OUTDOOR Nebraska

MARCH 1963 25 cents CRAZY FOR COTTONTAILS PERCH ON THE ROCKS Sand Hills Lake Sets 'Em Up OGALLALA Cowboy Capitol of the West PLUS: Road Killer, Nebraska Bullets, and New Red Willow Reservoir

OUTDOOR Nebraska

March 1963 Vol. 41, No. 3 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. GREG SMITH, managing editor; Bob Morris, Marvin Tye, C G. "Bud" Pritchard

...NEBRASKAland's newest playground RED WILLOW

IT ISN'T quite true that it will be necessary to arm yourself with a ball bat to be protected from the fish at Red Willow Reservoir, Nebraska's newest reservoir. But the exceptional growth rate of each species planted there in the past year has been such to make both fishery technicians and anglers blink their eyes in wonder.

Fantastic, fabulous—these are just two adjectives

being used to describe the fishing potential of the

newly-opened Republican watershed impoundment,

seven miles north and one west of McCook. Some of

the over one-million fish planted there since 1961

increased in size five times in just one year. Others

MARCH, 1963

3

in one short summer were six times larger than

when stocked.

in one short summer were six times larger than

when stocked.

But the impressive fishing potential of this newest of southwest Nebraska's big reservoirs is only one of the many great recreation opportunities that will soon be available. In for equal plaudits are a 35-mile shore line ready for exploring by boaters, a variety of game species on 4,289 access-assured acres, and an array of sites for camping or building cabins. It all adds up to a big recreation windfall.

The old adage that an acre of water is worth a thousand acres of land has meaning here. Where once a small and muddy stream pushed its way to a date with the Republican, a 1,600-acre water playland has blossomed.

The Game Commission has worked with the Bureau of Reclamation in acquiring recreation land around the power and flood-control impoundment. Cost to Nebraska sportsmen has been but a fraction of that which would be incurred if the state had to start from scratch and build a lake such as this.

Red Willow's worth plenty for the recreation that it will offer. But it will be returning plenty, too. Studies show that its sister impoundments—Enders, Swanson, and Medicine Creek—bring in a whopping $1.4 million annually to the area. This comes close to having your cake and eating it, too, a classic example of the dollars-and-cents value of outdoor recreation.

Construction began at Red Willow in the spring of 1960 with closure coming in the fall of 1961. The big impoundment is fast taking shape, although it is not yet filled. It is the last of the reservoirs planned for the Republican watershed and was completed at a cost of approximately $7 million.

The background on Red Willow and the reasons

for the unusually fast fish growth rate go back to

the renovation of the entire watershed prior to stocking.

Considerable time and work went into surveying the area in order that all bodies of water could

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

be treated. Permission to rotenone was obtained from

every landowner with a pond, slew, ditch, or creek

that empties into Red Willow.

be treated. Permission to rotenone was obtained from

every landowner with a pond, slew, ditch, or creek

that empties into Red Willow.

In early September 1961, the rotenone was applied from 18 stations on the 51 % miles of the stream. The one-day operation was highly successful in ridding the watershed of rough fish. Technicians found at that time that rough fish comprised about 75 per cent of the stream's fish population by weight.

Red Willow has always had a large concentration of rough fish. It was one of the muddiest streams in the state. Within a few days after the rotenone was applied, however, the water cleared up and remains that way today.

The successful growth rate of the fish now in the watershed can be traced to the fertility of the new reservoir and. to the effective eradication of the rough fish. Red Willow was ready for planting game fish about a month after treatment. The first release consisted of about 647,000 fingerling channel catfish, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, bluegill, and crappie. Minnows and crawdads for forage were also stocked at this time. In June, 1962, 104,000 two-to three-inch northern pike and 285,000 walleye were released.

Fishery technicians sampled the lake on July 20, 1962, and found the smallmouth averaged 6V2 inches and the largemouth, 7% inches. A month later, samples showed the smallmouth averaged eight inches with the largemouth bass measuring nine inches. Bluegill which had been about two inches long when stocked had increased to an average of six inches each.

Another sampling in October 1962, surprised the technicians even more. This time thev found the bass had stretched out an additional two inches. Northerns averaged a whopping 15.3 inches with five reaching 22 inches and weighing three pounds. Only one walleye was taken but it went 15 V2 inches and weighed nearly a pound. It all adds up to some great fishing in the future.

At no time in their sampling have fishery technicians found any rough fish. There may be some somewhere in the lake or watershed, however, but the northern pike and walleye can keep a small population in check.

But fishing isn't the only feature at Red Willow. Two day-use areas, one on each side of the dam, have already been completed, with each having a boat ramp and picnic facilities. Another similar area is designated for development across the lake from the dam. A 50-acre overnight camping area is ready and 77 cabin sites with water-front access are planned.

When habitat plantings are fully developed, adjoining lands will provide excellent hunting. Deer and pheasant are already found in good numbers. Waterfowl are using Red Willow's waters as a stop-over and resting spot. Some 23 Rio Grande turkeys were introduced in the winter of 1961-62 and have since multiplied and could be a hunting bonus in future years. Prairie dog towns are located nearby, giving the area an almost complete game population.

As the final link in the Republican River chain of reservoirs, Red Willow makes southwest Nebraska a true recreational haven. The nine-county area now boasts four big impoundments, providing top recreation for 46,000 people in the area and a host of other Nebraskans and out-of-state fun seekers.

In a little more than a year Red Willow has changed from a muddy stream with little to offer to an attractive lake boasting fishing, hunting, boating, camping, and other great recreation opportunities. It's sure to be one of the outdoor hot-spots of NEBRASKAland.

THE END MARCH, 1963 5

PERCH ON THE ROCKS

by Bob MorrisIT WAS COLD, biting cold there in the middle of Cameron Lake. I stood poised over the five-inch hole in the ice, twitching the stubby jigging rod in hopes of attracting a perch from his frigid lair. To catch fish through the ice, you have to jig the bait up and down. I figured I ought to be catching plenty. My shivering kept the rod in constant motion.

Gene Hornbeck, Jack Johnson, and I had been fishing for almost half an hour in the clear January air, but so far had been blanked. Fat Herefords grazed nearby, the steam surrounding their faces appearing as if they were smoking instead of munching on the hay spread out on the snow before them. Behind the cattle the Sand Hills stretched on toward Bassett, 25 miles away.

Numbed as I was, I began to wonder whether I

would feel a strike if it came. A sharp tug on the

two-pound monafilament line let me know I had no

reason to worry. Forgetting for the moment that

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

this wasn't conventional fishing, I played my catch,

yelling all the time at Gene.

PERCH

ON

THE

ROCKS

continued

this wasn't conventional fishing, I played my catch,

yelling all the time at Gene.

PERCH

ON

THE

ROCKS

continued

"I got one, I got one," I yelled.

"What's the matter, too big for you to pull in by yourself?" Gene hollered back.

I flipped the perch out of the hole. He flexed his sides, seemingly fighting the January cold as much as the hook. The perch struggled free and fell to the ice, flopped three or four times, then lay still, frozen stiff.

Everything seemed warmer then. My hands were no longer cold, even the numbness went from my feet. We had come a long way for these perch and already were on our way to an action-packed day. Another perch took my lure moments later and was quickly laid out next to the first.

Gene skidded over, gave the frozen duo a glance, then removed the eye from one, claiming it to be the best bait of all. Back at his trio of holes, he fastened the bait to a hook and dropped it in. It wasn't more than a few minutes before he had a taker pulling at the line.

