SPEAK UP

NEBRASKAland invites all readers , to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome.—Editor.

THIRTY YEARS A READER - "A man picked up my May issue of NEBRASKAland, and said, "How long have you been reading this magazine?"

"I said for 30 years. I could be wrong, but we used to get it free years ago, and it was called Outdoor Nebraska. This was back in the 30's, when I was a postmaster. The carriers counted pheasants (they still do) and we in the office got it free. The last four years since I retired, I got it about every other year. This year it was a Christmas present. How far did I miss when I said I had been reading it over 30 years?" - Donald Flang, Grand Island.

Outdoor Nebraska was first published in 1926 as the official bulletin of the Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Game and Fish, under the direction of Frank B. O'ConnelL — Editor.

STRONGER STAPLE-"My husband and I enjoy Outdoor NEBRASKAland very much. The photography and color are excellent. We desire to keep the magazine in our permanent library.

"There is just one main thing wrong. They are not stapled together very securely. On the first look-through, often the center comes loose. This has happened to more than half the copies I have received."-Mrs. George J. Myers, Gibbon.

Steps are being taken to correct this. — Editor

KID'S ZOO-The July issue of Outdoor NEBRASKAland came to our home and the picture of Brenda Traeder in front of the Iron Horse Railroad engine at the Children's Zoo is exceptionally good. I only wish the people could know how much work went into the taking of the picture of the summer-clad young lady on a mighty cold and windy March day. "And, the picture of the two girls and the totem pole on Page 42 is an inspired, unusual, and colorful shot. I know that the Lincoln High School boys and their teacher, Jim Joyner, who worked together for two years on the totem, will be very much pleased.

"You had another photographer at the Children's Zoo more recently, taking shots. We'll look forward to seeing them and the story for which Bob Snow has been collecting material.

"Attendance at the Children's Zoo keeps snowballing. Many days, more than half of the cars in the parking lots are from outside Lincoln. One Sunday, we had more than 2,300 people in the zoo, and 1,700 rode the Iron Horse Railroad. A check in the afternoon showed cars from 23 counties and 11 states."- Arnott R. Folsom, President, Children's Zoo Association, Lincoln.

RINGNECKS-"R. B. Hartby of Otis and Dr. Cone were 13 years stocking the first pheasants in Nebraska. My brother, V. C. Rasmussen, Tom Ley, and Sofus Olson, three businessmen from Rockville, Nebraska, shipped in two cocks and four hens in 1907 and turned them loose in the hills just outside of town.

"By 1917, Howard and Sherman Counties were loaded with pheasants. Bill Lemberg of Boelus was hired by the state to net these birds for restocking. He caught hundreds of them each winter." -H. C. Rasmussen (age 79), Bloomfield.

SIMMONS —"I was most gratified to read your article in the March issue entitled, 'Pioneer with a Brush'.

"I am one of the privileged few who own one of Charles Simmons' original oils.

"I think it would be quite wonderful if some more of these could be reproduced in the future. The double-page reproduction will occupy a permanent position of display in my home."-Charles F. Harrison, Torrance, California.

THE COVER: Wood duck clan out for a swim turns placid Nebraska pond into kaleidoscope of coldr photo by Lou Ell

This Poison Business

WELL BEFORE the appearance of SILENT SPRING, the potential dangers of unregulated use of pesticides were looming large to Nebraska Game Commission researchers. Studies were begun in 1963 to learn whether the chemicals being used were finding their way into Nebraska's wildlife. With co-operation from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, tissues of pheasants and channel catfish from typical farming areas were analyzed. Pheasants and their eggs were found to contain sizeable quantities of several persistent insecticides. The catfish and other species of fish tested contained similar residues.

To get information representative of the entire state, more extensive studies were initiated, based on samples taken systematically throughout the state. To learn the kinds and amounts of pesticides actually used, operators of 724,000 acres were personally interviewed. These lands represented diverse types from Pine Ridge timberlands and Sand Hills rangeland to irrigated farmland and mixed dry land agriculture. This study is confirming that through the five-year period being tabulated from 1960 through 1964, Nebraskans applied hundreds of tons of pesticides including aldrin, heptachlor, dieldrin, D.D.T. and B.H.C.

Researchers are presently analyzing catfish from every major watershed in the state for these chemicals to relate their levels to the rate of application, the time lapsed since application and the character of the soils where they were used.

As work progresses, the importance of long-range studies become more and more evident. Through the years being studied the use of chlorinated hydrocarbons dropped markedly in Nebraska. However, the wildlife has not experienced a comparable reduction in exposure; some of the very stable chemicals applied years ago still remain in the environment, unchanged.

Nebraska's studies are proving to be of vital importance in understanding the losses of wildlife investigated each year. However, they can supply only a small part of the knowledge so urgently needed in this field. It is heartening to learn that others are also concerned with the long-range affects of these deadly chemicals as evidenced by Mr. Swift's article which is reprinted here.—-Editor

WHEN RACHEL Carson's book, SILENT SPRING, was published it immediately became a bible to a great many people. To others it was a document of error and even falsehood. The more it was vilified or praised, the more it was read. The result was a chain explosion of charges, counter-charges, a threatened lawsuit, a frantic increase in research by public agencies and universities, a rash of proposed laws, and endless editorial comments.

Whatever else can be said, it brought the now-widespread use of chemical poisons into the open for legislative and household debate. Chemical poisons immediately became a public issue with almost violent overtones.

Prior to the release of SILENT SPRING the public had long been propagandized by scientists in the employ of the chemical industries, certain Federal bureaus and the agricultural interests, that pesticides —economic poisons -were, in great measure, the future salvation of humanity. Even Moses never preached with greater authority.

On the other hand, research as to the short and long-term effects of these poisons on animal and vegetable life had never been centralized, nor properly financed, and was often of a timid sort due to economic pressures.

But with the startling impact of SILENT SPRING, there were immediately agonized cries of foul play, and all the power of corporate money, all the power of vested agricultural interests, public and private, were brought to bear on squelching this heresy. In one state a health commissioner even sought to ban this dreadful book from the public libraries.

Not only were Miss Carson's findings attacked, but so were her qualifications as a scientist, her integrity, and her motives. The pattern of attack was analogous to the time-worn strategy of a court case. If the facts cannot be disproved, then attack the witness. This type of offensive was soon enlarged by statements to the effect that scientists who drafted definitive guidelines in" a Federal report, USE OF PESTICIDES, were incompetent except for one member.

All the overpowering vehemence, bluster, and self-righteous scorn unleashed to suppress free thought and discussion on this issue makes the Spanish Inquisition and the burning of witches more understandable. Although these latter two chapters of human history had to do with religious dogma, their purpose was to stifle self-analysis, free debate, and free questioning through the fear of physical torture. In both 6 NEBRASKAland instances the self-appointed monitors of human behavior burned books along with human flesh. This 20th-century attempt to suppress free intercourse of discussion and facts was through economic pressures and loss of jobs, but the fact remains that this type of human bondage can prove more dangerous than the pesticides.

The reactions to this ground-swell of protest by the manufacturers and users of poisons has developed some interesting aspects of inquiry.

What are the basic reasons for their reactions?

With so little prior research regarding ultimate, long-range effects, how can it be so flatly stated that the use of poisons is purely altruistic and humanitarian? The basic reason for an industrial and agricultural partnership is the profit motive. Nothing else. All other considerations including any moral duty to feed the world are secondary.

Chemical industries have found poison-making a highly lucrative business, and through its use farmers increase their profits —at least for the time being—by killing pests and reducing cultivation costs. From the standpoint of the farmer, to reduce labor costs and guarantee a higher crop yield is an understandable ambition. However, the agricultural leadership emanating from the agricultural schools has encouraged a one-crop type of farming which is conducive to pests and creates an ideal environment for them. Agricultural schools have a tendency to indulge in the jehovah complex, and it must be remembered that at one time they advocated up-and-down-hill plowing and cultivation as well as farming sub-marginal lands which were finally abandoned to tree planting. In the long haul, it may again be found that their feet are made of clay if they continue their loose and widespread use of poisons.

The profit motive as a single-purpose priority is not confined only to the use of poisons but it is apparent in the destructive forces of pollution, commercialized recreation, erosion because of bad farming methods and highway construction, neglect of small timber holdings where no fast return is apparent. One of the most sinister of destructive forces is strip mining.

