OUTDOOR Nebraska

AUGUST 25 cents NEBRASKAland on Stamps Page 8

OUTDOOR Nebraska

Selling Nebraska is your business August 1963 Vol. 41, No. 8 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor J. GREG SMITH, Managing Editor Bob Morris PHOTOGRAPHY: Gene Hornbeck, Lou Ell ART: C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, Frank Holub ADVERTISING MANAGER: Jay Azimzadeh

STING of the Snake

The boiling currents lured us on to our date with crushing windfallTHE WINDFALL whipped out of nowhere. A tangle of branches speared toward us. George Nason yelled a warning, but too late. His hat was slapped from his head as he tried to duck. The paddle ripped from my hands as I jabbed desperately to avoid the tangle. Bob Wood, clawing frantically at empty air, was peeled from the deck and hurled into the boiling current. The aluminum raft jarred to a shuddering, grinding halt in the windfall, and water boiled over the side.

Bob's hands clamped over the transom. Hat gone, face streaming water, he saved himself from the hissing river. Filled with water, the swift current pushing against it, the raft began to tip. George and I scrambled into the windfall, finding safety in the branches, while Bob, chest deep in the water and with his back braced against a rock, hauled at the raft in a vain attempt to free it from the obstruction.

AUGUST, 1963 3

The rushing water peeled the loose floor board from the inside of the raft. It flipped into the main current and shot toward the next windfall a few yards downstream. I saw my hat sucked under by a whirlpool. A package of lunch meat and another of cheese whished by. As I fought my way to an uncertain foothold on the caving bank, I was thinking, "That does it. This time the Snake wins."

Three hours earlier, Jack Morgan, conservation officer from Valentine, had helped us rope the raft down the steep cliff at the foot of Snake Falls. There, on a small sand bar, we had readied for the attempt to raft the estimated twenty-three miles of twisting canyon between the falls and the Snake River's wedding with the Niobrara.

The upper reach of the Snake, down to Snake Falls, is relatively open, with no deep canyons of consequence, and we had heard of it being boated. The current is somewhat swifter than many Nebraska streams, but it offers little challenge. We wanted to try our hand at the faster current and rapids in the canyon below the falls.

Foolishly none of us had familiarized ourselves with the river. Without ever having seen it before, we had accepted as gospel the proposition that you could put in at the falls in the morning and be on the Niobrara that afternoon.

With equal foolishness, I had borrowed the aluminum raft for George and Bob, and a pneumatic life

raft for myself in the belief these would be right for

the rampaging Snake. When I saw the rock studded

AUGUST, 1963

5

runs and the windfall snags, I immediately changed

my mind. The air-bubble raft would be ripped to

shreds within a hundred yards.

runs and the windfall snags, I immediately changed

my mind. The air-bubble raft would be ripped to

shreds within a hundred yards.

"I think the aluminum raft will get us through," Bob opined, as he helped George with a life jacket.

Jack Morgan, with the mooring rope in his hands, was testing the pull of the current on the empty raft. I saw a doubtful look cross his face, although he said nothing. Since I had abandoned the pneumatic raft, it meant the three of us would be riding the aluminum boat. After I had helped pack the stubby rig, I took off downstream to be in position for a photograph when Bob and George began the run.

Walking out ahead I realized the river would not be easy. The current plunged headlong into the narrow canyon at a good 15 mph clip. Trees, creepers, and poison ivy gripped the steep slopes wherever they could gain a hold. Along the stream, trees had lost anchorage and toppled into or across it. Some jammed the tortuous bends completely. A submerged one could rip the guts from anything the current carried over it.

Hanging to vines and trees to keep from sliding

into the river, I felt the spray from the first stretch

of white water where it foamed over some rocks. A

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

stub spanned the stream nearby, so I braced my

back against a tree and waited.

stub spanned the stream nearby, so I braced my

back against a tree and waited.

Above the rush of the water, I heard a faint yell. An instant later the raft shot around the bend, Bob riding the forward deck, paddle fending off the rocks. George sat behind, steering as best he could. The raftsmen ducked the stub when the boat slid under it. Momentarily out of control it sloughed sideways, bumped off a rock, and slid into shore, grounding solidly on a small patch of mud. Bob practically rolled off the deck with the impact.

"Well, we had to stop to pick you up anyhow," he grinned. Then he added, "When you get going on that current, you move."

"I learned more in that five minutes about rafting than I have in a lifetime of reading about it," George said. "It's a thrill, all right."

The three of us stacked into the hull and the Snake grabbed us. Crowded as we were, George had difficulty with control, and when Bob fended off a rock, half his paddle blade split away. I was a useless passenger, unneeded ballast that was only in the way.

George powered toward shore again. A tangle of brush with too narrow an opening to let us through choked the river ahead. Sweating, straining, and stumbling, we fought our way around it, only to be faced with a log barrier a few yards beyond. Waist deep in water, Bob dragged the boat over it. "Man," he gasped, "this stuff is really cold."

Ahead stretched still more windfalls. I caught myself eyeing the cliff walls. For long stretches they lifted straight up from the river, making it impossible to walk the canyon floor. Only occasionally did the stream bed widen out into a tiny meadow of sorts where a landing could be made. If we should have a major accident and injury should occur, evacuation of the victim from the canyon could pose a serious problem.

The next couple of hours were a nightmare. It took many minutes of hard work to circumvent or drag over each of the barriers. We tugged and pulled, slipped and jerked, sweated and swore ourselves to a state of exhaustion, and progressed only 400 yards.

Then, after a particularly tough obstacle, a stretch of clear river showed ahead. The Snake ran turbulently but unhindered around a bend.

"Maybe we're through the mess," George said hopefully, as Bob tossed the nylon towline aboard and we clambered in for what (continued on page 40)

AUGUST, 1963 7

NEBRASKAland on Stamps

It's the biggest selling job yet—a unique opportunity to tell world about NebraskaNEBRASKAland goes on stamps. The spirit of Nebraska's vast historical and cultural heritage, scenic beauty, and outdoor recreation tradition have been captured in 21 colorful tourist stamps created and published by the Game Commission. Now every Nebraskan has the unique opportunity of telling the state's vacation story to the nation and the world. He has the chance of being a vital part of the biggest job of selling Nebraska has yet undertaken.

Scheduled to go on sale in retail stores throughout the state on August 5, NEBRASKAland tourist stamps are the end result of months of planning and research by the information and tourism division. Used on envelopes, stationery, gift packages, etc., the stamps are a positive statement, on the part of the sender, of his support in selling NEBRASKAland.

Tourist stamps will not only provide everyone an opportunity of personally selling Nebraska, but will also be an important source of revenue for the state's tourist program. With money collected from their sale, the Game Commission can carry out vital programs in tourism that have been shelved in the past because necessary funds were not available. An expanded campaign to publicize the many tourist attractions through national advertising, full-color brochures, travel show participation, and expanded tourist-station activity are only a few of the projects that will come closer to reality with stamp earnings.

