OUTDOOR Nebraska

January 1959 25 cents Fishing Solid Water Pg. 3 Calling All Predators Pg. 6 State Trapper Pg. 22

OUTDOOR Nebraska

PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY NEBRASKA GAME, FORESTATION AND PARKS COMMISSION Editor: Dick H. Schaffer Associate editors: Pete Czura, Jim Tische Photographer-writer: Gene Hornbeck Artist: Claremont G. Pritchard Circulation: Phyllis Martin JANUARY, 1959 Vol. 37, No. 1 25 cents per copy $1.75 for one year $3 for two years Send OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, subscriptions to: State Capitol Lincoln 9 NEBRASKA GAME COMMISSION Floyd Stone, Alliance, chairman Leon A. Sprague, Red Cloud, vice chairman Don F. Robertson, North Platte George Pinkerton, Beatrice Robert H. Hall, Omaha Keith Kreycik, Valentine Robert F. Kennedy, Columbus DIRECTOR M. O. Steen DIVISION CHIEFS Eugene H. Baker, engineering and operations Glen R. Foster, fisheries Lloyd P. Vance, game Dick H. Schaffer, information and education Jack D. Strain, land management and parks FEDERAL AID CO-ORDINATOR Phil Agee (Lincoln) PROJECT AND ASSISTANT PROJECT LEADERS Orty Orr, fisheries (Lincoln) Bill Bailey, big game (Lincoln) Clarence Newton, land management (Lincoln) Dale Bree, land management (Lincoln) Malcolm D. Lindeman, operations (Lincoln) Frank Sleight, operations (Lincoln) Harvey Miller, waterfowl (Bassett) Raymond Linder, upland game birds and small game (Fairmont) RESERVOIR MANAGERS Melvin Grim, Medicine Creek, Carl E. Gettmann, Lewis and Enders, Swanson (McCook) Clark Lake (Bloomfield) DISTRICT SUPERVISORS DISTRICT I (Alliance, phone 412) L. J. Cunningham, law enforcement Lem Hewitt, operations John Mathisen, game Keith Donoho, fisheries Robert L. Schick, land management DISTRICT II (Bassett, phone 334) John Harpham, law enforcement Delmar Dorsey, operations Jack Walstrom, game Bruce McCarraher, fisheries Gerald Chaffin, land management DISTRICT III (Norfolk, phone 2875) Robert Benson, law enforcement Lewis Klein, operations H. O. Compton, big game George Kidd, fisheries Harold Edwards, land management DISTRICT IV (North Platte, phone 4425-26) Samuel Grasmick, law enforcement Robert Thomas, fisheries Chester McClain, land management DISTRICT V (Lincoln, phone 5-2951) Bernard Patton, law enforcement Robert Reynolds, operations George Schildman, game Richard Spady, land management Delvin M. Whiteley, land manager RESEARCH BIOLOGISTS Karl E. Menzel, coturnix quail (Lincoln) Marvin Schwilling, grouse (Burwell) AREA CONSERVATION OFFICERS William J. Ahern, Box 1197, North Loup, phone 89 Robert Ator, Box 66, Sutton, phone 4921 Cecil Avey, 519 4th Street, Crawford, phone 228 William F. Bonsall, Box 305, Alma, phone 154 H. Lee Bowers, Benkelman, phone 49R Dale Bruha, 1026 E7mar Avenue, York, phone 1635 Loron Bunney, Box 675, Ogallala, phone 247 Ralph L. Craig, Box 462, Chappell, phone 4-1343 Robert Downing, Box 343, Fremont, phone PA 1-4792 Lowell I. Fleming, Box 269, Lyons, phone Mutual 7-2383 Raymond Frandsen, P. O. 373, Humboldt, phone 5711 John D. Green, 720 West Avon Road, Lincoln, phone 8-1165 Ed Greving, 501 So. Central Ave., Kearney, phone 7-2777 H. Burman Guyer, 1212 N. Washington, Lexington, phone Fairview 4-3208 Larry Iverson, Box 201, Hartington, phone 15F120 Norbert J. Kampsnider, 106 East 18th, Box 1, Grand Island, phone DUpont 2-7006 Jim McCole, Box 268, Gering, phone 837 L Jack Morgan, Box 603, Valentine, phone 504 Roy W. Owen, Box 288, Crete, phone 446 Paul C. Phillippe, Svracuse, phone 166W Fred Salak, Box 152, Mullen, phone KI 6-6291 Herman O. Schmidt, Jr., 1011 East Fourth, McCook, phone 992W Harry A. Spall, 820 Clay Street, O'Neill, phone 637 Joe Ulrich, Box 492, Bridgeport, phone 100 Lyman Wilkinson, R. R. 3, Humphrey, phone 2663 Richard Wolkow, 817 South 60th Street, Omaha, phone Capital 1293 Don J. Wolverton, Box 31, Rushville, phone David 72186 J. B. Woodgate AlbionIN THIS ISSUE:

