silent agreement. This trip was important to him, for it would be his last at Red Willow for a while. Just out of the service, the 27-year-old was looking forward to setting up a private dental practice in Colorado. The younger man looked at the glass-smooth water, still misty as the May-morning chill resisted the warmth of a rising sun. He realized now that he shared his father's feelings about the impoundment. Both men were fairly sure they would catch fish, considering it largely a matter of time before they were onto the good ones.

Speaking above the noise of the engine, Doug pointed to a promising bay.

'What say we start there and work our way clear back to the end?" he asked.

Earl guided the craft through an obstacle course of trees and cut the engine while the younger member of the team tipped the tiny electric outboard from its bracket on the side of the boat. Moving as though pushed by a breeze, the boat glided toward a clump of surface weeds. A bass would be hard put to detect any danger from the quiet approach. The elder Frost lifted his eight-foot fly rod from the seat beside him. The rod was rigged with a closed-face spinning reel and six-pound-test monofilament instead of the usual fly line and reel. The fisherman tied on a rubber-skirted popping plug, tripped the line release button on the reel, held the line in his left hand, then gently flipped the lure into the weeds. The plug stopped within inches of the foliage, right on target. Earl let the popper remain motionless until the rings disappeared, then twitched it. With an audible gurgle, the surface lure moved a few inches. A couple of similar maneuvers failed to produce any results, so the Arapahoe man looked at his son and jerked his head toward a protruding stump. Doug laid aside the standard spin cast outfit he was rigging and started the quiet motor to send the boat within casting range of the stump.

"Funny thing," Earl remarked as he cast, "how these bass just don't seem to be interested after the first couple of twitches. I figure that if one doesn't hit the first two times I jerk it, I might as well haul it in and cast again, though I have seen a few grab a plug on the reel in."

Doug tied on a frog-finish lure similar to his father's and sent it flying toward a line of weeds.

"Yes, and I don't see why the plug has to be placed right up against the weeds, either. A few inches away, and it's no go. These bass must be lazy critters with all the natural feed around. The place is lousy with bluegill."

The dentist twitched his lure once, and it disappeared in a vigorous swirl of water.

"How about that?" he asked, rearing against the bend of his spinning rod. Earl laid down his own outfit and reached for the net. He looked on anxiously, offering advice: "Did you set the hook solidly?" and "Seems like you can't set a barb too hard on these babies."

Doug answered, "I almost broke his jaw, I set it so hard, but I'm afraid he's going to wrap my line around that stump and get away, anyhow."

But the dentist prevailed and turned the fish's run. The bass cleared water and slammed back with a head-shaking surge. Doug brought the tiring gamester to Earl's waiting net, and his father raised the squirming fish. The ex-serviceman untangled his lure while Earl put a hefty 21/2-pounder on a stringer.

"I lost one just when yours hit," Earl said. He rationalized, "I believe that a bass fisherman who gets 30 per cent of his strikes is doing pretty well. Now, there should be one right up against that big snag at the mouth of the inlet."

Doug's cast was the first to reach the snag, but nothing happened. His lure raced through the water as he cranked his reel in disgust. Suddenly, a fish who decided to be the exception that proves the rule slammed into the fast-moving gurgler, then let go in the next instant.

"Whew, that doesn't happen very often," Earl grinned. "Kind of rough on a guy's nerves, isn't it?"

"Do you think maybe he'll come back?" Doug asked.

"No, you stung him," his father answered.

"No, he stung me!" the son countered.

As the boat glided noiselessly into a thick cluster of trees, a couple of bank fishermen looked up from their casting. Apparently it took a while before it registered that the "drifting" boat was being pushed by a tiny electric trolling motor.

Earl nodded toward shore, commenting, "It won't be long now until bank fishing will be out in most of the bays and way back up each arm. Another 30 days or so, and this whole stretch will be pretty well closed off with moss."

On Doug's suggestion, the pair hoisted their little

motor, cranked up the big one, and zipped back to the

main lake, heading for the other fork. The boat

NOVEMBER,1966

13

rounded a point, and the dam face came into view. A

couple of boats were working slowly along the structure,

probably trolling for walleye and northerns. A

lone water skier cut a white wake behind his speeding

tow boat, but not many people were out. The sun was

already burning high and hot, but the Frosts were set

on giving their lone bass some companionship.

rounded a point, and the dam face came into view. A

couple of boats were working slowly along the structure,

probably trolling for walleye and northerns. A

lone water skier cut a white wake behind his speeding

tow boat, but not many people were out. The sun was

already burning high and hot, but the Frosts were set

on giving their lone bass some companionship.

Hugh Butler Lake's west arm is longer than the one to the north, but part way up its length, it disintegrates into an impenetrable bay. But like the north stem, it contains many enticing little bays and cutbacks. At least, the Frosts think they are enticing. Both men should know, for they have taken a pretty impressive tally of largemouth and smallmouth bass there.

Today it was a different story. The bass were either on a hunger strike, or were taking a live-let-live attitude toward the poppers. The Frosts stubbornly refused to change to subsurface plugs, and for a couple of hours, contented thmselves with one fish too small to keep.

"I guess that three years from now, we'll be getting more variety in sizes of fish," Earl speculated. "Most of the bass of any size that I've caught out of this lake so far look as though they were poured from the same mold. The initial stocking can't last forever, but there will always be some big ones around. It will just take a little more patience to catch them!"

Doug nodded. It was one of his father's favorite themes: have a little patience, and you'll generally come back with fish; that is, if you stay at it long enough. The theory works, because Earl seldom comes back skunked when he takes on Red Willow's bass. The veteran angler leans heavily toward the rubber-skirted popping plugs, though he uses a fly rod popper when conditions are right. In addition to the freak spinning reel-fly rod outfit, Earl also keeps a level-wind rig ready to go.