The original idea for NEBRASKAland stamps can be credited to Senator LeRoy Bahensky of St. Paul. His LB-784 authorized the Game Commission to publish and distribute tourist stamps. The Legislature wasted little time in approving the bill. Then came the long hours of planning in order to execute Bahensky's imaginative scheme.

Each 21-stamp sheet features a balanced combination of history, scenery, culture, and outdoor recreation. Every corner of the state comes in for special attention. Final selection for the 1963 and 1964 offerings was difficult because of the variety of attractions.

The Game Commission has been working closely with Chambers of Commerce throughout Nebraska to assure state-wide distribution. Thanks to their co-operation, NEBRASKAland stamps will be available at a variety of merchants in Nebraska on August 5. Every retailer has been given a sign to designate his store as a distributor. "Look for the store with the sign on the door," as the slogan says, and you'll become a vital part of the Game Commission's biggest tourist venture yet.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 9

Playground IN THE SKY

JOE BEANS was in trouble the moment he stepped from the small Cessna 172. He'd pulled the rip cord too soon, and now, looking up, he had the shock of his life. Instead of a billowing chute, Vic Burrell's booted feet stared him in the face. His partner was hanging helplessly between him and his half-opened parachute. This was an experience all sky divers dreaded.

The pair had gone out at 4,500 feet just seconds

before. The Fourth of July crowd at Capitol Beach

in Lincoln was expecting to see the two sky divers

floating down together. But this was different.

They weren't just together. Burrell and Beans were

10

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

snared in a giant spider's web and the ground was

rushing up to greet them.

snared in a giant spider's web and the ground was

rushing up to greet them.

Fortunately, Burrell was a sky diver of long experience. Instead of panicking, he yanked his rip cord. Once his chute had opened, Burrell fought his way out of the tangle. But Beans was still in trouble. The collision and Burrell's furious thrashing had torn a number of panels from his chute.

Sky divers remove parts of panels to control their descent and enable them to hit the target. But too many were gone to keep Beans' canopy inflated. The chute finally blossomed out but the rush of air through the ragged panels collapsed it again. The chute alternately caught and then failed.

The ground was getting closer. Beans was down to 2,000 feet, 200 below the minimum altitude prescribed by the Parachute Club of America. But the veteran sky diver could care less about such figures at this point. He was more interested in staying alive.

He pulled the cord on his reserve chute, but as it came out of the harness it tangled with the now-useless main canopy. The two spun together, twisting into one gigantic tangle. Most of the crowd thought Beans' plight was part of the act. Only a few, including his wife, Lavon, knew of the life-and-death struggle going on overhead.

By this time the crowd was more than a sea

of ants. Faces were coming into sharper focus as

Beans plummeted toward the ground. Frantically

fighting the two chutes, the sweat coming not just

from the 90° temperature, Beans finally freed his

reserve chute and it partially opened, checking his

descent. It was enough, he knew, to get him down

AUGUST, 1963

11

alive, but not slow enough to stave off a stay in the

hospital. But that was better than nothing.

alive, but not slow enough to stave off a stay in the

hospital. But that was better than nothing.

With his life assured at last he went to work methodically untangling the twisted lines. Finally at 200 feet his reserve chute blossomed out, stopping the sky diver's death plunge at the last possible moment.

Relating the experience later, Beans was asked why he's a sky diver. "It's the best relaxation I can find," he answered. Obviously this is the kind of relaxation most would do without. But the 37-year-old father of six had his reasons.

"You can get in a jam in most any other sport. If you give up everything that could kill you, you'll end up hiding in the cellar."

Beans is past president of the Black Hawk Sky

Divers of Lincoln, the largest of three such clubs in

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the state. Most of the 29 members of the Black

Hawks are in their early 20's with but just a fraction

having Bean's experience.

the state. Most of the 29 members of the Black

Hawks are in their early 20's with but just a fraction

having Bean's experience.

Although sky divers trace their sport back to 1495 when Leonardo da Vinci designed a pyramid-type parachute, it wasn't until 1919 when the first free fall was made by Leslie Irvin, an American. In the early 1930's the sport, as it is known today, began when a group of Russian factory workers participated in a sports festival to see who could land closest to a target. In 1949 French parachutists refined free and delayed fall techniques.

Many sky divers also participate in skin diving. In both cases, the diver defies nature by invading areas he was not intended to roam.

The sky diver has found that by altering the position of his body while falling through space he can perform rolls, back flips, figure 8's, and other tricks before opening the parachute. A body falling in a spread eagle position will reach a maximum speed of 120 miles per hour. By moving the arms and legs close to the body, this speed can be doubled. And if you bend the body from the waist it is possible to turn while in flight.

Typical of the Black Hawks is 23-year-old Dick Headley. The well-muscled 155-pounder is a graduate of Lincoln High where he starred on the gymnastic team for three years. He has made 40 jumps since he began diving in 1961. Headley worked his way up from a student jumper. As a student he used a static line to release his chute. Now he makes delayed falls of up to 40 seconds. Headley finds he can do everything in the air he could do in gymnastics, but the chutist has more (continued on page 36)

AUGUST, 1963 13

BONUS HUNT

Every fall King Pheasant takes over as $1,000,000-plus cash cropTHE FOUR men pulled into Anywhere, Nebraska,

late on Friday afternoon, the day before the

opening of the pheasant season. Their 800-mile

trip from Ohio had left them tired and hungry and

they were anxious to check in at a motel and get

some grub. After getting cleaned up, the quartet

headed for the restaurant and a hearty meal. Later

the nonresidents bought their permits, picked up a

couple of boxes of shotgun shells, and filled their

car with gas. Even before they had seen a ringneck,

14

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

they had already dropped a bundle of money—new

money—in Nebraska.

they had already dropped a bundle of money—new

money—in Nebraska.

Day after day throughout the 86-day 1962 pheasant season scenes like this were repeated all over the state. These four were among the 16,038 out-of-state hunters who flocked here to enjoy NEBRASKAland hunting. When they were through, they took home their pheasants, quail, grouse, and other game, and, just as important, left over a million dollars in the till.

Every fall the money pours in, thanks to the pheasant, the state's No. 1 game bird. Nebraska has plenty of pheasants. Even with long seasons and liberal bag limits, local hunters hardly put a dent in the population. If the surplus isn't harvested by sportsmen, it will be taken by natural causes. That's where the nonresident comes in. By encouraging out-of-staters to get in on the pheasant bonanza, Nebraska reaps a rich harvest of the long green.

