OUTDOOR Nebraska

February 1964 25 cents Ice Anglers Fly to a BIG-BASS BONANZA page 12 WINTER BOWMEN DE SOTO BEND JACK POT DEER PATROL

OUTDOOR Nebraska

Selling Nebraska is your business February 1964 Vol. 42, No. 2 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor J. GREG SMITH, Managing Editor Bob Morris, Fred Nelson PHOTOGRAPHY: Gene Hornbeck, Lou Ell ART: C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, Frank Holub ADVERTISING MANAGER: Jay Azimiadeh

WEED-PATCH Symphony

Hunters face the music when 'hounds sing and the bunnies jigBEAGLES, BUNNIES, and boys make an unbeatable combination. Beagles are four-legged musical instruments. Bunnies, of course, are cottontail rabbits who lead beagles in their weed-patch symphonies. Boys are from 8 to 80, school lads to bank presidents, who find dogs and rabbits irresistible.

My quest for the bunnies took me to Murray one bright Saturday morning early in January. The conductor for this symphony was Jim Conway of Fort Crook, who brought along his beagle musical trio of "Gardenia", "Salvia", and "Music". He was assisted by his 15-year-old son, Dan, along with brothers Ross and Charles Thomason. Both took the day off from their farm near Plattsmouth. We selected a creek bottom north of town for our weed-patch symphony.

The dogs came out of the tail gate of Conway's

station wagon wagging their tails with anticipation.

Fortunately, the dogs' short legs slowed down their

FEBRUARY, 1964

3

enthusiasm to a pace we could match. They sniffed

and wiggled their way for nearly 100 yards before

hitting a trail. Music let out a yelp that sounded

like a car skidding through a busy intersection. The

other two joined her and they went to work in earnest.

enthusiasm to a pace we could match. They sniffed

and wiggled their way for nearly 100 yards before

hitting a trail. Music let out a yelp that sounded

like a car skidding through a busy intersection. The

other two joined her and they went to work in earnest.

The trail must have been old, as the dogs ran out of scent in a few minutes. "They may be too excited right now," Jim explained. "As soon as they settle down we'll be in business."

Jim, a civilian mechanic at Offutt Air Force Base, has been raising beagles for the past 19 years. To him a bunny hunt is to watch and listen. His usually serious expression melts into a grin whenever the dogs hit a trail.

"Listen," he said, "Gardenia has got a hot scent now. She's a real worker. The little gal won her first licensed field trial when she was less than a year old and became a field-trial champion before she was two."

Salvia bawled out in chorus with Gardenia, followed seconds later by Music. Jim figured the dogs would take the bunny in a circle, then bring him back right about where they picked up the scent. We were about 50 yards down the creek bed situated on a low hill that gave an unobstructed view of the proceedings.

WEED-PATCH Symphony continued"Keep your eye on that small bush," Jim ordered when he saw a quick movement to the left. "I think I saw the rabbit. He'll stay there for a minute before moving on."

When chased by dogs, a cottontail doesn't blaze through the brush like a rocket. Instead, his flight is slow and deliberate. His home territory takes in less than an acre and he'll spend his whole lifetime there. Every tree, stump, and blade of grass is as well known to old hotfoot as the back of his paw. He's got speed to burn, but prefers to rely on his superb hearing when rattled out of heavy cover. Like most, ground animals, a rabbit takes off away from his home when surprised, trying to lose his pursuers far away from his form.

A cottontail will throw as many checks in his

flight as he can, stopping every so often to back

track and then take off in another direction. Sure

to Jim's words, our cottontail backed off a few steps,

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

then hopped to the left before taking off in his original direction.

then hopped to the left before taking off in his original direction.

The dogs kept up their chopping and bawling in the distance, getting closer all the time. They burst out of the draw. The rabbit's check stopped them for a minute, but they untangled the scent and were gone.

There was a shot by one of the Thomason's to end the chase. While the dogs were getting started on the next rabbit, Jim went over some of the hunting tricks.

"Your best bet is to station yourself near where the cottontail has been and wait, particularly in heavy cover like this. He'll be back pretty soon. Except in open cover or when pushed hard by dogs, the rabbit will take his time moving from place to place. He'll use his hearing to figure out where the dogs are. Actually, a rabbit has weak eyes, and as long as you don't move, you stand a good chance of him stopping well within range."

Cottontails have a reputation for being dumb. Hunters often tell of shooting at one two and three times with a rifle without the animal seemingly knowing what's going on. A shotgun blast, by contrast, will set them off in a hurry every time.

It isn't hard to find a good hunting spot. Just look for a brushy area close to grass. The brush provides cover and the grass, the cottontail's favorite food. Even better would be a small stream with a grainfield on one side and an orchard on the other. Jim pointed out a real hot spot as we walked along the edge of the creek. A farmer had cut down some trees and piled the tops close to an alfalfa field.

I kicked the brush as we were waiting for the dogs and a rabbit broke out, his bobbing powder puff tail like a beacon as he high tailed it for the creek bottom. Music picked up the scent first, letting out a chop like she had just stepped on a rusty nail. Her companions chimed in and the trio beat their way out of sight but hardly out of sound.

That's another advantage to a beagle. You can spend most of the time consumed from getting the rabbit up until it returns without seeing a thing. But the dogs fill in the blanks. You hear the cottontail's path through the maze of cover. A confused trio of bawls and chops is where the rabbit stopped to rest and look. A back track is punctured by shorter yelps, as the dogs argue out between themselves which trail is the right one. When everything is going right and the trail leads straight and true, the music is short and sweet.

Back in the 16th century, beagles came anywhere from 5 to 25 inches high at the shoulder. The modern breed is divided into two classes, 13 and 15 inches. Beagles are the most numerous dogs in the hunting classification. They rank second in American Kennel Club registrations, with nearly seven times as many as the next hunting breed.

A beagle is 25 pounds of friendship covered with a multicolpred coat of blacks, browns, and whites all mixed together so that no two look exactly alike. His floppy ears and always-wagging tail make him a favorite even with those who never hunt. Even after a hard day of hunting, this low slung projectile is ready for another bunny.

It isn't uncommon for hunters to get infested with a beagle's enthusiasm and pass up shots just so they won't spoil all the fun. By the time the shadows were lengthening, we had three cottontails in our bag. The shots we missed were anything but wasted. They just made for another round of music with the beagles chasing the bouncing cottontail.

THE END FEBRUARY, 1964 5

mari sandoz... a Living Legend

Nations leading western author is the acclaimed Voice of Nebraska by Elizabeth HuffNECKTIE PARTIES, tar-and-feather sessions, and six-gun showdowns between settler and rancher—this was the panhandle at the turn of the century. Growing to womanhood in this untamed frontier was Mari Sandoz, destined to become the voice of Nebraska and the Old West.

Hers was the untamed Running Water on the

Niobrara, an unrelenting wilderness where Indians

still roamed and virgin prairie grasses had just

felt the bite of the plow. And Mari was there to

record the scene. Thanks to her, Crazy Horse's war

cry will be heard over the plains, the Cheyenne

braves will stage their last desperate bid for survival,

and her father, Old Jules, will dream of empires.

braves will stage their last desperate bid for survival,

and her father, Old Jules, will dream of empires.

These are but a few of all those characters and events Mari has penned into posterity. Her list of best sellers would fill a bookshelf, but the industrious biographer writes on, seeking out all those whose story should be told.

Those who knew the scrawny sunburned homestead girl of the Running Water would find it hard to believe that she would become one of the nation's leading authors. Mari considered herself lucky in getting an eighth grade education, an education that was ever-stymied by Old Jules, her idealistic and stern father. The oldest of six, Mari was expected and did the work of a man.

Practically from babyhood she was given responsibilities. As the eldest, she was left with the young ones all day, beginning when she was only five.

"By the age of seven," she said, "I was sometimes left alone with them for two days and nights when our parents went to town. Whoever was the baby was put into my cot in the attic at two weeks and from then on was mine—to bathe, care for, spank, and love."

An adult before she had a chance to be a child,

little Mari took refuge in her books, although' her

8

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

father had forbidden any fiction in the house. But

she managed to hide her treasures away.

father had forbidden any fiction in the house. But

she managed to hide her treasures away.

