OUTDOOR Nebraska

NOVEMBER 1960 25 cents COW COUNTRY BUCK Page 6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

NEBRASKA GAME COMMISSION: George Pinkerton, Beatrice, chairman; Robert H. Hall, Omaha, vice chairman; Keith Kreycik, Valentine; Wade Ellis, Alliance; LeRoy Bahensky, St. Paul; Don C. Smith, Franklin; A. I. Rauch, Holdrege PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION AND PARKS COMMISSION Editor: Dick H. Schaffer STAFF: J. Greg Smith, managing editor; Pete Czura, Mary Brashier, Gene Hornbeck, Claremont G. Pritchard DIRECTOR: M. O. Steen DIVISION CHIEFS: Eugene H. Baker, engineering and operations, administrative assistant; Willard R. Barbee, land management; Glen R. Foster, fisheries; Dick H. Schaffer, information and education; Jack D. Strain, state parks; Lloyd P. Vance, game NOVEMBER 1960 Vol. 38. No. 11 25 cents per copy $1.75 for one year $3 for two years Send subscriptions to: OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, State Capitol Lincoln 9 Second Class Postage Paid at Lincoln, Nebr. IN THIS ISSUE: IN THIS ISSUE: FACTS OF LIFE (Mel Steen) 3 COW COUNTRY BUCK (Gene Hornbeck) 6 SWEET TALK (Henry Reider) 8 WAIT AND SEE (J. Greg Smith) 10 GROW YOUR OWN (Neale Copple) 12 THE SQUIRREL AND I PRESSEY 16 NEBRASKA DOG CLUBS (Pete Czura)18 BILL AND JOE 20 PHEASANT HUNTER'S FORM CHART 21 QUAIL HUNTER'S FORM CHART 22 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 23 NOVEMBER HUNTING GUIDE 25 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA (Mary Brashier) 26 DEER FORM CHART 28A touch of the wilderness and the men who claimed it is reflected in this impressive picture by staff photographer Gene Hornbeck. Gene, ever on target when it comes to pictures, had his problems bagging a buck last season. All the he's were she's, and he saw a lot of Sand Hills country before he scored. Read of Gene's adventures in "Cow Country Buck" on page 6. Incidentally, if you plan on getting a deer this fall, check the back page for some slick hunting tips.

CHADRON, Fort Robinson, Lake Minatare, and Box Butte Reservoir, in that order, have the greatest need for future development by the Game Commission in northwestern Nebraska, is the opinion of Wade Ellis, Game Commissioner from Alliance.

"We need to improve roads at Chadron, and add more cabins. The new swimming pool, which will be ready next spring, will materially aid in providing recreation for residents in this area. Minatare and Box Butte need improvements in boating and water-skiing facilities."

Toad Stool Park in the Orella country is "one of the most unique formations in the United States," and needs development as a tourist attraction.

"But the duty of a Game Commissioner is more encompassing than just his district. He has a responsibility to all the citizens of the state. I am 100 per cent behind the chain-of-lakes proposal, and other Game Commission plans for the betterment of recreation and parks for all, from southeast to northwest."

Ellis, well-known attorney in Alliance, is a second-year Game Commissioner who has had a long term in public service. Box Butte county attorney for four years, he has also served on the Highway Advisory Commission.

Also engaged in farming and ranching, Ellis is a member of the Alliance Hereford Breeders Association and the Alliance Gun Club, both of which he helped organize. He is secretary of the Alliance Development Corporation, as well as an organizer of the group.

Ellis graduated from the University of Nebraska, obtained his law degree from Creighton University Law College, and attended graduate law school at George Washington University in Washington, D. C. He and his wife, Raye, have two children, Wade Jr., enrolled at Chadron State College, and Susan, a student at Alliance High School.

THE END CONSERVATION OFFICERS Albion—Wayne Craig, EX 5-2071 Alliance—Leon Cunningham, 1695 Alliance—Wayne S. Chord, 85-R4 Alma—William F. Bonsall, 154 Bassett—John Harpham, 334 Benkelman—H. Lee Bowers, 49R Bridgeport—Joe Ulrich, 100 Crawford—Cecil Avey, 228 Crete—Roy E. Owen, 446 Fremont—Andy Nielsen, PA 1-3030 Gering—Jim McCole, ID 6-2686 Grand Island—Fred Salak, DU 4-0582 Hastings—Bruce Wiebe, 2-8317 Humboldt—Raymond Frandsen, 5711 Humphrey—Lyman Wilkinson, 2663 Lexington—H. Burman Guyer, FA 4-3208 Lincoln—Norbert Kampsnider, IN 6-0971 Lincoln—Dale Bruha, GR 7-4258 McCook—Herman O. Schmidt, 992 Nebraska City—Max Showalter, 2148 W Litho U.S.A.—Nebraska Norfolk—Robert Downing, FR I -1435 North Loup—William J. Ahern HY 6-4232 North Plate—Samuel Grasmick LE 2-6226 North Platte—Karl Kuhlman, LE 2-0634 Odessa—Ed Greving, CE 4-6743 Ogallala—Loren Bunney, 28, 4-4107 Omaha—Robert Benson, 455-1382 O'Neill—Harry Spall, 637 Oshkosh—Donald D. Hunt, PR 2-3697 Plattsmouth—William Gurnett, 3201 Ponca—Richard Furley, 56 Rushville, William Anderson, DA 7-2166 Stromsburg—Gail Woodside, 5841 Tekamah—Richard Elston, 278R2 Thedford—Larry Iverson, Ml 56-451 Valentine—Jack Morgan, 504 Wahoo—Robert Ator, G! 3-3742 Wayne—Wilmer Young, II96W Litho U.S.A.- Nebraska Farmer Printing Co.

FACTS OF LIFE

We could double our pheasant harvest and still have plenty of birds to spare by Mel SteenNO FACT IN pheasant management is so well established as the one that we do not overshoot a pheasant population when we harvest only the cock.

This fact has been determined by long and painstaking research over many years and in many parts of the United States. From the game-manager's point of view, a "cocks only" regulation is as safe as a closed season. It has no measurable effect on the production of young the following spring.

To understand why this is true we must realize that the pheasant is a highly polygamous bird, and that enough cocks always escape the hunters to maintain fertility of the egg the following spring. The truth is we don't know how high a percentage of the cocks we can harvest before egg fertility begins to decline. We don't know because we have never reached that stage in any part of the nation.

In intensively hunted areas, the ratio at the end

of the hunting season has gone as low as one rooster

to 15 hens. This is a harvest of more than 90 per cent

of the cocks, yet even so no measurable decline in

NOVEMBER, 1960

3

the fertility of the egg has occurred. We do well to

take 30 per cent of our pheasant cocks in a Nebraska

season, and we usually average around 25 per cent

when we have a good crop of birds. It is evident

therefore, that we could double our harvest and have

plenty to spare.

the fertility of the egg has occurred. We do well to

take 30 per cent of our pheasant cocks in a Nebraska

season, and we usually average around 25 per cent

when we have a good crop of birds. It is evident

therefore, that we could double our harvest and have

plenty to spare.

Research has also demonstrated that the ability of the pheasant cock to take care of himself is the reason we cannot overharvest this bird. No matter how high hunting pressure has gone, enough roosters remained to carry on. They just wouldn't let themselves get killed by the hunters.

These facts have been determined by extensive and painstaking research.

Casual observation, on the other hand, will lead to the conclusion that they have been overharvested. When one finds a nest in the field full of unhatched eggs, the natural conclusion is that those eggs were infertile.

