OUTDOOR Nebraska

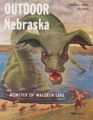

JANUARY 1962 25 cents the MONSTER OF WALGREN LAKE page-6

OUTDOOR Nebraska

January 1962 Vol. 40, No. 1 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. Greg Smith, managing editor; C G. "Bud" Pritchard, Wayne Tiller, Jane Sprague, Bob Waldrop

FISHING Hard Water

Grab spud and jigging rod and head for a productive angling season on the iceWHEN THE temperature hits zero, a new breed of outdoors-man takes over the outdoor scene—the hard-water angler. With spud, tip ups, jigging rods, ice flies, and minnows plus a couple of layers of warm duds he takes to Nebraska's lakes and reservoirs for a season of top ice fishing.

As an old-timer at the game puts it, "Ice fishing is for those that like to get away from it all for a day of productive fishing. There are no hot-rod boaters to make fishing impossible, and you can fish any spot in the lake."

He could have added that tackle is at a minimum, there are no $20 rods to buy, no outboard motors, and no tackle box full of lures. The frosting on the ice-fishing cake is the fact that for day in, day out fishing on panfish, winter angling is far more productive than midsummer. Fish such as the crappie, perch, bluegill, walleye, and northern are all active feeders in the winter.

Guide to Ice Fishing

Guide to Ice Fishing

Lakes, farm ponds, sand pits, and reservoirs around the state are all potentially good ice-fishing waters. The Sand Hills lakes offer early fishing as do ponds and pits. Reservoirs are good, but large ones sometimes do not freeze over solid enough to allow fishing except in the bays.

Here are some of the better known ice-fishing lakes in the state and the species found in them. Some are private so permission is needed.

KEY BL—Bluegill CR—Crappie WL—Walleye NP—Northern Pike SA—Sauger CF—Catfish PE—Perch TR—Trout BA—Bass 7 miles north of Ogallala TR, PE, WL 8 miles southeast of Imperial 3 miles west of Trenton NAME 1. Whitney Reservoir 2. Box Butte Reservoir 3. Lake Minatare 4. Smith Lake 5. Shell Lake 6. Cottonwood Lake 7. Fry Lake 8. Crane Lake 9. Duck Lake 1 0. Island Lake 1 1. McConaughy Reservoir 12. Lake Ogallala 13. Enders Reservoir 14. Swanson Reservoir 15. Medicine Creek Reservoir 16. Lake Moloney LOCATION 2 miles west of Whitney 1 2 miles north of Hemingford 6 miles north of Minatare 22 miles north of Lakeside, oil 14 miles northeast of Gordon, trail off of U.S. Highway 27 1 mile east of Merriman, Vi mile south on Highway U.S. 20 2 miles north of Hyannis, trail Crescent Lake Refuge Crescent Lake Refuge, oil road Crescent Lake Refuge, oil road, north of Oshkosh 7 miles north of Ogallala 7 miles northwest of Cambridge 6 miles south of North Platte SPECIES WL, CR, CF WL, CF PE, WL, NP CR, NP, BL, PE, BA CR, NP, BL, PE, BA BL, CR, NP, PE, BA CR, NP, BL, PE, BA BA, BL CR, NP, PE, BA BA, BL, NP PE, WL, NP, TR WL, CR, BA, NP WL, CR, BA, NP CR, WL, BA PE, WL, CR, BA NAME 17. Sutherland Reservoir 18. Bull Lake 1 9. Lone Tree Lake 20. Hackberry Lake 21. Watts Lake 22. Big Alkali Lake 23. Bollards Marsh 24. Holfelt Lake 25. Enders Overflow 26. Clear Lake 27. Willow Lake 28. Midway Reservoir 29. Johnson Lake 30. Harlan County Reservoir 31. Brunner Lake 32. Swan Lake 33. Willow Lake 34. Goose Lake 35. Lewis and Clark Lake LOCATION 6 miles southeast of Sutherland 1 6 miles northwest of Brownlee, oil road and trail 29 miles southwest of Valentine, trail Valentine Waterfowl Refuge, State Spur 483 Valentine Waterfowl Refuge 23 miles south of Valentine, State Spur 483 21 miles southeast of Valentine on U.S.Highway 83 1 3 miles southeast of Ainsworth, trail east from State Highway 7 29 miles southwest of Ainsworth, follow state signs on State Highway 7 28 miles southwest of Ainsworth, trail 34 miles southwest of Ainsworth 5 miles southwest of Cozad 7 miles southwest of Lexington 2 miles south of Republican City 25 miles southwest of Chambers, trail off State Highway 1 1 25 miles south of Atkinson on State Highway 1 1 32 miles south of Atkinson, trail off State Highway 1 1 31 miles southeast of O'Neill 5 miles southwest of Yankton, S.D. SPECIES PE, WL, CR, BA BL PE NP, BL, BA NP, PE, BA CR, NP, BA, BL, PE BL CR, BL, BA CR, NP, BL, BA, PE BL, BA CR, BA, BL, PE CR, WL, PE, BA CR, WL, PE, BA CR, WL, NP CR, BA, NP BA, BL, NP, CR * CR, BA, NP CR, BA CR, WL, BA, SA 4 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Baits are not hard to come by during the frigid months. The minnow in sizes to fit the intended diner is the top bait on all except bluegill. He's more apt to take the small aquatic nymphs. Artificials such as the varied ice flies have proven very good. The one depicted in the December issue of OUTDOOR Nebraska is good on bluegill, crappie, and often perch. Natural bait such as small red worms, goldenrod grubs, corn borers, and the commercially sold live nymphs are all good fish producers.

Minnows are the top bait on perch with the eye of another perch taking the No. 2 spot. This is the only species that can be consistently taken on "fish eyes". Some anglers use them with only a small hook, others use a small spoon with single hook.

Northern and walleye like a big lively shiner served to them. Artificials will work but they should be constantly jigged. Spoons are good, especially the heavy ones. The feather or nylon jig is also coming into its own on crappie as well as northern and walleye. These should be fished on a fairly limber jigging rod and worked about six inches off the bottom.