This isn't a penny ante game. A recent Game Commission survey shows that each nonresident hunter spent, on the average, $62.30 while he was here. Nearly half stayed five or more days. Of every dollar spent, 33 cents went for food, 24 on lodging, nearly a quarter for gas and oil, 9 cents on equipment, and about a dime for miscellaneous items.

Every time the quartet from Ohio spent a buck, a third of it went to the local restaurant. But the cafe owner wasn't the only one to benefit from this bonanza. In addition to his profit there was the extra waitress who worked during the rush period and the food and beverage suppliers who received direct return on this money.

The restaurant owner bought an automatic washer from the local appliance outlet and a set of tires from the auto dealer. The department store sold a new coat to the waitress and she also decided it was a good time to buy that bike her son wanted. A rancher in the Sand Hills found a bigger market for his cattle. After all, dinner means steak and steak means prime Nebraska Herefords. A nearby farmer sold a lot more eggs during the season and an extra hog for bacon-and-egg breakfasts. The motel, service station, and hardware store operators spent their share of the hunting dollar much the same way, the money finally touching every facet of business life in the community.

In addition to the $l,000,000-plus figure spent in this manner, there were other tangible results from these 16,038 out-of-staters. They spent $256,608 in small-game permit fees and stamps. Although non-resident permits accounted for slightly over 10 per cent of the total sold, the money derived from them made up 31 per cent of the Game Commission's income from permit fees. Nonresident big game and fishing permits brought in $67,675 more.

Even the state's Pittman-Robertson federal-aid funds get an assist from nonresident hunters. Money allocated to each state for wildlife restoration projects are based, in part, on the number of individual hunters purchasing permits. Every nonresident who comes to Nebraska boosts this figure.

But nonresidents do more than just spend money. Last year they took home, on the average, 11 pheasants, 5 quail, and 1 grouse. This is slightly better than residents did on pheasants and about the same as on quail and grouse. The visitors are pretty good hunters, too. The report shows 95 per cent were successful in bagging pheasants and 32 per cent on quail.

Where did they hunt? All over, although 37 per cent of those surveyed found the area bounded by the Kansas line on the south, the Platte River on the north, and from the Colorado border east to Hastings to their liking. Next in popularity was the region bounded by Hastings on the west, Crete on the east, and running from the Kansas line north to South Dakota. The counties of Custer, Dawson, Buffalo, Hall, Howard, Sherman, Valley, and Greeley played host to 15 per cent of the visitors.

As expected, quail hunters had the best luck in the southeast corner of the state. They bagged an average of 17 birds per man, although only 9 per cent hunted there. Another area showing a high hunter-success ratio was the panhandle, with out-of-staters bagging 12 pheasants each.

In many game-poor states nonresidents are unwelcome guests with severe restrictions imposed to discourage them. But in NEBRASKAland where game is in bountiful supply, out-of-state hunters are welcome. Nonresidents like Nebraska's brand of hunting and hospitality. The vast majority of those contacted in the report say they'll be back again.

Thanks to NEBRASKAland's hunting bonanza, fresh new dollars are pouring in to give the economy a real shot in the arm. Sportsmen, doctor, lawyer, merchant, chief—all benefit from this abundance of game resources.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 15

OUTDOOR Nebraska proudly presents wonderful world of butterflies

a unique nature close-up by Gene Hornbeck and Lou Ell

PRAIRIE DOG PLINKING

THE DOGS paid little attention to the dusty trail of Jim Satra?s car as we moved into their town, 10 miles northwest of Valentine. Sentries on the outer mounds had kept us under close observation, however, and once Jim eased the car to a stop, they barked a warning to the rest of the prairie dogs to go below.

But Jim was in no hurry. With our help, he

stretched a blanket out for us to lie on, positioned

a trio of sandbags out in front for rifle rests, and

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

finally motioned Bill Rhodes and me to move in on

the firing line.

finally motioned Bill Rhodes and me to move in on

the firing line.

Our targets were a hundred yards away. Though they had shown signs of spooking when we drove up, the curious critters were now back to the normal doings of dog town.

The noon sun beat down on my back as I sighted through the 10X scope on a sentry on the near edge of the town. Once the cross hairs settled on his middle, I squeezed off a shot from the bolt-action .222. The impact of the high-speed slug bowled the rodent over and I quickly searched out another target as Bill and Jim opened fire. The action was fast and furious for a few minutes, then the prairie dogs scattered.

This was my introduction to varmint hunting,

Western style. Jim and Bill, both of Valentine, had

AUGUST, 1963

25

offered to show me some of their favorite shooting

spots. I had seen prairie dogs in parks and wondered

why anyone would want to shoot them. No one eats

prairie dogs. They did not seem to offer much of a

challenge to the hunter, either. But that is in parks.

In the wide-open range of the Sand Hills it is

something else.

offered to show me some of their favorite shooting

spots. I had seen prairie dogs in parks and wondered

why anyone would want to shoot them. No one eats

prairie dogs. They did not seem to offer much of a

challenge to the hunter, either. But that is in parks.

In the wide-open range of the Sand Hills it is

something else.

It's not hard to find good prairie dog range in the Sand Hills. The critters congregate in open pasture and there's plenty of that in the 20,000-square-mile area. Mounds of dirt surrounding their dens can be seen from a great distance. In areas where they've been hunted, the dogs are extremely wary. Those we hunted had been educated, thanks to Jim, Bill, and many others who recognize the sport the rodents can offer.

I soon learned that prairie dogs are much like a group of squirrels flushed deep in the woods. Sometimes they hesitate for a split second at the den's opening, offering a chance for fast shooting. When they dive for the holes, the hunter has to either move on to another suburb of dog town or lie prone on a blanket and take a steady rest for the long shots when the critters come out again.

Often there is only a bit of the dog's head showing. Sometimes it is a head-on shot that is just as difficult. At distances greater than 100 yards, either shot calls for precision shooting. Even Jim and Bill, old hands at this game, missed their share of shots.

The .222 is Jim's favorite varmint rifle. "I fire between 800 and 900 rounds per year through that 26-inch barrel," he said. "A 50-grain semi-point or Hornady SL bullet backed by 22% grains of powder is my favorite load. It's extremely accurate and has less noise and recoil than some other loads. A 2 1/2-pound-pull trigger lets me squeeze off a steady shot."

Jim has made a special .25-06 rifle for long-range shooting. He had it action barreled and chambered by Bliss Titus of Utah. A 2% x 9 variable scope gives him all the magnification he needs. Sporting a 26-inch semi-target barrel, the gun weighs only nine-and-a-half pounds.

One weapon in Jim's arsenal looks out of place on a prairie dog hunt. It's an FN Mauser barreled-action .300 Magnum with a fiddle-back maple stock. This beautiful gun is a big-game rifle used mainly for elk and deer shooting.

"I take the .300 out to a prairie dog town for a little pre-season practice," Jim said. "I use a 125-grain bullet for varmints and a 180-grain slug for elk. The gun has a 4 1/2-pound-pull trigger."

