OUTDOOR Nebraska

April 1963 25 cents STATE SYMBOLS AMERICAN ELM MEADOWLARK FLAG GOLDENROD SEAL

OUTDOOR Nebraska

April 1963 Vol. 41, No. 4 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. GREG SMITH, managing editor; Bob Morris, Marvin Tye, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard

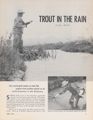

TROUT IN THE RAIN

by Gene HornbeckSPRING HAD come to the Nebraska panhandle country, but the usual rains had not. The grass, lifeline of the cattle industry in Sioux County, struggled to gain growth from the dry soil. Wildlife moved close to the Niobrara and other streams, preying and being preyed on. Trout stayed in the deepest holes, feeling the press of the drought and there was little action.

This is as it was early last May along the Niobrara. Then as if Mother Nature had come to the

APRIL, 1963

3

rescue of her brood, heavy clouds began scudding

across the prairie country. Light rain fell spottily

throughout the parched area, not enough to quench

the thirst of the land, but enough to offer hope.

rescue of her brood, heavy clouds began scudding

across the prairie country. Light rain fell spottily

throughout the parched area, not enough to quench

the thirst of the land, but enough to offer hope.

Lou Ell and I were wistfully watching the overcast sky, waiting for clearing weather. We were at Fort Robinson eager to finish filming the Pine Ridge country around Crawford for the NEBRASKAland movie.

When Park Superintendent John Kurtz and I get together, the conversation just naturally gets around to the art of catching trout. Remembering other rainy days when I'd cashed in on these prized targets, I suggested that John and I give it a try. The streams were coming up a little and with the rain beginning to fall now those big browns down on the Niobrara could be on the prod. John was game, asking only that I wait for him to wrap up his chores at the fort.

Traveling west to Harrison and then south to the Niobrara, we dropped into the river valley. Rain parkas were donned hurriedly, once there. We rigged spinning outfits, popped some minnows into a small bottle, and hiked for the stream. Lou tagged along behind, lugging a flash-rigged camera under all his rain gear. He figured that this would be a contest between John and me. He would stick to taking pictures.

The upper end of the Niobrara is typical of Nebraska's prairie rivers. Tag alder, willow, and cattails lace the banks as the stream twists and turns its way through a valley of grass. The water runs a yard wide and a yard deep at this point. Trout stick in the holes, hide under the grass-covered banks, or wait at the tail of the riffles for a minnow.

Elbowing through a thicket of alder, I eased my way to the bank of the stream. The river slid swiftly by in a straight run into the back eddy of a deep bend 10 feet downstream. The water was slightly discolored, the surface pelted by the falling rain.

John worked a bend a few yards upstream from me with his spinner, as I drifted a minnow into the slide and watched the line melt into the depths of the hole. Mending the line back slowly through the hole, I hoped for a strike. With no action, I began moving upstream. Then John let out a war whoop.

"Hey, Gene, get up here and give me a hand."

Looking up, I saw him walking along the bank as the fish swam downstream toward me at an ever-increasing pace.

"Should go better than 20 inches," John exclaimed, as he kept pressure on the big trout. Water

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

ran down inside his sleeve as he held the rod high

to get it over the alders along the bank.

ran down inside his sleeve as he held the rod high

to get it over the alders along the bank.

I waded in below the trout, ready with my net when the fish tired. Digging the bottom of a deep slide, the brown stayed put for a long minute. John pressured him into action again, this time sending the fish on an upstream surge. The trout cut in close to the bank, passing under some fallen brush to foul John's line.

"Trouble," John called, "he's fouled me up on that brush."

"Feed him all the line you can," I shouted. "Maybe I can get it clear."

Sloshing into the stream, I held the line in one hand to keep it taut while I eased the brush out of the stream. Once clear, I quickly freed the line and told John to take up the slack.

The fish was still on and sulking again on a bend 20 feet upstream from my fishing partner. Five minutes had gone by since John had hooked the lunker and the strain of the battle began to show on the big fish as he rolled to the surface. John stepped into the stream and with a quick scoop had his prize in the mesh of the net. Grinning proudly, he hoisted the lunker for pictures. The fish measured a strong 21 inches and weighed nearly 3 pounds. The deep red spots that mottled the sides and the large undershot jaw pegged it a male.

We continued upstream, fishing the holes and bends. My first fish took a minnow from his hiding place under a bank. He was just a shade under 14 inches. Leapfrogging around John, I stalked in on a huge hole below a washed-out beaver dam. The spot looked like the domain of a lunker. Water flummed over the old dam, boiling into a hole. Rain drops pockmarked the surface as the river dug deep under the bank and then caromed around a bend to continue its way downstream.

Impaling a big lively minnow on the hook, I drifted the offering along the run and fed out line as it swirled deep into the hole. With no takers, I raised up on the rod, ready to lift the line free to cast again. In a flash a big fish boiled out of the water behind the minnow. He missed and zipped back into the depths, leaving me completely shaken.

Catching my breath, I nervously drifted the minnow down again. Once more nothing happened on the drift. Then the big brown swirled in behind the minnow, missing it as I began the retrieve. Experience had taught me to watch the antics of any fish that follows and I noticed that the trout hadn't tried to hit. He was curious but reserved.

The wind began picking up and the rain pelted into my face as I tried all the tricks of minnow fishing to fool the lunker. He was down to stay, however, and I couldn't get him to take another look.

Switching to a spinner John had given me, I cast 10 feet below the trout's hiding place and slowly wound the lure upstream. I stopped the retrieve every foot or so to drift the spinner back slightly, then worked in back upstream.

"Yahoo," I heard John yell, "look at this trout go." I glanced upstream through the rain in time to see John hotfooting it along the bank with a fish bowing the rod almost double.

