OUTDOOR Nebraska

OCTOBER 1961 25 cents PIED PIPERS OF THE PLATTE Page 3 335 POUNDS OF CATFISH Page 3

OUTDOOR Nebraska

October 1961 Vol. 39, No. 10 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. Greg Smith, managing editor; C. G. "Bud" Pritchard, Wayne Dick H. Schaffer, Editor Tiller, Bob Waldrop

PIED PIPERS of the PLATTE

WE SAT BACK comfortably in the duck blind. It was colder than all get-out, but that's about par for November duck hunting in Nebraska. The decoys, set in a double-U pattern, bounced in the freezing Platte River as chunks of ice slipped by on their way to the Missouri, 16 miles away.

Ward Brunson of Louisville, my host and guide on this, my first try at Platte waterfowling, pointed southward. A goodly flock of mallards winged steadily upstream toward our blind.

"Travelers," Ward grunted.

He was right. The big birds had no intention of letting down. They were heading out to feed somewhere upstream. But plenty

OCTOBER, 1961

3

of their waterfowl brethren had stopped by this year. Ward and his partners had already bagged some 190 ducks and 9 geese from the blind. We hoped to add a few more to the record this morning.

of their waterfowl brethren had stopped by this year. Ward and his partners had already bagged some 190 ducks and 9 geese from the blind. We hoped to add a few more to the record this morning.

Ward and I hunched back in the confines of the blind again, straining our eyes for ducks that would be interested in our bouncing decoys. It was nice, real nice, to finally be doing something that resembled hunting for the first time since this "hunt" had started more than an hour ago.

It is not an easy thing even to get as far as I had. Before you can even think about hunting on the Platte, you have to line up a veteran who can get you there. Without him and his equipment, you might as well never start. You won't even get to the hunting waters.

Ward was such a veteran. A school teacher in his thirties, he took to the Platte everytime he had a free moment to follow his favorite sport. I had called him a couple of days earlier from Lincoln to line up the hunt.

"Pick you up at 5 o'clock," he said.

"But dawn isn't until . . ."

"Doesn't matter," he interrupted, "we'll have a lot to do before we can hunt."

This turned out to be somewhat of an understatement. I learned that the Platte hunter has what seems to be a good day's work to do before he can start shooting.

It begins after you've driven to the banks of the river. You stand there in the half-light, not feeling the bitter cold through layers of coats, chest waders, pants, insulated underwear, and whatever else you can put your hands on.

Pioneers described the Platte as the mile-wide-and-inch-deep river. They were wrong on both counts. The would-be duck hunter, unschooled in the shifting channels, could just about as easily drown as get to the blind.

Getting to the hunting is a problem in this section of the Platte, because most of the blinds are spotted on sand bars and islands close to the middle of the sprawling river. As I stood there in the brittle cold, I began to realize how different was this kind of waterfowling.

"There's our boat," said Ward, pointing to a flat-bottom chained to the shore.

"We ride?" I asked.

"We walk," he replied. "You just hang onto the boat in case you hit a hole."

Ward and I piled our gear into the boat and started on a predawn constitutional, waist deep in

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the frigid water. Ed's black retriever swam unconcernedly behind us.

the frigid water. Ed's black retriever swam unconcernedly behind us.

Several times I clung to the stern of the old boat as my feet lost the bottom. Chunks of ice bumped and floated by me. But I wasn't cold. This was heavy work. The cold was to come later. I was to get hotter before I got colder.

We chained the boat on the bank of an island about midstream. Loaded with equipment, I sweated as we trudged along a well-worn path through willows, high grass, and scrubby trees. The blind of native grasses sat on a bank overlooking a backwater in the island, an inviting spot for tired traveling ducks or freshly fed ones looking for a quiet spot to wash down a meal.

But there was no time to stand around admiring the water or the blind. There were decoys to be put out. We set up about 100 in a double-U pattern, one inside the other with the ends upstream. Finally, we crawled into the blind.

This is not wilderness hunting. The competition is tough. In all directions from our blind I could see other hunters preparing. And these are not only weekend hunters. In a blind like Brunson's, someone is there almost every morning. And they know their business. When the hunting is good they all get shots, but on slow days it's the guy with the most talent on the business end of a duck call who brings them in.

As soon as they appear the Pied Pipers of the Platte commence their wooing. In every blind one hunter croons on a duck call, while his partners check their guns and report progress.

Retrievers are an essential on the Platte. The swift-moving current quickly carries ducks downstream. Often a blind with three hunters counts two retrievers in the party, for the best bird dogs can get only three birds before the rest are lost.

Just as often the hunters charge out of their blinds on the heels of the retrievers, chasing ducks out across the shallow water, and hoping they don't hit a deep hole while they do it. Then it's back to the blind, warm your hands over a little oil stove, and get ready for the next flock. On the eastern Platte it may be mallards, pintails, teal, or bluebills.

These Platte River men put plenty of time and money into their sport. Duck hunters as a group are probably the most single-minded fanatics in the hunting fraternity. And the flat-water boys are possibly the most fanatical of the fanatics. Brunson and his partners have well over $2,000 invested in their setup. They figure $900 in decoys, $1,000 in dogs, and from $300 to $600 in boats. And, incidentally, they periodically use an airplane to inspect their spread from the ducks' viewpoint.

While most of the Platte hunters are just working blokes like the rest of us, some are able to adjust their hunting for some full days in the blind. They report that midday hunting is almost as good as anytime. Birds returning from feeding drop in for a drink and rest.

But even with all of our preparations and gear, Ward and I were skunked. Ducks continued to wing up the river but always too high. Neither the neat decoy pattern or Ward's tantalizing calls would bring them down. Ward was finally able to pick up an unsuspecting single so we didn't draw a goose egg. I never had a shot.

But I wasn't discouraged. Not on your life. Those big mallards flying over just out of range were too much of a come-on to keep me away from the blind. A group of us got a chance to use the spread a little later and really hit pay dirt.

There were lots of ducks. As we settled into our spots we talked with a hunter's happy nervousness about the flocks winging overhead. But those flocks weren't interested in us—not right then. For a moment, I thought we were going to get the same treatment that Ward and I had earlier. But only for a moment.

At first, we were happy to lure in an occasional single or double. We would crouch down as a single swooped cautiously near. The chortle of the duck call would urge him to us. While we all but held our breath he would make an inspection pass. And then, in most cases, he would swing back, set his wings, and start to settle among our decoys. A 12 gauge would echo up and down the Platte, then the retrieve, and then huddle down for the next loner.

Our limits were fast filling. I was plenty happy as things were. But then it began to rain ducks in flocks. They wTere back from eating and wanted water and rest. We would call one flock and be surprised by another, sneaking in low from another direction, determined to join our decoys.

Sometimes they were so plentiful we missed every blasted one of them. Other times two or three lay among our decoys when the rest whistled away. Long before quitting time we were finished. We could do nothing but sit back and admire our limits as thirsty ducks piled in among our decoys.

But no matter what time you hunt Nebraska's flat water, closing up shop is as strenuous as opening. There are the decoys to be brought in. Then, of course, there's always that walk and wade bit back to the main shore, usually happily hindered by the weight of fat mallards.

As you tie up the boat and stand there for a moment, looking back across Nebraska's mile-wide and inch-deep river, you have your own viewpoint. An inch deep? No. Your wet waders tell you that's not so. A mile wide? Your eyes tell you "no," but your tired bones and aching muscles say, "You bet your life, buddy. At least a mile wide, and probably more."

THE END

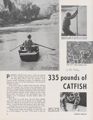

335 pounds of CATFISH

PUSHING AWAY from shore, I had the feeling we were checking traps instead of set lines in the Big Blue River. But my partner, Dick Franta, wasn't thinking of mink or muskrats as he labored on the oars of his flatbottom. He was after flathead catfish.