It was nearly noon before the fish decided to co-operate. The first sign was a swirl at Earl's plug. He retrieved, then cast again. Second time around, a bruiser bass inhaled the object of his annoyance and took off for parts unknown. Earl's fly rod flailed air as the bass began the grim tug of war. Earl countered every frantic rush and desperate leap and the fish slowly lost ground.

A stringer with two fish on is twice as satisfying as one with a loner, and the father-son duo went at it again with renewed energy. Instead of a series of desultory casts, their fishing became a contest.

"There should be a fish just off that little point," Earl said, casting to a narrow spit of land.

A big-mouthed bass bore out the speculation by chomping down hard on a mouthful of treble hook. Reveling in the heart-stopping fight, Earl wound the fish in as fast as his unwilling catch would allow.

"You're starting to call your shots, and that's a bad sign," Doug joked, netting the fish.

14 NEBRASKAland"I'm two up on you," the older man jibed, "I guess you got a little soft in the service, with nothing to do but stand around pulling teeth."

Doug started to answer, but found himself in a watery wrestling match with another finny contender. Deciding to let his success speak for him, young Frost eased the fish toward the boat.

"Now I suppose you'll keep me so busy untangling your fish from the net and putting them on the stringer that I won't be able to strut my own stuff," Earl muttered through a false frown.

"Well, it's been a long dry spell for us," Doug answered, "I've got to make the most of it. I'd hate to have you beat me too far, because that would be downright embarrassing."

By this time, the boat was at the end of the navigable part of the arm, and the clear water was giving way to green scum punctured with protruding stumps. A wake cut a trail through the algae.

"See that bass chasing a minnow? Let's go get him," Earl suggested.

Doug guided the boat with the electric kicker, cut the motor, and then cast directly into the pale green ooze. A bass plummeted skyward, slapping the lure as though with a fist. But Doug set the hook on empty air, and his savage jerk backtracked the plug several feet.

"Boy! He sure spit that one back in a hurry," Doug moaned.

"Well, easy come, easy go," was the only consolation he got from the other end of the boat.

Swinging across the narrow neck, the two plug casters started working back along the other side. Intimately familiar with each cutback and cover, Earl pointed to scenes of past successes, gently flipping his plug with pinpoint accuracy. It wasn't long before he added another pair of bass to a growing stringer. Not to be outdone, Doug redoubled his efforts, placing the boat so both casters could work at once. A nice bass cleared the water and came down on top of his plug, and the fight was on.

"I'll catch up with you, yet," Doug gritted, working the fish into the net.

Earl smiled and nodded with a "sure-you-will-but I-don't-think-so" look on his face as he plucked at the landing net, disengaging a pair of treble hooks. The older man looked up from his work and scanned the now-widening part of the old creek bed. Only two other boats were in sight, and both of those belonged to bait fishermen. It was hard for Earl to believe, after a few years of good fishing at Red Willow, that the area once was known more for its carp and bullheads than for its game fish.

Red Willow was the first Nebraska lake of major size to be rotenoned and restocked with game fish. It was also the first fish rehabilitation effort in the Missouri River Basin to be (Continued on page 51)

NOVEMBER, 1966 15

HER NAME IS BARBARA

My better half's challenge leads us to a mixed-bag marathon. At end of hunt, one picture is worth a thousand wifely words by Gayle JohnsonI WENT SIX feet straight up at the blast of Barbara's 20 gauge. For an instant I though she had decided to collect my insurance the quick way.

'What in the--------?" I sputtered, trying to regain my aplomb.

"Didn't you want me to shoot that squirrel?" my wife inquired with an impish smile.

I looked around and there was a plump fox squirrel kicking his last in the dry leaves under the cottonwood. It took a couple of seconds for things to register. I had been resting under the tree, waiting for my wife to catch up and didn't know the squirrel was above me. Barbara had seen him and lowered the boom to startle me gray.

Barbara and I, along with my brother-in-law, Larry Spurling, were on a mixed-bag hunt around our hometown of Ong, Nebraska. It began one November day when Barbara and I were talking about Nebraska's marvelous small-game hunting.

"We have quail, pheasant, cottontail, squirrel, and waterfowl in a 25-mile radius of Ong. Limits are relatively easy to come by," I said.

"I don't buy that easy limit bit," my wife argued.

"Maybe, if you're lucky you can bag one of each specie in a day's hunt but that's a collecting expedition, not a real hunt."

"And what is your idea of a hunt?" I asked.

"A day when you see plenty of game, get enough shooting to keep it interesting, and bag a satisfactory amount without wearing yourself to a frazzle," she replied.

As a former school teacher I appreciated my wife's skepticism, but I had to stand by my convictions.

"I'll bet you I can bag a limit of everything in one day," I challenged.

Thinking of the job she would have cleaning and preparing all that game, Barbara relented a bit. "Tell you what. You get Larry and we'll spend a whole day in the field and if among us we bag seven or eight quail, a half dozen pheasants, a couple of ducks, a few cottontails, and a squirrel (Continued on page 53)

Wild water at Rocky Ford is good prep school for filing down the Snake River

Danger, excitement run high as Ray VandeKrol and I bait a wild river

18 NEBRASKAlandTAMING THE SNAKE

NOVEMBER, 1966 19

Sandwiched in by a cliff, Roy and I make our portage around Little Falls

THE SHOUT OF "rock, dead ahead" came almost too late to avert a disaster, but with all the strength I could muster, I tried a draw stroke to pull our craft away from the boulder but I was too late. A protruding rock thumped against the aluminum sides of the canoe and spun it around. Almost before I knew it we were shooting the rapids backwards.

Bowman, Ray VandeKrol, feverously dug his paddle into the turbulent belly of the Snake River to right the craft. If the tough old river had its way we would be swimming the white water instead of riding it. It seemed like an eternity, but actually it was only a few seconds before we regained control of the craft and headed the right way.