I had just looked up to watch the battle when my rod was almost torn from my hands as a trout slammed into the lure. Taken completely by surprise, I reefed back on the rod so hard I jerked a big brown to the surface, saw him slash for the depths, and then felt the line go slack.

Expounding oaths befitting my actions, I reeled in the line and saw I had hit the fish so hard that the hook pulled free with a small bit of skin still attached. Feeling rather sheepish for losing the big brown, I moved up the creek to see John's fish. He was just creeling another nice brown of about 17 inches.

"Just missed one that was a whopper," I said, relating my tale of woe. "He must have been 22 or 23 inches. Sometimes I wonder if a guy ever does learn the fine points of fishing."

"Sorry you missed him," John said consolingly, "but you had better get to fishing. I'm one up on you and that first one is getting bigger all the time."

The next hour swirled by like the currents of the stream. John remained behind me as we worked upstream. I left him every (continued on page 33)

APRIL, 1963 5

RIGGED FOR RACING

WHAT MAKES A boat racer? They come in all sizes, shapes, ages, and occupations. They do have one common denominator, however. All are fanatics about their hobby. They are willing to leave straight from work, drive all night just in time to get their boat in the water, race, load up again, and take off for home a few minutes before they are due at the office again.

There is little in the way of prize money. Costs are high and the hot rodder never knows for sure how, or even if, his boat's motor will run. Jim Ludwig, one of Lincoln's top outboard racing bugs, had an experience last year that drives the point home. He left one evening for a race in Kansas City. The next morning before the race he decided to check out his new motor.

"I figured I had things all wrapped up," he explained. "With this rig hardly anyone in the race had

a chance to catch me. Just for the heck of it I tried

a test run. I must have gone all of 50 feet when the

motor jammed and there I was sitting out in the

lake with an engine with a hole in it big enough to

see the crankshaft.

lake with an engine with a hole in it big enough to

see the crankshaft.

"What could I do? I paddled back to shore, loaded the mess back on the trailer and pulled out for home."

The ardent racer was luckier a few weeks later. He borrowed an engine from a friend and went to another race. The motor blew up but at least he had started the race. To him, boat racing seems to have become a steady succession of "wait 'til next years". But he isn't complaining.

A grin spread across Jim's face as he told his tale of woe. If he didn't get a bang out of such things, he probably wouldn't be in racing. The ability to laugh off adversity and make a joke of disillusionment is probably, more than anything, what keeps him and other hardy souls in this risky but exciting game.

"Oh, it isn't unusual to quit in this business," relates Ludwig. "I suppose all of us do almost every fall. But during the winter months I start thinking how I might have won with a little bit better piece of equipment. The next thing you know it has been ordered and I'm hooked for another season."

In addition to Ludwig, Nebraska can boast such outstanding drivers as Jack Manning, Paul Leedom, Max Siegrist, John Quinn, Jerry Bishkup, Herman Gunn, Paul Hanson, and Priscilla Grosshans, all of Lincoln. Miss Grosshans is one of the few women drivers in the country. Racing experience ranges from relative newcomers like Manning who is starting his second season to Leedom and Miss Grosshans who have been active drivers since 1937.

Jerry Bishkup, who has been in racing since 1949, won the unlimited outboard (continued on page 31)

DROWN PROOFING

by Lou Ell New technique saves lives of many swimmers each yearTHE MAN watched his daughter's head sink into the water, her hair spreading like an odd water blossom on the surface. He knew she couldn't swim a stroke, but he did nothing. In a moment, her head reappeared. She unconcernedly took a breath of air, and sank again. The man glanced a few feet farther on. His son, barely a beginner at swimming, was floating limply, face down, his body rolling slightly like a strand of seaweed, with each undulation of the water.

But the children were not drowning; they were being udrown proofed". Both were learning to use the natural buoyancy of their bodies to stay afloat. With less than an hour of instruction, the two had found out all they needed to know to keep from drowning, should an accident dump them into deep water without life jackets.

Most drownings are due to fear—fear that tenses muscles and causes struggling. This leads to rapid muscular exhaustion. Air is driven from the lungs. The victim's head goes under. He gasps in water instead of air. If help is not available, he drowns.

Such a tragic ending happens every year in Nebraska.

The double tragedy is that it could be prevented if every person, young or old, who goes near

APRIL, 1963

9

the water would practice the simple drown-proofing

technique.

the water would practice the simple drown-proofing

technique.

This survival method, which the Peace Corps teaches its members and the Red Cross endorses, was developed by Fred Lanoue, head swimming coach at Georgia Institute of Technology. Its basic principle is ridiculously simple. The human body, with its fatty tissues and built-in air chambers, the lungs, approaches almost zero weight in water. With an average breath of air in the lungs, and the body completely relaxed, most people will float just under the surface.

There are individuals so buoyant they find it difficult to sink lower than chin deep. These people have slightly larger lung capacities, or may simply be fat, a condition that is of actual advantage in this particular circumstance. A fractional minority, it is claimed, cannot float at all, but the possibility that you or one of your family is of this type is extremely remote. Even those that cannot float can master the game if they learn to fill their lungs and hold their breath.

Knowing how to drown proof yourself before taking that unexpected tumble is all important. Check yourself out at the local pool, preferably under the guidance of a swimming instructor.

Once in water that you can barely stand up in, relax completely. Your body will feel almost feather light instantly. Your feet and legs will sink slowly until you are hanging vertically in the water. Aid yourself by letting your head fall forward into the water. Your back shoulders will come about to surface level, and you're floating, held up entirely by the water.

Maintain this position for a few seconds. Enjoy the completely disassociated feeling of being a part of the water. Then raise one leg slowly, and push the arms forward gently at the same time. Kick downward with the leg and thrust down with the arms, exhaling under water while you do so. The leg and arm thrust brings your head to the surface, where you raise your face above the water and get a new lungful of air. You immediately return to the relaxed position. If you were in trouble in deep water, you could continue on until help arrived.