The angler should have no problem getting outfitted for a season on the ice. The jigging rod can be a commercial product or can be made from the tip of an old fly or spinning rod. Make the handle from a broomstick. Cut the grip about a foot long, measure the diameter of the butt of the rod tip, drill a hole an inch and a half to two inches deep in the end of the stick, and glue. Two screws placed about six inches apart and turned halfway into the handle make a serviceable line holder.

The jigging rod is the stand-by of the ice fisherman. It's used in jigging small spoons and feather jigs as well as for bait fishing. When fishing bait, use a very light cork and just enough lead to sink your offering. The cork serves two purposes, the minnow can move around more freely and the light cork is easily jerked under by a taking fish.

The jigging stick is used with the heavy jigging spoons. It is seldom more than 20 inches long and is just as the name implies, a stick. Having no give, it imparts better action to the spoon.

Lines on the jigging rods should be kept light. Four to six-pound-test monofilament is more than adequate. Line on the jigging stick should be just the opposite, with 20-pound-test a good choice since the stick is used on larger fish.

A tip up is the favorite of the walleye and northern pike fishermen. These are hard to find in Nebraska stores, but can be easily made. They may vary in shape but their functions are the same. The tip up should have some type of flag or indicator that pops up when a fish strikes. The fisherman can see these from a distance while he is tending the others.

Tip ups used for the larger fish should have some type of reel to allow the fish to run, giving a big one a chance to take the minnow. Many times a pike or walleye will grab the bait and run 20 feet before he stops to swallow it.

Many fishermen use their casting rods as ice-fishing outfits. These work very well when fishing bait with a small sinker and light cork.

The skimmer or strainer used to take the snow and ice out of the fishing hole can be made from a one-pound coffee can by punching holes in it. The little woman's kitchen strainer makes a good one, too, if the fisherman can requisition it.

Finding the right spot to fish on a lake can be a big problem for beginners. Trial and error still has its place, but knowing fish and fish hangouts can often save a lot of time and effort. Bluegill, crappie, northern, and bass frequent the edge of weed beds and drop offs and are seldom caught in more than 15 feet of water. Perch and walleye will follow the same patterns, but in deeper waters such as the reservoirs, are found in 20 to 40-foot-deep water.

Many fishermen trying a lake for the first time will follow a point of land into the lake and then try to judge from the visible contour where the edges of the point are underwater. The more you work at it, the more familiar the different patterns become.

Why not investigate that summer favorite now that it's covered with ice. You may find the fish are biting better now than in the summer.

THE END JANUARY, 1962 5

the MONSTER OF WALGREN LAKE

by Jane Sprague Terror reigned in Sand Hills when Giganticus reared headWHEN THUNDER ROLLS in from dark clouds hanging menacingly over the Sand Hills and nervous lightning flashes across the sky, folks in Hay Springs dash for cover and nervously wait for the worst.

"Are the beeves secure?" they ask their burliest hands. "Are all the doors bolted?" "Have you seen it yet?"

These are brave people, but on nights like this, with the thunder and lightning making a holocaust of the sky, stark memories of the past return. They

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

watch for rolling green mist, for huge eyes spitting lightning, and listen to the thunder.

watch for rolling green mist, for huge eyes spitting lightning, and listen to the thunder.

For this is the country of Giganticus Bruiervious, the most horrible apparition yet seen by honest men. His lair is Walgren Lake. From it, he roams across the land trying to satisfy his enormous appetite. His steps are slow but thunderous, and when he wags his powerful tail, the ground shakes so hard Sand Hillers become seasick.

Fortunately, Giganticus hasn't made an appearance of late, but that doesn't mean that he won't roam roughshod over the country again. As late as 1923, Giganticus was still going strong. That year a picture of him appeared in the London Times with the following caption:

"By far the most vivid picture of the actions and features of a medieval monster which for three years has been terrifying the natives of the vicinity of Alkali (Walgren) Lake near the small town of Hay Springs, Nebraska, U.S.A., was received from our Omaha correspondent today."

When Giganticus was first heard of in 1885 or so, there were only a few scattered settlers in the area. Maybe Giganticus had been quietly resting here for centuries. No one knows, for until 1885, there were no people to tell about him. But when they did come, Giganticus was waiting to roar his greeting.

This was his country. And he didn't like the intrusion. One thing Giganticus (continued on page 24)

PHEASANTS in the Snow

by John KurtzTHE BIG RINGNECK broke out of the plum-brush thicket 100 yards ahead and high-tailed it into a snow-covered stand of sweet clover in a desperate attempt to escape his pursuer. Gene Hornbeck, my hunting partner, was hot on his trail, playing the bishop in his own brand of chess game and ready to trap the gaudy king at the end of the narrowing field.

In chess you must force the king into a spot where he can't move. The same is true in pheasant hunting, at least that's the pet theory that Gene and I were testing. We had four roosters by mid-morning.

The king played a tricky game but wind and weather were our pawns for checkmateSnow was riding a strong northwest wind as Gene zigzagged through the small stand. The king had only 50 yards before he ran out of cover. He, like the rest, was sticking close to the ground. Birds almost refused to fly, and as far as Gene and I were concerned, the frigid 20 degree mid-November temperatures were perfect for gunning.

The rooster legged it into the fence row that stretched from the field into bare pasture and Gene moved in to flush him.

"Checkmate," I heard him chuckle, as the bird slammed into the wind with the usual nerve-shattering cackle. The gun moved into action, swung smoothly with the flight, and the No. 4's connected in a flurry of feathers.

Gene took the fence in stride, retrieved his bird, and came grinning happily back to join me.

"I never thought I would get that rooster to fly," he said. "I saw him running ahead of us all the way down through that plum brush. He beelined it right through the sweet clover and up the fence row. I knew that bird was there, but if it hadn't been for the tracks, I might have passed him up."

"Let's get the car and check on this section to the north," I suggested. "There's bound to be plenty of birds there."