The Snake River has the personality of its namesake. It's temperamental, mean, unpredictable, and sly. Yet, it's beautiful. My first encounter with the Snake had occurred eight months earlier when I was the first, to my knowledge, to conquer the 23-mile stretch of white water between Snake River Falls and the Niobrara River, but the river took its toll that day, too. On that float four canoes started the trip. One was wrecked within the first 100 yards, another had a big hole knocked in its side, and although my lead canoe came through undamaged, my paddling partner and I got a taste of the Snake's venom. The fourth canoe made it but it took considerably longer to run the river than my craft.

On this trip I planned to make a clean sweep against the rampaging river. The only water I wanted to feel was the spray that leaped over the gunwales. The only damage to the canoe, I hoped, would be scratches from windfalls which dotted the channel.

The two of us came prepared to meet the river on even terms. A day earlier, Ray and I drove from our homes in Lincoln to Rocky Ford, a wild stretch of water on the Niobrara River, to make a few practice runs. Teamwork is a must in canoeing, and we felt shooting the rapids at the ford would help develop our timing. We did our share of swimming that day as the craft tipped over once, and swamped once. But even with the dunkings we felt we could tame the Snake.

Ray has four years of canoeing experience. His first cruise took him from Nebraska City to the Gulf of Mexico. An ardent canoe fan for almost 10 years. I received my first taste of the sport while in the Boy Scouts. Ray and I had paddled together in several races including a 250-miler in Canada. I keep in trim with weekday paddles on Holmes Lake in Lincoln where I own and operate a marina. Although we didn't expect to shoot a 20-foot fall and have our shoes and shirts ripped off as we did in that disastrous Canadian ride, we did expect some trouble on the Snake.

The upper reach of the Snake, down to the falls, is relatively open, with no deep canyons of consequence. Its current is somewhat swifter than many Nebraska streams, but it offers little challenge. We wanted to try the faster currents below the falls. That is where the river sheds its lethargy and becomes a hissing, writhing embodiment of its name.

Ray got his first real view of what Nebraska's white water serpent held for us when we carried the canoe down a steep incline to where we embarked, I could see the surprise on Ray's face as he studied the 20 m.p.h. current.

Before the run, Ray and I contacted all ranchers who owned land along the river. The waters are public, but if for any reason we had to go ashore, we would be trespassing if permission was not obtained.

All the ranchers were more than

willing to give us permission, and

ranchers Betty and Les Kime offered

to serve as hosts before and after

the float. As we pushed out into the

rapids, we were impressed by the

surrounding beauty but before we

could actually enjoy the towering

cliffs with their Ponderosa pine-studded rims, we were whisked away

on the powerful river. In order to

NOVEMBER, 1966

21

control the canoe we had to build up

our speed so we were traveling faster

than the current.

control the canoe we had to build up

our speed so we were traveling faster

than the current.

It wasn't long before both of us learned why the river is named the Snake. It seems as if every 50 yards or so, there is a right-angle turn as the river weaves its way through the canyon. Every corner is blind and in a brush-choked river with plenty of windfalls and rocks, it didn't take us long to learn why so few succeeded in making the 23-miles.

Every turn holds a new adventure. The only clue to what waits beyond the next bend is the sound of rapids. If a tree has lost is anchorage and fallen into the river, or if several rocks jealously guard the passage, the water rushing over the barricades can be heard for about 150 yards.

We soon found that it takes more than just keen hearing to make it down this river. An essential to navigation of the Snake is a knowledge of how to read its ways. Once out of the main current, the river will carry you where it wants to. If you want to run the river, it is necessary to stay in the main channel. As the canyon walls flashed by, it took all our combined experience to study the current and the lay of the land to determine the winding channel.

We hit a 175-yard straight stretch and Ray pointed to a lone buck standing in one of the relatively few meadows along the river bottom. While we were admiring the deer, we were suddenly shaken back to reality by the sound of water running over some sort of barricade.

As we rounded a bend a barbed wire fence across the river knotted my stomach with fear. Both of us automatically thrust our 9-inch blades into the river in a series of quick draw strokes to escape this peril. In a matter of seconds, the canoe was almost parallel to fence as we struggled to get out of the main current.

We sweated, strained, and sweated some more to move out of the channel, hoping the craft wouldn't roll. I thought I knew every major barrier on the river. But my first time down the rapids, Merritt Dam must not have been guarding its water so jealously, and evidently we must have skimmed over the top strand of the then-submerged wire without noticing it.

Neither of us had had any experience in climbing barbed wire in a Whitewater river. But instead of going ashore and carrying the canoe around the object, we decided to try the water route. As I held the canoe steady, Ray carefully eased himself up on the fence. With just an inch or two to spare, I guided the bow under the fence and Ray lowered himself back into the canoe. Then it was my turn. As Ray held the canoe in place, I played andy-over, and climbed the fence.

With low water, I had just about decided this trip was not quite as rough as the first. During my first run we shot Little Falls purely by accident, mainly because we didn't see it until we were almost over it. This time, I thought, the low river would make us carry the canoe around the falls.

Ray and I waded out on the lip of the falls and stared at the whi water we had yet to travel. A litti disappointed that we could not make the shoot, we decided that as long as we had to portage, we might as well take a break.

While sitting under a tree, Ray muttered, "I wonder what would have happened if we had hit the fence or rolled when we hit that rock."

I was almost afraid to answer. In a river running between steep canyon walls and in a land that seemed like a wilderness, evacua- tion of an injured man could be tough.

"I don't know. But if we should roll, the best thing to do is hang on to the canoe. The white water will carry you away if you don't. Come on, we've a river to run," I answered.

When we shoved off for a second time, the Snake grabbed us and moved us closer to the wedding of the two rivers. Below the falls our strokes must have hit 60 a minute as we fought once again to build up speed.