Once you've accustomed yourself to this survival technique, try the jellyfish float. It offers an even more bouyant feeling. While floating in the survival position, double your knees and hug them with your arms, remaining perfectly relaxed. Keep your head down and you'll roll forward, your back to the surface. When you need a fresh breath of air, unlock your arms, kick your legs, and raise your face above the water. Inhale easily, don't gulp. Then relax into the knee position.

If you want to stretch out, the prone float is easy from the jellyfish position. Simply push your arms forward and your feet backward. You are still face down, but your body is parallel to the surface.

When you become tired of staring down into the water, raise your arms slowly, and clasp your hands behind your head. Roll over very lazily. Arch your back and chest a little, as if you were merely leaning back in a deep chair, and looking upward at the ceiling. Your face will likely just break out of the water, where you can exhale and inhale as you wish, without further trouble. Adjust your air intake to maintain yourself at the most comfortable floating point. The back float is probably the least easy to maintain yourself at a comfortable floating point.

Once you have mastered these techniques in the safety of a supervised pool, you'll be ready for anything. In any boating situation, of course, life jackets for each member of the party are required by Nebraska law.

However, people can fall off docks. They do step into deep holes while wading or fishing. Swimmers may find themselves tired out and still a distance from shore. In these, or any other situation that might plunge a person unexpectedly into deep water, floating techniques will keep you or your loved ones' from becoming statistics.

THE END 10 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

The GOURMET TREATMENT

Transform your catch into an inviting, mouth-watering delicacy by Kathryn CooleyWHAT CAN be done to the glistening beauties in your creel, once the catch has been given the gourmet treatment in the kitchen, makes any fishing trip worthwhile. After all, catching is only part of the game.

Because Nebraska has so many species, fish cookery offers the adventuresome chef a chance to come up with a variety of taste-tempting meals. Cooked right, even carp vies witn the more popular trout and catfish offerings. It's all in how you prepare the catch.

The following recipes and dressing methods are geared to coincide with NEBRASKAland's big springtime fishing spree. Once the creels are in, head for the kitchen. Our how-to guide is guaranteed to make your mouth water.

APRIL, 1963 11 the GOURMET TREATMENT

continued

the GOURMET TREATMENT

continued

Clean, wash, and dry fish. Season inside and out and brush with melted fat. Bake ot 350° F. for 40 to 60 minutes or until fish flakes easily v/hen tested with a fork. If needed to help the surface brown, brush with fat several times during baking. Serve on a hot platter.

the GOURMET

TREATMENT

continued

the GOURMET

TREATMENT

continued

Scrape off large scales. Cut fish to clean. Cut off head and split backbone for easy cooking

Season with salt and pepper and dip in a mixture of flour and corn meal. Place 'm heavy saucepan which contains Vs-inch melted fat. When the fish is brown on one side, turn and brown on other.

Season fish and place the trout on broiler pan. Brush with melted fat before broiling. Broil about 4 inches from the heat until brown. Turn, brush with melted fat, and broil until fish is brown and flakes easily when tested with a fork. Allow six to eight minutes for each side

Cleaning

Cleaning

Cook onion and celery in butter for a few minutes. Add bread crumbs, seasonings, and parsley.

FishWash and dry the carp and salt inside and out. Place the stuffing inside, skewer the opening together, and brush with melted fat. Top the fish with bacon and bake at 350° F. for 50 to 60 minutes or until the meat is flaky.

Heat deep fat at 375° F. Sprinkle fillet with salt and pepper, and dip in beaten egg, then in bread crumbs. Place layer of fish in frying basket and cook until done.

BIRDS of Spring

Presenting the Avian Artistry of C. G. "Bud" Pritchard The earth returns to life and is greeted by their merry warblingTheir cheerful warbling heralds the start of another year of life and growth. Regardless of the weather, spring has arrived when the many song birds return from their winter in the south. Life begins anew. Announcing their arrival with a song, they soon settle down to the business of raising another family. First comes the courtship, followed by the building of a nest. When the eggs hatch the anxious parents hover around, caring for their young.

The 24 water sketches presented on the following pages are representative of the many species that make NEBRASKAland their summer home. From the meadowlark, our state bird garbed in his bright lemon-yellow breast, to the lesser known species, these annual migrants brighten the life of everyone they come in contact with.

Painstakingly reproduced by Game Commission staff artist, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, these presentations are an excellent addition to the library of the novice as well as experienced song bird fancier.

Truly, life would be empty without the antics of these cheerful springtime visitors.

APRIL, 1963 19 BIRDS of Spring

continued

BIRDS of Spring

continued

BIRDS of Spring

continued

BIRDS of Spring

continued

A. Red-eyed vireo

B. Barn swallow

C. Brown thrush

D. Catbird

E. House wren

F. Yellow warbler

G. Bobolink

H. Yellow-throated warbler

I. Bluebird

J. Red-winged blackbird

K. Bullock's oriole

L. Baltimore oriole

A. Red-eyed vireo

B. Barn swallow

C. Brown thrush

D. Catbird

E. House wren

F. Yellow warbler

G. Bobolink

H. Yellow-throated warbler

I. Bluebird

J. Red-winged blackbird

K. Bullock's oriole

L. Baltimore oriole

Once Upon a CHALK MINE

Deep within a hill near Scotia lies a rich vein of state's historyIT WAS a school teacher's delight and a child's nightmare, a hill of chalk smack in the middle of the Sand Hills, and young Ed Wright figured he had it made. He wasn't planning on flooding the blackboard market with his new find. Instead he pictured building himself the prettiest gleaming-white building in the western frontier; a building made out of chalk.

