OUTDOOR Nebraska

SEPTEMBER 1961 25 cents HUNTING KICKOFF page 3 BLACK CHAMPION page 10

OUTDOOR Nebraska

September 1961 Vol. 39, No. 9 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION, AND PARKS COMMISSION Dick H. Schaffer, Editor STAFF: J. Greg Smith, managing editor; Mary Brashier, C G. "Bud" Pritchard, Wayne Tiller, Bob Waldrop

HUNTING KICKOFF

• squirrel • cottontail • antelope Low-down on trio of targets is primer for top fall gunningRABBITS HAVE MADE a dramatic comeback, squirrels are as abundant as ever, and the pronghorn population is up; that's the word from Game Commission technicians on the eve of the fall hunting season. This encouraging report is the kickoff to what promises to be a good year afield.

The cottontails, long known for their reproductive abilities, have taken a big step toward recovery from the population decline caused by the hard winter of 1959-60. Prospects for fall and winter cottontailing are good. The year-long season and liberal bag and possession limits of 10 and 30 promise plenty of recreation. Actually, the cottontail could take a lot more pressure.

Nor are squirrels being utilized. The bushytails thrive in eastern Nebraska and are found along stream courses throughout the state. The comparatively few sportsmen out last year enjoyed top hunting. This year should be no different. The season opens September 1 and continues through January 15. Bag and possession limits are 5 and 15.

More hunters will be hunting more antelope this year. Pronghorns have increased in all management units but the North Sioux area. And though this unit dropped because of hunter harvest and trapping and transplanting operations, it continues to support the largest density of antelope. Come September 16, 800 permit holders will take to the panhandle in an either-sex hunt. The season continues through September 18 with a limit of one pronghorn per hunter.

That's the status of the three species. On the next four pages, you'll find the answers to how, where, and when to hunt, recommended field-care procedures, and choice game recipes. Good hunting.

WHERE. WHEN-TO

COTTONTAILSOUTHEASTERN AND PARTS of central Nebraska would be considered prime, the eastern third of the state, excellent, and all water courses good for cottontailing this year. All have ideal habitat for the rabbit.

The cottontail made a real comeback following a decline after the long snow in 1959-60. He, along with the bobwhite, felt the full brunt of the storm, especially in southeastern Nebraska. Counts of cottontails during bobwhite whistle surveys revealed a major decline in this area.

Food runs the gamut of grasses, herbaceous, and woody plants. Bark, buds, and roots are utilized in the winter. Thick brush piles, farm wood lots, hedges, abandoned farms, ditch banks, rock piles, stubble, dry swamps, brush-grown fences, and old culverts are just a few of the sites used for cover. There are many others.

Cottontails take it easy during the day, spending these hours in grassy forms a short dash from escape cover. They feed in late afternoon and on into the night. With winter, they head for the thickest shelter. Most hunters prefer to hunt in winter when there is a fresh snow covering the ground. Then they can track their prey with ease. Shooting hours are from sunrise to sunset.

SQUIRRELEASTERN AND parts of central Nebraska are the squirrels' stomping grounds. But you'll find them along stream courses throughout the state. Only a sparse population exists in the west due to lack of suitable habitat.

Squirrel distribution is governed by food and cover. High populations occur when food is adjacent, interspersed, or within timber. This is generally the situation in the eastern third of the state.

Look for large trees such as cottonwood, bur oak, elm, box elder, and walnut adjacent to cornfields. Corn is one of the primary foods in late summer and fall. Oak and walnut trees are also a good food source. An abandoned farmstead with a large windbreak near stored corn would be considered an ideal hunting site.

Nests are a sure sign that squirrels are nearby. These are big balls of leaves or twigs. About 14 inches wide, they are spotted in a fork of a limb or the crotch of the tree. Cuttings or the remains of nuts and marks where corn has been dragged are also good signs that squirrels are nearby.

Squirrels are most active during early morning and late afternoon, with morning hours most productive. Fall is a good time to hunt since the bushytails are in the open several hours a day collecting and storing food. Some prefer hunting after the leaves have fallen when it is easier to spot targets. Shooting hours are from sunrise to sunset.

PRONGHORN HUNTING is limited to three areas in the panhandle, North Sioux with 300 permits, Box Butte with 400, and Banner, 100. North Sioux consists of parts of Sioux and Dawes counties. It is bordered on the west and north by Wyoming and South Dakota and the east and south by U. S. Highways 385 and 20. Antelope are fairly abundant throughout the North Sioux area.

Box Butte has shown the greatest increase in pronghorns with the western portions supporting the biggest concentrations. The area is bordered by the Wyoming line on the west, U. S. Highway 20 on the north, U. S. Highway 385 and State Highway 87 on the east, and the North Platte River on the south. Portions of Box Butte, Dawes, Morrill, Scotts Bluff, Sheridan, and Sioux counties are included in the unit.

Antelope are found primarily in the central part of the Banner unit. The area includes those parts of Kimball and Banner counties lying north of U. S. Highway 30 and west of State Highway 29.

Pronghorns range over a wide expanse. They are restless animals and will move about throughout the day with no established feeding or sleeping pattern. Antelope stick to open country where they can spot intruders. If undisturbed, they will remain in small herds at this time of year. Older bucks are often "loners".

Season shooting hours are one-half hour before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset.

4 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

HOW-TO

ANTELOPETHE SURE KILL of a big buck after a long and strenuous stalk is the ultimate in hunting enjoyment, especially in the case of the pronghorn. The stalk gives you the chance to be selective, assures a clean kill, and prevents running which always affects the taste of game. Of course, long or random herd shooting are often easier and quicker, but leave a lot to be desired in sport.

The selective hunter "glasses" the terrain for the telltale white rump patch of an older buck that stays away from the rest of the herd. Then he moves in. It's almost impossible to stalk herds.

In stalking, remember the pronghorn's defenses—keen eyesight and flat terrain. He'll spot you long before you see him if you don't take advantage of every bit of cover. You need not be too concerned about his scenting ability unless you're close.

Work close enough so that the first bullet counts. A good rule of thumb is to be able to distinguish whether your target is a buck or doe without scope or binoculars. If you want both trophy and meat, aim for the chest or lower neck of a standing animal.

Use a gun that is neither too heavy nor too long when stalking. Make sure that it has plenty of knockdown power. Law requires that a gun must deliver 900 foot-pounds of energy at 100 yards. Weapons having a flat trajectory and high energy are recommended.

COTTONTAILLOOK FOR COVER, not cottontails, and more often than not, you'll come home with your share of rabbits. And at this time of year, that cover is edge, a grassy area near a hedgerow, cornfield, rock pile, etc., where the prey can dash to safety.

Eager hunters make the mistake of moving too fast and walk right by game. Hunt slowly and stop frequently. Walk through various cover areas that you know will harbor rabbits. Kick brush piles, investigate around abandoned buildings, work the weed patches, and be ready for the rabbit to break. If you miss on the first shot, select a stand and wait. The cottontail will eventually return.

The amount and types of cover will decline with the advent of winter, giving you a chance to concentrate your hunting. Many prefer to wait for the first snow before going afield. Then they can easily follow the rabbit's telltale tracks to his lair.

Dogs can add a lot to the hunt, not only in finding game, but retrieving it as well. Breeds like the beagle and bassett are top rabbit dogs and have proved their value many times.

Shotguns continue to be the most popular gun used here. Hunters with a steady hand and a good eye, however, would insist that the .22 is far better. The range of shotguns used varies from the 12 gauge to the 410. Either a No. 6 or IVz shot size is preferred.

SQUIRRELSQUIRREL HUNTING is not for the heavy-footed or impatient gunner. To bag bushytails, you must stalk quietly and wait for shots.

Your target has a well-developed sense of hearing, and once he picks up any foreign noises, he heads for the tree top and cover. Nor does he leave anything to be desired when it comes to spotting outsiders. Ears, eyes, and cover are his best defenses.

When hunting, move quietly from point to point. Remain quiet and motionless at each stand for several moments before advancing. Plan your movements beforehand, selecting stands that offer good visibility.