As we paddled down the fastest river in NEBRASKAland, I wondered if we might not make it though without an accident. This river is not for the amateur canoeist, but for adept canoemen the trip is a wonderful and challengeing experience.

The terrain told me we were getting close to the Niobrara. But, I said nothing to Ray. This was his first trip-let him discover the Niobrara.

As we neared the big river, a mink slipped into the water and headed downstream. Soon we were paddling side-by-side with the furry creature. Finally, we rounded a bend and the merge of the two rivers met our eyes: Suddenly, we realized how tired we really were.

We had beaten the Snake at its own game. Someday, we would try again and the river might beat us but I knew we had to try. For the tumultuous Snake is like its namesake. It has a fascination that cannot be ignored.

THE END 22 NEBRASKAland

Pershing AND THE POACHER

A reader recounts brush with AEF leader during lake-country hunt. Memory of incident is as bright today as it was then by Edward GrimesTHE YEAR WAS 1922. Warren G. Harding was in the White House. The "big war" in Europe had been over for several years, but General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, was still very much in the minds and hearts of all Americans. Prohibition was in force, and the "Roaring Twenties" were just getting up a full head of steam.

Such things were far from our minds, however, as my pal, Vernon "Rat" Sandy, and I sped through the Nebraska prairie to the Sand Hills. We had Rat's cut-down Model T sagging with hunting, camping, and trapping gear. The September sun glowed as we headed from our farm homes near the Platte River in eastern Nebraska toward the lakes around Valentine and Wood Lake. The air seemed to vibrate with excitement 24 NEBRASKAland as we zigzagged up the lush Elkhorn Valley toward Cherry County. We had heard glowing stories about the heavy-furred muskrats that prowled the Hills.

On September 9, we arrived at our destination — the Deke Tetherow ranch, about 18 miles west of Wood Lake. Deke greeted us with his customary warmth and friendliness, a trademark of most folks who lived in the area. I would stay with Deke, while Vernon would stay with Deke's brother, Sam, who lived just half a mile across a lush valley meadow. We settled down to await the trapping season.

We were just 22 and, like most farm boys, had learned to hunt, fish, and trap early. Still, we had looked forward to this trip for several years. As the time to go drew closer, we had talked about nothing else —it was a dream come true.

We waited impatiently, but kept busy. Vernon and I helped the Tetherows with those chores that all ranchers must do before winter comes. We helped repair buildings and fences, hauled coalby four-horse team from Wood Lake, gave Sam a hand with vaccinating his calves, and in our spare time, scoured the Hills on horseback looking for skunk and coyote dens and explored the surrounding lakes and marshes.

One evening, as we cruised in the Model T, we passed the southeast arm of Red Deer Lake. We spotted some ducks feeding close to shore, and I asked Vernon to stop so I could "make a sneak" and maybe bag a couple of quackers for the table. Neither Deke or Sam did much hunting, so we usually kept the larders well supplied with game while we were there.

It was an easy matter to crawl within range and drop a pair of fat mallards. As I was wading leisurely back to shore with ducks in hand, a car came barrelling down the road. The driver braked to a sudden stop between me and our car, leaving a cloud of dust.

"There is no hunting allowed on this lake," he hollered as he tumbled out of the car.

"Why?" I asked in surprise. "We've shot here before, and there aren't any signs anywhere."

Very few lakes were posted in those days. Ballard's Marsh, Hackberry, and Marsh lakes were exceptions, since some commercial facilities exsisted on them. And, of course, the long haul from the cities discouraged all but the most hardy waterfowler.

"This lake is reserved for General Pershing and Charles Dawes," he explained. "They are hunting grouse, but I expect to see them any day now. Tramping these hills will make duck hunters out of them mighty fast."

The man was overseer of a nearby ranch and was keeping a watchful eye on "Pershing's lake". The General and Dawes, who would later become vice president, had come to Nebraska's Sand Hills that October in 1922 for a rest and a go at the excellent grouse and duck hunting.

Rat thought I was feeding him a line when I told him what had happened at the lake. He still didn't quite believe me when we were driving back from a ranch the next day. Suddenly, we came on a car stalled in a low saddle between two towering dunes. The driver flagged us down. Eager to put his mechanical know-how to work, Rat offered to lend a helping hand. Rather than stand idly by, I hauled my gun from our "sand buggy" and headed up the shady side of the nearest grass-covered hill, hoping to flush a "chicken" or locate a skunk or coyote den.

A long time before, I learned that the easiest way to reach the top of these slippery hills is by a long diagonal in easy stages. I was only about 200 yards from the cars and still well below the crest of the choppy, when a grouse sailed over the top and slanted toward me. He veered off slightly when he saw me, but it was too late. I dumped him just as another bird flew over the hill from the same direction. I nailed him, too, with a puff of feathers to mark the spot where he and an ounce of No. 6's met.

I picked up the two plump grouse and resumed my walk. Just then, a man came striding over the ridge where the chickens had appeared. That explained why the birds had soared over the hill into my gun. The chickens had been hiding in the grass close to the top of the choppy and flushed as the other gunner approached. They had lost no time in trying to take refuge on the opposite side of the hill before the other hunter could get off a shot. The same thing has happened to me many times, and unless there is another shooter on the other side the bird usually escapes.

Something about that approaching hunter looked vaguely familiar, even at a distance. As he drew closer, however, I could distinguish his closely-clipped military moustache. I knew immediately that it was General Pershing himself. As the famed AEF commander neared, I shook with excitement and confusion.

My anxiety disappeared as Pershing smiled. "Well," he said, "I guess we'll have to make a change in our strategy. They sure got over that hill in a hurry."

I managed to find my voice long enough to ask, "You are General Pershing, aren't you?"

He nodded and continued, "I'm glad we are going to try for ducks tomorrow. These hills get steeper every day."