Bill brought only one gun, a .264 Winchester with a three-pound-pull trigger. He used a 120-grain bullet backed with 64V2 grains of 4831 powder. Both men load their own.

"Taking game with a bullet you loaded yourself is half the fun," Jim said. "Hand loading insures a higher degree of accuracy. It's less expensive, too. A box of these .222 cartridges would cost me $2.60.

I had admired the guns on the trip out, and now respected their abilities on the small targets. While we were waiting for another dog to show his head, Jim filled me in on the finer arts of prairie dog hunting.

According to him, the best time to hunt is any day that the temperature is over 50 degrees. Hunting's best when there is no wind, since this keeps the dogs down and stirs up the sand.

We pulled into one dog town shortly after noon. All the mounds appeared to be empty. There was no sign of life, only the sound of a steady cooling breeze blowing over the Sand Hills.

"These dogs have been poisoned out," Jim remarked. "If the trend keeps up, there won't be any dogs to hunt in a few years. Poison will wipe out an entire town in short order. Sharpshooters could hunt a town for years and not kill all the dogs. Hunting just takes the surplus and helps to keep the critters from spreading."

Jim and the rest of the prairie dog-shooting enthusiasts are all for controlling the rodent. Holes are a hazard to cattle and big uncontrolled towns impair the range. But Jim doesn't believe poison should be used. It can wipe out an entire town and ultimately make the dogs extinct in Nebraska. Hunting takes care of the surplus without eliminating the entire colony. As far as Jim is concerned, a gun is far more humane and offers another form of sport.

That day we must have taken at least 40 dogs from various towns around Valentine. My introduction to varmint hunting was a tremendous success. It's the kind of sport that sharpens your eye while offering plenty of relaxing fun. I, for one, hope that there will always be dogs around to plink at, and as far as that goes, to see and enjoy.

THE END 26 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

INDIAN CAVE a park in the making

Rugged bluffs of the Missouri are setting for latest recreation boom Massive interior of overhanging cave has history dating back many centuriesIT WAS DARK inside the overhanging cave perched high above the Missouri. In the half-light that filtered through the tangled opening the outlaw didn't notice the strange drawings around him. Later, slumped in a corner and bone-tired from his all-day race with the posse, he began making out the weird figures by the wavering light of his campfire.

There was a fish-like form with what appeared to

be a three-toed leg extending from each side. Crude

human figures mingled with those of animals on the

sandstone walls. What other men had used this

cave before him? Where had they come from and

where did they go? He fell into an exhausted sleep,

AUGUST, 1963

27

caring not for the past, worrying more whether the

morning would find him swinging from a tree.

caring not for the past, worrying more whether the

morning would find him swinging from a tree.

In earlier years, so the legend goes, John Brown hid escaped slaves in the same cave overlooking the winding Missouri. And rumor has it that members of Quantrill's gang stayed here. Fresh from the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, they were preparing for a similar raid on Nebraska City, 34 miles upriver. Hidden as it is in the towering bluffs, this cave made an ideal hideout for bad and good guy alike.

Today a transformation is in the making. Modern roads will replace the tortuous trails as picknickers follow the footsteps of outlaws. Families will spend their vacations in modern cabins where Indians, in centuries past, erected their tepees.

Indian Cave State Park, the newest and largest in the state, will soon arise from this link with the past. Astride the Richardson and Nemaha county lines, this 4,200-acre treasure of history is a breakthrough in NEBRASKAland recreation. Nearly as large as the other four state parks combined, Indian Cave is a giant step forward.

Estimated cost of turning this timbered wilderness into a fun-filled mecca will be $1,000,000, the

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

funds coming from the 10-year park program. A bill

passed in the current session of the Legislature giving the Game Commission the right to acquire

private land for public use has played a major part

in making this area possible.

funds coming from the 10-year park program. A bill

passed in the current session of the Legislature giving the Game Commission the right to acquire

private land for public use has played a major part

in making this area possible.

The first work on the park will begin late this fall or early in 1964. In addition to the natural and historical values found there now, a swimming pool, cabins, bridle paths for rental horses, and picnic accommodations are to be built throughout the heavily-timbered park. Boating and fishing facilities will round out this prime recreation area.

Indian Cave will be a windfall for eastern Nebraska residents. It is within a three-hour drive of 55 per cent of the state's population. The park site is located in an isolated area, and, at present, there are only a few seldom-used trails leading from the flatlands to the east. The first order of business will be construction of access roads. Tentatively a road or roads leading to the area will be built by either or both Richardson and Nemaha counties.

The cave is the primary attraction. Claimed to be the largest Indian art gallery in the state, it has etchings on its walls dating back to prehistoric times. In addition to human and animal figures, there are designs thought to have religious significance to early man.

Another feature of the park is the long-deserted village of St. Deroin. Founded in 1854 by an Otoe Indian, Joseph Deroin, this river-boat center was supposed to have been one of the earliest towns in the Nebraska Territory. As railroads took over in importance, St. Deroin became a ghost town and all but disappeared into the Missouri in 1911 when the rampaging river changed its course.

The area is crescent-shaped, its eastern border formed by the twisting Missouri. Indian Cave is located on the eastern-most part of the area. St. Deroin is at the northern point. Towering bluffs rise abruptly from the river, becoming tree-studded valleys and canyons to the west and south.

A botanical and geological puzzle, the area has vegetation normally found in northwest Tennessee. It is studded with sandstone bluffs found nowhere else in the Midlands.

By combining the rugged naturalness of this historic area with modern improvements, Indian Cave State Park will in the future become a show place for the state. Prehistoric Indian remains and modern camping rigs, hangout for outlaws of old and a favorite picnic spot for families, yesterday's ghost town and today's busy swimming pool—all will blend in a setting that will be hard to match.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 29

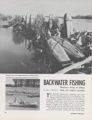

BACKWATER FISHING

Missouri's string of hidden lakes are angler s paradise by Gene HornbeckTHE 20-FOOT flatbottom skimmed upstream over the swirling currents of the Missouri. The Decatur Marina faded away in the distance, as Jack Maryott opened the throttle on the 75-horse outboard. Jack's sons, John and Jim, were aboard and scanned the river ahead, eager to tie into the variety of game fish waiting in one of the many ponds formed with the rechanneling of the river.

This father-and-son combo had been fishing these

small areas for years. During the past month they

30

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

had been catching huge crappie, some weighing

nearly two pounds. Sauger and bass had also come

their way with satisfying regularity.

had been catching huge crappie, some weighing

nearly two pounds. Sauger and bass had also come

their way with satisfying regularity.

Jack swung the beamy craft into the shore just above a stream-control structure. Jim hopped ashore, throwing a quick hitch on one of the pilings to secure the boat. Waiting beyond the pilings was a small pond, once a bend in the river. The trio had fished this one before and knew it produced nice crappie. It and countless other lakes are found up and down the river.

