OUTDOOR Nebraska

January 1964 25 cents LAST-MINUTE HONKER Platte River Special SOLO PHEASANTS Hunting Alone Is For The Birds BEATING THE WHITE DEATH Blizzard Ride Out WINTER'S FOR TROUT

OUTDOOR Nebraska

Selling Nebraska is your business January 1964 Vol. 42, No. 1 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor J. GREG SMITH, Managing Editor Bob Morris, Fred Nelson PHOTOGRAPHY: Gene Hornbeck, Lou Ell ART: C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, Frank Holub ADVERTISING MANAGER: Jay Azimzadeh

BEATING THE WHITE DEATH

Your life's the jackpot when storms play their deadly gameBLIZZARD IS A dread word on the Great Plains. Each winter, severe storms, accompanied by heavy snow, high "winds, and mimbing cold, swirl out of the 'tectic and sweep across America's heartland, leaving a suffering and death in their wake. Chief victims of these storms are motorists who are caught on the road and abandon their stalled cars to seek sheltef on foot. Confused by the frightening fury of thelstorm and tormented by the vicious wind, they wHnder in circles until exhausted. Then the cold gets in its deadly work. Days later, rescuers find their bodies. Some are only yards from shelter; others, miles from their starting points.

Nebraska has seen its full share of these tragedies.

Two great storms of recent history, the blizzards of

January, 1949, and March, 1959, claimed a number

of lives in the western part of the state. Among them

were motorists who abandoned their cars in a vain

attempt to reach shelter. Many would be alive today

if they had stayed in their cars and waited out the

storm. A few precautions and a minimum of survival

JANUARY, 1964

equipment would have increased their chances a

hundredfold.

equipment would have increased their chances a

hundredfold.

Extra clothing or blankets, a shovel, some food, and common sense will see the traveler through the ordeal. Unfortunately, only a few have foresight to provide basic survival necessities before they tackle a winter trip. In 1949, many travelers withstood 72 hours of the punishing storm and emerged none the worse for the experience. Others left their cars and perished.

But some of those who stayed in their cars forgot the insidiousness of carbon monoxide. Searchers found them dead in their automobiles, the key on, the gas tank empty. It was easy to reconstruct the story. The driver kept the motor running for the heater. Drifting snow clogged the exhaust, backed up the deadly fumes and spread them through the car.

When stranded in a blizzard, you face three major problems. You must keep warm enough to sustain life, have enough food to keep your body's heat and energy at functional levels, and arrange for adequate ventilation since packing snow will shut off the oxygen supply. Water is no problem since snow can be eaten without harmful effects.

A basic survival kit can be assembled with little

expense. Its value in times of emergency cannot be

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

overestimated. Extra clothing for each occupant,

blankets or sleeping bags, some dry and nonfreezing

foods, candles, a sharp knife, and kitchen matches

should be included in the kit. Just as important are

a shovel and sturdy tow chain. A flashlight and extra

batteries should be stored in the glove compartment.

overestimated. Extra clothing for each occupant,

blankets or sleeping bags, some dry and nonfreezing

foods, candles, a sharp knife, and kitchen matches

should be included in the kit. Just as important are

a shovel and sturdy tow chain. A flashlight and extra

batteries should be stored in the glove compartment.

Everything can be stowed in the trunk of a car or under the seats and around the spare tire well in a station wagon. A round-pointed shovel is better for emergency use than the wide-bladed snow shovel. The handle can be shortened if necessary.

The amount of food should be based on three pounds per day per person for a maximum of three days. Few blizzards last more than 72 hours without a lull. Even the vicious 1949 blizzard had lulls and recesses which allowed rescue operations.

Dry cereals, cookies, crackers, and hard candy are excellent emergency rations. Dried apricots or apples are also good additions. Some canned meats and sausages are suitable, but avoid foods that spoil quickly or are so watery that they freeze.

You'll need your normal food intake, even though cooped up in a car with little to do. The cold and nervous tension will drain energies almost as fast as hard physical labor. The body needs carbohydrates to produce heat enough to overcome the outside cold. Avoid alcohol. Its warming qualities are grossly exaggerated and its dulling of reason and judgment may be just enough to tip the delicate balance of life and death.

If possible, back your car against the storm so the wind and snow strike the trunk. The lid, the dead air space, and the back seat cushion are excellent insulators against the creeping cold. The sloping surface deflects snow and minimizes drifting to a degree.

The sealing action of the snow presents ventilation problems, and this is where your shovel will earn its passage. Try to keep at least one window clear. Over several hours, drifts will completely bury an automobile. Use a shovel to dig vertically up from the window, rather than horizontally or down to the bottom of the door. Snow will drift for several feet in a horizontal direction but seldom gets very deep in the immediate vicinity of the car.

Keeping the motor running for the heater is tempting but dangerous. In time, the car will run out of gas and the heater becomes useless. Unless the exhaust pipe is cleared at frequent intervals, carbon monoxide will get in its fatal licks. Napping with the motor running is a quick one-way ticket to eternity.

Layers of clothing trap body heat and ward off the creeping cold. Ears, (continued on page 40)

JANUARY, 1964 5

SOLO PHEASANTS

by Bob Morris Hunting alone has it all over "gang-like" tactics in my bookTHE NORTH wind rolled across the naked fields, pushing the fluffy top covering of snow ahead like a wave. Working the lee side of the hedge provided some protection, but the icy December blasts still whistled past my ears and cut into my face and hands like a knife.

My eyes were glued ahead waiting for the movement that would mean a pheasant had picked the hedge as a refuge from the coming storm. About 60 yards ahead two hens and a rooster galloped out of the cover, high stepping their way from danger. If three came out there was a good chance more were around. The distance to the end narrowed under my steady pace. Finally another rooster climbed the sky, cackling his displeasure at being disturbed.

The 12-gauge boomed and the bird fell, his protest still reverberating through the icy stillness. The dog didn't wait for my command but was off in a flash. The snow crunched under his feet as he raced over to the fallen ringneck. With a quick lunge, he grabbed the bird firmly in his mouth and made his way back, his tail wagging with pleasure.

We rested by the hedge row a few minutes before heading for the car. The bird, my third for the day, felt comfortable bouncing along behind in the game jacket. By the time I reached the car, the late afternoon sun was opaque, hidden behind the milky sky. The wind began to die down but still made its presence felt. It was only a short five-minute drive back to Harvev Townsend's farm and the warmth of his home.

Pulling into the yard, I hurried over to the pump, gutted the birds and washed them out under the freezing water. Hanging the pheasants head-up to drain, I walked to the house where Harvey was waiting for me.

"Get in here before you freeze," he ordered, fighting the wind to keep the door open.

The hot water felt like a million needles as it

ran over my hands in the sink. I could feel the blood

JANUARY, 1964

7

surging back into them as I rubbed the towel briskly

across my fingers.

surging back into them as I rubbed the towel briskly

across my fingers.

"Do you have time for a cup of coffee?" Virginia asked. The question was rather pointless as the cup was half full before Harvey's wife asked. Wrapping my hands around the thick, steaming cup seemed to warm my whole body. We talked for a while—the upcoming Orange Bowl game, the threatening storm. The warm room and conversation were relaxing. Their son, Dick, came in from milking, stamping his feet, but carefully holding the pail so it wouldn't spill.

"If it gets any colder, Trixie will be giving ice cream instead of milk," he muttered as he walked into the kitchen.

Soon it was time to leave. The dog nestled close, his golden coat like a warm blanket. Patting his head, I remarked on the icy road ahead. All I got for my effort was a sigh as he settled down to sleep. Undismayed, I kept on.

"Well, we had a pretty good day. We saw seven roosters and got three, and here it is, the middle of December when all the pheasants are supposed to be gone."

The dog began to snore. He's pretty good on pheasants but not much of a conversationalist. I'd been hunting with him since the second week of the season. This made the seventh Saturday we hunted on and around the Townsend farm. In spite of popular theories, we seemed to see more birds each week.

The bulk of Nebraska's million-plus pheasant harvest is taken in the first 10 days. After that, the kill drops off drastically. There are still plenty of birds but few sportsmen to take them. That's when I really enjoy hunting.