Scan the tops of trees for a bit of fur or an unnatural bump. Wait for it to move, and you have the beginnings of a stew. Though his eyes are sharp, the squirrel may not detect a still hunter in the shadows. The bushytail is curious. If you remain quiet once you've taken a stand, he may come out to see if the coast is clear. If the squirrel is hiding from you, throw a stick on the opposite side of the tree. He will swing over to hide from the new disturbance and becomes an easy target.

The .22 caliber rifle is the squirrel hunter's stand-by. All guns are legal, however, and even handguns are brought into play.

SEPTEMBER, 1961 5

FIELD CARE

FIELD CARE is as important as any other phase of the hunt. To assure good meat, dress the carcass immediately following the kill.

Hot weather, the kind you'll probably be experiencing during the pronghorn season, can ruin the animal's flesh in short order. Remember first to tag your animal, then bleed and dress the carcass. When gutting, pay special attention to the gall bladder when removing the liver. And when cutting and handling the carcass, be sure that the easily-loosened hair does not touch the flesh. Tainting will result. Don't haul the pronghorn on the car fender or in the trunk. Use a car-top carrier or place the carcass in the back seat of your car. Both assure that there will be plenty of air circulating to cool the body.

Squirrel and rabbit field-care procedures are relatively easy. If you are concerned about tularemia when dressing rabbits, use rubber gloves. The best bet is to avoid shooting any animals that look sick or refuse to run. Actually, the incidence of tularemia is very low here and should be of little concern, especially when cold weather sets in.

6 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

RABBIT SQUIRREL ANTELOPE RECIPES

Rabbit BurgersCut all meat off the bones, grind, mixing one-third ground pork to one part rabbit, shape into patties, and fry.—Mrs. Charles Havlicek, DuBois.

Rabbit, Hunters Style 3 or 4 pounds of rabbit 3 tablespoons butter 2 tablespoons olive oil 1 stalk celery, chopped 1 carrot, chopped 1 medium onion, chopped 1 teaspoon chopped parsley 2 tablespoons salt % cup dry sherry 1 tablespoon tomato paste salt and pepper to tasteClean rabbits) and cut into serving pieces. Place in deep dish, cover with cold water. Add 2 tablespoons salt and marinate for 4 hours. Dry with absorbent paper.

Melt butter and olive oil in hot^ skillet. Brown rabbit on all sides (about 10 minutes). Lower flame; add all chopped vegetables, salt and pepper to taste. Cover. Simmer about 10 minutes. Blend tomato paste and sherry; add gradually, stirring frequently to prevent burning. Cover, simmer over low flame about 45 minutes or until rabbit is tender. If necessary, add a small quantity of water to make additional gravy. Serve very hot with boiled rice, serves 4 to 6.—Mrs. Gus Qualtrocchi, Lincoln.

Smothered Rabbit 2 rabbits 1 teaspoon salt Vs teaspoon pepper Dash of paprika Is cup flour *4 cup drippings M to \z cup sliced onion 1 sprig parsley 1 cup top milk or light creamFor older game, cut in serving pieces. Dredge in seasoned flour and brown well in hot fat in fryer or Dutch oven. Scatter onion and minced parsley over pieces, add milk or cream, cover tightly and simmer over low heat or in slow oven (300°F) for 1 to IY2 hours or till tender. Thicken cream drippings if too thin.

Remove to plate, pour gravy over pieces, sprinkle with paprika. Serve with rice, beets or carrots, coleslaw, hot rolls.

Nebraska RabbitSalt and pepper serving pieces. Brown on all sides in butter, then place in covered baking pan. Add to remaining butter Vz teaspoon nutmeg, Vz teaspoon grated horseradish, Stir well and pour over rabbit, add \'z cup water. Bake at 350°F for 1 hour. Remove, make gravy with drippings.

Squirrel SupremeWash and dry cleaned squirrels. Cut into serving pieces. Melt V4 pound or more butter in large frying pan. Brown, don't cook, squirrel. Remove to deep-cooking paa, and brown 2 sliced onions in remaining butter in frying pan. Cover squirrel in pan with melted butter and onions. Add water to nearly cover meat, 3 tablespoons vinegar, pinch thyme, salt and pepper to taste. Cover pan, place in &50°F oven for one hour. Remove, add 18 to 20 prunes to remaining water. Reduce oven to 325°F, bake 45 minutes. Meanwhile mix IY2 tablespoons flour to 1 cup cold water, stir out lumps. Remove squirrels and prunes. Add flour and water to pan, stir over medium heat until gravy thickens.

Broiled Squirrel l young squirrel 1 teaspoon salt l/& teaspoon pepper melted butter for bastingCut squirrel In half and rub with salt and pepper. Brush with butter and broil. Baste and turn meat occasionally until well browned. Total time, about 45 minutes.

Fricasseed Squirrel 1 squirrel, cut in pieces teaspoon salt i/e teaspoon pepper Yz cup flour 3 slices chopped bacon tablespoon chopped onion teaspoons lemon juice cup waterRub pieces with salt and pepper and roll in flour. Pan fry with chopped bacon for 30 minutes. Add onion, lemon juice, and water and cover tightly. Cook slowly for IV2 hours.

Combine, put meat in glass or crockery bowl and cover with marinade. Cover, refrigerate for 10 to 12 hours. Remove meat, drain, and cook as desired.

Antelope Stew 2 pounds breast or shoulder 4 cups boiling water 2 teaspoons salt lU teaspoon pepper 4 medium potatoes, sliced 4 carrots, diced 2 turnips, diced 4 onions, dicedCut meat in Irinch cubes. Roll in flour if desired and brown in small amount of fat in heavy skillet or kettle. Add water and seasonings. Cover and simmer 2 to 3 hours. Add diced vegetables and cook till tender. Thicken juices with flour for gravy.

Broiled SteaksCut steaks % to 1 inch thick. Broil 2 to 3 inches from heat, Season after broiled.

Pan-Broiled SteaksMeat V2 to 1 inch thick. Preheated skillet rubbed with a little fat. No water, do not cover. Turn occasionally. Allow 15 to 20 minutes. Season, serve.

SEPTEMBER, 1961 7

LEGISLATIVE Resume...

THE 1961 SESSION of the Nebraska Legislature included in its agenda several measures of interest to the outdoorsmen. Some passed, some were heavily amended, and some fell by the wayside. All in all, the 1961 session produced significant gains with a few setbacks.

Here are the main recreation measures that were adopted, including the number of the bill, the principal introducer, and a brief resume of the new subject matter.

L.B. 27 — Judiciary Committee—Provides that Game Commission enforcement officers, formerly named in the statutes as "Game Wardens" will be called "Conservation Officers''. L.B. 104 — Senator Syas — Provides for several changes in the game code: Minnow seines must be one-fourth-inch square mesh, while retaining the maximum over-all dimensions of 20 feet in length and 4 feet in depth. Private fish culturist permits will only be issued to persons who have control of artificial bodies of water designed for the purpose of fish culture. Reports from licensed game breeders are now due July 1 and January 1 rather than quarterly. The Commission is authorized to enter into reciprocal agreements with other states bordering on the Missouri River as regards to recognition of licenses, permits, and game laws of the agreeing states. Private pond owners, when authorized by the Game Commission, may remove fish from their ponds by means other than hook and line and in any quantity, when such removal is necessary for proper fish management. Restriction on hunting species other than deer and antelope in the national forests in Nebraska have been removed. These areas will be open 8 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA for general hunting when the hunting seasons

are otherwise open in the national forests.

L.B. 116 —Senator Syas — Clarifies and harmonizes

the laws regarding boating. It provides

standards for proving intoxication while operating a boat as well as penalties for such an

offense.

L.B. 117 — Senator Syas — Authorizes the Game

Commission to issue permits and establish seasons and regulations for wild turkey hunting.

Permits will cost $5 for residents, $15 for non-residents.

