OUTDOOR Nebraska

25 cents BIG GAME CAMP

OUTDOOR Nebraska

December 1962 Vol. 40, No. 12 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. GREG SMITH, managing editor; Bob Morris, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard

BIG GAME CAMP

Put yourself where deer are in wilderness hunting bivouacBOTH THE bowhunter and the rifleman who plan

I to spend several days afield will benefit from

a wilderness-type camp. Here the spirit of the

hunt is intensified and prolonged. You experience

the thought-provoking magic of a campfire and discover the beauty of the outdoor scene. But best of

all, you arise only minutes before that prime dawn

hunting hour, step out of the tent, and your day has

DECEMBER, 1962

3

begun, while less hardy nimrods are still driving

sleepily to the field.

begun, while less hardy nimrods are still driving

sleepily to the field.

Constructing a comfortable camp isn't difficult. You can build it a few days or even a week before the hunting season opens. When selecting a site, look for a source of good water and plenty of dead timber for camp making and firewood. The site must be reasonably protected from wind and exposed to as much sunlight as possible throughout the day, since the fall air will be chill. When you find the spot, get permission from the landowner. You can do this at the same time you arrange to hunt on his land.

If you're a rank tyro at the camping game, spend some time beforehand in learning some basic knots and lashings. The shear, diagonal, and square lashings, the clove hitch, taut-line hitch, and the square knot are indispensable in putting up a wilderness camp.

Select suitable camping equipment, especially a good tent. An umbrella tent is fine, as is a regular wall tent. I prefer the explorer pattern, erected with an outside shear to eliminate inside poles. These larger units give you room to stand up.

For fire making, get a small bucksaw. It zips up a pile of wood in a hurry and safely. You'll need a good ax, well sharpened, to fell and trim the timber for firewood and camp furniture. Add a hand ax for light cutting, driving tent pegs, and to help dress out your big-game kill.

Since hunting hours keep you afield past dusk, you'll be doing many of your evening camp chores after dark. Use a gasoline lantern to light up camp. For moderate use, an electric lantern or a good flashlight may suffice.

For sleeping, down or Dacron-filled bags are the only really satisfactory ones to cope with the temperature. A suit of Dacron-insulated underwear as pajamas will team up with a medium-weight sleeping bag to let you sleep warm even if the temperature drops to zero. Forget an air matress for cold-weather camping. Instead, use a thick layer of dry grass, leaves, or straw.

Get a regular nesting camp cook set for cooking

gear. Buy yourself 400 feet of cheap V4-inch rope

for lashings and you're ready to start building camp.

At the camp site, cut a dozen poles about five

inches thick by 14 feet long. Take only dead timber,

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

these are needed for your tent crib, shear poles,

and game tripod. Select a bit of level ground, preferably on a small elevation, protected from the prevailing wind.

Clear an area four feet larger than the floor size of the tent, then plant a short post at

each corner of the clearing. Use three of the long

poles to enclose the back and two sides of the crib.

Lash the ends of these poles to the corner posts with

the ^-inch rope and a diagonal lashing.

these are needed for your tent crib, shear poles,

and game tripod. Select a bit of level ground, preferably on a small elevation, protected from the prevailing wind.

Clear an area four feet larger than the floor size of the tent, then plant a short post at

each corner of the clearing. Use three of the long

poles to enclose the back and two sides of the crib.

Lash the ends of these poles to the corner posts with

the ^-inch rope and a diagonal lashing.

If you've chosen an explorer-type tent similar to the one pictured, you'll need one set of shears to erect it. To make a shear, lay two of the 14-foot poles side by side, shear lash (continued on page 26)

GET THAT BIRD

by Carl W. Wolfe Game Biologist Over 170,000 shot pheasants never reach the hunter's bag. Follow these slick tricks and help cut down on wasteTO THE devoted game-bird hunter, the four words, "hit but not retrieved," spell disappointment to an otherwise enjoyable outing. These words spell cripple and indicate that many numbers of legal game birds are lost each season—birds which would have meant pride and enjoyment to the sportsman as well as tasty meals.

The number of ducks, geese, pheasants, and quail lost to hunters as cripples not recovered is difficult to determine. As many devotees of the ringneck will testify, this wary bird can carry a lot of lead. And every hunter at one time or another has been unable to find some bird he knows he hit.

From Nebraska's intensive research on the pheasant, seven years of continuous data from study areas in the south-central part of the state show that an average of 18 per cent of the total birds shot are not retrieved. This figure has gone to as high as 25 per cent in years of lower pheasant numbers.

Other states have found approximately the same crippling rate for pheasants. Michigan, for example, has assessed a loss of one cripple for every five cocks killed. Losses in Illinois have ranged as high as 29 per cent.

To determine the direct loss of birds is almost impossible. Some cripples recover. Others are recovered by different hunters. Too, it's hard to know how many birds take one shot through the body and never quaver—only to die later. If Nebraska's suspected crippling losses are conservatively projected to the total pheasant kill, over 170,000 birds are being lost as cripples. This is plenty of recreation and fine eating gone to waste.

Upland-game-bird losses are not the only ones. Waterfowl crippling losses are comparable. In the 1959-60 Central Flyway shooting season, 206,647 ducks went unretrieved out of a total duck kill of 1,641,339 for a 12.6 per cent crippling loss. Geese tallied up a 12.5 per cent loss in the same season. In the recent years of decreased bag limits, the waterfowler is paying dearly for his unproductive shots.

Under either the upland-game bird or waterfowl heading, every unrecovered cripple is a loss to hunters. And most of this waste can be avoided.

Use of a dog can provide an extension of normal hunting pleasures as well as being a definite asset in cutting bird losses. It is estimated that if the average duck hunter used a good duck dog, waste might be cut in half. It's certain that a retriever which can catch a cripple clinging to submerged vegetation or hiding in heavy rushes or smartweed is performing a feat that no man is liable to duplicate. Certainly more ducks from less shooting would be taken home.

The value of field dogs for upland-bird hunting,

and as a major factor in reducing bird losses, has

been demonstrated in recent studies. In California,

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

upland hunters with dogs reported a crippling loss

of just over 10 per cent, while hunters without dogs

tallied up a 16 per cent loss. Hunters with dogs in

Illinois accounted for lower crippling losses and required fewer gun-hours per kill than hunters without dogs.

upland hunters with dogs reported a crippling loss

of just over 10 per cent, while hunters without dogs

tallied up a 16 per cent loss. Hunters with dogs in

Illinois accounted for lower crippling losses and required fewer gun-hours per kill than hunters without dogs.

Choice of dogs is left to the hunter, of course. Labradors, Chesapeakes, and golden retrievers get the nod from waterfowl enthusiasts. For the ever tricky and run-as-well-as-fly ringneck, the Vizsla, German short-haired pointer, and Brittany are popular all-around dogs for Nebraska-style hunting. The English pointer continues to be the first choice for the dyed-in-the-wool quail hunter.