Hiking back to the car brought about an awareness of the weather as we faced into the pelting snow. I noticed a faint outline of trees to the north that would be Whitney. Off to the southeast the buttes of the Pine Ridge rose indistinctly into the snow-swept skies. But Gene and I were enjoying ourselves. We had taken time off from our Game Commission duties, he as photographer and I as park superintendent at Fort Robinson State Park, and were doing all right. We only hoped our luck would hold.

A knowledge of the ringneck's habits is the biggest factor in hunting success. One learns something new every season. Each change of weather and the progressive harvest of crops have a big influence on how the birds react and where they can be located.

The hunter should take advantage of every element. Wind can help him by concealing his approach when walking upwind. Gene had tested this point on the first birds of the day. We had decided to try a big plum-brush thicket bordering an irrigation ditch. The upwind side of the patch was pasture while soil-bank land bordered the other sides. Gene decided to approach from downwind, I would circle and come in on the pasture side as a blocker.

My partner walked in on the patch cautiously, stepped over the irrigation ditch, and looked down on 15 or 20 birds within 20 feet of him. They were

8

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

taken completely by surprise. The pheasants were reluctant to fly in the high wind and scattered like a bunch of bunnies.

taken completely by surprise. The pheasants were reluctant to fly in the high wind and scattered like a bunch of bunnies.

One came out into the pasture in front of me. When he discovered that he was cornered, he climbed the sky. I bagged him on the second shot. Gene quickly moved along the edge of the thicket and finally succeeded in putting two roosters in the air, bagging one in three tries.

We were able to flush only about half of the birds Gene had seen. They had slipped back into the weed patch and played hide-and-seek with us. Even Chief, my young springer, couldn't force them to take wing. We knew the birds were still in the patch from the tracks in the snow, but finally gave up trying.

Arriving at the section, we first got permission from the landowner, then scanned the area to plan our tactics. The section was interspersed with farm and pasture land. We decided on the small weed patches to the north and a small creek bottom well grown with grass.

Snow was beginning to drift into the upwind sides of the ditches and stubble fields, offering little shelter for the birds. Once Gene and I had hiked through a "forty" of picked corn, we hit an irrigation ditch that was covered with a good stand of sunflowers and sweet clover along the banks.

Fairly fresh tracks headed down the ditch. At least six or eight birds were somewhere ahead. Gene volunteered to swing out wide in the field and cut in a quarter-mile upwind on the ditch. Chief and I would push the strip of cover toward him.

The young springer was on his third pheasant hunt and had a lot of interest in the fresh tracks that soon began showing in the snow of the ditch. Suddenly, he took off at express-train speed, hot behind a running rooster. The command, "Whoa," fell on unhearing ears, as the young dog put the bird in the air out of range.

The other pheasants hadn't taken to the sky and were moving ahead of me in the thick cover of the weeds. I wasn't too perturbed. A young dog must learn to hunt and obey commands, but he must also have a chance to follow his nose once in awhile. Actually, the dog's burst down the ditch helped by confusing the ringnecks.

Chief swung back into the cover and, lured by the fresh scent of the birds, nosed through the weed patch thoroughly. I talked to him occasionally and he worked close enough so that I could score.

The distance began to shorten between Gene and me. When it dropped to 100 yards, I let the dog move out on his own. A couple of hens were the first to break. They were crouched on the lee side of the ditch and got air-borne just scant inches in front of the eager dog. I could see Gene working back and forth at the end, now only 75 yards away. The birds were once again at "check". A rooster erupted almost under Gene's nose, and the lanky hunter dropped him at about 30 yards.

His shot started a chain reaction. Cackling roosters exploded everywhere. I caught a glimpse of one getting up on the downwind side of the ditch. Following him with the gun was impossible through the dense cover. Jumping the ditch, I broke out just in time to catch a second trying the same trick. He had the tail wind with him and was moving like a feathered jet. I swung the barrel in front, picked up my lead, allowed an extra two feet, just in case, and sent a load of No. 5's booming out of my three-inch Magnum. The charge caught him broadside at 50 yards, and he cartwheeled end over end across the rows of corn stubble.

Gene's gun was booming on the other side of the weed patch as I saw two roosters swing into the wind. One wobbled unsteadily. The winged bird climbed high, then slipped (continued on page 25)

JANUARY, 1962 9

The RIO GRANDE

Future turkey-hunting prospects look bright as new breed takes up housekeeping in Sand HillsWHIRRING TO ESCAPE the shipping crate as its door is swung open, the gobbler wings over the slight rise and eases into the isolated creek bed. Eyeing a grassy clearing, he glides into the open spot to claim his new home in west-central Nebraska.

Hitting the ground on the dead run, he scurries into the cottonwood saplings to hide, recover his breath, and take notice of his new surroundings. More of his Rio Grande cohorts float momentarily through the air before dropping into the foliage. Then all is quiet as the crisp, fall wind whispers through tall cottonwoods. The long journey from the southwest was over.

The turkey's new home is similar to the terrain where the birds were captured in the wild. Stream breaks and rolling range lands should have all the 22 new emigrants need to live and prosper. Plenty of surface water is available in the creek. Food in a variety of fruits, grass and weed seeds, insects, and cultivated grain is plentiful. The cottonwoods along the creek will serve as primary roosting trees. And

JANUARY, 1962

the open range land provides adequate vision for the birds to escape from predators.

the open range land provides adequate vision for the birds to escape from predators.

Perhaps the most important attraction of this west-central introduction site is the isolation from man and his domestic turkeys. Artificial feeding near farmsteads and the almost inevitable interbreeding with farm turkeys is the most destructive fate that can befall these prized game birds.

These assets—open range land, isolation, water, food, cover, and roosting sites—are present in the 25 Rio Grande release areas in central, southwest, and northeast Nebraska. Since November, groups of 10 to 30 birds have been freed at each release site.

Unlike the eastern variety, the Rio Grande is a tall, rangy bird. His long legs are especially adapted to carry him over a vast area each day. He is extremely alert to danger, thus assuring survival from natural predators. He's the kind of game bird that will test the skill of the most experienced shot.