However, the scientist accepts this evidence only as proof that the eggs were not hatched. If they are not spoiled, the scientist takes them to the laboratory and examines them critically for fertility. Invariably he finds that the eggs have been fertilized.

There are a number of reasons why nests are abandoned. Sometimes the hen is killed by predators. Sometimes farm machinery does this, particularly mowers. Sometimes the hen is disturbed so much by cats, dogs, or other harassment that she moves to a safer location. Most often, however, the nest is one which we commonly refer to in game management as a "dump" nest.

We believe the pheasant hens build "dump" nests

because they have been bred to lay heavily. As a

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

consequence they lay eggs for some time before they

become "broody". Sometimes they drop eggs wherever the urge occurs, without even bothering to

build a nest.

consequence they lay eggs for some time before they

become "broody". Sometimes they drop eggs wherever the urge occurs, without even bothering to

build a nest.

The pheasants originally released in the Great Plains came from English game farms. The game farm operator desires hens that lay heavily, and eliminates those that do not. As far as he is concerned, this is only good business.

The game-farm operator who has hens that lay 75 eggs a year produces as many chicks with 1,000 hens as he can with 5,000 that lay only 15 eggs each season. This is true because the eggs are hatched in warm incubators, and the pheasant chicks reared in brooders.

Since all the strains of pheasants that were stocked in the Great Plains came from English game farms originally, they naturally had heavy egg-laying characteristics. These characteristics persist because they are genetic and well fixed. It must be remembered that the pheasant has been bred in captivity for centuries in England. It is not surprising, therefore, that our pheasant hens are inclined to build many a "dump" nest and lay more than they incubate.

The hunter is prone to judge pheasant populations and regulations by his hunting experience. However, easy hunting and consistently full bags are possible only if a minor part of the harvestable surplus is taken. The longer the season lasts, the wilder pheasants become, and the more difficult it is to take them.

As much as 65 per cent of the year's cock harvest in Nebraska is taken the first 10 days of the open season. From then on the cock harvest drops off rapidly. Only a small part of the year's harvest is taken during the latter part of the longer seasons.

The purpose of game management is to preserve and perpetuate wildlife resources in order that the people may use and enjoy them. This involves the responsibility to protect these resources, but also the duty to make them available to the extent that good management permits. Because pheasants get wild and hard to take is no reason why people should be denied a chance to hunt them. Why should we do this when we positively know that no harm can come from this hunting?

Environment is the key to the welfare and abundance of all life. This is just as true of the pheasant as it is any species. In areas where environment will support and protect 10 pheasants per square mile, we will have 10 pheasants per square mile. If the environment is good enough to support and protect 100 pheasants, there will be 100 pheasants. More than this will be produced, but this is all that will survive. In hunting we take only a part of this excess production. Contrary to popular opinion, hunting does not reduce the production and survival of next year's young—nature does that.

The best job we do in modern game management is to control hunter harvest to safe limits. In fact, we over-control most of the time. Unfortunately, however, we cannot regulate nature's harvest. We would like to, but the factors that determine environment and natural mortality are largely beyond our control.

Natural mortalities can only be reduced through better environment, and only the landowner can provide better environment. The predator, the parasite, the microbe, the hail storm, the flood, and the blizzard pay absolutely no attention to closed seasons and refuge signs.

But no matter how much pheasant environment may change, nor what the pheasant population may be, one fundamental fact can guide us—we cannot overshoot Nebraska pheasants in a "cocks only" season. The sooner we accept this truth, the more enjoyment and use we can make of our greatest game bird—the ring-necked pheasant.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 5

COW COUNTRY BUCK

by Gene Hornbeck Time was running out for me. Then came the moment I'd been hoping forWATCH them, Gene," Les warned. "They're getting jumpy and know we're here. Those 'mulies' will be coming out of that plum brush like turpentined cats."

All that I could see through the scope were the white rump patches of the deer as they fidgeted behind a screen of brush.

Les Kime, Valentine rancher and my guide in the vast Sand Hills area, hunkered beside me with his binoculars trained on the deer. Over 300 yards separated us. My 2X7 scope was set on full power, and the cross hairs were beginning to waver from the strain of holding the rifle on target. I was down in a sitting position, elbows resting on my knees, ready for the deer to show, hoping one would be a legal buck.

Dropping the muzzle of the .243 Winchester to relax my arms, I looked out across the valley and could barely distinguish the white rumps from the splotches of snow that lay on the hillside.

It was then that the deer spooked. Two does bounded to the top of the hill, as I quickly raised the scope. Another doe broke cover, heading parallel to the hilltop, followed by two more. A pair remained in the brush, and I swung to cover them. A big one broke, heading away from the others and I felt my pulse hammering in anticipation as he cleared the edge of the brush patch. Again the he was a she.

Another blank; the bucks were eluding us at

every turn. Maybe the entire population was of the

fairer sex. This was the second day of the hunt. I

had scoured the forests of Michigan many times for

the elusive whitetails, but this was my introduction to hunting deer in grouse cover. The weather

was perfect, unlike the cold blasts I'd been used

6

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

to. Though chilly in the morning, the day warmed

as the sun arced a clear-blue sky.

to. Though chilly in the morning, the day warmed

as the sun arced a clear-blue sky.

We were hunting the Snake River country near Les' ranch, 25 miles southwest of Valentine. This is the heart of the sprawling Nebraska cattle country. The grass and yucca-covered Sand Hills stretch for endless miles, broken occasionally by a stream course fed by seepage from a huge underground water supply.

The ranch straddles the Snake River just below beautiful Snake Falls. Ponderosa pine, cedar, and heavy brush hang precariously on the steep walls of the sometimes 300-foot-deep canyon.

I had sat along one of the fingers of the canyon the previous evening in hopes that a buck would come my way from the coolness of the gorge. A hunter's ears are of little value to him along the roaring Snake. The thunder of the falls and the constant howl of the wind whipping the ponderosas make hearing almost impossible. That evening a doe had come in along the canyon rim and was only 30 feet above me when I spotted her. It seemed as if she had suddenly sprouted from the ground.

When I didn't score the first day Les suggested that we try the hills. Perhaps the deer would be lying up in the patches of buck and plum brush.

It was near noon when we kicked up the seven does. After a long hike back to the car and a break for lunch, we decided to try the hills north of the river. This area was the southwestern portion of the Niobrara Division of the Nebraska National Forest, a misnomer, to say the least. Very little of the area is forested. The 110,000-acre tract is 90 per cent range land with only a token planting of cedar and jack pine.

Les and I began hiking a long range of hills, occasionally stalking to the top to glass the brush patches on the opposite hillsides. After an hour of hoofing, we called a halt atop a high hill overlooking a valley that stretched two miles to the east. I started to light up but Les reminded me that in a federal area smoking was prohibited.

"With things as dry as they are, anything could start a prairie fire," Les explained. "There's little fire protection out here, and with these winds this whole eastern pasture could burn out before we could get enough men in here to stop it."

Les glassed the sidehills leading away to the north. "I'm not certain," he (continued on page 24)

NOVEMBER, 1960 7

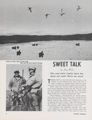

SWEET TALK

by Henry Reider This reed artist creates music few ducks can resist. Heres my secretTHERE ISN'T a duck that doesn't hearken to the "quack" of the mallard hen. She's the first to warn of guns in a marsh below, and she gives the word, too, when she finds a lagoon full of goodies.

That's why the raucous duck conservation you hear across Nebraska waters this fall will be tossed out by the female of the mallard species. That's why, too, the squawks arising from the most successful duck blinds are imitation mallard-hen talk.