Dick had a right to think of the big ones. During July and August, the retired Crete policeman had creeled a whopping 335 pounds of catfish; 224 pounds in August alone. Before embarking, Dick had shown me his catfish calendar which backed up his claim. Each catch was noted on the appropriate day. His biggest was a 47-pound, 4-ounce lunker taken on August 23.

Now Dick is no fish hog. He just likes catfish. And what he can't eat, he passes on to friends. He takes his fishing as seriously as he once did police work. I could see that the minute I got in the boat.

Letting the river current do the work for a moment, Dick told me how he landed the big ones.

"Most people make the mistake of tying the line to a solid support," he said. "This gives a big cat

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

something to pull against. Nine times out of ten, he'll jerk the hook loose."

something to pull against. Nine times out of ten, he'll jerk the hook loose."

Dick's first set line was up ahead at a bend in the Blue. But I or anyone else couldn't see it. One end was attached to an underwater root, the other to a six-foot sappling rammed into the mud.

"This spot has been a real producer," he said. "The washing action of the river forms a deep hole here at the bend. Big cats in the neighborhood congregate in the hole during the day, then move out to feed along the shoulders of the channel at night."

Dick had set the main 175-pound-test line across the channel just above the hole. But the cats hadn't taken his bullhead offerings. After a final check, Dick headed the boat downstream to his next set.

"We're in luck," he said, "there's one on here and he feels like a big one." This was the crucial time, since the fish had more to pull against now than at any time since tasting that little bullhead.

It's no accident, regularly taking the Big Blue for 40-pounders. Here's an ex-cop with his cluesDick pulled steadily and there it was— an unmistakable catfish head that must have been at least six inches in width. Easing the boat closer by pulling on the main line, he reached out and jammed his gloved hand into the gaping mouth.

"This baby should weigh an easy 25 pounds," he said as he heaved it up and into the boat between us.

Running out the line, we found a 6-pounder to make a total of 31 pounds, 9 ounces of catfish for one day's haul. Not bad for an hour's work on the oars.

Pulling our way back to Dick's car, he summed up his philosophy of fishing for flatheads. Blood baits, magic potions, hearts from boar hogs, and special lines that continually pump blood over the bait are fine for some people, but Dick believes they scare more fish away than they catch. His idea is feed them what they want to eat— namely bullheads.

Roy Owens, conservation officer from Crete, was waiting at Dick's car.

"See you've run up the box score," he said. "That big one will go mighty nice with the one you've got iced down in the trunk."

The officer was referring to the 40-pound, 12-ounce monster Dick had taken last night. I had the two of them heft the pair up for pictures, and once the cats were iced, the three of us headed for town for lunch.

I had been under the impression that Dick was a set-line purist and was surprised when Roy mentioned some of the big cats my angling companion had taken with rod and reel.

Dick, not one to toot his own horn, admitted that he had taken some nice ones.

"A couple of years back I tied on to one weighing 47 pounds," he said. "Boy, did he give me a battle. I wasn't planning on anything that big. Landing him on light tackle was a real chore."

When angling, Dick wads a gob of five or six night crawlers on a No. 6/0 hook. His calendar tally sheet proved the bait's worth. On August 9, he had landed a 20-pounder with such a setup.

I couldn't help but notice a certain gleam in the elderly man's eye as he talked about his catches. He had the look of a man who had found the answer to a deep mystery. Ask other Crete fishermen who dangle hooks in the Blue or consult Dick Franta's calendar and you'll know he has found the answer to catching the big ones. That total of 335 pounds of catfish is no accident.

THE END OCTOBER, 1961 7

Cowboy's DOG

by Sven E. B. Jacobson When the chips were down, we called on the shepherd to help tame the FrontierWAS A beautiful Sunday morning in April 1901, when Gus Olson and I discovered Fanny. We had decided to take some time off from setting up a 1,000-acre grazing ranch for the Kent Cattle Company to explore Cottonwood Creek. Gus, my brother-in-law, was foreman of the Sand Hills spread; I was but a teen-age boy.

The valley was alive with the sounds of spring as we moved up the stream's course. Birds were singing and high overhead hawks and an occasional turkey buzzard winged by. Just then we heard a faint whimper from a large gooseberry bush nearby.

"It's a coyote whelp caught in the barbs," Gus said. "I'll put him out of his misery with my staff."

"Let me take a look first," I offered. "Maybe I can lift him out of his prison."

I crawled down a slight bank and moved in close to the bush for a look. Lo and behold, there was an injured little shepherd puppy. Gus and I untangled the dog gently and took her to the ranch house where we dressed her wounds. There were two especially large cuts on her fuzzy back. Right then we decided to keep her and nurse her back to health. We named her Fanny. Little did we realize then that the dog we saved would in return save many lives and give back a life of unbounded usefulness.

Gus and I couldn't figure how the pup had got tangled up in the bush. Our only neighbor, three miles away, said they didn't know of shepherd dogs except for some seven miles away. Then we remembered the turkey buzzards and surmised that the deep back wounds were from a buzzard's talons. Fanny must have wiggled herself loose.

The pup grew rapidly and showed marked intelligence and attentiveness. We had to haul lumber some 10 miles from the nearest railroad station at Palmer for the ranch buildings. Each night Gus and I would get home late, but Fanny would be waiting at the gate.

Soon the ranch house was sufficiently completed so that Gus could bring my sister, Mary, and their three-year-old son, Vernie, to live with us. Mary was busy from the start, especially at the end of the long day when all of the hired men had to be fed and the chores done. It was after one of these long days when supper was over and it was becoming dusk that little Vernie could not be found around the ranch. All of the hands turned out to search every nook and corner, but to no avail. As it grew dark, we really began to be scared. There were hundreds of roving coyotes and a few bobcats in the area around the ranch.

After coming back from a careful but fruitless search along the creek, we took counsel. Just then I thought of Fanny and asked if anyone had seen her. Gus had a shrill whistle that he used in calling her. After the second or third try, we heard a faint bark from the darkness. Gus whistled again and again. After each whistle we heard the returning bark. It led us up a canyon that branched from the creek.

We covered more than a mile before we spotted the dog. I'll never forget that scene. There was Fanny, ready to take on anyone or anything that would harm the small boy leaning against her haunches. Evidently she had seen Vernie walking away from the ranch house and felt it her duty to go along and guard him. She had refused to leave the boy even with her master's repeated whistles and calls.

I could do a better job of rounding up cattle with Fanny than I could with (continued on page 24)

OCTOBER, 1961 9

the APPLE BIT

Why blame snakes. It was Eve who goofed at Garden of EdenEVER SINCE THE apple bit in the Garden of Eden, snakes have been the scorn of humanity. This is unfortunate. People forget the snakes' assets and remember only the danger of a few poisonous individuals.

Most important in favor of snakes is their usually unsung rodent-control powers. Of the 25 varieties found in Nebraska, 11 feed primarily on rats and mice. If there were no snakes, these rodents would damage thousands upon thousands of dollars worth of crops. Many landowners utilize these silent mousetraps by capturing them — usually bullsnakes — in fields and releasing the harmless reptiles in barns and farmyards. Also, water varieties are credited with helping to control overpopulations of frogs and fish.

Only four of the state's snake species are poisonous. The timber rattler in the southeast corner of the state is the only type that grows large enough to be a real threat to the average healthy adult Nebraskan. The copperhead, prairie rattler, and massasauga are not ordinarily large enough to inflict a death-dealing wound through even the simplest protective clothing.

Deaths attributed to snake bite in Nebraska are practically nonexistant, with the last authenticated

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

incident occurring in 1951. This contradicts the many stories of deaths that are circulated every summer.

incident occurring in 1951. This contradicts the many stories of deaths that are circulated every summer.