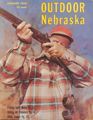

FISHIING SOLID WATER Page 3 (Gene Hornbeck) CALLING ALL PREDATORS Page 6 (Jim Tische) WINTER CAMPING CAN BE FUN Page 8 (Pete Czura) HOW TO BUILD A WEATHER VANE FEEDER Page II (C. Paul Denckla) WILDLIFE TRACKS Page 12 (C. G. Pritchard) GAVINS POINT Page 14 (Pete Czura) PHOTO NEWS Page 17 HOW DOES A FISH SWIM? Page 18 (David Gunston) THE SHOT THAT KILLS TOMORROW Page 20 (Gene Hornbeck) STATE TRAPPER Page 22 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE Page 25 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA (Porcupine) Page 26 (Jim Tische) MATCH 'EM UP Page 28GUN bugs have a new and fascinating hobby in muzzle-loaders. This pleasurable hobby has been captured on film by staff photographer, Gene Hornbeck, for this month's issue of OUTDOOR NEBRASKA. The shooter is Randolph Horsley of Lincoln. The old-time guns are becoming popular as mantel pieces and for use in the field. This hobby offers a challenge to the hunter to fill his game bag with the weapons of another era.

FISH THE SOLID WATER

A bit of string, a tiny stick, some bait, warm clothes, and you're in as a "frostbite" angler by Gene Hornbeck Photographer-WriterIF you continually crave for new outdoor adventures in the Cornhusker State, then this article is designed especially for you. Some Nebraskans have tried ice fishing, but they are so few in number that they can be considered pioneers. I recently began investigating the opportunities available here for ice fishing and found, as is true in summer, that much of our fish population goes for naught. We are taking but a minute percentage of the harvestable fish.

Perhaps, I can lay down some simple rules for ice fishing and a winter fish habits that will kindle the flame of that semidormant fishing fever. To become a successful ice fisherman, you should first know the fish that you are seeking.

When winter covers our lakes with its handiwork,

some interesting changes take place in the habits of fish.

The catfish, bullhead, black bass, and white bass, to name

JANUARY, 1959

3

a few, become inactive, almost to the point of hibernation.

But there are a number of species that feed actively

through the winter months. Some of them appear to hit

better than they do during the dog days of summer.

a few, become inactive, almost to the point of hibernation.

But there are a number of species that feed actively

through the winter months. Some of them appear to hit

better than they do during the dog days of summer.

The winter favorite of many Midwest anglers is the yellow perch. This fine panfish inhabits many of our Sand Hills lakes and the reservoirs of central and southwest Nebraska. The perch is active all winter, and baits which work well include live minnows—in the one to two-inch class—corn borers, meal worms, and goldenrod grubs. My favorite bait is fish eyes on a tiny jigging spoon. The eye is tough and if the fish are schooled, as they usually are, I can take a dozen fish before changing bait. When using grubs, I prefer the small jigging spoon as it adds the little flash that creates strikes.

Another fine target for winter angler is the bluegill. Very seldom taken on minnows, the bluegill prefers small grubs. The tiny goldenrod grub, impaled on the hook of a small spoon, is one of the best. Corn borers and meal worms on a small hook are close seconds.

The crappie, also a winter battler, prefers a lively minnow. Larger fish, the northern pike and walleye, will take a minnow with regularity. Minnows are about the only bait available in winter that will take the larger game fish. Hook your minnows through the back, just under the dorsel fin, so they swim in an upright position. One other rig I have used with satisfying results is the jigging stick and spoon, sometimes referred to as the ''Swedish Pimple."

A word on finding winter baits. Minnows, of course, can be procured from a dealer. Goldenrod grubs are perhaps the easiest to find, on your own. Search through a goldenrod patch until you find one with a knot or growth called gall, on the stem. It is here that the grub is found. If there is no hole in the knot, the grub is still intact. Cut the knots off with pocketkinfe and go on checking other stems. Leave the grubs in their natural containers and cut them only as bait is needed. Keep the galls outdoors when storing, and you will have a fresh bait supply.

Corn borers, found during winter in corncobs and stalks, shouldn't be too hard for most Nebraskans to gather. A small hole bored in the cob or stalk is the sign to watch for. Cut the hole open, remove the grub, and place it in a small ventilated jar filled with shredded husks or similar material. Meal worms, a little harder to come by, are often found in large numbers in graineries, elevators, and mills. A forgotten pile of grain swept into a corner may be alive with them. Store the worms and grain in a jar for your next fishing trip.

Another worthy bait is the wax worm, found to some extent in most bee farms. This tough bait can be kept in sawdust or the like, in a cool place, for long periods.

In the artificial line for panfish, there are a number of small spoons and weighted flies which are productive when used with a light, limber jigging rod.

Perhaps the most common equipment is a short stick, hook, line, and sinker, floated by a cork to indicate a bite. This outfit is adequate to take some fair catches, and I find that it works best on perch and small walleye and northerns. These species usually take the bait by striking rather than nibbling as do crappie and bluegill.

