OUTDOOR Nebraska

August 1962 25 cents

OUTDOOR Nebraska

August 1962 Vol. 40, No. 8 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. GREG SMITH, managing editor; Jane Sprague, Wayne Tiller, C. G. "Bud" Pritchard

FLOATING the Calamus

Leisurely canoe trip, we thought. But that was before we put inPLUNGING THROUGH the swirling river, I could hear the canoe groan as the watery fury hit it from all sides. Whirlpools grabbed at the light craft. From the back seat I saw the bow plunge squarely into a twisting black cone. The canoe shuddered, then the nose was out and my end felt the full force of the water. Here, where the river dropped several feet in a short distance, the usually peaceful Calamus turned into a rampaging torrent.

"Keep paddling to the right," I yelled at Wayne Tiller in the bow. Stopping now would mean a dunking.

Shooting safely across the whirling surface, the snarl of sharp limbs reached out to grab us. Wayne and I paddled harder, but the current pushed us toward the tangle. Our paddles bit again and again into the boiling water in a vain attempt to alter our course. I braced for the collision, but it never came. At the last moment the unpredictable current caught the bow and swung it downstream right under the outermost branches. Wayne and I ducked and were again in calm water.

We were floating the Calamus River about 25 miles northwest of Burwell but didn't expect to find any fast water like this. Only a year before my son, Kent, and Gerald Chaffin and I floated 34 easygoing miles of the upper Calamus without any trouble.

I was anxious to explore the lower regions of the

Sand Hills river. It was early July before Howard

Weigers and Wayne Tiller of Lincoln and Karl

Menzel and Gerald Chaffin of Bassett finally got

AUGUST, 1962

3

together for the weekend outing. We met late

Thursday and drove 30 miles northwest to the first

night's campsite on the Calamus.

together for the weekend outing. We met late

Thursday and drove 30 miles northwest to the first

night's campsite on the Calamus.

Once the camp was set up, Wayne and Karl turned out with fishing gear to test four nearby gravel-pit ponds. Howard and I stayed at camp to get supper. Gerald would be in later since, as he said, he had "let his work interfere with his fishing."

About the time Gerald got there, Wayne and Karl returned with a nice mess of bass in the iy2-pound class. It didn't take much to convince Howard and me that the fish would make a lot better meal than we were putting together.

As we sat down to eat, the bullfrogs began their

nightly song. Karl and Wayne figured that frog legs

would be just the ticket for the next night's meal.

Once they'd eaten, they pushed off in Howard's

canvas canoe and started working the banks of the

pond. Within 30 minutes, the two of them had hand

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

grabbed at least a dozen croakers. Once they returned, the crew turned in to be in good shape for

the big trip in the morning.

grabbed at least a dozen croakers. Once they returned, the crew turned in to be in good shape for

the big trip in the morning.

The sun was still perched on the horizon the next morning when Karl, Wayne, and Gerald made their first casts into the pond's calm, ripple-free surface. Before Howard and I could crawl out of our mountain tents, the anglers were back in camp displaying their catch of bass and a few more bullfrogs.

But this was the day of the big trip, so we had to move fast. A quick breakfast and a planning session got things into high gear for the morning. We spotted a car about 9 miles down river in case of emergency and two more cars about 18 miles away. Even though the distance doesn't seem far, the meandering river would take us at least 20 miles before we hit the first car and another 10 or 15 to the take-out point. While we were busy with the cars Howard caught a 7%-pound channel catfish where Skull Creek meets the Calamus.

Finally we launched our two aluminum and one canvas rigs and started floating into the tranquility only a canoe can find on a stream. The current drifts the boats along, opening a new world of scenery. Wild animals are more curious than afraid.

The spell was broken by a fin waving above the shallow waters near shore. Seeing carp triggered Karl and Gerald into action. Both wanted to get in licks with their fishing bows. Gerald and Howard moved their canoe in closer, but the fish spooked into deep water before they got into range. Karl had the same luck. Both were ready, however, if any more came into view in the shallow areas.

"Bloody Creek ahead," Gerald yelled a few minutes later, as we rounded a bend.

I had heard a lot about this creek so Wayne and I turned our canoe into the (continued on page 26)

FIRST-TIME BUCK

by Gene HornbeckTHE BUCK antelope silhouetted on the hilltop only 20 minutes before was nowhere to be seen. Making the last 200 yards of my stalk on belt buckle, I had crawled completely around the hill and found nothing. Nor was he in any of the nearby valleys. But he had to be there—somewhere.

My target hadn't seen me except from about a half mile out when I first put the glasses on him. This was my first antelope hunt, and it looked like it was going to begin with a bang. I had left Oshkosh 30 minutes before dawn and drove north into the big grass hills of Garden County's cattle country. Cutting onto a Sand Hills trail, I had only gone a short distance when I spotted the buck in the dim morning light.

Quickly loading the .220, I grabbed the binoculars and began a hike to narrow the distance between us. I cut down a long valley that led roughly to the east toward the buck. My rifle wasn't particularly made for antelope hunting, but with the terrific velocity of the 48-grain, soft-point cartridge an antelope would stay put if neck shot. The big-barreled rifle was rigged with a 2%-10 variable scope for pin-point shooting. Considering the .220, I set a maximum of 300 yards on my shot.

Rifles that work well on the pronghorn are many, but the flat-shooting calibers such as the .244, .243, .270, .257, .250, and .264 are preferred. My use of the .220 was an experiment, but I was confident that the little hot rod would deck the pronghorn if I selected my shot and placed it where it should be.

After making the stalk and checking from my prone position for any signs of the animal, I finally stood up. There was my target. He was exactly where he had been before. I was the one that had goofed, coming up the wrong hill.

The shock of seeing the pronghorn at about 500

yards made me crouch instinctively. I could just

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

make out his head above the hill from my kneeling

position. He had his eyes glued on me. I was pretty

sure I could hit him from even this distance, but

knew there would be the chance of getting a poor

hit and a crippled antelope.

make out his head above the hill from my kneeling

position. He had his eyes glued on me. I was pretty

sure I could hit him from even this distance, but

knew there would be the chance of getting a poor

hit and a crippled antelope.

Curiosity often kills an antelope. Although fleet-footed and blessed with keen eyesight, the pronghorn usually makes the mistake of waiting just a little too long to satisfy his curiosity. I was taking advantage of this trait on the one I was stalking.

My target stood frozen, watching me. How could I get in closer? I certainly couldn't get up and try to crawl on him. Maybe I could give him a false sense of security, then bust him. Standing up in full sight of the pronghorn, I walked around in a circle a couple of times, then walked away. Glancing over my shoulder just as I passed below the rim of the hill, I saw the curious critter was still watching me.

"Stay there," I thought hopefully. "Just give me a few minutes to drop down into the valley and get to the base of your hill and we'll talk business."

I fairly ran down the hill onto the valley floor, then did an about face, and began a hopeful stalk to get within range. The wind was hushed with the coming of sunrise, just a few minutes away. My legs began to ache as I crouched lower to remain out of sight. A sudden whirring and cackle startled me as two sharptails took wing off to my right. Would they spook the buck? There was no way to find out until I got into shooting position.

At the base of the hill I dropped into a prone position. The heavy morning dew soaked through my pants and jacket as I elbowed my way up. Being wet and "slightly" excited caused more than an occasional shiver to zip up my backbone. Halfway up, I figured I would be able to crack the buck by raising slightly.

Cautiously I raised to a kneeling position, expecting to see my target. Once again the buck was missing. Dropping down again, I crawled around the hill, hoping the pronghorn was sneaking out and had stopped enroute. The sun hung half submerged on the horizon from my position on the west side of the hill. Looking into it made picking out an object difficult.