L.B. 199 — Senator Nelson — Provides that persons

who have beaver damage on their property

may notify the Game Commission by registered

or certified mail of such damage. If the damage complaint is valid, the Game Commission

shall either remove the beaver within 30 days

or issue a permit valid for 90 days authorizing

the complainant to destroy the beaver. Beaver

pelts taken under such a permit may not be sold

or used unless the permittee also possessess a

current and valid trapping permit. (Emergency)

L.B. 208 — Senator Syas — Provides the means to

finance the state park program with a .30 mill

levy. It also limits the amount that may be

spent on the Platte Valley Park System. The

law will become effective with the 1962 assessments. Income will be available in December,

1962.

L.B. 363 — Senator Moulton — Requires and provides for licensing of commercial put-and-take

fishing establishments, providing that when

such establishments are so licensed, no permit

is necessary to fish therein. (Emergency)

L.B. 498 — Senator Rasmussen — Provides that

when specific habitat improvements for game

birds or animals are made by landowners or

tenants who are in actual and continuous residence on farms or ranches, and when these

habitat improvements are above and beyond

land use practices pursued for agricultural purposes, and when these habitat improvements

meet the standards and requirements prescribed

and established by the Game Commission, a

small-game hunting permit shall be issued

without cost to the landowner or tenant upon

proper application to the Game Commission.

L.B. 502 —Senator Vosoba —Provides that full-time Conservation Officers shall be officers of

the state with the powers of sheriffs or constables with authority to make general arrests,

work traffic, etc., when so requested by other

law enforcement officers in a specific emergency situation.

L.B. 635 —Senator Knight — Provides $10,000 per

month in matching grants of state gasoline tax

funds to counties which apply for funds to build

or improve access roads to state park areas or

state special use areas where motorboating is

possible and permissible. It also provides that

gasoline used in motorboats shall not be eligible

for gasoline tax refunds. (Emergency)

L.B. 654 — Senator Brandt — Permits the Game

Commission to issue concession agreements on

state park areas for periods not exceeding 20

years. (Emergency)

for general hunting when the hunting seasons

are otherwise open in the national forests.

L.B. 116 —Senator Syas — Clarifies and harmonizes

the laws regarding boating. It provides

standards for proving intoxication while operating a boat as well as penalties for such an

offense.

L.B. 117 — Senator Syas — Authorizes the Game

Commission to issue permits and establish seasons and regulations for wild turkey hunting.

Permits will cost $5 for residents, $15 for non-residents.

L.B. 199 — Senator Nelson — Provides that persons

who have beaver damage on their property

may notify the Game Commission by registered

or certified mail of such damage. If the damage complaint is valid, the Game Commission

shall either remove the beaver within 30 days

or issue a permit valid for 90 days authorizing

the complainant to destroy the beaver. Beaver

pelts taken under such a permit may not be sold

or used unless the permittee also possessess a

current and valid trapping permit. (Emergency)

L.B. 208 — Senator Syas — Provides the means to

finance the state park program with a .30 mill

levy. It also limits the amount that may be

spent on the Platte Valley Park System. The

law will become effective with the 1962 assessments. Income will be available in December,

1962.

L.B. 363 — Senator Moulton — Requires and provides for licensing of commercial put-and-take

fishing establishments, providing that when

such establishments are so licensed, no permit

is necessary to fish therein. (Emergency)

L.B. 498 — Senator Rasmussen — Provides that

when specific habitat improvements for game

birds or animals are made by landowners or

tenants who are in actual and continuous residence on farms or ranches, and when these

habitat improvements are above and beyond

land use practices pursued for agricultural purposes, and when these habitat improvements

meet the standards and requirements prescribed

and established by the Game Commission, a

small-game hunting permit shall be issued

without cost to the landowner or tenant upon

proper application to the Game Commission.

L.B. 502 —Senator Vosoba —Provides that full-time Conservation Officers shall be officers of

the state with the powers of sheriffs or constables with authority to make general arrests,

work traffic, etc., when so requested by other

law enforcement officers in a specific emergency situation.

L.B. 635 —Senator Knight — Provides $10,000 per

month in matching grants of state gasoline tax

funds to counties which apply for funds to build

or improve access roads to state park areas or

state special use areas where motorboating is

possible and permissible. It also provides that

gasoline used in motorboats shall not be eligible

for gasoline tax refunds. (Emergency)

L.B. 654 — Senator Brandt — Permits the Game

Commission to issue concession agreements on

state park areas for periods not exceeding 20

years. (Emergency)

Laws followed by the word emergency were in effect upon the signature of the Governor. Other laws listed become effective on the ninth of October, 1961, except that the levy for state park development (L.B. 208) will become, in practice, effective in December of 1962.

Measures covering hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation are a product of legislative action by the Nebraska Unicameral Legislature, and of Game, Forestation and Parks Commission regulation enacted under the authority provided by the Legislature or the federal government. Outdoorsmen should become familiar with all. THE END

SEPTEMBER, 1961 9

BLACK CHAMPION

by Wayne Tiller Superb scenting powers and hardiness make the Lab "the dog" among dogsWHETHER SCENTING eagerly on the trail of a pheasant or hitting the water boldly to retrieve a downed mallard, the Labrador retriever shows that special eagerness and hardiness that makes him a dog among dogs. Once you see him in action, you'll realize he's built for the hunt.

His ability to scent out game is almost unbelievable. Big going on land, he's a master in water. Whether running or swimming, he moves swiftly and surely toward his prey. Intelligent, he needs only the slightest of hand signals to put him on course. His short, dense coat sheds water or brush with equal ease. Though rugged, he's the kind of companion you can depend on, afield or at home.

Such a display of eagerness, versatility, and intellect has won the Labrador the praise and confidence of hundreds of Nebraska sportsmen. And it's no wonder. He's the perfect dog for the variety of game hunted here.

To really appreciate the Labrador, you have to know his background, where he originated, how long he's been used as a hunter, and how his field trial and bench records compare to those of similar breeds.

The "Lab" did not originate in Labrador as the name implies, but in Newfoundland. At least, that's the popular opinion. And even the possibility of his ancestors originating there is doubted by some canine historians. They contend that the breed was introduced to that land when the fishermen of Devon, England, invaded the shores of Newfoundland, Britain's oldest colony, in the 16th century. This information and the possibility of the retriever originating in England is not greatly accepted although it is entirely possible.

It has definitely been established, however, that even in the 17th century, Portuguese fishermen frequenting Newfoundland shores were accompanied by dogs resembling the Labrador. The canine salts earned their keep. The powerful swimming dog retrieved dropped cod, broken nets, or other tackle from the cold water that was unbearable to man. This same dog, again using his fabulous scenting ability, helped shore parties hunt wild fowl.

Even though a few of these hardy dogs had seen Labrador, their only connection with that country is that the fishing boats bringing them to England often carried catches of salted cod caught on the banks off that bleak and desolate shore. They were known as St. John's dogs or St. John's water dogs.

In the early 1800's, the third Earl of Malmesbury

realized the Lab's hunting potential when he saw

10

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

one of these heavy black dogs on a fishing boat in

the English port of Poole. The find so inspired him

that he immediately started buying the dogs from

fishermen sailing between Newfoundland and Poole

Harbor.

one of these heavy black dogs on a fishing boat in

the English port of Poole. The find so inspired him

that he immediately started buying the dogs from

fishermen sailing between Newfoundland and Poole

Harbor.

Other writings from that era indicate that it was a common practice for sailors to sell their canine shipmates in English ports. Although many breeders crossed their new dogs with other retrievers, like the flat-coated and curly-coated varieties, the purebred Labradors of today can be traced to a few of these early importers who through careful breeding maintained the integrity of the strain.

The Earl of Malmesbury was one of these early fanciers that preserved the Labrador breed. He wrote in 1887, "We always call mine Labrador dogs and I have kept the breed as pure as I could from the first I had from Poole ." His letter also indicates a possible origin of the name.

The Labrador's ability to scent out game under the most adverse conditions was recognized at an early date. Colonel Hawker, an English sportsman and author, wrote in 1830 ". . . their discrimination of scent in following a wounded pheasant through a whole covert full of game, or a pinioned wild fowl through a furze break or warren of rabbits, appears almost impossible."