This was a pretty far-fetched notion even for the 1890's. But Ed stuck to the idea, mining the hill from dawn to dusk, and eventually getting his building built. Folks from miles around came to Scotia to see his creation and do so today; it and the cave that was gouged back in the bowels of the hill once the chalk was mined in earnest. What Ed started could be one of our most unique tourist attractions.

Though undeveloped and unadvertised, Scotia's

chalk mine draws travelers off the beaten path to

explore its cooling confines. Paradoxicaly, the mine

and its past are more famous now than during its

years of operation. But this part of the rolling Sand

Hills has a rich history reaching back in the years.

Known as Happy Jack's Peak, this tallest of the surrounding hills was once used by pioneers on guard

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

against marauding Indians. It was named after Jack

Swearengen, a trapper who lived along the bluffs

overlooking the Loup River.

against marauding Indians. It was named after Jack

Swearengen, a trapper who lived along the bluffs

overlooking the Loup River.

Happy Jack's Peak really isn't chalk at all. The "chalk" consists of a seven-foot layer of an impure form of calcium carbonate at the base of the hill. The porous rock-like material is a part of the Ogallala formation that outcrops near Scotia. According to geologists, this same material is probably in other hills in the general area of Scotia. But only at Scotia has it ever been mined.

The mine, now abandoned, has a low, oblong entrance at the south side of the hill. There are several small openings nearby. It is appro "bed from the road by half-sliding down an embankment. Stooping to enter, the visitor is struck first by the stillness around him. In the winter months a covering of frost covers the ceiling for the first 50 feet inside. Light from the entrance is sufficient near the opening but further back a flashlight is needed

Off the main tunnel close to the entrance are a number of smaller room-like drifts, most of which are only three to five feet in height. Further back in the shaft the ceiling rises to a height of about 6V2 feet, allowing a person to stand upright. On either side of the main tunnel are a number of drifts 20 to 50 feet back before coming to an abrupt end.

The yellowish-white rock is almost glass smooth in some places and rough with small grains of darker-colored rock in others. The main tunnel originally ran through the hill to another entrance on the north but was closed several years ago.

A temperature of around 50 degrees is maintained in the mine, making (Continued on page 32)

SAND HILLS PRONGHORN

by Harvey Suetsuga District Game Supervisor Antelope reintroduced into this area offer great hunting bonusTHE PRONGHORN antelope have set down roots in the Sand Hills, and from all indications, it looks like they're there to stay a spell. Reintroduced into the vast 20,000-square-mile area during the largest antelope trapping and transplanting operation in 1958-61, the prairie speedsters are now increasing and spreading out into new areas of their historic range.

This is good news to anxious big-game hunters who have been watching the operation with keen interest, hoping that the increase will one day justify an open hunting season. Right now they're wondering when that first season will be held and whether the transplants are increasing at the expected rate.

Gathering this data takes time and patience both

of which are in, short supply. To sit back and wait

is tough at best. But to predict the outcome of the

introduction of a wildlife species into a changed

environment before all the facts are in is a risky

proposition. This is exactly the situation with regard

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

to the antelope releases in the Sand Hills. All the

facts are not in, and only time can supply all the

answers.

to the antelope releases in the Sand Hills. All the

facts are not in, and only time can supply all the

answers.

The reintroduction of the prairie ghost into the Sand Hills began in 1958, and over a four-year period, 1,077 antelope were released at 20 selected locations. Reproduction, herd movement, and dispersal over the range by the animals since their release have been studied closely. Late summer aerial reconnaissance of the release areas have been made each year to determine the rate of increase. Also, local landowner reports have been an important source of information for keeping the Game Commission posted on specific herd increases.

The basis for predicting the outcome of this project comes from information obtained from doe to kid ratios observed during these counts. By assuming that the rate of increase experienced thus far will remain about the same, one can predict what the future holds in store. By 1965, the population should increase to between 3,000 and 4,000 antelope. This is significant since the antelope population in western Nebraska has been estimated at 3,500 and 4,000 animals. With the Sand Hills herds, the state's pronghorn population will have doubled.

A 15 per cent mortality in all sex and age classes is assumed in making the estimate. Using these figures, the annual increase is near 26 per cent. The increase cannot go on unimpeded, but the point at which increase will level off is conjecture.

It would probably be well to go back to the beginning of the project and look at some of the reasons for antelope being brought into the Sand Hills. Past history indicates that the pronghorn ranged throughout Nebraska before the turn of the century. Travelers in 1834 reported them abundant near the mouth of the Platte River. Lt. G. K. Warren reported sighting many antelope in 1855 in the eastern portion of the Sand Hills.

With the white man's invasion of this prairie state and the changes that followed, the antelope disappeared from much of its former range. Keen vision and great speed were no match for the plow and rifle. Thoughtless slaughter and unwise conservation practices virtually wiped out the species.

Complete protection was instituted for the antelope in 1907. The natural increase was slow and it was not until 1953 that a limited hunting season was allowed. Since then, seasons have been held every year except 1958.

However, the antelope population was confined to the western panhandle region of the state. Because of the relatively stable land-use pattern in the Sand Hills and because Nebraska's grasslands were antelope range in the past, it was logical to believe pronghorns could be brought back to this area.

Another factor that led the Game Commission to initiate the project was the antelope's food habits, which are compatible with ranching. Pronghorns utilize woody plants and weed species, thus providing a balance with the cattle's grass preferences.

Over 400 stomach samples in Colorado, Montana, and Nebraska show conclusively that native grasses compose less than six per cent of the total diet. The studies reveal that the diet, on an annual basis, consists of 40 per cent woody plants, 43 per cent weeds, and 10 per cent cactus.