We turned to head back to the cars, and I told the General about my fondness for duck hunting. Encouraged by his friendly interest, I told him about my "poaching" ducks on "his" lake the day before. To my amazement, he only chuckled and invited me to be his guest and shooting partner the next day at Red Deer.

I was at the lake bright and early, and the memory of that morning's shoot remains vivid and clear, as clear as the General's farewell remark as we parted company in the twilight of that autumn evening 44 years ago.

"Ed," he said, "you shoot extremely well. I'd much rather you'd shoot as a guest on my lake than as a 'poacher'."

THE ENDOUTDOOR NEBRASKAland proudly presents the stories of its readers themselves. Here is the opportunity so many have requested —a chance to tell their own outdoor tales. Hunting trips, the "big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor impressions— all have a place here.

If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, OUTDOOR NEBRASKAland, State Capitol, Lincoln 68509. Send photographs, too, if any are available.

THE SETTING SUN

photographs by Lou Ell, Gene Hornbeck, Dave Becki, and Charles Armstrong Catastrophe to clear weather, man reads destiny in evening sky. Too dazzling at noon, burning ball relents at dusk. Even then, it is mystery to mortal eyesVIVID BANDS OF RED stretched across Nebraska's western horizon as the day bled itself dark. The sodbuster headed his team home, lines draped over his shoulder. The early evening chill turned the farmer's sweat-soaked shirt into little icy prickles, but he didn't notice the cold as he raised his eyes to the sunset. For months now, everyone had been talking about the brilliant colors which appeared at each day's end. No one had come up with a satisfactory answer, if there was one. News traveled slowly in 1883, but the farmer had heard of a volcanic eruption in Indonesia. He and his neighbors did not realize that they were watching a blood-red epitaph for the 36,000 souls who died in a tidal wave set off by the explosion.

Dust and ash from that August 27 disaster rose 50 miles into the air as the volcano that once was Krakatoa, or Krakatau, sounded off with a blast that was heard and seen 2,000 miles away. High above the Nebraska farm, volcanic debris was orbiting the earth, causing gorgeous sunsets all over the world well into the following year.

Beautiful sunsets are not always built on catastrophe, however. Normal atmospheric conditions routinely contribute to an assortment of colorful and strange displays. Science can explain what makes a sunset tick, but it cannot tell what there is about the day's final moment that makes it magic. All the world seems suspended in a brief salute to the dying day. Time stands still as a boat is silhouetted against a backdrop of crimson on Lake McConaughy. There is something poignant in an uprooted tree trunk tilting black against the sky, a dead reminder of many days which have gone before. Sunsets know no place. Their only requirement is a horizon, and admission is free.

Long before man's curiosity led him to explore the why and wherefore of sunsets, the spectacle led him to revere the sun and its daily course. Ancient Egyptians had their sun god, Ra. In old Greece, citizens claimed Apollo was driving his fiery chariot over the horizon. Indians from the Aztecs and Incas to those of the Nebraska plains looked at the sun with reverence as they soaked up its warmth. To the Sioux, the sun was a test of courage. In the tribal sun dance, a brave would cut two incisions, one on each side of his chest, and pass a thong under the skin, while the free end was tethered to some heavy object. All day, the brave danced against the searing pain, staring at the eye-searing sun until the thong tore loose to complete the brutal test. Apparently such gruesome dramas usually ended by sunset, for there is no record of such an ordeal being called on account of darkness.

Op or pop art can't hold a brush to beauty of evening

A burning orb, so bright at noon that it makes less

hardy humans turn their eyes away, the sun

relents in the evening, and permits every one to

gaze at it. Though it is the largest of the readily-visible

stars by appearance, the sun is actually an average

star in the galactic myriad. Its nearness to earth

creates the illusion of bigness. A closer look at the star

with the naked eye is possible in the evening because

its rays are traveling through more of the earth's

atmosphere between the source and the observer, dissipating the glare. This is the time when many of the

sun's phenomena become visible to the naked eye. A

close scrutiny may disclose sunspots as darkened

specks on the blazing surface. These are literally magnetic disturbances of immense proportions. The sunspots are cyclic in their behavior, swelling to peak

numbers, then declining in activity every 11 years.

Sudden outbursts of magnetic energy, or flares, accompanying sunspots exert an atmospheric influence

so great that it is felt on earth. During periods of peak

NOVEMBER, 1966

27

sunspot activity, magnetic compass needles may act

up, and radio communications tend to become erratic.

sunspot activity, magnetic compass needles may act

up, and radio communications tend to become erratic.

Ice crystals and water droplets in the upper atmosphere play a bagful of spectacular tricks with sunlight, often at sunset. A whole series of suns on the horizon does not mean the end of the world. It is only a few sun dogs, or mock suns. These are illusions created by the structure of suspended ice crystals. Related phenomena include halos, crosses, and shafts of light. Man reads all sorts of meaning into the sights.

Raindrops also add their bit to the heavenly show. The rounded drops disperse rays of light into the brilliant arc we call a rainbow. These are most easily visible when the sun is at a low angle to the observer, such as at sunset. The bow is actually a circle of the colors of the spectrum, with the center exactly opposite the sun. The observer sees only a many-hued arc, the colors of which are influenced by the size of the drops. Smaller moisture particles tend to blend the colors, with orange and pink predominating. Larger drops bring out the stronger reds and violets. There is no pot of gold at the end, but a rainbow is its own reward.

Colors in the sunset itself are influenced by a number of things in the atmosphere. If the air above the earth wasn't cluttered with an accumulation of bits, particles, and drops, sunset as well as sunrise would be a dull affair, quite colorless and abrupt. Color is described in terms of wave lengths. Blue has the shortest and red the longest of the waves. The blue waves have difficulties in penetrating the particle-laden air and are sent flying in all directions, making the sky blue during the day, obscuring the ever-present stars. Red waves fare better, pushing through the atmosphere without becoming disassociated from their source. The effect is a spectacular blend of red and orange which sparks the sky with splendor as the sun dips below the horizon.