My ice-fishing choice is a light, limber jigging rod loaded with monofilament line that is weighted with a large split-shot for minnow flishing and a cork just large enough to float the terminal rig. When jigging with a tiny ice-fishing spoon or fly in fairly deep water, I use a very small splitshot. In water under 12 feet, I use the rig without any weight because it gives the lure better action as it flutters lightly downward through the water. A tiny quill float is a big advantage, indicating the nibbling of the bluegill and crappie.

When using a limber jigging rod, a slight jigging action of the bait will consistently produce better results. This is especially true of fishing the tiny spoons, ice flies, and small grubs. When using the term slight, I mean move the rod tip an inch or two in a twitching movement, rest it a few seconds, twitch again, rest, and so forth until your cork goes plunging out of sight.

Ice fishing for northern pike and walleye is rewarding, but it takes a lot more time and the action is slower than fishing for panfish. One of the best all-around rigs for northerns and walleyes is the tipup. Nebraska law allows the angler up to 15 hooks in the aggregate. With this many hooks, the tipup really becomes a potent fish catcher. Your tipups can be rigged with one or two hooks, and you can use as many as you can punch holes for and tend—within the legal hook limit.

Angling for these big fish in winter can be more advantageous in some areas than in summer. In winter you can place your rigs in different depths and areas simply by walking over and cutting a new hole.

What about lines? First, in the panfish rigs, a 6 to 10-pound-test monofilament fits the bill if fishing in less than 20 feet of water. In depths up to 60 feet, try a heavier line, either monofilament in about 20-pound-test or a cheap fly line with about three feet of leader. The reason for heavy line in deep water is obvious to those who've tried a lighter line and found a frozen "bird's nest" piled on the ice after landing the first fish. Heavy line lays in larger coils and does not pick up the water as does the braided casting line or chalk cord.

Where and when do you fish in the winter months? It is a good policy in all ice fishing to start about a foot or two off the bottom and if the fish aren't biting come up one or two feet at a time.

Yellow perch are usually in the moderate to deep

waters. Bluegill and crappie will under most conditions

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

be found in shallower waters. This is especially true in

larger, deeper lakes and reservoirs. Walleye follow much

the same pattern as the perch, and are found in deep

water. Northern pike, on the other hand, often frequent

the shallows and many times are hooked in less than 10

feet of water.

be found in shallower waters. This is especially true in

larger, deeper lakes and reservoirs. Walleye follow much

the same pattern as the perch, and are found in deep

water. Northern pike, on the other hand, often frequent

the shallows and many times are hooked in less than 10

feet of water.

In fishing any lake, it will pay you to first ask other anglers there how they are doing and where they have been catching fish. Local townspeople, too, will have information you need.

Before chopping your holes in the ice, look over the lay of the land surrounding the lake. If there is a ridge, point, or peninsula extending into the like, begin there. Depending on the species you are seeking, start in shallow water and continue out uritil you hit fish or maximum depths.

If you should find a heavy weed bed, try working out until you hit its outer edge. Such an area is especially productive for northern pike. If the edge of the weeds is in depths of 10 feet or more, it will also be a good spot for crapie and bluegill.

The time of day to fish is as variable in winter as in summer. All things considered, the early morning hours are usually the most productive on all species.

Where do Nebraska ice anglers ply their sport? Some of the major areas include McConaughy, Harlan, Medicine Creek, and Swanson reservoirs. Lakes such as Big Alkali, Medicine, School House, Smith, Minatare, and Whitney are gathering a small following of "frostbite" fishermen each year.

Many of the farm ponds throughout the state supply bluegill galore to summer fishermen and should provide lots of action, too, for the winter angler. Any area that offers good summer fishing is worth a try in winter.

Your ice-fishing gear should include a good ice chisel, called spud, preferably one with an all-metal handle for extra weight. The light chisels are hard to cut with. You also need strainer to dip chipped ice out of the hole. You can buy one or you can make your own by punching holes in a coffee can with a nail

When it comes to transporting your gear across the ice, nothing beats Junior's small sled, fitted with a box. If you wish to make a fancier outfit, the box can be made to fit your collection and then add a ski or toboggantype bottom.

Clothing should of course be warm, and the insulated clothing and footgear now on the market are ideal. For the real cold days, wear a pair of rubber-treated gloves as they stay dry even When handling wet lines and fish.

If you really want comfort on the ice, why not build a three-sided windbreak? Or if you want a permanent adobe on some good fishing spot, build a fishing shanty. Any inexpensive material will do to cover a framework. Pressboard, for example works fine when tacked over a 2x2 studing. Canvas or heavy cardboard will also do. Make the shanty big enough so three or four people can sit comfortably. A six-foot square shanty is minimum size, mounted on a 2x4 runner to facilitate easy moving to better fishing areas.

Place wooden benches against each wall, and cut the fishing holes in front of each seat. A small stove makes ice fishing a real joy. A heavy five-gallon paint can makes a good stove. Cut a vent about six inches long and four inches high on the side of the can near the bottom and hinge it to make a door. Clamp the lid down tightly and cut a hole to take a piece of three-inch stove pipe. Vent the pipe to the outside of the shanty.