The studies indicate that grasses are consumed mostly in the spring of the year. Even at that time the other woody plants and weeds make up the bulk of the antelope's intake. During the summer, weeds constitute up to 60 per cent of the dietary needs. Woody plants are preferred during the winter, when they comprise up to 70 per cent of the diet. In unusual cases, where green forage is especially attractive, some damage may be encountered.

One of the most encouraging aspects of the project has been the interest shown by the ranchers themselves. Voluntary sign-ups for the release sites, totaling over one-half million acres or roughly 13 per cent of the Sand Hills area, clearly indicates the rancher's interest.

Has the massive transplanting project been successful? Other states which have carried on such a program have generally classed the project as a success if an open season could be held within 10 years following releases. Much depends on the survival of young. If the present rate of increase continues, we should be able to hunt antelope in the Sand Hills during the latter half of this decade. That is the news sportsmen have been waiting for.

THE END 27

Robin Hood RABBITS

by Marvin Tye For us bow hunters, it's sport first, then meat for the tableRON MEYERS and I had shot at enough cottontails to have filled out an hour ago. Running shots and jump shots, long shots and close shots, you name it and we'd taken it. But not with rifles. Ron and I were bow hunters in search of sport first and meat for the table only if we were lucky enough to score.

Maybe the cottontails realized we had penalized ourselves. None of the many that we had shot at seemed too worried that they would end up in the frying pan. The two of us had worked two prime spots without success and were now in search "of another. Ron drove slowly along the little-used gravel road near Lincoln. Nearing a bridge, he slammed on the brakes and grabbed for his 58-pound-pull hunting bow.

"That spot is loaded with bunnies," Ron said as he packed four razor-sharp broadheads into his bow quiver. "You walk down one bank and I'll take the other. One of us should connect before we leave."

Ron slipped another quiver holding a dozen arrows over his shoulder. At least he would not run out. I had brought only seven arrows, but had lost one in an earlier shootdown. I strapped the belt quiver around my waist and we quietly slipped into the ravine.

Meyers spotted game first and began to shoot.

His first shaft flashed down and I could see a

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

startled bunny running along the bank in my direction, wondering where the silent arrow had come

from. Two more cottontails flushed and Ron gave

his attention to these. My first arrow hit close

enough to make my target move behind screening

brush. The next shot sliced through the cover and

the bunny was again in the open. At the third shot

he began to run. I led him too much on the fourth.

He stopped on the bank about eight feet below Ron.

Meyers' shaft caught him dead center and he never

knew what hit him. Another bunny flushed at the

shot, and my last arrow passed within an inch of

his bouncing tail. Between us, we had fired at least

two-dozen shots to bring down one rabbit.

startled bunny running along the bank in my direction, wondering where the silent arrow had come

from. Two more cottontails flushed and Ron gave

his attention to these. My first arrow hit close

enough to make my target move behind screening

brush. The next shot sliced through the cover and

the bunny was again in the open. At the third shot

he began to run. I led him too much on the fourth.

He stopped on the bank about eight feet below Ron.

Meyers' shaft caught him dead center and he never

knew what hit him. Another bunny flushed at the

shot, and my last arrow passed within an inch of

his bouncing tail. Between us, we had fired at least

two-dozen shots to bring down one rabbit.

That's the way it is when you bow hunt for bunnies, lots of action but little game. It's one of the best ways possible to practice for deer hunting. All shots are taken at unknown distances at targets that move away before you have a chance to get the range. The bow hunter who uses his big-game tackle for this sport is more than ready to take on deer.

The key to success in bagging cottontails with a bow is being able to spot the prey. According to Meyers, the trick is to look for anything that does not seem natural. He examines each stump or mound of dirt. Many turn out to be rabbits.

The nearest to a bow-hunting purist that I have met, Meyers uses a gun only to hunt pheasants and ducks. His arrows have brought down pheasants on the wing. Other victims include fox, coyote, squirrel, and deer. Meyers does not believe that it is necessary to travel 100 miles to find good hunting. He has taken deer within three miles of downtown Lincoln.

Meyers has been hunting with a bow since he was seven. With Nebraska's variety of targets, Meyers has been able to hunt throughout the year. With all of this practice, he has developed a fantastic ability to spot game. An animal not much larger than your shoe is difficult for the average person to see in thick brush. A light snow makes the job a bit easier, but not much. Meyers' eyes seemed to be drawn like a magnet to the slightest motion. On our outing he spotted a bunny where I could see only brush.

"How could you tell the cottontail was there," I asked.

"I saw his ears move."

"Did you see the rabbit?"

"No, just the ears."

That bunny was about 50 feet away and off to one side.

We found most of our game in patches of brush along creek banks. The heavy growth offered the rabbits both shelter and food. Rabbits are plentiful in Nebraska. In our short two-hour hunt, we must have seen at least 30. Rabbits (continued on page 31)

APRIL, 1963 29

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

Hooked MallardPENNSYLVANIA . . . District Game Protector Jay D. Swigart received a call concerning a wild mallard duck. It seemed the duck had swallowed a fish hook. Out of the mallard's mouth hung a foot of gut leader and yellow bobber, hindering the duck's eating and flying. Assisted by another man, Swigart removed the mess of fish gear. The duck, without even a thank you, took off for parts unknown.

Water BreakCALIFORNIA ... An incident near Barstow during the opening week of the dove season points up an outstanding example of sportsmanship. Two reserve wardens noticed a continuous barrage from dove hunters for a day and a half near a well. They also observed a large concentration of quail and chukar partridge. On the second day the two wardens acted. They approached the hunters and asked them to move away from the well so the birds could get a drink of water.