In comparison to the Merriam's turkey, now well established in parts of the Pine Ridge, the Rio Grande has tail feathers tipped with brown. He also sports a bluish-black feathering on his lower back. The Merriam's variety has distinct white tips on the tail feathers and a white mottled rump.

Trial plantings of Rio Grande turkeys were made late last spring in the Benkelman and Sargent areas. Since the birds were released during the latter part of the breeding season, technicians did not expect any reproduction the first year. The birds obviously adapted easily to Nebraska and surprised observers with several broods of young.

This early success may indicate the addition of another major species to the ranks of established game birds here. If they do take hold, hunters can be sure of tracking a most worthy adversary. They'll be matching wits with the wariest of the gobbler clan—the Rio Grande turkey.

THE END

BROWNVILLE, USA

by Jane Smith The town the 20th century passed by lives again, remembering the days when river boats linked the east with the untamed frontierON THE OLD Missouri, snuggled in the protecting lap of the rolling river bluffs, a sleepy old Nebraska village is once more stretching to life. Brownville, like the legendary Rip Van Winkle, has awakened from a lengthy hibernation, its enchanting river-boat aura still intact. Uniquely, the 20th century has passed it by, and the town which figured so prominently in frontier Nebraska stands as it did 100 years ago, ready to be inspected.

13

Great things were predicted by the early city fathers. It's no wonder. Wagon trains stocked up

here before heading toward the setting sun. Resplendent paddle wheelers made Brownville their port

of call, bringing music and laughter and goods to the frontier. Dignitaries bustled back and forth

between Brownville and Omaha, Brownville and

14

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Washington, Brownville and the world. This would

be the site of a new state capitol, the natural setting for a medical college. While the rest of

Nebraska was comfortable in homespuns and a diet of beans dished up on a tin plate, Brownville

preferred silks and satins and meals served up on the finest silver.

Washington, Brownville and the world. This would

be the site of a new state capitol, the natural setting for a medical college. While the rest of

Nebraska was comfortable in homespuns and a diet of beans dished up on a tin plate, Brownville

preferred silks and satins and meals served up on the finest silver.

But the tides of fortune changed. The railroad went to Omaha, the county seat to Auburn, the capitol to Lincoln, and Brownville went into hibernation. Today Brownville lives again, not because of commerce or industry or government, but because people want to rub shoulders with yesteryear. Last year nearly 30,000 people did just that at the "City of Seven Hills".

What attracts people to Brownville? Much of the answer lies with the town itself. No neon lights or movie marquees mar the quaint beauty of Main Street. Here and there, behind Victorian houses, are barns where the family cow was once and may still be kept. Many families still draw water from "wishing" wells, using timeworn oaken buckets. Towering oaks and maples shelter historic sites and memories of events and people long gone. An aura of peaceful-ness and an echo of the leisurely life of another century captivate visitors who tarry to sample the old town's magic.

Visitors entering Brownville from the Missouri River bridge approach are greeted by a gaily painted

JANUARY, 1962

15

sign welcoming them to "Historic Brownville, where Nebraska begins". These pink signs are used throughout the village to mark sites of interest. The lettering they carry is a direct reproduction of that found on an original city plaque.

sign welcoming them to "Historic Brownville, where Nebraska begins". These pink signs are used throughout the village to mark sites of interest. The lettering they carry is a direct reproduction of that found on an original city plaque.

From the bridge, the visitor's eye is caught by fishing shanties along the river. Here fishermen ply their trade just as their fathers and grandfathers before them did, rising at dawn to skim over the river in flat-bottom "jo" boats and returning to process their catch of carp and catfish.

During Brownville's beginning in the 1850's, the river front was the scene of bustling activity. Thousands of emigrants disembarked at the old steam

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

wharf on their way to the Colorado gold fields or homes in the west. Ox teams and mule trains strained up the hill from the river, the beginning of the long journey into the frontier. Hikers tramping through the wooded bluffs occasionally still find ox shoes from the trains which passed this way.

wharf on their way to the Colorado gold fields or homes in the west. Ox teams and mule trains strained up the hill from the river, the beginning of the long journey into the frontier. Hikers tramping through the wooded bluffs occasionally still find ox shoes from the trains which passed this way.

Here, too, cattlemen forded the river with great herds of Texas longhorns. The bawling, wild-eyed beasts were forced to swim the river to Missouri where they continued on the last stretch of the famed Texas trail.

Today, the river front is once more the scene of varied activities. Tow boats and barges loaded with grain and other commodities churn past Brownville several times each day, occasionally stopping to unload or pick up barges. Crews from the Corps of Engineers work from dawn to dusk, strengthening the shore line with dikes and bordering bands of rock "riprap" to keep the old Missouri within its banks and the channel open for navigation. Water skiing, boating, and fishing are popular river sports.

Advancing up Main Street from the river front, the visitor sees the old Lone Tree Saloon. Jesse James is said to have played poker here when he was in town. In later years, the Lone Tree was often raided by John Law, and more than one two-fisted hombre was hauled off to the calaboose. Willa Cather often wrote of such doings in her popular books.

Across the street is the site of the old land office where Daniel Freeman signed for the first official homestead in the nation. Freeman, a Union soldier, was in town to celebrate New Year's Eve. Knowing that he had to be on his way before the land office officially opened for the first homestead filings the next morning, the agent let Freeman sign the historic claim shortly after midnight. The land-office site has now been purchased by the Brownville Historical Society and present plans call for the erection of a replica of the building in time for the national centennial of the Homestead Act this year.

In this same tract of land is the location of the first telegraph office in Nebraska, the old Hoadley Hotel. The foundations and part of the structure are still standing, and work has begun to restore at least part of the building.

One of the first messages to hum over the telegraph wires was from pioneer politician R. W. Furnas and read:

"The Advertiser sends greetings. Give us your hand. Hot as blazes; thermometer 104°F in the shade. What's the news?"