When out by myself I have many advantages over the group-hunter. I don't depend on anyone's alarm clock but my own. When a bird gets up I don't have to worry where my companions are before shooting. If I should decide on a change of direction when half way through a field there's no concern about being yelled at by the drill sergeant each hunting group seems to attract.

In short, I'm my own boss. I hunt where, how,

and when I want. On one place I hunt, my friend

planted some popcorn along the edge of a field. He

told me about it and invited me to help myself. My

thoughts were on the corn, not pheasants, as I moved

into the field. While stuffing the ears into my game

8

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

pocket, a rooster broke out of a small patch of cover.

It took a few seconds to get untangled but I managed

to drop the bird. That day I came home with two

pheasants and nearly a bushel of popcorn.

pocket, a rooster broke out of a small patch of cover.

It took a few seconds to get untangled but I managed

to drop the bird. That day I came home with two

pheasants and nearly a bushel of popcorn.

There are disadvantages, of course, to hunting by yourself. Large corn and milo fields look like impossible obstacle courses for the solo hunter. But by following an erratic, twisting pattern through these fields you can often come up with good shots. Just as importantly, watch for pheasants flying out of the field toward smaller patches of cover. Mark where the birds land. Ringnecks have a reputation for running, but in my experience I have almost invariably found them within 10 feet or so from where they land under these conditions.

Another trick is to stop every few minutes and wait another minute before moving again. Any birds within range will generally panic before the minute is over.

Large shelter belts are the toughest for a lone hunter. If you go down through the middle, the pheasants fly out the sides. Work one side and they always seem to fly out the other. By working your dog down the center and staying about 20 yards off to the side you get better shooting. If nothing else, the birds will be driven out into patches of cover where a single hunter has a good chance of getting them.

Fence and hedge rows and small patches of cover are where the single hunter has it all over a group. These areas may not look like much but a pheasant is much shorter than you and needs less than a foot of cover to protect him from the wind and snow. Take your time walking this type of cover. A pheasant isn't inclined to run if he isn't pushed too fast.

Grassed waterways, draws, and silted up farm ponds are other excellent choices. In short, any small cover close to food and water is where pheasants hang out and singleton hunters can get good shooting. Regardless of the area you hunt, always work the birds toward water, road, or plowed field where they will be forced to fly.

Hunting solo is lonely, but if I want conversation there is always the dog. No matter the subject, he has never disagreed with me yet. I get my share of birds, hunting the way I enjoy most.

The next time you want to go out and all your friends are busy, take on the pheasants solo.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 9

THE REGAL HUN

THERE HAS never been a product advertised as second best. This holds true whether you're in the market for a detergent, new car, or hunting dog. Talk to the average dog owner and you'll find nothing but praise for his choice and seldom anything good about another breed.

There are two reasons for this attitude. First, no man is going to admit he made a bad choice. As important, the man who is enthusiastic about his dog generally made his selection on the basis of his hunting preference. The duck hunter eliminates anything but a retriever from his final selection. For pheasants, a breed that points the bird or flushes it within range is paramount. Flushing birds a mile away is worthless. To be of any value the dog has to hold staunch.

In states such as Nebraska, where a variety of game is abundant, an all-around dog is often the best bet. This is where the vizsla fits in. This Hungarian import is at least as good as most on pheasants and quail. At the same time, he can fill the bill effectively on waterfowl shooting on ponds and rivers.

This isn't meant to imply the vizsla is a cure-all for the dogless hunter and that this handsome aristocrat will out-perform other breeds. He's primarily a pointer and as such, does his best on upland game. As a retriever the vizsla's short hair is a disadvantage when it comes to taking a hard day out in the duck blind. Although he'll do a fair job under these conditions, a retriever would undoubtedly be a much better choice.

The vizsla is one of the newest hunting breeds in the United States, but his fanciers trace his history back to 10th century Hungary. Ancient stone etchings depict Magyar tribesmen hunting with a falcon and a dog with the dog bearing a strong resemblance to the modern vizsla.

Little information is available on the dog's development.

It's believed that as nets and firearms replaced falcons as a means of hunting, dogs with

10

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

pointing instincts evolved. Although many fanciers

say the Hungarian is related to the Weimaraner and

German short hair, records indicate the present-day

vizsla was established earlier.

pointing instincts evolved. Although many fanciers

say the Hungarian is related to the Weimaraner and

German short hair, records indicate the present-day

vizsla was established earlier.

Vizsla ownership was restricted to the nobility in Hungary until after the first World War and rigid breed standards were maintained. The only imports were to royalty in nearby countries. This kept the number of dogs at a low number and restricted their popularity in other lands.

In 1916 Hungarian breeders became alarmed at the deterioration of the vizsla through cross breeding, particularly with the English pointer, and a concerted effort was made to find true-to-line vizslas to re-establish the breed. This was accomplished during the 1920's and 1930's. Hungarians who fled the Russian occupation brought vizslas to the outside world.

This hunter's most distinctive feature is his gold-red or cinnamon coat, making him one of the most striking canines in the hunting class. The dog is lean with a regal bearing, accented by a docked tail. Average height is from 21 to 24 inches at the shoulder and weight ranges from 35 to 55 pounds.

As a hunter the vizsla is ideally suited for Nebraska and other Great Plains states where the terrain is similar to his home land. Perhaps for this reathe dog first became popular in the Midwest. Until recently, the largest number of registrations was found in Nebraska.

The regal canine has readily adapted to his new home and has no trouble with pheasants, grouse, and quail. He's similar to the German short-hair in range and speed, although some of the imports have scored high in field trials with pointers. These high-stepping individuals are a rarity, however, and the hunter looking for a speed merchant would do well to pass up the Hungarian.

Opponents claim the dog's deliberate manner is a fault, but in game-rich Nebraska the vizsla's thorough style of hunting is an advantage. He may let a few runners escape, but seldom will a bird that is sitting tight escape his sensitive nose.

Carl Wolfe, research biologist with the Game, Forestation and Parks Commission and president of the Nebraska Vizsla Club, uses his two-year-old female, Amber, during his pheasant research projects. She points nesting hens, newly-hatched chicks, and birds beneath 14 inches of snow. Wolfe says his dog even points single eggs laid indiscrimnately by hens before formal nesting begins.

The vizsla's exceptional nose and strong retrieving instinct is among his top qualifications. This cuts down on the number of cripples and dead birds that are lost, putting more meat in the pot. Unlike some pointers, the dog comes by his retrieving ability naturally and little work is required on this important phase of training.

Although the Hungarian isn't timid, he has a gentle disposition. This makes training either difficult or easy, depending on the handler. Sportsmen who are used to strong-willed breeds could easily have trouble if they use strong-arm tactics. A firm hand is necessary to properly train the dog, but kindness is the key to bringing out his best qualities.

For hunters with a limited amount of space, the vizsla makes a good house dog, and, in fact, the breed's boosters claim he "deserves" a place in the home. This riles those who feel a dog's place is in a kennel, but is fine for the average owner.

Vizslas have had some success in field trials in competition with pointers and setters, considering the few entered in all-breed events. But speed afoot isn't one of the Hungarian's strong points and he probably will never seriously challange other breeds in trials where ranging ability is a major factor.

Speed and range are two important qualities in a field-trial dog. The vizsla will never make his mark as an outstanding competitor, but for a gun dog he has everything the hunter needs. If you want a dog that works diligently on upland game, is outstanding at retrieving, and is an excellent companion, the vizsla fits the bill.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 11

CLEAN-UP CREW No. 2

Highways are meal tickets for this band of gourmandsWHY DOES a chicken cross the road? No one really knows for sure, but one fact is certain, many of those who begin the fateful trip, be they barnyard foul or wild animal, never live to see the other side.

Each year highways account for a large toll of

Nebraska's wildlife. Pheasants, quail, grouse, deer,

cottontails, squirrels, and even song birds are clobbered.

Their carcasses accumulate along state

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

roadways, and if it wasn't for nature's vacuum sweepers their remains would be a major litter problem.

roadways, and if it wasn't for nature's vacuum sweepers their remains would be a major litter problem.