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cents a word: minimum order S2.50 DOGS TRAINING—Retriever and bird dogs. Gun-dog or field trial dogs worked on pigeons, ducks, quail, and pheasants. Individual concrete runs, best of feed and care. Dogs boarded year around and conditioned for hunting. English setter and Labrador stud service. Platte Valley Kennels, Rt. #1, Box 61. Ph. Du 2-9126, Grand Island, Nebr. VISZLA PUPS. Right age for starting next season. Champion bloodlines; Selle, Ocla, & Kubis. AKC & FDSB Registered. Tails clipped, shots. R. C. Reinhardt, 104 E. 21st, Scottsbluff, Nebraska. (RATTAIL) IRISH WATER SPANIEL puppies for sale. AKC Registered. From hard hunting parents. Championship lines, photos, pedigree furnished. Paul Sullivan, Sidney, Nebraska. GUNS NEW USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS— Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca, Colt, Ruger and many others in stock. Buy, sell, and trade. Write us or stop in. Also live bait. Bedlan's Sporting Goods. Just off U. S. 136, Fairbury, Nebraska. COMPLETE LINE of all makes of newly made M.L. guns and accessories—Best prices going—M.L. Gunsmithing—Rifles custom built —Write Dr. Carlson, Crofton, Nebraska. MISCELLANEOUS GET IT TODAY! The Hungry Sportsman's Fish & Game Cookbook. Over 400 recipes. Includes mushrooms frogs, etc. $1.00 post-paid. Eddie Meier, Box 3030, Scottsdale, Arizona. SNAGGER FISHERMEN—Get down to the bottom. Get the big ones. Try the new Skitter Snagger Rig (2-7/OHks-2-2ozWts) $1.10 ppd. Skitter'Products, 205 So. 15th, Norfolk, Nebr. Skitter Weights are made in ten sizes, V2 oz. to 34 lb. to fit all treble hooks 1/0 thru 14/0. Dealer Inquiries Invited. FARM VACATIONS. Family Rates. May-November. For information, write Mrs. Gerald Snyder, Steel Creek Stock Farm, O'Neill, Nebraska.SNYDER

Perfect for Fishing / Hunting / Vacations / A Trip to the Mountains Save on costly motel, hotel bills with the strong, lightweight easy-to-keep-clean fiberglass carry-all/sleeper.Two men can easily lift and install it in just minutes. Sleeps at least two and fits on most standard pickup trucks. Side awning windows,frontand rear picture windows with chrome hardware throughout. Complete ventilation and self-insulation makes the SNYDER Sleeper comfortable in any kind of weather. When not in use, store off-season lawn equipment, or let the kids play in it. AT ABOUT HALF THE COST OF SOME COMPETITIVE UNITS $ Designed and Manufactured by 195° COMPLETE f.o.b. Lincoln (terms available) WIDE box long wheel base (style sides) WRITE FOR INFORMATION AND/OR IMMEDIATE DELIVERY OR CALL 434-1519 "BUILDERS OF THE BEST" FIBER GLASS COMPANY 3701 North 48th Lincoln, Nebraska

RIGGED FOR RACING

(continued from page 7)hydroplane title at the national championship in 1955 at Mt. Carmel, Illinois. The following year he set a new world record in the Class F hydroplane class.

"I didn't even know about the record until after it was all over," said Jerry. "I was running about two-thirds throttle all the way. It would have been fun to open it all the way to see just what would happen."

The engine used in a modified outboard racer is as different from the runabout engine used for fishing as the family automobile is from an Indianapolis Speedway racer. They start out as conventional engines, but by the time they have been modified they are capable of about twice the horsepower and hit speeds close to 70 miles an hour.

As expected, the cost of having engines modified runs into a fair piece of change. By the time the flywheel is balanced and myriad other jobs completed, the bill can run from $175 to $375.

In addition to special engines, racing fuel is used which consists either of the conventional gasoline-oil mixture or a combination of a quart of castor oil to 4% gallons of methylated alcohol. Modified rules permit the use of any fuel, just so long as it is a liquid. This keeps the drivers in constant search for new concoctions.

A racing outboard isn't exactly what you would have in mind for a family outing. It is about all one person can do to squat in the compact craft. Racers range in size from eight feet for the small Class A models to 12 feet in Class D. The boats come in two models, runabouts and hydroplanes. Runabouts have conventional hulls while hydroplanes ride on sponsons. Needless to say, they're built for speed, not comfort.

A racing rig can dump a driver into the water at a moment's notice. Herman Gunn, who weighs about 235 pounds, was competing in the nationals three years ago when his boat flipped. The big man skipped across the water three times and then went under. He started flailing with his arms and legs to keep from drowning only to discover he was on a sand bar in water only two feet deep. Then he waded to shore.

Those who laughed at Herman's near-drowning were laughing at themselves as well. This isn't a sport where you can take yourself seriously. If you do the next boo-boo may be your own. It doesn't do any good to cry when a $1,000 rig goes to the bottom of the drink.

In spite of the heartbreaks associated with racing, there are plenty of compensations. Recognition from other drivers after winning goes a long way toward making it an enjoyable sport. Racing teams quite often are made up of families, with dad driving while mom and the kids act as his pit crew. Traveling around the Midwest gives drivers an opportunity to meet competitors from other states and make lifelong friendships.

Newcomers to racing usually get a rude awakening to the sport. They generally start with a used rig and learn to their sorrow that they can't keep up.

"It isn't too bad when you can stay close," says Max Siegrist, a two-year enthusiast. "But when they start lapping you it's time to either get out or buy a better rig. The day comes when you win a race and you're on Cloud Nine. But things have a way of evening themselves out and first places get scattered around enough for everyone to have a fair shake."

The advent of spring is bringing the boat racers out of hibernation. Soon they will be back in business, beating their hearts out trying for another mile an hour out of their rigs, on top of the world when they win and always ready to laugh if Lady Luck doesn't look their way.

THE ENDROBIN HOOD RABBITS

(continued from page 29)are not really spooked by an arrow, and often move only a short distance. This gives the archer a chance for several scoring shots.