There is no intention of placing the profit motive in a bad light, but today corporate and individual responsibility goes with the use and management of all the nation's resources. The huckster's attitude of the market place of "let the public beware" can no longer prevail. It is because of this flaunting of responsibility that so many laws are passed governing resources.

As populations increase there becomes a national equity in all resources regard- less of ownership. This may not be an altogether palatable premise, but it is a fact. And to dismiss all potential damage through the use of poisons as the "price of progress" is a shallow and untenable argument.

SILENT SPRING has given encouragement to many of the middle register who want some long-term and fundamental investigations into the use of poisons, and they are not particularly interested in teaming up with the extremists of either camp. The public has a right to demand impartiality from its government bureaus and schools of higher learning. Tax-supported institutions should not have a ring in their noses and be led by powerful lobbies. Industry and agriculture can no longer win friends by yowling like scalded cats, nor should ridicule, scorn, or emotions from any group be a substitute for facts.

Facts have and are piling up from the standpoint of poison residues in many forms of wildlife all over the globe, in enormous fish kills, general pollution, and in lawsuits where humans, animals, and crops have been affected or killed. In states where wildlife agencies have some authority — usually not enough — restrictions are being placed on the irresponsible broadcasting of poisons, and the types and kinds which can be used; but effective federal laws are still a long way off. There are too many federal and state employees forgetting that they work for the (Continued on page 49)

An afternoon putting on the grassy green is a hole-in-one idea for fun in October, as shown by Miss Lynda Orr, Outdoor NEBRASKAland's hostess of the month. Miss Orr is a senior at Nebraska Wesleyan University, majoring in medical technology. Chosen as Wesley an's 1966 Beauty Queen, she also scores high academically and is a member of Beta Beta Beta, a biology honorary; and Cardinal Key. She spent last summer in Finland living with a Finnish family, under sponsorship of the American Student Information. Service. Miss Orr is the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Roger A. Orr of Fremont.

October Roundup

You don't have to be a hunter to bag a share of month's fun and gomes, but it sure helpsNEBRASKA'S MAP of October events looks like a jack rabbit's path—it's a hop and a skip back and forth across the state for a zany month of fun. Starting our route on the mighty Missouri River and cutting a caper to the west, it's no surprise to find that the lusty river town of Brownville is leading off with a rollicking fall festival on October 9th to celebrate the days when steamers docked at her banks and poured out rough and ready adventurers onto the open prairies. Today's loose-foot won't get out of town without a day of fun.

Up river, at Plattsmouth, the State Game Refuge is primping its feathers for a visit by the Omaha Bird Club on October 29th.

Omaha, the gateway to the Golden West, offers a list of events that is longer than a youngster's note to Santa. The Civic Auditorium lays out its mats for five professional wrestling bouts on October 1, 8, 15, 22, and 29th. But it's even tougher to beat the Joslyn Art Museum calendar. Joslyn plans a Tuesday Musical in Concert Hall on October 2. Roten Prints from the Roten Gallery in New York will be on display from October 15 through November 6. Coming from London is the Nelos Ensemble to present chamber music on October 30.

The Omaha Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Joseph Levine, celebrates its twenty-ninth season with a new seven-concert program. Five internationally famous guest artists are scheduled, beginning with a double performance, October 10 and 11, by Jennie Tourel. The world famous mezzo soprano will perform works by Vivaldi, Mendelssohn, Ravel, and Poulenc.

Creighton University welcomes its alumni back to campus for a week of festivities beginning October 2 with an Alumnae Style Show. A Founders' Day Dinner, October 6, honors the laying of the university's cornerstone in 1878. A series of seminars and a dinner are planned for medical school alumni on October 29th, who will be on hand for the dedication of a $3 million medical school building.

Omaha University celebrates its Founders' Day, October 8. Its first college term was held in 1909.

Ak-Sar-Ben will swing, October 22, when Guy Lombardo provides the beat for the grand ball culminating in the coronation of the Ak-Sar-Ben queen and king.

Omaha's rich list of activities takes on a new jingle, October 22 and 23, when the Omaha Coin Club holds an exhibition at the Sheraton-Fontenelle. Collectors from the midwest compete in five categories — ancient coins, U.S. coins, foreign coins before 1500 A.D., foreign coins after 1500 A.D., and miscellaneous and specialized coins.

A hunter's breakfast at Laurel, October 23, shoots off the second day of the season on ringnecks. It's anyone's guess what's on the menu for lunch but the odds are two to one for pheasant. The 2,325 permit holders will be hot after wild turkeys on October 29, when the season opens for nine days. Pheasants are legal prey one-half hour before sunrise to sunset while wild turkeys have to dodge the hunters from one-half hour before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset. Sunup, sundown tables will be published in many newspapers.

Heading to Dodge, October 31, are wee ghosts and goblins to haunt the streets during the Kiddies Halloween Parade.

In Lincoln this month zooms off with a Governor's Youth Safety Conference at the Nebraska Center, October 1. The meeting is for high school juniors and their instructors and is sponsored by the Nebraska Safety Council to instruct young people on how to organize and conduct safety programs in their own high schools with special emphasis on traffic safety.

Another high-flying month of excitement awaits football fans when the University of Nebraska Huskers and the Nebraska Wesleyan University Plainsmen swing into action. Top of the heap are homecoming games at each school. The University of Nebraska invites its alumni to watch October 15 when Big Red clashes with Kansas State. Wesleyan University Plainsmen head onto the field October 28 for a run-in with William Jewell College of Liberty, Missouri.

The Nebraska Industrial Trades Show on October 1 and 2 highlights the Pershing Auditorium schedule. The 1966-67 Community Concerts program opens October 13 with the melodious tunes of Richard Rogers.

The Sheldon Art Gallery features mosaics by Jeanne Reynal, October 2 through 30. A Library of Congress Loan Show, The Art of Print Making opens October 11 along with the Howard S. Wilson Memorial Collection.

The Salt Creek Wrangler's Saddle Club was organized in the spring of 1946 and has had a galloping go-round of events ever since. The last show of this season is October 9th at the Rodeo Grounds, one mile south of Pioneers Park.

Art Buchwald, identified by Time Magazine as the most successful humor columnist in the United States, will be at the Nebraska Union ballroom of the University of Nebraska, October 20. Buchwald is a best selling author and is syndicated in 225 papers around the world.

Grand Island and Hastings plan tuneful activities this month. High school bands from all over Nebraska are invited to strut in a grand parade and to compete in street marching during Grand Island's Harvest of Harmony, October 8th.

The Hastings Chamber of Commerce and Hastings College are together presenting $600 in musical scholarships to high school seniors as part of the Hastings Melody Roundup on October 15th. School bands will parade and be treated to a luncheon at Hastings College.

The Prairie Schooners Square Dance Club of Sidney is keeping things stomping in the western end of the state, October 29 and 30, when the club will hold its second annual Square Dance Festival.

From east to west, from north to south, there's plenty of opportunity in Nebraska to cut up with a fine time during October.