In addition to killing wildlife, motorists also deposit paper, tin cans, and other items. Rubber from retread tires comes off, adding to the tide. The Highway Department spends around $60,000 a year cleaning the major roads in the state. Except for the efficiency of scavengers, the cost of removing wildlife could raise the price even higher.

Two maintenance crews patrol Interstate 80 from Omaha to Milford picking up litter and dead wildlife. During one six-month period 289 species of wildlife were removed from this 60-mile stretch. Everything from deer down to field mice is found along the roadway. Summer months are the deadliest when traffic is heaviest. Most kills come during the period before dawn, when nocturnal animals are returning from a night of feeding and aren't as wary as usual.

Disposing of the dead carcasses is accomplished by a host of undiscerning gourmands. The crow is one of the more familiar scavengers seen along the roadways. He and his clan are often observed in groups of two or more feasting on a mangled rabbit or pheasant. If they happen to be dining when a vehicle approaches, they leave their repast at the last minute and return as soon as the motorist has passed the scene. If one of them fails to leave in time to avoid being struck by a vehicle, he simply adds variety to the diet for the remaining members of the group.

Other volunteers included in this cleanup detail are certain species of hawks and owls, coyotes, skunks, raccoons, foxes, ferral cats and dogs, ground squirrels, opossums, magpies, and even insects and larva. If the dead animals are small enough, they are often dragged or carried back from the road where they can be fed on at leisure. This explains why some animals are seldom seen feeding along the roadside.

Some free loaders prefer their food aged. This is especially true of the turkey vulture which visits Nebraska during migration periods. He seldom takes on anything unless it has been dead for several days or even weeks. Special adaptations such as a bare head and a powerful beak allow him to dip into a carcass and tear off the flesh without having his repast clutter up head feathers.

The coyote employs the motto, "call thou nothing unclean." His food habits are such that anything fresh or decayed, hot or cold, cooked or uncooked is good enough to eat. Any birds or animals killed on the roads constitute a likely candidate for his next meal.

This makes a food habit's study whereby blame or credit is assigned to the coyote extremely difficult to evaluate. There is a great deal of difficulty in identifying the wide variety of different items that are eaten. Also it is practically impossible to determine whether the food item was caught alive or eaten as carrion. The coyote, like other animals in the predator group, is neither all good nor all bad but a combination of both.

Many a camper on the plains has gone out following an overnight stop to find his horse gone, the rope

chewed off by a coyote. Cow hides that have been

dried out on the prairie will be chewed on for years

afterward. Snakes are often killed and eaten. The

coyote's special adaptation seems to lie in the fact

that he possesses a high level of intelligence, has a

JANUARY, 1964

13

keen sense of sight, smell, and hearing, and exhibits

a digestive system that accept anything that is

ingested.

keen sense of sight, smell, and hearing, and exhibits

a digestive system that accept anything that is

ingested.

Other scavengers such as skunks and opossums also make use of whatever food item is the most readily available. Their diet will vary with the time of year and the abundance or scarcity of various foods. During the summer months when insects are the most numerous, grasshoppers and crickets occupy a prominent position. In the fall, the scavengers may shift their attention to fruits and berries, and in the winter rodents become more important. But none of the cleanup crew will pass up a tasty road kill.

CLEAN-UP CREW No. 2 continuedOne segment of the crew that receives little attention is the flesh-eating bugs and larva. These organisms which are down the scale in the food chain speed decay and dispose of the food not consumed by the larger animals. Viewed by many as repulsive, these diligent laborers are performing a necessary task in the over-all scheme of life.

Certain animals depend on others as their food supply, and there is a great interdependence between various animal groups one upon the other. The whole process is one involving the transfer of energy from one organism or form of life to a different one.

This chain begins with plants converting the sun's rays into food energy. Then, through a series of steps involving an animal which feeds on plants being fed on by another animal, and in turn finding itself comprising the food source for still a different animal until the process reaches a terminal point. An example of a simple food chain is one in which a worm living in the soil feeds on fallen leaves and other plant material. The worm is eaten by a bird which in turn is caught and eaten by a ferral cat. The cat is the end of this particular chain. Only through its own death, perhaps from being struck by a car, the energy is reconverted by the scavengers and picked up in another food chain. Since scavengers occur at all levels of the cycle, they are constantly recirculating the energy.

All of the animals in the scavenger group, whether big or small, aerial or terrestrial, have one thing in common. They are caught up in the struggle for food. The road kills which appear as an unnecessary waste come as an unexpected windfall to the scavengers. They are afforded the benefits of food without the problem of securing it through other means.

Since there is little that can be done to eliminate or even reduce the highway kills, it is fortunate that these scavengers assume their duty so willingly. Nebraska's roadsides are cleaner because of them.

THE END 14 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

LAST-MINUTE HONKER

All hope for success depended on this flock of Canadas. We waited eagerly for them to make their playIT WAS seven minutes before quitting time and the geese were 400 yards away, still undecided on their flight path. Motionless beside the blind, my face buried in the frost-seared grass and weeds of its camouflage, I heard Don's whispered instructions.

"If they swing our way, take the one on the left."

The small flock circled over the narrow channel, straightened out and flew toward us with exasperating slowness. Two hundred yards, one hundred, fifty. Then they were above us, white grinning patches bright in the fading rays of the November sun, and their huge wings buffeting the air with a keening sigh.

Don and Gene popped out of the blind, pump guns spewing shot. The big gander faltered, dropped 25 feet, regained his balance, and flayed his heavy wings in a desperate effort to rejoin the startled flock. I swung the muzzle of the little automatic above his head and slapped the trigger. It was enough. The big Canada folded and plunged into the icy waters.

This last-minute shot climaxed two days of hunting for Gene Hornbeck and myself. We had been waiting along the North Platte between Lake McConaughy and Garden County Refuge southeast of Oshkosh. Twice before hunting fortune had half smiled and then turned away as we tried to bag one or two of the thousands of Canadas that traded between the big lake and the safety of the refuge.

Late in the afternoon of the first day I shot at a

low-flying honker. Even as I fired, I knew my lead

JANUARY, 1964

15

was too short. The charge of No. 4's went home into

the heavily feathered body behind the wings, but it

was not enough. The big bird slanted downward to

the waiting gun of another hunter. His second shot

was the coup de grace. Later, he offered me the

goose but it was definitely his prize. I doubt if I

could have recovered the wounded honker in that

tangled mass of willows, reeds, and sunflowers of the

mud flat and I reluctantly declined his generosity.

was too short. The charge of No. 4's went home into

the heavily feathered body behind the wings, but it

was not enough. The big bird slanted downward to

the waiting gun of another hunter. His second shot

was the coup de grace. Later, he offered me the

goose but it was definitely his prize. I doubt if I

could have recovered the wounded honker in that

tangled mass of willows, reeds, and sunflowers of the

mud flat and I reluctantly declined his generosity.

The next morning, Gene racked a single hard but the screaming wind carried the bird across the river and into the refuge beyond. Lacking a boat, my partner could only watch as the bird hit the ground, recovered, and hot-footed it into the brushy refuge.

Indications that this hunt would not go according to plan came early. Glumly, Conservation Officer Don Hunt of Oshkosh gave us the bad news when we arrived the night before.

LAST-MINUTE HONKER continued"The river has changed since last season and

my blinds are no longer at the edge of the channel.

The geese won't decoy to my spread since there's

so many rafted up in the refuge. They're flying

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

higher and faster than ever and are real spooky

from the hunting pressure.

higher and faster than ever and are real spooky

from the hunting pressure.

"About all I can offer is pass shooting," he added, "and you know what that means. High, hard shooting at long ranges and plenty of skyscraping hunters to drive them even higher.

Neither of us had the proper shotguns for pass shooting. Originally, we planned to shoot geese and a few ducks over decoys at 35 to 40 yards. Gene was using his 20-gauge auto. I was loaded with 2%-inch Magnums in my side-by-side double. As a compromise between pattern and penetration, No. 4 shot was selected.

The next morning was a frigid mixture of mist, scudding clouds and a polar wind as cold as a witch's kiss. We slogged through the mud flats and reached the blinds just as legal shooting time started.