From these she learned the wonders of the world of literature. And from the stories told in the Sandoz home, as she listened to the Indians, trappers, and settlers, she learned the wonders of the world about her.

"By seven," she said, "I knew other things, too. My father was a good friend of the Sioux and the remnant of the Cheyennes who lived with them since the outbreak of 1878. I had also seen much of the settler-cattleman fights.

"But we were taught a wonderful at-homeness in the world and universe by this violent father. We learned the meaning of every change in sky and earth. At seven I knew the theory of spontaneous generation, something of spiral nebulas, and that there was enough latent energy in the atoms of a handful of sand, if released, to do all the hated tasks of washing, ironing, housework, and hoeing for my lifetime.

"I knew the lead to take on a wild goose on the wing, or a grouse, and how to catch a mink, weasel, coyote, or eagle, and how to remove the pelt and cure it."

By the time she was 10, Mari was already submitting stories to the junior page of the old Omaha Daily News. Her efforts, when first published, only earned her a whipping and banishment to the cellar. Thereafter, she used pen names on her work until she was grown and away from home.

Her formal schooling was limited, but she finished eighth grade. Mari went on to teach country school for five years until she was old enough to enter the University of Nebraska as an adult special student.

When Mari was 14, she and her brother, Jules, were sent to search for cattle that had drifted in a May blizzard. "We saved all but a few by digging them out of the snowbanks before they became too chilled," she recalled. "But it took a solid day, and by night I was snow-blind—totally blind for around six weeks. Then I discovered that I need never close one eye to aim a gun again. I had only one eye left. It is a very useful one, so it doesn't matter."

The West could have lost a champion and the world a brilliant writer had this youngster of the Sand Hills accepted an offer extended when she was a teenager. Mari was approached by a scout for a Wild West show with an offer of a job as a girl show rider.

"I did ride a great deal," she recalls, "but I was certainly never pretty in the saddle. I rode like a cowboy, the easiest method, using the old axiom for the trot, 'Sit it slow and stand it fast, makes both man and horse to last.' "

The youngster who saw blood shed by both ranchers and homesteaders near her home along the Niobrara possessed a dogged determination. She not only stood up against the objections of her father, but withstood the long series of rejections by publishers that seem to be a young author's fate.

Her first book, "Old Jules", the biography of her father, was five years in the offing—three years for research and two years to write. All the while she held night jobs to put bread on the table and leave her days free for research. The manuscript then made its tedious way through 13 publishers before accepted by Atlantic the second time around. The book then won the Atlantic $5,000 nonfiction award in 1935. Her career was under way.

"Old Jules" has been reprinted in other countries and in several languages and has won more awards. But it was only the first of 17 published books and numerous.other articles and stories of the changing West. No. 18, "The Beaver Men", comes off the press in 1964 and is chronologically the first in her Plains Series.

Future plans include an autobiography on which she is constantly working, in addition to her other efforts, and filing the material away. "The files are becoming quite bulky as I remember and jot things down," she chuckled.

There are other recollections, too. "I've had hair cut from my head twice by gunshot, once intentionally, once accidentally, but (continued on page 40)

FEBRUARY, 1964 9

DEER PATROL

Spotlight surveys keep track of how hunting affects game by Fred NelsonIN THE REVEALING rays of the spotlight, the big buck stands like a tawny statue against the backdrop of a winter night. Inside the darkened car, the driver's right hand gropes for a metal object on the seat. As his fingers close over smooth steel, he lowers the car's window. Slowly he rests it on the window ledge and takes a bead on the light-hypnotized deer.

"By golly, the old boy made it," the man mutters, as he peers through the powerful lens of the telescope. With an abrupt gesture he switches off the spotlight. The spell broken, the buck bounces away, with the frost-stiff grass crunching under his hooves.

A jacklighter scouting a mule deer for a future illegal kill? No, a Game Commission technician is making his annual postseason survey in a deer management unit. Information gleaned from many nights of patient watching will be used when the Game Commission establishes the seasons for next fall's hunt. In 1963, pre and postseason deer surveys were made in the Keya Paha and Pine Ridge units.

The preseason surveys are carried out in September and early October. Then the fawns accompany their mothers on the nightly feeding forays and the bucks show the rutting interest. The postseason checks are done in November and December before the bucks lose their antlers.

Counts before the season are useful in establishing buck-doe-fawn ratios.

They give technicians an estimate of the unit's total deer population when used

10

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

with other census-taking techniques. The surveys

are made on several nights under varying weather

and visibility to strike an average. A tally is kept by

sex and species.

with other census-taking techniques. The surveys

are made on several nights under varying weather

and visibility to strike an average. A tally is kept by

sex and species.

The Keya Paha area is about 75 per cent mule deer and 25 per cent whitetails. Mule deer are pre-dominant in the Pine Ridge. The proportion of whitetail to mules there, however, is shifting in favor of the whitetail. Technicians claim the higher reproductivity and wariness of the Virginia deer are responsible for their increase.

During the count, technicians drive 20 to 50 miles and visit at least three known concentration units each night. Alfalfa and grainfields are favorite feeding places. Once the spotlight reveals the animals, binoculars and powerful spotting scopes come into play.

Last year, 449 animals were counted during the preseason survey in the Keya Paha unit. Spotlighters found a ratio of 34 bucks to 100 does to 79 fawns. Although kill figures for the unit are still being compiled, there are indications that bucks represented 45 per cent of the total kill. The unit had an any-sex season in 1963.

The postseason survey tabbed 272 deer with a sex ratio of 23 bucks to 249 antlerless deer. Fawns were not counted since the youngsters are now approaching adulthood. Hunters' rifles are largely responsible for the sharp drop in percentages of bucks to the total herd. Before the rifle season, bucks made up 17.7 per cent of the total deer checked. After the season the percentage was down to 8.4.

Not all of the deer escaping the bullets and arrows of the hunters will be around next spring. Some will die on the highways, others will succumb to natural causes, but most of them will survive the winter, barring a calamity.

Surveys reveal some interesting facts about deer and their habits. Technicians confirm the hunters' contention that whitetails are more cautious and wary than mule deer. The big-eared critter often freezes in the glare of a spotlight, and even after his break, he'll stop after a short dash to wait and watch. The whitetail isn't curious, once on his way. He keeps going until there is plenty of landscape between him and the disturbance. Bucks of both species grow wary in direct proportion to their age, with old whitetails becoming almost super cautious about revealing themselves.

Whitetails seldom venture far from the security of brush and timber. The mule is more inclined to graze toward the center of an alfalfa or winter wheat field. This species often ghosts through the cover while the mule deer charges. Whitetails give open areas a real look-see before crossing, but the mule deer is more impetuous.

Technicians know that whitetails breed younger than their western cousins. An examination of whitetail yearlings revealed almost every one pregnant. The mule deer waits until after her first birthday to accept the responsibilities of motherhood. Mule fawns stay with their mothers longer, creating the hunter fallacy of "dry" does. Hunters seeing two does shepherding one fawn believe that one is barren and is serving as a foster mother for another's fawn. Actually, the second doe is not yet ready to breed.

As the year wanes, both species become bolder in their feeding forays. Corn, alfalfa, winter wheat, and rye fields are favorite feeding grounds as natural greenery is decreased. As the year ends, more and more deer congregate in preferred areas. Farmers in the Keya Paha unit have reported herds of 100 animals. Technicians prowling the roads in the same area have counted 67 animals in one group.

Wind makes both species spooky. When the wind is brisk, observers find fewer deer feeding. Apparently the animals prefer seclusion and an empty stomach to the cold knife thrusts of a Nebraska wind. On moonlit nights the animals are spooky and nervous, making accurate counts difficult.

In their studies, the technicians learned that survey proportions of whitetail bucks to total population will be far below the actual proportion due to the wary and secretive habits of the males. Mule ratios are fairly true. Surprisingly, deer concentrations are often greater in (continued on page 37)

FEBRUARY, 1964 11

BIG-BASS BONANZA

Biting mad, Hackberry's lunkers take all ice clan has to offer by Gene HornbeckTHE BOY couldn't have been more than four years old. Bundled against the wintry blasts of January, he resembled a tote sack standing on the ice. A knitted toque protected the boy's face. His eyes squinted against the glare of the winter sun as he watched the dancing float on his ice-fishing rig.