In the first telegram ever to be received in Nebraska, the St. Joseph, Missouri, editor replied:

"We are most happy to return your greeting. Thermometer at 100°F, and rising like h—1. You ask for the news: Douglas stock fully up to the thermometer, and rising as rapidly. St. Joe drinks Nebraska's health."

As the visitor progresses down Main Street, he notices the old brick houses of the river-boat era. One of these is the Carson house. The original brick portion of the house was built by the founder of Brownville, Richard Brown. It was later purchased by

JANUARY, 1962

17

pioneer banker John L. Carson and enlarged to its present dimensions. The house, with its original Victorian furnishings, was opened to the public in 1958 by the present owner, Miss Rose Carson of Lincoln. Since then thousands have admired the handsome period furnishings. The back gardens of the grounds have been freshly landscaped to add to the attractiveness of the mansion and carriage house.

pioneer banker John L. Carson and enlarged to its present dimensions. The house, with its original Victorian furnishings, was opened to the public in 1958 by the present owner, Miss Rose Carson of Lincoln. Since then thousands have admired the handsome period furnishings. The back gardens of the grounds have been freshly landscaped to add to the attractiveness of the mansion and carriage house.

On down the street stands the Captain Bailey house, now used by the Brownville Historical Society as a museum. Filled with memory-provoking items from the past, the museum is open daily from May through October, as are other Brownville attractions.

At the end of Main Street is the old brewery cave. This cave has recently been purchased and along with a "mystery house" has been opened to the public. Built in 1866, the half-block-long bricked cave served as a storehouse for beer from the old brewery. Some 3,000 barrels a year were made— and nearly all of it was consumed by local villagers.

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

The brewery's original machinery is now buried near the cave, and the present owners plan to excavate it and set it up for inspection.

The brewery's original machinery is now buried near the cave, and the present owners plan to excavate it and set it up for inspection.

Visitors can find many more interesting attractions off of Main Street. By following Cock Robin Hollow and turning left at the fork in the road, one finds himself in the old Walnut Grove Cemetery. Situated high on a Missouri River bluff, the cemetery is sheltered by murmuring pines. Many of the tombstones in this peaceful spot date to the 1850's.

The stately Muir house stands just a block from Main on First Street. This residence, like the rest of those built during the period, was made of brick manufactured from native clay in the Brownville brick factory. The T. W. Tipton house at the top of Fourth Street, the Minick house, and the Governor Furnas house are other examples of "steamboat" architecture.

Two of the churches from old Brownville are still standing and in use. The Christian Church on Main

JANUARY, 1962

19

Street was rebuilt in 1903 following a fire which destroyed the original building. The Methodist Church building is the oldest in continuous use in the state. This building was used briefly as the Brownville Medical College, but was sold to the Methodists in 1861. Both churches are open to visitors.

Street was rebuilt in 1903 following a fire which destroyed the original building. The Methodist Church building is the oldest in continuous use in the state. This building was used briefly as the Brownville Medical College, but was sold to the Methodists in 1861. Both churches are open to visitors.

In addition to the attractions which are open daily, the Historical Society stages two festivals which draw nearly 10,000 visitors annually. Included in the day's activities may be such attractions as a tour of old homes, a ski show on the river, or a period style show.

An Old-Time Fiddlers Contest attracts nearly 60 contestants and hundreds of spectators. The "Flea Market" is also an annual attraction at spring festivals. Antique dealers from Nebraska and several surrounding states bring their wares to Brownville and set up street stands to display and sell their goods. Other activities on the streets include spinning on an old-fashioned spinning wheel, rug weaving, candle making, and other crafts. Horses and buggies traverse Main Street, giving carriage rides to delighted youngsters and many of their parents.

Brownville has much to offer those who are not history buffs. Many visit the town simply to view the spectacular scenery. Others come in the fall for the excellent duck and goose hunting. Both blinds and experienced guides are available. Pheasants, quail, rabbits, and squirrels abound in the bluffs. The Missouri bottom land also furnishes excellent shooting for deer hunters.

Boating enthusiasts arrive in numbers during the summer months to launch their craft on the Missouri River. Previously maintained by a local boat club, the docks and launching area are now part of the Game Commission's new recreation area.

Much of the credit for the town's revival must go to the Brownville Historical Society and one of its founders, Nebraska's famed artist Terence Duren of Shelby. This group, organized in 1955, now has over 500 members. They have been responsible for marking many of the old buildings and sites and preserving others for future generations.

Thanks to the villagers and the thousands of visitors who have "discovered" the town that the 20th century passed by, Brownville lives again. Visit it soon. THE END

20 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

DO-IT-YOURSELF TIP UP

Here's low-priced answer to successful ice anglingSimple construction makes this a natural for a bad-weather week end. Start by making a spool (1) from masonite circles 23A inches in diameter, fastened with small nails to each end of a 1-inch length of dowel.

Cut a slot in the main beam with a coping saw (2) after drilling holes. A nail with the head removed (3) will hold the line while rig is set. Screw eye is only a line guide.

Fasten both wheels on the cross beam (4) with %-inch screws, using washers inside to insure easy turning. The slip-slot on the main beam (5) should be off-center and about 5 inches long.

All materials needed for one tip up (6) will cost about 25 £ if bought at the store. Wood and some hardware can probably be found around the house to reduce the cost even more.

When completed (7 and 8), tension on spring holds cross beam but allows for sliding adjustment to counterbalance the weight and line under the ice. Spool should turn freely so fish can't feel resistance on the line.

Set rig has the line looped around the headless nail. When fish strikes, the main beam is pulled down into spudded hole, the line slips off the nail, and the flag alerts the angler.

FOR THE BIRDS

by Bill Bailey Game Division Project LeaderSNOW SWIRLED in the streets of the small town. Drifts had already appeared on the lee side of the parked cars, and the temperature had dropped sharply within the hour. The men in the corner grill and pool room were keeping close tabs on the storm, remembering the 1959-60 winter when a long seige of snow made the going tough for men and animals alike.