Geese and ducks were trading back and forth over the channel some 50 yards beyond the blinds. In spite of the sour weather they were flying extremely high and fast. To the left of us, another group of hunters was saluting the passing birds with a steady barrage, driving the spooky waterfowl even higher.

We spent a fruitless day in the marsh except for Jim McCole's score on a highflying single. Jim, a conservation officer from Gering, had joined us later in the afternoon. Using a 10-gauge Magnum with three-inch shells, Jim decked his bird at more than 70 yards. A few minutes later, I got the best shot of the day at the goose that went down before the other hunter.

That night in the motel Gene summarized our problems.

"The geese are just too high for us and tomorrow will be worse. The weather report claims clear skies and high winds. We need Magnum loads with the heaviest shot we can get. Our best is Double-0 buckshot in three-inch 12-gauge Magnums or even a 10-gauge. All of which we haven't got and can't get."

Double-0's have nine heavy pellets in each shell. They are big enough to keep (Continued on page 36)

WINTER'S FOR TROUT

Pine Ridge brownies forget the thermometer when flies float by by Gene HornbeckELBOWING IN on top of the bank, I eased the fly rod over the edge and looked for a spot to drop my minnow-baited hook. Below, the tumbling waters of White Clay Creek spilled out of a deep, placid pool into a swift, watercress-bordered run, then fanned out over a gravel riffle.

A flick of movement near the end of the riffle caught my eye. Closer examination revealed a brown in the 15-inch class nosing into the gravel bottom of the stream. At first I thought the fish was feeding on nymphs. Its antics, though, were too vigorous for this, and what I was seeing was the finishing up of a nest for spawning. Soon the male joined her, and 30 minutes later the new eggs were covered with a light layer of fine gravel. The goings-on were so fascinating that I almost forgot that I'd come to catch fish.

It was mid-November, late for the browns to be spawning, due to the unseasonably warm fall. The weather was a crisp 45° and the cottonwoods along the valley of the White Clay stood nude of foliage. Crows called noisily from the Pine Ridge above and a flock of pinion jays swooped into the trees around me, then flared away in alarm.

Leaving the spawners undisturbed, I walked down to the next bend to meet my companion, Hank Pisacka. The Hay Springs resident is one of those rare flies-only trout fishermen. More specifically, he prefers them dry.

To Hank, the fall and winter hold only the expectation of spring; a big brown swirling to the surface for a dry. This was the twilight of his trout-fishing year. As a bait fisherman, I looked forward to winter and the uncrowded streams, and to tangling with a real lunker in the frigid waters.

A bright sun began to bring the temperatures

up and Hank switched to a thinly dressed dry. He

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

touched it up with a spray of fly dope from an aerosol can, stalked down into the stream ahead of me,

and cast to the lip of a quiet pool. The gray hackled

fly floated jauntily along the surface.

touched it up with a spray of fly dope from an aerosol can, stalked down into the stream ahead of me,

and cast to the lip of a quiet pool. The gray hackled

fly floated jauntily along the surface.

"I noticed a few insects in the air," he offered, as he recast, "Bet I can get one to take that floater."

He picked up his line, whipped a couple of false casts to dry the fly, and then dropped it delicately on the water again. I wasn't about to take his bet after seeing him handle the rod. He had the touch of an artist. Hank dropped to his knees to cut down his silhouette, and duck-walked upstream to try the run above the pool.

The line arched downstream, came back under the power of the rod, and the fly settled on the run without a ripple. It had floated only a couple of feet when I saw the surface dimple under Hank's offering. The gray hackle evaporated almost magically. The rod tip came up and then began to dace against the battling trout. A couple minutes later, a 10-inch brown slid into Hank's waiting hand.

"You proved a point," I said, looking over the fat little trout. "I don't think I've ever seen a fish take a dry this time of year."

"It's probably the latest I've ever taken one," he said, creeling the trout. He had scored on nymphs in late fall and early spring when there are no insects on the wing.

To Hank the nymphs, bucktails, and streamers were good the year-round, with nymphs the mainstay of the trout's winter diet. The Hay Springs angler fishes his flies slowly and carefully during the cold months. The trout are not as active and then have to be teased into taking.

Hank's trout country covers Dawes and Sheridan counties. Streams such as the White Clay, Larrabee, Big and Little Bordeaux, Beaver, Pine, and Deer creeks are all trout producers. Some are better than others, but on the whole, all can produce a nice trout stringer. Hank figures he has taken as many or more trout from the streams close to his home than he does in the western Pine Ridge waters in Sioux and Dawes counties. He did add, however, that for big brownies the headwaters of the Niobrara are hard to beat.

We fished the White Clay for about three hours, with my partner scoring on four nice browns. I had lots of action on minnows and finally matched Hank's number. The fish were hitting good, but evidently were taking the minnows short. I was missing them when I set the hook. One 10-inch fighter took my offering three times before I finally set the barb in him.

The best trout of the day was a 15-incher that drifted in slowly behind my minnow as I retrieved it through a narrow run bordered by water cress. Recasting to the tail of the run, I quickened the pace and the trout darted out and grabbed the bait. As he zipped back for cover, I dropped the rod and fed him line. Tightening up the line, I felt the fish throbbing and set the hook. The trout came speeding out and torpedoed along the surface for an instant. Then the line went slack. I had nicked him, but as usual, the big one got away.

To sample another stream in the area the next morning I drove west to Big Bordeaux Creek. Hank had to tend to his rural mail route and couldn't join me. The Bordeaux is about the same type stream as White Clay. It flows a little faster with some good runs and perhaps has a fewer big pools.

My first fish was an eight-inch rainbow taken on a minnow. Knowing (Continued on page 37)

JANUARY, 1964 19

GO PREPARED

Maximum of clothesw and minimum of gear is the ice fishing formulaPART OF the satisfaction derived from a fishing trip is getting out of the house unnoticed. Most anglers, unfortunately, require so much equipment that a hasty retreat is difficult if not impossible. It is a well-known fact wives can come up with a thousand jobs to be done around the house if given two minutes warning.

Any fast-thinking ice fisherman can be half way down the block well under this time limit. That's one of the beauties of hard-water fishing. The equipment necessary is compact and much of it can be carried in a minnow bucket. This makes the ice fisherman a veritable greyhound in comparison with his warm-weather brethren.

The biggest item for the well-equipped ice fisherman is clothing. Don't let the January and February sunshine fool you, for the temperature during these months is hugging the zero mark and it's sure to be a lot colder out on the ice where the wind has a chance to really blow.

Mobility isn't as important as in hunting so the amount of clothing to be worn can be almost endless. Start with quilted underwear made of a synthetic material covered with a thick outer shell. Thermo-knit underwear is also good but not quite as warm. With this type, more outer-clothing has to be piled on.

Next come the feet. Quilted socks topped with thermo boots are the answer here. A pair of light cotton socks can be worn under the quilted ones to absorb moisture.

Trousers with knitted cuffs are real cold beaters.

Tucked into the boots, they retain body heat as well

as keeping out frigid blasts. And a wool shirt with a

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

sweater or two underneath will ward off anything

short of a full-scale blizzard.

sweater or two underneath will ward off anything

short of a full-scale blizzard.

Several sets of inexpensive cotton gloves will keep your hands warm while handling baits or pulling in a fish. As soon as one pair gets wet, discard it and put on another. A pair of warm wool mittens keep your hands warm the rest of the time.

Headgear depends on the individual, but the more of the head and face that can be covered, the better. Quilted caps with ear flaps protect everything but the face and are fine under most conditions. Pullover wool caps cover the entire face and head, except for an opening for the eyes. This portion of the face can be protected by one-piece goggles which have interchangeable lens.

Last but not least comes the coat. Nothing beats a down-filled coat for warmth. Get one with a parka hood or oversized collar and you're all set to waddle out on the ice, no matter what the weather.

Some of your summertime fishing gear can be utilized for ice fishing. A styrofoam minnow bucket is excellent, as its insulating properties will keep minnows from freezing. A short casting rod fits into the hard-water angling picture, although a commercial ice-fishing rod is better.