Little Pat McGuire was about to get an introduction to ice fishing, or at least some of its excitement.

The Thedford youngster raised the short stick

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

and then let the lure settle quickly until it was

stopped by the cork. A torpedo-shaped shadow

flashed under the ice of Hackberry Lake. To Pat's

surprise, a big pike opened his tooth-studded mouth

and almost inhaled the small jigging spoon.

and then let the lure settle quickly until it was

stopped by the cork. A torpedo-shaped shadow

flashed under the ice of Hackberry Lake. To Pat's

surprise, a big pike opened his tooth-studded mouth

and almost inhaled the small jigging spoon.

Pat saw the cork plunge out of sight and he pulled

as mightily as a four-year-old could. The big northern shook his head in panic as the hook bit deep into

his jaw, then slammed for cover, traveling a foot

before hitting the end of the short line. Pat tugged

harder, his eyes flashing with excitement. But his

line couldn't take the strain and snapped, leaving

FEBRUARY, 1964

the boy sitting on the ice with a look of wonderment

on his face.

the boy sitting on the ice with a look of wonderment

on his face.

The boy's battle caused quite a stir with the ice-fishing clan gathered on Hackberry. But it wasn't the first time a big pike had cleaned someone's outfit. A carnival air prevailed over the lake located deep in the Sand Hills on the Valentine Waterfowl Refuge. Largemouth bass were seemingly going

crazy, with hundreds being taken. Young and old

had flocked to the lake in hopes of getting in on the

bonanza.

crazy, with hundreds being taken. Young and old

had flocked to the lake in hopes of getting in on the

bonanza.

Fishing had been fantastic for better than two weeks before I was able to get on the scene. It all started when Corky Thorton and Gordie Kramer of Valentine hit pay dirt the day before Christmas. Four days later the pair returned to the lake and landed 19 bass in only two hours. The rush was on, first from Valentine, then from Broken Bow, Thedford, Halsey, Ainsworth, Bassett, and other towns. Over 200 fishermen were checked the first weekend in January. They hauled in over 1,500 gamesters.

Fishing on the refuge lakes has a unique aspect. Minnows are prohibited to keep rough fish from becoming numerous. This was somewhat of a hardship until anglers began successfully experimenting with spoons, ice flies, and other artificials.

Carroll Roberts of North Platte and Sid Mayhew of Ainsworth were getting full service from their batch of artificial enticers. Each was fishing from a portable ice shack and doing well on hungry largemouths. Between the two, they had seven in two hours of fishing.

But almost everyone had fish. So intent were all on fishing that little heed (continued on page 36)

COY DUCKS

Staunch friend of waterfowlers, these foolers are old as huntingSHIVERING IN the half-light that precedes the dawn, the hunter sets out his decoys. With his thoughts on the day ahead, it's doubtful that he realizes that his ritual is almost as old as time itself. Though decoys and hunting techniques have changed, the hunter is still playing the game of trying to outwit his prey.

No one knows who made the first decoy. Ancient ruins show their use in Greece, Egypt, and China. These fakes were used to lure waterfowl within throwing distance of clubs and stones. Early hunters who used nets towed the decoys near shore, hoping to bring the birds close enough for a strike. Man had the ability to lure waterfowl but lacked efficient means of killing the birds.

Excavations near Lovelock, Nevada, revealed the

use of decoys here 2,000 years ago. These were made

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of reeds woven in the shape of a duck or mounted

skins stuffed with grass. But the Indian had the

same problem as the hunter in Egypt. Ducks were

plentiful and easy to decoy, but his bow and arrow

almost made waterfowl hunting a waste of time.

of reeds woven in the shape of a duck or mounted

skins stuffed with grass. But the Indian had the

same problem as the hunter in Egypt. Ducks were

plentiful and easy to decoy, but his bow and arrow

almost made waterfowl hunting a waste of time.

As civilization progressed, so did the art of taking waterfowl. Hunters in coastal countries in Europe became very proficient with nets. Birds were driven into the nets along ponds and rivers by men in boats. The word "decoy" came about then, but it meant a duck cage or trap.

Later domesticated ducks were used to entice waterfowl into these cages. With the development of firearms in the 18th century, trained "coy" ducks were used to bring their wild brethren within range.

The full development of decoys and waterfowl hunting parallels the settlement of America. The birds were in vast numbers and guns available to all. Some of the early decoys were ingenious for their simplicity. By splitting a log, preferably cedar, the maker had two bodies. A roughly-carved head, sometimes nothing more than a forked stick, was attached. The fake was charred over a fire for coloration. Silhouettes were also popular. These were either stuck in the shore or attached to either end of a board like outriggers and floated. At this point the abundance of waterfowl made more realistic models unnecessary.

Gradually decoys became more sophisticated. Individuals with a knack with tools and a knowledge of waterfowl began to take over and decoy making gradually became a minor coastal industry.

Boats were needed to get out to the open water where waterfowl congregated along the coast. Up to 400 decoys were necessary to bring in the large flights of canvasbacks, redheads, and bluebills. With weight a premium in the hunter's boat, hollowed decoys became popular. Painting was done in bold colors to make the lure stand out. Besides, a man with upward of 500 fakes in his spread didn't have time to play Rembrandt.

By the 1800's professional hunting was big business. A Diamond Jim Brady would no more think of sitting down to a meal at Delmonico's without a fat canvasback than passing up his favorite champagne. Wild duck dinners were the order of the day and market hunters went to work with a vengeance. Until 1918 when their hunting was outlawed, professionals shot waterfowl by the millions.

Market hunters and decoys plied their deadly trade from Maine to the Carolina's. Surprising enough, decoys were never popular in the Gulf states. Hunters there stalked the birds in their wintering spots where fakes weren't too important. About the only decoys to come from this region are rolled up newspapers used to draw snow geese.

Market hunting was a thriving business in and around the Great Lakes. Sneak and layout boats were the way to go after high-priced canvasbacks and redheads. Since hunters there didn't have the same rough water to face as Easterners, decoys were larger. Decoys were high-sided and more box shaped and the heads were further back on the body.

When market hunters weren't knocking off canvasbacks, they worked on their decoys. Knot-free white pine was hard to come by and a skilled artist would go through piles of wood to find just what he wanted The logs were cut to the proper length and split lengthwise. A good man with a hand axe could rough out a body in less than five minutes. A narrow-bladed drawknife brought the body to completion. No template was used, the maker relying on his skill and trained eye. The finished product was crude compared to fancy models but was made to use, not to look at.

Former market hunter, John Ososkie of Wyandotte, Michigan, was once shown a beautifully carved and painted decoy. He summed up the market hunter's outlook when he said, "It's pretty but won't be worth a nickel for (continued on page 37)

FEBRUARY, 1964 17

MINNOW'S THE NAME

Midget to monster, these morsels are all members of luring clanWHAT IS a minnow? They come in a wide range of sizes. To anglers they are something you buy a dozen of before going fishing. There is hardly a fisherman who hasn't used minnows for bait, yet only one in a thousand can tell one from another.

You can find minnows nearly everywhere there is water. They are a staple item in most bait shops. Minnows are found even in the home or office. Some gourmets consider them a delicacy, and discriminating fish go for them in a big way, too.

Minnows are members of the Cyprindae family, one of the largest and most complex varieties of fish. There are over 300 types of the fresh-water clan in the American continent and about 36 varieties in Nebraska. Adults range from less than two inches in length and weigh but a fraction of an ounce to monsters over three feet long that heft the scales at 50 pounds or better.

These fish have many common characteristics.

They have a scaleless head, a stomach which is

FEBRUARY, 1964

19

merely an enlargement of the intestine, and a toothless mouth. With the exception of carp and goldfish,

all have spineless fins and a short dorsal fin with 10 or less rays. Minnows feed on the same foods

as the young of other fish. Some even feed extensively on algae and aquatic plants.

merely an enlargement of the intestine, and a toothless mouth. With the exception of carp and goldfish,

all have spineless fins and a short dorsal fin with 10 or less rays. Minnows feed on the same foods

as the young of other fish. Some even feed extensively on algae and aquatic plants.