Probably the longest traceable bloodlines in the records of this breed belonged to A. C. Butter's Peter of Faskally, and Major Portal's Flapper. Their pedigrees go back as far as 1878. It was not long after the pedigrees of these two Labradors were announced that English fanciers of the breed, desiring to stop inbreeding, drew the standards of the hunter to discourage crossing with other retrievers of the day.

It was not until 1903 that the Labrador was recognized by the English Kennel Club as a special breed. Three years later the Honorable A. Holland Hibert ran Mundin Single, the first Lab ever to compete at field trials or on the bench. Up to this time the flat-coated retriever had held undaunted supremacy over the curly-coats; but from this time on the Lab gradually established the extraordinary record he now holds in British dogdom.

The Labrador didn't take hold in America until the late 1920's. The first licensed trial here was held at Glenmere, Chester, Orange County, New York, in 1931. Sixteen dogs were entered in the "open-all-age" event. The winner of the stake was Carl of Boghurst, owned by Mrs. Marshall Field.

In like manner, when the first all-breed field trial in this country was held at Strongs Neck, East Setauket, New York, on December 29, 1934, in which all retriever breeds were eligible, the Labrador copped first, second, and third honors.

The late J. F. Carlisle, owner of the Wingan Kennels on Long Island, was one of the earliest serious importers and breeders. In 1933, he brought in English stock that has done much to place the Labrador where he stands (continued on page 24)

A Friend of a Friend

Suburban striper leaves treadmill for country and gal striperTHERE IT WAS, the biggest, funniest looking nut he had ever seen. At least, he thought it was a nut. It fell kerplunk, straight down the hole to his home and on down the lateral hallway. The big thing rolled into his new, grass-lined master bedroom where he'd been enjoying his usual latemorning snooze.

Now a 13-striped ground squirrel isn't one to ask where or how he comes by his next meal, but this was too much. Imagine, breakfast in bed, and without even so much as lifting a paw.

Well he did lift a paw, to wrestle with the big white nut. And he crunched down with his chisel-sharp teeth on its pock-marked surface.

He crunched and crunched. And each time he crunched, the white nut moved away, until he was out of bed, into the hallway, and finally right at the door. And he never got so much as a taste.

Then all went black. Not because he was dying of hunger or anything like that, but because someone had turned off the lights. That someone was a nose and a big angry eye staring down the hole. The striper dove for his bedroom. The eye disappeared, and in its place came a hand. After considerable groping and squeezing, it snatched that nut away.

The 13-striper's heart beat like a hammer. Ten times faster than its normal 250 beats a minute.

Finally, ever so carefully, he eased up the hallway. There was no doubt that he was scared, but he was curious, too, and had to see what caused all of the ruckus. He found the entrance hall a mess. All the work he'd done before to carry away the dirt and hide it in the grass around his home was in vain. Well back to the old gnawing board.

Calling upon all of his courage, he darted up the entranceway tunnel and stood rigid as a golf tee at the edge of the door. He didn't move a muscle, blending in with the grass around him. His heart was beating pretty fast again, and his black button eyes flitted this way and that, taking in all the green lawn that rolled out ahead of him.

Down the hill aways he spotted the man who had swiped his nut. The guy was mumbling something about how sand traps were bad enough, but squirrel holes were sheer treachery.

"Fore!"

Another white nut, just like the one that had rolled into the striper's home, went whistling over his head. This was quite a day. Even the sky rained nuts. And over there, on a lush green circle with a flag in the middle, another man was ready to pounce on another one of those morsels.

He wasn't really pouncing. He was down on his knees, looking from the nut to the hole where the stick had been, figuring and measuring and rubbing his jaw. Then the man got up, flicked a leaf out of the way, came back, stood rigid as a striper, and after the longest time, hit the nut with a pole and watched it roll in the hole.

Boy, this was too much. Maybe it was the heat. Or a bad dream and the striper was still asleep. Either he or those guys chasing the little white nuts needed a long rest in the country.

That's it. He would go to the country, away from all of the hubbub and white nuts in suburbia. Give him the clean air, the wide-open spaces, and the farmer's corn crib. He knew a friend who knew a friend who made the trip earlier. The striper would introduce himself and his worries would be over.

Without so much as packing a bag, he headed

for the great outdoors, a quarter mile away. The

striper was so enraptured by the call of the country

that he tripped over a divot before he had traveled

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

10 feet. And halfway across the fairway, he was

shelled by another nut. That really sent him flying.

10 feet. And halfway across the fairway, he was

shelled by another nut. That really sent him flying.

Then there was the ground keeper's cat. The striper almost walked right over the purring ball of fur. He was sound asleep after a meal of mice.

Get a hold of yourself boy, he scolded himself. There are cats and dogs, and coyotes and foxes, and weasels and hawks and snakes who would dearly love to make a stew of you. But he would have to move along if he expected to get to the country before bed time. Early to bed, late to rise had been the striper's rule. And now he didn't even have a bed to sleep in. But fortunately, the striper did have a friend of a friend.

He didn't leave suburbia penniless. The striper had the good sense to fill his cheek pouches with seeds. At noon he paused for a quick meal. Stretching his seven inches bolt upright, he stood like a sun dial with his tail pointing at high noon. Lunch over, the ground squirrel proceeded on his way and eventually made it to the country. After checking a couple of homes and a stop at the corn crib for a refresher, he found where the city striper lived.

The ground squirrel had his little speech all prepared when he knocked at the door. How he had dropped by for just a minute and . . . No, he really couldn't stay because he had a lot of folks to visit and . . . Well, yes, he was hungry, and it was probably late and the motels were full.

But the striper forgot all of this when a LADY answered. She was the friend of the friend. This would hardly do. But as it turned out, she had some friends, too, and one of them was more than happy to take care of a visiting fireman.

His bed wasn't too comfortable. Too much grass and didn't have much support to it. But the striper wasn't about to complain. One can't look a gift house in the mouth. Before the sun went down, he was sound asleep and dreaming of that friend of a friend.

The ground squirrel got up the next morning, late as usual, but ready to scout around for a lot where he could dig himself a home. One thing about country life, he discovered, taxes weren't too high and food was cheap.

He looked at this site and that, considering the view of one and wondering about the neighborhood of another. Finally he found one on a slight rise. The grass wasn't so high that he couldn't snoop on the folks next door.

This could be my honeymoon cottage he thought, as he dug away. Pretty soon there would be the patter of little feet, maybe 11 or 13 little patters. But that was jumping the gun. First, he had to get the house built.

The striper had lunch on the run—between the deepening tunnel and the grass beyond where he scattered the dirt. By late afternoon the hole was deep enough to bed down in, and soon after dinner he was sound asleep.

For the next week or so the striper worked away on his home. He added a new (continued on page 24)

HISTORY ON A HIDE

by J. Greg Smith

An old ranch house at Agate holds

the Sioux side of Custer Battle

by J. Greg Smith

An old ranch house at Agate holds

the Sioux side of Custer Battle

IT WAS BUT A small dust cloud far out to the southeast along the ridge across the Little Big Horn. But it was coming fast, no longer dust alone, but a forked flag at the head of a long thin line of cavalrymen aimed squarely at the great Indian encampment.

Bravely they came, five companies, 197 troopers, old campaigners and those yet to taste blood and battle. Boldly they came, into the hornet's nest of Cheyenne and Sioux. The medicine man had visioned their coming. Now they were here, driving down the breaks to cross the river and attack the village.

But they never made the Little Big Horn. From it, to their left and right, a bronzed horde swarmed over the 197, and the cavalrymen broke for the ridge to escape this unexpected fury. Then even that route was blocked when still more Indians appeared on its summit.

In that moment day became night. And the mushrooming dust cloud that blacked out the hot June sun was a shroud to hide the dying. The Indians pressed in on those snared on the ridge, then crushed them under crashing hoofs. Only a few remained, running toward the river so far away. Then they were down, and suddenly there were no more to kill.

It was over, done, an eternity that lasted but a few minutes. General George Armstrong Custer was dead, his body somewhere within the bloody pile on the ridge. Below, scattered here and there in pitiful little clumps, were the rest of his men, all dead. And the story of their battle, the why's of Custer's folly were sealed on the lips of torn bodies now bloating under a blazing prairie sun.