Commercial rods consist of a wooden handle with a 12 to 24-inch light limber rod. These sell for around $1. Sporting two to six-pound monofilament line, they're rods used mostly on panfish and perch.

Tip-ups with heavier line are best for northern pike, walleye, and other larger species. One type is rigged to keep the reel underwater to prevent the line from freezing. A red flag on a piece of thin flat wire is bent over when baited and is released when a fish strikes. Another tip-up is made with two pieces of wood fastened crosswise. It is set over the hole so three of the legs are resting on the ice with the fourth over the hole. When the fish strikes, the leg is pulled under and the opposite leg flipped up to signal a strike.

NEBRASKAland fishing regulations allow ice fishermen to use up to 15 hooks, either singularly or five to each line. A new regulation that went into effect January 1 is of particular interest to the hardwater angler. It prohibits keeping northern pike under 24 inches caught east of Highway 81, except in the Missouri River and its oxbows.

There are baits aplenty for ice fishermen. Live baits include minnows, corn borers, "mousees," goldenrod grubs, meal worms, and aquatic insects and nymphs. Large minnows are best on northerns and walleye with the others hungry for all the rest, including small minnows. A particularly good bait on perch is a perch eye taken from a freshly caught fish.

Lures are just as effective, used either by themselves or with bait attached. Most lures are of the spoon variety and give out their best action when jigged up and down. Some lures and ice flies have bucktails attached to make them even more attractive.

Augers have just about taken the place of spuds for the serious ice angler. An auger can go through 18 inches of ice in three or four minutes. Once the hole is finished, a skimmer to keep it clear of slush comes into play. This can be appropriated from the kitchen or made from a one-pound coffee can liberally punched with holes.

Finding an ice fishing spot in NEBRASKAland is no problem. Almost any lake that freezes over in winter is a likely prospect. Just make sure the ice is thick enough and watch out for cracks and air pockets. Prime waters range from Lake McConaughy's whopping 37,000 acres down to small farm ponds.

Pick any day in January and February when the wife is busy and break out of the house for the tops in wintertime fishing pleasure. The weather may be cold but the fishing could be hotter than a firecracker.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 21

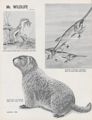

Mr. WILDLIFE

UNDER THE magic of his talented brushes, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard makes Nebraska wildlife come vividly to life. As staff artist for the Game Commission for the past 15 years, Pritchard has drawn his way into the hearts of everyone who knows and enjoys wildlife paintings and sketches.

He is best known for the painstaking detail that

goes into the fauna series drawings that appear

each month in OUTDOOR Nebraska. Whether it be

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

a lowly earthworm or majestic mule deer in the

wilds of the Pine Ridge, Pritchard makes each a

study in motion.

a lowly earthworm or majestic mule deer in the

wilds of the Pine Ridge, Pritchard makes each a

study in motion.

Pritchard's illustrations have appeared in outstanding exhibits throughout the country, including such renowned halls as Joslyn Art Museum. OUTDOOR Nebraska proudly has a Pritchard exhibit of its own with 16 of his finest contributions in the past years.

THE END

Mr. WILDLIFE

continued

Mr. WILDLIFE

continued

Mr. WILDLIFE

continued

Mr. WILDLIFE

continued

DEEP-FREEZE BAITS

Finding your own is the answer to solving wintertime bait problemsICE FISHING is fun and excellent sport, but like eating raw oysters, it takes some getting used to. You might try to wriggle out of an invitation by explaining that bait is too hard to come by when the north wind is doing its best to move Nebraska into the Gulf of Mexico. But if your buddy is an experienced ice angler, he'll checkmate you quicker than you can mumble, "It's too cold."

Live bait for ice fishing isn't too hard to find if

you know where to look and have the courage to

brave the elements while doing it. Besides, searching

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

for bait is good practice for the infinitely colder ice

fishing. It's sort of a warm-up with reverse English.

for bait is good practice for the infinitely colder ice

fishing. It's sort of a warm-up with reverse English.

Small minnows are the most popular come-on for hard-water line dunking. In solid second place are the grubs, larvae, and nymphs of various soil and aquatic insects that are waiting out the winter in a dormant or semidormant state.

Finding minnows is no particular chore. Pockets in flowing streams, sheltered backwaters in shallow ponds, and the little pools below falls and riffles are good places. A small mesh net or a small seine and a few swipes will garner enough bait fish to keep you freezing for hours on a Sand Hills lake. If a perch or two succumb to your offerings, their eyes are a natural bait for more of their brethren.

Keeping minnows from freezing while on the ice can be accomplished in a number of ways, depending upon your own ingenuity in keeping them comfortable while you slowly congeal. A patented styrofoam bucket with its heavy insulation is an excellent container. Frequent stirring with your ice skimmer or a small stick will also keep scum ice from forming Commercially available oxygen tabs dropped in the bucket at intervals will forestall freezing for a time and also keep the bait lively.

Lacking minnows, the ice fisherman can turn to red worms or night crawlers, but finding them is sometimes a bit of a task. Sheltered spots near the edge of a building, ground protected with low-lying vegetation, or the soil along a thick hedge will often produce a batch of garden hackle, even though the ground is flinty-hard elsewhere. You'll find the worms deep and the crawlers deeper still, but they can be spaded up.

If digging your own when the mercury is flirting with zero doesn't strike a responsive chord, try commercial bait dealers. Many raise their own worms and will sell you a supply. Perhaps you have your own worm box in garage or basement. If so, there's no sweat.

Another fine ice-fishing bait is the mousee grub. These off-white larvae, with the two hair-like feelers out front, are usually sold by commercial baiters. Put them in a small box with some corn meal or dry sawdust. When on the ice, keep the box in your inside pocket to keep the grubs from freezing. Though soft and a bit mushy, they are deadly on panfish. Perch and bluegills consider them a delicacy. Fished properly, they produce heavy stringers.

A smart little grub makes his home in the goldenrod. In that round ball or gall on the stem lives a worm that makes a good hard-water bait for practically every winter feeder. Gather a half gross or so of these galls and take them home. Keep them stored in a cold place until you're ready to fish. Then split the gall with a penknife and extract the bait. Not all of the galls will contain worms, and you can avoid dry runs by checking the underside for a small hole. If there, it usually means that the grub has long since departed.

Be sure to keep the galls in a cold spot. If they become too warm the tenant emerges and is lost. If you want to save time, open the galls a day or so before the planned fishing trip. If so, store the grubs in a box with some sawdust or oatmeal and put them in the vegetable drawer of the refrigerator. This might take some squaring with the lady of the house but the grubs are harmless. Like mousees, protect the unhoused grubs from freezing until ready to hook.

For the way-out angler who wants to try less common baits, there are a number available, but finding them is almost as specialized as finding the fish. Meal worms are excellent. Check elevators, granaries, mills, or other spots where grain is discarded or scattered. These little characters can be stored for several days in temperatures of 40° to 50°. Again, the refrigerator serves well for storage.

Mud dauber or paper wasps' nests are good hunting grounds for larvae-type baits. It is best to do your grub prospecting where you find the nests. Bringing the whole shebang into a heated basement or garage can create problems, especially when the warrior insects are roused from their winter torpor by the warmth.

Corn borers are another excellent bait. Find some standing stalks and split them open. Not every stalk will contain a borer, but enough of them will to make the effort worthwhile. Rotted (Continued on page 37)

JANUARY, 1964 29

LURE OF THE TRAP LINE

No mortgage lifter but hobby brings rewards and money, tooFURS, NOT gold or land first drew men to the rugged untamed West. Grizzled individuals often alone, sometimes in groups, fanned out from the settled East to satisfy the demand for clothing fashioned from rich furs.

The last of the mountain men have faded into the past, their names all but forgotten. But in their quest for furs they opened the West to civilization. Their trails became the roads for creeking pioneer wagons. Even today's modern highways follow where the moccasined feet of trappers once trod.