Most of the minnows found in Nebraska are natives. Though fresh-water streams are their bailiwick, some are found in landlocked lakes, generally getting there during floods or by having been dumped in by fishermen. Minnows are often placed in lakes by individuals who mistakenly believe they will provide extra food. The predator-prey balance can be upset. Certain rough fish that resemble minnows also can be introduced.

Minnows exhibit a variety of spawning habits. Some species make nests under boards, stones, and other objects, with the male guarding the nest. Others bury their eggs in gravel, then forget them. Still others, mostly carp, broadcast eggs on the bottom or among vegetation before deserting their seemingly helpless offspring.

As any fisherman with a full stringer will attest, small fish form an important link in the food chain of most predaceous fish. The minnow tastes great to everything from crappie on up. To the dismay of waterfowl hunters, some ducks also find minnows a delectable meal.

The carp is the best known of the clan. When first introduced into Nebraska waters in 1881, he was supposed to be a panacea for bad fishing and an important food item. Within a few years the picture changed from bright optimism of a proud industry to despair. Although carp were stocked only in private ponds they soon found their way into streams.

It is no accident carp grow to such size. They

eat almost everything in sight, including eggs of

desirable game fish. They further destroy the supply

of game fish by rooting up aquatic plants necessary

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

for spawning of some species. To make matters

worse, they muddy the water, cutting down food

production.

for spawning of some species. To make matters

worse, they muddy the water, cutting down food

production.

Carp play a part in the commercial fishing industry, but it is doubtful if this equals money spent in an effort to rid them from lakes to make more room for more desirable game fish. Carp are the largest minnows, sometimes reaching as much as 50 pounds with 25 to 30-pounders common.

Goldfish have also caused problems. Colorful in home aquariums, this member of the minnow family sometimes finds his way into lakes and streams.

The most important member of the minnow family from an economic standpoint is the fathead minnow. It is doubtful whether most anglers could tell a fathead from other minnows, but he's probably the most frequently found member of the family in bait shops. He usually reaches about three inches.

Highly tolerant of varying habitats and water temperatures, the fathead is one of the easiest to raise commercially. Under ideal conditions nearly 300 pounds of fatheads can be produced in an acre of water. Females spawn about every two weeks when the water temperature is 75° to 80°. Then they lay from 200 to 500 eggs. In one instance, a female yielded 4,144 offspring in 11 weeks and spawned 12 times.

Its ability to take the wide range of temperatures in minnow buckets and the knack to stay alive on the hook better than most minnows makes the fathead a favorite with anglers. He's dark olive above, with a tinge of copper or brass behind the head and often along his sides. During the breeding season, his head gets rather large, but the rest of the time it's no fatter than any other minnow.

Most anglers and game fish can't tell one minnow from another and probably care less. But both agree these small darting fish are important. Without them a lot of fish would go hungry and more anglers would return home empty-handed.

THE END FEBRUARY, 1964 21

WINTER CLAIMS THE LAND

All seems barren, but nature's boutgy has food and shelter for wild inhabitants that fly, run, or swimBARREN AND lonely in the embrace of winter's shroud, the things of the earth have a beauty and strength that is uniquely their own. You'll find them in the tinkling voice of melting ice and the jeweled tapestry of snowy stream. There's light and shadow and beauty, too, in the white tattoo of a rabbit's passage and the glistening flash of a darting bird. There's promise for the future in the yucca's jaunty green challenge to the white. There's poetry in the sigh of forgotten leaves and the graceful bend of snow-laden bough.

Strength flows from the angular gauntness of

weathered farmstead and march of spidery fences,

from the glow of steamy smoke against the aging copper of the evening sky, and the cheerful promise of a

curtained window. There's strength and beauty and

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

something very precious in the music of children at

winter play.

something very precious in the music of children at

winter play.

Winter's beauty is sometimes bold, sometimes elusive, sometimes brusque, and sometimes shy. It shouts and whispers and sings its presence with crashing brass and haunting strings. In calm or storm, in brutish fury and gentle mood, in morning light and evening dusk, winter claims the land.

THE END

DE SOTO BEND JACK POT

OUTDOOR ENTHUSIASTS hit the recreation jack pot when DeSoto Bend became a national waterfowl refuge. The seven-mile lake above Blair was formed when the Missouri River was rechanneled to eliminate this oxbow so bothersome to navigation. Though waterfowl management is its primary purpose, DeSoto Bend offers fishing, boating, camping, sight-seeing, and picnicking opportunities when waterfowl aren't utilizing the area.

Fishermen from both Nebraska and Iowa were quick to move into the refuge when it was opened to angling. DeSoto offered them a prime recreation area almost in the shadows of metropolitan Omaha. No longer would they have to drive long distances to fish if the lake proved a producer.

Making a going fishery out of DeSoto Bend is a big job, one that requires the co-operative efforts of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and game departments from Nebraska and Iowa. The first consideration of technicians from the three agencies was to preserve the lake. The low dike that cut off the lake from the Missouri proved incapable of holding back flood waters in 1960. Then more than 250,000 cubic yards of sand and silt were dumped into the oxbow. After a high dike was constructed and the lake dredged of flood wastes, DeSoto Bend's future was assured.

A survey of the lake's fish population was a basic need to sound management, and it will be a recurring one. Periodic sampling had been carried out during 1961 and 1962, but it wasn't until last May that a full-scale operation could be conducted. Equipped with electric shockers, seines, gill, trammel, and hoop nets, technicians from the three agencies began a week-long survey.

At this time the lake was open to public fishing.

Certain types of the sampling equipment can be

damaged by outboard propellers, so it was necessary

to set nets just before dark and pull them in at daylight the next day.

Even then, men had to be placed

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

at strategic locations in order to warn the early and

late fishermen. Sampling was carried out day and

night to assure an accurate count, since some species

move into shallower water at night to feed while

others move to deeper water.

at strategic locations in order to warn the early and

late fishermen. Sampling was carried out day and

night to assure an accurate count, since some species

move into shallower water at night to feed while

others move to deeper water.

Fish were captured by all the sampling devices. They were measured and weighed and scales were taken. Then all desirable fish were returned to the water. From this information it will be possible to study growth in former years and determine to some degree the success or failure of natural reproduction.

As the week went by, it could be seen that the legacy of fish that the lake inherited from the river was both a bad and good one. Many rough fish, such as shad and carp sucker, were present. Yet the small sauger and walleye that were trapped in the oxbow had grown well.

Though all of the information gathered has not been analyzed, much has already been learned. Reproduction of the walleye and sauger, for example, has been almost nonexistent since the lake was cut off and protected from flood waters. The flowing river is probably needed in some way for these fish to reproduce in numbers and justifies an attempt to maintain the population by stocking large numbers of small walleye. The success or failure of the planting program will be evaluated by future surveys in the oxbow.

A full-time creel census clerk was on duty throughout the 1963 season. All cars were stopped when leaving the area. People were asked what activity they had participated in. If the visitors had been fishing, all fish were weighed and measured. It was determined how long they had fished and with what technique. Facts from this creel census allows the calculation of total visitation, the extent of participation in each activity, and peak-use periods. These figures are indispensable in planning future improvements.

The information secured from the fishermen facilitates the evaluation of how the fishing was, what the total harvest was, and what kind or kinds of fish supported the fishery. This knowledge can then be used, among other things, for determining what parts of the fishery should receive major attention for improvement.

From May 1 to September 15, 1963, approximately 178,250 people visited the refuge. Picnickers and sight-seers made up about one-half of the total. Pleasure boaters and swimmers made up one-sixth of the visitations. About one-eighth were fishermen, with the balance participating in such activities as mushroom hunting and nature hikes.

The 23,000 fishermen caught nearly 25,000 fish, averaging a little better than one fish a piece. The period of the best fishing was between May 1 and June 1, and probably this will be true next year. Crappie made up the greater part of the catch, at least by numbers.