"Another bad stalk?" I asked myself. "Keep going. You can't stand up now before you make a circuit of the hill. The buck could be just around the next bend."

I squinted into the rising sun, constantly searching the hillside ahead. Then, as if he had grown out of the ground, there was my buck. He had evidently heard me or whiffed enough scent to make him wonder what was going on. The pronghorn was pussyfooting parallel to me and was outlined by the red glare of the rising sun.

Roughly 100 yards divided us and the shot would be uphill. It had to be quick when I raised up. The tall grass hid me enough so that the buck was craning his neck to better see the danger that threatened. I inched the rifle forward, raised on my elbows, and swung the scope on the animal from my low position. To make matters worse, he began to drop farther down the far side (continued on page 32)

AUGUST, 1962 7

Portrait OF A DOG

Always a hunter, ever a friend, he's ready when chips are downTHE TIES that bind man and dog could not be stronger than those between the hunter and his canine friend. It has been so for countless years, and it will be so in the future, the animal teaming up his natural talents with those of his master to bring home game.

This team has been a long time in the making. Centuries ago hunters recognized the various species' specialties. Through careful breeding to get the best qualities of each, the modern hunting dogs evolved, a process still going on today.

In a prime scatter-gunning state like Nebraska, dogs naturally play an important part in the hunting picture. Because of the diversity of game, many breeds are called into play. Only the more popular breeds can be considered here. State hunters boast some of the finest sporting canines going, many of them copping top honors in regional and national field-trial shows.

8 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

The variety of names and working methods can be confusing to the neophyte. There are two distinct classes of sporting dogs, the gun dogs and hounds. Gun dogs are in turn broken down into pointers, spaniels, and retrievers.

Pointers came about through years of selective breeding. Man took advantage of a dog's habit of pausing a moment before springing on game. Through careful breeding, this momentary hesitation became a rigid point as is beautifully exemplified by the English pointer. The Englishman is every inch a gun dog, put together for speed and endurance. Primarily a quail dog, the big hunter can also be worked on grouse or pheasants.

The German short-haired pointer is a good all-around hunter. Because he works closer to his master, he does better on pheasants. This freckled short hair is a staunch-pointing bird dog and a proved retriever on land or water.

Two up-and-coming short hairs, the Weimaraner and vizsla, are getting special attention from many Nebraska scatter gunners. Both have been heralded as real all-around dogs. The Weimaraner, a German import, is one of the larger German pointers. Hungary's vizsla meets the need of those hunters who like the English pointer but prefer a dog who works in a more limited range.

Setters could well be the earliest of the pointing

breeds. They got their name from the way they "set"

or pointed on birds while the birds were flushed and

driven into the nets. The most popular setters in

10

Nebraska are the English and Irish breeds. Those

handsome Irishmen who have not been spoiled by

bench-show enthusiasts are effective upland getters.

Both of the long hairs can take plenty of abuse in the

field. Though known primarily for their pointing

abilities, they sometimes can be trained to retrieve.

Nebraska are the English and Irish breeds. Those

handsome Irishmen who have not been spoiled by

bench-show enthusiasts are effective upland getters.

Both of the long hairs can take plenty of abuse in the

field. Though known primarily for their pointing

abilities, they sometimes can be trained to retrieve.

Spaniels get their share of attention in this bird-conscious state. The Brittany, the only spaniel to point game, is popular among many sportsmen. The Brittany's gait is more like (continued on page 30)

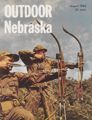

BOW AND ARROW FUN

by Wayne Tiller Bowing's booming in Nebraska, a year-round, all family sportYEAR-ROUND HUNTING may seem farfetched to some but to an ever-growing group of sportsmen, it's a reality. These are the members of the state's increasing army of hunters that stalk their game with a weapon with a most romantic past, the bow and arrow.

All through the year these modern-day longbow-men practice on field-target ranges that simulate hunting conditions. They do everything from shooting around trees and brush to using big-game animal pictures for targets. Shots are uphill, downhill, across ravines, and over knolls. They know that when a rabbit or deer is sighted on a hunt, it will most likely be in some kind of cover. With this kind of practice, the archer can cope with any situation.

The whole family is usually involved in field archery. The sport appeals to all ages since it is based on the skill of the archer to pull a bow and shoot an arrow 50 to 80 yards into an area only a few inches in diameter. From the kids to the elders of the family, they all enthusiastically vie for the chance to shoot a round of targets.

Throughout the state more and more clubs are being organized. Field ranges are being laid out near

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

many communities. These are similar to golf courses,

except there are 28 targets. Here the family can shoot

a round, then sit down to supper on the picnic

grounds that are usually close by. This is family

fun and companionship that is not usually associated

with hunting sports.

many communities. These are similar to golf courses,

except there are 28 targets. Here the family can shoot

a round, then sit down to supper on the picnic

grounds that are usually close by. This is family

fun and companionship that is not usually associated

with hunting sports.

Knocking down points substitutes for bagging game during the off-season hunting. Local tournaments get the ball rolling soon after the snow melts enough to allow shooters on the ranges. This year interest in the numerous clubs throughout the state was especially high, since the first Midwestern Field Archery Tournament of the National Field Archery Association was to be held at Long Pine in late June. Archers from throughout the state were anxious to show their ability at the bowmen's showdown.

Practice paid off. After IV2 days of shooting at 84 targets, the Nebraska archers showed their guests that this state is up and coming in the bow-and-arrow world. Home-staters competed against contestants from North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Kansas, and walked off with 34 of the 56 awards. To help the visitors remember the meet each family was given a Nebraska beef steak and an honorary membership in the NEBRASKAland Cowpunchers Association.

As an indication of the family ties even in competition on this level, consider the plight of two contestants. Luther Home of North Platte placed only fifth in his shooting class while his wife, Bernadine, took first, and son, Richard, grabbed third in their respective divisions. Irvin Booze, also of North Platte, took a beating, too. Wife, Clara, and daughter, Carol Ann, took top honors while he placed seventh. Dan Smart of Omaha and Vernon Bishop of Fremont had better luck, each taking home gold medals while their wives had to settle for second-place awards.

Come September, though, many of these archers that stress form in the tournaments will forget the formalities and excitement of competition and start stalking live targets. Not only can these arrow marksmen cash in on a deer season that will run from September 15 through December 31, excluding the rifle deer season, but other game as well. The better archers will try their hand at certain upland and waterfowl species. Rabbits and squirrels are also available in season and varmints can be taken anytime. Bow fishing is also becoming popular, with both rough and game fish now part of the archer's bag from April 1 to December 1. These smaller targets call for pinpoint accuracy from the archer.

But the big attraction will still be the unlimited supply of deer permits available and the 99 days of hunting. There is no reason why Nebraska bowmen shouldn't come up with the highest hunter success ratio in the nation as they've done in the past.

Success with a longbow comes from plenty of practice on a field range or on similar targets. Most bowhunters will tell you that practice is much more critical here than in rifle shooting.

The number of hunters in the state combined with their interest and enthusiasm about the sport has brought about the formation of a deer-bowhunter's club called the Prairie Antlers. To become a member, the archer has to kill a deer with bow and arrow and record it with the club. Although still not completely organized, the group hopes to establish state archery deer records based on the Pope and Young system similar to the Boone and Crockett records.

Realization of the chance to get more enjoyment out of hunting, the excellent deer-hunting success ratio here, and the family competition and companionship are making field archery one of the fastest-growing sports in Nebraska.