Only the Indians could tell what had happened on this fateful day in 1876. Nor would they tell the full story until years later when all of the old hates had dulled. Two warriors chose to relate the battle in their own way, telling it in pictures to a man they could trust, Captain James H. Cook. In 1909, 33 years after they had counted coup on Custer's Seventh Cavalry, they came to the famed scout's ranch at Agate and through the summer created a pictograph on a cowhide that has become a cherished memento and a graphic record of their greatest victory.

Captain Cook is dead. So are the warriors who painted the pictograph. But the hide remains. Fading and delicately brittle, it is attached to the ceiling of the historic old ranch house that has become a repository of priceless relics of Nebraska's once untamed frontier.

Cook's son, Harold, now operates the big ranch. The 72-year-old rancher and world-farned consulting geologist was only a small boy when the pictograph was made.

The ranch was a friendly haven to countless Sioux who were confined at the Red Cloud agency at Fort Robinson. The famed Chief Red Cloud was a close friend of the elder Cook, and was there when the pictograph was made.

According to the Sioux and their pictograph, Custer never made a "last stand". Instead, they say that the troops were thrown in complete panic when the Indians struck, and in less than five minutes the battle was over. Custer "was one of the first soldiers shot down," badly wounded. Knife Chief, a Sioux sub-chief, threw a blanket over "Yellow Hair," hoping to take him prisoner. But he never succeeded, for an Indian woman killed the General with her butcher knife before the warrior returned.

Red Cloud, as chief of all the Sioux, is represented on the hide by a figure with a red cloud over his head. His Indian symbol is also shown. Indians that participated in the battle are shown in the designs on the tepees. Actually, every drawing is representational of some person or event of the fight. Oglala, Brule, Hunkapapa, Sans Arc, and Minneconjou Sioux and Northern and Southern Cheyennes were there. The number of braves that overwhelmed the Seventh is estimated at well above 1,000.

Cook has forgotten the meaning of some of the drawings. But he remembers most. Cavalry horses, for example, could easily outrun the Indian ponies and were therefore shown with long legs. The trooper with a pistol to his head is on such a horse. Even 33 years later, the Sioux could not forget this man. He was known to them as Lieutenant Doctor. The man, Lieutenant Lord, was a doctor with the Seventh, and committed suicide after he had almost made good his escape.

As in most Indian pictographs, only the enemy is shown dead or being killed. Of course, in the Custer battle, this was pretty much the case. Only eight Indians died at the Little Big Horn.

After reading the various accounts of the battle, it is almost possible to "read in" meaning to some of the drawings. The figures in the center of the tepee ring might represent Reno's forces "who fell into camp" as Sitting Bull had visioned. Reno along with Benteen were the commanders of the Seventh's other units in the over-all campaign. Both were accused of failing Yellow Hair when the chips were down. The two rows of troopers might suggest that Custer was able to form skirmish lines. The circle with the blocks around it might be the spot where the last soldiers fell.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn will never be forgotten, in part because of a fading pictograph on the ceiling of an old ranch house at Agate, Nebraska. Thanks to James Cook and his son, it remains still to relate the story that has become an immortal legend of the West.

THE END

HUNTING DO's

PRESTIDIGITATING

by Marie LarsonWOMEN MAY deduct five years from their true age or even subtract 10 pounds from their actual weight, but never, if as a hostess, they serve a delectable cake and a guest asks for the recipe would they dream of writing vinegar if the recipe called for molasses. Why, then, is it that a man who is using minnows for bait and having good luck will tell another fisherman that he is using worms?

A wife of a fisherman can only look with wonder upon the man who she has married, believing him to be the soul of integrity. With experience, she may grow to understand this double standard and learn to differentiate between the fisherman and the upright man she took for a husband.

Proud as I am of the skill which my husband possesses in luring bluegills, crappie, and bass to his hook, I must admit that I have experienced much dismay as I realized that this skill is closely tied in with the art of telling lies. Lately this dismay has changed into acceptance of the fact that the majority of men fib as a matter of course when it pertains to fishing.

Early this summer, my husband and I joined the steady stream of cars making their way to the Niobrara and Missouri rivers where good catches of sauger and catfish had been reported. Every accessible bank and boat dock was crowded with men and women who had reached the river before we did. All had staked out claims, We traveled many miles over countless back-country roads before we found an isolated spot.

I baited my line with a shining fish, cast out into

the deep water, and surrendered myself to the serenity of the lapping water and the distant green-covered hills.

My peaceful thoughts were disrupted

by the sound of a car, belching and snorting as it

rattled down the deeply rutted lane. I turned around

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

to see an ancient relic bearing down upon us. With

a final cough the car stopped and an elderly man got

out.

to see an ancient relic bearing down upon us. With

a final cough the car stopped and an elderly man got

out.

"Any luck?" he asked.

"We just got here," answered my husband.

"Hear they've been catching some pike and cats along here," said the man.

Now my husband has a friendly, gregarious sort of nature and is known as a "good Joe" around our home town. I was surprised when he remained silent and sat watching his lines. Being a friendly type, myself, I felt he was being rude so I volunteered the information that we had heard of some good catches made on this part of the river.

The fellow said he'd never fished in these waters before and that he'd driven a good many miles to reach it. Although he'd fished since early morning he hadn't had a bite.

My husband looked up at this and said, "They've been catching some nice cats over on that point." He indicated a spot about a half-mile up the river from our spot.

"Oh?" returned the man, looking at the spot. He lingered a while longer and then went back to his car.

"Who caught fish over there?" I asked innocently after the man had left.

Andy grinned at me and replied "No one. At least as far as I know."

"Then why, in heaven's name, did you say that?" I demanded.

"One thing you'll have to learn. A guy never tells anyone else where he caught his fish. If you come home with a good catch and someone asks you where you caught them, answer, 'on the river.'"

Now the river is many, many miles long and I can understand why no one would divulge a good fishing spot. But to deliberately tell a man that fishing is good on a certain point when you've never been there, nor has anyone else that you know, that's something else.

I kept looking at that point, feeling sorry for the man. But apparently he was a dyed-in-the wool, lie-hardened fisherman, too, because that point stayed as empty as my creel.

Several weeks later we went fishing again. This time we chose a good-sized dam closer to home. Andy hoped to catch some bass. Since it is a pleasure to watch him cast as he flyfishes, I stayed close. Several of his acquaintances were fly fishing, too. Andy kept hooking bluegills. One of the men called to him and asked what he was using for a fly.

"A bee," he answered.

A short man, who couldn't wade out as far as the other two asked, "What did he say he was using?"

"A beetle," answered the first man.

Both opened their fly boxes and changed flies. I knew Andy was using a white moth as the water was covered with small gray white bugs and the fish were jumping. But the first fellow put on a bee and the little man baited a beetle. The ironic part of this exchange was that the little guy caught the only bass that afternoon.

Perhaps I shall never make a good fisherwoman. If someone asks "How's fishing" I give an honest answer. If I have been fortunate enough to have caught some fish, I proudly pull up my stringer and show them. If I'm using worms, I don't say minnows.

Women may alter their age, weight, or measurements, but that's the extent of it. We love to share our hints, short-cuts, and recipes; anything that will add to successful living for our fellow man. If we lied, like fishermen do, we wouldn't have a friend left. Yet the obvious fact remains that men can tell each other such atrocious stories, give each other bum steers, and still remain the best of friends. It would take a fisherman to explain why.

THE END SEPTEMBER, 1961 19

BALLARDS MARSH

by Mary Brashier Waterfowlers needn't worry about targets or access at this top areaA SILVER TRIANGLE rippled through the dusky brown open water of the marsh, at its apex was a muskrat, paddling leisurely. He swam around his lodge, inspecting it closely, then climbed up over the rushes and began to sun himself. Nearby a cattail cut a wide swath through the water, propelled expertly by another muskrat making autumn repairs to his lodge. September was in the bright blue Sand Hills sky, and everywhere across Ballards Marsh were the preparations for winter.