Residents of Nebraska provided about 55 per cent of the total visitation, Iowa, 43 per cent, and other states, 2 per cent. Approximately 90 per cent of all Nebraska visitors were from Douglas, Washington, and Sarpy counties.

DeSoto Bend is a revamped river. It is a lake located in a zone of primary need. Surveys such as these will help guide preservation and improvement, not only at DeSoto Bend, but on similar projects as well.

THE END FEBRUARY, 1964 29

WINTER BOWMEN

Archers beat the cold with warm sessions on indoor shooting rangeARCHERS ARE more fortunate than their gun-toting brothers. When seasons end most gunners reluctantly put away their equipment until next year. The bowmen gather up their gear and move indoors to continue twanging the bow strings until spring.

More adaptable to indoors than gunning, archery is really a year-round sport. Competitive bowmen will be using indoor ranges to sharpen up their skills for the big Nebraska State Indoor Archery Tournament in March. Shooting-for-fun and hunting bowmen use the range for practice and to trade tales about past experiences and future plans.

Biggest problem for the steam-heated disciples of William Tell is finding a place to shoot. At least 20 yards from shooting line to target butts are needed.

Indoor bowmen shoot various rounds, following a formalized routine with a prescribed number of arrows fired at various ranges. Among the more popular rounds is the "Chicago", fired at 20 yards. Here the archers line up their arrows on a 16-inch target, striving to put the shafts into the "gold", a center bull's-eye 3-3/16 inches in diameter. Any hit outside the white ring is the equivalent of the rifleman's "Maggie's Drawers", a big, fat miss.

The "Duryea", fired from 30 yards at a 24-inch

target with the scoring areas correspondingly larger

than those of the Chicago target, is another popular

round. So is the "Flint", fired at staggered distances

30

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

at various sized targets. Each sequence of arrows

is called an "end" in bowman's lingo.

at various sized targets. Each sequence of arrows

is called an "end" in bowman's lingo.

Twenty-six clubs are functioning in 23 cities in Nebraska. Omaha heads the list with three. Other communities include Lincoln, Fremont, Beatrice, Grand Island, Norfolk, St. Paul, Albion, Hastings, Holdrege, Arapahoe, Beaver City, Oxford, Kearney, Lexington, Cozad, Gering, North Platte, Ogallala, Bassett, Long Pine, Valentine, and Gothenburg.

Archers are among the most divided, classified, and otherwise categoried of all sportsmen. Men and women are in separate divisions. These are further broken down into free style and instinctive categories. The free stylers use sights while the instinctive clan depend upon their eye, position, and experience to send their arrows into the gold.

Adults are further divided and classified according to their skills and their scores. The classifications are based on total points achieved on the targets. Youngsters breaking into the sport are classified by age. Kids 12 and under are cubs, juniors are 13 to 15, and intermediates are 16 to 18-year-olds. Once they're over 18 they take their chances with the adult dead-eyes.

Besides the weekly sessions, the feather pushers break up the practice routine with exhibitions and trick shooting. Candle snuffing, balloon breaking, cigarette splitting, and penetration demonstrations are among the more spectacular displays. Most clubs hold a midwinter instruction class which covers six weekly sessions. Fundamentals of holding, aiming, position, and release are stressed.

In Nebraska, the state indoor tournament is the big event of the winter season. For better than 12 hours some of the best bowmen in the state fire the various rounds. The tournament is a tough test of skill and stamina.

Current free-style champion is John Downer of Lincoln, while Doris Shaumann of Grand Island leads the ladies. Ernest Wolfe of Omaha is the champion instinctive shooter and Mae Lemond of Lincoln rules the women's division.

But there are plenty of newcomers from all over NEBRASKAland ready to challenge the champs. In the meantime, why don't you get in on this exciting indoor sport? Who knows? In a few years you might be the top bow-bender in the state.

THE END FEBRUARY, 1964 31

CAMPING ON WHEELS

Take the rough out of roughing it with a comfort-filled trailer by Lou EllUNLESS YOU'RE an experienced camper of long standing, establishing and living in a tent-type camp can prove frustrating and tedious. Hundreds of families in NEBRASKAland have not seen a fraction of the state's outdoor attractions or fished its best trout streams, simply because they can't bear the thought of "roughing it".

Several Nebraska manufacturers are changing that. They're building a variety of mobile camper units that eliminate the need of tent pitching or cooking over a smoky wood fire. There's one for the rugged hunter or fisherman who wants nothing more than a comfortable place to sleep. Others range through intermediate degrees of utility to one built for the traveling family whose most timid member demands all the comforts of home.

The makers realize that a mobile camping unit is a luxury item, used for a limited period during the year, and the rigs they build bear amazingly modest price tags. For instance, there's the Snyder Fiber Glass Sleeper, a shell-like cover designed to fit within the box of most pickup trucks.

"We've felt for a long time that hunters and fishermen need easily movable, inexpensive sleeping quarters," says Larry Snyder who, with his brother Mervin, designed and produce the unit.

Since a pickup truck is a natural to take sportsmen into the back country, they figured a shell to convert the pickup box into living space would be a natural. The shell would need to be rugged enough to withstand the knocks and jarrings of rough or nonexistant roads, and yet light enough to be installed quickly by one man.

Using a farm hayloft as work space, the brothers began experimenting with Fiberglas. They finally came up with a shell with crank-out windows for ventilation and a lift-up door at the back for easy entry.

32 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

The occasional user simply spreads sleeping pads on the floor of the pickup and does any cooking on a portable gas stove set on the lowered tail gate. The do-it-yourselfer can build in any convenience he may wish to add for more comfortable camping, giving him a custom-made rig. Prices on the Snyder Sleeper begin at $247.50.

For those who don't own a pickup, Holiday Industries of Omaha produce a family-sized camping trailer which will go anywhere a car will go. Their Porta Camper might be called a tent on wheels. Its basic design is a low, two-wheeled box trailer into which the bunks, cooking, and eating space is built. Headroom comes from collapsible canvas walls and a roof that raises into position in a few moments with very little effort.

The Holiday people build the interior of the camper pretty much to individual needs. While the bunks are standard, kitchen fixtures are up to the buyer. If you already own cooking gear that can be utilized, cost of outfitting the vacation rig can be kept to a most satisfactory level. For boaters, the Porta Camper offers an optional boat rack which fits on the top of the outfit when folded for traveling to fishing spots.

Champion Home Builders at York manufacture the Overnighter Camping Trailer. The unit is about as compact as a fully enclosed camper can be, with its interior practically filled with two double beds. A storage compartment under one of the bunks is accessible from either the outside or the inside of the trailer, facilitating rapid packing of gear. A small sink, with shelf space for a portable camp stove and storage for basic cooking utensils, is provided on a swing out entry door.

CAMPING ON WHEELS continuedThe Overnighter seems designed more for the hunting and fishing fraternity than for family camping, but it adapts to bigger groups through a special tent which attaches to one side of the outfit. This provides additional living space for extended stays in one location where there are more opportunities for comfort. The rig without the tent lists at $635.

Lincraft Industries of Lincoln had real comfort in mind when they designed the Lincraft Travel Trailer. It's built for the family who does considerable camping out and frequently moves from spot to spot. Four or five people will enjoy all the comforts of home in this traveler.

The trailer features a water tank and pump, city water hookup, a toilet with holding tank. The three-burner stove and oven, refrigerator, and interior illumination operates from a butane tank fastened to the trailer tongue. A butane wall heater is optional if you camp out during the winter. Winter camping is completely feasible, since the rig is well insuiated with Fiberglas and vented for proper ventilation. What is dining area during the day is taken up with fold-down beds at night. A full-sized wardrobe and plenty of storage cabinets are fitted into this amazingly compact home on wheels.

Lincraft trailers are assembled by a staff of six men who take £reat pride in their craftsmanship. The product is distributed over several Midwestern states to an ever-expanding list of satisfied owners. The basic price tag is $1,265.