Although the supply may be limited, some of the larger appliance packing boxes, such as refrigerator cases, make serviceable fishing shanties. You should have at least two of them, joined together. If you don't mind getting on speaking terms with the friendly undertaker, he sometimes has a few packing crates on hand—the ones he receives the coffins in. They are well made and larger than most appliance packings. Two of these serve as a roomy fishing shack for two people.

Nebraska has only one law covering the use of shanties, and this applies to Lewis and Clark Lake and the Missour River. The law states that any fishing shanty placed thereon must have the name and address of the owner clearly imprinted on it. Perhaps there will never be any further restrictions, providing each fisherman uses good judgement in placing his shanty and making sure he removes it before the ice melts in the spring.

A man can enjoy outdoor Nebraska in winter just as he does in summer and fall. Snug and warm in a fishing shanty or braving the elements in the open, he can listen to the booming of the ice as it groans and shifts. And out in the open, he can rub frost-nipped hands between catches, clear the scum off his holes, and keep busy cutting a few new ones.

So this winter, when out on some ice-locked lake, doing a jig to keep the bite of cold out of your boots, and you see another fisherman coming your way, don't stop the dance, friend. I'll whistle the tune and join you, because that's ice fishing.

THE END

CALLING ALL PREDATORS

by Jim Tische Associate Editor Here's a different approach to fun and sport in the outdoors: Pick the right spot and try squealing like a rabbit in distress. Then watch for the pay-offTHE long, high-pitched, agonized wail of a "dying or trapped" rabbit echoed down the hill and into a tree-covered vale, and then all was quiet. Six, seven, and then eight times, the piercing cry screamed out, and then silence again.

Ten or 15 seconds later, another series of calls went out. Then another short breathing spell, followed by the screams of distress. The same routine was repeated for 8 or 10 minutes.

The highly specialized kind of music that was wailed out over the hillside is associated with one of the newest hobbies to sweep the country in recent years. It is part of predator calling. This particular brand, using the sound of a distressed rabbit, is aimed at foxes and coyotes, but will also work on owls, hawks and raccoons. It has been known also bring in bobcats. All these potential targets inhabit this state.

This sport is for the man who loves the outdoors. It takes no special talent, just time and patience. Sometimes, it doesn't even require much time. Bryon W. Dalrymple, writing for a national sports publication, says:

"In the Southwest last year I bought a coyote call, read the directions, went to the desert. I sat on a rock above a mesquite-bordered dry wash, blew a series of wails imitating a rabbit in distress. Within minutes a big dog coyote came bounding around a crook in the wash, hackles raised and eyes burning. I have witnessed as many as five racing simultaneously toward a caller. Exciting business, this."

6 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Of course, predator calling won't always be this easy. There may be many dry runs before you call up a coyote or fox. This only goes to show the unpredictability of hunting, even with a call.

Everyone—young or old, male or female—can try predator calling. As I said, it takes no special technique and is a hobby which can be practiced with little equipment.

Hart Stilwell, nationally known writer, tells in another sporting magazine that "It's not too hard to imitate the squeal of a rabbit in distress, which interests almost all predators. Draw the lips in fairly tight between the teeth, leaving a small opening on one side—not in front. Cup your off hand over your mouth so that your forefinger is above the opening and your middle finger below it. Then suck in hard. You can vary the pitch by the size of the opening.

"If you can't get onto the trick," he continued, "get one of the calls now on the market. Almost all of them will bring game, and they have one advantage over the natural call—volume."

So for most beginners, the first thing is to acquire a call. Sporting-goods stores carry the different calls, ranging from $2 to $100 each. Calls, which are blown, are made of wood, others of rubber, still others of plastic.

All beginners would do well to study the sounds of the calls on a phonograph record. Some records also give give calling instructions. It is difficult to put down in writing precisely how to use the different calls. The wax disc will do the job better and will also serve later as a reference or refresher course.

The best time to try for a fox is in the evening, as he leaves the den to search for food. Most experts claim the fox will respond to a night call like a crazy creature, barging right in and sometimes almost running over the hunter. A fox will also come in moderately well in early morning and late afternoon.

Why is the fox a good target for predator callers? For one thing, Reynard has very little trouble living with civilization, sometimes right in or near large cities. He likes the brush fringe, boarding on marshes, tilled fields, and pastures.

For your adventure, pick a day or evening with little or no wind, for the tantalizing sound of the rabbit will carry much better then. Select a spot where you have a good view of the landscape, and where the best fox cover is downwind. If a fox catches your scent, he will not dance to your Pied Piper wail.

In night calling, it is not necessary to hide. You will however, need a battery or carbide headlight. Such lights leave the hands free for handling a gun or bow. Select a clearing, the middle if surrounded by trees, turn on the lights, and start calling. If there are two or more in your party, stand back to back so that the lights will cover the entire watching area. Only one person should call, as each caller has a different tone to his wail.