Some 22 varieties show a preference for the warmer climates and lower elevations of the southeastern part of the state. Nine are common only to this area, including the timber rattler, massasauga, and copperhead. Of the 25 found in the state, 11 types are in the northeast, 9 in the southwest, and only 6 in the northwest corner of the state.

The next time a snake crosses your path, con sider his economic value before clobbering him with a hoe. Learn to identify the snakes in your area, try to tolerate the harmless ones, and avoid the poisonous varieties. They all play an important role in the balance of nature.

THE END

LIVING COLOR

by Fred VicentMOST FISHERMEN have noticed different coloring among fish of the same species. Spawning male cutthroat trout taken from Strawberry Reservoir are usually brilliantly colored all the way up to their bright red gill covers while the female, although colored, is more drab in appearance. This coloration undoubtedly has a function in the reproductive cycle.

In some of the warmer ocean waters, groups of very poisonous fishes are found. Eating one of these fish would bring death in a few hours. Most of these poisonous species are brightly colored. Evidently these lethal fish have developed their color schemes to warn away other fish. To be mistaken for a more desirable morsel would be disastrous for both prey and predator.

Color adaptation to habitat is quite common both above and below the surface of the water. Some fish develop obliterative shading, shading that blends in with the surrounding area. This usually occurs in open water. However, the carp and some of the other fishes found in Utah rivers exhibit a gradation of shades from silvery or yellowish-white on the belly to a dark blue-green or brown on the back. Seen

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

from the surface against a background of water and stream bottom they have the appearance of being perfectly flat. Fish with patterns like this are almost indistinguishable at even a short distance.

from the surface against a background of water and stream bottom they have the appearance of being perfectly flat. Fish with patterns like this are almost indistinguishable at even a short distance.

Pacific salmon in the open ocean and members of the trout family in large open bodies of water are quite dark on top. This helps to protect them from predatory birds, while their silvery undersides blend in with the sky, camouflaging them from enemies below.

The disruptive coloring of some fishes is used to confuse predators. Many fish are known to have the type of protective blotching which makes them resemble some less desirable species. For example, nature has colored one group of nonpoisonous fish with the same stripes and spots as are found on the poisonous fishes.

Also there is the mimic, the fish who is never satisfied to stay one color but must change color every time he changes his habitat. The flounder can even develop spots to match a checker-board background.

There are many causes for the changes in fish coloration. Most are brought about by external factors in the environment such as temperature, light, nourishment, and the combination of all of these.

Trout change color in relation to water and shade. This is due to complicated processes that are triggered when light from the surroundings strikes the fish's eyes. Structural colors, actually in the fish's skin, depend upon reflected light to be seen. Light passes through one layer and is reflected back again to your eye, which interprets the color.

The blacks, reds, silvers, yellows, and red browns are the most common pigments and they are found in the skins of all Utah fishes. Very rarely does one see dissolved blue pigments.

Color is as much a part of the fish's anatomy as a fin. The color cells in the skin are called chromatophores. Each color cell is capable of producing only one color. The melanophore, the cell that is responsible for the black pigment in fish, is the most common. Red is produced by the erythrophores, yellow comes from the xanthrophores. Quicinophores are responsible for silver.

The red cells (erythrophores) are quite predominant in the rainbow and other trout. These change color fastest, the speed depending on temperature and light.

Not all fish are colored. Several species found in underground rivers, lakes, and dark caves have no color pigmentation at all. However, fish with normal pigmentation if placed in total darkness will soon die.

Biologists have a habit of studying all of nature's sides to see how it operates. By injecting chemicals such as acetylcholine in a fish, they are able to expand the pigment cells and cause them and the fish to become darker, while on the other hand, adrenalin will cause the chromatophores to contract, causing the fish to lose color.

One sometimes wonders if all the colors seen on spoons and lures are there to catch fish or fishermen. Can the fish distinguish each color or does he detect only variations in the intensity of color?

Any angler can recall when the fish showed a preference for a particular kind of fly or lure. The fish would hit one particular bait anytime it was placed in their range of vision. It seems certain that in some fishes at least the sense of sight is keen. A trout may refuse a certain fly again and again, but when another of similar size and shape but different color is substituted, it is promptly accepted. This suggests that trout may be sensitive to color, but whether this is the general rule among all fishes is not known. It is not unlikely that the fish really notices movements or changes in outline rather than the actual color of an object.

The study of fish coloration may seem academic at first. But imagine the consequences if a strain of trout developed in one of our hatcheries that could not change color. In a stream they would be easy prey for any predator if they could survive that long. Hatchery production would be curtailed and this in turn would affect fishing all over the state. As the advertising man knows, color is important.

THE END Reprinted from Utah FISH AND GAME

TIMBER For Nebraska

by Jane Sprague First Arbor Day, then Halsey. Now it's Squire Squirrel's turnTHE NAME IS Squire P. Squirrel, a cute, furry little fellow who has done something no other squirrel has been known to do. For Squire P., as he is known to his friends, is giving away his store of walnuts.

Despite the fact his brothers in the squirrel fraternity may think Squire P. has lost his senses, he's a pretty smart creature. He likes nuts, and at the rate walnut and other trees are disappearing from the Nebraska scene, he wants to make sure he knows where his food of the future is coming from.

Squire P. is a dyed-in-the-wool Nebraskan. He realizes that tree planting is a natural here. After all, this is the state where Arbor Day was born, where one of the largest man-made forests, Nebraska National Forest, sprang up in the treeless Sand Hills.

With the rapid rate timber trees are being used all over America, something must be done. According to the U. S. Department of Agriculture, America's timber needs will double in the next 40 years. And America must raise its own timber. This nation can't look to other countries for imports, for every other country will be using all the timber they can raise.

This is one market where there are a lot of buyers in search of sellers. The wood of the walnut tree is a valuable commodity and though it takes at least 80 years before the timber can be harvested, farmers can realize a return from the nuts produced only 10 to 20 years after planting. These are in as much demand as the timber.

Jim Moore, Lincoln landscape designer has always seen the possibility of a timber industry in Nebraska. The one way to develop such an industry is to plant the necessary trees now. To sell his campaign of tree planting, he devised Squire P. Squirrel to serve as a Smokey Bear-type character and show Nebraska the merits of the plan. Governor Frank Morrison, Secretary of State Frank Marsh, the University of Nebraska Extension Service, the United States Forest Service, and the Nebraska Department of Education have all given their support.

The campaign has been launched with the hopes that it will someday assure Nebraska farmers of a$ 1,500,000 return annually from acres now idle. It's a big job to get done, and one that will stretch over many years. But the returns will be great, with many different species of trees covering the Nebraska countryside.

This year, black walnut trees have been distributed and planted. Next year, and in the following years, other valuable seeds will be planted. There will be cottonwoods for the plywood, pulp wood, and crates they can provide; bur oak for its Irish whiskey barrels; Osage orange for fence posts; and pines and firs for safe, fresh Christmas trees.

Nebraska's timber supply has been declining steadily. During two world wars, 75 per cent of Nebraska's walnut trees, one of America's most valuable woods, went to war as airplane propellers and gun stocks. Today its value lies in the timber that can be used for furniture and other wood products, and the kernels that are a valuable food product. Last year, for instance, Kansas and Missouri farmers grossed $500,000 from walnut kernels alone. Besides the timber and food they can provide, the hulls and shells can make good composts for enriching the soil. The shells are used in the packaging of TNT and nitroglycerin. Experiments are currently being conducted on the use of shells in rubber tires, as a prevention against getting stuck in mud. The pulverized

14

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

hulls have also proven a very effective method of cleaning today's jet engines.

hulls have also proven a very effective method of cleaning today's jet engines.

Walnut trees are native to 27 eastern Nebraska counties having the rich, moist soils of river bottom lands and forested hills the trees thrive on. In these 27 counties, there are some 50,000 acres of land lying idle—rough land, areas along streams and gullies, and places unsuitable for farming.