Connie's Mobile Cabins of Chadron combines the

advantages of both a vacation trailer and summer

cabin. On the road, this eight-foot-wide rig has all

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the ease of portability found in a trailer. When you

get to your camping spot, it sets up to a 15 by 20-foot

cabin complete with sink, gas range and oven, and

light fixtures. It's fully-insulated throughout to boot.

the ease of portability found in a trailer. When you

get to your camping spot, it sets up to a 15 by 20-foot

cabin complete with sink, gas range and oven, and

light fixtures. It's fully-insulated throughout to boot.

The exterior is quarter-inch plywood with redwood finish. The price is kept down by leaving the interior finishing up to the buyer. Basic price is $1,995.

Don't let "camping out" keep you from hitting the open road. Somewhere in this line-up of Nebraska-made mobile camps, you'll likely find the very one that will fill your every need. With anyone of these homes on wheels, you'll live in comfort while you explore the NEBRASKAland trail.

THE END

BIG BASS

continued from page 15was paid to two small single-engine planes taxiing toward the fishing area. Clair Williams and John Brainard of Broken Bow unloaded from one plane and hurriedly began drilling holes. Bill Williams, brother of Clair, was piloting the other craft out of Broken Bow.

Roy Richards of Valentine, using a red and white spoon, had just filled his limit of 10 bass in a little less than an hour. The gals were getting in on the action, too. The wives of Bill and Andy Rhodes of Valentine were having the time of their lives.

It was shortly after I made my way to the west end of Hackberry and cut a couple holes that little Pat McGuire hooked the big pike. His dad, mother, and sister were all fishing, but the pike was the first strike for the family. A few minutes later, after a hasty repair of Pat's outfit, the four-year-old latched onto a 12-inch bass. I have a feeling he'll be a confirmed ice fisherman.

Seventy-five per cent of the bass were in the 12-to-14-inch class, the remainder a shade smaller. Some hit the scales at three pounds. Chuck Higgins of Valentine had such a lunker and I saw at least a half dozen more.

A fisherman just coming from shore waved to me and I saw it was Corky. We chatted about the fishing, as Corky sunk a couple of holes alongside. Both of us wondered how long fishing as hot as this would keep going. The Valentine tackle shop operator was using a level-wind casting reel on a short medium-action ice-fishing rig. He had lost a couple of pike in the 10-pound class with regular ice sticks before switching over to this outfit.

While lures are varied, there is a pre-dominance of the ''Swedish Pimple" artificial type, a heavy forged jigging spoon. Conventional spoons, lk ounce or less, spinners, and ice flies follow in order of popularity. The best colors are nickel, gold, red, and white for spoons. Yellow, brown, and black are tops in ice flies.

While fish may be taken on most any kind of a rig, successful Hackberry Lake fishermen recommend 8-to-10-pound test line. When no reel is attached, heavier line should be used. If you're fishing for bass, 6-pound-test is usually sufficient. The lighter the line, the better the action of the spoon is as it is jigged.

Corky carries an extra-light-action jigging rod loaded with 4-pound-test line for bluegill. Ice flies and tiny jigging spoons work best. Bass will often take the little lures and the four-pound test will bring in a good share of them.

My fishing partner landed four bass in quick order before they took an interlude from their feeding spree. Corky suggested that we hike back to the car and move westward down the shore. Almost a mile from the crowd, we parked and hiked out across the ice to a spot Corky figured looked productive. Within a short time he had filled his limit of bass and was jigging a tiny spoon for bluegills.

I didn't fill my bass limit, but by the time the sun had set I had iced eight big-mouthed beauties. They averaged about a pound apiece. In addition, a half-dozen bluegills hit the red and white spoon I was jigging.

Pelican, Duck, and Watts lakes are also good producers on the refuge. Corky says the bass in Pelican are a lot bigger than those on Hackberry. He had fished there the day before. Corky and a friend had landed 11 bass, with a good share of them better than two pounds.

Even veteran anglers would find

Hackberry's fantastic bass bonanza

hard to beat. I've never seen a large-mouth feeding spree to come anywhere

near this one. Perhaps it will never

happen again. But maybe it will. If

it does, I hope Corky spreads the word

so I can get in on the action.

hard to beat. I've never seen a large-mouth feeding spree to come anywhere

near this one. Perhaps it will never

happen again. But maybe it will. If

it does, I hope Corky spreads the word

so I can get in on the action.

COY DUCKS

continued from page 17hunting. Take it home and put it on the mantel for your friends to admire."

Although they never played a big part in history, cork decoys are of interest. They first were made by building up two layers of cork salvaged from life preservers found on beaches. Cork is too expensive to buy, but some decoys made of wood with an outer layer of cork are still popular.

Following the close of the Civil War, machines were made to turn out decoys on a mass production basis. Referred to as factory decoys, they were looked down upon by some, but were popular thoughout the Middle West. Their cost, $2,50 to $9 a dozen, was within the price of everyone. What they lacked in quality they made up for in quantity.

The decoy maker isn't bound by tradition. A number of odd-appearing fakes have been concocted by imaginative individuals with surprising results. Discarded auto tires cut into sections with a silhouette head are effective for bringing in wary geese. Nail kegs painted black do just as well.

FIBER GLASS-THE BEST "WEATHERER" AROUND! ER I--P \|^%^ Widely popular fiber glass sleeper/camper for pickup truck is lightweight, easy to clean, sleeps four. Rustproof, watertight, resistant to insect damage, extra sturdy construction. Perfect for fishing and hunting trips, vacations, camping—whenever you want to save on expensive motel/hotel bills . . . convenient carry-all for gear and equipment. • Rear and side awning windows • Good cross-ventilation • Lift-up door in rear (with lock) • Installs in just minutes! See illustration in last month's OUTDOOR NEBRASKA! WRITE FOR PRICES AND MODEL SPECS! ORDER NOW! FIBER GLASS COMPANY 3701 North 48th Lincoln, NebraskaShadow decoys, an oversized silhouette fastened upright on a large round board, are particularly good early in the morning and during snowstorms. The silhouette is painted black and the platform dull green.

Inflatable duck and goose latex decoys made in Nebraska are probably the most lifelike "foolers" available. Fiberglas, plastic, and styrofoam have come into the picture in recent years. Their lightness makes them ideal for pothole shooters who move from one place to another in the course of a day. Their only disadvantage is that some are made by persons who, unfortunately, don't know a teal from a Canada goose.

Decoys have come a long way from the first crude model woven from reeds. But whether made from reeds or latex, they have done their job well, and in the process, provided hunters with one of the most exciting sports ever known to man.

THE ENDDEER PATROL

continued from page 11areas after the fall hunting seasons than before. The experts believe the animals undergo certain subtle changes in behavior during the winter months. They also point out that visibility is usually better late in the year.

If you have any plans to do your own spotlight survey, don't. Carl Gettmann, chief of law enforcement for the Game Commission, has this to say about spotlighting.

"It is unlawful for anyone to take or attempt to take any game bird or animal with the aid of a spotlight or any other artificial light. If our officers find anyone spotlighting in an area where game abounds they will naturally investigate. Unauthorized spotlighting on private land is trespass and the violator may be prosecuted if the landowner desires to do so. Also, hunters will actually harm themselves by spotlighting deer. If the practice is excessive, the deer will be spooked out of the area, the researchers will not be able to conduct their surveys, and the deer hunting improvement program will be hampered."

Besides the information gathered, the surveyors get an excellent picture of the area's mammal population. During the treks, watchers see coyotes, badgers, skunks, porcupines, jack rabbits, kangaroo rats, and many other nocturnal prowlers. From time to time, they have the opportunity to observe the little dramas of nature that would otherwise go unnoticed. They lose some sleep but there's compensation, too. When the seasons open they know right where to go to get their deer, sometimes.

THE END

Where to go .. . PIONEERS PARK

Trail rides and ponderosa join with golf and historical monuments in this close-to-Lincoln fun spotPIONEERS PARK is for people, a place where children romp and play to their heart's content while adults unwind from the pressures of the day. Only 15 minutes from downtown Lincoln, the 600-acre retreat seems as remote from the hustle and turmoil of the city as any rural spot in Nebraska.

Here lakes, trees, and lush meadows are dedicated to the use and enjoyment of resident and tourist alike. Located on the rolling prairie, the park is a skillful blend of man's development and nature's original handiwork. Open the year around, the park is free to all comers.