Regardless of your choice, it might pay to remember that a dog of proved hunting ability is no more expensive to keep than a poor dog. For this reason, selection of a field dog should be made with care and treated as an investment in pleasurable days afield.

For all its advantages, though, the use of a dog alone will not guarantee saving cripples. The dedicated hunter must use other tricks of the trade for worthwhile hunting success.

Holding back on those long, wild shots is where the average hunter can boost his rating. At the beginning of the season there is a good deal of out-of-range shooting. At this stage the neophyte becomes discouraged. Here is where the experienced hunter steps in to take advantage of the uncrowded fields and marshes, and to chalk up significantly higher success.

Understanding the habits of the quarry is another trick to finding crippled birds. The pheasant is notorious for being able to hide in practically non-existent cover as well as for burrowing into heavy cover or animal dens. A methodical, careful search for crippled game often pays off in dividends.

Quick, accurate marking of downed game is another method for success. When a bird drops in heavy cover, keep your eyes on the exact spot as you move in. Better yet, insist that your hunting partners assume responsibility for marking down game. By "homing in" on two lines of sight, the location is more accurately spotted and the search is shortened. If you're alone, hang a hat or handkerchief at the spot where the bird dropped. Then work around the spot in ever increasing circles. Take your time. Kick the cover and keep your eyes open. Often a brief pause is enough to make an old cock bird think he has been spotted. When he moves for new cover, you'll be able to hear or see him and make your move.

In those long milo and cornfields, a cripple often travels straight down the row without the usual crossing pattern. A careful (continued on page 30)

DECEMBER, 1962 7

Nebraska's FRONTIER FORTS

by Greg Smith Each has a story to tell about its part in winning of the WestNOWHERE DOES the buckskin yesterdays rub shoulders with the space age more dramatically than in Nebraska. Here giant missiles pincushion the land, shadowing famed frontier forts of old. And a clear western sky that once was spotted by smoke signals is now crisscrossed by sleek jets roaming the heavens.

The comparison is startling. The difference in time is just a whisper of history, but the difference in warring is ages apart. Just 100 years ago Nebraska was the hotbed of the Indian wars, its 500-mile spread set ablaze by the hostiles. Forts, both military and civilian and large and small, sprung up everywhere. Some still stand. Others are being restored. Still others are remembered only by markers.

NEBRASKAland visitors have the opportunity of

making this unique comparison between old and new

in every part of the state. All of the old posts are

8

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

on the vacation trail and most open for inspection.

Be it Fort Robinson or Atkinson, Kearny or McPherson,

each has its story to tell of the part it

played in winning the West.

on the vacation trail and most open for inspection.

Be it Fort Robinson or Atkinson, Kearny or McPherson,

each has its story to tell of the part it

played in winning the West.

Fort Atkinson is Nebraska's earliest post, the first military establishment west of the Missouri. Now buried under a cornfield, it once held the British at bay. During the 1820's, its guns commanded the Missouri, protecting the newly purchased frontier from the hands of outsiders. Fort Atkinson showed all that America was in the West to stay, and its garrison was ready to take on anyone who cared to think otherwise.

Though the 200-yard square fort was in Nebraska as a peacemaker, its 1,000-man garrison proved its ability to fight when it took on the Aricara Indians on the upper Missouri. The decisive victory assured the growing surge of trappers that they would have safe portage into the wilderness.

Its job of securing America's foothold in the West done, the post was abandoned in 1827. Fort Atkinson deteriorated rapidly and the remains can now be seen only at Historical Society excavations. But it will not long be so. Omaha area residents are working with the Historical Society and the Game Commission to raise funds to develop the site as a state historical park. It's a big order but one that can be done.

Fort Kearny, the most important post on the Oregon Trail, is an example of what restoration can do. Right now the last of the big logs are being put into place on the stockade that once kept the Sioux at bay during the bloody 1860's when the entire state boiled with unrest. Soon other buildings will follow, including a visitor center and duplicates of the original powder magazine and blacksmith-carpenter shop. Three dimensional models of the fort as well as marked trails and sites will aid the visitor in his date with Wild West history.

Kearny, along with Fort Laramie, was the key post during the push West. Past its adobe buildings ground the Conestogas headed for Oregon and California. The Pony Express and Overland Stage beat a path to its door. Later came the telegraph and the iron horse.

During the Sixties when the West was abandoned by the regular army to fight the Civil War, Fort Kearny's volunteer garrison kept the Overland Trail open. The massacre of the Southern Cheyennes at Sand Creek lit the hostile flames that seared the Plains. Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapahoe, and the rest of the great Indian nations joined as one in a blood bath of revenge. Stage stations, ranches, wagon trains, and even Fort Kearny were under attack. In 1864 the situation became so critical that the stockade was thrown up to protect the garrison from the bold hostiles.

Nor was Kearny's duties over with the end of the Civil War. When the Indians saw the bold double line of the Union Pacific pushing its way into the wilderness they fought back with all of the fury of men betrayed. Again the Kearny garrison was called upon to keep the road open, protecting the track-laying crews all the way to Fort Laramie. This massive job done, the post settled back on its laurels, and in 1872 was opened for homesteading, the fort destined to disappear under the sod.

Few realize that there was a second Fort Kearny, older than that built on the Platte. When the government acted to provide protection on the Overland Trail it originally selected a site at present-day Nebraska City. A blockhouse and 60 log quarters were built in 1847-48 for the short-lived post. Soon after the army moved the garrison to the Platte, realizing that the Missouri post would be far removed from the early trail. But the fort has not been forgotten. Nebraska City rebuilt the blockhouse, and it stands today as a proud symbol of the city's touch with the past.

Nebraska's frontier forts followed the Indian wars across the state. Fort McPherson, on the Platte near Maxwell, and Fort Sidney in western Nebraska, were built in 1866 and 1867, respectively. Before these were a series of smaller posts strung out on the Oregon Trail, the most important in western Nebraska, Fort Mitchell. This old-timer, in the present town of Mitchell, is marked but all trace of the buildings that made up its 100 by 180-foot (continued on page 32)

DECEMBER, 1962 9

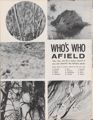

WHO'S WHO AFIELD

You, too, can be a super sleuth if you can identify the telltale marks Match names to pictures. Answers on the next page A. Raccoon E. Deer I. Pheasant B. Grouse F. Porcupine J. Coyote C. Bobcat G. Woodpecker K. Beaver D. Cottontail H. Muskrat L. Squirrel

HUNTER'S BANQUET

KING OF the field and pride of the marksman, the game bird may be a mystery to the inexperienced cook. The pheasant or quail brought home so proudly by the hunter can be a delicacy or a disappointment, depending on the artistry of the lady in the kitchen.