THE END AUGUST, 1962 13

NEBRASKAland by Bus

Hop aboard for six days on 1,450 mile vacation trailNOTHING CAN quite match a guided bus tour for an easy, effortless way to see and enjoy the NEBRASKAland scene. All of the state's scenic, historic, and recreation sites unfold as you travel the great circle route, the 1,450-mile, six-day trip, a rare experience for those who have yet to discover NEBRASKAland's impressive list of vacation attractions.

Four Nebraskans—Miss Ruth Fox and Mrs. Clara

Fox of Geneva, Miss Emma Benes of Wahoo, and

14

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Miss Edna Miller of Omaha—had such an opportunity

in June when they rode a Lincoln Tour and

Travel Agency bus on a conducted tour of the state.

Theirs was not a much-publicized tour of dignitaries

nor the grandiose trek of recent large groups, but

a typical outing taking in typical attractions. What

they saw and did and their reactions and comments

during the week-long trek give an idea of what the

future holds for tourism in Nebraska.

Miss Edna Miller of Omaha—had such an opportunity

in June when they rode a Lincoln Tour and

Travel Agency bus on a conducted tour of the state.

Theirs was not a much-publicized tour of dignitaries

nor the grandiose trek of recent large groups, but

a typical outing taking in typical attractions. What

they saw and did and their reactions and comments

during the week-long trek give an idea of what the

future holds for tourism in Nebraska.

Tourmaster Bill Carley introduced the ladies to world-famed Pioneer Village at Minden on the first day of the outing. After marvelling at the vast array of western Americana collections, the group headed north and west, taking in the Pony Express Station at Gothenburg and Fort McPherson National Cemetery south of Maxwell before reaching Ogallala, the Monday night stop. Fort Kearny near Kearney, and Scouts Rest Ranch at North Platte were inspected.

The four women enjoyed the first day and their brush with Nebraska's Wild West past. Fortified with facts about the overland trails, they were anxious to see the famed landmarks on U. S. Highway 26.

After taking in mammoth Lake McConaughy north of Ogallala, the ladies craned their necks for a look at Ash Hollow and the historic buttes that lay beyond. They were in pioneer country, following the trail of mountain man and '49er, Saint and sodbuster.

Windlass Hill, Ash Hollow, and Ash Hollow Cemetery were all inspected, each site giving a new, unique look at life on the trail. Courthouse and Jail Rocks got a close look-see as did Chimney Rock, the most famed site on the Oregon Trail. Once in Scottsbluff, the group headed for the national monument and the scenic drive to the top of the historic bluff. After the museum was inspected, the women were anxious to see the buffalo and elk at Wildcat Hills recreation area.

Tuesday was the most active day of the excursion and perhaps most enjoyable to the tourists. The

AUGUST, 1962

15

scenery on these stops is spectacular and varied.

Historically, it is hard to match anywhere, either

in Nebraska or the rest of the West. After spending

the night in Scottsbluff, the group headed for the

fossil quarries and Harold Cook's ranch to the north.

Due to rain, the women were unable to see the fossil

beds but did have a chance to visit with Dr. Cook.

scenery on these stops is spectacular and varied.

Historically, it is hard to match anywhere, either

in Nebraska or the rest of the West. After spending

the night in Scottsbluff, the group headed for the

fossil quarries and Harold Cook's ranch to the north.

Due to rain, the women were unable to see the fossil

beds but did have a chance to visit with Dr. Cook.

Bill Carley headed his compact touring rig toward the cool vista of the ponderosa and butte-covered Pine Ridge. Beautiful Sowbelly Canyon was enjoyed by all. Once through the twisting drive, the women found themselves at Fort Robinson, famed frontier post where the Indian wars began and ended. The state park, headquarters for the third night of the tour, boasts two museums, one telling of the frontier post and the other featuring fossils found in the nearby Badlands. The weird area was on the sight-seeing agenda, but rains had made the roads to the area impassable.

Thursday saw the vacationers up early to take in more Pine Ridge scenery, this time the attractions around Chadron. After1 visiting the old Museum of the Fur Trade there, Carley pushed on to Valentine to take in Snake Falls and Fort Niobrara. The post is now a national wildlife refuge where buffalo, longhorns, deer, antelope, and prairie dogs can be seen from the comfort of car or bus. Smith Falls was passed by, due to poor roads.

The following morning the tour left Valentine for Niobrara State Park. Here the ladies rode an old paddle wheeler across the Missouri and later saw hundreds of fish congregated below Gavins Point Dam. From there, the bus pushed on east to Ponca State Park where the group stayed Friday night. After a leisurely morning in the wooded bluffs at Ponca and a drive to South Sioux City, the ladies were ready to take in a powwow at Macy. Unfortunately, the Omahas were unable to put on a dance for such a small group, much to the disappointment of the travelers.

The trip was over. In the short six days, the four

women had seen a lot of NEBRASKAland. Bill

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Carley's passengers agreed that the long trek was

an exciting one and full of many memories. Among

other things, the group felt a new-found pride for

their state. All were pleased with the number and

variety of attractions they had seen during the trip.

Each had her favorite sites.

Carley's passengers agreed that the long trek was

an exciting one and full of many memories. Among

other things, the group felt a new-found pride for

their state. All were pleased with the number and

variety of attractions they had seen during the trip.

Each had her favorite sites.

Miss Miller liked Pioneer Village, Scotts Bluff National Monument, and Chimney Rock, while Miss Benes was impressed by the ferry ride, the fish below Gavins Point Dam, and Sowbelly Drive. The varied scenery got Miss Fox's vote, but she thought that Sears Falls at Fort Niobrara was outstanding. Her sister-in-law liked the Museum of the Fur Trade, Snake Falls, and the ferry ride.

But all had reservations. All agreed that there is a need for better eating spots, believing that good food is as much of a high light as the scenery itself. They felt that lodgings for their small group were adequate but questioned facilities for large parties.

Bill Carley, commenting from the standpoint of the private operator trying to develop a business around Nebraska's many tourist attractions, had some interesting observations. Better roads and better access are needed right now as are adequate markings to key attractions. The Badlands, fossil beds, and Smith Falls become inaccessible with wet weather. Some sites need interpretive signs, especially those with historic significance.

The trip proved many things, however. First, people are willing to spend time and money to see NEBRASKAland attractions, even though some of these spots are at present underdeveloped and uninterpreted. Carley's passengers would agree that theirs was money well spent. The four women reflect an awakening of more and more Nebraskans to their state's many attractions. They went one step further than most, however, in that they took time out to see a great hunk of Nebraska's tourist real estate.

This awakening and resulting pride in Nebraska are the basis for any tourist program. Much of it has been caused by the Game Commission and the Governor's office. But state agencies can go only so far. Once the interest has been fostered and promotion begun, it is time for private interests to move in to develop and reap the returns of individual attractions.

Recent state-wide tours of Nebraska vacationland have been eye-opening, not only to those who accompanied the governor, but to the four ladies as well. All who have participated have discovered a tremendous diversity of scenic, historic, cultural, and recreation attractions, attractions that every Nebraskan can be proud of. They have also learned something else. The realization of a full-fledged tourist industry depends on the effort of every Nebraskan.

THE END AUGUST, 1962 17

BACK-YARD FISH FRY

Fire up the charcoal grill and bring on the creel, it's outdoor chef timeTHE FISHING TRIP IS over, and the catch packed away in the deepfreeze. Occasionally, Mom will prepare some of the fish on the kitchen range. But something is missing. The fish don't taste the same as they did at that streamside campfire. There's a lack of crackle to the browned coating—an absence of that locked-in whisper of wood smoke. It's just another fish dinner.