The shots that are missed are remembered perhaps more vividly than those that connect. If you miss with a gun, who can tell how close you came. An arrow flashing over a bunny's ears or kicking up snow under his chin gives a much better picture. An added thrill is provided when arrow and rabbit meet with a solid "chunk" that means the game is yours.

Running shots with the bow are extremely difficult. Almost any archer will miss more than he will hit. Meyers and I nearly always fire at a running bunny if there is any chance of getting it. A hit almost anywhere will down a cottontail.

In shooting at a running rabbit, the archer sometimes has to figure how high off the ground to aim in addition to how much lead the animal should be given. Rabbits often leap through the snow, bouncing like a rubber ball.

I was thinking about this as I walked on down the ravine. Spotting a thick patch of brush I eased over, hoping to kick out game. A cottontail exploded right at my feet. He seemed to be jumping about 12 inches off the ground. In a split second, I decided to lead him about three feet and hold a foot high. The arrow flashed so close to his head that I thought for a moment he was mine.

But near misses don't count. Meyers had connected with two more, his bag of three looking hard to beat. We worked the ravine until we were convinced that the cottontails had finally learned what our sleek arrows could do to their clan. It was getting late and Ron and I were anxious to cook up a mess of fried cottontail. It had been a fine afternoon, a great way to enjoy Nebraska's bountiful game resources.

THE END APRIL, 1963 31

ONCE UPON A CHALK MINE

(continued from page 25)it pleasantly cool in the summer months. In the winter the colder outside air causes a fog-like mist to hang close to the ceiling.

Even in its heyday the mine was never a big enterprise. When first opened in the early 1890's, dynamite was used to blast the rock which was then hauled away by teams of horses. Use of explosives caused a cave-in in 1907, killing Edmund Van Horn. After a short interval Van Horn's son, Ernest, took over the mining operations. He tried making bricks from the chalk but was unsuccessful and the operation was discontinued.

Mining was resumed again shortly after 1930. An Omaha paint manufacturer reopened the mine, using the chalk for paint, whitewash, and other products. But that, too, was given up when it was found pure chalk could be shipped cheaper from England. Today the mine is again abandoned, used only by families on picnics, by curious children on exploring adventures, and tourists who know of its existence.

Does it have any tourist appeal? Meredith Williams, editor of the Scotia Register, thinks so. "There's one small sign on the highway advertising the mine, yet many people stop by here every summer asking directions to it. As far as I know, it's the only mine, running or not, in the state. It is an interesting experience for anyone to visit it."

Williams has a personal interest in the mine. During his undergraduate days at the University of Nebraska he worked one summer with the Highway Department in Scotia during construction of the present road that runs alongside the hill.

"The contractor didn't know of the chalk when he bid on the job. He assumed Happy Jack was just another of the Sand Hills. The chalk couldn't be dug out economically and blasting didn't work too well, either. I understand he went broke on the job and later ended up on the WPA."

As the only mine in NEBRASKAland, the Scotia chalk hill has a place in today's world. Formed over a million years ago, it could be developed into a stop-over anyone would be sure to include in his vacation trip. It could, with some effort and capital, be a hundred times more profitable than it ever was in the past.

THE ENDBOAT TRAILERS

Now there's a low loading Golden Rod Boat Trailer for easiest launching and loading... safest trailing. And there are Golden Rod trailers for every size of boat —all with the features you want for easier handling, easier pulling. See S-.' them at your marine dealer. Nebraska made for Nebraska needs DUTTON-LAINSON COMPANY Est. 1896 Hastings, NebraskaEVERY SPORTSMAN WANTS TO KNOW

When fish will feed, when birds will fly and when all wildlife will be active. WE CAN TELL YOU! Our SOLUNAR TABLES for 1963 forecast these times TO THE MINUTE, a full year in advance. Based on a natural law discovered by southern market hunters years ago, the SOLUNAR TABLES will allow you to plan your days afield so that you can derive the BEST from your precious free time. YOU CANT FOOL PEOPLE FOR 29 YEARS! Now in their 29th year of publication, the SOLUNAR TABLES are translated in seven foreign languages throughout 1 1 foreign editions. Syndicated on the sports pages of 141 newspapers, the SOLUNAR TABLES forecast accurately the day-by-day feeding times of game and fish where YOU happen to be. Sportsmen the world over depend on the SOLUNAR TABLES. Why don't you? OUR SPECIAL OFFER TO NEBRASKA SPORTSMEN The perfect gift to any outdoorsman, the SOLUNAR TABLES for 1963 can serve you as a present unrivaled in economy and thoughtfulness. On all orders of six copies or more, we will offer you a big 20% discount. Offer expires June 15th, 1963 ... no stamps or C. O. D's please. DEALER INQUIRIES INVITED John Alden Knight P. O. Box 208 Williamsport, Pa. Please rush me PRICE — $1.00 per copy postpaid copies of the 1963 SOLUNAR TABLES. I enclose Name Address Town or City State PLEASE print or type your order

TROUT IN THE RAIN

(continued from page 5)other bend to fish. As it worked out, mine were the wrong bends and his the right ones. Three good browns eventually slipped into my creel, the largest a sleek 16-incher. I raised two large trout, but try as I may I couldn't get them to take.

John's luck on the lunkers had run out for the day, and he ended up creeling four more fish in the same class as mine. The rain was beginning to come down in sheets now, with a strong westerly wind whipping across the meadows. John motioned for me to hike back to the car where we met again to compare catches.

"I like your idea of fishing in the rain," John chuckled. "Nicest bunch of trout I've taken this spring."