The drop in fur prices and competition with synthetics

has all but eliminated the professional trapper

30

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

but, there are still hardy men who follow the trap

line. For the most part, however, trapping has been

taken over by youngsters. They have the spare

time needed for the endeavor and it means money

for extras that they have their eyes on. The initial

investment is small and can be recouped in a week

or two by the industrious beginner who runs his

traplines daily.

but, there are still hardy men who follow the trap

line. For the most part, however, trapping has been

taken over by youngsters. They have the spare

time needed for the endeavor and it means money

for extras that they have their eyes on. The initial

investment is small and can be recouped in a week

or two by the industrious beginner who runs his

traplines daily.

Trapping is no get-rich-quick trade for the individual. Prices swing from one extreme to another. Fashions dictate value and a woman's whim can change them overnight. Mink bring from $2 to $15 depending on condition, size, and the number of pelts brought in by the individual. Raccoon, the old standby, fetches from 25 cents to a dollar. A muskrat generally brings around $1.

Prices vary with the size of the trap from an outlay of $1.29 for a No. 1 which is used for weasel or skunk, to $2.59 for the No. 4, the most common rig for beaver. Muskrat, probably the easiest of the furbearers to catch, takes a No. 1% trap and sells for $1.45.

Neophyte trappers should remember to test the action of a trap to make sure it works freely before placing it in a set. Check all moving parts. This is best done by setting the trap and snapping it a time or two before heading out. Care of traps is important to their successful operation. At the close of the season, they should be cleaned and hung in a dry place. Oiling is not considered necessary.

Many who began trapping as youngsters for the money continue the endeavor as adults for the sheer love of it. There are few activities that require a closer communion with the outdoors. Youngsters learn to read signs almost immediately and to become intimate with the most minute parts of the stream and field.

Muskrat and raccoon make up the bulk of the trapper's bag here. Although mink pelts command the highest prices, this wily member of the weasel family is not as easily taken.

Across the snow and along the stream beds the tracks of animals spell out high drama. Reading the signs, it is possible to see where an owl has swooped up a squealing, kicking rabbit. Near a pocket of open water, the prints of a raccoon disclose midwinter crawfishing.

Normally the trapping season on beaver, muskrat, and mink opens November 15 each year. There is a year-round trapping season on foxes. This season mink is fair game until January 15. Trappers can take beaver and muskrat through March 15. Fox, raccoons, skunks, and other furbearers can be taken year-round.

There are no bag or possession limits and the entire state is open. This does not include state-owned lakes and marshes or areas closed by federal, state, or municipal law.

All furs must be disposed of within 10 days after the close of the season. Written permission must be obtained from the Game Commission to retain furs for a longer period.

An investment of $2.50 in a trapping permit opens the door to an entirely new field of outdoor activity. Traps are basically the same as those carried by the buckskin-clothed mountain men.

Trapping provides an excellent opportunity to step back in time. Prime sport with a profit motive is the way some men have referred to trapping.

Nebraska abounds in game of many sports. Don't pass up the opportunity to broaden your outdoor experience. Try trapping this season. You might even pelt out enough mink to make the little woman a cape.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 31

HOW FISH BREATHE

IF YOU are a farmer, every time you allow muddy drainage waters to flow into a nearby stream you are helping to ruin fishing. If you live in a city, you are partly responsible for having changed your favorite nearby trout hangout into a trash-fish stream. Many of your everyday activities may be decreasing your fishing success by suffocating your finny friends. Depletion of dissolved oxygen in water, due to bacteriological decomposition of introduced organic matter is often the cause of fish kills in our lakes and streams. Every time we allow the community, of which we are a part, to pour raw sewage, industrial wastes, radioactive wastes, or even hot water into a nearby water course, we are decreasing our chances for future fishing pleasure.

There is no definite amount of oxygen that can be said to be absolutely necessary to sustain fish life. Moreover, fish differ greatly in their requirements. Unfortunately most game fish require more oxygen than many rough fish and hence often die while the rough fish survive. When oxygen is about one-third of the normal amount present in the summer, the fish are in danger. At times fish may survive on much less, whereas at other times they may die when this point is reached. These differences may be due to the condition of the fish and to the temperature and other physical and chemical differences in the water.

A knowledge of the way in which fish breathe may help you appreciate their need for a clean, well aerated environment and, if you help prevent pollution, thereby improve your fishing success.

Superficially, there is little resemblance between

the respiratory system of man and that of most fish.

The respiratory organs of fish are gills located in

the gill slits and attached to the visceral arches.

Each gill consists of a double row of slender gill filaments, with every filament bearing many minute

transverse plates covered with thin tissue and containing many capillaries. Each gill is supported on

a cartilaginous gill arch and its inner border has

32

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

expanded gill rakers which act as a strainer to prevent food from clogging the gills.

expanded gill rakers which act as a strainer to prevent food from clogging the gills.

A fish respires by expanding its pharynx and taking water in through the mouth. Then the mouth is closed or in certain species, oral valves close, the pharynx is contracted, and water is forced out through the gill slits. Water cannot go down the esophagus, for this is collapsed except when swallowing. In sharks, each gill slit opens independently at the body surface.

The gills are protected in the gill slits, they have a large surface area, the blood and external environment are in close proximity, and gas exchange occurs readily as water passes over them. In addition, the body gains or loses water through the gills, and some nitrogenous wastes are excreted here.. The saltwater fish also excrete salts through the gills. These fish live in an environment in which the salt concentration is greater than that in their bodies so they tend to lose water by osmosis. They must drink large amounts of salt water and then excrete the salts by specialized cells in their gills.

by Dr. Arden R. Gaylin Respiration is complicated process for our finny citizens of the deepA number of fish live in water which has a low oxygen content, and they supplement gill respiration by occasionally gulping air. For example, carp can live in heavily polluted water having an oxygen content of less than one part per million. There is much more oxygen in the air than in water and carp can extract it as long as their gills remain moist. On the other hand, trout do not have this ability and require oxygen concentrations of and in excess of four to five parts oxygen per million parts water.

While depletion of dissolved oxygen, due to bacterial decomposition of organic wastes, is probably the most common cause of fish kills in our lakes and streams, a number of other pollutants may adversely affect fish by interfering with their respiration. High temperatures, excess turbidity, high concentrations of carbon dioxide, and certain toxic industrial wastes can markedly increase the susceptibility of fish to deficiencies of dissolved oxygen. Brook trout and silver salmon have been kept alive under laboratory conditions at dissolved oxygen concentrations of two parts per million at moderate temperatures (64.4°). By comparison, dissolved oxygen concentrations well above the three parts per million can be quite rapidly fatal at fairly high temperatures (77° to 80.6°).

Water used for cooling purposes in industrial processes may become so hot and be of such quantity that it may substantially raise the temperature of a receiving stream. In trout streams even a slight rise in temperature may be undesirable. Few trout, even the most tolerant species can survive temperatures above 82° to 83° even for very short periods. Furthermore, when stream temperatures are raised so that they consistently exceed 70° in summer, even though they may not be lethal, environmental conditions become less favorable for trout and more favorable for minnows, suckers, and other warm-water fish. This change is largely due to differences in the respiratory and metabolic requirements of these different species.

Clogging or blanketing of the gills of fish with matter suspended in water, such as soil particles, fibers, or precipitated matter is not unusual when fish are exposed to various toxic solutions containing the suspended material. Injury to the gills by the harmful dissolved substances probably results in the inability of the fish to keep their gills clean. Fish in extremely turbid waters may also be affected by the gill filaments becoming clogged with clay particles from the water thus interfering with normal gaseous exchange.

Any one of a great number of toxic substances can render water unsuitable for fish. Industrial wastes such as effluents from canning and sugar factories, oil refineries, pulp mills, metal finishing and electroplating plants, and steel mills, all of which are common water pollutants can be highly toxic to fish.

They may contain oxygen-depleting organic material, acids or alkalies, salts of various metals, cyanides, phenols, and numerous other toxicants. Extremely poisonous insecticides, herbicides, and algicides can cause serious mortality of fish when they are purposely added to water or are accidentally introduced by being washed into watercourses from land by rain. The injurious action of many of these substances, which can be fatal to fish when dissolved in water, is largely external.