But this doesn't have to be the fate of your catch.

Move out into the back yard and let the family

barbecue grill substitute for the campfire. Here you

can recapture some of the outdoor glamour of a

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

camp meal, and at the same time experiment with

a few of the many outdoor ways of preparing fish.

camp meal, and at the same time experiment with

a few of the many outdoor ways of preparing fish.

Naturally, your first thought is to fry it. Put a spoonful of butter in a heavy iron skillet or a griddle placed directly on the coals. While it's heating, dip the fish in a mixture of egg and milk, then roll it in a cup-to-cup mixture of flour and cracker crumbs seasoned with salt and pepper.

The fish will absorb grease unless the skillet is nearly smoking hot. It will also absorb grease if, once cooked, it is allowed to remain on the griddle while it cools.

If you have a pine tree in your yard, trim some twigs from it and put them on the serving platter. As the fish come from the griddle, lay them on the pine-branch bed to drain, and serve hot.

One campfire fish-cookery trick is an aluminum-foil pack, but remove the skin from the fish first. The skin and the very thin layer of fat beneath it hold most of the strong odor of a fish, and with foil-pack cookery particularly, these odors penetrate the meat. Hold the fish in very hot water for 15 seconds and the skin will peel off easily.

Take an 18-inch length of heavyweight foil, or a doubled section of lightweight foil, and put a square of butter on it. Salt and pepper the fish and lay it on the foil. Make a drugstore wrap, creating a miniature pressure cooker. Lay the package on the coals and let it cook for 10 minutes. The package, if properly made, will expand to football size. At the end of 10 minutes, puncture the pack with a knife to let the steam escape and dry the meat somewhat for the remainder of the cooking time. Five additional minutes should complete the cooking.

The foil pack is a good place for further experimentation. Try using a strip of bacon over the fish instead of butter. Add a thick onion slice, or stuff the fish with bread-crumb dressing to which a few drops of liquid smoke have been added.

Grilling the fish over the open coals will approximate campfire cookery most closely. To lay the fish directly on the grill is a mistake, however. It will fall apart when you try to turn it. Place the fish inside a fold of aluminum foil, then simply roll the fold over to turn the fish.

If you have good clay in your neighborhood, try baking the fish in mud. Mix the clay with water to make a heavy mud. Leave the skin on the fish and encase it completely in a iy2-inch layer of mud. Lay the mudpack on the coals, raking them over it. Let it bake for an hour, then crack the clay away with a hammer. The skin of the fish will peel away with the clay, leaving the flesh flaky and toothsome.

Serve the fish with a tartar sauce if you must, but to outdoorsmen nothing points up the outdoor taste better than a sprinkling of plain lemon juice.

These few suggestions should help you get started at campfire fish cookery in your back yard. Later on you will want to expand your craft to still more exotic methods of preparing your catch. For now, your first major step is to wheel out the old charcoal grill, and get busy.

THE END

MALONEY

Tri-County built for irrigation but makes mecca for fun seekersCOUCHED IN THE grass-covered hills south of North Platte, Lake Maloney offers exciting action for every member of the outdoor family. Maloney boasts a diversity that makes it one of the most popular outdoor fun spots in west-central Nebraska. Prime fishing, boating, water skiing, camping, and picnicking are all here for the enjoying.

Turning south on U. S. Highway 83 at North

Platte, you start a lengthy climb up into the hills,

and notice the long gleaming tubes that carry water

down to the hydroelectric plant below. Topping the

hill and turning into the area, Maloney's beauty

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

spreads out before you in a sea of green shade and

blue water.

spreads out before you in a sea of green shade and

blue water.

Grab a rod and reel and bait up. These are hot fishing waters. Here walleye and white bass take top honors on a year-round basis. The 1,650-acre lake is rated as one of the best walleye producers in the state, giving old favorites like McConaughy a race for the angling honors. Fishermen who have tried the big lake are anxious to return again.

One of the best walleye spots is in the underwater mouth of the inlet channel. Walleyes often congregate in this gentle bottom current and are easy prey for a hook draped with a gob of worms or a frisky minnow. White bass are also caught here and across the lake at the canal outlet.

This year walleyes again went on their spring hitting spree around the inlet and west of Scout's Island, and anglers took home a number of fighters that weighed around eight pounds. One lunker tipped the scales at 11 pounds, 8 ounces. They were hitting minnows, worms, crawdads, and artificials. In mid-summer the action slacked off but is expected to start again in the fall.

But Maloney fishing isn't limited to walleyes. Catches of catfish, largemouth bass, crappie, northern pike, and perch are not uncommon. Occasional crappie runs during the spring have been known to convert walleye enthusiasts in quick order.

Although much angling is done around the 14 miles of shore line, boaters find Maloney one of the better lakes for a variety of water sports. Five launching ramps strategically spotted around the lake offer access on the northeast, southwest, and south sides. Skiers have little trouble finding lots of elbow room.

Traveling the Platte River Valley between Lexington and North Platte, you might find it hard to believe such a fun spot exists in the hills to the south. Water from the Platte River has been borrowed and channeled there for irrigation and power generation. From the granddaddy of the reservoir chain, McConaughy, water flows through open ditches and underground pipes into Sutherland Reservoir. Then it winds its way 21 miles to the east and empties into Maloney.

Pulling into the picnic area kids immediately head for the various pieces of playground equipment available. Here they can romp and play on the swings, merry-go-round, teeter-totters, and horizontal bar set while the oldsters are busy fishing.

After exploring all the lake has to offer, bring out the food and have a picnic at one of the well-kept sites. Tables, fireplaces, drinking water, and toilets are here to make your stay a pleasant one, whether it be for an hour or a week.

At sundown spread your tent under the sheltering elms on the campground. Crickets and frogs start their evening chorus for you and an owl hoots his eerie wail from a nearby tree. You'll find sleep comes easy in the fresh cool air.

If camping doesn't appeal to you, cabins are available for your convenience. Frontier Resort on the southwest shore furnishes comfortable lodging for a day, weekend, or whole vacation. Numerous motels and other accommodations are just a short drive away in North Platte. Other than lodging, the resort and the Inlet Cafe on the northwest shore both offer food, groceries, fishing tackle, bait, boats, and many other supplies.

Perched in the hills south of North Platte, you'll discover the tree-shaded, restful oasis of Lake Maloney. Whether your brand of fun is fishing, boating, camping, picnicking, or just lounging under a shady tree, make Maloney a must-stop on your next weekend outing. You'll be glad you did.

THE END AUGUST, 1962 21

Camper's BEST FRIEND

by Lou Ell Plastic sheeting could be lifesaver, ground cloth, canteen, or even bathtubMORE AND MORE outdoorsmen are discovering the wide variety of uses of a plastic tarpaulin. Lightweight and inexpensive, the plastic tarp will not replace its rugged canvas cousin, but it can serve the camper in many ways. As a sleeping shelter, a waterproof ground cloth under sleeping bags, or a rain cover for firewood or camp gear, it's one of the outdoorsman's handiest items. And it can also come into its own in numerous offbeat jobs like carrying water, making an emergency raft, or even a bathtub.

Basically, the tarp is no more than a 10-foot square of heavyweight plastic sheeting, available from most hardware stores or lumberyards. To fasten, tie cords to it, gather the material around a small, round stone, and attach the cord piece with handy slipknot.