Keep the headlights on at all times while calling. These should be pointed to the tops of the trees or defused to give a soft light; a strong beam will scare the fox. As the fox moves in, you'll be able to see his eyes shining. When the animal is in shooting range, one of the lights is put directly on him and you have your shot.

While cover is not; necessary for night calling, it is essential during the day. Clothes should be such that they will blend with the landscape. Use natural foliage for a blind, and supplement this with branches or clumps of grass. Fallen limbs, weeds, and even a big tree will serve as cover for the daytime call.

Once in the blind, be as still and quiet as possible. Reynard is alert, wary, and has keen eyes, ears, and nose. You can spook him with the slightest of movement or noise.

Concealment is also necessary on bright moonlight nights. Squat or kneel down near weeds, trees, stumps, or small bushes so that you aren't outlined against the horizon.

Now for calling. Different methods of calling in predators have been tried once one has been spotted. When the call was give fast and furious, the fox responded in the same way, racing to get to the rabbit. If the call was sounded a few times, followed by long intervals of silence, the fox responded slowly. He would move in while the call was going, and when the call stopped, the fox also stopped apparently to listen for more calling.

When a caller starts at a new spot, he should put maximum volume in his call. You should blow easy, harder, and then easy all in one breath. The loudest squeak should be in the middle of the call. The longer you call at the spot, the softer the cry should be, so the animal will move closer in.

Some hunters have had dangersouly close calls with owls and hawks. These two birds will decoy to the sound. Apparently seeing nothing but the hunter's hat at night (probably taking it for a rabbit), and following the sound, they will swoop down on the caller. There are reports of callers losing their hats and even getting hit by a bird.

Predator calling is by no means restricted to shooters. Photographing "called" animals is catching on as a popular sport. This sport is taking its place in our life as an outdoor diversion which offers fun and a challenge.

Again, don't be discouraged if you fail to get a fox or coyote on the first try. It took me several nights to score. There will be days when the animals won't budge at all, and then, too, there will be times when they will try to run over you.

But one thing is certain: Once a hunter successfully calls a predator, his goose is cooked; he'll be busy calling every chance he gets.

THE END JANUARY, 1959 7

WINTER CAMPING IS FUN

by Pete Czura Associate Editor Who cares if cold winds wail and snort? Not you, not if you follow these rules; you should be snug as a bug in a rugWINTER camping is not an ordeal that only the tough can enjoy. In fact, winter camping has become extremely popular and ranks with other winter sports. And with modern camping facilities and comfortable gear, some campers have become as addicted to this form of activity as golf bugs have to golf.

The tales that you can sleep in a sleeping bag out on the snow, without a fire, and enjoy yourself at below zero, or that you can wrap yourself in a single roll of blanket and enjoy sleep at such temperatures are idiotic to say the least. However, during the coldest spell of sub-zero weather, if you prepare yourself properly, you can sleep in absolute warmth and comfort, and enjoy good wholesome meals to boot. Why not give winter camping a whirl?

Just as in any other sport or venture, there are some things to do and not to do. The secret of comfortable camping is to wear as little clothing as possible during any physical activity, so as to lessen excessive perspiration. A typical outfit would include long, insulated two-piece suit of underwear; pair of heavy all-wool socks; wool pants; light wool shirt; thin poplin parka wind breaker with fur-trimmed hood; knit cap that can cover your ears; sturdy mittens, and rugged, insulated all-weather boots.

Above all avoid wearing any garment that will constrict free and easy movement of your body. Tight clothing strangles circulation and speeds up the process of becoming cold. The mark of a greenhorn sticks out a mile on anyone who dares to winter camp dressed as a Beau Brummell. Smartness of attire is fine, but your first consideration of any piece of clothing is its usefulness and utility in the wilderness.

Out in the field, and as the weather warms up, remove some of the outer apparel, but keep moving. The moment you stop, don your outer garments to prevent any chilling of your body. It's a good policy to tote some extra socks, mittens, and long underwear in case of an emergency, too.

Get good insulated lightweight boots suitable for snowy conditions. The Korean boot, which is all-rubber and insulated, is fine. Leather boots can become ice-box traps for your feet in case the ground becomes extremely damp. They'll get wet and cold and remain so for a long time. However, under dry conditions, leather boots are O.K.

A word about drying your foot gear. Don't rush the drying process, like putting them near a fire. Let them dry naturally. Fill them with warm rocks or pebbles, or invert them over a stake. Never oil or grease any kind of rubber boots; they'll deteriorate.

There's nothing like a warm meal to revive flagging spirits. Make sure you take along items for hot meals. Soups, stews, and hot coffee, tea, or cocoa are fine. You'll enjoy the instant soups and drinks, for they are easy to prepare, requiring only hot water.

8 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Avoid taking any food in glass containers; they'll freeze and crack from expansion. Canned goods are preferred, and they can be heated easily. Place can in a pan of warm water, or on a stove. Heat canned goods gradually. Make sure the stove is not red-hot, else the sudden change in temperature may rupture the can.