THE END OCTOBER, 1966 9

WHAT TO DO

October 1 — Kearney — Homecoming, Kearney vs. Peru State, Football 1 — Omaha — Pro-Wrestling, Civic Auditorium 1 — Lincoln — Governor's Youth Safety Conference, Nebraska Center 1 — Lincoln — Wesleyan University vs. Dana College, Football 1 — Doniphan — Fall Festival 1-2 —Lincoln —Nebraska Industrial Trades Show, Pershing Municipal Auditorium 2 — Omaha — Tuesday Musical, Joslyn Art Museum 2 — Omaha — Alumnae Style Show, Creighton University 2-30 — Lincoln — Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal on Exhibition, Sheldon Art Gallery 3-22 — Omaha — Art Across America on Exhibition, Joslyn Museum 4 — Omaha — Student Convocation, Creighton University 5 —Lincoln —"Eroica", Nebraska Theatre 5 —Lincoln —Pro-Wrestling, Pershing Auditorium 6 — Omaha — Founders' Day, Creighton University 6 — Lincoln — Grand Ole Opry, Pershing Auditorium 7 —Lincoln —Wesleyan University vs. Colorado College, Football 7-9 — Lincoln — English Teachers Seminar, Nebraska Center 8 — Lincoln — Firemen's Annual Dance, Pershing Auditorium 8 — Omaha — Greater Creighton Convocation, Creighton University 8-Omaha-Pro-Wrestling, Civic Auditorium 8 — Omaha — Founders' Day, Omaha University 8 — Taylor — Alumni Banquet 8 - Grand Island - Harvest of Harmony 8-11-North Platte - Grassland Livestock Association Show and Sale 8 — Kearney - Kearney vs. Wayne, Football 9 - Seward - Organ Recital by G. Knopf, Weller Auditorium 9 - Brownville - Fall Festival 9 — Lincoln — Salt Creek Wranglers Horse Show, Rodeo Grounds 10-Lincoln-"Half A Sixpence", Stuart Theatre 10-11 —Omaha —Jennie Tourel in Concert, Joslyn Museum 11-23 —Art of Print Marking on Exhibition, Sheldon Gallery 11-Nov. 13 —Lincoln —Howard S. Wilson Memorial Collection on Exhibition, Sheldon Gallery 12 —Columbus Day 13 —Lincoln —Richard Rogers in Concert, Pershing Auditorium 14 —Lincoln —Wesleyan University vs. Doane College, Football 15 —Omaha —Pro-Wrestling, Civic Auditorium 15 —Lincoln —Homecoming, University of Nebraska vs. Kansas State, Football 15 —Hastings —Melody Roundup 15 —Diller —Harvest Holiday 15 —Seward —Concordia Homecoming vs. Westmar, . Football 15-Nov. 6 — Omaha — Roten Prints and Collector's Choice on Exhibition, Joslyn Museum 16 —Seward —Lyceum Program with the Rev. W. Bielingberg, Concordia College 18 —Harrison —Annual Extension Meeting and Fun Feed . , 19 — Lincoln — Pr\>-Wrestling, Pershing Auditorium 19 - Lincoln-,fHallelujah The Hills", Nebraska Theatre 19 —Taylor —School Boosters Smorgasbord 20 — Lincoln — Art Buchwald Speaks, Student Union 20 — Seward — Convocation with Colen Jackson, Concordia College 20-21 —Lincoln —Forum on China, Wesleyan University 21 —Omaha —Dick Walter Travelogue, Joslyn Museum 21-22 — Omaha — Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation and Ball 22 — Chadron — Chadron State vs. Kearney State, Football 22 —State-wide —Pheasant Season Opening 22 —Omaha —Pro-Wrestling, Civic Auditorium 22-23 — Lincoln — Nebraska Custom Auto Show, Pershing Auditorium 22-23-Omaha-Omaha Coin Club Exhibition, Sheraton-Fontenelle 23 — Laurel — Hunter's Breakfast 24 — Fairbury — Farmer-Retailer Banquet 25 — Lincoln — Lincoln Symphony Concert, Stuart Theatre 26 — Seward — Lyceum Program with A. Chiu, Concordia College 27-28 —Lincoln —District 1 Teachers Convention, Pershing Auditorium 28 — Lincoln — Homecoming, Wesleyan University vs. William Jewell, Football 29-Plattsmouth-Omaha Bird Club Outing to Plattsmouth State Game Refuge 29 — Lincoln — State High School Marching Band Festival 29 — Lincoln — University of Nebraska vs. Missouri, Football 29 — Omaha — Pro-Wrestling, Civic Auditorium 29 — Omaha — Reunion of Medical School Alumni, Creighton University 29 — Hastings — Hastings College vs. Kearney State, Football 29-30 —Sidney —Second Annual Square Dance Festival 29-Nov. 6 —Special Areas —Wild Turkey Season Opening 30 — Lincoln — Reformation Festival Sunday, Pershing Auditorium 30 — Omaha — Chamber Music, Joslyn Museum 30 — Omaha — Dedication of $3, million Medical School Building, Creighton University 31 —Lincoln —Extra Point Football Club Luncheon, Pershing Auditorium 31 —Dodge —Kiddies Halloween Costume Parade 31 - Lincoln - "Tidewater Trails", Audubon Wildlife Film, Love Memorial Auditorium October-October 23 - Lincoln - New Names in Latin American Art on Exhibit, Elder Art GalleryCHECK POINT GAME

GAME CHECK stations are different things to different people. To the biologist they are tools of information. To the hunters they are both a disgusting nuisance, and a pleasant excuse for displaying that extra-special trophy. Depending upon your point of view, check stations are both good and bad.

Nebraska, like many other states, requires certain species of game to be checked at designated stations. Successful deer hunters in Nebraska have been required to check their bagged animal through an Hunter and biologist both benefit from dope gleaned during roadside review official check point since 1945 when the lirst season in recent times was held. Since that time, in excess of 103,000 deer have been checked. In addition, 8,000-plus antelope and better than 3,000 wild turkeys have been officially sealed at game check stations. This has permitted Nebraska to maintain complete detailed records on its big-game harvest. Also, along with the big-game check stations, which are mandatory, voluntary stations for pheasants, quail, ducks, and grouse are maintained.

Information from check stations can be of direct benefit to the hunters. Based on the analysis of data from previous years, it has been possible to extend the length of the season for certain species and to modify other regulations to favor the hunter. For example, deer hunters will recall that the season length a few years ago was five days. Upon examination of check-station data it was shown that an extension in the season length to nine days would result in about a 20 per cent increase in hunting success and still keep the harvest within safe limits. Based on this knowledge, the season was extended and the predicted increased hunter success resulted.

A few years ago, the area open for grouse hunting was quite restricted until surveys were conducted in both the open and closed areas. This data coupled with broad studies, breeding-ground surveys, and supplemented with the check-station information resulted in an expansion of the grouse-hunting area. This liberalization has permitted better utilization of the resource and allows many sportsmen to hunt closer to home. With other species, where an increase in season length or expansion of open area would jeopardize the resource, no changes have been recommended. Thus, information from check stations aids in the development or modification of regulations.

One important advantage of check stations is providing complete kill information shortly after the season is completed. The only other method of getting harvest data is through a questionnaire survey. This can be a mandatory return, in which part of the license serves as a record or a voluntary questionnaire.

With the mandatory return the license stub is removed from the rest of the license and the proper harvest information is recorded and returned to the game department. In either case the game department is dependent upon the reporting accuracy of the individual hunter. Usually this type of survey will not provide complete harvest information since some of the cards are never returned. Also, the information is not available until several weeks after the season. Several reporting biasis are built into a questionnaire survey. One which became apparent from a questionnaire sent to turkey hunters is that the hunter who bags his game has a greater tendency to report than the one who is unsuccessful.

To the technican, results obtained from game check stations can tell a detailed story not only about the animals that are brought through the stations, but also about those that remain in the field. Age information from deer and antelope let the biologists know how close to the proper harvest level the herd is being cropped. Age ratios also tell something about the productivity in the different management units. In those units in which production is high and herds are building rapidly, a greater harvest can be extracted than in units where herds are showing a less rapid increase. Check stations have permitted a closer harvest then would have otherwise been possible.

The old adage of "a bird in the hand being worth two in the bush" is true when it comes to evaluating annual production. Age-ratio information in general, provides the answer as to how successful the various game species were in producing young. It is a way of looking back at the production period. Once the technican has the chance to actually handle the game and to review check-station results, he will have a much better idea of the reliability of some of the other data that has been collected during the year.

Information about the health of various wildlife species can also be obtained from check stations. During some of the past seasons, blood samples have been taken and checked at the Bureau of Animal Industry and Agriculture Research Laboratory. Information derived from these checks has been important for showing that most wildlife species are relatively free of disease, especially those diseases common to domestic livestock.

Additional information which comes to light from examining hunter-killed game, is the sex ratio, species composition, condition of the animal, and distribution of the kill. All of these factors are important for evaluating the impact of a season and for making intelligent management decisions. For the hunter, bringing his bagged game to a check station or stopping at a roadside check point requires only a few minutes of time — not a bad exchange when the advantages of maintaining check stations are examined.

Many of the hunters who stop to have their game checked believe that the main reason for check stations is for law enforcement. As a result, there is usually greater care exercised to comply with the law when a check station is set up. This can be of direct benefit to management. However, the principal reason for the station is to collect information on the game.

Nebraska's game-management program has made considerable strides in providing recreational opportunity for the sportsman over the past several years. Part of the reason can be attributed to the information that has been obtained through check stations. Minutes of your time can mean many days of added hunting pleasure.