The elder Maryott rigged two fly rods with light corks about three feet above a No. 6 hook, pinched on a small split shot, hooked on a lively minnow, and swung the rig out into the water. John and Jim followed suit.

Less than a minute passed before John's cork danced nervously on the surface and then plummeted out of sight in the discolored water. Reefing back, he set the hook on a 10-inch crappie. Corks began disappearing with regularity as a good school accepted the trio's minnow offerings. An hour later Jim and his boys had 25 nice crappie. When the school quit feeding, they loaded their stringers aboard and headed upstream to another of the many cutoffs.

The next stop was a larger area. A series of deflectors along the Iowa shore had formed four fair-sized ponds. Jim took his boat roaring in over the muddy shallows at the entrance to one and tied up along one of the rocky reflectors. Largemouth bass and crappie often frequent the rock fill and the trio once again set their hooks in a nice run of crappie.

This was a typical day along the river for the Maryotts. As the summer wore on, the father-and-son team worked the cutoffs for catfish. Largemouth, walleye, and sauger hit well in the twilight hours, and close to a half dozen other species added to their angling fun. Drum, carp, mooneye, white bass, and even gar offer many pleasant fishing experiences.

These cutoff ponds range from small ponds or pools to large lakes. Many of them have been here for years and are not heavily affected by silt. One of the largest is the DeSoto Bend Refuge south of Blair. From this area upstream, scores of small ponds lie ready and waiting to be fished. DeSoto Bend came in as a good producer on crappie, and this spring walleye, catfish, sauger, and largemouth were taken with regularity.

Some lakes are 12 feet deep or more. Others run only two or three feet, but attract many species of game fish, especially during the early morning and evening hours when they move in to feed.

Fishing and boating regulations on the Missouri are reciprocal with Iowa. The fisherman or boater must comply to the regulations of the state in which he holds his license. The agreement allows the fisherman or boater to enter or leave from either shore. License holders from either state can fish any waters of the Missouri River, including oxbows, cutoffs, and sloughs, so long as these areas are connected with the Missouri River proper. This does not include tributaries of the Missouri, however.

The agreement with South Dakota allows fishermen to enter or leave from the shore in which they hold a current license, meanwhile complying to the regulations of that state. When fishermen find it necessary to travel in the neighboring state going to or from the Missouri River waters, they are permitted to transport their fish to their residence, providing that they do so by the most direct route.

Take it from the Maryott's, these out-of-the-way places pay off in top-notch fishing. Head for the big waters, pick your pond, and start reeling the gamesters in.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 31

WILDERNESS COMFORT

A few extra minutes can make the difference in a good night's sleepTHE MERE USE of a sleeping bag in camp will not guarantee comfortable slumber, although most tyro campers believe it will. The foundation you build for it is the real key.

First, make sure you select a level site. On even a gentle slope, in the relaxation of sleep, you will slip several feet during the night. Just as important, remove all sticks, stones, and other lumpy foreign matter. If you sleep all night on a marble-sized pebble, it will grow to baseball proportions before morning.

Ground moisture is present even in the driest

places. Unless your sleeping bag is isolated from it,

the bag's insulation absorbs this moisture, and its

warmth-retaining ability is lowered considerably. To

seal out moisture, stretch a ground cloth over the

32

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

cleared area. A piece of plastic sheeting, oil cloth, or

an old shower curtain works well. Ordinary canvas,

however waterproofed, is a poor choice.

cleared area. A piece of plastic sheeting, oil cloth, or

an old shower curtain works well. Ordinary canvas,

however waterproofed, is a poor choice.

If you're young and rugged, you can throw your "sack" directly on the ground cloth, and manage to sleep. However, most people prefer a softer bed, so the next part of the foundation may well be an air mattress.

A cheap, plastic mattress may serve for an occasional night or two in the open, but don't be surprised if it goes flat the first time you use it. Satisfactory repair is impossible. Mattresses of rubber-coated cloth, either cotton or nylon, usually wear well. Most veterans prefer "waffle" or "quilted" construction to the conventional tube-type mattress. Either support you as comfortably as your mattress at home.

Inflate the mattress just enough so that, when you lie on it and turn over, your hips and shoulder touch the ground during the shift. Lying still, you should only sense the ground at these points. With level earth, ground cloth, air mattress, and sleeping bag, you'll get along well in mild temperatures, sleeping either in a tent or under the stars.

In spring or fall, when temperatures drop into the 40° range, you may wake up feeling chilly in different parts of your body. Your weight naturally compresses the filler of the sleeping bag until no thickness is left to insulate you from the cold air in the mattress. Every time you move, air in the mattress pumps around, bleeding more warmth from your body at the points of contact.

To remedy the cold, use more insulation between you and the pad of cold air. A folded woolen blanket between mattress and sack works great. If you are going light and a blanket is not available, an inch or two of dry straw, grass, or leaves on top of the mattress and covered with a fold of the ground cloth serves the same purpose.

At big-game hunting time, the temperature may skid to freezing and below. Your sleeping foundation changes accordingly. Spread out the ground cloth. Pile an even layer of dry hay, grass, straw, or leaves to a depth of at least six inches or more on half the cloth. Fold the other half of the cloth over it. If the ground cloth has grommets or snaps, fasten the top and bottom edges together so the insulation cannot spread. If you are allergic to these materials, or they are not available, blanket-type home insulation like that in tough paper makes an excellent foundation. A stack of two or more strips about six feet long not only insulates you from frigid ground cold, but forms a resilient cushion for comfortable sleep. If you need a slightly softer bed, place a nearly deflated air mattress under the stack, but don't nullify the insulation by using too much air. Generally speaking, air mattresses are for more mild weather and have little place in a winter bivouac.

Any of these padding ideas apply equally to a blanket roll of course. So, next time you sleep out, try it the right way, and see how much better your rest can be.

THE END

WHERE TO GO

LOUISVILLE

Fishing, picnics, and camping features hereARE YOU LOOKING for a spot where your chances of catching k lunker bass are good? How about a spot that is also ideal for a family outing? One state area offers all this plus the advantage of being within less than one hour's drive of Nebraska's largest cities. This is the Louisville Lakes Recreation Area, a spot that has a lot to offer the outdoor family from the city.

Four sand-pit lakes serve up bass, bluegill, crappie, catfish, and carp fishing. Largemouth bass are found in three of the lakes with Lake No. 2 the top producer. A put-and-take lake is stocked regularly with carp and bluegill, crappie, and a few catfish are found in all lakes.

Fisheries technicians rate Louisville Lakes as self-supporting. This means there is natural fish reproduction and additional stocking is not necessary. In fact, there have been too many fish at times. Pike were introduced this spring to help control some of the surplus bluegills in one lake. In addition to keeping the panfish in check, the husky battlers provide plenty of sport.