Duck calling's a fast-growing art among sportsmen, and a lot of the men I know do it simply for the fun of having a few "Susies" bobbing around in their blocks. But on the serious side, calling is a means of getting the birds within range and killing with the first shot. Like a good dog, it's a way of eliminating cripples, while adding pleasure to the hunt.

All puddlers—the mallards, pintails, teal, gadwalls, baldpates, shovellers—have pretty much the

same habits. They like the same kind of food, the

8

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

same basins or lakes for stopovers. Most likely, a

wary mallard hen is their leader, even if it's a

showier greenhead out in front. She's the one who

gives the final O.K. to a resting marsh or must be

fooled by a set of decoys. Other ducks take their cue

from her and follow in. And since she's social and

talkative by nature, a bit of smooth seductive calling

helps.

same basins or lakes for stopovers. Most likely, a

wary mallard hen is their leader, even if it's a

showier greenhead out in front. She's the one who

gives the final O.K. to a resting marsh or must be

fooled by a set of decoys. Other ducks take their cue

from her and follow in. And since she's social and

talkative by nature, a bit of smooth seductive calling

helps.

Calling serves two purposes, as far as the ducks are concerned. It advertises the whereabouts of a choice marsh and assures the fliers that everything is cozy and safe and there's plenty of juicy plants down below. So the hunter keeps his calls soothing and inviting, never harsh.

Three basic calls will suffice. The "hail and come back", more commonly known as the "high-ball", is the first announcement to a flock above that a just-right marsh is waiting. This call is as loud and as high as the hunter can make it. It begins with one or two dragged-out notes, then runs down the scale with a series of shorter quacks. As the birds approach the tempo is speeded up. Repeat once or twice, varying the number of notes.

Weather conditions can alter plans. If the birds are riding a stiff wind in from the north, the hail and come back pitched out after they go over will hit them just when the marsh registers in their duck minds. Bluebird weather, too, forces the hunter to work a little more. In rough weather little calling is needed, for the birds are anxious to come in.

After the first call to the flock, watch the birds closely. If one breaks, or casts an eye down at you, repeat the call. If they keep going, don't give up. They may continue for three miles or so, then it finally works on them and they swing back. Or they may have already decided, and are taking advantage of the wind, since they prefer to come in against it.

When they come back for a second pass, switch to the "morning and mating call" or the "feed, chuckle, and cluck", depending on how much on top of you they are. At a distance yet, try the morning welcome of the hen. It's a three-note affair, the first higher and a mite longer. After repeating this, give the answer, six quacks, the fourth a little higher pitched.

About now you ought to hardly be able to stand it. Keep down. The ducks know what a marsh should look like, and if they see the bright and shining full moon of your face sticking up out of the reeds, they'll fly skyward faster than any shot you could get off.

And, too, this is about the time an overanxious caller rips off an agonizing "qua-aack" on his horn and spooks the entire show. If you're subject to nerves, quit right now and take your chances. It's better to do less than more and ruin it. If you can contain yourself, start the feed> chuckle, and cluck as they set their wings and even as some start rocking gently to lose altitude.

Mouth "take-it-take-it" or "kitty-kitty-kitty" into the call with machine-gun speed, occasionally inserting a "quack". Fairly burst with invitation as the ducks drop nearer. Now's the time to blast away. .

Wandering singles and pairs are looking for company, usually voicing their feelings in loud and lusty quacks. Answer their demand with similar notes, they'll fly over to see if you're the flock they've lost.

During closed season, take a perch on a comfortable stump near a flock of domesticated mallards, and strike up a conversation. There's no better way to learn duck language.

With no barnyard flock handy, you can invest in a phonograph record or two. Practice at full blast right next to it and hope for understanding neighbors.

There are roughly over a million artificial calls on the market today, well over half of these duck and goose calls. Most are wood, but the plastic ones are catching on fast. Old-timers aren't won over, but claims are that the plastics are more durable, don't absorb moisture from the caller's breath, and better maintain their tone. They probably are quite satisfactory for the average hunter.

Carry three or four in your pocket. Especially on cold mornings, your breath condensates on the reed, resulting in an off tone. You can take the call apart and wipe off the reed, but don't bend it in the process. Incidentally, you'll accumulate seeds and plant parts in your pockets crawling up to the blind. Blow through the call from the wrong end to blast these out before the action begins.

Duck hunting is a lot more fun when you can talk the birds right into your blocks. Tuck a call into your pocket next time you go out. Even the experts don't stop all flocks. But then, you know what they say about beginner's luck.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 9

WAIT AND SEE

by J. Greg Smith A more varied bag coming up, if new species take holdTHROUGHOUT the rolling, fall-bedecked grandeur of NEBRASKAland, King Ringneck reigns supreme, the target for an army of hunters campaigning in the vast reaches of the "Pheasant Capitol of the World". Millions of gaudy roosters secreting every nook-and-cranny covert back up this proud claim, and both sportsmen and nonsportsmen alike have discovered that the Asian immigrant, introduced to then bird-hungry Nebraska 45 years ago, not only provides prime sport but an added ring in the cash register as well.

Establishment of the pheasant in the state is a real success story. Probably not more than 500 pairs made up the parent stock of the millions that live here today. The Game Commission, ever on the lookout for additional species to add even more hunting and fishing opportunities, had scored in a big way.

Success stories can be duplicated. In the very near future, other species, many with the same potentials as those reaped following the pheasant plant, may soon to be added to the state's formidable list of game and fish targets.

Merriam's turkey, scaled quail, and coturnix may

be included with the upland-game-bird bonanza of

pheasant, bobwhite, prairie chicken, and sharp-tailed

grouse. The pronghorn antelope population, restricted to a 3,500 count in the panhandle, could

10

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

blossom many thousands in the Sand Hills. Warmwater trout, kokanee salmon, redear sunfish, and

muskellunge, the greatest fighter of them all, may

soon join other new additions like the northern,

walleye, and smallmouthed bass.

blossom many thousands in the Sand Hills. Warmwater trout, kokanee salmon, redear sunfish, and

muskellunge, the greatest fighter of them all, may

soon join other new additions like the northern,

walleye, and smallmouthed bass.

Introducing new species is not a chance affair. Many factors are considered before an actual plant is made. Habitat, carrying capacity, effect on environment and other animals, and game qualities are among the many points that receive careful study. If the species passes these tests, experimental planting follows. Final success of the introduction, of course, is determined when legal hunting or fishing seasons are declared.

What about the game and fish introductions mentioned here? Have they passed the tests that will assure future hunting and fishing opportunities? And if they have, how long will it be before state sportsmen get a crack at them? For some, the answers are most encouraging; for others, we can only wait and see.

Little more needs to be known about the Merriam's except perhaps the weapon to be used when the season opens in the next two or three years. At least, that's the present outlook. Unlike the eastern variety, the Merriam's have taken to Nebraska in a big way. The birds were transplanted here from wild flocks in Wyoming and South Dakota during the winter of 1958-59. Some 28 turkeys were planted in the Cottonwood Creek area near Crawford and the Dead Horse Creek area near Chadron. This year's population will not be known until flock counts are taken this winter, but it's estimated that there are between 300 and 350 turkeys in the two areas. Birds will be transplanted from the two flocks if numbers continue to increase. The average brood size has seven poults to each hen.

It's too early to tell how the scaled quail will do in the state. Over 600 have been released in 11 suitable sites in the Sand Hills. The unique area is similar to the bird's habitat in the Southwest. It's because of this and the apparent success of private plants by Alfred Meeks on the Calamus River in Loup County that the Commission went into the scaled quail experimental program. If successful, this quail, a real sporting bird with top table qualities, will augment the area's already prime upland gunning.