Migrant ducks had been arriving for days now, lingering awhile in this favorite marsh. Northern teal had come in first, fast and low, pushing a white lace of water ahead of their upturned feet as they coasted to a stop. Soon the summer inhabitants—the bluewings, pintails, and coots—became indistinguishable among the new arrivals.

The afternoon wore on, and a young marsh hawk drifted across the deepening sky and made fruitless passes into the meadow. A raccoon waddled down a trail, fished a small dead perch out of the water's edge, and feasted. A coyote floundered wetly on an island of vegetation, and scrambled back to shore. The smell of a sick muskrat could not lure him farther into the treacherous footing of the marsh. Later that night a mink pulled the dying rat off its lodge. A snapping turtle found the carcass and finished the job.

The muskrats and ducks dominate Ballards Marsh

in September. In October come the hunters, for

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

this is a Game Commission marsh, the first public

shooting area officially established in Nebraska back

in 1930. A fine long record of public hunting is now

somewhat obscured by rank vegetative growth at

Ballards. Because of its easy accessibility, however,

the area still plays an important part in the state's

waterfowling picture.

this is a Game Commission marsh, the first public

shooting area officially established in Nebraska back

in 1930. A fine long record of public hunting is now

somewhat obscured by rank vegetative growth at

Ballards. Because of its easy accessibility, however,

the area still plays an important part in the state's

waterfowling picture.

Ballards Marsh is a typical Sand Hills marsh, lying about 20 miles south of Valentine in Cherry County. It is easily reached by U.S. Highway 83 which slashes through the eastern edge of the 1,583-acre area. In addition to offering prime waterfowling and pheasant and grouse hunting, Ballards Marsh has a small but immaculate campground with all facilities. The recreation area plays host to fishermen angling the many Sand Hills lakes in the immediate area.

Almost two-thirds is marsh; sand hills and low meadows make up the remaining portion. A trail leads northwest from the highway to Big Alkali Lake, a Game Commission area noted for both fishing and waterfowling several miles away. Typical Sand Hills country, Ballards Marsh is treeless, except for plantings around the camping area which are not yet big enough to afford extensive shade. The open water covers about 340 acres, with a good fishery potential. Most of the perch and bass now present are undersize.

The marsh is very nearly virgin—ranchers harvest hay crops from the meaHows, and in the fall and spring, cattle graze the fine grasses. But in the summer it is left to the muskrats and ducks.

Pheasants and grouse are afforded excellent cover by the rank grasses, and a sharptail dancing ground is located nearby. Deer come frequently to Ballards, and a myriad assortment of other Sand Hills life.

Here is an excellent study area for those wanting to know Sand Hills marshes, for here is a compact community of mink and coot, muskrat and coyote, ducks and blackbirds, and many, many others. It is a lesson in population dynamics to the true outdoorsman, and an untapped potential to the waterfowler and trapper.

THE END

STOCKING VS ENVIRONMENT

by Dr. Edward C. Kinney West Virginia Conservation CommissionTHE MOST COMMON question asked this time of the year is, "How is your stocking coming along?" When I reply that we have more trout in our hatcheries than ever before and that we shall receive a record amount of trout from the federal hatcheries, the questioners are very pleased.

The public, in general, judge the quality of the state's fish management program by the number of fish that are stocked annually. Most fishery biologists, however, share the almost opposite point of view; that the stockings are regarded as an admission that the management programs have failed. We have failed to maintain favorable aquatic environments which would have made many of the stockings unnecessary.

Some states highly publicize the numbers of fish stocked. They often fail to mention that the millions of fish stocked were smaller than an ordinary book match and that the chances of survival are slim indeed.

Dr. Paul R. Needham, one of the nation's top authorities on trout, recently reviewed many of the scientific reports on the results of trout stocking. He found that the average suvival for stream plants of fingerling trout was 2.5 per cent. In an experiment in Oregon, the cost for each trout which reached adult size was $28.53 per fish.

During 1952 and 1953, we stocked 13,651 marked and tagged smallmouth bass in the Elk River. To date, only seven of these bass have been caught. These seven bass cost about $180 apiece. During 1952 through 1955, New Jersey biologists stocked 16,200 marked fingerling bass in one of their bass streams. Considerable effort was made to locate these bass after their release. The stream was seined, trap netted, and sampled by rotenoning. A thorough creel census was conducted. Through June, 1958, only one was found.

Stocking should be restricted to the following:

1. Interim trout stocking in the mountain waters until the environment can be improved so that natural reproduction will be increased.

2. New lakes.

3. Reclaimed lakes and streams.

4. The introduction of desirable species that are not present in a particular body of water.

Reprinted from the April, 1961 issue of West Virginia Conservation

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

PENNSYLVANIA ... In Snyder County a woodchuck hunter's curiosity was aroused when he saw a cherry tree's branches shaking violently. He approached within 15 yards and spotted a large raccoon in the branches, feeding on the fruit. What the hunter saw next really jarred him. Beneath the tree mature gray fox which was watching the raccoon and every cherry it dropped or shook to the ground.

Though fascinated by the unusual performance, the man eventually turned practical. One shot dropped the fox; another brought the raccoon's cherry picking to a permanent end.

Gripe, Gripe, GripeNEW MEXICO . . . You can't please everybody. The latest complainer had for many years enjoyed hauling in big rainbows from the Chama. Now comes the New Mexico Game Department, lavishly planting 8-to-10-inch rainbows in his favorite stream. The gripe: the middle-size fish are hungrier than the big ones, so they're the ones that get hooked.

He won't even fish the Chama any more. His luck's apparently better on the Pecos.

MISSOURI ... It doesn't pay to defect to Russia, especially if you're a pintail. A pair banded at the Trimble Wildlife Area near Kansas City in March 1955, tried it and ended up dead. By chance or mischance, they took the wrong turn in their migration route and settled down on Russia's side of the Bering Sea. They were shot within two days of each other in May 1959.

Ringneck EscortPENNSYLVANIA . . . Farmers know that the habits of birds and animals change with the seasons, but a sociable ringneck thoroughly baffled a Union County man recently. Stray dogs had been causing him trouble this spring. When four of them appeared, the farmer started after them with a gun. He had not walked far when he noticed a ringneck rooster, about two corn rows distant, keeping pace with him. He hurried through the stubble field, into another, and continued along a woods, the ringneck going right along. Not able to catch up with the dogs, the farmer returned to the house, still in company of the cock. About 75 feet from the barn the bird stopped, watched the man until he entered the house, then turned and walked away.

Who Coos?IOWA . . . Not to dispute the experts on the subject of dove cooing, that only the bachelor birds do it, John Garwood of Marshalltown has had a pair of doves nesting in his bushes for several years, and the pa and ma have always seemed quite happy and have been doing a heck of a lot of cooing from the same shrub. Could be a family problem, he's never gone into it that far.

Number, Please?OHIO ... A woman about to make a telephone call opened the door of a phone booth to find it already occupied by a fighting-mad young muskrat. Slamming the door shut, she reported the situation, from another phone. A game-management agent captured the half-grown muskrat, surely experiencing one of life's darkest moments right then, and released him in a nearby river. Muskrats often venture from home when litters crowd their dens, but this unfortunate just couldn't make the right connection in the outside world.

He Got the PointNEW MEXICO ... The list was long, and growing—shooting in the front yard of a farm house, nonpossession of a hunting permit, shooting a protected migratory songbird. The officer was stern, the hunter was shifting his feet, the officer's hunting dog was snooping. Suddenly the dog got a message—and froze in a perfect point on the fender of the hunter's pick-up truck with his nose just a few inches from the spare tire. The warden asked if the man had been taking a few off-season quail. What could the hapless hunter do? He volunteered, "ONE."

The officer found eight in the spare tire, and hustled the thoroughly subdued violator off to court.

Compact CompactNORTH DAKOTA ... A district game warden was told this story by a very badly shaken motorist. The man had been cruising along in his Austin-Healy sports convertible, with the top down. A big whitetail buck loomed up in front of him before he could swerve. The sports car was so low that the impact rolled the deer over the hood and on top of the driver. Apparently the folded fabric top broke the deer's fall and the buck slid off the back of the car and kept going. The warden found only one small dent in the car where the buck's hoof had ticked the hood before he landed on the driver.