A good way to keep your food from freezing is to wrap it in a waterproof container and bury in the snow. The temperature below the snow may be higher than on the surface. Mark spot with a long stick so in event of a heavy snowfall you can locate your cache easily.

In case your meat freezes, try cutting it the easy way—with a saw. Still better, cut your meat into the desired portions BEFORE you leave home. However, if you relish chipped beef, use the chopping method but watch out for flying bits of frozen meat.

If your water supply dwindles, melt snow or ice. Both are safe. Remember, there's a difference in volume. With a bucketful of snow you'll be lucky, when you melt it, to get a cupful of water. A pail of ice, however, will furnish you with almost a full pail of water. A two-quart pail is usually large enough for most camping outfits.

When it comes to tents, it is imperative that you select one made of fairly rugged material, capable of withstanding rough use. For instance, if you're camping out and a sudden snowstorm hits, you can brush off the snow with a branch, or punch it loose from inside your tent without any fear of tearing your tent.

Cramped quarters are not conducive to happy camping, so get a tent that is large enough. Allow space for a tent stove. Remember, too, you must provide a tent opening for a stovepipe; an asbestos stovepipe sheeting should be used at the opening to prevent the danger of fire. In summer, simply cover this opening with a spare piece of canvas.

Felix Pogliano, a nationally known outdoor writer, says: "If you're ever caught in a situation where you are without your tent and stove, camp out in lean-to style. This is one way of camping that deserves the term, roughing it. This type of camping should be reserved for emergency bivouacs, unless you want to prove to yourself that you can survive "Operation Frigid" in weather that would freeze the tail off a brass monkey.

"Here you must rely on the reflector fire to shower warmth into your lean-to. Make a fire about five feet long and set your sleeping bag so you can lie parallel to the heat. Be sure to gather plenty of firewood because you'll be feeding that fire often during the night. And above all, locate your cozy nest on the lee side of a big rock, or in cozy grove, where the wind can't dissipate the reflecting heat."

Some stoves can be used for preparing simple meals,

and will keep you warm and comfortable while a blizzard

rages outside. Costs of stoves vary from $5 to $10. That

old stand-by, though, the Sheepherder stove, can cook

and bake enough for a banquet. Though these cost around

JANUARY, 1959

9

$25, they are really life-time investments and are worth

the money.

$25, they are really life-time investments and are worth

the money.

With a certain amount of precaution, your tent stove is usually safe. Set your stove on piece of asbestos cloth for added insurance. In case of a tip-over, you can smother the fire with the cloth, or use it to set your stove up again.

Don't worry if your tent becomes covered with snow. This will help to keep you warm. In time, a stove will melt the snow on your tent, causing a run-off to the bottom of your tent, and may freeze. When this happens, don't chop your tent loose. Avoid risking injury to your tent by using hot water to melt the ice.

A good all-round sleeping bag is a must for the winter camper. Still, though, it alone is not sufficient to ward off the cold wintry blasts, so use some insulating material underneath it. A good combination is an air mattress below and a couple of top-notch woolen blankets, either in or on top of the sleeping bag. Wear fresh, wool or cotton socks when you hit the sack. These will add immeasureably to your sleeping comfort. And a knitted stocking cap for your head and ears will come in mighty handy, too.

A good idea is to obtain a sleeping bag with snaps. Zippers have been known to jam, and in an emergency could trap you inside the bag. With snaps, you can explode out of the bag when you have to.

Before going to bed, change your underwear. Hang it along with the other garments you've removed in the ceiling of your tent, or on the rafters of your cabin. They'll be nice and dry and warm, too, by morning.

Once your hands and fingers become numb from the bone-chilling cold of a winter day afield, you'll have a hard time enjoying your trip. Old-timers in this game wear mittens, on a cord wrapped around their neck. For real cold-weather comfort, wear gloves inside the mittens.

There are several ways of transporting your gear to camp. One is to carry it on your back. Another is to pull it behind you on a toboggan or sled. Third is to use horses, and the fourth is via auto. The easiest way, of course, is the latter, if the roads are passable. Hauling your gear in this manner, however, deprives you of the pleasure of toting your outfit through the hinterlands and enjoying the scenery first-hand.

If you carry your outfit, you will probably use one of the following: packbasket; packsack; waterproof packbags; packcloth; tumpline packs or a duffel bag. Of these, the packsack is the most popular among winter campers. However, all have certain advantages. The packsack is roomy and its mouth is big and easy to open and close. It will usually carry all that an individual will need, and if the sleeping bag is too bulky, it can be strapped easily on the outside. A good idea for the fellow who packs his packsack to the bulging point is to have the flap extended six to nine inches, making it easier to close.

Be careful when packing your gear. The most common fault is to stuff too many small, unnecessary items into the packsack. This results in confusion, broken containers, and damaged equipment. Make it a habit to stow your gear neatly, and you'll be amazed at how much you put away, if you try.

Eyes, too, need consideration in winter camping. To prevent any damage to them be sure to pack a pair of smoked glasses. The intense glare of the brilliant sun on snow can cause snow-blindness. In a pinch, carve a piece of wood to fit across your eyes and cut two slits, one for each eye, in it. Attach a piece of string or a rubber band to each end and slip over your head. The sun's glare is reduced immediately.