Whether the coturnix will take hold is anyone's guess at this time. Reports of kills are still coming in. State hunters have reported taking hundreds of coturnix, but most of these kills have not been confirmed. Other states are also reporting coturnix bags. One Alabaman hunting out of Montgomery last fall said he hit a jack pot of birds. He and his hunting partner bagged 12 of the speedy migrants. The hunter noticed that these quail flushed separately and discovered, once the shoot was over, that he had taken Nebraska-banded coturnix.

Introduction of the coturnix represents one of the most organized efforts to (continued on page 25)

GROW YOUR OWN

by Neale Copple Takes patience on your part, Pop, but it pays off in yearsTHERE ARE a good many ways to get yourself a fishing partner, but one of the most satisfying is to grow your own.

The key to the whole project is patience—patience from the time you first see the red, wrinkled little guy until you finally get him to dunk his first worm.

Fatherly pride will help you over the first big hump. It happens about the time your wife comes out of the anesthetic and mumbles something about "You've got yourself a fishing partner."

If you weren't under a strain, you'd admit immediately that this was nothing more than a very young baby. As for making a fisherman out of him, the chances seem pretty slim. It actually takes from three to four weeks to really spot the signs.

1. Fishermen are supposed to like their sleep. (This boy can take 20 hours of shut-eye a day without even being embarrassed about it.)

2. Fishermen are not supposed to mind eating at odd hours. (When this boy is awake, he is yelling for food. And he seems to like it best at 3 a.m. This second point leads logically to the third.)

3. Fishermen don't mind arising at early hours. (This boy not only does not mind arising at early hours, he makes it a point to always be awake between 3 and 5 a.m.)

4. Fishermen aren't bothered by a little dampness. (At just about any given moment this boy is somewhere between damp and wringing wet.)

From this point on, your cultivation of a fishing partner requires a combination of subtlety along with patience.

At about two years, you'll find the boy takes an interest in books—little books, hundreds of them all over the house. He soon learns to pick out the pictures of the cows, horses, dogs, and cats. So what's wrong with slipping a couple of outdoor magazines into the stack to add to his worldly knowledge?

And then, of course, there are the toys. By the

time the prospective fishing buddy is three years

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

old, you'll find difficulty walking across the floor of

any room in the house without crushing a treasured

toy. Now with all this clutter of toys about, there

can't be anything very unethical about slipping a

toy rod and reel into the pile.

old, you'll find difficulty walking across the floor of

any room in the house without crushing a treasured

toy. Now with all this clutter of toys about, there

can't be anything very unethical about slipping a

toy rod and reel into the pile.

But don't let it bother you if your son has some difficulty in understanding the difference between hunting and fishing. He's likely to call his reel and rod his "hunting equipment". Patience is your only hope at this point.

By the time the boy is able to hold up three fingers when his aunties ask him how old he is, he will also be playing little games. There are all kinds of educational toys. So, what's so uneducational about a little game that involves a magnet on the end of a fishing rod and some metal fish?

Once again, you may encounter difficulty over the "hunting" and "fishing" bit. Don't let it bother you when he takes out his rod and goes "hunting" for the tiny metal fish. The boy'll get the word. Just give him time.

But not too much time. When he has reached four summers, he's ready for the real thing. So you make the selection of his first real gear with a good deal of care. You know it's foolish to put too much money into it and to make it too complicated.

You end up, perhaps, with a small glass rod, a plastic reel, and maybe a little red tackle box. The reception of the new equipment may puzzle you. He'll be delighted, but he may be in doubt as to what it's all about.

"What is it?" he may ask.

"Fishing equipment," he is told. "A rod, a reel, and a little red tackle box."

"Oh, boy," he chortles as he gathers it all into his chubby arms.

And on his way into the kitchen, you hear him tell his mother, "Look, I've got hunting equipment—a rod, a reel, and a little red suitcase."

Patience, man. Patience.

He is still calling it his little red suitcase as he lugs it out of the car on his first fishing trip—a trip to a little lagoon where the bullheads are all but pushing one another up on the beach.

He may protest as you bait up his hook with a big fat worm. But you can overcome those objections when you explain it's not the pet worm he has been keeping at home.

Now comes the moment. You flip out that worm where you know a dozen hungry bullheads are waiting.

"Now you take the rod," you tell him, "and wait for the bite."

He'll wait all right—maybe five seconds before he drags the poor worm's remains back to shore.

"So where's the fish?"

You explain patiently—the first of 20 times—that he's going to have to wait a little bit for the fish. Then comes the worm-wearing-out procedure. For almost an eternity, unhappy worms are dragged out of the water and along the beach. But finally one stays in just long enough for an unusually speedy bullhead to grab it.

He heaves. You heave. And somehow that startled bullhead is dragged ashore.

With the fish waving in front of his nose in the dull light of late evening, he says, "Looks like a fish."

"It is a fish," you shout with exultation, "your very first fish."

He babbles about his first fish and hunting as you load him and his equipment into the car. And as you drive off, he is still mumbling.

"What is it, son?"

"Have you got my fish in the car?"

"Yes," you assure him.

"And my hunting equipment?"

"Sure, son," you repty with resignation.

"And my little red suitcase?"

"Yes, son," you reply, realizing it really doesn't make much difference what he calls his gear anyhow.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 13

THE SQUIRRELS AND I

A Photo Story by Gene Hornbeck

PRESSEY

Mixed fare of gunning aching for public useARE YOU LOOKING for your hunter's paradise? You know, it's that place you've always dreamed about but maybe never really hoped to find, the place where you alone could take your pick of targets without ever being worried about too much competition. You don't have to look—or dream—any more. Pressey Special Use Area, tucked in the middle of the fabulous Sand Hills on the South Loup River south of Broken Bow, is that paradise, or, at least, the next thing to it.

Here's a 1,600-acre spot that almost matches the state's prime Sacramento hunting area when it comes to pheasants. And it, like Sacramento, is open to all. Gaudy roosters are everywhere: in the thick foliage along the river, the lush cornfields nearby, and the habitat plantings in the fields.

But pheasants, prized as they are, aren't the only targets. Coveys of quail can be found along the Loup and sharptails in the rolling grasslands. And if you get your fill of these you can blast away at squirrels, cottontails, and jacks. Nor is this all. Prime trophy mule deer like the Pressey spread, and are ready to offer any hunter a go for his money.

There's more than hunting, however. The river

is a focal point of an impressive scenic vista. Giant

cottonwoods, pines, cedars, and ash crowd around

the Loup, all ablaze now with the rich colors of fall.

These woods are the perfect setting for a well-cared-for picnic and camping area. Picnic tables, fireplaces

with wood, well water, playground equipment including swings, teeter-totter, monkey bars and such

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

are spotted strategically throughout. Ancient orchards nearby offer apples, peaches, and pears to

those who will take the time to get them.

are spotted strategically throughout. Ancient orchards nearby offer apples, peaches, and pears to

those who will take the time to get them.

Pressey wasn't always such a paradise. Sure, it had all the raw resources to make such a creation—the Loup, the wooded bottom lands, cornfields, and hills—but these provided little in the way of recreation when the Game Commission was given the area in 1943. Outdoorsmen were fortunate, however, that the former owner, the late Henry E. Pressey, had the vision to see what could be done with land. An ardent outdoorsman, he knew that his property could blossom into what it is today under Game Commission stewardship.