No supermarket label distinguishes the tender from the less tender (text continued on page 16)

DECEMBER, 1962 13 HUNTER'S

BANQUET continued

HUNTER'S

BANQUET continued

Using a sharp knife, cut off wings, feet, and head* Begin at neck and pull skin away from body of bird. Skin, once started, will come off easily. Finish by gutting bird

Immerse bird in boiling water to make plucking easy. Hold bird firmly, removing feathers with sharp pulling motion. Trim around feet and burn off the pin feathers

ROAST PHEASANT: Sprinkle the pheasant inside and out with salt and pepper. Place a slice of onion and 2 or 3 wedges of apple in the body cavity. Tie the legs together and turn the wings under. Cover the breast and legs with 2 or 3 strips of bacon after brushing the outer surface of the pheasant with melted butter. Put in the pan breast side up. Pour 1 cup chicken broth over the bird. Cover loosely with aluminum foil and bake in a preheated 325° F oven. Cook 30 minutes per pound. Baste frequently.

BREASTS OF PHEASANT: Cut the breasts of two pheasants from the bone. Season with 1 teaspoon salt and Va-teaspoon cayenne pepper. Brown well on both sides in Vfe-cup butter with 1 teaspoon chopped onion and V^-teaspoon rosemary. Remove pheasant pieces to a covered pan. Cook until tender in a 325° F oven. Saute four Va -inch-thick servings of ham in the same butter. Place ]/2-pheasant breast on each serving of ham. Saute Vfe-cup fresh or canned mushrooms (halved) in the same skillet for 3 minutes. Push to one side of pan, pour off all but about 2 tablespoons fat. Add 2 tablespoons flour, blend, and add 1 cup chicken broth. Stir until smooth and thick, pour over birds. Garnish with parsley and serve with a tart jelly.

portions or provides a hint as to whether the bird is young or old. The cook is on her own in deciding how to prepare the bird. With a bit of knowledge, however, and much imagination, game provides fare for the most discriminating guest.

The pheasant, built for speed, has firm and sinewy

leg muscles. Unlike inactive domestic fowl, his busy

16

life leaves little time for accumulating fat. Young

birds may be roasted or broiled, but special basting

is necessary to make the dark meat moist and tender.

Older birds should be stewed. Quail has a delicate

flavor, especially the white meat.

life leaves little time for accumulating fat. Young

birds may be roasted or broiled, but special basting

is necessary to make the dark meat moist and tender.

Older birds should be stewed. Quail has a delicate

flavor, especially the white meat.

Hunter and chef may share the credit for delectable birds. Good care in the field is the first step toward tasty meat. Birds should be drawn as quickly as possible and put under refrigeration at the end of the day's hunt to avoid strong or wild flavors. Plucking is best done when the bird is warm.

Once home, handle the birds much like chicken. Any cooking method that adds the necessary fat and moistness is good for pheasant.

THE END

Christmas IN NEBRASKAland

For the Dog Owner . . . □ a doghouse $10.00 □ a dog 25.00 and up □ dummies .50 □ feeding dishes .98 □ long leash 3.98 □ short leash 1.95 □ training collar 1.25 J car kennel 15.00 dog brushes 2.50 OUTDOOR Nebraska plays Santa

Claus. There s a perfect gift

for every outdoor sportsman.

Here's list for any interest

OUTDOOR Nebraska plays Santa

Claus. There s a perfect gift

for every outdoor sportsman.

Here's list for any interest

SAND HILLS NORTHERNS

I was sceptical about our chances and road to river did not help my attitude by Neale CoppleTHERE WAS a time when I scoffed at the idea of catching northern pike in Nebraska. But that was before I gave the Sand Hills a chance and came away convinced. Before I go any further I had better explain. This all started six years ago. The Game Commission had just started their northern pike stocking program. For some reason I just couldn't figure the Sand Hills as good northern water.

A friend told me of fishing there the week before. "Look," I told him, "I'm not the best northern fisherman or the most experienced by a long shot, but northerns in the Sand Hills is more than I can believe."

Before I could go any further he pulled a dog-eared map out of his desk and spread it out.

"Here," he said, "is where you should go."

He showed me the route to Bassett, on to Ainsworth, and south from there to a spot where we would leave the main roads and head out across country on Sand Hills roads.

"You'll want to watch these roads," he said. "They may give you some trouble."

"Oh," I replied, "I don't think they could be bad. It has been dry."

"When you get into the Calamus," he continued, "be careful of spring holes. There are some there. And if you go north for trout, watch out for rattlesnakes."

"Okay," I said, "I'll look out for the spring holes, I'll look out for the rattlers, and I'll probably look like the dickens for northern pike."

It didn't seem like autumn as we headed west and north from Lincoln. A hot wind pushed from the south. A brownish haze on the horizon indicated that the combination of a long dry spell and the wind had whipped dust high into the air.

My wife, Ollie, and I led the way as we drove through Ord that warm afternoon. Behind us were Dale Griffing and his wife, Emily. As our cars roller-coasted along the dipping road I mused to myself about how few persons were aware of the fascinating Sand Hills. The unique terrain, which extends from north-central to northwest Nebraska, is made up of huge sand dunes, covered for the most part by prairie grasses.

A combination of a normally high water table as well as a clay base in valleys between hills has been responsible for many Sand Hills lakes. These provide some of the finest fishing in Nebraska. Depending upon their depth, they produce perch, crappie, bluegill, bass, and, I hoped, northern pike.

The water attracts waterfowl by the thousands. Few sections of the country have as many prairie chickens. There are also pheasants, and in recent years the Sand Hills have produced excellent deer hunting. Small wonder, I mused, as I drove along the road toward Bassett, that a sportsman's pulse quickens when he enters the Sand Hills.

After spending the night in Bassett, Griff and I got out our maps and traced our route. A red line led from Bassett to Ainsworth, obviously a good paved road. A dotted blue line led south from Ainsworth, an improved road. Then green lines branched out into the hills.

"What kind of roads are those green ones?" I asked.

"Those are Sand Hills roads," said Griff with a chuckle.

"Well," I continued, "if there are roads, we'll get there. It has been so dry any roads ought to be okay."

Griff chuckled again.

I didn't understand that chuckling until perhaps 20 minutes after we had turned off the improved road leading south of Ainsworth. It was there our "green" road turned sharply southwest. Ahead of us, winding up, over, and around the hills was our road—a road crisscrossed with drifts of sand. Even as I slowed the car and watched I could see the sand shifting before the high winds.

I stopped the car and waited for Griff to catch up.

"This is the road?" I asked.