A small rubber ball from a child's "jacks" game and a shower curtain ring provide a more refined type of cord attachment. Place the ball under the material, slip the loop over the ball with the plastic between, and draw the narrow neck of the loop under the ball. Tie your cords to the ring. This easily adjustable fastener can be moved quickly to any part of the tarp.

If you want a deluxe-type tarp, weld army-surplus nylon parachute cord into its outer edge.

Welding the plastic is a fairly simple operation. Tack a

one-inch board, narrow edge up, to your bench. Cover

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the edge of the board with some heavyweight aluminum foil.

the edge of the board with some heavyweight aluminum foil.

Fold the edge of the plastic sheet over the nylon cord, lay the fold on top of the foil-covered board, and place another strip of foil on top. Weld the plastic by pressing it gently with an ordinary electric iron set at low silk heat. Allow the plastic to cool completely before removing the foil.

A word of caution. Too much heat will ruin the seam, too little won't fasten it. Experiment with scraps of plastic until you obtain the proper temperature for a firm seal.

Cut a small opening at the hem edge wherever you want a tie loop, and pull out a loop of the nylon cord. Tie or sew the loop into itself. When you get around to the starting point, sew the ends of the nylon cord together for an endless loop before you make the final seal. A ridge rope can also be welded through the center of the tarp.

The tarp folds up into a pocket-sized bundle, which can be stored in a little space. What's more, it can be folded up wet and stored for days without danger of mildew or other damage from the damp. To protect the tarp during carrying and storage, slip it into a small cloth bag.

The uses of this handy plastic tarp are endless. With a little imagination, you can make numerous items for more comfortable outdoor living. Why not add it to your outfit now?

THE END

GRADUATION CRAPPIE

Trading diplomas for tackle led to top fishing thrills Larry A. RichardsTHE TRUNK door slammed down, "Pete" slid under the wheel of his '48 Ford, and a not-to-be-forgotten fishing trip was about to get underway. Our destination, Swanson Reservoir, just west of Trenton in the Republican Valley.

"Think we forgot anything?" I asked as I mentally tried to recall the endless amount of gear we had stowed in the car. Sleeping bags, rods, tackle boxes, a flashlight, bait, food, and what seemed like a hundred other articles had been loaded. This was a climax to four years of high school. Only a scant hour ago Harold Peterson and I had hurriedly changed from caps and gowns into relaxing clothes and made ready to depart on our planned reward.

Everything was just right on that May morning in 1957 when we left Curtis, traveling south to McCook on U.S. 83, then west on U.S. 34 to the lake. Ahead was a bright sun, no wind, the smell of spring everywhere, and two days to relax and enjoy ourselves.

Early reports said that the crappie were making their annual spring run. We were ready for them. A few hours seining the day before had given Pete and me two bucketfuls of small minnows. In addition, our tackle boxes were brimming with new lures and spinners we had been collecting throughout the winter.

Surprisingly, few people were fishing when we got to the lake, and Pete and I found one large pocket deserted. The water was fairly deep and was spotted with trees and brush. These had left the shore line to become part of the lake with the advent of spring rains. This was the place to start.

Storing our two minnow pails in the shallows

we turned to getting our gear from the car. I

had decided to try my five-foot, light-action casting

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

outfit. The line was five-pound-test monofilament

with one split shot attached for weight. Pete had

rigged up his eight-foot fly rod and was ready to go.

outfit. The line was five-pound-test monofilament

with one split shot attached for weight. Pete had

rigged up his eight-foot fly rod and was ready to go.

"Here's luck," I told him, as I headed toward the end of the pocket for my first try. This was the first time either of us had gone after crappie on a full scale and were dubious about the best methods of taking them. I cast out about 30 feet a couple of times and slowly retrieved the minnow. But there were no takers. At this rate, I mused, I'll ruin a lot of minnows if nothing else.

I lifted the minnow toward the surface to see if he was still alive and kicking. I was just ready to pull him out and make another cast when the water boiled and I had a taker. Setting the hook, I reeled in the first crappie of the day. Glancing down the shore line, I noticed Pete was still making long casts and slow retrieves.

"Work closer," I called to him. "I got one right next to the edge in about a foot of water."

Nodding his head, he dropped the line out about six feet from shore next to a large stump. I was just putting on another minnow when I heard a whoop. Pete's rod bent surprisingly, and he pulled in what looked like a twin to mine.

Baited up again, I dropped the line out at the end of a submerged willow. The bobber floated quietly for about 30 seconds, then jumped twice, and headed for the trees. I jerked back and hauled in an empty hook. Cautioning myself against buck fever, I rebaited and dropped the line in almost the same position. It only took seconds and the whole procedure was repeated again, including the missing minnow. Pete was catching them regularly now. His smaller No. 6 hook was doing the trick, so I hurried to the car, grabbed my tackle box, and started rummaging. Finally finding a pack of leaders with No. 6's, I quickly changed and was back in business. Again I returned to the same spot and a few seconds later, banked my second crappie.

After that there was no let up. We pulled them in one after the other with amazing regularity. Neither of us noticed a black, boiling mass of clouds accumulating in the northwest until it was almost too late. The wind was already starting to slap small waves against the shore line.

OUTDOOR Nebraska proudly presents the stories of its readers themselves. Here is the opportunity so many have requested—a chance to tell their own outdoor tales. Hunting trips, the "big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor impressions—ail have a place here. If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, OUTDOOR Nebraska, State Capitol, Lincoln 9. Send photographs, too, if any are available."We'd better load up and get the car back to the highway," Pete yelled. "I don't want to get stuck down here."

Reluctantly we gathered our gear and had no sooner started up the narrow road before the rain pelted down. Pete and I decided to wait for awhile and see if it would clear. It rained for nearly an hour without let up, and we were faced with the prospects of sleeping in Pete's car.

"I've an aunt and uncle living in Culbertson," I told Pete. "Let's drive back there, clean our fish, and wait this out."

As we slowly drove back toward Culbertson, I got to thinking about our fabulous catch. Less than four hours of fishing had given us both nearly our limits and we hadn't moved out of the pocket.

The rain hadn't stopped by the time we reached my Uncle Norris Sensil's home in Culbertson. Once the greetings were over, Pete and I turned to the task of cleaning fish. Both of us were quick to agree that catching was a lot more pleasant than cleaning.

After washing up and enjoying a delicious meal, Pete and I decided that nature wasn't going to cooperate with us, and with persuasion from our hosts, agreed to spend the night and leave again for the lake early the next morning. With the alarm set for 4 o'clock, Pete and I crawled into the sack and quickly fell asleep.

I pulled myself out of bed with the first clang of the alarm, turned it off, (continued on page 31)

AUGUST, 1962 25

FLOATING the Calamus

(continued from page 5)mouth of the Sand Hills creek and paddled up a short way. The water was as red as blood. Actually there's an unusual algae that causes the crimson color but some of the local residents have their own stories on its background.

Wayne and I paddled hard to catch up with the rest, once back on the Calamus. In the distance we could hear them yelling, then saw the trouble, a bridge with only a few inches clearance. One mistake could mean a dunking or a bashing against a bridge abutment.

"Head for the right side," yelled Howard. "The other's full of brush."

Wayne ducked as the current pulled the canoe under the bridge. But the light craft drifted into the center piling and threatened to roll over. I pushed away from the big timber with my paddle just in time to lay back, watch the bridge go over inches above me, and hope my push was enough to keep us out of trouble. Luckily we came shooting out the other side still upright, only inches from the threatening piling.