That year these men were concerned about the wildlife that abounded on their farms. Many had gone to the extra effort and expense of getting grain to the pheasants and quail that seemed so helpless under the constant pounding of the storm. Farmers and sportsmen throughout the state had followed this same pattern, backing up their genuine concern with an active program.

Those in the cozy confines of the building couldn't help but wonder whether this storm might produce the same hardships on wildlife. Should the birds be fed as had been done two years ago?

If the severe winter did nothing else, it did provide all concerned with a better knowledge of the capabilities of wildlife under adverse conditions and feeding programs in general. Although Nebraskans made commendable efforts at winter feeding, the program had little effect on either pheasant or quail populations. It would have been impossible for the Nebraska Game Commission to have fed enough to economically and physically alter the course of events.

On limited areas, the efforts of sportsmen and farmers may have saved a few birds, but considering the state-wide population, feeding did little to change the over-all picture. Many sportsmen in quail range found that their hastily established feeding stations were never used. Others observed that concentrations of birds at the same site each day tended to concentrate predators quick to take advantage of an easy meal. Often, mortality was just as great in areas receiving the emergency rations as non-feed areas.

These programs and efforts did serve some purpose, however. The farmers and sportsmen were united in a common cause, and attention was focused

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

on a basic problem—habitat requirements of both pheasants and quail. Birds need cover near food sources which is capable of providing necessary shelter during severe weather. Without it, emergency feeding cannot alter the amount of mortality.

on a basic problem—habitat requirements of both pheasants and quail. Birds need cover near food sources which is capable of providing necessary shelter during severe weather. Without it, emergency feeding cannot alter the amount of mortality.

What were the effects on pheasant and quail populations?

Bobwhite were at an all-time high in 1958 and 1959. Many coveys occurred in marginal quail coverts and could not be expected to survive severe weather. These birds were highly vulnerable and, as could be expected, the majority were lost. No amount of emergency feeding would have saved them since the basic problem was one of adequate cover, not food. Quail were lost in some of the better coverts, too, but here the losses were not so severe.

Quail were not wiped out over large areas of their range, as many suspected would happen, although numbers were drastically reduced. The 1960 hunting season was slim but it was evident that the population was recovering rapidly. Surveys in 1961 showed populations were slightly above the 14-year average and hunting success was good in many areas. The recovery had been amazing, illustrating the terrific reproduction potential of bobwhite when reduced below the carrying capacity of their range.

Pheasant populations almost equalled those of 1959. By the fall of 1961, populations had increased and exceeded those of 1959, and equalled or exceeded those of 1958. Again, a well-balanced habitat was the key factor. Areas having adequate cover fared much better than those deficient in cover.

The ringneck is an extremely hardy bird, one that is adapted to the climatic extremes of its range. He has not achieved these adaptations through year-to-year handouts but rather through hundreds of years of evolution on the wind-swept plains of its native Asia and, later, under the adverse conditions existing in its adopted range of North America.

The ringneck will suffer some mortality during severe blizzards, but most of this is not due to starvation. In most cases, death can be attributed to suffocation or freezing. This is true if heavy winter cover is lacking or if they have to move considerable distance from cover to obtain food. Ice may freeze over the nostrils, producing suffocation, particularly if birds have to forage over wide areas with little or no cover. Or some may be trapped beneath drifts, eventually succumbing to starvation or predators. Quail may suffer mortality of this type, too. Winter feeding will not prevent these losses. But good winter cover near permanent food sources will hold losses to a minimum.

If there are severe storms this winter, groups with well-meant intentions may again advocate emergency feeding programs. They may devote time, energy, and money to help carry it out. But there are alternate programs which can be completed far in advance of an emergency—programs that will yield greater dividends over a longer period of time for the money spent. No amount of emergency feeding will substitute for a well-balanced habitat. In such areas emergency feeding will be unnecessary. This is the area in which all concerned should devote money and energy. The benefits will be far more permanent.

Should individuals or groups care to feed during severe weather, several things should be remembered. Establish the feed stations in good cover. Do not feed in open areas away from cover where the birds will be easy prey for predators. Do not feed along well-used highways. You may do more harm than good. Do not scatter feed promiscuously.

Feed only in covey areas used by the birds. During severe weather, quail will not move great distances. Your efforts may be wasted unless you establish the station close to the covey. Feed constantly, once you have started. Efforts are wasted if only a meal is provided. Also, you may create a situation in which the birds are dependent on your handouts. Since you may be responsible for their dependency, don't let them down.

Remember, emergency winter-feeding crash pro grams are not the ultimate solution. They cannot replace a well-balanced habitat.

THE END JANUARY, 1962 23

MONSTER OF WALGREN LAKE

(continued jrom page 7)did like, and that was eating. Some folks say that once he got so hungry he swallowed a small island in the middle of the lake. His favorite meal is a dozen young calves topped off with a fieldful of hay.

That Giganticus existed cannot be doubted. There is hardly a fisherman in northwestern Nebraska who will not vouch for the fact, and everyone knows you can always believe a fisherman.

Until the day he died one early-day angler told his tale of seeing Giganticus. While out fishing in Walgren one day, a terrible tempest came over the lake. It then covered about 120 acres. The terrified fisherman tried to reach shore but a combination of tornado and typhoon roared over the water.

More than once he thought he was finished. Just as his small craft plunged over the crest of a wave, he happened to glance down through the water and saw a mountainous peak. It was Giganticus, snoozing. Satan's own had twitched his giant ear and the whole lake became a roaring tempest. Finally, after a day or so, the fisherman fought his way to shore.

Giganticus did sleep a lot, sometimes as long as for a year or so. Then fully rested, he would come out of the lake and prowl around looking for all the trouble he could get into. When after a long period of hibernation Giganticus decided to surface, it was usually unsuspecting tourists who fared the worst.

One group of eastern innocents was traveling south out of Hay Springs when, without any cause,the clear sky clouded over and the heavens rumbled. Before the travelers knew it, they were surrounded with a mist so thick they couldn't see where they were going. They decided the best thing to do would be get back to Hay Springs. But the mist began to get green and the earth was rolling beneath them and their car was bouncing along at a terrible speed. When they finally escaped the horrible shroud, the dudes discovered that they had been bounced all the way to Valentine. Of course, this might have been exaggerated. They probably got to Gordon.