"This is it," he said with a broad smile, "and actually this isn't too bad."

"Griff," I said, "whether we catch northerns or not I have learned something. Those red lines on the map mean good roads. Those dotted blue lines mean pretty good roads, and those green lines—those green lines, Buddy, mean no darned roads at all."

We followed those drifting roads southward toward the headwaters of the Calamus River. We rounded fences, went through gates, and stopped to ask ranchers the way. They directed us courteously and added, "But please be careful of fire. It is awful dry." The ranchers had experienced weeks of drying winds. They were sitting in the midst of a prairie tinder box and they knew it.

Finally we dropped in a valley and there was the Calamus—scarcely more than a creek at this point. Here and there the ribbon of water wound into a mass of brush where it virtually melted into a swamp. It didn't look like (continued on page 30)

DECEMBER, 1962 21

WHAT TO DO WITH THE SKIN...YOUR DEER COMES IN

WOULD YOU throw away a $20 bill? Of course not, yet every year many hunters do just that when they discard their deer hides. A man's buckskin jacket, which takes three to four hides, will cost the sportsman between $20 and $30. The same jacket from a specialty or men's store is priced from $50 up. Four to eight pairs of gloves can be made from one deer hide at a cost of about $2 each. Those in a specialty store are more.

Not only do hunters save money by having clothing and other items made from their deerskins, but they also have the satisfaction of knowing the jacket, gloves, or shirt they are wearing came from a deer they brought down themselves. At the same time, deerskin will outlast most other materials, is luxuriously soft, attractive, and ideal for winter wear where warmth is important.

The pioneers used deer, antelope, and buffalo skins for clothing. Buckskin was easy to get, durable, and practical for the frontiersman whose home was often the clothing he wore on his back. Today buckskin has moved into the luxury field. Modern tanning methods have much to do with this new-found popularity. In addition to the traditional browns and tans, buckskin now comes in a variety of colors.

The list of items made from deerhides is almost endless. It includes jackets, coats, hunting pants, gloves, shooting mittens, hats, moccasins, purses, wallets, dresses, and shirts.

There is more to a deerskin jacket than shipping a hide to one of these manufacturers, however. Actually, a good hide starts even before you draw a bead on that handsome buck. Flaws and scratches in the hide from barbwire fences and snags can make a perfect-looking hide worthless.

The skin should be fleshed as soon as possible after the deer has been skinned. Use a good skinning knife to do the job. The wrong knife can result in cuts on the hide that will likely make that part of it unusable. Once fleshed, salt the hide, using five pounds of ordinary table salt on the average hide. Rub the salt in thoroughly and allow it to stand for two days. Repeat and the hide's ready to be tanned.

It is often a good idea to take the hide to a taxidermist to be tanned. He won't actually tan it himself, but since he sends hides to tanneries in lots of 50 or more, the cost will be less than a single hide. The skin can be dyed any color desired with a slight additional charge for exotic colors. From there, it's ready to be made into a variety of items, garments, and gear that any sportsman will be mighty proud to own.

THE END DECEMBER, 1962 23

FOR THE DUCKS

by Bob Morris Buy a migratory bird stamp and cast your vote for the nation s waterfowl futureTHE VIGIL began early this fall when the first few flights of ducks began moving down from the north. Every sportsman's eyes were to the sky, wondering how many birds there would be for the season. Some hunters didn't even uncase their guns, preferring to let the ducks go by in the hope that in some way, they could help in bringing back the duck population. And if they did shoot for the small limit, they aimed for the drakes, giving the birds every chance possible to recover for future hunting seasons.

But sportsmen can do more than aiming for drakes or not shooting at all. Their biggest assist comes when each one plunks down $3 for a duck stamp. Though the season is over, it's still the thing to do, the money earmarked for the purchase of desperately needed breeding and nesting grounds. The purchase of a duck stamp is the best way each sportsman can contribute to the future of duck hunting.

In order to survive, waterfowl need nesting areas, places where adequate water is available for them to reproduce. Without adequate reproduction, a high percentage of the birds shot every year are adults. In surveys conducted for the past three years, Game Commission technicians have determined that more than half the ducks shot in that period have been adults compared to the normal ratio of nearly three young birds to each adult.

Through the sale of duck stamps since their inception in 1934, the Fish and Wildlife Service has acquired over 250,000 acres of suitable waterfowl habitat. But on the other hand, nearly twice that acreage has been lost to drainage. The prairie pothole region in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa, and Montana once included 115,000 square miles of waterfowl breeding habitat. Today, that region has dwindled to less than 56,000 square miles. These losses have done irreparable harm to waterfowl and other wildlife.

Since the inception of duck stamps in 1934, waterfowl hunters in the United States have contributed more than $75 million toward the purchase of waterfowl habitat through the purchase of over 36 million stamps. These funds have provided much suitable land, but more is needed.

Formally called the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp, it's popularly known as the duck stamp. Every hunter 16 years of age or older must purchase a stamp before he can hunt waterfowl.

The Stamp Act came about because sportsmen

and conservationists became alarmed by the rapid

decline in the numbers of waterfowl during the

drought-plagued Thirties. Adding to the problem

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

was government subsidized drainage which destroyed millions of acres of marsh and water areas

formerly used by waterfowl for nesting, resting,

and wintering places. Much of the land drained

proved to be practically useless for farming.

was government subsidized drainage which destroyed millions of acres of marsh and water areas

formerly used by waterfowl for nesting, resting,

and wintering places. Much of the land drained

proved to be practically useless for farming.

A series of legislative steps have been taken to protect waterfowl. In 1916, the United States signed the first of two agreements with Canada for the preservation of waterfowl. In 1936, the Migratory Bird Treaty was extended in include Mexico. A program authorizing the acquisition of land and water areas for waterfowl went into affect in 1929. But funds to buy this land were badly needed. The Stamp Act of 1934 supplemented and supported the original act.

The late J. N. "Ding" Darling, famous cartoonist and noted conservationist, was the first chief of the U. S. Biological Service, the forerunner of the Fish and Wildlife Service. In later years he told of the amusing circumstances surrounding the design of the first duck stamp. In the bureau's zeal in having the Stamp Act passed, it had neglected to design a stamp. After the law was passed, a call came from the government engraving department asking that the design be sent to them immediately.

Darling, unable to find an artist, worked all night and the next morning to complete three sketches, then sat around on pins and needles awaiting the verdict. After two days he could stand the suspense no longer and called the engraving department. He was told one of his designs had been accepted and was in the process of being printed. He had to wait until the stamps went on sale to find out which of his designs had been used. Darling's first design is now a collector's item.

After the frantic method of selecting the first stamp, outstanding artists were invited to submit entries and selection of the stamp was made from this limited group. In 1949, these limitations were lifted and all wildlife artists were given the chance to compete.