With the bridge, three barbed-wire fences, and the wild ride through the swift rapids under our belts, we were ready for a noon break and something to eat. From the sand-bar picnic spot I could hear in the distance a pheasant cackle that mingled with the many other peaceful bird, wind, and river sounds. Dry tuna sandwiches never tasted better.

Lunch left our water jugs nearly empty so part of the scouting in the afternoon would have to be devoted to finding a good fresh-water spring. Several miles downstream Wayne spotted a spring and dug out a collecting basin in the gravel. The water was cool, fresh, and plentiful.

Occasionally throughout the trip we would find oxbow cutoffs and water areas off the main course. These offered angling and bow fishing. Although success was limited to some sightings and near misses with an arrow, these cutoffs often yield bass, crappie, catfish, carp, and a few northerns.

Numerous land animals continuously distracted

our attention. A mule-deer doe and two fawns

spooked from a wooded slough and two more does

watched the canoes' progress from a distance. A

big beaver rolled out of his bank den just a few feet

away, a muskrat slipped into the water of a slough,

and a great blue heron stayed two hops ahead of us

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

all afternoon. Always there were small chattering

birds in the brush and numerous animal trails leading from the water.

all afternoon. Always there were small chattering

birds in the brush and numerous animal trails leading from the water.

This lure of finding out-of-the-way fishing spots and getting close to wildlife in their own environment draws a few Nebraskans to the streams and rivers each summer to try the floating game. But the water avenues haven't been fully explored.

A constant and dependable flow of water seeping out of the Sand Hills makes the many streams that headwater in that area perfect for floating. Sand Hills streams that offer good floating, other than the Calamus, are the North Loup, Middle Loup, South Loup, Dismal, Elkhorn, and Niobrara rivers and Gordon Creek. The Niobrara and its tributaries are often tricky with occasional fast water and rapids.

When going into unknown water, check with the people that live in the area, especially those that own property bordering the stream. You should obtain their permission to pass through their land, especially if you expect to camp and fish along the way. They can also give you valuable firsthand information.

All too soon the float trip was over. Our cars were waiting near two abandoned sand pits that would be our campsite the second night. Though the fishing looked promising, our interests were more in the line of fried frog legs and catfish, then sack time.

As I wearily crawled into my bedroll that night, the sounds of the Calamus drifted into my tent. It was a siren call, one that would lure me to the Sand Hills river again.

THE END

PLAN AHEAD

Ask now, hunt later is slogan of state s thinking sportsmenIN APPROXIMATELY three months, Nebraska's state-wide rifle deer season gets into full swing. Thousands of permit holders will be heading into prime deer country, and for those who have staked out their hunting territory with permission of landowners, the season could be a good one. But for those who didn't, the story can be different.

The access question looms large in the minds of Nebraska's deer hunters. Though the deer are here, most are found on privately-owned land. Both law and common courtesy require that a hunter get permission before hunting on private property. For years it has been proved that the smart hunter makes his hunting arrangements even before he sends in his application for a special permit. Now is the time to make those arrangements, not on November 3.

Each year Game Commission personnel working at check stations during the deer season are besieged by eager hunters asking the same question, "Where can we hunt?" It might seem like a foolish question, but it is one that is asked again and again and one that with foresight, could be completely avoided.

Nebraska is among the more fortunate states in that there is no great access problem here. Most landowners are glad to give responsible hunters permission to use their land as long as the request is made in advance. Last year, for example, a hunter sent letters asking permission to five landowners. With the letters he included a post card where the rancher could check yes or no in answer to the request. Of the five sent, three were returned saying yes.

Of the hunting units, only landowners in the Upper Platte and Omaha units tend to be reluctant to open their land to hunters unless they know them. Some of those in the Upper Platte have had bad experiences in the past and in the Omaha Unit, the large population creates a problem.

Even though you know no one in the unit where

you wish to hunt, there are many ways of finding

landowners who can be contacted in advance. Chambers of commerce in the unit or friends who have

hunted there in the past will usually be glad to help

out. The chambers often keep the names of landowners who allow hunting on hand and will send you

such a list upon request. One letter is usually enough

28

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

to do the trick. Too, you'll often get much factual information about the area.

to do the trick. Too, you'll often get much factual information about the area.

Once you get the necessary information, write the landowner well in advance of the season, letting him know of your desire to hunt on his land. Personal contacts, although often impossible before the first day of the season, are still the best. Some hunters have found it pays to combine a fishing or another hunting trip with a jaunt to seek out a place to go deer hunting. Meeting the rancher or farmer in person will go a long way toward good relations.

If the landowner feels you're interested enough to contact him early, he'll usually be more than glad to help. But on your part there are some things to keep in mind. By sticking to a few rules of common courtesy, you can be pretty sure of finding the land open to you when you come back the next time.

Hunters in many states have learned the sad lesson that their carelessness can mean no hunting. The game is inaccessible because landowners don't want to take any more chances on having their stock and their property damaged. This isn't the case here, and it's up to the hunter to see that it never is.

Handle your gun carefully and be sure you know what you're aiming at before you shoot. Avoid damage to crops and livestock. Close gates behind you. Always insist on the same good conduct from your hunting companions. Don't ruin everyone's chances by being a careless hunter.

As the season opens, head for deer country with visions of that trophy buck in mind. But once there, don't forget the landowner. He is doing you a favor by allowing you to use his land. Do him a favor by accepting the responsibility of taking care of that privilege.

THE END

PORTRAIT OF A DOG

(continued from page 11)the pointer, even though his closest relatives are the setters. Being smaller, the "Brit" works closer and points and retrieves with equal ability when trained properly.

Though small, the English springer spaniel is all heart when it comes to hunting. He gets birds up boldly, his flushing abilities making him the choice of many pheasant hunters. When cover is dense as it often is on Nebraska's opening day, he flushes birds that would otherwise be missed. The springer works close to the gun, sweeping the field ahead like a vacuum cleaner.

The Irish water spaniel lives up to his name, taking to the water with bold dashing eagerness. Few hunters have latched on to this prized species, even though the retriever works upland game as well as waterfowl. This Irishman is strongly built but not leggy and has great intelligence.

In the retrieving group the Labrador rates highest among Nebraska sportsmen, followed closely by the golden and Chesapeake Bay retrievers. A few curly coats and flat coats are also found working here during the hunting season.

The Labrador is believed to have been used to retrieve objects that fell into icy Arctic waters from fishing boats. His endurance and stamina under such adverse conditions are still evident. Although basically a retriever, this breed can be easily trained to excellent qualities as an all-around sporting companion. Regarded also as simply a retriever, the golden is equally adaptable to training as a combined flusher and retriever.

The Chesapeake Bay retriever is as rugged as they come, and you'll find him ready to take on the most frigid waters to bring in downed waterfowl. The big dog is a natural swimmer and built for endurance. Though sometimes a bit headstrong, he retrieves both upland game and waterfowl and works well flushing game.

Hounding is fast becoming a popular sport in Nebraska, thanks to an abundant supply of rabbits, raccoons, coyotes, bobcats, and other game. Beagles are the most popular of the breeds here, as is the case throughout the nation. The small go-getter is ideal for both field and home, a perfect pet and hunter. Being small, the beagle works fairly close. When he hits a line, he opens up with a deep-ringing song that's music to the hunter's ears.

As pretty is the sound of coonhounds when they've got scent of their prey. These powerful canines have been subject to many years of breeding. The black and tans, blue ticks, Walkers, red bones, and varieties thereof have one big asset, their noses. Raccoons or bobcats, it matters little to them. They'll light out after a variety of species to make one of the most exciting and noisy hunts of the season.