THE END OCTOBER, 1966 11

Stranger to Sharptails

Carl Faulhaber and kin do honors when a visitor seeks on introduction to grouse. Hunt is also a lesson in coverGROUSE FLEW up from the shoulder of the highway and floated with cupped wings over a choppy. I braked the car and rubbernecked until the bird vanished. Suddenly, the opportunity to hoof it over the autumn-browned Sand Hills south of Valentine, Nebraska for sharp-tailed grouse was just too inviting to pass up. That bird was the clincher. Right then, I resolved to go grouse hunting, something I had never done before.

I wheeled into Carl Faulhaber's hereford

ranch to ask permission, and before I knew

it, I was seated in the ranch house living

room. Seventy-one-year-old Carl Faulhaber

stretched and grinned at brother-in-law Leo

McGuire and Leo's son, Don.

it, I was seated in the ranch house living

room. Seventy-one-year-old Carl Faulhaber

stretched and grinned at brother-in-law Leo

McGuire and Leo's son, Don.

"He's never tried our grouse. What do you say we take the afternoon off so all of us can give it a go? The ranch will keep," Carl suggested.

"A grouse isn't a hard bird to hit, once you get close enough to him," Leo interjected, "but be ready to do a lot of walking. Sometimes they're in the hay meadows, other times in the shelterbelts. Often, you have to go back into the hills to get them."

"Time was," Carl added, "when I could hunt them from a wagon. That was back in the days of market hunting, and there was quite a demand for sharptails and prairie chickens. I field dressed the birds right away, then stuffed them with grass to keep them fresh during shipping."

Don rose impatiently. "We better get going. It's a still day, so we'll probably have to do a lot of walking before we find a bird who doesn't hear us coming a mile away."

The four of us trooped out to a waiting pickup. Carl, Leo, and I crowded into the cab while Don mounted up behind. Carl and Don packed 12-gauge pumps, Leo had a 12-gauge auto, and I carried a 20-gauge Magnum. All of our shells were loaded with No. 6's. Carl drove (Continued on page 49)

Sand Hillers explain markings of a sharptail. Chickens are rarity here

The Kinkaiders

by Warren Spencer Mosf historians downplay Nebraska's own little war. But bullet in back was real for Sand Hills settlersWHEN MOSES P. Kinkaid pushed his namesake act through congress in 1904, that started something that Nebraskans will never forget. His Kinkaid Act went into effect on June 28,1904, and war was declared between cattleman and settler. It was just a small war, but it was Nebraska's own war, with only occasional barrages rolling in from Washington.

According to Kinkaid's pet project, public land in the Sand Hills, except that which could be irrigated, was open to settlement. This was really nothing new because for some years, 160-acre tracts had been available. But those who settled these small parcels were soon burned out from lack of water and plenty of sun. The congressman from Nebraska's "Big Sixth" district originally authored his proposal to offer settlers 1,280 acres. Congress took one look at the measure, divided by two, and passed the bill with the stipulation that $800 worth of improvements be made on the section within five years, the final ownership date. The law hit the public like gold-rush fever.

Towns like Broken Bow, North Platte, and Alliance suddenly exploded into cities as land-seekers flooded the hills. Saloons and boarding houses sprang up where a few hours before there had been only dry prairie. With hotels and homes filled to capacity, tents and wagons became common sights around the edges of the towns. Yet this was only the advance guard for the Kinkaiders. Most were men who moved into the country to stake their claims, then return with their families later. But there were widows who had no family in the procession to the land offices, too. For them, this was the start of a new life and a chance to drown past experiences in the work of establishing new homes. They, along with other candidates for government land, stood in line for days to await the filing offices' openings. Many camped in front of the offices over night to assure their places in line. At the Alliance office the line had grown to nearly 400 by the time filing began. Even at their best, the officials were able to process only half the applicants that day. The rest were given numbers to hold their places in line for the next day. The General Land Office has no definite records of the number of claimants processed under the Kinkaid Act. But almost 1,600 patents were granted for about 800,000 acres before November 1910.

The act knew no racial boundaries. A colony of Negroes moved into the Sand Hills, settling near Brownlee in southeast Cherry County. For several years the Negroes managed to make a living on their land, but after several (Continued on page 52)

OCTOBER, 1966 17

Long-Handled Fishing

By Charles DavidsonROGER AND MARK Fattig were having a splashing good time in the south branch of the Platte River. The two competitively-minded brothers were spearing carp in the crystal-clear waters and getting themselves drenched in the process. Neither boy objected to the wettings for it was July and the Nebraska sun was living up to its reputation.

Mark was the first to see a carp. Seconds after he and Roger waded into the shallows, the younger Fattig spotted a black shadow cleaving through the knee-deep water. Both boys took after the escaping fish but he reversed his field and headed downstream. Roger, moving quickly, was able to counter the carp's break. Older and faster than his brother, he wheeled and splashed down current, hoping to overtake the frightened fish. He was close when the carp changed tactics and darted for cover under an overhanging willow.

Mark was trying to keep pace with his brother but he lost ground in the downstream dash. He stopped about five yards from his brother and started eyeing the undercut bank, trying to spot the hidden fish.

"There he is. He's coming your way", Mark yelped as the fish broke out and headed into the main channel.

Roger aimed at the flashing carp and jabbed hard in a near miss that turned the fish back toward Mark.

"I missed. Get him", he warned. "He's just to your left."

Mark lunged but the carp eluded the deadly tines and turned back toward Roger. This time, the boy was ready. His spear went almost straight down to nail the carp in the back. Triumphantly, the youngster lifted his spear with its two-pound burden and held it up to show Mark before tossing the take onto a sandbar.

Carp spearing was a new experience for Roger and Mark although both had tried bow and arrow fishing for them. Sons of Dale Fattig of Brady, Nebraska, the two boys were ardent rivals in about everything. Fishing and hunting are their favorite sports and when their father suggested that he would like to try some smoked or pickled carp, the two boys were more than willing to rustle up the main ingredient.

They rigged up two five-tined spears on 12-foot bamboo handles and started out. The tines on their fish-getters were five inches long and eash was tipped with a Vi-inch barb. Spearing non-game fish is legal in Nebraska from April 1 to December 1, but only during the daylight hours from sunup to sunset.

Roger and Mark hadn't picked the best of times for spearing which comes in the spring when the carp are spawning in the shallows, but even so they were finding plenty of action in the holes and along the banks of the summer-shallowed river.

After the boys calmed down from the excitement of their first catch, they waded upstream at a good clip watching for more fish. Both saw the V-wake of an escaping carp at the same time and dashed after him but the carp had a 15-yard advantage and he wasn't about to lose it. Roger picked a spot where he thought the carp would be and ran toward it with Mark right behind him but the carp wasn't there. Their running had roiled up the water so the boys stopped and waited for it to clear. Roger was plotting strategy. "I'll run ahead, get above the carp and try to turn him down to you," he suggested.

Mark agreed that it was a good idea so he waited as his brother plowed ahead hoping to outflank the fish and spook him into a turn around. After covering a reasonable distance, Roger turned and started working downstream. The plan was good but there was one serious flaw in it.

Roger had stirred up so much sand with his jaunt that he couldn't see below the surface of the water.

"I can't see too well," he complained. "Anything coming your way?"

His brother didn't answer. He was watching a fluff float down from an overhanging cottonwood and was fascinated by its gentle descent to the water. The current caught the fluff and was sweeping it by when a carp rose to the "summer snowflake". Mark was surprised but he made several futile jabs with his spear hoping for a pin.

"Darn it. I keep overshooting," he griped. "What's your secret?"

Spooked by Mark's efforts, the carp seemed unaware of any other danger. He headed straight toward Roger and his waiting spear. One sharp lunge was all it took and Roger had his second prize of the day.

After securing the catch, Roger got around to answering his brother's query. "What we see in the water is somewhat distorted due to refraction. Also these carp are faster than you think," he replied.

Weapons mark the spot where two weary gladiators rest after a day-long siege

Mark switched the subject. "I don't think that last one was the carp we were after. He wasn't big enough".

Roger splashed around, jabbed, and held up a securely-impaled fish. "Is this the one?" he taunted.

"Nope, still not big enough," Mark replied. "By the way, you had better slow down. You're three up on me."

Roger's fish weren't big enough to rate the whopper tag but they did run between two and three pounds.