Damage to the delicate tissues of the gills and impairment of their respiratory and excretory functions is a common cause of injury. The circulation of blood in the gills may be interfered with by an accumulation of mucous, which coats and clogs gills, immobilizing the gill filaments. The salts of many metals such as lead, copper, zinc, and mercury, particularly, produce this coagulation of mucous on gill surfaces and result in respiratory failure in fish. Such salts may gain access to streams from industrial plants and be largely responsible for a complete absence of fish in streams receiving effluents from heavily industrialized areas.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 33

A NEBRASKAland PRODUCT BOOKS-BISON

Vivid word pictures recapture throbbing tempo of early westIF, IN THE long hours between midnight and dawn, the shades of Crazy Horse, Custer, Print Olive, Dull Knife, and "Doc" Middleton stride through the corridors of Nebraska Hall in Lincoln, they probably feel right welcome. For certainly, the University of Nebraska Press is doing all it can to make the rawhides of Western Americana feel at home.

Publishers of the popular Bison Books, the Press is busy publishing the experiences, tales, folklore, and exploits of paleface and redskin who settled and sometimes unsettled the raw, lusty land, west of the Missouri, less than a century ago.

Some of the books turned out by the University of Nebraska Press are reprints of classic works that were originally published elsewhere and later went out of print. Others are original books, authored by Nebraskans and other Westerners. The Press publishes about 45 new titles each year. Most of the volumes are paperback editions, priced at minimum cost and appealing to the general reading public and the amateur scholar of western lore.

University of Nebraska Press, located in the former Elgin Building, now renamed Nebraska Hall, is one of 52 college and university presses in the United States. Prime mission of these is the publishing of books of scholarly merit on English Literature, science, and other fields usually associated with higher education. The University Press differs somewhat from other school presses in that it devotes about one half of its annual output to books about the western country with emphasis on Nebraska.

The popularly priced books are filling a void that exists in Nebraska and a number of other western states. According to Bruce Nicoll, director of the Press, many of the western states are still too close to the pioneer period to evaluate the rich history of their early years. Bison Books attempts to bridge this gap between the present day and the pioneer.

Nebraskans led a full and exciting life in the early days of the territory. Their victories, their defeats, their very lives are the basis for great stories which can be read and enjoyed while developing a richer appreciation for the mavericks who left indelible marks on the history of the state.

Bison Books, through their publications, attempt

to bring out a broader understanding of the urges,

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

impulses, and conditions, that drove men and women

to buck a violent land, subdue hostile Indians, and

wrest a living from a reluctant soil to settle in this

region and carve out and establish a state with many

unique features.

impulses, and conditions, that drove men and women

to buck a violent land, subdue hostile Indians, and

wrest a living from a reluctant soil to settle in this

region and carve out and establish a state with many

unique features.

Fortunately, a great deal of material still exists pertaining to the early days of Nebraska and other western states. The Bison Books seek out, compile, and publish this material with two objectives. One, to give modern day residents more enjoyment and appreciation of their rich heritage and second, to preserve the early history of the region for future generations.

The University Press is accomplishing its objectives. In the last four years, there is a growing interest in the state and its history. Authors and researchers are contacting the Press almost daily with outlines and story ideas. The Press is also contacting those who might have something to contribute to the growing collection of Western Americana.

For example, a Sand Hills rancher, not a professional writer, is presently working on a book about "Doc" Middleton. Doc was a real hellbender of his day. Operating out of the Sand Hills during the 1880's and 90's, he was quick with other people's possessions and quicker with his gun. Finally, he died in jail in Wyoming, but during his prowling days, this badman cut a wide swath through Nebraska and adjoining states.

Press Director Nicoll and his staff are encouraging the rancher to continue his work on Middleton. They believe the story will contain all the ingredients for a fine, well documented, and authentic book that will contribute to Nebraska's rich past.

On the other end of the scale, a Lincoln man is working on a book about Judge William Gaslin, Jr., an early day judge who was a colorful and respected figure in the state's early legal circles. Judge Gaslin, an easterner by birth, came out here in the latter days of the last century. A lawyer by profession, he became a judge in a district which comprised almost half the state.

When he tired of droning testimony and the courtroom antics of the opposing lawyers, he would adjourn, get rip-roaring drunk and otherwise paint the town red. When he sobered up, court would be reconvened and the case would go on. He often held court with a loaded carbine on the bench or a Colt Peacemaker handy by. In spite of his nonjudicial behavior, Judge Gaslin was an excellent jurist.

Bison Books are not created overnight. Not counting the author's work which may take years, the actual production of a book takes at least six months after the final draft is approved and accepted.

Although most of the books published by the University Press are paperbacks, a number of more expensive hardbound volumes are turned out and distributed throughout the United States. Books set in specific areas seem to enjoy their best sales in that region.

Among the popular favorites are Pinnacle Jake, a story of the western cattle country toward the close of the 19th Century, Reminiscences of a Ranchman, and The Indian Wars of 1864. Reprints of Mari Sandoz's classics also enjoy a ready market.

With the lofty purpose of preserving the unique flavor of Western Americana and arousing a pride and awareness within the average reader of his state and region, the Bison Books have yet another attribute that is too often overlooked when authors and critics ride off on their pink clouds to find the reason why for such and such a book.

Bison Books are downright enjoyable to read and in the final analysis that is the acid test of any story. Bison Books are one hundred proof in that respect.

THE END JANUARY, 1964 35

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

15 cents a word: minimum order $3 March closing date, February 1 DOGS AKC LABRADORS: Excellent field-trial pedigrees. Few young dogs, some field-champion sired. Four litters for fall delivery, $50 up Kewanee Retrievers, Valentine, Nebraska. Telephone. 26W3. AMERICAN WATER SPANIELS: Fine hunters, retrievers. Choice puppies. AKC registered. John Scofield, Jonesburg, Missouri. FOR SALE: Vizsla dogs. All ages, championship ancestry. F.D.S.B. and A.K.C. registered. Wayne Hoskins, Enders, Nebraska. Telephone: Imperial TA 3-4858. FOR SALE: Vizslas, pups F.D.S.B. registered champion bloodlines. Whelped August 21, 1963. Ed Scott, 1332 17th Avenue, Mitchell, Nebraska 69357, Telephone 623-5011. GUNS NEW, USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS —Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca, Colt, Ruger, and many others in stock. Buy, sell, or trade. Write us or stop in. Also live bait. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, just off U.S. 136, Fairbury, Nebraska. MISCELLANEOUS NEW 20-PAGE CATALOG contains pictures, specifications and prices of Marlin Guns for 1964. Thirty-five different models of rifles and shotguns in all . . . at prices ranging from $17.95 to $126.95. This comprehensive catalog gives you all the information needed to select the best gun for anybody . . . young or old . . . novice or marksman . . . target-shooter or big game hunter. You'll also learn why America's finest marksmen and huntsmen agree . . . "you pay less . . . and get more from a Marlin." Bonus: Copy of the Bill of Rights, guaranteeing Americans the right to keep and bear arms, printed on parchment paper and suitable for framing included free with every catalog. Write Department 165, The Marlin Firearms Company, New Haven 2, Connecticut, U.S.A. ATTENTION HUNTERS, free circular of game calls. All kinds, crow, turkey, deer. Bell Hardware, Clanton, Alabama. SMOKE FISH, GAME. Build inexpensive electric smoker. Instructions, drawing, recipes. $1. Make summer sausage, salami, jerky from game. Instructions, recipes. $1. Oldtimer John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840. TRAP NIGHTCRAWLERS, earthworms by thousands. Instructions, drawing, $1. Oldtimer John, Kootenai, Idaho 83840CATCH THEM ALIVE AND UNHURT!