C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, Game Commission artist, has entered his excellent drawings for a number of years and in 1952 and 1956 was runner-up in the national contest. The winning artist receives no monetary prize for his entry but has the satisfaction of knowing he won over the top wildlife artists in the country.

Two artists have had their entries chosen more than once. Maynard Reece, former staff artist of the Iowa Department of History and Archives, won in 1948, 1951, and 1959. Walter A. Weber of Vienna, Virginia, submitted the winning design in both 1944 and 1950.

For the first 15 years, the duck stamp cost $1. Beginning in 1949, the price was raised to $2, and in 1959, was upped to $3. In 1934, 635,000 were purchased. The number increased each year until 1938 when the sale went over the million mark for the first time. In 1946, two-million stamps were sold and remained at that figure until 1959 when only 1,630,311 were purchased.

In Nebraska, the number of duck stamps sold has decreased slightly over 50 per cent in the past five years, from 67,414 in 1957 to 33,380 in 1961. At the same time, the number of sportsmen hunting waterfowl has dropped about the same. Shorter seasons and lower bag limits have been contributing factors, of course, but what many hunters fail to realize is that the less money available through the sale of duck stamps, the less ducks there will be. This has developed into an almost losing battle, with the Fish and Wildlife Service receiving complaints from hunters about restrictive seasons while these same persons refuse to do anything to help alleviate the situation.

Even stamp collectors who don't know a mallard from a prairie grouse get into the purchase of duck stamps. A recent survey shows that if you had purchased a duck stamp every year from 1934 to 1958 the 24 stamps would have cost $35. They are worth, unused and in tip-top condition, over $110.

Whether you are collecting stamps or want to continue to be able to get out in a blind on a wind-swept day with ducks coming into your decoys, it's important that you buy a duck stamp. Canvasbacks and redheads are already on the protected list. Let's hope this isn't an indication of the future.

THE END DECEMBER, 1962 25

BIG GAME CAMP

continuted from page 5them at one end, and spread into a scissor. Peg down the corners of the tent within the crib, tie its peak to the shear, and spread the legs into position. A tent crib holds a tent securely and neatly, and it eliminates all wide-spread stakes and guy ropes, leaving nothing to stumble over and cause a fatal hunting accident.

Locate the fire pit at least eight feet in front of the tent. It will then serve both for cooking and heating. Dig a narrow trench, drive a green, forked stick at each end, and use green hook-branches to suspend the kettles from the crane.

Cut a plentiful supply of firewood, and stack it close to the fire pit. You'll use a lot of wood over a period of days, and it's best to gather it beforehand so you'll lose no time from hunting. Bury two crotched logs, with the forks 18 inches above the ground, for a sawhorse. You can then cradle long pieces of heavy wood, and slice off fire-length chucks in a hurry. Another section of heavy, forked log, lying directly on the ground, holds wood billets while splitting them with the ax.

You'll want a table of some kind to prepare your meals, and to sit up to when it's time to eat. Bury four strong forked sticks at the corners of a 24 by 36-inch rectangle, so the forks are somewhat below waist level. Lay two straight sticks into the forks to support the table top. Use some straight sticks to brace the table, fastening them with square and diagonal lashings. For the table top, use straight sticks. Lash them down if you wish, although if they are heavy, they will lay in well of their own weight.

Three more 14-foot poles make the meat rack.

Lay the poles on the ground, side by side, and make

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

a shear lashing around them for a tripod. With this

rig, one can hoist a heavy animal into a hanging

position by pushing one leg up, then another, until

the carcass is off the ground. Once off the ground,

the deer will cool properly.

a shear lashing around them for a tripod. With this

rig, one can hoist a heavy animal into a hanging

position by pushing one leg up, then another, until

the carcass is off the ground. Once off the ground,

the deer will cool properly.

Finally, establish a latrine 40 to 50 yards from your camp area, and a refuse and trash pit at a somewhat closer distance. A woodsman's rule of thumb as to the size of these two facilities is to "dig them wide, and dig them deep. Both are completely filled with earth and leveled off when your camping's done. For that matter, whenever a camp site is abandoned, only "grubbies" are so inconsiderate as to leave any type of refuse lying about to mar the outings of others.

You have completed a basic camp. Sure, it's taken you a full half day, but there's comfort and utility here. The added atmosphere and build-up of anticipation will make your hunt twice as enjoyable. And who knows? When you touch off your first campfire, the spirit of Davey Crockett might just drift in through the dark to say hello.

THE END

SHELL LAKE

Variety of game, hot fishing yours in Sand Hills hideawayAS THE SUN comes up over the rolling Sand Hills, heralding the start of another day, a ^^^hen mallard leads her brood out of the protective cover of the rushes. A mule deer and her fawn cautiously approach the water's edge for a drink. In the water, a bass moves in on an unsuspecting minnow. And out in the hills, prairie grouse begin another day in their ages-old hideaway.

This is Shell Lake Special Use Area. In the extreme northeast corner of Cherry County, 15 miles northeast of Gordon, Shell Lake is one of 40 such special use areas. They range in size from less than 100 acres to Lake McConaughy's whopping 37,000 acres. By classification, these are primarily for hunting, fishing, and other wildlife values with other recreational uses secondary.

Shell Lake's main attractions are its 80-acre lake and healthy game population. There are no crowds here, even on week ends. Yet, in this lonely splendor lies the real beauty of Shell Lake.

Anglers have ample opportunity to fish every spot on the lake without interruption. You can fish from the shore, or using one of the two boat-launching ramps, take a boat out for a pleasant day. Bass, northern pike, perch, and rock bass provide top sport.

Fishing is not just a summer-time affair. When the lake freezes over, ice anglers get in some great perch action. Northerns and bass are also brought to bay.

Spring begins with the arrival of ducks—mallards,

pintails, teal, redheads, and canvasbacks. As they go

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

through their courtship rituals, the elms and willows

break out with their foliage and the land comes alive

again for another season's growth. Part of Nebraska's finest waterfowl breeding grounds, Shell

Lake contributes an important share of the ducks

that come from the Sand Hills.

through their courtship rituals, the elms and willows

break out with their foliage and the land comes alive

again for another season's growth. Part of Nebraska's finest waterfowl breeding grounds, Shell

Lake contributes an important share of the ducks

that come from the Sand Hills.

Out in the hills, grouse move to their favorite booming grounds as the warmer weather arrives. There the cocks strut and twist, then stamp their feet in a rapid tatoo. Their tails spread in an upright fan and wings droop. Then comes the booming sound for which they are so famous. Come fall, their offspring will be part of the bag taken from the area.