Mark was growing more determined all the time. There is plenty of rivalry between the two brothers and like all younger brothers he didn't cotton to having his brother top him in everything.

Minutes later, he got his chance. The boys spooked another carp that flashed upstream. Mark churned after him, his short legs throwing up spray like a walrus on the loose.

One thrust was enough as the boy nailed the rough fish square behind the gills. It was a hefty three-pounder and the younger Fattig learned that impaling a fish and recovering him can be two different things. Weight alone can pull big fish off the tines, so experienced spearmen sort of ease their quarry along with an inching shove across the bottom until they can get the fish close enough to land for a pitch out. Luckily, Mark's fish didn't escape on the lift out but he could have.

Two more fish were about all the boys could handle and still run after the carp so they used an extra stringer to stake out their catch in a nearby sandpit.

Equipment for spearing is essentially simple. A spear, a couple of stringers, and a little bug dope are all that are needed. Waders or hip boots are a handicap in this "run after and catch up" method of spearing.

The boys planned to spear for a couple of miles up stream and then retrace their steps. Roger took two more fish before they reached the big hole that marked the half-way point.

"Don't you think we should check it out?" Mark asked.

"It's deep and muddy, but there are probably some carp in there", Roger answered. "You stay here at the inlet and I'll see if I can scare them out. Be ready."

Roger stirred up such a commotion that gunk (Continued on page 51)

FOUR-POINT-NINE

With one citation rock now hanging, Bassett hunter and buddies try for a houseful by Bill HinelRe-creation captures moment when buck gets first hint of danger

TWENTY MINUTES after the deer season opened Dean Hasch found himself looking down the blue barrel of his brush gun at the biggest white-tailed buck he had ever come across. The front sight of the .30/30 did a dance on the buck's forehead to the rhythm of Dean's heartbeat as he waited for the animal to raise his head so he could get a throat shot. Wouldn't that darn buck ever raise his head? Seconds seemed like eternities as the Bassett school teacher waited.

Dean was no novice at deer hunting. He had nailed his first deer at 16 before he graduated from Bassett High School. Ever since he was big enough to tote a BB gun he had hunted. His teachers had been his father, Art, and his brother, Ernie. His training ground had been the 600-acre spread of rolling hills and brushy canyons northeast of Bassett where he was raised. In addition to the family ranch the Haschs farmed several hundred acres of adjoining land and had hunting privileges on some other spreads. Except for his college years at Wayne State Teachers College, Dean had collected venison on the hoof every year.

Now 24, he has taught two years at Ohiowa Public Schools and plans to attend Kearney State Teachers College to work on his masters degree. In between teaching and learning, he never misses an opportunity to get in a little hunting. Deer, pheasants, grouse, rabbits, it seems like there is always something to hunt, not to mention fishing. Right down from where the big whitetail was browsing young Hasch had hooked his first trout.

He had drawn this spot near the top of Oak Creek Canyon the night before at a planning session held at the old home place. Ernie, Dean, and Jim Jones of Bassett had gathered around the dining room table to plan their strategy for the opening day in the Kaya Paha deer management unit. Five other hunting buddies were to join the three early Saturday morning for the hunt but the planning was left up to the Hasch boys and Jim.

The plan called for Gerald Bussinger of Bassett, Ernie, and Frank Shull of Grand NEBRASKAland Island to begin driving at the head end of Oak Creek Canyon. Jim, and Gary Hazard of Bassett were to make their drive down a smaller side canyon. Slim Lewis and his sister, Janice, also of Bassett, were to block the smaller canyon. It was Janice's first deer hunt.

Dawn of opening morning broke cloudless. A cool 65° promised ideal hunting and so far everything was going according to schedule. A few minutes earlier, Dean had driven his car to within a few hundred yards of the canyon after having let the other hunters out along the way. He had stuffed some extra cartridges into his pocket, checked his rifle and hunting knife, and donned his bright red hunting cap. Jeans, a dark sport shirt, boots, and duck hunting coat, along with his bolt-action rifle made his outfit complete.

As he had made his way to the canyon edge a noisy cardinal in a stunted cedar tree sounded off with his "ther-oo, ther-oo, ther-oo, ther-oo", followed by a high-pitched trill. Dean couldn't spot the bird but there was a possibility the cardinal could see something he couldn't so he waited a minute before he went on. Beyond the far end of Oak Creek Canyon, the young hunter heard a car door slam and some noisy chatter. He made a silent wish that the guys down there would knock it off. You have to be quiet if you expect to get within a mile of a stilt-legged whitetail.

Arriving at the canyon rim, Dean sought a good vantage point and finally selected a five-foot cedar tree from where he could scan the opposite slope. He could also see portions of the deer trail which ran along the edge of Oak Creek below, and see north and south up and down the canyon. He sat down with his back to the tree and scanned the oak and cedar-studded slopes.

Sitting with his rifle cradled across his knees, Dean wondered if his companions were moving down the canyon and whether they would spook any deer his way. He kept a sharp lookout towards the north where Ernie was hunting and half expected to see a doe or maybe a buck and several does come tripping down the deer trail below, slipping away from his brother. He wished the birds would clam up so he could hear better.

His musings were interrupted when he felt a sixth-sense awareness of movement down the slope. He hadn't really heard anything and couldn't see anything, but he felt something or somebody was moving down there. Dean stared hard at the underbrush in the half light of the canyon below and then flicked his eyes to the spot of deer trail he could see. Unblinking, he stared until his eyes watered. His every nerve was taut, (Continued on page 51)

Day of the Deer

This big-game animal will be around awhile. Man nearly destroyed, then restored him Photos by Lou El and Gene HornbeckA DEER DOESN'T have too bad a time of it in Nebraska compared to some of the lesser mammals. If he can escape the normal hazards during the first few days of fawnhood, he's well on his way to becoming an adult. Of course, he has to watch out for automobiles, deep irrigation ditches, woven wire fences, and men with rifles but these are normal hazards like crossing the street during rush-hour traffic. Unlike smaller animals, the deer doesn't have to worry about becoming a fast meal for every hungry predator that slithers, flies, pounces, or runs.

Nature was in a benign mood when she designed the deer. She gave him long legs to outrun trouble, an extremely sensitive nose to smell out trouble, big ears to hear it coming, and an inborn ability to sense it before it happens. She made him big enough to be conspicuous and then granted him a hide that blends well with practically any surrounding and just to be on the safe side, nature handed the buck a set of antlers that are no mean weapons when it comes to a showdown. Above all, she gave the deer an adaptability to man and his works.

Nebraska's deer story follows the all-too-familiar

pattern. Before the white men

OCTOBER, 1966

25

The first gypsy-feet who passed through this country on their way to the fur-rich mountains probably knew quite a bit about deer and their scheme of life. They knew that fawns are born in the late spring and that their natal coats are a marvelous blend of brown and white that practically melts into the surrounding landscape. They also knew that a fawn has an instinctive discipline that keeps him motionless when the doe is away. Observation told the early travelers that fawns grow rapidly and usually stay with

their mothers for almost a year before going on their own. Men with their eyes on the beaver pelts of the West and the expectations of rip-roaring good times at the annual fur rendezvous probably didn't consider it earth-shaking information that deer wear red coats in the late summer and early fall and then change to a warmer dusky tan when it gets cold but they knew about it.

Deer got into real trouble here and elsewhere when the country started filling up with land-hungry pioneers. Settlers with a soddy full of hungry mouths looked at deer as meat on the table today and to blazes with tomorrow and the future of the herds. Excessive killing and habitat alterations brought about by man's activities almost exterminated the deer.

Fences have not thwarted deer expansion in state

30

NEBRASKAland

30

NEBRASKAland

32

NEBRASKAland

32

NEBRASKAland

Deer populations in NEBRASKAland are relatively stable at the present time and will probably remain so for the forseeable future. But there is a threat to their continued prosperity. Right now, this threat is small and far, far away, but it is there. Again, it is man, who may be the exterminator.

Someday, someone is going to have to ask a mighty leading question: "Which is best, another high-rise apartment here, a super highway there, a shopping center someplace else, or a herd of deer?"

Let us hope there are enough people around with enough guts to answer, loud and clear.

"Deer!"