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS 10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 CUSTOM GUNSTOCK WORK. Rifle, shotgun, and pistol grips. Bill Edward, 2333 So. 61st, Lincoln. Ph. 489-3425. GUN CLUBS, Rifle Associations, Skeet Shoots. Present our award medals or ribbons. Fast service, low prices. HERFF JONES COMPANY 1109 South 36th, Omaha, Nebraska. Phone 342-2268. AKC BLACK LABRADORS. Bold, birdy, born retrievers. Easily trained, excellent pedigrees furnished, $50 up. Few young Brittanys, good prospects. Kewanee Retrievers, Phone 26W3, Valentine, Nebraska.When Hay Springs residents heard of this, they just shook their heads. Giganticus was on the loose again. Being of honest and friendly western stock, Hay Springers wished Giganticus would learn to leave the tourists alone. He would scare off business.

But they were wrong. As word of the monster spread around Nebraska—and the world—disbelievers flocked to the area so they could prove that Giganticus didn't exist.

Skeptics arrived by dozens, though few were brave enough to spend a night on the banks of Walgren Lake to see if they could spy the monster. Finally, an especially unbelieving gent from Omaha laughed at danger and set out one night to camp on the shores. The next morning, a babbling, white-haired wretch stumbled into town. It was the skeptic. The townspeople took care of the pitiful fellow. Three days and a few stiff belts later, he recovered his wits long enough to tell his story of horror.

The Omahan had just settled down for the night when a frightful roar filled the air. The clouds became thick, and the fateful mist began to roll in from the lake. The skeptic looked and there above the cover of the fog was the horrible head of Giganticus.

"The monster seemed to unfold out of the lake," he continued in his cracked, old-man's voice. "He was serpentine, somewhat similar to a dinosaur, with a head like an enormous oil barrel. From the tip of his nose to the tip of his tail, he was at least 300 feet long. And when he yawned, the opening of his mouth was big enough to hold a 10-story building."

As his fame spread around the world, Giganticus became a very vain monster. He made himself more terrible than ever, and the townspeople tried everything to get rid of him. But all attempts were futile.

Then, an especially intelligent native came up with the idea. If they just ignored Giganticus, maybe he would go away. Hay Springers followed the plan, and no matter what trick the monster tried, it didn't attract any attention. Either bored with life or disgusted that he couldn't create too much of a stir any more, Giganticus stopped making appearances.

Just what did happen to him isn't known. Some think he has gone into some subterranean retreat. Others think that perhaps he has deserted the lake altogether and is now residing in Scotland.

Today Walgren Lake is a state recreation area. People camp on the shores, children play in the playground, and folks picnic there. It's a pretty, tranquil area, always ready to supply plenty of family fun. Walgren's tree-shaded shores make the perfect place for fishermen to sit and cast in their lines for black

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

crappie, bullheads, sunfish, perch, and catfish.

crappie, bullheads, sunfish, perch, and catfish.

No wildlife as fearful as Giganticus is found around the lake any more. Walgren is now a game refuge with no hunting allowed at any time during the year. Nature lovers will delight in the thousands of ducks that stop in the fall while on their southern migration. In past years, there have been as many as 12,000 to 14,000 ducks on the area at one time.

Walgren Lake and its Giganticus have certainly reformed. It's such a nice place now that all the inhabitants of the region sincerely believe that green clouds and crashing ominous thunder will never be heard or seen again. Who knows?

THE ENDPHEASANTS IN THE SNOW

(continued from page 9)toward me with the wind. Chief, the young, ever-eager springer, saw the bird coming and high tailed it toward him. I threw a shot at the bird from about 60 yards in hopes of finishing what Gene had started but drew a blank. The rooster pitched into the cornfield about 300 yards away with Chief not far behind. The springer had never made a retrieve on a winged bird yet.

Chief put on an extra burst of speed and switched ends trying to catch the speedy old rooster. It was touch and go for a few seconds, but he won out and came trotting in, proudly holding the rooster.

"He's getting the hang of it," Gene said. "I saw that first rooster running down the ditch toward me, but just couldn't reach him when he got up."

"For a minute I was afraid he was going to bust them all," I added, "but then if he had, we would still be hunting now. The way I count it, we're filled."

Later that day Gene headed back to Lincoln and I got back to my duties at the park. But I have been out on a number of occasions since to test Gene's and my theories on hunting in the snow.

I have a definite pattern that is followed through the long season. Guns and loads are changed to handle the situations. At the beginning of the season, for instance, Gene shoots a little 20-gauge over-and-under, bored, improved, and modified, using high brass No. 7%'s. As the shooting gets tougher and the birds fewer, he switches to No. 4 Magnums in the 20-gauge. When the occasion warrants, he uses the same load in his modified 12-gauge. This is his favorite setup for blocking on drives where the shooting can be out to 50 or 55 yards.

My guns are both 12-gauges and I pretty much follow the same pattern, except that I can go Gene one better by taking my duck gun, a three-inch 12-gauge Magnum, for those long shots. I most often use No. 5 shot in the Magnum. With its full choke, I can throw a killing pattern out to 60 yards.

Just as in the game of chess, ringneck hunting requires skill. You must pit your knowledge against the bird's superior senses of hearing and sight. But you have reasoning. Use it for your checkmate on the king.

THE ENDSportsman's CHECK LIST

FISHING REGULATION CHANGESA change in the fishing regulations now requires that each angler must keep his catch on a separate stringer, or in a separate container, and under his control. Another states that the throat of a landing net must not exceed 24 inches in diameter, and may not have a handle over four feet in length.

Motorboating on Beaver State Lake in Cherry County—previously restricted to motors of six horsepower or less—is now allowed with a boat and motor of any size.

It is still illegal for any person to take minnows or bait for other than personal use for a distance of 200 yards below any dam or other artificial stream obstruction. Other parts of the law have been amended to allow anglers to seine for bait and minnows for their own personal use in these areas, provided the net is a legal minnow seine.