If these unused acres were put to work producing valuable trees, the returns would be enormous. Timber on a one-acre walnut grove will produce on the average of $30 per year. With the 50,000 acres now lying idle, a return of $1,500,000 a year on the average could be brought in to Nebraska farmers. Through this program, 2,500,000 idle acres in Nebraska can be put to work raising valuable trees such as walnut, cedar, pine, fir, bur oak, and cottonwood. The timber industry has a $120,000,000 per year potential in Nebraska.

The planting of walnuts and other trees can put dollars into Nebraska through industry. If the timber and nuts were here, saw mills and nut-cracking plants would spring up, creating jobs and more money. And with the wealth that would be created, the tax burden would be lightened.

Benefits that can't be measured in dollars and cents could be reaped from planting. Wildlife and the land itself would benefit. With the planting of trees and the growth of the interlacing roots, wind and water erosion could be brought under control. Songbirds would find nesting places readily available. Game animals such as squirrels would find food and housing. Burrowing animals could take advantage of the loafing areas the trees would provide and the food that would be available. As the stands of trees grew, ground cover would develop around them, protecting game birds and animals. And the trees would afford winter cover and protection from the snow and cold weather that kills a number of Nebraska's game birds and animals each year.

On March 29, 1961, Squire P. Squirrel got his big tree-planting campaign under way. Sacks of walnut seeds were distributed to 16,817 third graders in 1,054 eastern Nebraska schools in 27 counties. They took the seeds with their planting instructions home, along with a letter to their parents telling them how they could turn their idle land into walnut trees.

Seeds to use in the campaign were collected by farmers whose land already held these valuable trees, Camp Fire Girls and Bluebirds, housewives, and countless other people interested in seeing the dream of a timber industry for Nebraska come true. Federal and state forestry services worked with the program, germinating the walnut seeds to be ready for the children to plant. It was a big job, but with lots of help, the campaign got an ample start toward reaching its goal.

The children received their walnut seeds, enthusiastically planted them, and waited for the first sprout from the deeply planted seeds. The governor planted a seed on the lawn of the Capitol Building. Today, that seed is starting to show signs of growth, as are many of the children's plantings. Definite results are not yet known, but the picture looks good.

Distributing the seeds and educating the school children and their parents on the merits of the plan are only two phases of the work that have been cut out for the Squire P. Squirrel campaign. The program encompasses a good many other things.

Ways must be devised to help the farmers wisely market their timber by developing an effective and orderly marketing system. A method is needed to ensure collecting seeds only from the best trees and exploring all the possibilities of certification and hybridization of tree seed. Nebraska could profit through the testing of "new" trees on test plots in Nebraska's five planting zones. Effective methods of pest and disease control are needed, as well as methods of educating the farmer in the detection of these pests and diseases. The individual farmer should be given every possible assistance in the management of his wood lot or timber area.

This is a program for people who are far-sighted, who aren't looking for rewards that will be immediately available. They are looking ahead to the future when their children will be reaping the gifts the trees have to offer.

THE END OCTOBER, 1961 15

DEAD TIMBER

by Wayne Tiller Here at Elkhorn retreat are river, bluffs to climb, and fish to catchONCE PAST THE rustic entrance pillars, the carload of picnickers is greeted by a refreshingly scented breeze blowing through the pines and cedars that rise above the rolling farm land. Birds dash from tree to tree and squirrels stop their noisy chattering to watch the car pass below. As the signs announced on U. S. Highway 275, this is Dead Timber Recreation Area, 25 miles north of Fremont. The area is one mile east and a half mile south of the highway.

Ash, oak, and maple trees come into view as the car follows the park road down the hill, over a rustic bridge, and into the picnic and camping area. Here's the oasis the family has been looking for, a 200-acre play land of bluffs and trees where the kids can let off steam; where Mom and Dad can relax and enjoy the sparkling beauty of fall.

Originally a curve of the Elkhorn River, Dead Timber Lake is now an isolated oxbow completely separated from the stream. The Game Commission

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

has managed the popular play area since it was acquired in 1938.

has managed the popular play area since it was acquired in 1938.

The clean, well-managed picnic and camping area features tables, fireplaces with wood, approved drinking water, and sanitary facilities. Playground equipment including swings, a merry-go-round, and seesaws are nearby. A log pavilion complete with fireplace and made to order for wiener-marshmallow outings round out facilities. All are geared to make your stay enjoyable.

A special area in the southeastern corner of Dead Timber is reserved for trailer travelers. There is no charge and a camper may stay as long as 14 days if he occupies the trailer daily.

Primarily noted for squirrel hunting, the area offers some waterfowling and rabbit shooting. A host of raccoons call Dead Timber home. Other animals common to the area are deer, moles, shrews, fox, muskrats, skunks, mink, weasels, ground squirrels, the usual variety of small rodents, and an occasional opossum.

Visitors are almost invariably tempted to try their luck in the placid waters of the meandering lake. Lucky fishermen creel an occasional bass, and bluegills, perch, and bullheads provide sport for young and old alike.

Motorboats are not permitted due to the narrowness of the lake. This guarantees that the peaceful tranquility will not be disturbed.

A foot bridge spans one neck of the lake. A favorite of many younger visitors, the bridge leads from the level camping grounds to the high bluffs that shelter the area from the cold winds of winter. Here children move into the world of make-believe, the steep bluffs becoming forts, castles, or frontier outposts. They'll never forget hiking and exploring in this unique area.

The heavily timbered bluffs provide a compact woodland community that attracts numerous animals from the nearby river. Woodpeckers, kingbirds, owls, and numerous kinds of songbirds can be studied. The area is also used by mourning doves.

The unique beauty of outdoor Nebraska stands ready for the exploring eye and listening ear of the naturalist at Dead Timber. Fish are in the lake for the angler's hook. And shady campgrounds with picnic tables lure the tired traveler. Visit this oasis on the Elkhorn soon.

THE END

October's BIG FOUR

by J. Greg Smith Action aplenty awaits goose, grouse, deer, and duck huntersNEBRASKALAND HUNTING rolls into high gear this month, with plenty of new targets ready for state hunters. Both mule and white-tailed deer, prairie chickens and sharp-tailed grouse, and a variety of ducks and geese are primed for plenty of action. Of all the October targets, only ducks mar the otherwise rosy hunting picture.

Deer will be gunned on a state-wide basis for the first time in modern hunting history, beginning October 28. All 93 counties will be open. Some 14,000 rifle permits for antlered deer have been authorized in the 17 management units, with a bonus of either-sex gunning on the last day of the five-day season in five of the units. Archers have been hunting statewide since September 16. The either-sex hunt continues until the opening of the firearm season. Once it is over, the archers may again take to the field through December 31.

The grouse population is up, thanks to good reproduction this summer. Uplanders may hunt these wily birds for 23 days. The season opens October 7 and continues through the 29th, with a bag and possession limit of two and four.

Goose hunting should be as good as last year. The 60-day season is designed to catch both early flights in the east and late migrants in the west.

Nebraska's duck season has been geared to provide the maximum amount of recreation within the limitation of the population. Drought was the real culprit behind this year's flyway duck decline. In Nebraska, the picture is different. Local production was above the average of the last six years with only the rain-water basin showing a decline in nesters. These locals along with the big flights moving through the state, should provide plenty of sport during the 40-day season.

That's the hunting picture. Get your gear ready. You'll be in for plenty of action. To help you enjoy your hunt, OUTDOOR NEBRASKA is featuring detailed where-to, how-to, and when-to information on the next four pages. It should prove helpful in making this year's seasons the best ever.