THE END

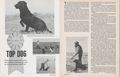

Top Dog

YOU DONT USUALLY find three retrievers from the same litter competing against each other at the National Field Trial but it's going to happen this fall. The eyes of the nation's field trial set will be on three Nebraska black Laboradors when they go after the highest honor of retrieverdom at Weldon Spring, Missouri, November 16 through 19.

Buttons will pop right off Nebraskans'vests because this ribbon-winning threesome are real crowd-pleasers. Vanspride Ebony Shadow owned by Bill Van Sickle; Jetstone Muscles of Claymare owned by Claus and Marge Johnson, all of Lincoln, and Jet's Target of Claymar, owned by B. "Bing" Grunwald of Omaha are all scheduled to make their bids at the National Field Trial for the national retriever champion crown. This trio of four-year-olds were born on the Johnson's farm near Lincoln, and Ebony, Target, and Tony, as they are called around the kennel, have led charmed lives ever since.

All three littermates have joined the elite ranks of field trial Champions. While it will be Target's first go at the Nationals this year, both Ebony and Tony gave it a whirl in 1965 at Dover, Delaware. Out of a series of 10 tests, Ebony completed three, and Tony struck through six. Both Labs were to be congratulated as there was only one younger dog entered in that Olympics of the dog world. Marge's Tony also competed in the 1965 and 1966 Amateur National Field Trial where all retrievers must be amateur-handled. While he was the "baby" of the group, Tony trotted through nine series of the 1965 meet—just a flip of the tail away from the title. This year he lasted for six series at Spokane, Washington.

When the three Nebraska littermates fight for their share of the glory in November at the Nationals, one of them will stand out as the smallest of the trio. Ebony, a gutty little bitch, rivals her brothers with tenacity. Her owner, Bill Van Sickle, a Lincoln manufacturer of plastic products, never planned for the wiggling puppy to be anything more than a hunting companion.

Four years ago Bill paid fifty dollars for the stubbed-nose little ball of black fur that has since joined the doggy elite of Field Trial Champions.

Vanspride Ebony Shadow was a long moniker to give the little bitch, but she did not waste any time living up to the pride that was invested in her. John Harciing of Lincoln, Target's original owner, offered to train Ebony along with Target. Bill gratefully turned the ever-curious puppy over to his friend, and training began when the two dogs were four months old, barely out of puppy highchairs.

Ebony and Target took to training like gray-flannel suiters to martinis. After two months of rigorous work, even John's sergeant-lusty voice began to show wear. Ebony was then entered in her first meet, an AKC-sanctioned trial in Lincoln, sponsored by the Nebraska Dog and Hunt Club. She ran in the puppy stakes and charmed the judges to win a first-place blue ribbon.

However, dogs may only run in the puppy stakes for a year. At her next meet, Ebony trotted off with another ribbon. John then decided it was time to give the rapidly-growing retrievers a taste of "working the road". For the next year and a half, Ebony and Target competed in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Tennessee, Missouri, Kansas, and Illinois. The Labs collected ribbons like the Yankees win pennants.

By January, 1964, John and Bill had to come to a decision. They had two good dogs. Should they keep the retrievers strictly as hunters and pets, or should they turn them over to a professional trainer and handler? John, an engineer for a dairy company, realized he had reached his limit with the training. But he saw the vast untouched potential in the dogs that the right trainer could spark to retriever stardom.

By coincidence and good fortune, Joe Schomer settled in Lincoln to build his dream—Schomer's Kennels. Joe, originally from Council Bluffs, Iowa, was well-known in retriever circles as the trainer for Royal Spirit Lake Duke, two-time National Retriever Champion in 1957 and 1959. Under Joe's deft handling, this New York dog amassed a total of 180 points in licensed trials before he retired to call it a dog's day. This mammoth number of field trial points broke the record held since 1939 by Black Panther with 172y2.

Ebony was the second of Joe's four-legged students in Lincoln. Target followed about five months later. Training began in earnest. Schomer drills his dogs to perfection. One fault can cost a retriever the national title because of the fierce competition at these meets. There is usually not a measureable difference between the last five dogs contending in a national trial, and it takes a faultless performance to top the judge's honor roll.

As for secret formulas to field trial success, Schomer does not believe in them. But, he underscores daily discipline. Rigid discipline can be taught to a dog even during a playful romp. While retrievers are hunters by instinct, this does not rule out continual coaching.

"Dogs are creatures of habit. You must work them in a pattern, day (Continued on page 48)

OCTOBER, 1966 35

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA...

RING-NECKED PHEASANT

Nothing that flies or runs can match the spirit and sass of this cackling daredevil by George Noson Wet Lands BiologistTHINK OF the orneriest, toughest, runningest critter that flies and you know without a doubt that there is but one upland game bird that fits the description. His scientific name is phasianus colchicus, but he is better known by the name of ring-necked pheasant

The pheasant became established in Nebraska in the early 1900's and fared very well on the same conditions which drove the prairie chickens out of much of their original range. Prairie chickens thrive on vast Grassland areas interspersed with small cultivated elds. But, as the land in eastern Nebraska yielded to the plow, so went their habitat. This increase of cultivation, however, was just the ticket for the hardy oriental import.

Today's pheasant is a duke's mixture of several Old World species. The most important of the various strains imported into the United States are the Chinese ringneck, Mongolian, Japanese, and the Common English pheasant. The hens of all the pheasant species are very similar in appearance but the cocks have a variety of color combinations.

The diet of the pheasant varies, depending on where he lives. Birds in the lake areas of Nebraska's Sand Hills do very well on the seeds of marsh plants and weeds. Studies have shown that pheasants will eat seeds and greens of more than 110 different plants. Corn is a highly preferred food wherever it is available, however, it is one of the poorest sources of calcium so other food types must be present to offset this deficiency.

Insects are an important food source for the first few weeks of the young pheasant's life and make up the bulk of his diet until he is about 10 weeks old. Grasshoppers, various types of larvae, and other insects provide the necessary protein needed for speedy development of the young.

Many thousands of sportsmen await each season's opening with anxiety but few are aware of the complex factors which can influence the quality of the upcoming season. Production of young during the spring and summer months is always the determining factor. Adverse weather is probably one of the most important factors which limits this production. Late spring rains, flooding, hail storms, and extreme drought play influential roles. Farming operations destroy thousands of nests each year. Predators are also rearing their own young at this time of year and require food for survival. Unless the hen is killed or the nest destroyed late in incubation, she will continue to renest until a brood is hatched or until time runs out. Pheasants nest in a variety of cover. One of the most preferred areas for nesting is in alfalfa fields but very few nests survive to completion due to mowing. Other cover types used for nesting include grass, weedy fields, roadsides, winter wheat, and fence rows.

Clutch size varies from about 11 eggs in early spring to as few as five or six in late summer. Incubation takes from 23 to 25 days. In Nebraska first broods show up during the last half of May.

Nature has a tendency to overproduce in spite of all the many hazards. Far more young are hatched than could ever survive into the following spring. Studies show that more than 70 per cent of a fall population of pheasants will die before the following breeding season. This loss occurs whether they are hunted or not so birds taken by hunting serve merely as replacement mortality rather than adding to this annual loss. This annual turnover qff a population applies to hens as v\ as cock birds and for this reason a limit umb#t> hens cpn safely Be agerir luction.

THE END

Fairfield Creek's riot of fall colors is bonus for angler in search of rainbow

Autumn Double

It's trophy time on Nebraska's lakes, streams. Record books bock efforts of diehards who mix fish with game by Don EversollCOOL BREEZES, brisk temperatures, and rippling waters may sound like a perfect way to describe the NEBRASKAland hunting scene this fall, but to any fisherman who plies this state's lakes and rivers, it's a direct cue to grab that fishing rod and challenge any lunker that wants to do battle.

The invigorating change in seasons sends big fish on a spree from border to border to create a bonanza that few can resist. Investigation of the state records reveals that the largest brook trout, sauger, yellow catfish, and sturgeon ever caught have been landed after October 1. Other top fish not dated in the book might well have been landed after this date, too.

An investment of $3 for an annual resident anglers permit and $5 for nonresidents will pay top dividends in dozens of reservoirs or rivers state-wide. Out-of-state sportsmen may prefer the $2, five-day license for their autumn excursion.