During very clear weather, the last sight of the setting sun might be a bright green, a trick of refraction in the dense lower layer of atmosphere when the red end of the spectrum is bent below the horizon. Other times, the red rays may predominate in a bright flash of crimson. Smoke and dust particles from a great forest fire can cause a bright blue or green sunset.

Before the white man came, Nebraska's sunsets were often tinged with the dust of mighty herds of bison. Only Indians were there to thin the countless numbers of the animals, and they killed only to meet their own needs. Not so with the white man, however. When he came to push Indian and bison from the scene, he brought with him a new kind of sunset.

Scratching a living from the tough prairie sod, the settler cleared, burned, and plowed to plant his grain. In 1874, a new cloud stretched across the sunset: a living cloud of grasshoppers. Millions of the pests settled, rose, and settled again, destroying all vegetation beneath them. Some settlers reported that they could see no sunset at all through the hordes of whirring insects. In the mid-1930's, another tragedy could be read in the evening sky. Lack of rain gnawed at the nation's vitals, and farming came to a near standstill in Nebraska. Huge dust storms rose from the parched ground, and again the sun's fading light was tinted with dust, to a much greater extent than it was by the bison. Colors varied with the wind, as red dust from the south mixed with the grays of the Prairies. Sunsets were beautiful but no one missed them when the hoped-for rain clouds blotted them out in drouth-breaking downpours. Now that the evenings of catastrophe have ended again, Nebraska's sunsets smile on a land of promise and plenty as the seasons roll on with their ancient regularity.

Winter, with its sharpened, almost rarified air, catches the fading red rays on fields of snow. Long shadows trace dark fingers through the reflected pink, and gaunt trees stand out in bold relief. Summer's crystal waters now run leaden and inscrutable in places where there are cracks in their icy light-reflecting armor. Winter is a time when sunsets touch the ground.

When ice becomes water, spring sunsets bring ominous thunderheads, pregnant with rain. The moisture shows black because sunlight cannot penetrate the clouds. Shafts of light stab downward between the breaks as though the sun were trying to force itself on the greening earth. In turn, the plants either reach toward the sun, or recoil from it, depending on their natures.

Some plants even follow the sun on its daily rounds during the long summer months. A young sunflower, for example, remains at right angles to the sun, facing according to its movement. This turning toward light is called phototropism. It is caused by changes in concentrations of plant hormones, or auxins, and by differences in the rigidity, or turgor of cells.

Daylight and the invisible ultraviolet rays accompanying it are vital to a plant's growth. In the fall, as each succeeding sunset takes a bigger bite of the hours of light, the time for growing ends. As the vegetation withers, leaves are transformed into dazzling reds and yellows. This is the only time of year whQn the earth is dressed to match its sunsets, and the two vie with each other every evening.

In twilight of their years, angling duo takes time to admire gradeur of sunset

Astronomers are shutterbugs at heart and have come up with some gadgets and tricks of their own to photograph the sun. Most notable are the spectroheliograph and the coronograph. Man learned early that many effects of the sun become apparent when it is in eclipse. A coronograph creates the illusion of an eclipse freeing the sun's outer layer from the all-concealing glare. A spectroheliograph photographs the sun in one color, bringing out otherwise invisible details. Remarkable photographs have been taken through telescopes when scientists linked the new tools to special cameras.

Man is learning just how much he does not know about the sun, but this knowledge is building. A gaseous veil called the photosphere is all he normally sees. Deep inside lie other layers of gas, down to a center that is denser than steel. This monstrous cauldron may be as hot as 50 million degrees Fahrenheit. It would seem that such a fire could not sustain itself indefinitely, but estimates of longevity claim the final sunset is billions of years away.

When the sun is blanked out artificially with a coronograph, or during an eclipse, its atmosphere peeks around the edges of a dark circle. Flares may be seen streaming out like huge tails. These are luminous gases shooting off into space. The surface of the sun appears as an ever-changing granular texture, with everything in motion at once. It resembles shifting grains of rice.

Since earliest times, the swirling sun has attracted man much as a flame attracts moths. A big slice of modern technology is devoted to placing man nearer and nearer to what Shakespeare called the "burning eye of heaven".

Some Nebraskans are blessed with an opportunity to see the sunset from a vantage high in the atmosphere. These are the pilots, whose craft glint in the sun after the surface below is already plunged into evening darkness.

A relatively early effort to put man on a heavenly footing took place in 1934, and its abrupt but not tragic conclusion took place on a Nebraska farm. In a joint effort of the U.S. Army Air Force and the National Geographic Society, three men attempted a record balloon ascension from Rapid City, South Dakota. The three, Captain Albert W. Stevens, Captain Orvil A. Anderson, and Major William E. Kepner, escaped with their lives via parachutes as their torn balloon plummeted from nearly 61,000 feet into a field near Holdrege, Nebraska. Two of the men, Captains Anderson and Stevens, made a second try the following year, and reached an altitude of more than 72,000 feet. The two men made a soft landing on their return, but not before they got an impressive view of the horizon. They described it as fuzzy white, with blue, then black sky above, stretching toward perpetual night.

In 1962, Astronaut John Glenn saw an even more spectacular sky as he soared aloft in Friendship 7 to travel over 83,000 miles. Glenn reported that seen from high altitudes, the earth slowly darkens as evening approaches, and the sun is distorted into orange, red, and then blue before slipping into darkness. The man in space was treated to a quartet of sunsets in a single day. From his staggering height, Glenn could also distinguish cloud cover over parts of the world.