Park roads lead right down to the

banks of the Platte. Hundreds of carp

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

swarm into the river's shallows to

spawn, offering bow fishermen plenty

of fast action. Catfishermen can also

bring in nice creels along the river.

swarm into the river's shallows to

spawn, offering bow fishermen plenty

of fast action. Catfishermen can also

bring in nice creels along the river.

In the past, the Platte has left its bed to meander over the park. In addition to causing damage to park facilities, the floods have sometimes left undesirable rough fish in the lakes. A new dike built by the Game Commission should help prevent this situation in the future.

The family man who likes to fish will find plenty of facilities to entertain his wife and children. Kids can have a ball on the playground equipment or swim in one of the lakes. Caution should be used, however, since there are no lifeguards at the park. Boats without motors can be utilized for fishing or leisurely rides across the lakes.

Louisville is an ideal place for a cook out. The Game Commission has provided handy fireplaces and the wood is already cut and waiting. Picnic tables are found throughout the area. The angler out for a week-end trip can pitch his tent or park a trailer under the many trees growing by the lakes. Facilities include toilets and drinking water. The spacious park covers one hundred ninty-two acres. The four lakes cover 50 acres.

During the fall, the area around the park offers good hunting. Pheasants are found on nearby farm land. Small-game hunters can also cash in on rabbits and squirrels in the wooded hills with deer and waterfowl as added bonuses.

This area is a prime example of what can be done with land that would otherwise be wasted. Lakes at Louisville are the result of commercial sand-mining operations. The Game Commission took the land and developed it as a much-needed recreation area. A real face lifting is in store, thanks to the Game Commission's 10-year improvement plan. Running water, improved toilets, and paved roads will be added as well as a camping area away from the picnic grounds. Too, a swimming area will be laid out on one lake.

Add up Louisville Lake's advantages, then consider its future. Varied fishing, a good spot for picnicking and camping, assured hunting access, and a fine place for family recreation next to Nebraska's population center make it an important part of the state's recreation future.

THE END

PLAYGROUND SKY

(continued from page 13)time to perform each maneuver. In one instance he did seven back flips in 20 seconds.

"It's an exciting sport," Headley says, "but it's hardly one where you can afford to take chances. While you're doing various maneuvers you have to keep a close watch on your altimeter and stop watch strapped to your chest. You always hear of the dangers involved, but club members have only suffered one sprained ankle in 1,500 jumps in the last 3V2 years. This isn't a sport for the timid but the reckless daredevil isn't wanted either."

According to Headley there is little sensation of falling in sky diving. Instead it appears that everything but the diver is moving. The plane, after you jump, seems to float upward slowly. The ground gradually becomes closer. There is a relaxing, floating sensation as if you are balanced on air.

"You can do anything a plane can do except go back up," explains Headley. "A diver can float on his back or stomach. There's a feeling of freedom nothing else approaches. By altering the position of your body to control your speed and steering with your hands, it's possible to float right up to another diver. Divers can chase each other through the sky twisting and turning as two planes would in a dog fight."

Once the sky diver reaches 2,200 feet and the parachute opens, the next phase of sky diving begins. The 28-foot parachute slows the diver down to about 16 feet per second. Then the sky diver guides his specially slotted chute to a target.

Popularity in sky diving is growing by leaps and bounds. In 1961 there were an estimated 2,000 in the country. By last year that number grew to an estimated 25,000. There is still plenty of room for everyone, especially in Nebraska's wide-open skies. The Black Hawks and other divers will be glad to have you aboard.

THE END

Go ahead, make yourself at home. Motels offer you so much more in the way of fine accommodations.

After the day's shooting is over, look for your nearest motel. It will give you the best in service. Your bath is hot and ready, your bed is all made and clean. Many motels offer you food service, or a fine restaurant is only steps away.

Your motel manager is ready to give you valuable tips about where the shooting is best, where you can obtain your hunting supplies, or make arrangements for guide service.

Make yourself at home . . . stay in a motel. Make the motel your hunting headquarters. Where you are always welcome.

NEBRASKA MOTEL ASSOCIATION ERIN-RANCHO Motel Finest in Grand Island The best in lodging The best \n hospitality The best in service The best in location 2114 West 2nd Street GRAND ISLAND THUNDERBIRD MOTELS Sey-Crest Motel Highway 275, Norfolk Pawnee Motel Highway 30 & 81, Columbus Country House Motel 115th & West Dodge, Omaha Goldrenrod Motel Highway 81, Geneva Redwood Motel Highway 6, Hastings Westward Ho Motel Highway 26, Scottsbluff Fort Sidney Motor Motel Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge Best Western and AAA SIDNEY, NEBRASKA Lee's Motel Highway 30 Lexington McCoy Motel Highway 6 Arapaho Hammer Motel Highway 30 Kearney Rambler Court Motel, Highway 30 North Platte Buck-A-Roo Motel Highway 81 Norfolk Cedar Motel Highway 20 Randolph Skyline Motel Phone 2711 Spencer Blair House Motel Highway 30 Blair Travel Lodge Motel 507 West 2nd Grand Island Chief Motel McCook Cedar Motel McCook Frontier Motel Alliance Rose-Ed Motel Norfolk Star Motel Highway 33, Crete Crawford Motel Central City

IN THE DEVILS NEST

by Francis Moul Following in the footsteps of the cowpokes is adventure-filled rideWOOD WAS piled high on the smoldering campfire. Huge coffee pots and skillets clattered as drowsy forms, wrapped in blankets and using saddles as pillows, started to stir about in the crisp dawn air. The sun was just beginning to blossom out over the top of the rolling hills, heralding what turned out to be a perfect day.

The scene was a campsite deep in the Devils Nest area near the Missouri River. The rolling range provided the setting as we sat down to breakfast before leaving on the 20-mile circle to the shore of Lewis and Clark Lake. Television, electric can openers, and all the other modern-day conveniences were forgotten as the 25 riders, ranging in age from 11 to 71, readied for the adventure-filled day.

All were members of the Dixota Wranglers of South Sioux City. The group sponsored the ride and the 18 club members met with other riders from nearby towns to complete the group. The weather was perfect and the horses as eager as their riders. Don Arrens, owner of Acorn ranch, supplied the campsite and scenery.

Cars and trucks brought the riders to the starting point, 20 miles from Crofton the night before. The every-day world was soon forgotten as real horse-power became the only means of transportation. Saturday evening was spent with a short eight-mile ride from camp to view the startling scenery through the rays of the setting sun.