Shell Lake consists of 640 acres of rolling Sand Hills with the lake in the southeast quarter. A well-marked gravel road leads you right into the picnic area where tables, fireplaces, and well water are available. Hunters take advantage of the opportunities offered at the state area, working the hills and valleys for grouse or setting out a spread of decoys to lure in a passing flight of ducks. Deer hunters also find Shell Lake productive.

Shell Lake has much to offer those seeking hunting and fishing away from the crowd. And for the nature lover, the area provides the chance to observe wildlife in its natural habitat.

THE END

GET THAT BIRD

(continued from page 7)approach to the field's end often produces the sought-after bird.

If you're sure you've hit a bird, but it doesn't fold or flinch, keep your eyes on it. In many cases a fatally hit pheasant or duck will set its wings and slant down on a long glide. Just before landing, the bird may fold up and drop like a stone. Mark the spot and the reward is often a bird which almost made the disappointment category.

Finally, and most elementary, don't blast indiscriminately into a covey rise or settling flock. Pick your target and follow it through. You'll be much more assured of connecting, as well as not having several hard-to-find cripples dropping into cover.

Keeping these suggestions in mind, the amateur as well as the experienced hunter will have a better chance to come home proudly from a successful hunt with a game bag full of birds. And he'll take satisfaction in knowing that his birds are not doomed to the category of which few are proud, hit but not retrieved.

THE ENDSAND HILLS NORTHERNS

(continued from page 21)northern water, this undersized Sand Hills river. We assembled our spinning equipment and worked upstream. The shallow water was running crystal clear. Here and there it wound into a bank, cutting a deeper hole. We saw a cut in a high bank where the water seemed to grow darker. Staying well away from the hole, we cast. The quarter-ounce spinner scarcely had settled when it was struck. A small northern, perhaps 15 or 16 inches, turned its side to us. "It's a northern," I shouted.

But I had been doing too much talking and too little fishing. The little pike headed into a bank where a tangle of roots hung and shook loose. After a few actionless casts we climbed the bank and looked down into a hole that must have been eight-feet deep. There they were, a half-dozen northern pike. Their long snouts pointed upstream. Their dark bodies fanned out below the ripples.

Downstream, at the edge of a small swamp, the stream entered a channel of perhaps 20 yards. Then it dropped into a deep hole. I cast the spinner into the hole. It skirted the bank, under which I thought a fish might be waiting. Then came the strike. The reel brake gave line as the fish headed downstream. It gave line again when the fish went back to the head of the hole. For perhaps five minutes we did not see the fish that was doing these drastic things to the spinning rod and reel.

Then a big side showed for just an instant. But that glimpse made my work more earnestly. Twice the pike seemed to give up. Twice Griff was left holding the net while the line shot upstream again. Finally, Griff "scooped and headed shoreward, carrying a 6y2-pound northern.

Gleefully we took the fish the short distance back to the car. As our wives admired the catch, I turned toward the hills and almost shouted, "Golly, you are right. There are northerns in the Sand Hills." Since that initial trip I have returned many times, returned as a believer that the Sand Hills offers the tops in northern pike fishing.

THE END GOOD WORK should not go unrecognized and for that reason Nebraska owes a bouquet to the writers, artists, and publishers of OUTDOOR Nebraska. This constantly improving state periodical has attained a ranking among the better publications of the nation dedicated to the advancement of a state. If OUTDOOR Nebraska must yield ground to such excellent state publications as Arizona Highways it is not from inferiority of content and interest, but in its modest budget, which forbids sufficient scenes in color. Arizona has its reds and yellows and browns. Nebraska has that plus the blues, greens, and silvers. The Nebraska story cannot be fully told in blacks and whites. It takes all the hues of the rainbow. There is a challenge to Nebraska. It is to live up to its fine state publication, to put into the budget something proportionate to that which the editors and publishers are putting out in the product. No money will be misspent which places all the winning tools into the hands of OUTDOOR Nebraska. THE END The Lincoln Star 30 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

Dreams Not So SweetPENNSYLVANIA . . . Reality turned out to be pleasanter than dreams for one Pennsylvania deer hunter—if he had only been awake to take advantage of it. The hunter got a bright and early start the opening day, but soon fell fast asleep. He awoke with a start to find a magnificent buck looking at him. By the time the hunter got into shooting position, it was too late and all he got was a snapshot as the deer went loping into the forest.

MISSOURI . . . When an unusually honest fisherman brought home a bass weighing 6 pounds, 1 ounce, word got around. A conservation agent, keeping in mind the Missouri record of 5 pounds, 14 ounces for this species, looked him up and asked about the lunker.

"I have to be honest," replied the angler, "I didn't catch it. It chased a bluegill right out on the bank at my feet and all I had to do was pick it up."

Bombed BlackbirdsPENNSYLVANIA . . . Part of a flock of Pennsylvania blackbirds literally got bombed out of the air by a hailstorm early this summer. About 30 of the birds were flying across a field when a terrific storm came up. About half the birds fell, apparently knocked down by the large hailstones. Once they recovered their senses, the birds flew away, probably wondering what hit them.

Phone Nets AnglerMISSOURI ... A local fisherman wrote a Missouri conservation agent about the amount of "telephoning" going on in the Mississippi River. Telephoning refers to the use of telephone magnetos to illegally stun fish electrically.

The agent joined forces with other officers to investigate the report. The joint operation failed to find any "telephones" but did meet the man who wrote the complaining letter, however He was fishing in the river—without a fishing permit.

Up a TreePENNSYLVANIA ... A hungry cat has decided to leave pheasants alone after losing two rounds to a hen and her brood. Each time the feline made her play on the nest, the hen chased her up a tree. For all observers know, the cat's still up there, hungry but much wiser.

Hot PonyIDAHO ... A cow pony started a stampede recently in Camas County when a spark from his metal horseshoes started a 500-acre grass fire. According to the National Wildlife Federation, it took some 30 fire fighters, 4 bulldozers, 2 tankers, 2 Bureau of Land Management airplanes carrying borate slurry, and a helicopter to bring the blaze under control. The story must be true. The cowboy who owns the horse doesn't smoke or carry matches.

Well-Traveled TunaHAWAII ... A 26-pound skipjack tuna captured off Oahu has quite a bit of mileage under his belt. Tagged in the fishing grounds of the American coast, it is estimated that the tuna traveled at least 2,500 miles of ocean. His capture has provided the first evidence of the movement of skipjacks from American fishing grounds into Hawaiian waters.

The Robin That Isn'tPENNSYLVANIA ... A Pennsylvania robin is fast becoming the most frustrated bird in the country, all because of a phantom redbreast he can't get rid of. The robin's troubles started when he spotted his reflection in the cellar window of a vacant house and decided the interloper would have to go. Since then he daily takes flying rushes at his image, knocking himself silly each time.