Many streams throughout the state were previously closed to the taking of any bait or minnows for any purpose. This regulation now prohibits the snagging of fish in these protected waters. Snagging and seining activities are not permitted. See the "1962 Guide to NEBRASKAland Fishing" for full particulars.

GAME STORAGE LIMITATIONSHunters with game in the freezer or in cold storage should remember that state regulations stipulate game may not be kept for a period longer than 90 days following the close of the season for that species. The only exception is that deer and antelope meat may be kept until the last day of December of the year following the date it was taken.

Game may not be kept after the following dates: prairie grouse, January 27; Wilson's snipe, February 3; gallinules and rails, February 23; geese, February 27; ducks, mergansers, and coots, March 6; quail, March 17; pheasants, April 14; and squirrels, April 15.

Game generally has the best flavor if cooked only a few weeks after freezing.

1962 BOAT REGISTRATIONThe annual boat registration process has been somewhat simplified. Certification by the county tax assessor and treasurer is now made on the application blank instead of on a separate form.

Owners of boats presently registered in Nebraska will soon receive by mail a copy of the up-to-date boating regulations and a 1962 application. New boat owners should obtain an official application from their county tax assessor and fill in all the required information.

The completed application form should then be taken to the county tax assessor and treasurer for their certification. This process can only be handled by the officials in the county in which the boat owner resides.

After all information has been given and the certification is completed, the official form and the proper registration fee—according to the craft's classification—must be mailed to: Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln 9, Nebraska.

Although boat owners have until April 1 to have their craft re-registered, they should send in their application to avoid the last-minute rush.

THE END JANUARY, 1962 25

notes on Nebraska fauna...

SACRAMENTO PERCH

VERY RECENTLY, a new member of the sun-fish family was introduced into Nebraska waters. This fish, called Sacramento perch, Archoplites interrupius, does not look like the common yellow perch found here. Instead the new species resembles the rock bass in physical appearance.

The name, Sacramento, comes from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River system in California where this perch was first found. The fish's color is uniformly black or brassy, and displays several irregular vertical bars with a blotch spot on the gill cover. Unlike other Nebraska species, the Sacramento's tail is short and stubby. The mouth closely resembles that of the crappie.

This fish was originally the only member of the sunfish family to be found west of the Rocky Mountains. Today, it is common only in the alkaline lakes of western Nevada and a few lakes in California.

That the Sacramento perch occurs in the alkaline mineral waters of Nevada was the prime reason for experimental releases in Nebraska's Sand Hills lakes. Since about 20 per cent of these lakes do not support native fish life because of high salt content, the Game Commission became interested in finding a

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

sport fish which could survive under such chemical conditions. After considerable research, the Sacramento perch was selected as having the best potential. First releases were made in the fall of 1961, in select lakes having salt content similar to those in Nevada.

sport fish which could survive under such chemical conditions. After considerable research, the Sacramento perch was selected as having the best potential. First releases were made in the fall of 1961, in select lakes having salt content similar to those in Nevada.

What can the angler expect if this species takes hold here? The perch should grow to moderate size— perhaps up to 15 inches and 4% pounds. The larger lakes will produce the largest fish, with growth depending upon food supply and the amount of salts in the water. Anyone who has eaten the Sacramento says that the meat is prime. In fact, many western anglers give him the nod over trout for having real table qualities.

Anglers should adopt some of the "percher" techniques used by Nevada and California fishermen in taking this species. Skill is required, since the perch is a light hitter. The hook must be set fast and sure. A variety of lures may be tried before the winning bait is found. Some of the best catches are made with spin-cast streamer flies that are weighted to bump along the lake bottom. Many fishermen rig their baits so that the weight is at the end of the line, with leader and lures about a foot above.

The Sacramento's habitat preferences appear to be quite broad, ranging from large, deep reservoirs and natural lakes to small impoundments and shallow, weedy lakes. Spawning takes place from late May and lasts through July, depending upon water temperatures. Spawning temperatures usually range between 75 and 80 degrees. Then the female spawns her eggs at random over submerged logs, aquatic plants, and rubble. Some nest building has been observed on gravel and sand bottoms. It appears that the species is suitably adapted to a wide range of natural spawning sites.

There will be no food problem here as the diet consists of small fish and water insects. A great variety of these are available in most lakes. Actually, many of the alkaline Sand Hills lakes support such a super market of fine fish foods that populations may reach numbers totalling 125 pounds per acre. Under such good growth conditions, the fish may be expected to reach 3V2 inches by the first year and attain catchable size by the third year at 7 to 9 inches.

Since very little has been written about this species, and since introductions were made only last fall, there's still much to learn about the perch's life history. At the moment, several questions have been posed regarding survival. One is whether the Sacramento will withstand the comparatively harsh winters of the Sand Hills country. Winterkill may become a very limiting condition for success of new fish plantings. Another far-reaching problem concerns the complex alkalinity of Sand Hills lakes. Continuing research should determine the most satisfactory salt level for the best living standards. Research of inland salt waters may eventually shed light on the multiple problems often faced when stocking new fish species in such lakes.

If all goes well, Sacramentos introduced in 1961 should survive in those lakes having moderate salt content and spawners held at the Valentine Hatchery should be successful. By 1963, the perch should be established in between 10 and 15 Sand Hills lakes, with some being creeled the following spring.

Don't anticipate an initial large-scale stocking program throughout the state. The species must first be tried in lakes that have water chemistry similar to that in Nevada. Furthermore, since little is known about the "living world" of the fish, all releases during the next few years must be considered experimental. It's doubtful that large-scale stocking will be made in farm ponds, gravel pits, and older reservoirs until research points the way to the actual need in these areas.

Again, the first consideration and interest is to find a game fish which will live and reproduce in the alkaline Sand Hills lakes, many of which now or never have supported fish populations. But this may not long be the case, thanks to the initial success of the Sacramento perch.

THE END JANUARY, 1962 27