Highly developed with an 18-hole golf course, playgrounds, picnic areas, lakes, amphitheater, and bridle paths, Pioneers Park still retains much of the charm and simplicity of the prairie from which it came. A network of roads and trails lead visitors to practically every attraction with a minimum of walking.

A number of show pastures, hosting native and exotic grazing animals, make it a children's delight. Slides, swings, merry-go-rounds, giant steps, and teeter-totters are available to drain off their energies.

Visitors entering the park are greeted by the formal landscaping of Harris Circle, surrounding the life-sized bronze statue of a buffalo. The circle is named for Mr. and Mrs. John F. Harris who donated 500 acres to Lincoln for development as a city park. Later, they donated another 100 acres to bring the park to its present size. They also commissioned the bronze of the buffalo.

Development of the tract as a city

park gained its impetus during the

38

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

depression. Tree planting, landscaping,

lake development, and other projects

were carried out under the federal

WPA program and other related agencies during the 1930's.

depression. Tree planting, landscaping,

lake development, and other projects

were carried out under the federal

WPA program and other related agencies during the 1930's.

From time to time, other improvements were made. The Smoke Signal, a huge statue of an Indian using the smoldering fire and blanket to signal his tribe to the westward, was erected in 1935. The statue is a likeness of Chief Red Cloud.

After World War II, Pine Bowl was developed and dedicated. The natural amphitheater was built by public contributions and dedicated to the veterans of World War II. It seats 3,000 people and offers standing room to another 7,000. Pine Bowl features numerous concerts and other activities during the summer months.

Every summer weekend, railroad buffs and small boys flock to "Old 710", a giant steam locomotive of another era. The big engine is a gift from the Burlington Railroad.

Pioneers Park is the United Nations of animaldom. Zebus from India share the same pasture with the cranky Texas longhorn while stolid buffalo and tiny Mexican burros graze over the same slope in studied indifference to each other. Deer from Japan and western Nebraska thrust moist noses through the fences for handouts.

Elk from the Rockies, llamas from South America, and water buffalo from Asia trade silent comments about the people who watch them, while Shetland ponies and mouflon sheep share shelter in the rolling pastures behind the high wire fences. Most of the animals have lost their inherent fear of man.

Waterfowl of practically every description are found on the little lakes that dot the park. Some of the geese and ducks are captives. Others drop in to visit during their annual migrations.

The buffalo, longhorns, and elk are real tourist attractions, the first that many visitors from the East have seen. These animals, the old engine, and Red Cloud, make Pioneers a natural for the vacationer out to discover the West.

Pioneers Park is an old park. Its development is finished and now its problems are largely those of maintenance and protection, but as long as kids yell, "Here deer, deer," as they thrust bread through the fences, or girls swing high, and young lovers stroll along the trails, Pioneers Park will remain young, as young as its givers and builders intended that it should.

THE END FEBRUARY, 1964 39 CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

MISCELLANEOUS

15 cents a word: minimum order $3

April closing date, March 1

DOGS

AMERICAN WATER SPANIELS: Fine hunters, retrievers.

Choice puppies. AKC registered. John Scofield, Jonesburg, Missouri.

FOR SALE: Vizsla dogs. All ages, championship ancestry. F.D.S.B. and A.K.C. registered.

Wayne Hoskins, Enders, Nebraska. Telephone:

Imperial TA 3-4858.

KEWANEE RETRIEVERS: Black Labradors

exclusively. Our fine breeding is paying off.

Excellent conformation and ability are pushing our dogs into field and show work.

State age, sex, and price desired; or call

26W3, Valentine, Nebraska.

BRITTANY SPANIEL PUPS, vaccinated and

ready to go. Rudy Brunkhorst, Telephone

563-0011, Columbus, Nebraska.

GUNS

NEW, USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS

Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca,

Colt, Ruger, and many others in stock. Buy,

sell, or trade. Write us or stop in. Also live

bait. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, just off U.S.

136, Fairbury, Nebraska.

NEW, 20-PAGE CATALOG contains pictures,

specifications and prices of Marlin guns for

1964. Thirty-five different models of rifles and

shotguns in all . . . at prices ranging from

$17.95 to $126.95. This comprehensive catalog

gives you all the information needed to select

the best gun for anybody . . . young or old

. . . novice or marksman . . . target-shooter

or big game hunter. You'll also learn why

America's finest marksmen and huntsmen

agree . . "you pay less . . . and get more

from a Marlin." Bonus: Copy of the Bill of

Rights, guaranteeing Americans the right to

keep and bear arms, printed on parchment

paper and suitable for framing included free

with every catalog. Write Department 265,

The Marlin Firearms Company, New Haven 2,

Connecticut, U.S.A.

SMOKE FISH, GAME. Build inexpensive electric smoker. Instructions, drawing, recipes.

$1. Make summer sausage, salami, jerky from

game. Instructions, recipes. $L Oldtimer

John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840.

TRAP NIGHTCRAWLERS, earthworms by

thousands. Instructions, drawing, $1. Old-timer John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840.

SLEEPING BAGS, 100 styles, tent-camping

equipment specialist. Send 25f for 96 page

catalog. Morsan, 810-Y, Route 17, Paramus,

New Jersey.

"SONG OF NEBRASKA" place mats for individuals, clubs, Chambers of Commerce, restaurants, motels.

Available now. Artistically designed exclusively for Nebraska on finest

white homespun paper. Suitable for any

decor. Includes games and puzzles for children and adults. Quantity rates, Mrs. Ann

Hamley Petersen, Battle Creek, Nebraska.

EARN $2.50 HOUR assembling our small lures

and flies for stores. Easy to do. Write:

Snatch-All, Ft. Walton Beach 13, Florida.

FOR SALE: Concessions—Swanson Lake,

Trenton, Nebraska. Cafe and building, boats,

motors, bait set up, gas and oil, house, trailer

house and area, and other related equipment.

Roy Dauble, 2665 South Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. Telephone 423-8429.

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

They meet in

OUTDOOR Nebraska's

Classified Pages

Only OUTDOOR Nebraska offers you a

state-wide active, buying audience.

More than 27,000 OUTDOOR Nebraska's

readers make your ad work overtime.

At 15 cents per word, $3 minimum, it is

the most economical way to advertise yet.

For Fast Results Use

OUTDOOR Nebraska's Classified Page

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

MISCELLANEOUS

15 cents a word: minimum order $3

April closing date, March 1

DOGS

AMERICAN WATER SPANIELS: Fine hunters, retrievers.

Choice puppies. AKC registered. John Scofield, Jonesburg, Missouri.

FOR SALE: Vizsla dogs. All ages, championship ancestry. F.D.S.B. and A.K.C. registered.

Wayne Hoskins, Enders, Nebraska. Telephone:

Imperial TA 3-4858.

KEWANEE RETRIEVERS: Black Labradors

exclusively. Our fine breeding is paying off.

Excellent conformation and ability are pushing our dogs into field and show work.

State age, sex, and price desired; or call

26W3, Valentine, Nebraska.

BRITTANY SPANIEL PUPS, vaccinated and

ready to go. Rudy Brunkhorst, Telephone

563-0011, Columbus, Nebraska.

GUNS

NEW, USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS

Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca,

Colt, Ruger, and many others in stock. Buy,

sell, or trade. Write us or stop in. Also live

bait. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, just off U.S.

136, Fairbury, Nebraska.

NEW, 20-PAGE CATALOG contains pictures,

specifications and prices of Marlin guns for

1964. Thirty-five different models of rifles and

shotguns in all . . . at prices ranging from

$17.95 to $126.95. This comprehensive catalog

gives you all the information needed to select

the best gun for anybody . . . young or old

. . . novice or marksman . . . target-shooter

or big game hunter. You'll also learn why

America's finest marksmen and huntsmen

agree . . "you pay less . . . and get more

from a Marlin." Bonus: Copy of the Bill of

Rights, guaranteeing Americans the right to

keep and bear arms, printed on parchment

paper and suitable for framing included free

with every catalog. Write Department 265,

The Marlin Firearms Company, New Haven 2,

Connecticut, U.S.A.