"I thought you said the perch here weighed more than a pound," he shouted over to Jack, reeling in his eight-inch catch. But he wasn't complaining.

When we arrived at the lake after driving through the rolling ranch country, our Bassett fishing partner pointed out his favorite spot. "There's a flowing well about a hundred yards out. If we fish near it we should do well today."

The temperature was fighting to get up to zero. Loading our gear on Jack's sled we started trudging out toward the spot. Once on location, Gene put his ice auger to work and in short order had 10 holes drilled through the 18-inch ice. In another 15 minutes our lines were rigged and we were ready for action. Both of us manned a jigging rod, all the time keeping close check on our bobber-rigged fish sticks spotted in the other holes. Each of us could legally put out 15 hooks. Jack had set up three lines and was checking out other spots around the lake, spudding holes at random.

About the time Gene had caught his first perch, Jack was back tending his lines. We would use the small rods for a while, then make our rounds of the bobber-rigged lines, clearing the holes of newly-formed ice and bringing in the fish.

Our arms didn't get sore from pulling perch out, but the fish came often enough to keep our spirits up and the cold from going through our bones. Just to show the perch played no favorites, Gene used eyes exclusively, Jack stuck to minnows, and I continued with the jig with a yellow streamer. We came out about even, with no one getting the upper hand with his favorite bait.

Jack had to get back to town, leaving Gene and me alone on the lake. The defused rays of the sun started losing their warmth. By mid-afternoon the temperature started dropping. The holes were icing up faster now but the constant job of keeping them clear kept us warm. We still hadn't caught any perch in the pound-plus class but the six to nine-inch ones would make a good meal.

"As far as I'm concerned, you can't find a better eating fish than this," Gene said, hauling in another pan-sized beauty. "They really hit the spot in the winter."

The thoughts of the upcoming dinner made my mouth water. I could almost see them served on a steaming plate. The winter months do something to the taste of all fish. The flesh is firmer and the taste improved.

In addition to Cameron there are a number of lakes stretched from one end of the state to the other that are ideal for perch. Crappie, bluegill, northern pike, and walleye are added bonuses.

Finally calling it a day, we gathered up our gear, threw the fish into a burlap bag, and started back to the shore. The car labored through the frozen ruts of a road. Rounding a small hill with scattered hay stacks to the left we both looked almost unbelieving at the sight before us. Clustered near one stack were a band of antelope, possibly some of those introduced in the Sand Hills a few years ago. They watched us closely but stayed put.

"Turn over that way and make a big circle toward them," Gene said, grabbing for his camera at the same time. We got within 30 yards or so and I stopped the car as Gene snapped the shutter. As we circled closer the antelope started moving off in a slow trot. Gene shot another picture and then the antelope took off in high gear.

We stopped twice more on our way back to the road, getting out each time to open a gate, drive through, and then stop again to close it behind us. There is nothing worse than leaving a gate open with cattle around.

Back on the main road Gene headed the car north toward Bassett and dinner. Splitting a candy bar we discussed the lack of ice fishing popularity.

"I can't understand it," said Gene. "You can catch just as many fish in the winter as summer, they taste a heck of a lot better then, and the bugs never bother you."

"Yes," I replied, "and neither do too many fishermen. Let's face it, the hard-water angler has it made."

THE END 8 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

OGALLALA Cowboy Capitol of the West

by J. Greg Smith Wide open and no holds barred, it took on the best of the Chisholm Trail rawhidesAS FAR AS old-time Nebraska rawhides are concerned, Dodge City is just a spot on the m m trail. Give them Ogallala anytime, the place where the cowboys are the shootingest, the sheriffs the bravest, and the dance hall gals the prettiest.

All this was a couple of yesterdays ago, a time when there wasn't a trace of barbed wire in sight and a man's spread nudged the horizons. This is as it was at the forks of the Platte in 1875, the makings of NEBRASKAland's Wild West legend.

Sure, Dodge had its Matt Dillon. But Ogallala

claims Martin DePriest, a man who could make his

MARCH, 1963

9

pair of Colts bark a language that the orneriest of

Texas drovers could understand. Backing him up

was Joe Hughes. Though without the classical gimp

as seen on TV, he sported a buffalo gun that convinced many a redeyed wrangler to rodeo somewhere else.

There were the Kitty's, too, but never

enough to go around. Big Alice reigned here, and

though she was a little worse for wear, she and her

counterparts looked mighty good to the rawhide

whose only company had been a half-wild string of

longhorns on the Chisholm Trail.

pair of Colts bark a language that the orneriest of

Texas drovers could understand. Backing him up

was Joe Hughes. Though without the classical gimp

as seen on TV, he sported a buffalo gun that convinced many a redeyed wrangler to rodeo somewhere else.

There were the Kitty's, too, but never

enough to go around. Big Alice reigned here, and

though she was a little worse for wear, she and her

counterparts looked mighty good to the rawhide

whose only company had been a half-wild string of

longhorns on the Chisholm Trail.

Such were the people of Ogallala during the heyday of the trail. Though boasting only a scant hundred residents at best — not counting a couple of dozen hands who had taken up permanent lodgings on Boot Hill—Ogallala was known far and wide as the hell-raisingest, rip-roaringest cow town west of the Missouri.

Ogallala stuck its roots down when the Union Pacific pushed west. But for the next 10 years, it looked like a strong wind would blow it away. Then the longhorns began to move in, a couple of thousand head at first, then herd upon herd, as stockmen discovered what Nebraska's lush grasses could do for their scrawny mavericks.

The boom lasted 10 glorious years. Texas drovers found that their efforts paid off in extra $20 gold pieces when they bypassed Dodge and moved north to the Platte. Kansas was fast being tamed by homesteaders and law and order. But Ogallala and the Indian lands to the north were wide open to the trail boss who had enough guts to push on to this untamed frontier.

Ogallala was huddled up in one small block

south of the tracks. Space oozed out on all sides,

10

the horizon broken here and there by at least a dozen

calico-colored herds of longhorns waiting to be

shipped or sold. During the long winter months, the

town was as peaceful as the most respectable of communities. But come the first big herd in June and

the tranquillity erupted into a free-for-all.

the horizon broken here and there by at least a dozen

calico-colored herds of longhorns waiting to be

shipped or sold. During the long winter months, the

town was as peaceful as the most respectable of communities. But come the first big herd in June and

the tranquillity erupted into a free-for-all.

At Bill Tuck's "Cowboys Rest" the glasses clinked all night. The most famous of the town's spread of saloons, it offered everything but rest to the rawhide just off the trail. On the right was a rude pine bar where a man could wash away four months of Kansas dust in one swallow of redeye. To the left was a string of tinhorns ready to help the cowboy ease the load of his poke. To the rear stretched a hundred feet or more of dance hall where Big Alice and her girls held court.

Sheriffs were a dime a dozen. From the time that the office had been created in 1874, no less than six had chosen a more peaceful profession by 1878. One, Barney Gillan from Texas, felt it was his bounden duty to protect the drovers, not the town. He got mixed up with Print Olive in the burning of two homesteaders, but skipped the state before treated to a necktie party. Another would-be peacemaker was once chased out of town by a Texas crew on a frolic.

DePriest was a Texan, too, but he more than satisfied the city fathers' needs. It was true that he let the town run wide open. As far as he was concerned, drinking and gambling and girling were all right. Nor did he take exception to the boys when they fired their pistols in the air. This was only harmless sport. But let one point his six-gun at him or try to take over the town, and it was another story. When word went out that Mart and his side-kick, Hughes, were on the prowl, Ogallala quieted down considerably.