When, Where, How-to

When, Where, How-to

LOOK FOR MULE deer in the western part of Nebraska, whitetails in the east, with both species overlapping the middle of the state. In 1960, hunting success was generally higher in the central and western management units. Most of the trophies, however, came from the more timbered eastern region which was recently opened.

The Pine Ridge, Platte, Keya Paha, and Missouri units and part of the Sand Hills Unit will offer either-sex hunting on November 1. All other areas are limited to bucks only throughout the season. Shooting hours are one-half hour before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset.

Nebraska's two deer species are as different as night and day, and you'll have to gear your hunting style accordingly if you expect to bring home game. The whitetail is crafty and sticks to brushy cover. The mule deer, on the other hand, is curious and inhabits more open country.

Deer are more active in the early-morning and evening hours. They rest during midday, selecting areas where they can spot intruders. Their senses are acute. Eyes, ears, and nose are all tuned in on anyone or anything that spells trouble. Stalking either species in brushy cover is almost impossible. The deer, warned by the rattle of the brush, will be long gone before you get within range.

The smart whitetail hunter will select a stand and wait for the game to come to him. He must be prepared to shift with changing wind patterns and make sure he's well hidden. And even with all of this preparation, the hunter may go home blanked because his target took another trail.

Whitetail in an open field can be stalked. The trick here is to move up quietly while the deer is feeding. When he looks up, don't move a muscle. More often than not, you'll be just another tree and can get close enough for a shot.

The mule deer, being curious, can be tricked into posing for shots. A yell or whistle will often stop him in his tracks. There's another way to take advantage of this weakness. Have your hunting partner hold the deer's attention while you move in behind.

A variety of guns may be used on deer. State law requires that a gun must deliver 900-foot pounds of energy at 100 yards.

GROUSEPRAIRIE CHICKENS and sharptails appear unpredictable to the novice hunter. But to the seasoned shooter, on to their tricks, they prove challenging targets but can be readily bagged. The successful hunters know the birds, and get out and work for them.

The Sand Hills has historically been the stomping grounds of both the prairie grouse. Prairie chickens, or pennated grouse, are concentrated around the border while sharptails are found throughout the vast area.

The area open to hunting is bordered on the west and north by the Wyoming and South Dakota state lines, on the east by U.S. Highway 81, and on the south by the Platte and North Platte rivers. Shooting hours are from sunrise to sunset.

Hunt the cornfields, stubble-field edges, and meadows in the early morning hours. As the day becomes warmer, try clumps of brush or shelter belts where the birds will be loafing. Sharptails generally take to the tops of the choppy Sand Hills during midday where they can take advantage of the cooling breeze.

Prairie chickens follow much the same pattern. Both species will migrate back to the valleys by 4 or 5 o'clock in the afternoon. Then red clover, stubble, and alfalfa fields prove productive.

If none of these areas pay off and you have lots of energy, take to the hills. Here's where a good pointer or setter will come in handy. They'll not only spot the birds but retrieve them once they're downed.

Grouse often tend to flush wild and it may be difficult to get in range, especially on windy days when they are scattered through the grasslands. The birds band together with the approach of cold weather. When flushed, they may fly one-half to two or three miles before alighting. When they hit the ground they stick to it.

Only shotguns may be used in taking prairie grouse. Shot size ranges from Nos. 6 to 7% with some hunters going into Magnum loads later in the season when the grouse flush at more distant ranges.

OCTOBER, 1961 19

NEBRASKA'S 2,000 Sand Hills lakes, the rain-water basin area in the south-central part of the state, and major river systems will soon feel the brunt of migrating waterfowl swooping down from the north. These sites promise good action within the limited duck season. All are considered prime hunting spots.

Lakes in the Sand Hills should provide some good early shooting. This area produced a fine crop of birds this year and many of the locals should be around during the first week of the season. Blue-winged teal will probably be gone by that time, as well as some pintails. Baldpate and gadwalls will be departing between mid and late October. Other ducks will move in, with the big flights of mallards pulling in at about the time Nebraska birds fly south.

Jump shooting pays big dividends on these small lakes and marshes. No decoys are needed here, just a good pair of waders and a strong constitution. The trick is to stay low and keep some cover between you and the birds resting on the water.

Hunting will move to the rivers with the advent of cold weather. Waters like the Platte and Missouri have long been leased up tight. The neophyte will find it difficult to get on them without making local contacts before the season opens. All hunters, of course, need the landowners' permission.

Decoy hunting is the most popular and effective method of hunting on the big rivers. Ducks and geese trade between river and grain field in early morning and late afternoon. They are more easily decoyed during the middle of the morning when they return from the fields with their crops full of grain. Hungry ducks, on the other hand, usually make a beeline for the fields, paying little attention to even the most attractive spread.

Those not fortunate enough to get on the rivers should take a crack at pass shooting. This requires a good knowledge of bird movements. Pick a spot that offers good natural cover and wait for the ducks to fly within range. But be sure and wear plenty of warm duds to fend off the cold during the long wait.

Geese are as unpredictable as they come. They'll sometimes spot even the best setup and the next time fly in with the hunter in full view. Sneak shooting is especially difficult since the big honkers always have a couple of birds on the lookout for intruders. Blind or pit shooting is the most effective way of getting ganders.

Though many of the prime water areas are sewed up tight, the waterfowler can still get plenty of action on the big reservoirs as well as state recreation and special-use areas. McConaughy, Maloney, and Johnson lakes are top waterfowl spots among reservoirs on the Platte. So are Enders, Swanson, Medicine Creek, and Harlan reservoirs on the Republican. Lewis and Clark on the Missouri is prime. Smith Lake, Ballards Marsh, Rat and Beaver Lakes, Long Lake, Sacramento, and Two Rivers head the list of other state areas offering top hunting.

The duck season opens at noon, October 28, and continues through December 6. The 60-day goose season opens October 1. The two-and-four bag and possession limit for ducks may not include more than one wood duck and one hooded merganser. Both the canvasback and redhead are again protected.

The five-and-five goose limit may not include more than one white-fronted goose, or two Canada geese or its subspecies, or one Canada goose and one white-fronted goose. Shooting hours are from sunrise to sunset.

Only shotguns may be used in waterfowl hunting.

Game Care

THE SMART HUNTER knows that the hunt doesn't end with the bagging of game. Only proper field care will make his outing a real success.

Dressing ducks and geese in the field is literally a matter of taste. Most hunters prefer to let the carcass cool before drawing the birds. A few even go so far as to leaving the birds intact two or three days, contending that it adds to the taste.

When it comes to deer immediate field care is all-important, for you are gambling many pounds of venison. The first step after tagging your animal is to sever the arteries and veins around the breastbone, and bleed the animal. Next, cut out the musk glands inside the hocks. These may cause tainting of the meat if left intact.

Now make a small incision in the midline of the stomach just to the rear of the breastbone, and begin cutting to the rear, using your fingers to lift the skin. Be careful not to puncture any part of the digestive tract. Cut to the crotch and completely around the anus. Then cut deeply to the bone and split the center pelvic arch. Tie off the anal tube and pull the rectal area into the body cavity. Working forward, cut the diaphragm close to the chest wall and pull the heart and lungs into the cavity. Reach as far up the neck as possible and pull out the windpipe. This done, turn the carcass on its side and dump the entrails and lungs. Put the liver and heart in a cloth bag to keep them clean and cool. Once the breastbone is split, the deer is hog-dressed.

Let the carcass cool before transporting it home. Be sure that the deer is placed in an area where it can cool properly during the trip. A car-top carrier is ideal. Never drape the carcass over the car's hood or fender where it receives engine heat.

Remember to have the deer checked and sealed, and that waterfowl must have head and feet attached at all times.

DUCK CARE

Game Recipes

OCTOBER'S BIG FOUR continuedThere are a number of ways to prepare waterfowl. Knowing the age of the bird is all important. Older birds must be cooked longer and should never be served rare or medium. Ducks should be placed in salt-water brine (about 2 tablespoons salt per quart of water) and left in a cold place overnight. This removes strong flavors and blood clots.