BLACK CHAMPION

(continued from page 10)today. Averill Harriman is another who has done much for the breed.

Michael of Glenmere, owned by Jerry Angle of York, Nebraska, won the first American field and bench championship in 1941. Bing Grunwald of Omaha maintained Nebraska Labrador prestige when he was awarded the coveted Martin Hogan award for his contributions to the furtherance of retriever work with his Labradors.

Grunwald's Boleys Tar Baby is one of the more recent field champions to draw the envy of Labrador-conscious Nebraska sportsmen. They are also watching John Van Bloom's 18-month-old bench champion, Dutchmoors Etoin Shrdlu known as "Pi". Many observers see this Lincolnite's Calypso Clipper as a future dual champion.

What do they see in these and other champions? The dog is strongly-built, very active, fairly wide over the loins, and muscular in the hind quarters. The coat, generally black, is close, short, dense, and free from feather. The skull is wide with a pronounced brow and the jaws are long and powerful. The ears are set low, hung rather far back close to the head, and the medium-sized eyes express intelligence and good temper. The tail is thick toward the base, tapering toward the tip, and of medium length, giving the "otter" tail appearance. The legs are straight from shoulder to ground with hocks well bent. Weighing about 55 to 75 pounds in top condition, the Labrador will measure 21V2 to 23 V2 inches at the shoulder.

You'll see such dogs afield this fall, proud, eager Labradors willing to give their all for their masters. They'll retrieve many a wounded bird that might have been lost, scent out pheasants that the hunter would never see. If you're a serious sportsman you'll want such a companion.

THE ENDCLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cenls a word: minimum order $2.50 FOR SALE: Registered Brittany spaniel pups. Vaccinated. Few eight months old. Just right for hunting this fall. J. P. Lannan, West Point, Nebr. MODERN TAXIDERMY: Game heads, animals, birds, fish, rugs, and novelties. Otto Borcherdt, Taxidermist, 2247 South 17th, Lincoln, Nebraska. GA 3-0487. LABRADOR PUPPIES for sale. Whelped Memorial Day. Excellent blood lines. AKC, FDSD. Males $60, females $50. R. C. Pancoast, 328 Downing, Fremont, Nebraska. Phone 721-3802. AKC BLACK LABRADORS. Pups. Started dogs. Top hunters, and field-trial prospects. Litter of Brittanys bred to hunt. Kewanee Retrievers, Valentine, Nebraska. Phone 26 W3. MOUNTING DEER or antelope head, $25. Mounting average size black bear rug, $40. Mounting coyote or bobcat rug, $15-$18. W. H. Strange, Nebraska City, Nebraska. VIZSLA pointer-retrievers puppies and started dogs by field-trial winners. AKC, FDSB. Graff's Weedy Creek Kennels, Route No. 3, Highway 15, Seward, Nebraska. Phone 8647. FOR SALE: Registered Brittany Spaniel pups. Whelped July 27. Champion bloodlines and pedigree. Albert Smykla, 6920 North 56 Street, Omaha, Nebraska.FRIEND OF A FRIEND

(continued from page 12)room here, lengthened the hallway there. And on occasion he had enough time to get down to the corn crib and jaw with the boys.

The striper hadn't seen much of his female friend. He was more concerned about laying in food to nibble on through the winter and when he woke up after the long sleep in April. Then one afternoon in early September he saw her. Boy was she fat. Food pickings for the fall and winter siesta were apparently easy. Hardly one of the boys lifted an eye as she waddled by. She couldn't care less, for like the rest, she was concerned about one thing—food.

His days were one mad round of feasting. The striper would start off with an entree of grubs. This was followed by a tossed salad of roots and leaves. Then came the main course—grasshoppers, wire-worms, cutworms, caterpillars, and crickets topped with ants and beetles.

So much gorging would make anyone snoozy. The striper couldn't fight the yawns any longer. He waddled over to his home, squeezed down the tunnel, checked his food supply, mustered all of his energy to plug the doorway, then rolled up in a ball in his cozy grass-lined bed and went to sleep for the winter.

Just before he dozed off into slumberland, the striper remembered his friend of a friend when she wasn't so fat. Well, he yawned, she won't be fat when she wakes up in April. Then I'll go knock on her door and . . . but then he was asleep. He had a kind of a smile on his mouth.

THE ENDBIG HILL CAMP

offering GOOSE, DUCK, UPLAND, and BIG GAME HUNTING with experienced guides. Outstanding fall fishing. Modern accommodations, lodge overlooking Missouri. For reservations, write or call Jon Schulke—Guide and Outfitter Big Hill Camp Ponca, Nebraska RATES PER DAY GUIDES Waterfowl— per hunter $10.00 Upland— per hunter $10.00 Deer— per hunter $10.00 Small Game— per party $12.50 Fishing— per party $12.50 LODGING Cabin (hunters) ..$7.00 Cabin with boat (anglers) $10.00 American Plan (meals, lodging, game processing, freezing $10.00

SPEAK UP

Send your questions to "Speak Up", OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, State Capitol, Lincoln 9, Nebr. First Aid for Fishing Hook"While on a family fishing trip recently, my daughter Sharon cast her line into the wind only to have it blown back and the hook imbedded in her neck. We were 40 miles from the nearest town, 60 from the nearest doctor, and some immediate first aid was demanded.

"Knowing that the skin of the neck is loose and stretches easily, I cut a wedge out of a cork fishing float. Then I held the wedge against the skin where the barb was hidden below the skin, and pushed the hook into the cork. I could then cut the barb off and back the hook out of the wound. Since the skin is not stretched in this procedure, there is little pain compared to pushing the hook on through. A handkerchief could have been substituted for the float.

"We got Sharon to medical attention 60 miles away then, and the doctor who examined her later said we did the right thing. I hope no one who reads this ever has to take such steps, but maybe this experience of ours will help someone in the future."—L. G. Rilchey, Lincoln.

"(l)Is it legal to hunt doe deer, what is the possession limit, and is it legal to hunt deer after dark? (2) What game fish are in the Elkhorn River? (3) Is a license required for children under 16 to fish? (4) Is it legal to trap pheasants and quail?"—Michael D. Stout, Neligh.

(1) Doe deer will be a part of the firearm harvest in certain areas of the state this year. Bowhunters may take does anytime throughout their season. Firearm possession is one antlered deer with a fork on at least one antler, except in those areas where an antlerless deer will be allowed on the last day, or in the Omaha Unit where one deer either sex, may be taken throughout the season, October 28 through November 1. Shooting hours are from one-half hour before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset.

(2) Game fish found in the Elkhorn River, not necessarily common, are: channel and yellow catfish, white crappie, black crappie, largemouth bass, green sunfish, orange spotted sunfish, black bullhead, yellow bullhead, northern pike, goldeye, shovelnose sturgeon, bluegill, sauger, walleye, drum.

(3) Residents under 16 do not need a permit to fish.

(4) No.—Editor.

All Fur What?"I think OUTDOOR NEBRASKA is a wonderful outdoor magazine. However, there are some things I can't agree with, particularly the open season on mink, muskrats, and beaver. I have trapped and bought furs in southwest Nebraska for over 60 years, and while I cannot get out and catch them any more, I sure enjoyed it when I could. But I still buy fur every winter. To see the beaver and muskrats killed off in November and the first part of December when they are almost worthless doesn't seem right. Beaver and muskrats should not be caught before January 1 and the mink season should be closed not later than January 20.

"We'll wake up some of these days and find the best fur bearers in America, the beaver and mink, exterminated."—E. L. Campbell, Benkelman.

You can be assured that no season ever set by the state game commissions will be responsible for the extermination of any species. In Nebraska, except for highly localized areas, trappers do not harvest the yearly surplus of fur bearers, let alone cut into the breeding stock. One reason is this —we do not have the manpower. Our trapping license sales have droped more than half since 1954; trappers then numbered around 5,000, while last year's permits were about 2,200.