When the sheriff couldn't keep the boys in line, Bill Tuck was more than ready to step in. He kept a sawed-off shotgun behind the bar at all times as an equalizer. It came in mighty handy when a tinhorn hombre by the name of Bill Thompson shot a glass out of his hand after an argument over Big Alice. Though three of his fingers were severed, Tuck grabbed the shotgun as the gambler walked out of the door and loaded him up with a case of lead poisoning that was a long time a healing.

Law and order also came at the Winchester-toting hand of Judge William Gaslin. Ten years was his standard sentence for horse stealing. Those guilty of worse had a date at Boot Hill. The first time he held court in Ogallala, "every man in the county was on the jury."

The town continued to grow as the herds moved in. Besides Cowboys Rest, there was the Crystal Palace and a batch of other saloons. The block also boasted the Ogallala House, a general store, shoe store, courthouse, and the "most substantial jail west of Omaha." Across the street was the newly constructed Spofford House where trail boss and buyer culminated thousands-of-dollars deals with a handshake and a slug of toddy.

Ogallala and the cattle business were booming. Longhorns spread out over "God's greatest pastureland", munching the short grass left by the disappearing buffalo. The Indians had fought their last at the Little Big Horn, and much of their old hunting grounds was now open to grazing. Big spreads like the Bosler Brothers, Moore Brothers, Coad Brothers, and others raised (continued on page 32)

11

the NAME'S THE THING

It's no wonder that there s confusion; finny clan has more aliases than Capone Test yourself by giving the popular Nebraska name for the fish species shown hereWHAT DID YOU catch last summer when you took that fishing trip to one of the many rivers, lakes, or streams in Nebraska? Was it a sheepshead, jack fish, calico bass, shovelhead, or dogfish? Yes, these are Nebraska fish, all right, the drum, northern pike, black crappie, sturgeon, and bowfin. Like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, they stand ready to confuse the uninitiated.

Imagine a beginning fisherman being told by an old hand that he had landed a sheepshead. It would be difficult to get enthused over such a catch, especially if the novice thought only of the gory sheep's remains instead of a fish named correctly the drum.

Many incorrect common names are derived from

a fish's color, his choice of habitat, and the way his

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

body is shaped. The catfish family is an interesting

example. A large channel catfish does not always

exhibit spots. When he does, he's called a spotted

catfish, but when the spots are missing, he's tagged

as a blue. The blue cat is usually whitish in color

and is therefore called the white catfish. The name

white catfish is sometimes applied to a young channel cat which has a whitish color.

body is shaped. The catfish family is an interesting

example. A large channel catfish does not always

exhibit spots. When he does, he's called a spotted

catfish, but when the spots are missing, he's tagged

as a blue. The blue cat is usually whitish in color

and is therefore called the white catfish. The name

white catfish is sometimes applied to a young channel cat which has a whitish color.

The yellow or mud cat is really the flathead catfish. He turns yellow in certain environments and in deep, slow-moving holes he looks muddy. But his name is very descriptive since he has a pronounced flat head.

All the confusion isn't confined to this one family, however. The paddlefish is not even a member of the true catfish family, but to many fishermen he is known as the spoonbill cat. This name is an obvious one because his bill-shaped nose looks somewhat like a spoon.

Take the silver bass, for instance, that is if you could. No such fish exists and when a fisherman says he has creeled one, he probably has caught a white bass, drum, or goldeye. Largemouth and smallmouth bass, found in most Nebraska lakes, are often mislabeled black bass. Although these two are called bass, they belong to the sunfish family. The white bass is the only member of the true bass family in the state.

Bullheads, of which there are two kinds in Nebraska, are mistaken for each other. Few yellow

MARCH, 1963

13

bullheads exist here, but the black variety often

takes on a yellow color from their habitat and therefore the name, yellow bullhead.

bullheads exist here, but the black variety often

takes on a yellow color from their habitat and therefore the name, yellow bullhead.

Color is a poor way to distinguish between species, since water conditions play such an important role in the coloration. The white sucker is called the black sucker because he turns dark in turbid water. Fishermen will swear that the white sucker they caught in clear water just can't be the same thing as the black specimen they just pulled out of muddy water.

Another familiar name to the fisherman is the skipjack. Again, such a fish does not exist. The angler has really caught a goldeye or a gizzard shad.

Confusion also arises in the case of the misnamed

walleye pike. This species is a walleye and not a

14

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

pike. Topping this is the fact that the walleye is a

member of the perch family. The old northern pike

is stuck with the handles jack fish or snake. Snake

is especially appropriate because of the slim, elongated body sporting a mouthful of teeth.

pike. Topping this is the fact that the walleye is a

member of the perch family. The old northern pike

is stuck with the handles jack fish or snake. Snake

is especially appropriate because of the slim, elongated body sporting a mouthful of teeth.

One of the most common names for the black crappie is calico bass. It's easy to see where he got his name. The pattern on the fish actually looks like a piece of grandmother's calico.

Carp are usually carp to almost everyone. But he answers to German carp, leatherback, mirror carp, and general nuisance to some fishermen. He's a tough fish that can survive almost anywhere and usually does.

Some of the other colloquial names for our freshwater inhabitants are grass pike for grass pickerel; fresh-water cod, ling, eel pout, or pocket eel for the burbot; and sun perch or sunfish for the bluegill.

Fish have now and probably always will have more than one name. There's just no getting around it. The only way to have one name for each fish is to use the scientific nomer. But can't you imagine some angler telling his wife he caught a Micropeterus salmoides (largemouth bass) and three Lepomis macrochirus (bluegill)? Maybe we'd better remain confused and leave these flashy names to the men who know what they mean.

THE END ANSWERS 1. Whiter bass 2. Drum 3. Carp 4. Largemouth bass 5. Bluegill 6. Northern pike 7. Short-nosed gar 8. Paddlefish 9. Sauger 10. Walleye 11. Channel catfish 12. Rainbow trout 13. Brown trout MARCH, 1963 15

CRAZY FOR COTTONTAILS

by Neale Copple Mention rabbits and Vince Blinde just naturally flips his corkTO VINCE BLINDE, cottontails spell "g'demptes rabbit and sour cream gravy". But you don't have to understand his kind of talk to enjoy it. It simply means good eating in Clay County language. And finding Brother Cottontail to do the g'dempting to adds up to good hunting, no matter where you do it.

The Lincoln hunter has an eye for a cottontail and a stomach for what can be done to one by the right cook. He, like his thousands of counterparts in every corner of the country, refuses to relegate bunny hunting to the kids and their popguns. To him, tracking the cottontail is a challenging job and the shooting great sport.

Quail hunters have their own secret hedgerows and their private coveys. Pheasant enthusiasts talk in hushed tones about their particular cornfields. And the cottontail connoisseurs, who outnumber any other single hunting breed, know their hunting grounds as well as their fluffy-tailed prey.

Vince, for example, found his bunny-hunting heaven by accident. He explains that he was looking for a new spot to shoot and had wandered onto a little-used dirt road near the Blue River. It was fall and the road was mud. Vince slid to a stop at the top of a hill and tried to figure the straightest route to the nearest gravel road. Looking around, he spotted a good patch of sumac, the red heads stuck out against the blue autumn sky.