Roast DuckWash bird thoroughly and dry carefully. After drying, stuff with dried bread or fruit. Fold wings back and brush with melted fat. Roast in moderate oven, 20 minutes per pound. During the last half hour of roasting, baste the ducks with wine sauce.

Broiled DuckSoak birds in cold-water brine overnight. Remove and dry. Cut back and neck and truss legs and wings together. Salt and pepper and cover the breast with strips of salt pork. Broil from 18 to 20 minutes. Remove from broiler and take off salt pork. Place in skillet containing the following sauce: 4 to 6 tablespoons drippings, 2 tablespoons currant jelly, 1 cup sherry wine, 1 teaspoon celery salt. Stir until jelly is dissolved. Thicken with flour and water mixture. Bring to boiling point and place broiled duck in sauce. Cook until done. The duck may be served off the grill with the sauce served on the side.

Roast GooseSoak overnight in cold-water brine. Remove and dry thoroughly. Salt and pepper the cavity. Place quartered chunks of apples, onions, and celery in the cavity. Sew up tight. Tie thin strips of salted pork over the breast. Cook breast-side down in a closed roaster with enough water to assure that the breast of the bird will be covered. Cook at 350 °F. until tender. Remove half the liquid, turn goose breast-side up and brown. Baste occasionally and keep salt pork on the breast. Remember, older birds require longer cooking.

Deer MarinadeMince Vz pound carrots, Vz pound onions, Vz pound celery. Fry in lard or oil. Add 1 quart water, 1 quart vinegar, % cup sugar, 1 bunch chopped parsley, 3 bay leaves, 1 bunch thyme, Vz teaspoon basil, V2 teaspoon cloves, 1 teaspoon crushed whole pepper, a dash of mace, 1 teaspoon allspice, and 2 tablespoons salt. Simmer for Wz hours and chill.

Deer SteaksCut Vz inch steaks from the loin. Remove all fat and fiber. Marinate. Season to taste and fry in butter. Serve immediately on warm plates.

DeerburgerRemove the fat from the meat to be ground. Blend 4 parts deer meat with 1 part beef leaf fat. Grind, freeze, and use as you would ground beef.

Roast VenisonUse either rump, round, or standing-rib roast. Trim off all fat. Marinate, inserting a sharp knife into each square inch of the surface to allow liquid to penetrate. Let it stand for 24 hours. Remove, drain, and refrigerate till meat becomes firm.

Cover roast with beef suet and bacon and cook uncovered in 325 °F oven. Allow 25 minutes per pound. Baste with juices.

Deer LiverWash the liver carefully and soak in salted water. Cut in thin slices. Season with salt and pepper and dust with flour. Cook in bacon fat till done. For variation, brown onion in butter and place the fried onions on the liver when served.

Roast GrouseSoak in brine. Clean and dry thoroughly. Stuff with favorite dressing. Cover with strips of bacon and roast until tender in moderate oven.

Gourmet's GrouseSoak in brine. Remove and dry thoroughly. Cut in sections, season, flour, and brown in y4 pound butter. Add 1 cup soup stock, lemon juice, 1 finely diced onion, 4 finely diced carrots, parsley, 2 cloves, 3 bay leaves, and 4 peppercorns slightly crushed. Cover and cook until tender. Add Vz cup Burgundy wine 30 minutes before done. Do not smother bird with liquid.

Fried GrouseSoak in salt-water brine. Remove and dry thoroughly. Cut into frying-sized pieces. Salt and pepper and fry in 4 tablespoons fat. Cook until thoroughly browned. Once browned, turn the heat low, cover, and cook until tender. Turn several times.

22 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

PENNSYLVANIA . . . Two men claimed a 200-pound bear killed on the last day of Pennsylvania's 1960 bear season. This wasn't (t^f r^3 surprising, considering the circumstances. Each hunter was using a 30-30. Both fired the same kind of cartridge, and the two rifles boomed simultaneously. To make the coinciddence complete, one man shot the bear back of the shoulder; (you guessed it) the other shot the animal in the same spot on the opposite side.

After piecing together what must have occurred in the one-in-a-million incident, the hunters agreed to a friendly division. One man attached his kill tag and agreed to accept the head as his evidence of success. The other hunter properly tagged and took the hide and carcass.

Flowering UnappreciatedMINNESOTA . . . The state "litter-bug" is far from an extinct species. State taxpayers last year put out over $215,000 to remove litter from some 11,000 miles of highways. Over 8,000 truckloads of trash were picked up. On lesser traveled roads, litterbugs have deposited trunk loads of garbage on road shoulders. Other bugs dump refuge down embankments, sowing a lovely summer bloom of beer cans, bottles, papers, and other assorted junk. This flowering of litter is there to be appreciated by sportsmen, boaters, and the young folks—many of whom are not full-feathered bugs yet but must be trained, through adult example.

NEW YORK . . . Acousticon International has noted a growing market for its hearing aids among hunters who use the amplifying instruments in stalking game. Now it reports a new off-season market. Game wardens are buying hearing aids as an assist in tracking down poachers.

Cock of the RockPENNSYLVANIA ... A young deer about to cross the highway caught the eye of a Game Commission land manager who had a ringside seat at the battle which later developed. As the car-wary deer ran back into the field a ringneck pheasant came out of the cover and challenged the buck. The deer, apparently in a playful mood, made several passes toward the pheasant as if to trample it. The old cock not only stood his ground, but charged, jumping at the deer's face and striking out with his spurs. The deer took off for heavy cover and the pheasant had the battle-ground to himself.

Exotic ProblemAFRICA ... A missionary's wife may have been the unsuspecting culprit in causing Kariba, one of the world's largest man-made lakes to be blanketed with a fern native to South and Central America. The first signs of the plant were a few floating fronds on the lake in March 1959. In a little over a year it spread to cover 200 square miles and today is growing faster than ever. The present area of the lake is 1,000 square miles.

Sure SuicidePENNSYLVANIA . . . Seeing a woman aiming a .22 rifle at a rock pile in Bedford County one day early this summer, a game protector assumed she was trying to kill a snake. The appalled man watched as she fired into the stones, then explored them by probing with the business end of the barrel. Finally she turned the rifle end for end, held it by the barrel, and used it like a wrecking bar to pry the larger stones apart.

Mused the officer, 'It's almost certain that if she continues this I'll meet her relatives while investigating her hunting accident."

Bathtub DeerCALIFORNIA . . . One of two local men was turned over to wardens recently after an Oakland Police officer stopped him for a traffic violation and found a deer carcass in the trunk of his car, together with a rifle and spotlight. Further investigation led to the other man's apartment. There three deer carcasses were found in the bathtub. One suspect, identified in court by the other as the man who shot the deer, was sentenced to six months in jail; the other drew a three-month sentence.

NEW ZEALAND ... If you don't mind travelling a few extra miles for your game, you'll be in on a deer hunter's paradise in New Zealand. Plagued by a glut of deer, authorities are permitting hunters to take all they want, anytime during the^ year without a permit, and they even furnish the shells. They've even gone to the extent of hiring professional huntters, but the deer are still gaining, causing serious erosion problems.

Man With PullOKLAHOMA . . . Anglers, always interested in new gimmicks to add to their sport, will really take to the idea of an Oklahoma City man. He keeps a powerful alloy magnet in his tackle box. Its purpose—to retrieve hooks and other metal gear that goes astray. Recently his investment paid off when he recovered $30 worth of fishing tackle from a lake.

OCTOBER, 1961 23

COWBOY'S DOG

(continued from page 9)an extra cowhand. She had a quick way of sensing which critter needed special attention. The dog would alter the stubborn animal by giving a neat nip at the rear hock and get it going in the right direction.