Co-operating with the Soil Conservation Service, the Commission launched a vast improvement program soon after the area was acquired. Cattle were removed from the range to allow it to recover. Native perennial grasses were planted and gullies fenced to check erosion. Sweet clover was planted along the river for pheasant use. Russian olive, multiflora rose, American plum, sand cherry, and honeysuckle were planted to make homes for wildlife. Red cedar and ponderosa were planted in key spots as part of the improvement program.

One look at Pressey today, and you can see what these accomplishments have done for the area. Habitat plantings provide cover for bountiful upland-game bird and small-game populations. The 1,100 acres of range land support a lessee's sleek Herefords on a sound grazing plan. Tree and grass plantings in the recreation area make it a welcome oasis in the vast prairie country. The farm site, now managed by a tenant, produces a bumper crop of corn.

Pressey is a working demonstration of how the application of sound land-management techniques pays off in a rich harvest in wildlife as well as crops and cattle. Landowners desiring to match this kind of productivity should visit the area to see what can be accomplished. It shows, more than any words can relate, the importance of good management.

There is another lesson to be learned at Pressey. Before improvements were made, the overworked, overgrazed area was almost barren of wildlife. Now game is abundant throughout, pointing up the fact that environment is the key to game abundance.

Unfortunately, this prime hunting area is utilized by too fe,w hunters. Only two or three hunting parties worked Pressey the first day of the season last year. After that, only an occasional hunter took on its bonanza of birds. There was a bonanza just as there is today. The tenant reported seeing 147 pheasants along a 1%-mile strip.

Access to this Sand Hills playground is no problem. In fact, paved State Highway No. 21 splits the area in two. Pressey is only a short five miles north of Oconto and only 15 miles from Broken Bow.

There's still plenty of time to hunt Pressey. Once there, you'll see why some consider it their hunting paradise. It is a paradise, open to you year around, its features and its targets the result of sound management of the land.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 17

NEBRASKA DOG CLUBS

by Pete CzuraDID YOU ever see 50 sporting-dog lovers working diligently to improve just one dog's ability at the retrieving or pointing game? It's being done. On any given week end you'll find members of dog clubs scattered throughout the state lending the kind of know-how that makes for top hunting dogs.

One of the largest and most active organizations in Nebraska is the. Missouri Valley Hunt Club of Omaha. It's the oldest retriever club west of the Mississippi, and was organized to conserve game by the use of retrievers afield. Boasting a membership of about 75, the organization sponsors local trials to give dogs experience in retrieving under hunting conditions. Each year two big get-togethers sanctioned by the American Kennel Club are held. Monthly trials are held the second Sunday of each month.

Banded in one common cause, men and dogs prove that it takes teamwork to make a hunterMembers like Bing Grunwald, D. L. Walters, Bob Howard, Jim Columbo, Stanley Lacy, Jerry Ault, Robert Mullen, Courtney Quinn, and Nancy Walters have brought prestige to the organization.

D. L. Walters, for instance, has trained and handled 13 field-trial champions and this year has 7 retrievers qualified for the National Retriever Trial Championship in St. Louis. Bob Howard made 7 out of 8 retrievers field-trial champions. Bing Grunwald owns and competes with 2 national champions: Nodak Cindy, 1957 National Retriever Derby Champion, and Tar Baby, the 1958 National Amateur Champion. For these and other accomplishments, Grunwald received the coveted Martin Hogan award in recogninition of his unfailing activities in retriever trials and great contributions to the furtherance of superb retriever work with his great Labradors. Only 8 other people in this country have received this distinguished honor.

Another active group is the Central Retriever Club made up of members from Hastings and Grand Island. This group holds practice trials the first Sunday of each month. These are open to all, and give owners a chance to test their dogs under field-trial conditions. Ribbons are awarded to placing dogs, but these affairs are much more informal than a licensed trial.

Dogs are primarily trained for hunting, since most dogs are extensively used afield and in duck blinds. Actually, club trials take second place to the pleasure of hunting with a capable sporting dog, but trials are an excellent method of keeping a dog sharp all year. Also, trial competition makes better gun dogs and improves handling techniques.

Harold Johnson of Elm Creek is a classic example

of what a hard-working club member can do. His

great Chesapeake Bay retriever, Star King of Mt.

Joy, is both an Amateur Field Champion and Field

Trial Champion. This dog hunts every day during

the hunting season, and has probably brought as

many waterfowl to hand as any living retriever.

Clayton Beadle of Grand Island is another enthusiast

who has developed a great retriever in Now Then of

Deerwood. Others who are very active in the Central

Nebraska Retriever Club are Lloyd Kissel and Henry

Schuff of Grand Island and O. H. Peyton, Robert

Ray, and Don Glass of Hastings. Robert, treasurer

18

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of the club, won the National Chesapeake Trial

Derby with his outstanding meat hound, Jimbo.

Last year, Don placed his fine Chesapeake bitch

third in the National Chesapeake Trial Derby.

of the club, won the National Chesapeake Trial

Derby with his outstanding meat hound, Jimbo.

Last year, Don placed his fine Chesapeake bitch

third in the National Chesapeake Trial Derby.

The Platte Valley and Setter Association of Grand Island is one of the oldest pointing clubs in the state. According to President Jim Kellog, the club holds two major field trials a year in order to bring a better class of pointer to the front, and to create a more enjoyable mode of hunting with competent dogs.

Member Roy Jines is one of the country's outstanding professional trainers and handlers of pointing breeds. His recent major wins include the United States Chicken Championship and the Invitational Match where only the nation's top 24 dogs competed.

Another group of dog enthusiasts, The German Shorthaired Pointer Club of Nebraska, headquarters in Omaha. The club was founded in 1952 to further the short-hairs as a sporting breed. Two AKC-licensed point trials are held each year, and championship points are awarded to placing dogs. The organization is also very active in local and national bench shows.

For real down-to-earth dog-handling principles, you'll have to give the blue ribbon to Nebraska Dog and Hunt Club of Lincoln. It rates as one of the finest in the state. Retriever enthusiasts are invited to attend and visit with club members when they hold their practice trials on their fine club grounds in Lincoln.

The Great Plains Beagle Club is one of the newest and fastest growing clubs in the state. It was originated in January by six beagle supporters. In less than 10 months, the club has grown to about 50 members.

The primary purpose of the G. P. B. C. is the improvement of beagles through field trials and conformation matches. Secondary purposes involve fellowship and friendly competition among persons interested in the breed.

Under the leadership of President C. O. Neidt of Lincoln, the club is making an impressive name among beaglers. Several dogs have scored well in regional and local events. Among the conformation winners are: Champion Whitson's Tine Tim, 13-inch male owned by Niel Whitrow, Lincoln; Champion Travis Court Quality Quail, 15-inch female owned by Neidt; and Dach's Den Bonnie, 15-inch female owned by Peggy Beard, Lincoln.

Last, but certainly not least, is the Prairie States Vizsla Club. It has many active members in Nebraska boosting the foreign breed including Mr. and Mrs. Meurice D. Graff of Seward, Barbara Langfeld of Papillion (her dogs are direct descendants of the first Vizsla imports brought to our country), Walter "Doc" Beyers of Lincoln, and Joe Dolezal of David City. Each fall this group sponsors a sanctioned trial with Weimaraners, German short-hairs, pointing Griffons, Drathhaars, and Vizslas competing for top honors.