"Good spot for a bunny," he thought, and being a bunny hunter, he hunted.

He had kicked out two cottontails, missed one, and shot the second, when he realized that patch of sumac hid the sweetest little rabbit ravine he had ever seen. A cornfield stretched into it from the north. Fingers of a wheat field reached down the slope from the south. Between the fingers of wheat and in the gullies in the corn a smart farmer had planted grassed waterways. These served to hold the soil, but any respectable rabbit hunter knew they hid grain-fat cottontails, too. At the bottom of the ravine, thickets of wild plum and willow provided the ultimate in cover.

In spots like this the world over, hunters practice an art that goes back to the days when it was literally worth one's life to get caught poaching a hare from an Old World preserve.

In every kind of cover and every kind of terrain, Brother Cottontail can offer a special and different kind of target. In thick grass, such as that found by Vince in the farmer's waterways, the rabbit becomes an unpredictable trapshooting (continued on page 33)

MARCH, 1963 17

the MIGHTY MISSOURI

THEY CALL him the Mighty Missouri and mighty he is, a giant of the land who has toyed with men's destinies almost since the beginning of his turbulent career. Born of a violent fusion of water and ice, the river has lashed and gouged his way down NEBRASKAland's ragged eastern side, determined to play the starring role in shaping the state's heritage.

The Missouri has done just ^that ever since he broke his icy chains in the nortA and came spilling across the plains to his wedding with the Mississippi. He was an unpredictable young buck 50,000 years ago and no wonder. Couped up in the glaciers of the Pleistocene Age and relegated to flow his dismal course to Hudson Bay, he was eager to get a taste of life. Once strong enough, no bonds could hold him and he lit out for points south. Only in recent years has the wild wanderer mellowed enough to make him tolerable to folks who have desperately wanted to make his acquaintance.

The Indians never cottoned to his shenanigans. To the Sioux he was Minisose, the turbid water. Another tribe had his number, giving him the tag, Nishy-dsi, the place to be drowned at. Others called him Mad River and Father of Floods. Ultimately he settled for Oumissourit, Indian for abundant with people. When he accepted Missouri, the brazen buck of old was finally ready to settle down.

Whatever he was called, everyone faced him with respect mingled with fear. Audubon said of the mighty river, "All is conflict between life and death. The banks are falling in and taking thousands of trees and the current is bearing them away from the places where they have stood and grown for ages ... All around was the very perfection of disaster and misfortune."

Pierre DeSmet painted a dramatic picture of the untamed torrent: "Steam navigation on the Missouri is one of the most dangerous things a man can undertake. Gigantic trees stretch their naked and menacing limbs on all sides. You see them thrashing in the water, throwing up foam with a furious hissing sound as they struggle against the rapid torrent. I fear the sea, but all the storms and other unpleasant things I have experienced in four different ocean voyages did not inspire me with so much terror as the nagivation of the somber, treacherous, muddy Missouri."

Others pretended not to fear him. In 1852, Captain Francis Belt was piloting the Mormon laden

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Saluda upstream. At one point, the current became

so strong that it seemed he would not be able to go

on. Belt ordered full steam ahead and said that he

would "round the point or blow her to hell." The

explosion scattered bodies and bits of wreckage on

both shores.

Saluda upstream. At one point, the current became

so strong that it seemed he would not be able to go

on. Belt ordered full steam ahead and said that he

would "round the point or blow her to hell." The

explosion scattered bodies and bits of wreckage on

both shores.

Anyone who has tried to ride this sunfishing bronc respects his strong cross currents. When he gets his dander up he swishes his current from one side of the river to the other. And for sheer orneriness he sets himself spinning in rampaging whirlpools. During one 61-year period, he buried 450 steamboats worth $10 million beneath his swirling death traps. Skin divers are only now beginning to explore the bottom for sunken treasures buried there.

South of his confluence with the Platte, the Missouri shoulders through 200-foot-high bluffs about two miles apart. But he doesn't let them push him around. On a whim, he'll change his course and run through the first valley that pleases him. When he impatiently changes beds, he remembers to leave a calling card to make sure you know he has been there. He does this by dropping intricate sand formations in his path. The Mighty Mo's biggest laugh came when Lewis and Clark mapped some of these sand formations out in minute detail because they thought they were ancient fortifications.

Even funnier was the trick he played on 20th century highway engineers. They had gone to great trouble to put a $2-million bridge across his path. About the time they were standing back to admire their creation, he up and cut a new channel, leaving the bridge high and dry. It was such a good joke that he didn't much care when they began dredging his innards and forced him to come back under the bridge.

Probably some of his best bits of horseplay were pulled on early river-boat captains. Too often they would find islands in the river where there had been none a short time before.

Though he couldn't be called a thief, he was the next thing to it. Each year he hauls 9,000 acres of choice farmland away and dumps 500 million tons of alluvial soil into the Mississippi. Volcanic ash carried all the way from the Yellowstone is the substance that forms the Mississippi Delta. The ash hardens when it meets the salty Gulf waters and drops to the bottom.

You won't find many people calling this maverick pure, but pure he is. Near the turn of the century, a test was made of water from different parts of the globe to see which would continue pure and wholesome for the longest period of time. Water from the Mississippi just below its confluence with the Missouri was the winner, hands down. Undoubtedly the Missouri was responsible for this judgment. He lends not only the purity of his ash-laden waters to the Mississippi, but after the confluence, the river takes on the Missouri's raging, turbulent nature. After seeing this sudden transformation, many of the pioneers figured that from the confluence south, the river ought to be called the Missouri, or if the name Mississippi was retained, it should be applied all the way from the Gulf to the Missouri's headwaters.

MARCH, 1963 19

Even with all of his gyrations, the river served as the earliest highway into the West. He was discovered in 1673 by Marquette and Joliet. In 1682, La Salle was told that the Missouri was spawned in a range of mountains with the sea close on the other side. This set off a siege of explorers looking for the "Vermillion Sea" and "Great Lakes of the West". Their quest was a route to China and its legendary gold mines. If that's what they figured, it was all right with the Missouri. He would fool them as long as they cared to be fooled.

In March 1702, 17 Frenchmen established a fort along the Nebraska-Iowa border. They seem to be the first organized white group to navigate the Missouri's turbulent waters. In 1714, Etienne Veniard du Bourgmond navigated and charted the river as far as the Platte. On his second expedition in 1723, the explorer established Fort Orleans, possibly the first west of the Mississippi. Pierre Gaultier de la Varennes de la Verendrye and his sons gave a lifetime to the river in search of the Western Sea.

The secret the Missouri kept so well was finally exposed by Lewis and Clark in 1804. Instead of a lion they discovered a lamb, the river's Montana headwaters no more than a freshet. China was an ocean away, an ocean they discovered after many miles of walking down the Continental Divide. Exploded forever were the myths of the Vermillion Sea, a Southwest Passage to China, the Great Lakes of the West, and Coxe's description of the Rocky Mountains as a ridge of hills passable in a half day.

Even though Lewis and Clark disproved all the old legends, the explorers had triggered an exodus. First came the mountain men to rob the river's wilderness of its furs. Following their mocassined path were the settlers, timid at first, then bold with the lust of conquering new frontiers. Towns bristled up on his banks and he was on the way to being tamed. But not without the Mighty Mo giving everyone fits who tried to meddle in his affairs. After all, he had had his way for thousands of years.