Only once did I regret not having Fanny along to help in a critical situation. Three of us were sent to move about 1,000 Texas longhorns from Cottonwood Creek to a feeding ranch on Plum Creek. Just after the outfit left the pasture a tumbleweed blew in front of the herd and started a stampede. The longhorns ran for nine miles, leveling fences and sheds like a tornado. They finally stopped, completely exhausted. The thrill, excitement, and terror of the stampede is a story in itself, but I'm sure Fanny could have helped in the situation. But she would have a turn at the critters soon enough.

Part of the profit in ranching in those days was to keep hogs with the fattening cattle. They picked up the wasted feed. The longhorns we drove in weren't used to having hogs underfoot. We hadn't been able to dehorn and that only added to the problem.

The longhorns seemed to have a defense that they introduced into the feedlot. On the prairie, I was told, coyotes, wolves, and other predators would be rounded up inside a circle by the longhorns. Then they would move in closer with their horns down. The meat eaters couldn't escape between the forest of legs and would be speared by sharp horns. The beeves were all for trying their trick on the hogs. Several times each day we heard piteous squeals.

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS 10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 CUSTOM GUN-STOCK WORK. Rifle, shotgun, and pistol grips. Bill Edward, 2333 So. 61st, Lincoln. Ph. IV 9-3425. MOUNTING DEER or antelope head, $25. Mounting average size black bear rug, $40. Mounting coyote or bobcat rug, $15-$18. W. H. Strange, Nebraska City, Nebraska. VIZSLA pointer-retriever puppies and started dogs by field-trial winners. AKC, FDSB. Graff's Weedy Creek Kennels, Route No. 3, Highway 15, Seward, Nebraska. Phone 8647. AKC REGISTERED BRITTANY SPANIELS for sale. From popular blood lines. Natural hunters, loyal pets, reasonably priced. Some old enough to start training. C. F. Small, Atkinson, Nebraska. AKC BLACK LABRADORS: Two litters sired by triple Champion, Boley's Tar Baby. Dams by National Champion Yankee Clipper and his brother. Few started Labradors and young Brittanys. Kewanee Retrievers, Valentine, Nebraska. Phone 26W3. FOR SALE: Golden Retrievers. Puppies, AKC, sired by CH.J's Golden Gunner C. D. Combination of field and bench show blood lines. Pedigree available. Alvin Syring, Box 705, Hastings, Nebraska. MODERN TAXIDERMY: Game heads, animals, birds, fish, rugs, novelties, and deerfoot lamps. Otto Borcherdt, Taxidermist, 2155 South 9th Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. Phone 477-5003.One afternoon Gus and I were unloading hay when we heard the loud squeals of a wounded hog from a nearby pen. Gus whipped up the horses and I ran and opened the gate of the lot where nearly 100 longhorns were surrounding a bleeding porker. Gus again whipped up the horses, hoping to rush the steers now bellowing after smelling the blood. He wanted to break up the cattle and get the wagon over the hog. He succeeded in getting into the circle all right, but the steers decided to take on the wagon.

We had to do something quick. The horses reared on their haunches as the longhorns moved in.

"Grab a fork," Gus yelled. "If they start tipping the hayrack, spear them as fast as they come."

But I knew that more blood would only mean more trouble. Then I thought of Fanny. Gus whistled and she came on the run. In less than a minute she was over the gate, under the legs of the crazed beasts, and into the center of the arena.

"Sick them," Gus yelled.

Immediately she darted through to the rear of the nearest longhorn and gave that sharp neat nip which caused the animal to turn and start running. This was repeated on about a half dozen of the other leading steers. In less time than it takes to tell it, she had the whole herd rushing to the rear of the lot. Again Fanny had saved the day.

Fanny played the heroine on still another occasion. The company had built a new barn with a very large hayloft. It had been filled with loose new-mown hay. One day Vernie and his little sister, Myrtle, decided to play in the hayloft. Fanny, as usual, went along as their faithful companion.

The children had a place to the rear of the loft and quite a distance from the stairway. They were playing house, which included starting a little fire. Neither realized that the loose hay was as good as tinder. As expected, the worst happened, and the

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

loft was quickly filled with smoke and fire. The children were dazed and afraid, not knowing which way to go. Fanny quickly sensed the danger and led little Vernie and Myrtle to the stairway and out of the barn, then barked the alarm.

loft was quickly filled with smoke and fire. The children were dazed and afraid, not knowing which way to go. Fanny quickly sensed the danger and led little Vernie and Myrtle to the stairway and out of the barn, then barked the alarm.

These are just a few of the extraordinary events in Fanny's life. But she lived a life of silent companionship and service. One amusing incident illustrates this.

One day when Vernie and his Dad were down near the clear pool in Plum Creek, the lad boasted that he could swim. He was only 7. Gus was astonished. As far as he knew, no one had taught the boy to swim.

"All right," Gus said, still unbelieving and ready to jump in if anything happened, "take off your pants and let me see you do it."

To his amazement, Vernie plunged in and dog-paddled across to the other side. When Gus asked who taught him how to swim, the boy said he watched Fanny.

Humans have memorials in bronze and stone as well as biog raphies telling of their lives of service and self-sacrifice. Fanny needs none of this. Her faithfulness will never be forgotten. Not by me. Not by any who knew and loved, her.

THE ENDSPEAK UP

Send your questions lo "Speak Up", OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, State Capitol, Lincoln 9, Nebr. State s Paul Bunyon"Do you know of any written material about Nebraska's strong man, Antwine Barada? I know he was a fur trader and was buried in the town of Barada, Nebraska. He was my great grandfather and I would like to know more about him."—Nora Barada Murphy, While Cloud, Kansas.

Antwine Barada in legend was Nebraska's answer to Paul Bunyon. In actuality, he was a part-Indian, part-French fur trader born close to Fort Calhoun north of Omaha in the early 1800's. His colorful and exciting life is portrayed in an article entitled "Nebraska's Antwine Barada" that appeared in the Nebraska History magazine, Vol. 30, September 1949. Additional information may be obtained from the Nebraska Historical Society, publisher of the magazine.—Editor.

Good Suggestion"I want to commend you on the fine work you are doing in your magazine OUTDOOR NEBRASKA. Formerly from Hastings, I am presently stationed at Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. It's really nice to know what is being done in the home state toward improving outdoor recreation prospects. For families with men in the service that are interested in the outdoors, I strongly recommend a subscription to OUTDOOR NEBRASKA to keep them posted on things back home."—Gary L. Reed, U.S.M.C, Hawaii.

Posted to Whom?"Would you please settle an argument "or us? If a landowner posts his land with 'No Hunting' signs, can he still hunt on it himself? Can he give permission to his friends to hunt on this land, providing that all parties concerned have the licenses and stamps required?"—L. L. Juergens, Superior.

A landowner may post his property with signs while hunting on the land himself and inciting friends to hunt with him. At the same time, he can charge any other person on the land with trespassing. Permission is required to hunt on any privately-owned lands whether it be posted or not, and anyone without that permission is trespassing.— Editor.

Plans for Turtles"Your article 'Truckful of Turtles' in the August issue interested me greatly since I live in Cedar Rapids, not more than a block from the Cedar River. About every other nieht I set lines for catfish in the river but catch few due to the turtles. Can you tell me where I can get plans for making a turtle trap? We eat the turtles I now catch occasionally on a hook and any I would catch in a trap would not be wasted."—John Rupprecht, Cedar Rapids.

The traps are made of three to four-inch mesh wire with a long funnel throat in one end. As the turtle follows his nose to the bait and crawls ur> on the throat, his weight opens the funnel wide enough for him to crawl through. We do not have any plans but can furnish you with a sketch.— Editor.