Though an astronaut's earth-bound contemporaries can only look upward, the mere sight of a sunset still rewards the observer. Clouds do much to enhance a sunset, breaking up the expanse of sky and reflecting the colors. Primitive men often read their fortunes in cloud formations against a dropping sun. Imagination saw whole battles unfolding in the churning masses and in some instances the huge cloud faces seemed about to speak. But great events were not the only omens observed. Some men even predicted weather from the clouds wafting across a reddish sky. Some of the theories endured, despite the objective probings of science. For example, there is some truth in the sayings; "Rainbow at night, sailor's delight", or ? Red sky at night, shepherd's delight". Under certain conditions, such displays really are indicators that clear weather lies just ahead.

Clouds for the sky observer to ponder are of several different types. Highest of the lot is cirrus, a feathery formation which occurs above 20,000 feet. Strands of cirrus, called "mare's tails", are generally associated with a period of fair weather, perhaps followed by the approach of a front. When cirrus clouds begin to get friendly with each other and build into denser formations, bad weather may be on the way. Clouds with the prefix, "alto", spread over a middle ground of about 6,000 to 20,000 feet. Stratus clouds are layered, anywhere from the ground up into the cirrus altitudes, where they become cirro-stratus formations. An alto-stratus formation may appear as a semi-transparent cover. When it begins to dim the sun, and continues to thicken, precipitation is a distinct possibility.

Alto-cummulus, another middleground formation,

may build cloud towers containing rain. If the sunset

is visible behind them, though, it's probably a false

alarm. Stratus clouds are low-altitude blankets which

sometimes lower to become surface fog. Cumulus formations range from fair-weather puffballs to churning

thunderheads. Clouds by themselves are no sure-fire

weather indicators, or even the most amateur of

weather prophets would never be wrong. A long list

of ifs, ands, and, wherefores also enter into an accurate

forecast. Such things as wind direction, location of high

and low pressure cells, humidity, barometric pressure,

and stability of the air masses play very important

NOVEMBER, 1966

33

parts. Meantime, it is often fun for

an average observer to try to second

guess the weatherman; doubly so if

he is successful.

parts. Meantime, it is often fun for

an average observer to try to second

guess the weatherman; doubly so if

he is successful.

Weatherman, scientist, soothsayer, or just plain curious, each person with an eye on the sun has his own reasons for looking, and the looking is at its best in the evening and in the morning. No one knows all the answers, and so far, the big ball of gas just isn't talking. It is no wonder that the sun found a place in the world's religions, for it is tied up in so many things that affect the earth and its never-ending, interacting cycles.

Man may photograph, analyze, and speculate about the sun, but in the final analysis, it remains untouchable and remote in the broad sweep of interstellar space. As science pushes farther and farther into the frontiers of space, man's aspirations go higher and higher. The moon, and perhaps Mars will one day feel his footsteps, but never the sun. Each day, the earth rotates, bringing with it the sunrise, or as Homer put it in his Iliad, "Rosy-fingered Dawn".

Morning begins with a fanfare of i color as night leaps eagerly into daylight. But evening comes with a quieter step, burning like a fire that does not want to die. The world's disasters are sometimes remembered by their sunsets, but there is a glory there as well. Blazing with the force of nuclear explosions, the setting sun salutes the countryside with a glowing goodbye, promising to rise on the morrow with colors equally as fine. But there are other lands over the horizon, stretching impatiently at the end of a long night. For one man's sunset is another man's dawn.

If one day, the red telephone rings and enough buttons are pushed, th§ sky will cloud with the debris of a million Krakatoas. The strickened earth would throw up a screen of dust to hide its shame from the sunlight. But, one day the dust may settle enough to let the ball of crimson fire look through. Eventually, the earth would know the sun again, but its settings, more beautiful than any man has ever seen, would bleed bright red on a million empty days.

THE END

Ice-shackled Merritt Reservoir borrows an alien warmth from blazing fires above

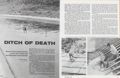

Ditch of Death

Ainsworth Canal yields grim data on deer. More will die until Sand Hills booby trap is disarmed by Karl Menzel Senior BiologistIT WAS JUST another creek to cross as far as the frisky yearling white-tailed buck was concerned. He hesitated momentarily on the edge of the concrete side, then entered the Ainsworth Irrigation Canal. It turned out to be his longest swim and his last.

He swam to the other side of the canal and attempted to leave. But this "creek" had slick sides, kach time that he tried to climb out his hooves slipped under him. He struggled repeatedly until they were worn raw The current kept pushing him downstream and soon, his energy exhausted, he drifted into a trash rack and drowned.

Merritt Reservoir and the Ainsworth Canal were constructed by the US. Bureau of Reclamation to provide irrigation for the vicinity of Ainsworth in north-central Nebraska. Merritt was completed in 1964 and at capacity has an area of 2,906 surface acres. The canal commences at the dam, 27 miles southwest of Valentine, and extends eastward for 52.8 miles to U.S. Highway 20, east of Johnstown. This man-made waterway along with 174 miles of laterals and 63 miles of drains, irrigates about 34,000 acres of farmland.

The Ainsworth Canal is lined with concrete along its entire length. In the western section of 22 miles 38 NEBRASKAland the height is 8.4 feet, bottom width is 9 feet, and water depth is 7.22 feet at capacity. In the eastern section of 30.8 miles, the height is 6.5 feet, bottom width, 7 feet, and water depth, 5.3 feet at capacity. Water velocity is 6.22 feet per second in the lower section and 3.4 feet per second in the upper section. Maximum discharge is about 580 cubic feet per second. The canal was completed in early 1965.

Along the canal are 17 bridges, 16 drop structures, and 6 siphons. Five of the siphons are located at creeks and the sixth at U.S. Highway 20. These huge tubes are real death traps for deer since the animals haven't got a prayer of escape once they fall or are carried into one. Drop structures are not insurmountable barriers when the flow is down but when the canal is running full head they probably would stop the animals from moving through.