Even though hunting is "top dog" during the month of October in NEBRASKAland, the main topic around many sportsmen's hangouts is fishing. There are decided advantages to fall fishing. No mile-long corn rows stretch forever in front of the fisherman. While hunters are hacking through the sandburs, anglers have clear, cool lakes waiting to offer tackle-busting bass, bluegill, walleye, trout, or catfish.

Bass and walleye fishing rate the admiral's stripes when it comes to naming favorites among the fall-time species. Both largemouth and smallmouth bass inhabit NEBRASKAland's rich waters, with largemouth showing up in greater numbers. Their range extends throughout more of the state than the smallmouth, too. Look for weedy shores or brush-choked bays at Hugh Butler Lake, Harry Strunk Reservoir, Jeffrey Reservoir, the Missouri River oxbows and any one of dozens of private small ponds in southeastern Nebraska. Poppers, bugs, or noisy surface-action lures will do the trick. A hot spot near Lincoln is the Salt Valley Watershed, with Wagon Train, Stagecoach, and Bluestem lakes big producers. Other lakes supporting fishable populations of old bronze-backs are those on the

Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, and the sand pits

flanking the Platte River in the central section of

the state.

Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, and the sand pits

flanking the Platte River in the central section of

the state.

Smallmouth bass call Lake McConaughy, Merritt Reservoir, numerous Interstate-80 pits and the Bridgeport Pits home, with the emphasis on McConaughy. "Big Mac's" rocky southern shoreline is an ideal harbor for the red-eyed, slamming fireballs, and a spinner with bucktail streamer is a hot lure. Minnows could mean the difference there at times between story soup and tasty fillets on the table. There is little doubt that slab-sized smallmouths abound in the lake. The state record red eye at 3 pounds, 15 ounces came flashing from McConaughy in 1962.

At Merritt Reservoir, south of Valentine, small-mouths hang around Boardman Creek bay, and along the rocky edges near the face of the dam. Trout go on the rampage at Merritt in the fall, too. At Bridgeport, early-morning fishermen head for the middle sand pit for some lightning quick action.

Lake McConaughy, the state's largest lake at 35,000 • surface acres, is a perennial hot spot for walleyes.

Bank fishermen flash ear-to-ear grins when fellow anglers stop to ask about their luck with the walleyes. Drifters baited up with minnows, and trollers who rig spinners in front of worms do a lot of business, too. McConaughy has a history of good fortune for walleye fishermen, as the record book, again, bears out. No bigger walleye than Don Hein's 16-pound, 1-ouncer that came out of Big Mac in 1959 has ever been registered.

An army of fishermen will tell you that catfish are the No. 1 target when the leaves turn from green to gold and a harvest moon is rising in the east. Whether on rod and line, or bank lines, the whiskered lunkers furnish fine sport when they annually go on the prowl along hundreds of miles of rivers and creeks. Many anglers contend late-season appetites of catfish are even more voracious than those of bass or walleye. While this might be arbitrary, the numbers of successful catfishermen are not. When the cats are biting, the word spreads mighty fast and every available rod is put to use doffing cheese bait, liver, blood, or special concoctions in front of the waiting whisker faces. Waterfowl hunters on warm days have a special trick up their sleeve for added excitement.

They often "double" on ducks and cats by setting bank lines next to their blind in the morning, then hauling in the catch during late afternoon. Some of the popular rivers for this type of sport include the Missouri, Platte, Loup, Nemaha, Republican, Elkhorn, Blue, and Niobrara. Lakes that enjoy a good reputation for fall catfishing are Harlan, Johnson, Maloney, McConaughy, Lewis and Clark, Stagecoach, Bluestem, and Wagon Train.

Late-season trout fishing in NEBRASKAland is in a blue-ribbon league all its own, and it has a tendency to leave an angler breathless and weak in the knees. During September, spawning rainbows, most of them over two pounds, migrate from Lake McConaughy upstream into the North Platte River and from there into such famous streams as Nine Mile, Red Willow, and Winter creeks. Fishermen work these panhandle feeder creeks from October on with "strawberries", or fish eggs tied inside of a nylon patch, to tangle with their share of the brightly-colored streakers. Slip your hip waders on, sneak up to a deep hole, drift your bait into the darkest spot of the current, then cinch up your belt for one of the wildest, bone-busting scraps of your life when the line jerks sharply and that rainbow decides it's time to head back home. Always ask permission to fish, because most of the action is waiting on private property, located in Scotts Bluff and Sioux counties.

Other prime trout waters for both brown and rainbow are the Niobrara and White rivers, Monroe, Hat, Soldier, Dead Horse, Bordeaux, and Beaver creeks in the scenic northwest, Snake River and Merritt Reservoir near Valentine, and Verdigre Creek near Royal. There is also put-and-take trout fishing at Two Rivers Recreation Area, where a buck and a half flopped over the counter will give a sportsman a red tag and a chance at five trout.

Fishing is not uniquely a man's sport and this is particularly true in NEBRASKAland. Not only do women fish in this state, but sometimes they tie into world record fish. Mrs. Betty Tepner of Plainview showed the world how to do it when she landed the largest sauger ever conquered anywhere, in October of 1961. Her eight-pound, five-ounce prize was caught in the Missouri River near Niobrara. This area is a jackpot for sauger when they go on their fall feeding binge. Other hideouts are Gavins Point Dam, the Columbus Tailrace, DeSoto Bend, and the numerous oxbows on the Missouri River above Omaha.

What makes so many fish forget their easy summer pace and turn killer when Autumn rolls around? And what lures are best? Perhaps it's the approaching winter and the need for extra body fat that sends bass knifing through the water in pursuit of anything that swims. Scientists theorize that descending water temperatures trigger a response in the creature's motor that in turn tells the fish to hustle.

Poppers and noisy surface lures are dynamite on bass in the fall, and you'll be telling for a long time to come how those hungry bass catapulted with blinding speed into your plug. Late afternoon, evening, and early morning are the best times.

On the other hand, in the case of walleyes, it could be the shoreline-cruising habit of bait fish that draws lunkers close into the shore, thereby putting more fish in reach of anglers. This has been suggested in recent studies by the Game Commission at Lake McConaughy. Nets there loaded with walleye which had gorged on fingerling shad indicate heavy traffic of the fish around the dam and south shore possibly because of the presence of shad.

Regardless of the theory involved, the kind of fish, or name of lake or river, there will probably always be fine fall fishing in Nebraska. One recent experience by two outdoor companions helps support the claim that Nebraska is truly the "nation's mixed-bag capital".

Jack, an insurance agent, and Bud, who works for the railroad, packed rifles and shotguns one fall morning for a squirrel foray to the Blue River valley. At the scene, the pair filled out on chatterboxes, bagged two cottontail and a pheasant, all by mid-afternoon. In the meantime, several fat catfish took a liking to bait on some setlines. When the day was close to done the two took off for home loaded down with a potpourri of game from the valley. Ail was not over yet, though. Passing by a pothole, one of the men spotted six ducks, and thanks to an effective stalk, both hunters nailed all six of them.

This is not always the case, of course, with the majority of fall-time sportsmen. But the same chance awaits anyone with blood red enough and fishing line strong enough. Your "double" this year, too, might mean mallard and largemouth.

THE END

40 NEBRASKAland

Bee Tree

It takes a strong constitution to chop down a hummer's home, but cache of cool honey is soothing medicine if you win out by Charles ArmstrongMENTION THE wild but soothing world of nature and you've got a conversation going. It usually involves an exchange of some epic tales of adventure, ranging from man against the wilderness to hunter against a deadly animal. Not too surprisingly, you never hear too many hair-raising yarns on chas- ing wild bees. Sound crazy? Maybe so, but it's one of the wildest outings I've ever experienced.

Hunter and hunted are evenly matched for this game. Man with his ingenious hardware, ranging from scope-sighted rifle to irresistible fishing lures, often has it all over his prey. But in this game, a guy has to rely on his own resources. It takes a lot of nerve, quite a bit of know-how, and sometimes an iron constitution to take on a swarm of honeybees. The rewards are more than satisfying. In fact the cool, tangy honey is absolutely delicious.

C. A. "Big Mac" McGuire had located the hive we were to hunt in the summer while he was fishing in Bluestem Lake, a Salt Valley impoundment south of Lincoln. The lake had backed up and water-killed a grove of trees, but the bees were still holed up in one of them.