Otters Helped"The letter to 'Speak Up' in July about otters caught my eye. (The letter writer, A. F. Magdanz, Pierce, said he had taken otter, now extinct, on the North Fork of the Elkhorn in the 1890's.) I have done a lot of digging into the history of Nebraska wildlife, and to my knowledge, this is the latest date on record for this species.

"Looking at the 1890's, I think we can find the reason for the disappearance of the otter about this time. Nebraska going into this decade probably had more people living in rural areas and small towns than at any other time. Then the dry years came and just about everybody that was able, had some place to go, and means to go, left the state. Those that stayed had a hard time without crops, and turned to trapping to make some money. Many species of wildlife went to help make a living for those that stayed.

"I would like to know if anybody has any later dates for otters in Nebraska."—John Beck, Grand Island.

Nebraska Salmon"Can you give me a recipe or information about how to make 'salmon' from the fish we catch in Nebraska? I feel that if we had a way similar to that used to soften the bones of salmon we buy in cans, we could have meat just as good from Nebraska fish." —I. G. Souba, Columbus.

The process of canning salmon includes a period of pressure cooking that softens the bones and somewhat changes the taste of the meat. The following recipe will render carp almost as tasty and will soften the numerous bones.

1. Skin the fish and remove the dark meat line along both sides and the feather-like bones just behind the head. 2. Fillet the meat into 3-inch-square chunks about iy2-incfies thick. 3. Pack firmly in a pint cooking jar, add 1 teaspoon salt to season, and a small amount of water to keep the meat moist. 4. Cook under 10 pounds pressure for 2 hours.Perhaps some of our readers will submit other recipes for cooking rough or bony fish.—Editor.

GAME BIRD BREEDERS, PHEASANT FANCIERS AND AVICULTURISTS' GAZETTE A generously illustrated pictorial monthly carrying pertinent bird news from around the world. Explains breeding, hatching, rearing, and selling game birds, ornamental fowl, and waterfowl. Practical, instructive, educational, and entertaining. Advocates the protection and conservation of disappearing species of wild bird life. The "supermarket" of advertising for the field. Official publication of AMERICAN GAME BIRD BREEDERS COOPERATIVE ASSOCIATION. THE INTERNATIONAL WILD WATERFOWL ASSOCIATION, AMERICAN PHEASANT SOCIETY, and many other game-bird societies. This periodical is subscribed to by bird breeders, shooting preserve operators, game keepers and curators, hobbyists and aviculturists, owners of estates, zoos, educational institutions, libraries, aviaries, government qgencies, conservationists, etc. One year (12 issues) $3.50 Samples 50c Send subscription to THE GAME BREEDERS GAZETTE O.N., ALLEN PARK DRIVE, Salt Lake City 5, Utah OCTOBER, 1961 25

notes on Nebraska fauna...

COOT

HERBERT K. JOB wrote of the American coot, "If there is a more amusing bird anywhere, I should like to see it . . . their odd ways make one laugh, and I recommend the funny coot as an antidote for the 'blues'." Fulcia americana americana is a common summer resident in Nebraska. Many are found here, particularly in the Sand Hills and rainwater basin.

Although somewhat duck-like in appearance and behavior, the coot is not a duck. He belongs to the family Rallidae which also includes the rails and gallinules.

The coot is a blackish or slate-colored bird with a white chicken-like bill and a white frontal plate. The under tail coverts are white and the legs are greenish. The sexes are similar, but the juveniles are duller colored than adults, show some white below, and do not have a fully-developed frontal plate until late summer of the second year.

A coot's foot is curiously formed. It is not webbed like the ducks. The foot has been described by some naturalists as appearing half-webbed, with deep-cut membranous scallops occurring along the sides of each toe. This arrangement allows the coot to run across the water with the assistance of his wings.

This bird is frequently seen swimming on open water of marshes and sloughs or walking about on land, occasionally far from shore in search of food. The head has a constant pumping motion when swimming or walking, bobbing in time with the foot movements while on land.

On water he floats high with the back level. When rising from the water, he reminds one of an overloaded aircraft which has difficulty becoming

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

airborne. This clown of the waterfowl world never rises off the water without running rapidly across the surface. These runs usually extend at least 50 feet before the bird becomes airborne. In flight some white may show on the trailing edge of the wing, the neck and legs are extended, and the feet protrude behind the tail. Unless hunted heavily, the coot is unwary, preferring to run across the water with flapping wings to the safety of open expanses of water rather than to fly.

airborne. This clown of the waterfowl world never rises off the water without running rapidly across the surface. These runs usually extend at least 50 feet before the bird becomes airborne. In flight some white may show on the trailing edge of the wing, the neck and legs are extended, and the feet protrude behind the tail. Unless hunted heavily, the coot is unwary, preferring to run across the water with flapping wings to the safety of open expanses of water rather than to fly.

By no means a songster, the voice has been compared to "coughing sounds, frog-like plunks, and a rough sawing or filing kuk-kawk-kuk, kuk-kawk-kuk, as if the saw were dull and stuck."

The American coot is widely distributed over a large part of North and Central America and extends into the West Indies, at least into the northern part of the region. The general wintering range is the southern United States, coastal areas, and Central America.

One of the early migrants north, the coot sometimes appears on the breeding grounds in early spring before the ice has completely melted from the lakes and marshes. Upon arrival the birds disperse to the marshes and sloughs where they build their nests, usually of rushes, reeds, and grass stems. Coots are gregarious in nesting but are extremely pugnacious in defense of their nesting territory. Their aggressiveness is not limited to other coots but may also be directed toward other waterfowl who encroach upon their territory.

The nest is usually constructed upon a platform of marshy growth of the previous year. It may be a floating structure but does not move about since it is attached to reeds. The smoothly-lined nest may be partially or well-concealed with the inner cavity hollowed only enough to hold the eggs.

The 8 to 12 buff-colored eggs bear many small specks of black. Incubation lasts 21 or 22 days but begins with the laying of the first eggs, resulting in an irregular hatch. Both male and female share incubating and rearing duties. When hatching begins, the male leads the newly-hatched young off to feed while the female continues to incubate the remaining eggs.

The young coots are highly active soon after hatching. They leave the nest almost immediately and can swim and dive as well as adults. The adult coots may use crude "brood" nests after the eggs hatch.

A wide variety of both plant and animal matter is included in the coot's diet, but nearly 90 per cent of the year-round food is composed of plant-food items. Principal plants include pond weeds, sedges, algae, and grasses. Animal food items are generally insects and mollusks. These are taken most frequently in the summer when large numbers become available.

The coot is an excellent diver and can go down as far as 25 feet for food. When diving, he propels himself by feet alone, in most instances keeping his wings pressed close to the body. Though the coot is a fine diver, he is primarily a dabbler and grazer when feeding. The bird gets his food from or near the surface of the water and often from along the shore. He may also venture some distance inland in search of food.

In highly local areas a large concentration may cause damage to rice fields, particularly in some areas of California. In these sites, special seasons have been held to control their numbers. Generally though, the food habits are inoffensive and create few economic problems, although large concentrations may deplete the food supply of a lake for other waterfowl.

Presently, the coot does not enjoy much stature as a game bird. But one has only to examine the history of waterfowl hunting in the United States to realize that this species will be far more important in the future. Even today the bird is more sought after in areas of high hunting pressure than it is in Nebraska. Many hunters claim that the coot does not have desirable table qualities, but an imaginative wife with patience may transform the bird into a table treat.

As they braved the cold of early spring on the northward migration, coots usually defer southward movement until the last possible moment, often until ice forms on the lakes. Then the birds return south to winter on lakes and brackish sounds, lagoons, and estuaries. But, with the ceaseless cycle of migratory waterfowl, the coots will again become a part of the life of Nebraska marshes and ponds next spring, providing an antidote for the "blues" with their curious appearance and amusing behavior.

THE END OCTOBER, 1961 27