Prominent Irish setter supporters are: Dr. Earl Brown of Lincoln, Floyd Crosley of Fremont with his nationally famous Shamrock line; Mr. and Mrs. Erich H. Hartmann of Lincoln, professional handlers; Larry Gaddis, son of Col. and Mrs. Gaddis of Lincoln; Red Hoffman, Mr. and Mrs. Carl Rasmussen and Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Updike, all of Fremont. All have done yeoman work in restoring the Irish clan to its former pinnacles of glory. And Jeanette Murphy of Omaha has one of the hottest show prospects, winning all kinds of honors.

Of course, there are other active sporting-dog clubs in the state. They include Husker Bird Dog Club, Randy Horsley, Lincoln, president, and the Grand Island Brittany Club, John Seery, president.

If you wish to lend your support to your favorite breed, why not join one of these clubs? What's best about each outfit is the intense rivalry and congenial friendship found among all members. For one thing, each club firmly believes they have the best sporting dog going. That's good. Competition creates higher standards, and this in turn leads to a continual improvement in all sporting-dog breeds. Don't shy away from joining because you don't own a dog. That's easy to fix. There's always an outstanding litter or two available. Just ask any of the clubs for help. You'll be swamped with offers.

THE END

BILL and JOE

Add 1 minute, subtract 13 miles. Total: sunrise chaosON MOST ANY duck-season sunrise, you'll be apt to find at least two furrow-browed waterfowlers like Bill and Joe hunched in their blind trying to figure out a tiny slip of paper which is supposed to give them the legal shooting hours in their area. The Game Commission publishes these state-wide sunrise-sunset schedules during the season for the convenience of the hunters, but only for seven key points. The schedules couldn't begin to take in all the areas in between, and that's where the problem comes in. For each 13 miles west of a point, the hunter must add a minute for sunrise time; for each 13 east, he must subtract a minute. Unfortunately, Bill and Joe, the creations of Conservation Officer Loron Bunney's imaginative pen, aren't too sharp when it comes to figures. You can imagine what happens:

Hurry, Bill, grab that sack of decoys and I'll carry the guns. Believe me, I don't want to be late.

Right. I would rather have that first 30 minutes before sunrise than any other two hours of the day. Well, we are to the blind. Where do you want the decoys, Joe?

Just east of the blind about 30 yards. But hurry. What time have you got, Bill?

5:15.

Bill, did you check the paper to see what time it's legal to shoot?

No but I have the Commission's sunrise table in my billfold. Let me check and I'll tell you. Well, it's a little more complicated than I thought. It only lists Valentine, Scottsbluff, and North Platte. Now I got it. It rises at North Platte at 6:48. Joe,we have plenty of time. It's only 5:25.

But Bill, does the sun rise at North Platte at the same time it does here?

Let me check that table again. It says here to calculate the time east of North Platte to subtract one minute for each 13 miles, and if you are west of North Platte, add one minute for each 13 miles. Don't look now, Joe, but a bunch of ducks just landed in our decoys.

Take it easy, Bill, we'll raise up and pop them when the legal time comes. What time is it now?

It's 5:30. Listen to that bombardment. Some poor sports are always jumping the gun. When is the legal time, Bill?

Just keep your shirt on. I'll have it in a minute. How far are we west of North Platte?

How would I know, probably 65 miles. Why?

Well, you see we have to subtract one mile for every 13 minutes, or did it say to add? Let me see that table again. How many times will 13 go into 65, Joe?

Search me. I never was good at arithmetic. Hurry, Bill. It's broad daylight.

Plenty of time, Joe. Sunrise at North Platte is 6:48.

Yes, but I thought we could start shooting 30 minutes before sunrise.

Right you are, but I haven't got these 13's and these one minutes figured out yet. How do I know when the sun rises here at Lake McConaughy? Now lets see, for every 65 minutes I subtract 13 miles.

Hurry, Bill, it must be nearly time to shoot.

Oh SHUT UP, Joe, this thing is driving me nuts.

Now see what you've done, Bill. You raised your voice so loud I saw 50 ducks leave our decoys.

What time is it, Joe?

5:40.

Let's see, add one minute. Check, Joe, and see if it says to add or subtract.

Oh, Oh, Bill, we have company. It's two of those gun-jumpers coming out of the river with four mallards, all killed too early.

Well, of all things. If it isn't Charlie and Bud. Hi, Charlie, hi, Bud. Since when did you guys start violating by killing a limit of ducks before the legal starting time?

What do you mean, shooting early? The legal time to start shooting this morning according to the shooting-hour guide in the Keith County News was 5:23, and we got our first bunch in at 5:25 and filled our bag before sunrise. How come you guys weren't shooting?

Well, I'll tell you boys, Bill, the dumb ox . . . well just skip it boys. Not to change the subject, but isn't that a beautiful sunrise, with the great Lake McConaughy in the foreground?

THE END 20 NOVEMBER, 1960

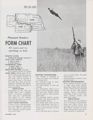

Pheasant Hunter's FORM CHART

Hit toosts and try psychology on birds SEASON DATES: October 22 through January 8 DAILY BAG LIMITS: 3 (three) Zone 1 5 (five) Zone 2 POSSESSION LIMIT: 9 (nine) Zone 1 15 (fifteen) Zone 2 SHOOTING HOURS: One-half hour before sunrise to sunset OPEN AREA: Entire state. In order to reduce gunning pressure from the eastern portion of the state, and to harvest a larger game crop in the west, the state has been zoned for pheasant hunting. See regulations for exact description of zone boundaries. POPULATION Comparable to last year. Although there was a slightly lower breeding population than last year, reproduction was higher in the western zone and population is as good or better than last year. LAST YEAR'S HARVEST A take of only 1,220,000 pheasants was bagged by sportsmen last year. But it could have been 2,000,000 without bothering brood stock HUNTING SUGGESTIONS The "dirtier" a cornfield, or cover, the better your chances of taking birds Hit roosting areas in early morning and at dusk Use bad weather to your advantage Try psychology. Take 4 to 5 steps in likely pheasant hiding spot and stop. Fidgety birds, figuring they've been spotted, often flush Try drainage ditches, brooks, potholes, and farm ponds for spine-tingling action Use proper gun loads. If you enjoy hamburgers then No. 2 and 4 will do the job. But to obtain a good carcass, try Nos. and 71/2 Use a sporting dog to retrieve all you knock down. It's good conservation. ...Ask permission to hunt on any private lands HUNTER REQUIREMENTS ...Every person 16 years of age or older must have upland-game-bird stamp and hunting permit. These can be obtained at any of the 1,200 permit vendors. Every nonresident, regardless of age or sex, must have hunting permit and game-bird stamp PREDICTIONS ...Best spots to hit are southern tier of counties; along Republican and Platte rivers and drainage systems; Dawes and Box Butte counties in Pine Ridge and Kimball and Cheyenne counties in panhandle NOVEMBER, 1960 21

Quail Hunter's FORM CHART

Less than last year but lots still here SEASON DATES: October 22 through December 11 (Southern area) October 22 through November 20 (Northern area) DAILY BAG LIMIT: 6 (six) Southern area 4 (four) Northern area POSSESSION LIMIT: 18 (eighteen) Southern area 12 (twelve) Northern area SHOOTING HOURS: One-half hour before sunrise to sunset OPEN AREAS: See regulations for boundary descriptions of open areas POPULATIONS Although quail population is approximately 50 per cent down from last year's bumper crop, it is still 15 per cent above the 15-year average LAST YEAR'S HARVEST Almost half-million birds were taken. However, this could have been doubled without injuring quail population HUNTING SUGGESTIONS Use sporting dogs to find and retrieve downed birds Ask for permission to hunt on private lands Hit fields and open areas before noon. At. midday search the fairly heavy cover Heavy cover, especially woody cover, is good to hit when weather gets nippy If birds are spooky, look for them, in heavy grass or weed cover, vine tangles, hedgerows, and brier patches Modified and improved-cylinder gun bores are the best, and top ammunition loads to use are Nos. 8 and 9 HUNTER REQUIREMENTS ...Every person 16 years of age or older must have upland-game-bird stamp and hunting permit. These can be obtained at any one of the 1,200 permit .vendors. Every nonresident, regardless of age or sex, must have hunting permit and game-bird stamp PREDICTIONS ...Nebraska's heaviest quail concentrations are found in the southeast, and, of course, that's where you'll get top action. But the Republican River Drainage in the southwest and south-central sections of the state are good as are the Loup and Platte River drainages 22 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE

Frozen With FrightPENNSYLVANIA . . . While on driving patrol recently, Game Protector Leo Badger came upon three rabbits sitting nose-to-nose in the middle of a dirt road. He had to make a complete stop to avoid hitting them. He quickly learned the reason: A Cooper's hawk had made a pass at them, and they were frozen with fear. Badger almost had to kick them off the road.