Giant dredges sucked at his innards, making him keep his path clear. Huge pile drivers rammed stakes in his sides to make him follow the straight and narrow. Dikes were thrown up at his many oxbows to keep him from meandering. Massive dams were built to control his flow, his vibrant pulse beat sent humming through huge generators to light large city and small. Though there's still more to be done, the mighty river has been shortened by 173 miles. But even he would have to admit he likes the streamlined face lifting.

Today the Missouri is the central figure in Nebraska's booming move forward. Commerce, power generation, flood control, and recreation have all blossomed because the Missouri could be counted on to make it so. He has come a long way from Ice Age marauder to Space Age benefactor. If you asked him, he would probably admit that that's what he had in mind all of the time.

THE END MARCH, 1963 21

the LADY'S A SPORT

Mine has been a love affair with the outdoors since pigtail days Oar reader writes...THERE HE was, snared in one of my traps, and

before I could do anything about it, the little

black-and-white devil let me have it smack

in the middle of my eyes. Once I recovered from

the initial shock, I evened the score with my .22, if

you could call being skunked even. There would

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

be no school for me today, and maybe a couple of

more if I couldn't get rid of the horrible smell of

the dead skunk.

be no school for me today, and maybe a couple of

more if I couldn't get rid of the horrible smell of

the dead skunk.

All this happened a long time ago when I was a devil-may-care sixth grader going to country school near Chambers. It wasn't the first time I'd been ostracized by both teacher and parent. Nor would it be the last for a girl who loved Nebraska's outdoors as I did. It's an affair that's still going on, one that has lasted a lifetime.

I began trapping when most girls my age were supposed to be playing with dolls. Though not the tomboy type, it seemed only natural to cash in on all the game that abounded between my home and school. My trap lines payed off very well, earning me extra spending money from grade school through high school.

Like any woman, I always dreamed of having a fur coat. What better way to get one than to trap my own furs. Unfortunately, the dollar value of the pelts always tempted my practical side and I have never got around to getting one. But I'm still dreaming and may get one yet.

Some would say that a young girl in Atkinson High School's class of '29 should have had other interests besides trapping and hunting, especially one that planned to be a school teacher. I had all of the normal interests of a teenager; trapping and hunting were bonuses.

With teaching certificate in hand, I was ready to pass on all my wordly knowledge to the young people attending country school near Star. For a while I boarded at the home of a friend, now Mrs. Dick Curran of Omaha. Her dad let me run a trap line on his farm, and I soon had my girl friend as enthused over trapping as I was. She went out with me almost every morning, and once we had the day's take home, she held the legs of the animals as I skinned them out. It wasn't long before we had a nice cache of muskrat, mink, skunks, and badgers ready for market.

Needless to say, my students learned more than the three R's. My enthusiasm for the outdoors naturally became theirs, and I soon had many of the boys and girls in the district either following their own traps, hunting, or at least taking a closer look at the wildlife that abounded around them. The first questions that inevitably greeted me every morning were, "What did you get this morning? How is the hunting?" With this kind of atmosphere, it was an easy chore to teach the more normal courses in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

The men in my life have played an important part in my love affair with the outdoors. My dad first introduced me to its beauties on many a hunting trip when I was only a child. When I married fellow school teacher Duane Carson, I had a new hunting and fishing partner. Through the years, we've been throughout Nebraska and other states in search of game.

After teaching for 17 years, I decided to retire so I could devote full time to my other hobbies. Fishing and hunting, of course, always come first. They've taken the place of trapping. I get a kick out of playing the piano and square dancing, too. And as proof that a woman can be an ardent outdoorsman and still be a woman, I operate a beauty shop in Chambers. Every now and then I get a call to substitute at one of the schools around Chambers, so there's never a dull moment.

My 12-gauge shotgun is great for birds, but I switch to the .22 rifle for squirrels and rabbits. The scattergun is all right for grouse and pheasants, but it destroys too much rabbit meat.

Once when pheasant hunting a willow thicket on South Fork Creek, I suddenly heard a rattle overhead. Twigs fell around me and I heard a barrage of shots. I headed for (continued on page 32)

MARCH, 1963 23

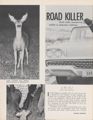

ROAD KILLER

Death stalks unsuspecting wildlife on Nebraska's highways by Bob Havel District Game SupervisorIT CAN happen so quickly that you don't have time to depend on your reflexes. A deer suddenly appears out of nowhere, frozen in the bright beam of the car's headlights. There's little space to stop but you slam down on the brake anyhow, hoping somehow to avoid the sickening thump that'follows. In a moment it's all over, the front of your car ruined and the deer dead.

Accidents such as this are becoming more common every year as Nebraska's deer herd expands

in numbers and range. State hunters set a record

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

for deer harvested during the 1962 rifle season.

Motorists also set a new mark with 626 deer fatalities on the state's highways. In the past three years,

1,281 have been killed by automobiles.

for deer harvested during the 1962 rifle season.

Motorists also set a new mark with 626 deer fatalities on the state's highways. In the past three years,

1,281 have been killed by automobiles.

Pheasants, rabbits, raccoons, and other game birds and animals also come in for serious road-kill losses. Although they do not seriously affect game populations, they do constitute recreational loss; game that would be better utilized in the hunter's bag.

These accidents are costly to motorists. A collision with a deer often means replacing the entire front end of a car and can easily cost $400. One spectacular accident in 1962 ran up a $600 bill for three car owners. The first car hit the deer, throwing it into the path of the second and the third. The damage to the first car came to $300, the second, $200, and the third slightly over $100. Accidents with a pheasant can mean a new windshield at a cost of around $100.

With deer now in numbers to support a state-wide season, more accidents are bound to occur. Several eastern counties are now reporting highway kills for the first time while the number lost in other counties is increasing. In 1960, only 65 counties reported highway kills. In 1961 the number increased to 79, and in 1962, 88 of the 93 counties had deer-automobile accidents.

Some of these road kills could have been avoided. In many instances the car hits the second or third deer crossing the road while the driver is still watching the first. When one crosses a road there are often others in the group. Blowing the horn may not cause the deer to turn back and bright lights often only make him freeze in his tracks. If there are deer crossing the road, reduce speed until the vehicle can be stopped easily. If possible, pull over and wait for the deer to cross.

Highways bordering stream bottoms or canyons usually take a steady toll of deer. Special care, particularly at night, should be taken here. Signs reading, "Deer Crossing Area" and "Watch For Deer On Roadway", mean just what they say, so heed them.

Greatest deer losses occur during the spring and fall, with November and May the peak months. Last year November highway losses accounted for 153 animals and May, 74. Some 35 does killed in auto accidents carried 53 unborn deer, indicating that the destruction of one doe may mean the lives of three.

Pheasants are particularly susceptible in the spring and winter months. During the winter they frequent roads during periods of heavy snow in order to obtain gravel, making them easy prey. In the spring months roosters, thinking only of their lady loves, have little fear of automobiles. Some have even been known to defy cars when meeting them on the road. Birds which have been congregating in heavy cover during the winter spread out in the spring and are often hit while crossing roads on their way to nesting areas.

Muskrats are an early spring problem to motorists. The young of the previous spring are kicked out by their parents and wander in search of a new home. Often this is their first experience with cars and they fall easy prey to a speeding motorist. Young beaver are also vulnerable. Rabbits are killed mostly at night when, while crossing a road, they freeze at the approach of headlights.

The prevention of game losses occuring on Nebraska highways is a difficult task. A reduction can come only if care and caution is taken by drivers. Remember the deer or pheasant you save on the highway means hours of enjoyable recreation during the hunting season.