FRONTIER FORTS

(continued jrovn page 9)stockade are gone. Built in 1864, the fort's garrison had many a showdown with the hostiles, the Indians brazenly chasing stagecoaches to its very gates.

Fort McPherson was Buffalo Bill Cody's bailiwick when he was chief of scouts for the famed Fifth Cavalry. The post's garrison also patrolled the trail, but in later years campaigned throughout southwest Nebraska and Kansas. Such famous officers as Crook, Sheridan, and Custer graced its quarters. McPherson played a vital role in winning the West from the time it was commissioned to its abandonment in 1880. Today the fort is a national cemetery with many of the Indian fighters of old interred there.

In its early years Fort Sidney was still another link in the army's chain of posts along the trail. It came into its own when the Indian wars moved north with the discovery of gold in the Black Hills. Adjacent to the railroad, it became an important supply post to outfits trying to keep both gold hunters out and the Indians pacified, a job that proved impossible to fulfill. The post was active until 1894 when it was abandoned and the buildings sold at auction. Some still stand today, and the town of Sidney, in co-operation with the Historical Society, is attempting to procure them.

No fort, in Nebraska or any other state, played a more key role in defeating the Indians than Fort Robinson. Here the Indian wars began and ended. Here Crazy Horse was murdered and Dull Knife's fleeing Cheyennes made their dramatic last bid for freedom. Here the Sioux returned with the scalp of Custer, here Red Cloud tried to keep the peace he had pledged for the thousands of hostiles confined at his agency nearby.

Robinson is now a state historical park and many of the old buildings such as the adobe officer's quarters built in 1876 are still used. Established in 1874 at the height of the Indian wars, it became the key post in the West in the last campaign to subdue the Indians. From here the final bloody wars were launched, the last coming at the Battle of Wounded Knee where Big Foot's ghost dancers were slaughtered almost to the last man, woman, and child. Robinson continued as an active military post until 1948.

Camp Sheridan, just 50 miles to the northeast near Chadron, was another fort spawned by the Indian wars. Here the garrison saw to it that Spotted Tail's Brule Sioux would stay on their reservation. All trace of the camp is now gone.

After the Sioux were moved to their permanent reservations in South Dakota another military post was built near present-day Valentine to keep them in line. Fort Niobrara, now a national wildlife refuge, has a museum displaying the old relics of the post, and nearby, where cavalry once charged, buffalo, elk, and longhorns roam. Built in 1880, the post was active until 1906.

Fort Hartstuff near present-day Ord played a key role in protecting early Nebraska pioneers. Built in 1874 when the Sioux were riding rough-shod over the plains, it still stands today, a stark reminder of the days when the Nebraska scene was not quite so peaceful. Hartsuff has also been classified as a state historical park and plans call for early renovation.

Fort Crook and Fort Omaha, both at Omaha, had long and colorful careers during the Indian uprising. Fort Omaha was the headquarters of the army during the construction of the Union Pacific. Built in 1863, it was in use until 1947 and many of the old buildings remain. Fort Crook, built in 1891, was active until 1948 and is now a part of the Strategic Air Command's giant defense complex.

There are dozens of other forts in Nebraska, many of them thrown up by settlers during the height of the Indian wars. Representative among these are Fort Nendel in Sheridan County, Fort St. James in Cedar County, Fort Montrose in Sioux County, Fort Heath in Lincoln County, Fort Independence at Grand Island, Fort Butler in Thayer County, and Fort Desolation on the Loup near Fort Hartsuff.

Nebraska is mighty lucky to have so many of the old posts still standing. Restoration work now being done and that planned in the future promise that this important part of the state's Wild West heritage will ever be retained.

THE END 32 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

SPEAK UP

Send your questions to "Speak Up", OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, State Capitol, Lincoln 9, Nebr. Cook Out Craft"We enjoy OUTDOOR Nebraska and hope to visit all the interesting places mentioned in the magazine. Our hobby is fishing and camping, and we take along a unique little camp stove I made out of a bucket.

"An elbow and stove pipe draw the smoke out. There is a small opening in front for draft. By placing a steel plate on top over the grate we can cook our entire meal on it. When the coffee and vegetables are done, I put the steel plate on a sandy spot to keep the food warm while I grill the steaks or other meat.

"By the time we are through eating the fire is out and the stove cold. We leave no coals behind, and our camping spot is as clean as when we arrived."—William W. Franklin, Fremont.

Question of Color"What happened to the color of that bullfrog on your July cover? Do your frogs all look light-colored like that or is this just an oddity?"—A. J. Holdren, Amarillo, Texas.

Bullfrogs vary in basic color with those in the northern climates showing a tendency toward a more variable intensity of green. In the south they are mostly dark green with some individuals appearing almost black. In Nebraska, they run the gamut of color variations. Some are lighter than the one on the July cover although the majority are darker. —Editor.

"Since reading the article in OUTDOOR Nebraska on how to prepare carp we no longer give them away, and, in fact, even fish for them now. I prepare them in the pressure cooker and vary the flavor with smoke salt, savor salt, etc., and they are delicious. Now, we never buy salmon.

"Scoring and frying carp in deep fat melts the small bones. One must is cutting out the dark strips. They cause a strong taste.

"We enjoy the magazine very much."—Mrs. Maurice White, Plainview.