Is This Justice?ONTARIO ... An ardent angler appeared in court for fishing without a license. The magistrate was an enthusiastic fisherman. After seeing the evidence, a seven-pound trout, he intoned, "Ten dollars for catching a fish while not having a license to do so, and $25 for refusing to tell the court where you caught it."

PENNSYLVANIA . . . The old saying gunpowder and alcohol don't mix might well be changed to poachers and beer don't mix in a northern Pennsylvania county. A certain poacher will either keep his voice low or abstain from the old "tongue loosener" should he again take game out of season.

This thirsty violator was overheard attempting to trade venison for beer. When the local game protector heard of the incident, he searched the man's residence, found parts of deer, and successfully prosecuted the culprit. The poacher's thirst cost him $100 and costs as well as loss of hunting privileges for three years.

People Give Frog AidMISSOURI . . . Conservation Agent Clyde Wilson didn't realize how much of a helping hand some people want to give wildlife until told of this incident:

A farmer noted lights around a car near his fence one night and went to investigate. The car fled. He chased it, got the license number, and relayed the information to a state trooper. The patrolman traced the car and questioned the occupants. They said they had seen a large frog crossing the road and that's why they were out with flashlights. Yes, they knew the season on frogs wasn't open yet. They were just helping him "get across the road safely."

Anglers Big LosersWEST VIRGINIA . . . Anglers were the big losers as the result of an industrial accident on the Kanawha River. One of the heaviest fish kills ever was recorded when a barge delivering products to an industrial plant leaked methyl alcohol into the stream. Observers estimated the kill at a million in the oxygen-depleted water. Stream banks were also crowded by crayfish leaving the water.

COW COUNTRY BUCK

(continued from page 7)said, "but I think there's a muley in that patch of brush about a half mile up along the sidehill. Here, take a look."

The slope tapered away toward the north with a point swinging eastward into the valley like a giant foot. Back toward the heel of the point, I picked up a small patch of plum brush in the glasses and began studying it inch by inch. A small, heart-shaped patch of white drew my attention.

The minutes ticked off as we waited for the deer to show. Finally I had all I could take. Easing off the hill, I pussyfooted toward the brush and the deer.

It was a big doe, flattened out along the ground. Even her ears were dropped as she tried to conceal herself. I unlimbered the telephoto-rigged 35mm and began walking in, snapping a picture on every step. Finally she bolted, tearing out of the brush in typical bouncing mule-deer fashion.

The day passed with still no sight of antlers. Four does showed singly over the afternoon, all within easy rifle range, but the males of the species were nowhere to be found.

The third day dawned bright and clear. Mrs. Kime was up before dawn preparing a spread of eggs, hash browns, steak, toast, and scalding-hot coffee. All disappeared in quick order as Les and I stoked up for the day's hunt.

"I have to be back in Lincoln tomorrow morning," I said, pushing away from the table. "So we have to spot that buck before very long."

The light was quickening in the east as we wound our way over the twisting Sand Hills trail, crossed the river on the rickety bridge, and drove into Federal land again.

Patch after patch of buckbrush was scanned, meadows glassed, and hilltops carefully scrutinized as the morning hours ticked away. By 11 o'clock we hadn't seen a hair, not even a fawn.

"It's beginning to look like we picked the wrong area," Les commented as we swung back toward the car.

"I can't argue with you," I answered dejectedly. "Let's give that range of hills to the east a going over before lunch."

The car seat felt more than comfortable as we jolted over the two-rut trail to the east. It had been a long morning and the leg work hadn't been easy.

Pulling the car into a draw, Les and I once again took to the hills. We had hiked less than a quarter of a mile when I suddenly caught a glimpse of something out of place along the hillside ahead.

"Hold it," I whispered. "There's a deer lying on that slope to the north near the ridge. Put the glasses on it and see if by chance it has a rack."

"It's yours, Gene," Les said excitedly, "but with the light coming right down on top of him, I can't tell for sure if he's more than a spike."

The animal had spotted us so we cut directly away from it, swung back up a valley out of sight, and eased over the hilltop into range.

About 300 yards separated us yet but with the flat-shooting .243 and the scope on 7X it wouldn't be to difficult to hit him if it was a Legal buck.

Both of us eased into sitting position, and I swung the scope until the cross hairs were dead center on the deer. I could see the long tapering spike but not the extra point to make it legal game.

"I think its a fork horn," Les offered, trying to keep his voice low. "It isn't a trophy, but with the time deadline, we'd better take him if it is."

The little buck lay watching as we stared into scope and glasses, trying to assure ourselves that he was shootable. My pulse began hammering in my ears, and my rifle wavered from time to time.

Finally he moved in his bed, stood up and turned toward the top of the hill to check his exit route. It was then that both of us saw the forkhorn.

"Take him, Gene. He has one jump to the top of that hill so don't miss."

The strain of holding the rifle on the deer caused the cross hairs to jump erratically, at least that's what I told Les as he urged me to shoot. What I didn't tell him was that touch of that well-known fever was on me.

Moving the hairs up over the hilltop I drew a

deep breath, came down until they rested just behind the shoulder of the little buck, and squeezed

24

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

the trigger. The 80-grain soft-point spat out at better than 3,500 feet per second, and I heard the sound

all hunters wait for as it "whumped" into the buck.

the trigger. The 80-grain soft-point spat out at better than 3,500 feet per second, and I heard the sound

all hunters wait for as it "whumped" into the buck.

The deer bounded about 20 feet, then sank to the ground. He was dead when I reached him. The shot had caught the deer just aft of the heart, but it had done its job well.

Les grinned happily. "You have just killed your first mule buck."

"Well," I replied, "he's not exactly the biggest deer in the country but he will far outdo some old boy when it comes to eating." Les' knife made quick work of the cleaning job, and we headed back for the ranch.

"Next year you'll have to try for one of the whitetails that hang out in the canyon," Les said. "I know of one old-timer down along Steer Creek Canyon that would make a swell trophy. The whitetails are more than holding their own along these canyons. Very few are killed since it's much easier to hunt the more plentiful mulies out in the open."

I left the ranch along toward sunset. As I topped out on the ridge I could look across the Snake to Steer Creek Canyon. There, silhouetted against the sunset, were three whitetails—two does and a buck. Even with glasses, I couldn't make out if this was Les' old-timer since he was screened by just enough brush to hide his rack. Perhaps next year I'll get a better look, I thought as I drove away.