The canal is a serious hazard to deer yet technicians have used the bad situation to further their knowledge of deer behavior and movements. During the peak periods of deer movement, two men make daily checks along the canal and try to rescue as many of the trapped animals as they can. In 1965, Nebraska Game Commission personnel patrolled the canal every day from May 27th to June 28th. This year, the patrol began on May 26th and continued until August 1st.

Ropes and tranquilizer guns are the rescue tools. If a deer can be pushed to the lower end of a drop structure or to deep water, roping is the preferred method. It's a pulling and heaving job all the way after that but it saves the deer. The men have to avoid the flailing hooves of the panicky animal and at the same time try to keep him from injuring himself. It is not an easy job but after a few close squeaks, the men perfect a technique that gets the job done. In shallow water, where the deer has more freedom of movement, the tranquilizer gun reaches out to subdue the trapped animal for removal from the canal. After the tranquilizing chemical wears off, the deer recovers and goes his way.

All deer are ear-marked with metal tags while colored nylon streamers are used to identify individuals. Tag numbers and conditions of the rescued animals are recorded. Post-release observations of the tagged deer are also recorded.

Although Game Commission personnel do the very best they can to rescue the deer, some of them still drown or are so badly injured that they must be destroyed. Leg injuries are the most common as the trapped animals keep trying to scale the sides of the "cement" creek. If the technicians decide an animal is too badly injured to recover, they dispatch him on the spot to prevent further suffering.

Real trouble for the deer started on June 1, 1965,

when the canal began carrying water. It didn't abate

until October 10th when the flow was curtailed. During

that period, 136 deer were observed or reported to

Game Commission personnel. Of these, 75 were rescued, tagged, and released, 34 eluded capture, 16 were

dead, and 7 died in handling. Four deer wore tags from

NOVEMBER, 1966

39

a previous study project. Game Commission personnel

are confident that more deer were trapped in the canal

and that both live and dead animals were removed by

individuals who failed to report their rescue and recovery efforts to the Commission. All in all, the Game

Commission believes that at least 200 deer were

"caught" in the canal in 1965. From May 2 to August 1,

1966, 98 deer were reported in the canal.

a previous study project. Game Commission personnel

are confident that more deer were trapped in the canal

and that both live and dead animals were removed by

individuals who failed to report their rescue and recovery efforts to the Commission. All in all, the Game

Commission believes that at least 200 deer were

"caught" in the canal in 1965. From May 2 to August 1,

1966, 98 deer were reported in the canal.

Daily patrols saved 33 of the victims while 42 were either drowned or so badly injured they had to be destroyed. Eight of the deer wore tags proving that deer do not always profit from past mistakes. Six were dead indicating that their luck ran out on their second go round with the deadly canal.

Technicians have learned quite a bit from the deer caught in this 52.8-mile stretch of waterway. Of the 120 deer positively identified in 1965, 70 were whitetails, the others mule deer. In 1965, 63 whitetails were identified out of a total of 86 animals.

The canal flows through terrain that harbors both species and since neither seem to have any marked ability to avoid the canal, technicians believe the whitetails are more active and thus more accident prone than the more stolid mule deer. Whitetails may not be too smart when it comes to avoiding the canal but their ability to give hunters the slip is not impaired. In 1965, the season kill in the area was predominately mule deer with whitetails accounting for only slightly more than 27 per cent of the total take.

Yearlings are the principal victims of the long canal. The peak incidence of sighting and rescue occurs during June and coincides with the fawning period when the yearlings seek new homes.

Streamers have added to the knowledge of deer movements. Movements on 10 mule deer bucks ranged from 4 to 48 miles with the average journey working out at 20.4 miles. One yearling buck apparently decided that the canal country wasn't healthy for him. He hightailed 48 miles within 17 days after his rescue. A white-tailed buck fawn was a close second. This youngster put 19 miles between him and the tagging 40 NEBRASKAland site in 35 days. Overall distance champ was a mule deer doe. She traveled 37 miles in 93 days and then added an additional 15 miles within 209 days from date of tagging. Thirteen of the tagged deer were shot during the 1965 season. Despite their restlessness, the whitetails as a group did not travel as far as their cousins. Five bucks were checked out and found to have averaged 16.4 miles, four miles less than the distance traveled by a comparable group of mule deer.

It's a cinch that the Ainsworth Canal will continue to trap and kill deer but solutions to the problem are being studied. The two best methods would be to cover the canal or to install deer-proof fencing along its entire stretch. Crossings could be installed at intervals to let the animals go their way. However, both of these solutions are costly.

An experimental device now in the testing stage shows promise and may be instrumental in reducing the annual toll. A-frame deflectors and wooden cleats were installed adjacent to two of the deadly siphons in 1966. At least one white-tailed doe used the devices to escape a watery grave but one rescue is not a true indicator of what the A-frames can or cannot do.

To get a truer picture of the A-frames' potential, technicians released four semi-tame deer in the canal for a more comprehensive test. All the deer except one used the new device to get out of the big "ditch". The one failure was due to a spreading of the bars on the A-frame which allowed the deer to pass through it. Technicians believe that six-inch spacing is about optimum for the A-frames. More tests will be made and if they prove out with wild deer, recommendations for more of the unique installations will be made.

Until that time or until some ingenious chap comes up with a better solution, the Ainsworth Canal will continue to exact its deadly toll. Technicians anticipate that 150 to 200 deer will be trapped each year.

Loss of some of these fine game animals is not pleasant to contemplate and the Nebraska Game Commission is working hard to eliminate it, but until the final solution is reached more deer must die. But with each victim, technicians are getting a little closer to a remedy and someday in the not-too-distant future, a workable and efficient device to save deer from the canal will be found. In the meantime, ropes and tranquilizer guns will continue to save many of the trapped animals.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1966 41

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA...

Beaver