SMOKE FISH, GAME. Build inexpensive electric smoker. Instructions, drawing, recipes.

$1. Make summer sausage, salami, jerky from

game. Instructions, recipes. $L Oldtimer

John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840.

TRAP NIGHTCRAWLERS, earthworms by

thousands. Instructions, drawing, $1. Old-timer John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840.

SLEEPING BAGS, 100 styles, tent-camping

equipment specialist. Send 25f for 96 page

catalog. Morsan, 810-Y, Route 17, Paramus,

New Jersey.

"SONG OF NEBRASKA" place mats for individuals, clubs, Chambers of Commerce, restaurants, motels.

Available now. Artistically designed exclusively for Nebraska on finest

white homespun paper. Suitable for any

decor. Includes games and puzzles for children and adults. Quantity rates, Mrs. Ann

Hamley Petersen, Battle Creek, Nebraska.

EARN $2.50 HOUR assembling our small lures

and flies for stores. Easy to do. Write:

Snatch-All, Ft. Walton Beach 13, Florida.

FOR SALE: Concessions—Swanson Lake,

Trenton, Nebraska. Cafe and building, boats,

motors, bait set up, gas and oil, house, trailer

house and area, and other related equipment.

Roy Dauble, 2665 South Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. Telephone 423-8429.

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

FOR

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

SALE

They meet in

OUTDOOR Nebraska's

Classified Pages

Only OUTDOOR Nebraska offers you a

state-wide active, buying audience.

More than 27,000 OUTDOOR Nebraska's

readers make your ad work overtime.

At 15 cents per word, $3 minimum, it is

the most economical way to advertise yet.

For Fast Results Use

OUTDOOR Nebraska's Classified Page

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

WANTED

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

TO BUY

MARI SANDOZ

(continued from page 9)either time was the skin more than scratched. My father whipped me for writing when I was around 10, but what's one whipping more or less? I went right on writing, under pen names, many of them, until Jules discovered about it once more.

"He couldn't whip me then—I was over 400 miles away—but he wrote me a one-sentence letter: 'You know I consider artists and writers the maggots of society,' and signed it—Jules A. Sandoz."

As a writer, she had, and has, a great story to tell about the change from the Old West to the new that took place before her eyes. "Perhaps my father's objections really helped me," she mused, "I know they only made me more determined to write."

On August 23, 1954, the state that she still calls home, though she lives in New York City, recognized this brilliant native daughter. Governor Robert B. Crosby proclaimed that date as Mari Sandoz Day in Nebraska.

Mari Sandoz inhabits her works with the people she knew as a child at the Running Water, both the weak and the strong. She paints a picture with words of the land and those who conquered it (but not completely). Of the characters about which she writes, Mari Sandoz, too, must take her place among the strong and the builders.

THE END 40

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

Have Friend, Will TravelPENNSYLVANIA ... A fawn deer raised as a pet on a farm decided to return to the mountains where it belonged. The odd twist is that the deer took its friend along, the farmer's six-month-old beagle.

Underwater ComfortWASHINGTON ... The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service has recently added a two-man submarine to its management tools. The submarine will permit biologists to conduct fisheries research for extended periods and without fear of marauding sharks.

Conscience MoneyPENNSYLVANIA ... A game protector tells the tale of a hunter who "got religion" and wanted to atone for his sins. Thirty years ago, the hunter had illegally shot a deer and now wanted to clear his conscience by paying the fine. Though told the act was outside the statute of limitations, the hunter insisted on paying the $100 penalty. Then, with a guilt-free conscience, he went on his way.

IOWA . . . An Iowa fisherman followed a truck from the federal trout hatchery for miles, hoping to spot its destination. It finally stopped—at an airport where the fish were loaded aboard a transport.

Same For AllCONNECTICUT ... A recently passed law in the state legislature has eliminated nonresident hunting and fishing permits. Under the new law residents and nonresidents pay the same fee for permits.

What Price Insecticides?MISSISSIPPI ... A herd of Hereford cattle went into convulsions and died soon after being sprayed with what was apparently the wrong insecticide. Police said 180 cows perished and the manager of the farm was hospitalized in critical condition. Value of the lost herd was $40,000.

Inflatable DamPENNSYLVANIA . . . Designs for a $750,000 collapsible rubber dam to be installed on the Susquehanna River are nearing completion. The dam, eight feet high and 2,000 feet wide, will be formed by inflating a giant nylon bag coated with neoprene synthetic rubber. It can be installed at a far less cost than a concrete dam, and can be deflated to permit unobstructed runoff.

Howard Hoyle had a heart attack. But here he is, back on the job with his grandson, Tommy.

Most heart attack victims survive first attacks. Three out of 4 go back to work because your Heart Fund gifts, invested in research, have helped to produce life-saving advances in treatment and rehabilitation.

But many cardiacs are not so lucky as Howard Hoyle. Some 500,000 Americans still die each year of heart attack. The best way to fight this Number 1 killer is to give more to the Heart Fund for increased research, education and community service.

More will LIVE the more you GIVE.. HEART FUND

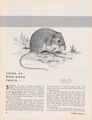

notes o n Nebraska fauna...

POCKET MOUSE

SLEEPING BY DAY, working feverishly at night is the life pattern of the smallest rodent in North America, the pocket mouse. This little known and seldom seen mammal is a member of the Heteromyidae family. Though among the most interesting creatures on the continent, little is known of the pocket mouse because of his shyness and nocturnal traits.

There are 20 species, all limited to the western half of North America. None have ever been seen east of the Mississippi River. Primarily creatures of the hot dry deserts of the southwest, varieties of the pocket mouse are found from British Columbia in the north to the sweltering valleys of Mexico in the south. Well adapted to their environment, they have the ability to survive without water. The sandy soil of their preferred range fosters their burrowing instincts.

Four varieties of pocket mice are found in Nebraska. The tiny Wyoming and Silky pocket mice live in the western half of the state. The Plains and Hispid varieties range throughout the state. The Wyoming, Plains, and Silky are all similar in appearance. Soft fur and light weight are their common characteristics. The three bantamweight members of the Nebraska group average slightly more than % ounce each. They can be distinguished by their coloration.

An olive gray coat identifies the Wyoming member of the clan.

He has pale yellow spots on his ears

42

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

and a yellowish wash along his sides. He is sometimes called the olive-backed pocket mouse because

of his distinctive coloration. The Silky and Plains

are a pale yellow, but the Silky has a spattering of

black hairs on the upper portion of the body and has

a distinct yellow patch behind each ear.

and a yellowish wash along his sides. He is sometimes called the olive-backed pocket mouse because

of his distinctive coloration. The Silky and Plains

are a pale yellow, but the Silky has a spattering of

black hairs on the upper portion of the body and has

a distinct yellow patch behind each ear.

Heavyweight of the clan is the Hispid. His coat is mixed with stiff, flattened spines which give him some protection against thorns and insects. His size is also a distinguishing characteristic. He averages about eight inches in length, while his smaller cousins seldom exceed 3 3/4 inches. The long tails of each make up as much or slightly more than half of his total length.

All pocket mice can be easily identified by inspecting their front incisors. All have a vertical groove in the front teeth. In the smaller species, a magnifying glass is needed to see the unusual groove, but it is there. Its purpose is unknown.

Energetic burrowers, pocket mice live in tunnels that may extend in a straight line with a grass-lined nest at the end. But the burrow can be more elaborate with several branches extending to store-rooms and nesting areas. Tunnels may be as long as seven feet. The pocket mice store up food, mostly seeds, for lean periods. During cold weather they may be semidormant but they are not true hibernators.

These interesting little rodents evade their enemies and avoid summer's scorching heat by always plugging up their burrow entrances after a night's foray for food. Entrances are usually beside rocks and shrubbery and go down at a sharp angle. In the desert blowing sand helps to obliterate entrances and blot out tracks.

Somewhat gregarious in habit, the pocket mouse communicates in a high-pitched squeak. Favored spots may be honeycombed with a number of burrows with all inhabitants leading a peaceful coexistence. However, the little rodents do not form colonies and the mouse actually leads a rather solitary life except during mating.