THE END MARCH, 1963 25

NEBRASKA BULLETS

WHEN HE was a youngster growing up on his parents' farm near Brock, J. W. Hornady was interested in hand loading. Carefully pouring lead into a mold to make his own bullets, he dreamed of the day he would have a real outfit like the fancy ones pictured in a catalog. Today, he has the fanciest one going, a factory turning out 150,000 bullets a day. Instead of a simple mold, Hornady has six machines thumping away, each turning out a bullet every second.

Hornady's dream didn't take place overnight. Between his days on the farm and his present Grand Island operation he worked at a variety of jobs. While attending the University of Nebraska as an engineering student he earned extra money molding pistol ammunition for the highway patrol. But the depression was on and he left school to strike out on his own. But while operating a retail dairy business, selling printing supplies, and working in a laundry, Hornady's love for guns and shooting remained.

In 1942 Hornady moved to Grand Island to work

at the ordinance plant to train guards as sure shots.

After the war he started a sporting-goods store in

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Grand Island, selling, among other things, hand-loading components.

Grand Island, selling, among other things, hand-loading components.

Besides being an avid hunter, Hornady was a perfectionist and he wasn't pleased with the bullets on the market. But instead of complaining, he made his own. His first shop was in his basement and he had only hand tools. But he made a better bullet. Soon Hornady was out of the sporting goods store and manufacturing his own. First came a rented building in town. A few years later a modern plant was built. Even that was too small and two additions were added. Today Hornady heads one of the largest bullet manufacturing companies in the country. His products are known the world over, being used on everything from rabbits to elephants.

"The trouble," says Hornady, "is that I don't have enough time to reload and shoot any more. Most of the time I have to ask one of the men at the plant to load for me."

It isn't quite as bad as that, though. Stretched out in the lobby of his plant is a rug made from a 900-pound Kodiak bear he shot a few years ago. Naturally he used one of his own bullets, dropping the monster at 200 yards with one shot. Other big-game trophies adorn the wall, all felled by Hornady and his bullets.

Before the year, Hornady's company will turn

out over 22 million bullets. They'll range in size

from the tiny 40 grain, .22 caliber cartridge that

MARCH, 1963

27

weighs about one-eleventh of an ounce to the 500

grain .458 capable of dropping a charging elephant

in his tracks. There are 67 different sizes in the

line with new ones added as the demand arises.

weighs about one-eleventh of an ounce to the 500

grain .458 capable of dropping a charging elephant

in his tracks. There are 67 different sizes in the

line with new ones added as the demand arises.

The equipment is some of the most modern in the world. Thin strips of copper alloy are fed into a double-action blank-and-draw machine. Out the other end comes the cup for the start of a bullet. It is drawn three more times to the proper length. At the other end of the room is a machine extruding the lead wire that goes into the jacket. Somewhat like a toothpaste tube, the machine squeezes out the lead as it is wound on wooden spools.

Once this is done the two components are put into the same machine where the lead is inserted and seated and the bullets are shaped. The completed bullets come out the bottom as if from a candy machine. From there they go to a revolving drum which removes the excess oil and on to another containing ground corn cobs for polishing. In no time they are on their way to the four corners of the world, loaded into cartridges, and used on everything from targets to big game.

But there is a lot more to turning out a quality bullet than putting stock into a machine and collecting the finished product. Days, months, and years of work go into research and production methods. The number of bullets produced means nothing if they aren't of the highest quality.

"Hand loading is done for two reasons," explains Hornady. "You can cut the cost of ammunition from a third to half by doing it yourself. But, just as important, you can load ammunition for a specific purpose and to suit the individual rifle. Actually, each rifle is different. One will shoot a particular load accurately where another of the same make and caliber won't.

In order to assure extreme accuracy, Hornady

has his own toolroom turning out the dies to his

precise specifications. Hornady pioneered the use

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of tungsten carbide in swage dies. This is the hardest material made by man and the dies wear from

50 to 100 times as long as those made of steel. To

further insure accuracy, dies are shaped by an

electrical discharge machine which cuts with a high

frequency electric current.

of tungsten carbide in swage dies. This is the hardest material made by man and the dies wear from

50 to 100 times as long as those made of steel. To

further insure accuracy, dies are shaped by an

electrical discharge machine which cuts with a high

frequency electric current.

Hornady and his 25 employees are all on a first-name basis. He is a member of the company bowling team. One of his employees is 82-year-old Roy Steen, his father-in-law, who has worked for Hornady for 15 years. The chief engineer, Chuck Schreiber, started with Hornady after the war in the sporting-goods store, then later served as a machine operator when the company was first formed.

One of Hornady's pet projects is his underground 200-yard-long concrete test tunnel. It sports electronic equipment sensitive to a millionth of a second to measure muzzle velocity and other ballistic performances. Hornady does some of the testing here but most is done by Ruben Hayes who first worked for him as a press operator.

As complicated as his operation looks, Hornady makes it sound simple. "There really isn't anything difficult about it at all," he explains. "Rather, it is a series oi elementary problems put together."

You can be sure that Joyce Hornady will lead the way. Anyone who can transform the crude hand loader of a boy into a precision bullet company is already way ahead of the game.

THE END

PLAY IT SAFE

The games dangerous only when you forget boating s common-sense rulesLAST YEAR more than 18,000 boats plied Nebraska's impressive system of recreation waters. Everything from whopping-big Lewis and Clark Reservoir down to the smallest of the sand-pit lakes got in on the action as more and more outdoorsmen climbed aboard the booming sport.

Nor is the boom about to stop. More boaters are using state waters than ever before. Though few waters approach being congested, the increased traffic puts added responsibility on every boater to help keep the accidents down.

Six lives were lost in boating accidents here last year. Considering the number of deaths per boat to the number of deaths per car, this figure takes on a new significance. There was one death for each 3,000 boats compared to one for each 2,187 cars. Since we use our cars 27 more times than we do a boat, it would appear that the sport is a dangerous game.

Is boating so hazardous? Not really. It is the

man who does not use his head that can turn an

30

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

enjoyable activity into a dangerous pastime. Education and proper precautions can prevent accidents.

Five of the year's six deaths would never have occured if the victims had been wearing life preservers.

enjoyable activity into a dangerous pastime. Education and proper precautions can prevent accidents.

Five of the year's six deaths would never have occured if the victims had been wearing life preservers.

Handling should come in for special attention. A boat does not drive the same way as a car, no matter what some might say. There are many differences that must be learned. A safe speed for an automobile is not a safe speed for a boat. Thirty miles per hour must be considered high speed for the cruising boater. This speed can be uncomfortable and dangerous for the skier. Maneuvering is tricky and a sharp turn can capsize some boats. Floating debris is hard to see and hard to avoid.

The difference that the beginner has most difficulty in learning is that cars and boats are not steered the same. A car is turned by a lateral movement of the front end in the direction of the steering wheel. When the steering wheel of a boat is turned in one direction, the stern moves laterally in the other. Steering a boat is something like steering a car in reverse. If a tiller is used, it is moved in the opposite direction of the turn.

Remember that your boat does not have brakes. To stop suddenly, you must shift the engine into reverse. This may stall the engine or jam the transmission. To avoid a highway accident, you slow your car. A slowed or stopped boat is at the mercy of wind and currents, often carrying it to the accident you are trying to avoid. Minimum speed must be maintained for maneuverability. Slowing a boat too quickly can change its handling characteristics.