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 DOGS FOR SALE: Vizslas, Hungarian pointer retrievers. Short hair, short tail, golden-rust color. Limited number of quality stock. Maggie z Selle, Line. Route 3, Seward, Nebraska. Phone 8647. AKC BLACK LABRADOR. Pups. Started dogs. Outstanding pedigrees. April males by field trial champion. Top field and show breeding. Kewanee Retrievers, Valentine, Nebraska. Phone 26W3. SMOKE GAME FISH: Build Electric Smoker, cost under $5.00. Anyone can build in two hours. Full instructions and recipes $1.00. Oldtimer Lure Company, Kootehai, Idaho. SNAGGER FISHERMEN: Get down to the bottom. Get the big ones. Try the new Skitter Snagger Weights. Ten sizes, from \'2 ounce to 3,4 pound. See your dealer. "FREE". Introductory Offer. 5 hand-tied flies. Send 25£ for postage and handling to Cabela Distributing, Box 672, Chappell, Nebraska. FISH VIEWER: See under water. Great for ice fishermen. 4 feet long, 2 inches in diameter. $4.95 post paid. Bover's Shopping Service, Box 115, Strasburg, Ohio. OCTOBER WHELPED Brittany Spaniel pups ready now for Christmas present for the family and a hunting dog ready for you next fall, Dad. Rudy Brunkhorst, Columbus, Nebraska. AKC FLAT-COATED RETRIEVERS. Puppies for field trials and hunting. Dam proven in trials. Sire English import. Mrs. Richard Lende, 765 Olive Street, Denver 20, Colorado. FOR SALE: Hungarian Vizsla. Excellent pointer-retriever companion hunters. Import bloodlines. From one of the finest Vizsla kennels in the country. Write Warren Goldstein, Rural Route No. 1, No. 4, The Knolls, Lincoln, Nebraska. GUNS NEW, USED, AND ANTIQUE GUNS: Weatherby, Browning, Winchester, Ithaca, Colt, Ruger, and many others in stock. Sell or trade. Write us or stop in. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, Just off U.S. 136, Fairbury, Nebraska. CUSTOM GUN-STOCK WORK. Rifle, shotgun, and pistol grips. Bill Edward, 2333 South 61st, Lincoln. Phone 489-3425. FOR SALE: Original SNABB Swedish Ice Augers. Takes the work out of ice fishing, cuts through 36 inches of ice in 25 seconds. Dealer inquiries solicited. Retail price $14.95 post paid. Myers Supply Company, 414-16 North Sycamore Street, Grand Island, Nebraska. CUSTOM HATCHING of Rainbow, Kamloop, and Kokanee fingerling trout for farm pond stocking. Ralph Wagoner, Dugout Creek Hatchery, Broadwater, Nebraska. MISCELLANEOUS KEEP WARM: Send 10 cents for handbook catalog of down clothing and lightweight camping equipment. Gerry, Department 238, Boulder, Colorado. EXPERT TAXIDERMY: Game heads, birds, and fish. Satisfaction guaranteed. 16 years experience. John Reigert, Jr., 924 South 39th Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. Phone 489-3042. PONTOON BOAT KITS: Build your own and save hundreds of dollars. Pontoons 14 feet to 30 feet. Components, hardware. Send for price list. Phil's Mail Order, Department M-l, P.O. Box 92, Hope, Arkansas5,000 Firearm Bargains

Are you a gun trader? Gun collector? Or are you just plain interested in guns? If you are, you'll profit from reading the bargain-filled columns of SHOTGUN NEWS, now published twice each month. It's the leading publication for the sale, purchase, and trade of firearms and accessories of all types. SHOTGUN NEWS has aided thousands of gun enthusiasts locate firearms, both modern and antique—rifles, shotguns, pistols, revolvers, scopes, mounts ... all at money-saving prices. The money you save on the purchase of any one of the more than 5,000 listings twice a month more than pays your subscription cost. You can't afford to be without this unique publication. Free Trial Offer! Money Back Guarantee As a special introductory offer, we'll send you the next issue of SHOTGUN NEWS free of charge with your one-year subscription. That means you get 25 big issues. What's more, if you're not completely satisfied, just tell us. We'll immediately refund your money in full and you can keep the issues you already have. Fair enough? You bet! Fill in the coupon below and mail it TODAY! THE SHOTGUN NEWS Dept. ON Columbus, Nebraska Yes, send me the next issue of SHOTGUN NEWS FREE and start my subscription for one year, $3 enclosed—to be refunded if I'm not completely satisfied. Name Address City and State

notes on Nebraska fauna...

GADWALL

THE GAD WALL, Chauleasmus slreperus, is perhaps one of the least-noticed ducks. Unlike most of the clan, the male's plumage is very conservative in color, causing many hunters to mistake him for a female pintail, baldpate, or mallard.

There are at least a dozen local names for the gadwall. They include gray duck, chickacock, creek duck, prairie mallard, redwing, specklebelly, and widgeon.

An adult male in winter plumage appears as a

slender grayish-brown-bodied duck with a paler neck

and head. The characteristic black rump is a key

identification feature while the bird is sitting on the

water. His bill is usually bluish-gray with a trace

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of orange at the base and along the edge. His mate's

is dull orange with dusky spots. The male's feet are

usually brighter, being yellow to yellow-orange with

dark webs.

of orange at the base and along the edge. His mate's

is dull orange with dusky spots. The male's feet are

usually brighter, being yellow to yellow-orange with

dark webs.

A uniformly brown-mottled body with a paler neck and head are identifying colors of the female. Except for the yellow-orange bill and feet, she looks very much like a smaller version of the hen mallard or pintail. In flight, both sexes show white breasts and bellies. The gadwall is the only river or pond duck which has white in the speculum. This is readily seen on the rear of the wing while the bird is in flight, though it is somewhat obscure on the female. The middle coverts of the male are chestnut colored, looking like a reddish wing patch.

The female's call is limited to quacking, but her mate may quack or produce a whistled call or combinations of both. The call of neither, however, is as loud as that of the mallard.

Gadwalls usually fly in small, compact flocks. This duck is a swift flyer and usually flies in a direct course without the dipping and soaring characteristics of some other species with which he may become confused. He is frequently found in association with pintails and baldpates. Immature baldpates closely resemble the gadwall, however the baldpate's white wing patch is on the fore part of the wing rather than the rear. He sits low and flat on the water, while the baldpate rides buoyantly with tail held high.

Distribution is almost world-wide. Australia and South America are the only two places where the duck is not found. The main breeding range in North America extends westward from the Nebraska panhandle to the West Coast and northward from the panhandle to central Manitoba in Canada. Distribution throughout the range is somewhat irregular in that the gadwall may be plentiful in some areas and absent in others. The reason for reported scarcity in some areas may be due to his being confused with the baldpate and pintail.

The northern limits of the wintering range extend from the Maryland coast southwestward to west-central Texas and northwest to the Oregon coast. The southern limits extend into the states of Veracruz and Jalisco in Mexico. This area includes the eastern seaboard states, the Gulf Coast states, and the West Coast, including Baja California in Mexico.

A late spring migrant, the gadwall usually doesn't appear until the ponds and marshes are free of ice. Although the migration flight is relatively short, southward movements begin in late August and early September. Being primarily a fresh-water duck, he is found far inland from the coast in winter ranges on ponds, sloughs, marshes, and lakes.

Vegetable matter is the primary staple. Pondweeds, algae, widgeon grass, musk grass, and bulrush are important plants. Both vegetative parts and the seeds are utilized. Snails and various insects make up only about two per cent of the total diet. As might be expected, the greatest intake of animal matter is during the spring and summer months. Although the gadwall is essentially a surface-feeding duck, he can and often does dive for his food when necessary.

Islands are preferred nesting sites. If unavailable, the hen will build her nest in a meadow or grassy prairie. The nest is always on dry ground and almost never near water. It is a scooped out hollow, usually hidden beneath bushes or in dense grass. Grasses mixed with down from the hen's breast serves as lining. After mating, 7 to 13 dull creamy-white eggs are deposited. Each is slightly more than 2 inches long. Incubation is from 24 to 26 days. The young can swim as soon as they leave the egg.

The gadwall is a good eating bird and worth special attention from the hunter.

THE END DECEMBER, 1962 35