Of all the items included in your winter camping gear, the one tool you should never forget is the axe. This piece of equipment is indispensable, and its ability to perform a myriad of jobs around the camp makes it a must. For easy packing, the small belt axe fills the bill as jack-of-all-trades.

Under miscellany comes a multitude of items. Knives, compass, maps, toilet articles, first-aid kit, emergency repair kit (one that can be toted in a typewriter ribbon can), etc. Make certain that each item you pack is essential to your comfort, welfare, and safety.

Try to make it a point to visit the state parks and recreation grounds. These are plentiful and are well distributed, so the camper may choose his routes and camping schedule with confidence that he will always be within short driving distance of another camping site. Brochures listing these different areas are available on writer request to the Game Commission. Ask for "In Nebraska."

What you will see and how you will fare on your first winter camping expedition will depend entirely on you, and how you prepare yourself for the outing. One thing for sure, though, you're in for the time of your life.

THE END

HOW TO BUILD A Weather Vane Feeder

THE PURPOSE of a weather vane feeder is to offer protection to birds from the elements while feeding, and to prevent the feed itself from becoming damaged or otherwise spoiled by rain or snow. The open end of such a feeder is always pointing away from the direction of the wind, and is further protected by a wide overhanging roof section. It is suggested that the end of the feeder facing into the wind be made of glass or plexiglass to permit additional light to enter the feeder. Painting the interior white will also be advantageous.

It is important, in constructing a feeder of this type, that it turns in the slightest breeze. Otherwise, its effectiveness is lost. Drawings with this article show a simple, economical, and effective means of constructing such a feeder, one that will pivot in a breath of air. Probably the most important consideration in completing the feeder is establishing the pivot point prior to assembly of the bearing or turning mechanism. This can easily be done by balancing the feeder lengthwise on some sharp edge, such as that of a wooden ruler.

Only after this balance point has been determined should the reinforcing plate—counterbored for the one-half inch washer—be fastened into position. After the washer is seated into the wood, it is a simple matter to assemble the other components of the mechanism as shown by the drawing. Before final erection of the feeder it is suggested that some light grease be put into the brass tube for lubricating the ball bearing and lateral bearing surfaces.

I suggest the box section of the feeder be made of a surfaced cypress, and finished to three-quarter-inch thickness. The wood should be well treated with a preservative, then stained to the desired color tone. Finally, it should be given three or four coats of Valspar varnish. Brass screws, 1 1/2 inches long, should be used in assembly, in No. 8 or 9 sizes.

The feeder shown here has been used for the past five years and continues to respond to winds of the lowest velocities. Such feeders can be made slightly larger than the one shown, but I do not recommend they be made smaller. This one will conveniently hold about two quarts of grain, and is constantly used throughout the year by many species of birds.

THE END

WILDLIFE TRACKS WHAT THEY TELL

KNOWING animals and their tracks is part of the fun and excitement that comes with the great outdoors. It is an ancient science which was put to use with remarkable skill in early times, helping man gain a living in the wilderness.

Now it has turned into a fascinating pursuit which can be a hobby or aid in hunting. With a knowledge of the markings left by a creature of the wild, you can read a record in the dusty trail, the woods, a cornfield, river bank, or snow-covered prairie.

With a careful study of these tracks

in OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, you will

be able to readily identify most animal tracks you find.

Another set of winter tracks, drawn by staff artist Bud

Pritchard, will appear in the February issue. Study them.

See, if they don't add to the thrill of communicating

with nature.

be able to readily identify most animal tracks you find.

Another set of winter tracks, drawn by staff artist Bud

Pritchard, will appear in the February issue. Study them.

See, if they don't add to the thrill of communicating

with nature.

Tracks will tell who lives in the woods and who runs wild and free on the prairie. Also, who lives and travels near the river banks or lake shores. This captivating pastime can open a whole new aspect of the outdoor world in just a short time.

Wild animals are shy and try to avoid man. Many are nocturnal and seldom seen. Knowledge of tracks will disclose the animals you didn't see. There is a story behind the tracks in the wild, and study may reveal much about the animal in relation to its habitat. Reading tracks will add new language to your repertoire.

THE END

GAVINS POINT

by Pete Czura Associate EditorIF you haven't as yet been a visitor to Gavins Point Reservoir, on the Nebraska—South Dakota border, you are missing one of the Midwest's most spectacular recreation areas. When the opportunity to go there presents itself, don't go alone, for there's something in the way of outdoor adventure and fun for the entire family.

Gavins Point Dam is a rolled-earth structure extending almost 10,000 feet across the mighty Missouri River, forming a fabulous lake named Lewis and Clark. The dam is 74 feet high, 35 feet wide at the top, and 800 feet thick at the base. Operating as a unit in the system of main-stem reservoirs, Gavins Point controls floods on the Missouri River from Yankton, South Dakota, to the mouth of the river above St. Louis, Missouri.