Catches more! Easy to use! Amazing HAVAHAKT trap captures raiding rats, rabbits, squirrels, skunks, pigeons, sparrows, etc. Takes mink, coons without injury. Straying pets, poultry released unhurt-Easy to use — open ends give animal confidence. No jaws or springs to break. Galvanized. Sizes for all needs. FREE illustrated practical guide with trapping secrets. HAVAHART, 246-J, Water Street, Ossining, N.Y. Please send me FREE new 48-page guide and price list. Name AddressTOP QUALITY HUNTING COMPANIONS

VIZSLAS exclusively GRAFF'S WEEDY CREEK KENNELS Route 3, Seward, Nebr. Phone 8647FIELD-TRIAL WINNING BLOODLINES:

Ripp Barat, Brok Olca, Rakk Selle & others. Top hunting stock, fully registered. Stud Service. Breeding Stock fully guaranteed. Reasonable prices. Write for free information on the type of dog you want. VIZSLAS MILE-HIGH VIZSLAS J. R. Holcomb Box 177 Englewood, Colo. Phone 781-1860 Area Code 303 ** V AT STUD — RIPP BARAT'S RIPPY Whelped Jan., 1962 A.K.C. No. SA-132646 F.D.S.B. 684979 Sire: Ripp Barat; Dam: Sissy Selle Wins & Placements of Ripp Barat's Rippy Vizsla Club of America, Fall '62: 1st place Puppy, 2nd place Derby. Mississippi Valley GSHP, Spring '63: 2nd place Derby, Vizsla Club of America, Spring '63: 4th place Derby. Weimaraner Club, Alberta, Canada, Fall '63: 2nd place Derby, 2nd place Shooting Dog Slakes. Vizsla Club of America, Fall '63: 1st place Open Derby, 2nd place Open Limited All Age Stake, 3rd place Open All Age, 4th place Amateur Gun Dog Stake.LAST HONKER

continued from page 17their velocity and pentration out there at 50 to 65 yards. They'll get through feathers and bones to the vitals. If you hit, it's a dead goose, if you miss, it's a clean miss eliminating crippling shots.

Unfortunately we couldn't scrounge any Double-0's that night and had to settle for a couple of boxes of high-based No. 2's. Don, who couldn't hunt until late in the afternoon, lent me his 12-gauge slide-action, claiming he could get another for the afternoon. Hope renewed and feeling somewhat better equipped for the next day, we sacked out.

Don's brothers, George and Ron, joined us in our early-morning walk over the mud flats to the blind. It was clear and bitter cold along the river as the sun came over the surrounding Sand Hills. George and Ron set up shop in the other blind and after laying out extra shells and stowing lunches and camera gear, we were ready for the day.

Skein after skein of Canadas honked over the channel, flying extremely high and fast. Ducks milled and circled over the refuge, their raucous quacking adding to the yelping of the geese.

"They're flying mighty fast and high," sighed Gene, as we watched a huge flock of Canadas pitch into the refuge. "Maybe some of them will come in lower, especially as the big lake gets rougher and drives them out."

After Gene's unfortunate experience with the only low-flying single of the morning, I left the blind and walked into some willows to shoot a couple of mallards from the flocks that streamed over a projecting sand bar.

A pair of drakes came over, just in range. I missed the lead bird, caught up to the follower with my second shot, and watched while he fluttered down in front of Gene's blind. I missed two more and then flubbed an easy shot before I realized what was wrong. I couldn't swing Don's heavy 12-gauge fast enough to come up behind and pass the wind-swept birds.

I walked back to the blind and picked up Gene's little three-inch Magnum. Three shots later, I had a scaup and a bluebill and decided to call the duck hunting off for the rest of the day in hopes of getting a goose.

From time to time, Ron and George cracked away at passing geese, but the combination of wind and range was too rough. Gene was tempted a couple of times, but let the honkers pass when he decided they were out of reach.

Don joined us about an hour before sunset and after hearing our tales of woe worked out a plan.

"Just before quitting time, the geese

usually leave the refuge and head for

36

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the lake to spend the night. If the first

few flocks get by all right others fly a

little lower. Maybe a flock will come in

low enough for shooting. If it does, let's

pick out one bird and have everybody

work on him."

the lake to spend the night. If the first

few flocks get by all right others fly a

little lower. Maybe a flock will come in

low enough for shooting. If it does, let's

pick out one bird and have everybody

work on him."

Seven minutes before quitting time his plan worked out. We had one goose, victim of a co-ordinated effort to bag one of the wily honkers that ply the channel of the North Platte.

THE ENDWINTER TROUT

continued from page 19the rainbow's fondness for salmon eggs, I switched to a No. 14 egg hook and impaled a single on it. The trout were hanging out in the narrow fast runs along the water cress and an egg floated through the run brought results. I creeled two rainbows quickly and was satisfied that I could take a limit in very little time, so I switched back to minnows in quest of the browns.

A variety of baits are available to the winter trouter. Minnows, salmon eggs, both singles and clusters, and worms are top baits. The fisherman will find a host of small aquatics under logs and stones. Nymphs such as the hellgrammite, stone fly, dobson, and dragonfly are all large enough to be used as bait.

Choose your tackle to fit the needs of the fishing. The salmon egg hook should be small, Nos. 14 or 16, with a short shank. The same goes for fishing with the live nymphs, although the larger baits like the hellgrammite will take a No. 10.

Minnow hooks should be from a Nos. 6 to 10 with a long shank. The hook should be long enough to slip through the gill and hook in behind the dorsal of the minnow. There is a twin-hook minnow rig made that slips in the vent and is eyed so that it hooks into a small clasp tied to the line. This one is excellent for trout since the hooks ride well back and get those fish that hit short.

Monofilament is the preferred line. Thin and nonabsorbent, it picks up very little water and does not freeze in the guides. Six to ten-pound test is good for the bait fisherman. The streamer and nymph fisherman should use two-to-four-pound test.

Fly or spinning rods work well. Many fishermen prefer the spinning rig in a 6V2 or 7-foot light-action rig since the guides are larger and do not ice easy. The action is more sensitive to the light hits of the winter trout.

While some fishermen will be fishing through a hole in the ice this winter, there will be a few that can't wait till spring to hook one of these cold-water battlers. The streams of the eastern Pine Ridge offer lots of winter fun for those few hardy that will dare winter's icy blasts to hook a rainbow or brown trout.

THE ENDOUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

Whistle BaitCALIFORNIA ... A woman impulsively whistled at a golden eagle flying low over her house. To her surprise, the bird promptly flew down and landed on her arm. Not having a falconer's glove on at the time, the big bird's talons scratched and perforated her arm. Her husband comments that it may be unwise to whistle at strange eagles.

Forgot the CalendarPENNSYLVANIA ... A conservation officer noticed an angler releasing a 28-inch walleye. Asking the angler why, he was told the fisherman released the fish because the walleye season hadn't opened yet. The officer then informed the fisherman the walleye season had already been open for a week. The angler sat down and began bawling.

Fruit of the GrapePENNSYLVANIA ... A farmer called a local conservation officer and said he had a red fox lying in his grape vineyard. The officer walked up to the fox which got up and staggered up the row before dropping down again. After the officer shot the fox, thinking it might be rabid, he found it to be in good health but its stomach was filled with frozen grapes.

Mixed Up BirdsWASHINGTON . . . The auto racing reporter for the Washington Daily News was asked where it was possible to buy a hood for a Falcon. He named a number of car dealers before the caller interrupted with, "No, my falcon is a hunting bird."

Give It BackNEW MEXICO . . . After listening all day to a debate on what to do with wilderness land at a public meeting in Albuquerque, an elderly Indian suggested, "Give them back to the Indians."

Cash CatchTENNESSEE . . . Fishing pays off. An angler hooked into a cloth-wrapped bundle. Examination disclosed $685 in old paper bank notes dating back to 1902.

DEEP-FREEZE

continued from page 29logs, decaying wood, and other debris often yield a variety of grub baits that can entice a fish or two.

Finally, there are the aquatic larvae and nymphs that can be found in water, often under the ice itself. They include the hellgrammite, May fly, stone fly, and caddis fly. These are all nymphs of larvae forms of aquatic insects and spend their early life underwater. Many of them live in Sand Hills lakes and ponds where they cling to rocks and vegetation on the bottom. With the exception of hellgrammite, most like the quiet offshore waters of ponds and lakes.

When prospecting for these baits, look for bottom growth at depth of 15 to 30 inches. Chop a hole through the ice and use a rake or other device to bring up plants and debris. Spread out the gunk and look for the bait.