Nor could I complain, even though I had missed the old bull brownie. As we pulled out of the meadow and headed back for the highway, water began showing in small pondlets in the low ground. The prairie seemed to be springing to life as the rains cleansed the dust from its face. The storm had prodded the browns into a feeding spree, the pock-marked beauties less leary when the rain began pelleting the surface of their domain. With extra feed washing down the stream to tempt the brownies, we had hit the Niobrara at just the right time, a time every angler dreams about.

THE END

notes on Nebraska fauna...

FRANKLIN'S GULL

OF THE various descriptive names which have been given the Franklin's gull, one which has been overlooked is "Excitable Extrovert". This is one bird which loves crowds during all daily, seasonal, and annual activities.

A bird of the open plains, the Franklin's gull reaches the sea only during the southern migrations. He roosts in large numbers on large water bodies at night, flies several miles at dawn to feed on land insects over fields, and returns to water at dusk.

One of six dark-headed gulls, the bird is recognized by his black head, dark slate back, pale rosy

breast, white-tipped primaries, dark red legs, and

red bill. Various shades of white and gray complete

the body coloration. The Franklin's may be confused

with Bonaparte's gull except that the latter is a bit

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

smaller with lighter back, primaries tipped with

black, black bill, and orange-vermillion legs.

smaller with lighter back, primaries tipped with

black, black bill, and orange-vermillion legs.

The breeding range extends from northern Iowa, southern Minnesota, and South Dakota into the southern Canadian provinces. Since this area borders northern Nebraska, some colonies may nest in the northern Sand Hills. No records have been published to verify this, however.

This gull is one of the few birds which summers in interior North America and winters in the southern hemisphere. Those Franklin's which winter along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas migrate much shorter distances than those which travel down to central Chile, Patagonia, and Peru. Rare observations have been made of the bird wintering in California and Colorado. As with some other water birds, an eastward migration occurs to Lake Ontario, Massachusetts, and New Brunswick, but the number of birds recorded is insignificant.

Nebraska ornithologists conducting spring bird inventories in May have observed the Franklin's gull in 35 counties. The bird probably occurs in other areas not censused during migrations. Since this species arrives in Minnesota in April, he probably gets here prior to or about the same time. Look for him after the sloughs, ponds, and lakes are clear of ice, since the bird requires water for resting and roosting sites.

Once the gull moves through to summer range he is not seen again until fall when large groups congregate on larger water bodies. When migrating, undulating lines or V's with long stringers of birds are the rule.

In searching for nests, look for large colonies, sometimes in groups of several hundred birds. Nests are built of reed or rush stems on a floating foundation of these plants in water up to six feet deep. Large sloughs or grass-grown lakes are a good bet when nest hunting. Unlike other birds, the Franklin's usually changes nesting sites each year. The colony may rest on the same lake as in previous years but along different shores, or the whole colony may move to an entirely new lake.

Eggs are laid in clutches of two to four but there are usually three in a nest. They vary in shape, color, and markings. Generally pear-shaped, the eggs' colors range from light gray-blue through olive brown to chocolate brown. Irregular blotches of diverse designs and dark colors appear on the surface. Although literally endless egg descriptions exist for this species, those of any one set are similar enough to each other that they can be matched after having been mixed in with many other eggs.

The chicks are pale-billed, pink-footed balls of down. Shortly after hatching the majority of young take to the water. At this young age, they can be capsized by a gentle breeze or if they bump into a rush stem. The little fellows quickly upright themselves, however, and appear dry and fluffy. When chicks are caught in rough water a considerable distance from the nest, adult birds flying above try to herd them back to safety. If this fails, several adults take turns lifting the chick by the nape of the neck and hurling him in the direction of the nest. This procedure is repeated until the chick is safe.

Young are readily adopted by any nesting adult, and it is not uncommon to see a parent with 10 or more chicks in custody. Food of the young consists primarily of dragon-fly naiads, which are usually abundant at chick-hatching time.

Food varies with the seasons for adults. During early spring and late fall considerable quantities of aquatic life are eaten. With the commencement of spring plowing, hundreds of gulls follow the plow, consuming cutworms, grubs, and earthworms exposed in the furrows. This hovering-following-feeding habit has resulted in the names of "prairie pigeon" and "prairie dove". During the nesting season insects, especially grasshoppers, locusts, flies, and gnats are taken almost exclusively. Because of his insectivorus habits, the gull is of great economic value.

The Franklin's has several midday flight patterns which can be attributed only to playing or restlessness. One of these involves a leisure upward spiral until the bird is almost invisible from the ground. During the ascent, a musical "po-le-e-e, po-le-e-e" is uttered. At the upper end of the spiral, the wings are partially closed and the gull plummets toward the lake, checking its dive only a short distance above the water surface. He may wander about for a brief period and then repeat this ascent and dive performance.

Beneficial to agriculture and possessing graceful beauty, the Franklin's gull is a valuable asset of the Nebraska fauna community.

THE END APRIL, 1963 35

DOUGH BALL How To

Designed to tempt the appetite of the most discriminating, is this baitMOST OLD-TIMERS swear that nothing tempts the appetite of a hungry carp like the time-honored doughball. The concoctions dreamed up over the years have been weird and wonderful, and here's one that is called a real killer by those who have used it.

Mix 1 cup white flour, 1 cup yellow corn meal, Vz cup oatmeal, V* cup grated Parmesan cheese, and 1 tsp. sugar together while dry, then add enough cold water to form a stiff dough. Knead until well mixed, then pinch off pieces and form into balls about the size of a small grape.

While you're doing all this, be boiling a quartered onion in a saucepan of water. Remove the onion pieces when done, and discard them. Pour the doughballs into the boiling water, and cook until they rise to the surface. This takes only a minute or so. Remove the balls with a spoon, and lay them out to cool and harden.

These tough pellets will keep for days, and may be freshened somewhat before using by placing a damp rag over them, or storing in a tight container and kept cool. THE END