Most people picture the greyhound as a dog who

knows nothing more than to chase mechanical rabbits

30

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

around an oval. Not so in Nebraska. These sight

dogs are in big demand among state coyote hunters.

Unlike most of the other sporting breeds, the greyhound has a history of over 5,000 years, the Egyptians

using the sleek dog as a regal pet as well as a hunter.

Stag and wolf hounds are also brought into play on

coyotes and many owners are cross breeding to develop what they feel is the ideal coyote getter.

around an oval. Not so in Nebraska. These sight

dogs are in big demand among state coyote hunters.

Unlike most of the other sporting breeds, the greyhound has a history of over 5,000 years, the Egyptians

using the sleek dog as a regal pet as well as a hunter.

Stag and wolf hounds are also brought into play on

coyotes and many owners are cross breeding to develop what they feel is the ideal coyote getter.

Owning a dog in game-rich Nebraska is almost the key to success afield. But ownership is more than having a hunter. Sporting dogs are great companions, a part of a team that's hard to beat anywhere.

THE END

GRADUATION CRAPPIE

(continued from page 27)and tried to drag Pete out. This proved to be real difficult, but after giving him a hard time for a spell, he finally rolled out. Taking care not to wake anyone, we crept from the house into a chilly dawn. The rain had spent itself during the night, and splotches of stars peeked through the mist overhead.

We decided to have breakfast at Trenton before going out to the lake. A sleepy-eyed waitress took our orders and Pete and I struck up a conversation with other anglers headed toward Swanson. Most were going after crappie, but we learned that bass were starting to hit fairly well on up the lake. Eager to try these other fishing spots later, we finished our breakfast and headed back to our crappie hotspot.

What had been a real producer the day before had really cooled off. We worked the entire pocket, but creeled only two crappie apiece for our efforts. We were about to head for greener pastures when, as if by magic, the crappie started biting as regular as before.

Shortly before noon Pete and I called it quits on crappie and moved farther up the lake to check the bass situation. Following the directions we'd received back at Trenton, we found another canyon almost like the first. Pete switched to a casting rod and we both started plugging. We tried everything, small spinners, flatfish, and even bait again but couldn't raise a bass. The crappie wouldn't leave us alone, however, and Pete and I succeeded in filling our limits.

By 2 o'clock we decided to close up shop and head back to Culbertson. And after two hours we had our fish cleaned, packed in ice, said our goodbye's, and headed home.

Pete and I were already planning our next trip. The rain started up again about half way to Curtis, but who cared? We had plenty of thrills, plenty of fish, and knew we would return again.

THE END Editor's Note: Larry Richards is now Corporal Richards with the Headquarter's Company of the Seventh Marines. Now based at Camp Pendleton, California, Larry is anxious for a repeat performance at Swanson.

FIRST-TIME BUCK

(continued from page 7)of the hill. I couldn't get a good target to pull on. Then the pronghorn fidgeted a little and tried to identify the strange object in the grass.

Taking a chance, I rolled to a spot 10 feet down the hill where the grass had been grazed away. This time I came up high on my elbows, swung the scope on the buck, and once again the sun burned my eyes. But it was now or never. I squinted into the eyepiece, picked up the cross hairs on the scope, brought them to rest on the silhouette of the buck's neck, and squeezed the trigger. The bullet blasted out of the muzzle with my hopes behind it.

The slug whomped home and the buck leaped high into the air. I jacked another shell into the chamber and hurried toward the fallen animal. My bullet had caught the pronghorn three inches up on the neck. The shell's terrific speed and the neck shot had killed him instantly.

It was a thoroughly soaked but happy hunter that pulled into the Game Commission check station in Oshkosh just a few minutes after 7 o'clock the first morning of the antelope season. My first-time buck was the first to be checked. I'll be trying for another pronghorn this year, but I have the feeling the hunt won't be quite as exciting as the first.

THE ENDCLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 FOR SALE: Registered Brittany spaniel pups from hardhunted parents. All ages. Vaccinated. Now is the time to start their training for next fall. Rudy Brunkhorst, Office Phone, Locust 30011, Columbus, Nebraska. THREE AND ONE-HALF-MONTH-OLD registered English setter puppies. $50 each. From top gun dogs. Top breeding, stud service. John H. Render, 3612 Craw Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. Phone 1799-3120. FOR SALE: Registered English setter pups. Farm raised. Good hunters. Also have unregistered German short-haired pups for sale. Good stock. Larry Jones, Phone 145-W, Cambridge, Nebraska. BEAUTIFUL AKC GERMAN short-haired pointer pups. Selective breeding. Dam and sire excellent gun dogs. Whelped June 5. Ed Cook, Phone 324-2279, Lexington, Nebraska. GERMAN SHORT-HAIRED pointer pups for sale. $60 each. Field-champion pedigrees. Dr. Donald Sallenbach, Gibbon, Nebraska. ATTENTION BIRD HUNTERS: White with orange pointer female, Snip, F.D.S.B. No. 664,011. Two years old last April. Hunted last fall on grouse, pheasants, and quail. Fast, hard, and medium-range hunter with nose, style, and bottom. Not enough birds here to finish her. A beautiful female with national-champion ancestors close up. An outstanding unfinished, class gun-dog prospect. Just out of season. Summer-time price, $75. Harry Stokely. Valentine, Nebraska. FOR SALE: Vizslas, Hungarian pointer retrievers. Short hair, short tail, golden rust color. Limited number of quality stock. Maggie, Z-Selle Line. Graff-Weedy Creek Kennels, Route 3, Seward, Nebraska. Phone 8677. AKC BLACK LABRADORS. Outstanding pedigrees. Some field-champion sired. Good assortment of sharp young dogs. Some started. August pups. Custom retriever and obedience training. Kewanee Retrievers, Phone 26W3, Valentine, Nebraska. BLACK LABRADOR puppies. Championship and hunting bloodlines. Sire, Marshwise Snapshooter; dam, Topsy's Peg. Price $65 at the kennel. R. C. Pancoast, 414 Douglas, Wayne, Nebraska. FISH HOOKS—5 dozen assorted, sized No. 2 through No. 10. with 7-inch nylon snells, $1. Special offer, a gross (144) assorted, $2. Hand tied. Hand Forged. Carded in carrying packs. Full refund if not satisfied. The Dayton Catalogue Company, Bellbrook, Ohio. RATTLESNAKE BOLO TIE—Send rattle and $1.25 check or money order. Will return, postpaid, embedded in clear plastic, color or choice background, oval or arrowhead shape, with slide and string attached. Rattle length limit Wz". Satisfaction guaranteed (No C.O.D.) H. L. Kitzelman, man, 2124 Grand Avenue, Omaha 10, Nebraska. STEEL CREEK STOCK FARM. Farm Vacations. Family Rates. May-November. For information, write Mrs. Gerald Snyder, Steel Creek Stock Farm, O'Neill, Nebraska.

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

COLORADO . . . Colorado's Vega Reservoir has been supplying anglers with plenty of material for fish stories. The first tale started when an angler caught a nine-inch rainbow with two mouths. The once-normal trout had developed a second mouth as a result of an injury. The second fish story came when one ice fisherman lost his rod through a hole in the ice. Later the same day, a woman angler fishing through the same hole hooked what felt like a huge trout. When she pulled the lunker in, she not only had a trout on her hook, but also the missing fishing pole and the trout that had pulled it into the water.

PENNSYLVANIA . . . There's a Pennsylvania hunter who is still trying to apologize to his Brittany spaniel. After pointing two birds, the dog locked on point the third time. As the man walked in to flush the bird, a red fox took out across the field in front of him. Just as the hunter turned to scold the dog who was still pointing, a pheasant flushed about five feet in front of the dog. Someone was pretty embarrassed and it wasn't the spaniel who had a red face.