Take your new outboard to the water and practice steering, stopping, and other movements until they are as natural to perform as similar maneuvers are in your car. Learn to judge the distance needed to steer around objects by placing a life preserver in the water. Do this in open water where there is no danger of colliding with other craft.

You can avoid most of the more common accidents by using your head. Don't stand up in a shallow boat or sit carelessly on a slippery deck. If someone falls out of your boat, slow down, then think before you act. A line or life preserver tossed near (not at) the victim should do the trick. If not, swing the boat around and move slowly upstream or upwind toward him. Never back toward him or bring the boat up so that the wind may drive the craft into him.

Proper maintenance can help to prevent mechanical breakdown. Check your fuel supply. Only neglect could cause a person to be stranded in deep water because he ran out of gas.

Meet the wakes of other boats head-on. A wash that strikes your boat from the rear can swamp it or sweep it away at high speed completely out of control. A strong wake can even turn a small boat end over end.

If your boat is swamped, all passengers should stay with the craft and not try to swim ashore. Drownings have occured because the swimmer misjudged his ability or the distance involved.

Nebraska's boating laws have been designed with one primary purpose in mind—safety. Heed these rules and you'll be sure to enjoy all the fun that this booming sport can offer. Knowledge of your boat and state laws, common sense and courtesy, these add up to the makings of a safe boater.

THE END MARCH, 1963 31

THE LADY'S A SPORT

(continued jrom page 23)thicker cover fast. That's the nearest I've come to being shot in a lifetime of hunting.

Bumpy, my dachshund and spaniel mixture, looks like anything but a hunting dog. But she can more than hold her own as proved on a recent duck-hunting trip. When the first duck hit the water, she splashed in and swam out to get the prize. The duck was almost as large as she was, but Bumpy managed to stay afloat and brought it in. We suspect that we have a new breed of retriever.

Behind my house are two ponds fed by artesian wells. One dishes up frogs and bluegills. The other holds carp. It is a simple matter to walk out the back door, gig a carp or a few frogs, fish for bluegills, or if the season is open, walk a bit farther and shoot a few squirrels.

Duane and I take our fishing seriously, chancing the worst of weather to bring home fat creels. Actually, we've found some of our best angling when the sky was ready to pour buckets. One early spring day, Duane and I fished at Willow Lake. There were some clouds, but we didn't think it would rain. It began to pour down. We were wet and cold, but the fish began hitting like mad. The two of us were the only ones eager enough to stay out, but we had a really memorable day's sport. It took hours to warm up afterwards.

Many outdoorsmen overlook uses that can be made of game. All of the pillows in our house are made from duck and goose down and I use duck-wing dusters to brush away lint. Skunk oil works great for chest rubs or boot dressing. Of course, we've always got a supply of wild meat. We don't really save money by eating game, but its taste can't be beat and just about pays for the expense of rifles, fishing rods, and other equipment.

My love for the outdoors could probably best be expressed in a recent western trouting expedition. I enjoyed the beautiful scenery as much as tangling with the abundant 15-inch trout. Maybe that's why Duane and I enjoy hunting and fishing so much. It's not how many fish you catch or how many ducks you shoot that makes a good trip. It's the enjoyment of being in the open and seeing the blossoms of spring and the changing colors of fall. These things are the highlights of the hunt. Any game taken is a bonus.

Strange as it seems, Duane and I have never been able to pass on our enthusiasm of the outdoors to our daughter, Patricia. But we have hope. Her three boys show all of the curiosity that I had when I was young. John, the oldest, already has that far-away look in his eyes and that special spark when a big one is on his line. I can see myself in the seven-year-old, a youngster eager to explore another niche of the outdoors. If he's like me, his will be a love affair that will last a lifetime.

THE ENDOGALLALA

(continued jrom page 11)thousands of head in the panhandle range. Close to 100,000 head carried the Ogallala Land and Cattle Company brand alone in 1880.

But the boom was about to bust. Grangers plowed the land, blocking the trail north. Settlements mushroomed along the Republican and other key waterways. By joining together, the frontier farmers were able to turn aside the herds. Those with a hankering for green stuff built corrals to hold herds that had trespassed land claims and forced the trail bosses to pay ransom to get their cattle out and on their way.

Texas fever swept over the plains in 1884 to add to the cowmen's woes. It first appeared in a herd near Ogallala and spread like greased lightning to the rest of the herds. Those ranchers who had introduced blooded lines into their outfits joined in the battle to halt the drives. This was the final blow that doomed the business.

With the Texans gone, Ogallala began to mellow. Big Alice and the rest of the girls packed their war sacks and headed back to Omaha and Cheyenne. The tinhorns, with sparse few rawhides to clip, looked for new areas to ply their ancient trade. Bored by the unnatural quiet that had settled over the town, Bill Tuck sold his lucrative Cowboys Rest and headed south. The Congregational Church had been organized the winter before and Bill figured the competition was too tough.

But ask any man from Ogallala where Nebraska's cowboy capital is and he'll be quick to take you on the grand tour. You won't have to duck the shots of some redeyed rawhide on a frolic. Nor will you have to worry about the sheriff being run out of town. But the memories are there. So are the stories and legends. Out on the range prized beef roam, and booted feet line the brass rails. Ogallala's cowboy country, all right, a part of NEBRASKAland's Wild West heritage.

THE END OUTDOOR NEBRASKA 32

CRAZY FOR COTTONTAILS

(continued from page 17)delight. On bad weather days, particularly, he crouches in the grass, refusing to move until he's all but been kicked in his cotton tail. Then he scampers from underfoot, out of his hiding place, and zigzags across the open spaces. There is no sky for background as there is in most bird hunting. There is only ground, often the color of the target, and a scampering skittering scalawag who can make a good shot wonder if he is losing his eye.

In heavy cover, such as the plum thickets and willow bushes Vince found in his ravine, the cottontail makes quick shooting a necessity and a frustration since the hunter gets only a glimpse of his prey. In cornfields the bunny becomes more of a straight-on target, frequently confining his dash to safety within the space between two rows. However, even here the cottontail refuses to be predictable, changing rows just as the hunter has drawn his bead and taken his lead.

The elite of the cottontail connoisseurs are those who hunt with that almost ideal companion, the beagle. The dog usually does the work while the hunter relaxes, but you have never heard a baying beagle complain when he was on the line of a cottontail.

One of the rabbit's best known, but frequently forgotten traits is illustrated when the beagle goes to work. Cottontails do not head off across country as do jack rabbits. Mr. Cottontail confines himself to a relatively small area. When either dog or man disturbs him, he often scampers out along a well-known run that leads him sooner or later back almost to the same place. Since the beagle knows this, as does his master, the hunter waits while his baying companion chases the prey around the circle and back for a clear shot.

While the beagle and his gun-toting buddy may represent the elite in the field, their counterparts can be found in the kitchen—a good cook and a rabbit recipe. Vince and his recipe for g'demptes rabbit and sour cream gravy is only a sample. Brother Cottontail comes off well when treated like a young frying chicken. He can be stewed, braised, roasted, and just about anything else so long as it is done with the respect due a delicacy.

This may place a good many rabbit hunters in the meat-hunting category, but it's a little difficult to condemn any of them once you have tasted g'demptes rabbit. It was thinking about this frying-pan delicacy that lost Vince his ideal hunting spot. On his trip away from the ravine he was so busy worrying about his stomach that he forgot to look for landmarks near his river-valley cottontail paradise. He could see his mother-in-law, Mrs. D. J. Pope, of Sutton, transforming a cottontail into a connoisseur's delight.