You are correct in stating that muskrat and beaver pelts are of poorer quality during the early part of Nebraska's current season (November 15 through March 15 for the species in question). But fur buyers pay more in November than they do later in the season, and the trapping business is a money proposition for most permit buyers.

Crop damage and flooding make the beaver a problem species. Biologists feel that the season could be removed entirely on this animal without harm.

Mink breeding season starts usually in latter January. But because a few animals may be taken in beaver sets, the trapping season was left to open with the others. It closes January 15. Our species are not in any danger.—Editor.

"We have lived in Nebraska only through two hunting seasons, but that has been sufficient to convince us that few states can match Nebraska for quality hunting, especially if a person is willing to keep a pointing dog.

"A hunter can have bag limits as well, if that is uppermost in his mind.

"There is too much criticism and too little appreciation of the proficiency of the Game Commission and the director, who have many interests to satisfy. Not many of us have to consider the concentrated gripes from some area, knowing as sure as the nose on your face that there will be surplus pheasants and quail after the season closes, only to be lost before the next breeding season.

"I would like to see more cheers and fewer jeers for a capable, dedicated, and relatively poorly paid people who are administering the wildlife resources of the state; and for the landowners, too, virtually every one of whom I have found to be considerate, even when I had an Omaha license on my car." —Walter H. Kittams, Omaha.

"This is a fine magazine, we not only subscribe to it but give it as a gift. Recently I purchased some land for hunting and fishing; however, it has one problem—a stream, a beautiful bass spot, but full of moss. Could you tell me how to get rid of the moss.

"Also, two small gravel pits are on the land, which seem to be full of carp. We do not object too much, the children enjoy catching them, but we cannot catch any other fish.

"Is it true the state would seine out these fish and stock the lakes with game fish? I am under the impression that we would have to let the public use the lakes then."—B. J. Minarik, Omaha.

The use of chemicals to control vegetation in a stream is extremely difficult. Doses have to be heavy in order to assure control; and there is danger they might be so heavy as to kill fish life. Any use of chemicals in a stream must be under the supervision of a Game Commission fisheries biologist unless the stream is entirely contained on your land.

In some cases the Game Commission will seine out carp from private lakes. However, it is doubtful that it would restock game fish since not all the carp can be removed by such a process as seining. The better method is rotenoning. You pay the cost of the rotenone, which is applied under the supervision of a fisheries biologist. If kill has been adequate, the Game Commission will furnish game fish for restocking. You are not required to open your waters to public fishing once this is done.—Editor.

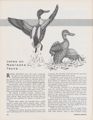

SHOVELLER

notes on Nebraska fauna...

RISING QUICKLY from the water, mounting straight up, and darting off with swift though somewhat erratic flight through the crisp fall air, the shoveller will present an exciting target to shotgunners this fall. In scientific circles this denizen of the swamp has been dubbed Spatula clypeata.

Occasionally called spoonbill, these ducks are easily recognized by the striking colors of the drake and the large bill of both sexes. Other characteristics of the drake include a dark green head, white chest, red breast and sides, and blue wing coverts.

The female is slightly smaller, mottled with brown and buff, with a pale buffy breast and blue wing coverts. Both sexes lack the fleshy lobes on the hind toes, marking the species as surface dabblers.

Unlike other ducks, the shoveller has a small throat, a weak voice, and is usually silent. Sometimes the hen indulges in a few feeble quacks, and the drake makes a low guttural woh, woh, woh, or took, took, took.

Common over North America, Europe, and Asia and wandering south to South America, Africa, and Australia, the shoveller is the best known and most widely distributed duck in the world.

Principally a bog-loving duck, the species is fond of sloughs, marshes, streams, and ponds where the birds dabble in shallows like obsessed mud larks. They are always associated with shallow pond holes and sluggish creeks as is characteristic of wet, grassy meadows in the Sand Hills.

The shoveller ventures to or through Nebraska from his wintering areas on the shallow inland waters along the Gulf of Mexico and south into the interior of Mexico. The duck nests in an area bordered on the south by Wisconsin, Iowa, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California.

In the spring the shoveller is not an early-starting migrant since he is not a hardy bird. The seasonal move usually gets under way before the end of March, but shovellers do not wholly disappear from the Gulf until early May. The first flights arrive in Nebraska by middle or late April.

While enroute shovellers travel in small flocks,

frequenting ponds and rivers, not associating much

with other species. Once to their summer range,

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

they spread out into sloughs, creeks, and marshes,

breaking up into pairs or small parties of three or

four.

they spread out into sloughs, creeks, and marshes,

breaking up into pairs or small parties of three or

four.

The male's courtship activities are undemonstrative. His ladylove is equally lacking in emotion. He swims slowly up to her, uttering a low guttural croak, and at the same time elevating his head and neck and jerking his bill upward. The female then bows in recognition, and both proceed to swim slowly around in cricles.

After courtship activities, the pair searches moist meadows, sloughs, and ponds for a suitable nest site. Often far from the nearest water in prairie regions, the nests are merely shallow depressions on the ground in an area well sheltered by a dense growth of native grasses.

The selected depression is filled with dry grasses and the new nest is then lined with breast feathers. The small eggs are then deposited in a pocket of the nest that is lined with soft down plucked from the hen's breast. As incubation progresses, more down is added. Raising only one brood per year, the hen lays from 6 to 14 but usually 10 to 12 eggs that are smaller and usually more elongated than those of pintails. The color varies from very pale olive buff to very pale greenish gray. The shell is thin and smooth with very little luster.

Incubation is entirely by the female, although the drake is nearby. After the first 14 to 17 days, the male abandons the hen.

Soon after hatching the young are led to the nearest water. Carefully guarded, they are taught to feed on insects and soft animal and vegetable foods. Immediately upon entering the water the downy ducklings display expert diving ability.

Olive brown to sepia-colored above, the young are mostly buffy brown and the crown of the head is a dark clove brown. Color of the back extends far down onto the sides of the chest and onto the flanks. The under parts are cream buff to ivory yellow deepening to a chamois color on the cheeks. There is a stripe of olive brown through the eye and a light buffy spot on each side of the back, behind the wings, and on each side of the rump.

The duckling's flank feathers appear before the mottled feathers of the breast and belly, together with the scapular and head plumage. Then the tail shafts and finally the all-important long primary and secondary feathers of the wings become visible.

The bill at hatching is no longer than the bill of any other duck at this age but it grows amazingly fast. At two weeks there is no difficulty in identifying the species.

The tongue, roof of the mouth, and the soft edges of the broad bill are all well supplied with nerves that are sensitive to touch and taste. These nerve endings help the bird distinguish particles of food from worthless material.

With special straining "teeth" and a highly sensitive mouth, the young shoveller seldom tips up to feed. He paddles along, skimming the surface, with head half submerged. Dabbling along in this manner, food and other material are taken into the mouth, tasted by the sensitive buds, and sifted out through the bill's pectinated bristles if unwanted.

Foods caught in this process include grasses, buds and young shoots of rushes, teal moss, various water lilies, duckweeds and pondweeds, small fishes and frogs, tadpoles, shrimps, leeches, and worms.

When the first frost of the season or the first cold snap comes rolling out of the north, the fall migration begins. Groups of late-migrating blue-winged teal are joined by shovellers that rejected their company just a few months earlier.

Hunters see the shovellers as a very sporting duck since he always seems alert and offers a challenge to the stalker. When alarmed he springs vertically from water or land with a strong upward bound and a loud rattling of his wings, to dart off with a swift, erratic flight, punctuated with sudden downward plunges that are hard to follow with a shotgun. The flight is much like that of the teals. Like them, the shoveller decoys readily and has the habit of circling to return to the decoys where he was shot at just a few minutes before. When found in good condition after a healthy summer these birds offer superb eating if the skin and underlying fatty material is removed prior to storage and cooking.

This strong, sturdy little flier is one of the state's important nesting ducks and one of the more numerous spring and fall migrants. Well adapted to surface feeding, easily satisfied as to nesting grounds, and a colorful duck, the shoveller is one of the most popular birds of Nebraska fauna.

THE END SEPTEMBER, 1961 27