The western flavor was captured over a supper of

modern-day hot dogs followed by square dancing

and folk songs around the crackling fire. Saddles

became pillows for hardy cowpokes who slept out

in the chilly star-filled night. The horses were fed,

38

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

watered, and brushed down. As the rest of the camp

slumbered, a watch to keep the horses quiet and

guard against a prairie fire was set up.

watered, and brushed down. As the rest of the camp

slumbered, a watch to keep the horses quiet and

guard against a prairie fire was set up.

In the morning the group rolled out of the sack, washed up, and got set for a rib-sticking breakfast of pancakes, eggs, and bacon. The grub tasted better from being cooked over an open fire, even if a few ashes did get mixed in for flavor. Horses were saddled and with a hearty "move 'em out" the main 20-mile ride began.

On the trail, greenhorns looked for "heifer bulls" and counted the horse tracks to find their way to camp. A mid-morning break came when the group crossed a cooling shallow stream. Even the sound of the water was a relief to dry throats. Riders and horses shared the refreshing water side by side. Then it was back to the trail. Out in this country, pardner, the wheat grass is knee-deep to a horse and buck brush abounds. Here deer roam and cattle by the thousands dot the hillsides.

Old-timers on the ride told of the time a couple of cowboys who met the Devil late one night. They were riding home from an evening at the local casino and were feeling kind of wild. They roped old Satan after a terrific fight and trussed him up to a scrub pine tree. Then, just for fun, they notched the Devil's ears, clipped his horns, and put a knot in his tail. They treated the Old Devil so bad that even now, if you listen hard enough about midnight, you can hear him howling out on the range.

This lonely rangeland will see the results of a startling change in the next few years. Nebraska businessmen are planning a modern year-round resort at Devils Nest along the shores of Lewis and Clark Lake.

OUTDOOR Nebraska proudly presents the stories of its readers themselves. Here is the opportunity so many have requested—a chance to tell their own outdoor tales. Hunting trips, the ''big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor impressions—all have a place here. If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, OUTDOOR Nebraska, State Capitol, Lincoln 9. Send photographs, too, if any are available.Rugged bluffs and twisting canyons framed the huge impoundment. Spotted along its miles-long surface were scores of boats, their riders out for a day of fun. The Dixotas took a long look-see at Lewis and Clark. But once lunch was over, it was time to head back.

The cooling afternoon breeze greeted the riders as they made their way back to camp. It had been a long day and hard on soft muscles—but one no one would soon forget as they rode through the breath-taking beauty of the Old West. Only the sky-high trail of a jet-age plane reminded the Dixotas that they would soon be back to the everyday world.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 39

STING OF SNAKE

(continued from page 7)seemed the hundredth time. My tiredness was forgotten momentarily as I tasted the exhiliration of a free run. With a whoop, Bob dug his broken paddle deep into the water and the close pressing canyon walls swept by in a flash as the boat surpassed the speed of the current. It seemed we were in control of the situation.

"Take the bend on the inside," Bob yelled over his shoulder.

We swung around the sharp curve, and it happened. The windfall whipped out of nowhere, and George's "look out" did nothing to save us.

Later we wrestled the boat onto the steep bank and checked it over. It had withstood the ordeal remarkably well. There were several big dents and a couple of popped rivets where the tremendous pressure of the water had held it unyieldingly upended against the last obstacle, but its seaworthiness seemed unimpaired. We had but two paddles left, however, and our food, drink, and other equipment was tearing along somewhere in the current of the Snake.

I began climbing the almost vertical cliff face.

"Where are you going?" Bob asked.

"I'm scouting the next mile of this blasted river," I said. "Before we go another foot, I want to see what lies ahead."

"Good idea," George admitted. "We should have done it to begin with."

I felt like a mountain climber when

I finally gained the ponderosa-trimmed

rim. I rested for a moment, and heard

other movement. Bob had climbed up

after me. We followed the twisting

canyon, studying the silver ribbon below. From the rim, the Snake looked

far from the formidable thing we now

knew it was. Based on our experience

40

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of the last few hours, we counted 12

sizeable barriers in that mile, and a

number of lesser ones.

of the last few hours, we counted 12

sizeable barriers in that mile, and a

number of lesser ones.

Bob looked at me. "Two days," he said. "If it's all like this, it's two days of hard work to the Niobrara. Even if we beat down all the barriers, the old Snake itself might not let us live that long."

We rejoined George where he waited by the boat, and reported our findings. After some serious discussion, we voted to call it quits. It was hard work getting the boat out of the canyon, but with George and I pushing and Bob hauling, it was done.

I looked down at the river. "You'd better keep the sting in your tail, Snake," I told it. "You're tough, but you can be whipped, and I'm coming back to do it."

"If the water is warmer, I'll help," Bob said.

Wisely, George didn't commit himself at all.

But I have. There'll be another battle between the river and me. After adequate groundwork and some real preparation, of course. When it happens, wish me luck.

THE END Be sure to read future big issues of OUTDOOR Nebraska to learn whether Lou Ell or the Snake wins the battle of the white water.—Editor CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS 15 cents a word: minimum order $3 September closing date, August 5 DOGS GERMAN SHORTHAIRS, setters, and pointers for sale. Write for prices and details about the dogs. Donald Sallenbach, M.D., Gibbon, Nebraska. BRITTANY SPANIEL: April pups sired by Yankee Boy's Tommy— 1961 National Champion—other sired by Rocky. All are out of our best hunting females. Rudy Brunkhorst, Columbus, Nebraska. Telephone: 563-0011. AMERICAN WATER SPANIELS: Fine hunters, retrievers. Choice puppies. AKC registered. John Scofield, Jonesburg, Missouri. BRITTANY SPANIELS: Sire, top son of champion Buts' Tic Toe Bobby, dam's mother from champion Jeff of Minnehaha and Rebbecka of Minnehaha. Natural hunters, loyal pals. C. F. Small, Atkinson, Nebraska. AKC LABRADORS: Excellent field trial pedigrees. Few young dogs, some field-champion sired. Four litters for fall delivery, $50 up. Kewanee Retrievers, Valentine, Nebraska. Telephone 26W3. REGISTERED VIZSLA PUPS, Started dogs. Bred females. Stud service from best hunting bloodlines. Frank Engstrom, Grey Eagle, Minnesota. FISHING FOR SALE: (Dissolving three way partnership) One Raytheon Model DPD-100 depth sounder, one new 12-volt battery, one Schauer battery charger, carrying case, all complete. Tells you where the drop off is, depth up to 200 feet, weed beds, etc. Priced and ready to go $130. J. P. Lannan, West Point, Nebraska. RESEARCH PROVES That Fish Have Six Senses. Evaluated knowledge of all six senses is vital to fishermen in their luring efforts. Fish don't reason—they respond to sense-organ stimulus. For authoritative facts, get "Fishtips on the Fish's Six Senses." Send $1 to Fishtips, Department LN, Box 83, Sioux City, Iowa. FISHERMEN: Spinning lure approximately Va oz. Virtually snag proof. Will not twist line. 5(ty each. Jayhawk Lures, 2227 Kenilworth, Topeka 6, Kansas. NEBRASKA HYBRID Red Wigglers for breeding or fishing. 1,000—$4.50. 5,000—$20, post-paid. George Floyd's Hybrid Red Wiggler Farm, 1215 Broadway, Mitchell, Nebraska. GUNS NEW, USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS — Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca, Colt, Ruger, and many others in stock. Buy, sell or trade. Write us or stop in. Also live bait. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, just off U.S. 136, Fairbury, Nebraska. HUNTING CAMPS DEER HUNTING PARADISE, Controlled deer hunting east part of Keya Paha hunting area. Very reasonable rates, selected campsites. and hunting with guide service available. Trailer and tent accommodations at Four Corners Rod and Gun Club Recreation Area. Electricity available. For more information and reservations, write to: Mrs. Manfred Peterson, Secretary, Newport, Nebraska. Telephone 832-5185-Naper, Nebraska. MAKE YOUR RESERVATIONS early for goose shooting. Heated room for two shooters. Write Chet Bishop, Lewellen, Nebraska. MISCELLANEOUS NEBRASKA BRED and reared bobwhite quail and ringneck pheasants—Custom gunstocking. Bourn's Game Farm, Box 275, Overton, Nebraska.