THE ENDCLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 Dogs Registered Brittany Spaniel pups, wormed and vaccinated for distemper. Fine for pheasant and quail. Reasonably priced. J. P. Lannan, West Point, Nebraska.WAIT AND SEE

(continued from page 11)establish a new species in America. Before any of the thousands of quail were released by the 19 states and one Canadian province co-operating in the three-year project beginning in 1957, intensive research was carried out to determine, as far as possible, whether the coturnix could fill the growing need for a game bird that could survive in habitat that eventually might not support present upland species. Research indicated that the coturnix had a good chance of doing just that since it is adaptable to the short-grass environment that may be predominant in the future.

Thanks to the world's largest antelope trapping and transplanting operation, Nebraska hunters will soon be gunning the gray ghost in the Sand Hills. Its 20,000 square miles can support antelope without interfering with the cattle industry for which the area is known. The unique western trophy does not compete with cattle for available forage.

In recent years, Nebraskans have been introduced to such prized species as the walleye, northern, smallmouthed bass, and white bass. They may soon get a crack at giant muskellunge, warm-water trout, kokanee salmon, and redear sunfish. These, along with other varieties introduced, fill definite needs in the over-all fish management picture.

State fishermen drive hundreds of miles to tie into the fighting "muskie". In the process, they leave many dollars for other states to spend. Once this giant is established in the Sand Hills, he'll provide plenty of thrills right here at home. The muskie is a prime predator fish, and is just the ticket for keeping down pan-fish populations.

Eastern Nebraska anglers can tell you the value of establishing a trout that can withstand warm climes. Many a sand-pit lake and spring-fed farm pond could provide plenty of trouting if the new species lives up to advance billing. It is said that the trout can take 80° water without a whimper.

It's too early to say how the kokanee will do in Nebraska. This is the third year that the land-locked salmon has been planted in Lake McConaughy and Lake Ogallala.

Fish technicians have long looked for a variety such as the redear sunfish. It could be ideal for eastern farm ponds now from bluegill population problems. The redear, though possessing the same sport and table qualities as the bluegill, is more desirable since it is not as prolific.

There are eight new introductions—a prized big-game animal, prime upland-game birds, and needed fish varieties—our targets for the future. Maybe one or two won't make the long hard pull of taking up new residences in the state. Judging by present reports, however, Nebraskans will have a more varied bag, more opportunities to enjoy Nebraska outdoors, and, as in the case of pheasants, the chance to reap the bonus of a bountiful harvest.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 25

Notes on Nebraska Fauna

REDHEAD

Threatened ducks have strange habits. Hen builds a fancy nest of down but lays eggs anywhere. Drake flops head like rag, meows like catNO OTHER North American duck gets off quite so easily in homemaking chores as the redhead hen (Aythya americana). She often palms off her eggs to other ducks' nests.

But although the redhead disposes her eggs rather carelessly, she is an excellent home builder. The handsome nest can be identified with certainty even if no birds are nearby.

Fairly large ducks with round puffy heads, redhead males are easily distinguished from their close relatives, the canvasbacks, ring-necks, and scaup by their chestnut-red heads and upper necks. The vest is black; backs and sides are finely vermiculated with dark and white to produce a dusky gray effect. The tail and rump are black, breast and belly white with dusky tinge. The over-all effect of the male's body is darker than that of the canvasback. The hen is a nondescript brown duck, best identified by the company she keeps.

Easiest identification between the redhead and canvasback, on wing or water, is the profile of the head. The can's is classical, a gradual slope from tip of bill to top of head. The redhead's bill meets the forehead at a sharp angle. Much more like the scaup in general contour, the redhead can be distinguished in flight at a distance by the gray wing-stripe and more uniform coloring from the contrastingly patterned scaup.

Perhaps no other duck has decreased so rapidly

over the last 20 years as the redhead. This is because most of its breeding grounds lie where man

wanted drainage tiles, urban developments, and

wheat fields. The primary breeding range of the

redhead lies across the prairies of Canada and in the

western states from Utah and California east to

26

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Minnesota and Wisconsin. The species is a minor

nester in the Sand Hills of Nebraska.

Minnesota and Wisconsin. The species is a minor

nester in the Sand Hills of Nebraska.

These ducks are birds of the open water, and on the migration through Nebraska are to be looked for on our larger lakes and reservoirs. During the day redheads raft up in open water, sleeping and dressing their feathers. At this time the drakes are noisy, "meows" often issuing from the rafts in the "precise imitation of the voice of a large cat," according to Francis H. Kortright (1943). The major push of the autumn migration comes through Nebraska in mid-October, but the better-known routes lie along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

These ducks closely follow the canvasbacks from their main breeding grounds in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba eastward through the Great Lakes to the New England coast. From here they angle southeast to the Chesapeake Bay, then southward through the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf Coast. A third flight also courses down the Pacific Coast to winter in Mexico. A hardy duck, the redhead doesn't mind the cold, and may winter as far north as it can find open water.

The redheads migrate in Vees, and are among the faster fliers awing. Coming into a lake or reservoir, they reconnoiter the length of the water several times before selecting a feeding ground. But if they choose to tumble out of formation quickly, they can, zigzagging erratically, and it's every duck on his own.

Each morning and afternoon the ducks take their constitutional, promenading up and down the feeding area at a high elevation. Back on the water, they often boil up several feet into the air, settling back down again immediately. Like most diving ducks, they patter along for a bit before clearing water, but once on the wing are fairly rapid.

They're on their way north again by the middle of March, arriving at the breeding grounds just as the ice is breaking up. Courtship and pairing are delayed till then.

Courtship formalities are much like those of the celebrated canvasback, the male doing the same "headthrow". Like a limp rag, he tosses his head back until the crown touches his rump and his bill points to 10 o'clock. As he brings his head erect he gives the odd groaning call of courting season. After once selecting the territory, the female begins the elaborate nest.

The well-woven structure is made of reeds, deeply hollowed, and thickly lined with whitish down by the time all the eggs are deposited. It is this down that helps to identify the nest from the female canvasback's—the can's is grayer.

The eggs vary in number from 6 to 27, but the latter probably do not all belong to the present tenant. Redheads, like ruddy hens, indulge in promiscuous laying, both in other redhead nests and those of other species.

The redhead hen that tends to her own business usually brings off a clutch of 10 to 15 eggs. Incubation is from 24 to 28 days; during this time the drake abandons her completely to moult in the center of a large open-water area.

Successful fledglings feed on the surface for a week or two, then dive with the ease of adults. W. E. Clyde Todd (1940) writes of the drama when a hen and her brood sensed his presence. "The old one would flutter off in one direction with a great splashing of water, while the young scattered in the opposite direction and dived when closely pressed. They were rediscovered hiding among the aquatic vegetation, keeping beneath the water with only the tips of their bills exposed."

After about 2V2 months the young are able to fly. The hen has already left them to shift for themselves. is skulking in the reeds, flightless temporarily from a moult of her wing quills.

The food of the redhead is 90 per cent of vegetable origin, more than any other diving duck. The redhead will dabble with mallards for mollusks and insects, but is at its best in deep water bringing up leaves and stems of aquatic plants. The bird ranks as a top table duck.

Sportsmen may or may not gun the redhead again in Nebraska. The status of the bird is unknown; some feel that a lessening of the drought in Canada may ease the plight of the redhead and all other over-the-water nesters. Time will tell.

But there's more to be offered the outdoorsman than shooting, exciting as it is. The whistling wings of the redheads moving to their northern marshes is a part of the marvelous scheme of nature. To know they still belong is enough.

THE END NOVEMBER, 1960 27