We obtained permission from the Game Commission's parks division to go after the bees on state land, as required by law, and we were ready. I might point out here, that permission is always required for this activity, either from the private landowner or the state agency involved.

My partner had picked a perfect winter day for the hunt. The ice was at least 10 inches thick, the sun was shining, and the temperature was pushing 60 degrees. Mac loaded the car with a stocked beehive, smoker, ax, and saw. He planned to use the hive to transfer the wild critters to his own bee operation. The smoker was a puffing device to pacify the honey makers. As we drove out to our rendezvous with the bees, Mac filled me in on the fine points of honey hunting.

"The tough job in honey hunting is finding a tree," my host said. "There are several ways of doing this, ranging from such complicated systems as triangulation on down to the simple but not too likely expedient of following a bee home."

Mac went on to explain that triangulation is the science of picking up the honey makers' flight line from three different localities and determining where they intersect. The bee is a straight flyer, which accounts for the term "beeline". This is the key to triangulation. If 42 NEBRASKAland you really want to get tricky, you can try sprinkling flour on the honey producer as he's nibbling head down in his source of nectar. Since the bee makes constant trips back and forth from nectar to hive you can establish a rough time pattern via his tracks.

My partner had all kinds of praise for bees. A bee man himself with his own string of hives, he explained how the critters are so wonderfully adapted for their job of making honey. Each sports a long flexible spoon-like tongue to lap up the nectar. Tube-like channels suck the nectar into the body for carrying.

When we arrived at the lake the bees were waiting. They didn't seem to rile too easily at first, but I was glad Mac had his smoker. Several times their buzzing took on a shrill, angry tone. He gently soothed them with the smoker, so we could go back to work with the ax or saw.

But the rig didn't keep Mac from getting stung. Even this didn't bother the veteran bee man. Each time he was bitten he would slide his thumbnail along the skin into the sting. The little poison bag and sticker would pop to the surface, and Mac would flick it away. Mac provided me with a head net, but he was only dressed for the weather.

After about two hours of hacking we had the water-soaked branch down on the ice. He split the log open so we could clean out the honey and the bees. Next Mac laid the honeycomb out. Taking a couple of the bigger wood chips from his chopping, he transferred the bees into the hive. Meanwhile, the sun was warming the combs, and the honey dripped slowly down to sparkle brightly on the log. I took off my gloves and picked up a chunk of the comb, pulled up my veil, and started eating like a greedy bear cub. It tasted wild and sweet and cold, as delicious as the first watermelon of the season. Once Mac had finished transferring his bees, he joined me in my outdoor repast. We must have looked like a couple of hoboes as we sat there munching on pieces of honeycomb.

After satisying our yen for wild honey, we loaded up a couple buckets and took them back to the car. The honey was dark with about a year's aging, about the color of the golden rays of the late afternoon sun. This would be a day I would long remember. My share of the honey was gobbled up long ago, and I'm anxious to join Mac on his next expedition. I would take the chance of getting stung a dozen times to get another taste of that wild, golden nectar.

THE END

SHOTGUN SHELL GAME

by Fred Nelson Lavish, or plain, smoothbore is useless toy without proper fodder. Hunter who knows pellet patterns and where to put them has best chance in Held Spread of Shot Pattern in Inches At Boring Cylinder Improved Cylinder Modified Full Various Ranges in Yards: 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 19 26 32 38 44 51 57 15 20 26 32 38 44 51 12 16 20 26 32 38 46 9 12 16 21 26 32 40LOOKING AT IT objectively, a shotgun is a pretty sorry piece of machinery. It's initial cost is usually high, it's expensive to operate, temperamental in performance, and highly individualistic. A shotgun can be compared to a custom-fitted bowling ball. It may "feel" just right to you and be as awkward as two left feet to me. Without the proper ammunition, a scattergun is practically useless since its only functions are to ignite a charge of gunpowder, control and confine the resulting explosion, and more or less direct minute spheres of lead toward a chosen target.

A shotgun is an unblushing hypocrite. If its owner has a good day in the field it accepts the lavish praise without a murmur of modesty when actually the ammunition does all the work. Furthermore, the shotgun has resisted major technical improvement for almost a century. True, it has accepted flossy trims and geegaws, pretty woodwork, and burnished metal but basically it has remained unchanged since that day in 1881, when Fred Kimball, a professional duck hunter, came up with the idea of choke to extend a shotgun's range and improve its patterning ability.

Yet with all its defects, a shotgun is still one of the most efficient devices ever invented to shoot at and hit a moving target. A sportsman may like and admire his rifle but he loves his shotgun because it is so prone jto human-like frailties.

A shotgun is and probably always will be a short-range killer. Despite fond claims to the contrary, a shotgun is basically a 40 to 50-yard weapon and any moving target hit beyond that distance is, in the final analysis, just plain unlucky.

A shotgun's killing range is largely controlled and regulated by the degree of choke present in the barrel or barrels. Choke is the all-inclusive term used to describe the amount of constriction in the barrel which compresses or bunches the shot charge together and produces proper patterns at various ranges. Choke is measured by points with a point being a one-one-thousandth of an inch difference between the bore diameter and the muzzle diameter. In the old days full choke meant 40 points or .040 of an inch constriction. Now it can be as small as .014 and still be considered full choke depending upon pattern density.

Once upon a time, chokes wore the descriptive terms, of full, three-fourths, one-half, and one-fourth or quarter choke for a strong improved-cylinder. Today, we use the terms, full, modified, improved-cylinder, and cylinder to describe the borings. There are two other degrees of choke which are referred to as Skeet No. 1 and Skeet No. 2 but these are of primary interest to that special breed of gunners called skeet shooters. Skeet No. 2 usually delivers modified patterns while Skeet No. 1 is basically a cylinder bore. An idea of how the various chokes influence patterns can be seen in the chart at the bottom of page.

A man who. is going to do all of his shooting at 40 yards or more will probably be better off with a full-choke gun since the pattern spread is 40 inches. Now 44 NEBRASKAland taking the average number of No. 6 pellets in a 12-gauge 2% inch shell, this means that 28 pellets are splattering in there and there won't be very many blank spaces. At the other extreme the cylinder bore is spreading its shot over 57 inches and there is at 40 yards bound to be more distance between pellets perhaps enough to let the bird or clay target sail through untouched.

1...1But let's Pause a bit and make these figures a little more confusing. An adult pheasant offers about 14 inches of vital body area, a bobwhite about 5, so it s obvious that all of those 281 pellets aren't going to smack into the pheasant or quail; there simply isn t enough space enough for them so a lot of the pellets are going to continue their merry way through the wild blue yonder. Besides, shot strings out in cigar-shaped procession and the tailenders never catch up to do any damage. If the bird is hit with the front of the string he drops below the path of the late-comers so only a relatively small percentage of the shot actually does the work.

Not all hunters ride out their targets to 40 yards before touching off the smoke pole. By far the greater majority shoot or attempt to shoot right now once the bird is in the air so let's see what a full-choke pattern is doing at 25 yards. Its shot pattern covers 21 inches and unless the gunner holds "tight" he's apt to miss since there is quite a margin of error. In other words he s throwing a baseball at a gnat and the two might not collide. With the modified boring, the pattern spread is 26 inches so the "ball" is bigger and its chances of hitting the gnat are improved. By and large experienced hunters favor the modified boring for upland game and the full choke for pass shooting at waterfowl.

Choke markings on a barrel can be confusing since ammunition varies greatly. A gun marked modified may shoot exceptionally tight patterns with a certain brand of ammunition and a certain shot size Conversely it may deliver wide-open patterns with another brand and another shot size so the only way to know for sure is to pattern your shotgun with the shells you are going to use and find out exactly what they are going to do. Plastic shells seem to produce tighter patterns than the older paper hulls.

Patterning isn't hard but it does take time Tack up a sheet of paper about four feet square and mark a bullseye in the center of it. Measure off 40 yards aim at the bullseye, and shoot. Then enscribe a 30-inch circle to include the most pellet holes and count them Compare the number of pellet marks in the circle with the total number of shot in the shell and work out your percentages. One pattern means nothing; five will give you a fair average, but 10 is even better. Practically any ammunication handbook will give you the number of pellets m a shell but if you haven't got one, cut up a shell and get the kids busy counting the little spheres It may take considerable experimenting but sooner or later you 11 come up with just the right combination of shell type and shot size for good, solid patterns.