notes on Nebraska fauna...

AMERICAN BITTERN

IF YOU SHOULD see what appears to be either a post or a stump in a marsh suddenly take flight, don't be surprised. The American bittern, Botarus lentiginosis, is a master at concealing himself in marshlands. He has a habit of standing among grass and reeds with his bill cocked up at such an angle that even in full sight he remains unnoticed. The penciled foreneck imitates the reeds and all his colors are inconspicuous. This wary veteran of the marsh has learned the art of moving almost as slow as the minute hand of a clock so as to escape detection while changing positions.

The American bittern, a member of the heron

family Ardeidae, is between 24 and 34 inches long.

Like other members of the heron family, the bittern

has a slender body, long neck, and a long sharp-pointed bill.

The general coloration is brown, blackish, white, and tawny mixed.

The under side is

42

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

yellowish. Unlike the cranes and ibises, the bittern

in flight carries its neck folded and the head drawn

in near the shoulders.

yellowish. Unlike the cranes and ibises, the bittern

in flight carries its neck folded and the head drawn

in near the shoulders.

Unlike many of its close relatives, the herons, who are colony nesters, the bittern is a solitary nester. The female nests in marshes or in wet meadows, placing the nest amidst the cattails, rushes, or other vegetation. The nest itself is a platform usually poorly constructed. In wet meadows, it is often a small hole in the ground lined with vegetation. Materials used include rushes, grasses, small sticks, or similar vegetation. Sometimes the bird makes a path to and from the site, so that she can approach and leave without too much interest on the part of her enemies.

Four or five eggs are layed and are of a buff color, unmarked. The young are hatched in about four weeks, and remain for sometime in the nest. They feed on regurgitated food from adults for much of this period. In the manner of many of the herons, the young takes the bill of the adult crosswise to get their food.

Helpless, homely and awkward, the young are exposed to many dangers in their lowly nest. Mink, muskrats, and water snakes abound in the swamps and marshlands. Keen-sighted hawks, eagles, and owls sweep overhead, posing a constant threat. The watchful mother is ever ready to defend her young and with her dagger-like bill and long neck she is no mean antagonist. When danger threatens her young, she bristles to twice her usual size and with glaring eyes and open beak becomes a dauntless defender.

Food consists almost entirely of animal matter. Bitterns are not particular regarding the kind. They live on frogs, small fish, crayfish, snakes, lizards, mice, mollusks, grasshoppers, and other insects. The bird usually stands in shallow water waiting for some unsuspecting creature to come within reach of his sharp bill.

Some of the common names given the American bittern are stake driver, thunder pumper, mire drum, and bog bull. The common names are derived from the strange call uttered by the bittern. While producing his call, the bird looks like he is trying to rid himself of some distress of the stomach. The resulting melody sounds much like the sucking of an old-fashioned wooden pump when someone tries to raise the water. When calling, the bird suddenly lowers and raises his head and throwing it far forward with a convulsive jerk at the same time opening and shutting the bill with a click. This is repeated a few times, while the bittern seems to be swallowing air. This is succeeded by the pumping noises which are sets of three syllables each resembling "plunk-a-lunk", or as some say "plum pudd'n". The lower neck seems to fill with the air taken in and remains inflated until the call is completed.

There is a peculiar acoustic property about the sound. Its distance and exact location are very hard to determine. The volume seems no greater when close at hand than when it is at a considerable distance. As the distance increases, the sound is no longer heard as three distinct syllables but comes to the ear as a single note closely resembling the driving of a stake from which it gets its name stake driver. The call, although common in spring, usually goes unnoticed due to its resemblance to pumping and stake-driving sounds.

The American bittern is one of the more common heron-like waders of North America. He is a common spring and fall migrant through Nebraska, occasionally stopping to nest in favorable localities. It ranges in the summer over most of the temperate regions in North America, from the southern Canadian provinces southward toward the Gulf. Winter range includes much of the United States south to the West Indies and Central America.

In spite of the protective adaptions of color and stance, it is frequently shot by hunters. Since the flesh is seldom eaten, it is a pity that a bird of real value in controlling insects and aquatic pests should meet such a fate.

THE END AUGUST, 1963 43

GO-GO INDUSTRIES PRESENTS

Americas Newest Concepts in Camping, Boating and TravelGO-GO MAKES THE GOING FUN the year-round, whether you're a boater, skier, camper, or traveler. GO-GO's fine family of unique dual-purpose vacation gear features the versatile HANDY ANDY, the all-in-one boat, camper, and car-top carrier. Incorporating its years-ahead construction concepts are the flashy, deluxe-equipped GO-SKI and the most useable luggage carrier yet developed, LOTTA-LUGGER. Realistically priced yet quality constructed, GO-GO's right for you.

GO-GO PRODUCTS FEATURE many of the basic structural designs of today's aircraft. All-aluminum made, you're assured of maximum strength with minimum weight. Your HANDY ANDY includes a wood deck, oar locks, float seat, canvas cover, and complete tent attachment, all for $199.50*. For those beautiful extras, then GO-SKI is the boat for you at just $299.50*. And before your next trip, see how the LOTTA LUGGER LL-1000 can make the going great for only $69*. Pick the GO-GO that's right for you, then head for a date with fun.

Dealerships available for GO-SKI, HANDY ANDY, and LOTTA LUGGER For colorful folder, write to: GO-GO* INDUSTRIES 1509 Chicago Street, Omaha, Nebraska *AII prices F.O.B. Omaha