High Cost of LitteringMINNESOTA ... In Minnesota, the old adage of what goes up must come down was reversed to read what goes down must come up. A Red Wing man in the habit of tossing beer cans out his car window was ordered to pick up the can and other debris from both sides of 7V2 miles of highway or forfeit $75. He was fined $100 for possessing opened beer in a moving car and $25 for littering the highway. He was ordered that $75 of the fine would be refunded when he had satisfactorily cleaned up the road.

Deer-Saving RadarPENNSYLVANIA . . . Highway patrolmen and their radar are not only slowing down speeders in Pennsylvania, but they're reducing the highway deer kill as well. Since the state police began enforcing speed laws with radar there has been a decline in the number of deer killed by vehicles on a straight, three-lane section of Route 422. Seems that since drivers are watching the roadside for the radar cars, speed has been cut down.

notes o n Nebraska fauna ...

STICKLEBACK

EVEN THOUGH he is no more than two inches in length, the male stickleback displays courage and daring not normally associated with the fish world. Uniquely, however, he is also a dedicated father who will go the limit in protecting his fry.

His pugnacious nature has made the brook stickleback, Eucalia inconstans, one of the most forceful guardians of young in the fish world. The stickleback group name is derived from the five or six spines in front of the dorsal fin. These quills may be locked in the erect position and are used to a great advantage during nest-guarding encounters.

This scrappy fish is found generally in the headwater areas of streams from Kansas to Maine and north into Canada. Here in Nebraska he has been reported from the headwaters of Gracie Creek in Loup County, Snake River in Sheridan and Cherry Counties, Minnechaduza Creek in Cherry County, a drainage ditch west of North Platte, Blue Creek in Garden County, the Platte River near Columbus, Long Pine Creek in Brown County, Bazile Creek in Knox County, Clear Creek in Saunders County, and Beaver Creek in Boone and Wheeler counties.

These localities satisfy the stickleback's requirements for cold, clear springs and brooks where there is considerable cover offered by a dense submerged growth of aquatic vegetation. A muck, peat, or fertile stream bottom is preferred.

Tolerance to pollution and water turbidity is extremely critical. Conversely, the stickleback's great

34

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

tolerance to highly alkaline or acidic conditions may

be attributed to his spring-brook habitat. Dredging,

ditching, and draining readily destroy his preferred

habitat and is believed to have caused a decrease in

numbers throughout his range.

tolerance to highly alkaline or acidic conditions may

be attributed to his spring-brook habitat. Dredging,

ditching, and draining readily destroy his preferred

habitat and is believed to have caused a decrease in

numbers throughout his range.

The general color of the fish varies with the locality and type of water, and except for the spawning male, dull tones predominate. The upper surfaces are olive, greenish, brassy, or brown fading into lighter hues on the sides. The undersurface is a light yellow, white, or silver.

During the breeding season, the male turns red to yellowish salmon from the snout to the back of the pelvic fins. Bluish tones may appear along the sides and on the face, and the eye develops an iridescent blue-green color that persists throughout breeding. The female does not assume any bright coloration at any time.

Internally the stickleback is different from most fish in that the organs of the opposite sex are present in the mature individual. The male possesses paired ovaries. These are apparently nonfunctional. The female has male organs that are not prominent. There is also one record that indicates the possibility of self-fertilization as a result of this arrangement.

Spawning dates for the stickleback in Nebraska are not specifically known, although it is assumed that egg-laying occurs in late spring or early summer. In spring-fed brooks in the western Great Lakes area, spawning begins about the first week of May, and is regulated to some extent by the temperature and other weather factors.

In preparation for this season the male begins building an elaborate nest of small sticks, twigs, and other pieces of vegetation. The barrel-shaped structure may be concealed on the stream bottom in dense vegetation, plant branches, or on the rocky bottom of pools where the flow of water is moderate.

When a collection of twigs and raw materials has been accumulated the fish passes back and forth over the nest with a sticky cementing substance secreted by the kidneys. Then he dives into the middle of the pile to create a front and rear entrance, and a connecting passage.

Both the inside and outside are cemented with the secretion until the nest is held securely in place by the hardening substance. Over and over the fish tests his creation by nudging it with his snout during this cementing process. Then he picks up sand from the stream bed and deposits it on the nest to keep it from floating to the surface.

Occasionally a nest may be found that is constructed by a fish simply burrowing a hole in the sand. Eggs have also been found that were apparently randomly scattered in dense vegetated areas.

After the nest is completed, the male begins his task of attracting one or more females. During the courtship he nudges his intended spouse with his snout and spines, and coaxes her into the nest to deposit normally fewer than 100 eggs. After only a few seconds the male drives the female out, often by force, and immediately fertilizes the eggs.

After the breeding process the male jealously guards the nest and young, oftentimes from his ex-mate. He also provides aeration of the eggs by his swimming or fanning movements near the nest. This is especially necessary in still-water areas.

Incubation time of the eggs varies according to the water temperature. Some eggs have been observed to start hatching after 14 days in 48° to 60° temperatures and the eyespot was noticable after only nine days.

After hatching the young stay in the nest for a few days, still under the guard of the male stickleback. As a young fry swims out of the nest the guarding adult sucks it into his mouth and squirts it back into the nest. As time passes the swimming ability of the young increases, and more and more escape the frustrated guardian. He abandons them when they are old enough to fend for themselves.

The stickleback is of little direct economic significance, although he is effective in the control of mosquitoes in some areas. He also depends on small insects and crustaceans for his food supply.

Utilization as a food fish by game species is not included in the economic importance of the stickleback. This is due to the relatively small populations, limited distribution, and the presence of the stiff spines. Some rare incidents have been reported of the spines projecting through the throat or stomach wall of predator fish.

The next time you venture into the headwater or spring areas of a stream, look for a darting glance of a brook stickleback. If you are lucky you may even spot this fighter's nest. Chances are he and his brood will both be gone, but the nest will remain as evidence of the fish's persistent parental vigilance.

THE END AUGUST, 1962 35

ANTELOPE FIELD CARE

Even after good shot, you may still return home empty-handedSINCE ANTELOPE ARE hunted early in the fall during generally hot weather, fast and thorough cooling is vital. Poor-tasting meat is not the fault of the animal, but the hunter who failed to apply proper field-care procedures.

As in the dressing of any animal, complete bleeding is the first step. Place the animal with its head downhill and cut the large blood vessels at the point of the brisket. This will leave the cape intact for mounting. If you have downed a buck, take out the male organs. Cut the skin from around them © and remove, taking care not to puncture the organs with the knife.

Next remove the entrails by cutting just through © skin from in front of the vent forward through the breastbone. Don't puncture any portion of the digestive tract. Cut around the vent and pull it into the body cavity. Work around the entrails and free the entire mass from the rib wall and backbone. Sever the windpipe and gullet just above the lungs. When completely loose, dump the entrails by rolling the carcass on its side. Be careful that none of the intestinal or gall bladder contents or hair gets on the meat. Save the liver, kidneys, and heart.

If you've got a long drive back from the panhandle ahead, skin and sack the carcass. Once through the check station, cut the legs off © sever the head, O split along the inside of the legs, and remove the skin. Quarter the carcass, sack in cheesecloth, and keep in a cool place. If possible, have the meat processed and properly cooled by a packing plant before starting the trip home. In transporting the carcass, a car-top carrier is preferred since the flow of air will keep the meat cool.

THE END