For a man who loves bunnies on the run and in the platter as well as does Vincent P. Blinde, his loss of rabbit ravine was almost tragic. Time after time he traveled the valley country, looking for his almost-perfect spot. He was even known to slip away from the pheasant hunters to spend an hour or so in search of his own particular Shangri-La.

Vince found his bunny paradise as he had lost it. This time it was late winter, but the roads were equally muddy. He had slipped and slid to the top of a hill and paused to look for the nearest gravel road. Then, to the east, he saw a patch of sumac, lifeless against the late winter sky. He left his car in the mud and ran into the brush. He pushed through, ignoring a cottontail that scampered from beneath his feet. But all he could think of was g'demptes rabbit and sour cream gravy.

THE ENDCLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 DOGS Qo&UnRod AKC BLACK LABRADORS: Top hunting and field-trial prospects. Pups. Breeding stock. $50 and up. Proven sire available. Kewanee Retrievers, Everett Bristol, Valentine, Nebraska. Phone 26W3. DOG TRAINING TRAINING RETRIEVER and bird dogs: Gun-dog or field-trial dogs worked on pigeons, ducks, quail, and pheasants. Individual concrete ' runs, best of feed and care. Dogs boarded year-round and conditioned for hunting. English setter and Labrador stud service. Platte Valley Kennels, Route No. 1, Box 61, Phone DU 2-8126, Grand Island, Nebraska. FISHING FISHING PERMITS: On sale now at 1,200 agents throughout the state. "1963 Guide to NEBRASKAland Fishing" also available. Get yours now. MISCELLANEOUS GET IT TODAY: The Hungry Sportsman's Fish and Game Cookbook. Over 400 recipes. Includes mushrooms, frogs, etc. $1 postpaid. Eddie Meier, Box 3030, Scottsdale, Arizona.BOAT TRAILERS

Now there's a low loading Golden Rod Boat Trailer for easiest launching and loading... safest trailing. And there are Golden Rod trailers for every size of boat —all with the features you want for easier handling, easier pulling. See them at your marine dealer. Nebraska made for Nebraska needs DUTTON-LAINSON COMPANY Est. 1896 Hastings, Nebraska

notes on Nebraska fauna...

LONG-BILLED CURLEW

THE STICKLE-BILL, commonly known as the long-billed curlew, is one of the most fascinating birds inhabiting the Sand Hills. His unusual characteristics of an extremely long downward curved bill, eerie voice, and large size are known to many outdoorsmen here.

A member of the shore-bird clan, the curlew goes

by the scientific name, Numenius americanus. Shore

birds are generally characterized by long legs for

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

wading in marshes and lakes and long bills for feeding on insects and aquatic animals on and below the

surface of the water.

wading in marshes and lakes and long bills for feeding on insects and aquatic animals on and below the

surface of the water.

Though classified as a shore bird and looking like one, the curlew doesn't act the part. For instead of sticking close to open expanses of water, the curlew prefers to live on the grassy prairies of the central United States and Canada. The major range in Nebraska is the 20,000-square-mile area of the Sand Hills and the short-grass prairie region of the western part of the state.

The curlew is a large buffy-colored, long-legged bird. The best identifying characteristics are the bird's long downward curved bill and the bright cinnamon-colored wing linings as seen in flight. The body is a buff color with dark markings above and a buffy-to-cinnamon breast. When flying, the curlew looks as if he's hovering on the tips of his wings in seemingly effortless flight. In flight he looks as large as a duck, with his bill extended and legs trailing. Flocks fly in line or wedge formations and are further aids in identification. A long-drawn-out "curl-e-e-e-u-u" or a long "pill-will" will definitely identify the bird, even though the curlew can not be seen.

At one time, the curlew was very abundant throughout the grasslands of America and was considered an excellent game bird with fine table qualities. Old-timers tell of shooting curlew over decoys and selling them in the lucrative market for wild game in the early days of settlement.

As is noticed in other birds, there is a strong attachment between members of the same flock. During the market-hunting era, cries of a wounded or injured bird would bring the flock back, giving the hunters a chance to wipe out the entire flock. This often occurred.

With the plow's advance, the prairie gave way to agriculture, and the bird's natural habitat was drastically reduced. This and indiscriminate market hunting almost caused extinction of the species. But with protection from hunting and a gradual return of unsuited agricultural lands to grassland, curlew increased. The bird is now common over much of his former range in many western states, including Nebraska.

Curlews nest and rear their young in most areas of extensive grasslands. The nest is a simple hollow in the prairie, lined with dry grass. Nesting begins in late May, when a clutch of three or four buff-colored eggs with dark brown or lavender spots are laid. They are about the size of a pullet egg but are more pointed. Both parents assist in incubation. Thanks to his coloration, the incubating bird is almost invisible and is a tight sitter. When disturbed, the parent flutters away as if mortally wounded, trying to draw the intruder away from the nest. After taking to the air, the loud and vibrant "curl-e-e-e-u-u" call is given as the bird circles overhead.

Young curlews are walking behind their parents and trying to obtain their own food shortly after hatching. Each receives exceptionally good care from his parents, but is still vulnerable to the attacks of many enemies. The young bird has a small straight bill, the long downward curved shape is not acquired until he nears the adult size.

Food of the prairie-dweller consists mostly of various worms, grasshoppers, beetles, other insects and spiders, and berries. Because of this type of diet the bird must migrate south during the winter. At this time food includes that eaten by other shore birds, such as snails, crabs, worms and crayfish.

When living on the prairie, the curlew is very beneficial to man since he eats many grasshoppers and locusts. Studies have shown as high as 70 of these insects in a single stomach.

Migrating curlews arrive in the Sand Hills around the first of April and are last seen in mid-August. The bird is thus one of the earliest to start on the fall migration. This starts soon after the young are able to make the trip. The curlew winters from southern California and the Gulf states down to Guatemala and the West Indies.

In another month the curlew's familiar call will be heard over the Sand Hills, heralding the arrival of this shore bird that isn't a shore bird. He's an interesting and important part of the Nebraska scene.

THE END MARCH, 1963 35

FIRE STARTERS

Easy-to-make burners end sportman's top headacheNOTHING IS AS frustrating to a part-time woodsman as starting a campfire when the available tinder and fuel is wet. A match alone doesn't have the firepower to sufficiently dry and ignite the small shavings or twigs. That's when a fire starter is handy. Small and spoil proof, a few can be tucked into tackle box or hunting gear to remain until they're really needed.

Basically, fire starters are made of a porous material that will first absorb melted paraffin wax, and then serve as a wick to provide a ball of hot, long-lasting flame when it's lighted.

For safety's sake, melt the paraffin in a double boiler to prevent a flash fire while you're working. Roll a sheet of newspaper or paper toweling and tie it every two inches with string. Cut the roll into sections between the strings, soak the pieces in paraffin, and you're ready to start a fire anywhere, any time.

Acoustical tile ceiling block cut into ^-inch squares and soaked in wax is another good starter. So is a paper cup filled with sawdust, then soaked with paraffin. This is one of the best, the compact unit burning for as long as 15 minutes. A shotgun shell offers about two minutes of husky flame when it's split and lit.

A fire starter may seem a minor item, but it is one of the tricks of camping that fills a serious need, and will come in mighty handy when you depend on it most.

THE END