The powerhouse is an imposing concrete structure built on the Nebraska side. Its power-generating facilities are housed in reinforced concrete. Three 33,333-kilowatt generators give the plant a rated capacity of 100,000 kilowatts. The intake structure is integral with the power plant. Water passes through the intake directly to the turbines. The head, or drop, from the surface of the reservoir to the river below is 45 feet.

The spillway, located on the Nebraska abutment of the dam, is of concrete construction. Working as a safety valve, it prevents floods from overtopping the embankment. Fourteen tainter gates, each 40 feet wide by 30 feet high, are located on the 560-foot-long spillway crest to control the flows. Discharges flow down the spillway chute into the stilling basin where the energy of the water is dissipated. From here the flow returns to the main channel of the river.

The Lewis and Clark lake extends 37 miles upstream, ending near the mouth of the Niobrara River. It reaches

14 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

three miles in width and has 33,000 surface acres of water. Possessing over 100 miles of rugged shoreline, the Lewis and Clark lake is padded with native cottonwood, willow, pine, poplar, and oak trees. Add the majestically crusted, sheer chalkrock bluffs and you have a scene of magnificent grandeur.

To learn what this area offered in the way of recreational facilities, prompted my trip to Gavins Point in early December. Carl Gettmann, reservoir superintendent for the Nebraska Game Commission, personally conducted me on a tour of all the recreation sites. Carl also briefed me on the future plans of the Game Commission for improving this area.

We noted, that because of its picturesque shore line, made up of rugged, jagged cliffs and partially wooded slopes, the Lewis and Clark lake area is well adapted to all types of outdoor recreation.

Fish and wildlife abound here. Motor-boating, sailing, and swimming enthusiasts have made this area one of the state's hot spots. Picnicking, camping, fishing, huntting, and hiking activities are all available here. This magnificent area can be reached from any part of the state in eight hours or less of leisurely driving.

If you drive from the east and south, your best bet is to take state highway 81 north. From the west and southwest, take U.S. 20 or 30 to 81 and head north.

There are 12 recreation sites on the over-all area. Only four, though, have been developed to date for use. There are Cottonwood, Training Dike, and South Side tail waters; South shore; Weigand boat basin, and the Niobrara area. All these contain fireplaces, picnic grounds, camping facilities, picnic tables, benches, and refuse receptacles.

My tour began with area No. 1, which is comprised of the Cottonwood, Training Dike, and South side tail waters. All of these are near the dam.

The Weigand Boat basin, located 5 miles by boat, and 10 miles by auto west of the dam, contains a public concession stand where groceries, sandwiches, lunches, candy, ice cream, fishing tackle, boats, motors, and water skis are available. The basin has a rental space for over 100 boats, lots of parking facilities, and an excellent swimming area. A tree planting program, instituted by the U. S. Corps of Engineers, has pine, cedar, maple, cottonwood, Russian olive and thornless locust growing in the area. Access to popular areas such as this is by good roads, all well marked for easy driving.

The Cottonwood, Training Dike, and South tailwaters areas provide boating, fishing, picnicking sites, and fireplaces—with lots of firewood available. The Training Dike site has a clear, sandy beach for swimmers. According to Ansel Petersen, Corps of Engineers, reservoir manager, "This area contains an unlimited potential and already offers many delightful hours of recreation for young and old alike."

Of the above mentioned areas, the South side tailwaters is preferred by fisherman. This area has a sloping sandy beach, boat ramp, and ample boat-launching facilities.

Make sure to visit the two spectacular look out views.

These are easy to find by way of well-marked roads

and trails. From these high vantage points visitors get

an awe-inspiring panoramic view of the enchanting lake

JANUARY, 1959

15

and the rugged bluffs guarding the shore line. The east

look out has a view of the tail waters, powerhouse, and

spillway. From the west look out which many consider

the best, is a view of the back side of the dam, powerhouse, and the entire lake as far as the eye can see.

and the rugged bluffs guarding the shore line. The east

look out has a view of the tail waters, powerhouse, and

spillway. From the west look out which many consider

the best, is a view of the back side of the dam, powerhouse, and the entire lake as far as the eye can see.

The entire recreation area from Gavins Point Dam westward, over 1,200 acres in all, is state—managed. And if you are wondering how popular this area is, check the figures. In 1957, first year of operation, the dam attracted 925,000 visitors. In 1958, up to November 1, over 1,250,000 visitors poured into this area for fun and pleasure.

"It's a shame," commented Gettmann, "that more people don't take advantage of this area in early spring or late fall too. Outdoor pleasure seekers seem to think that Memorial Day opens this area and Labor Day closes it. Northing could be more wrong.

"Many Nebraskans," he continued, "are missing a good bet by not coming here when our recreational facilities are not taxed to the limit. However," he pointed at some moored boats, "our boaters are learning quick; they're leaving their boats here well into December."

In talking with Petersen, I asked, "How does fishing stack up here?"

"I wouldn't recommend ice fishing on the reservoir, as the lake doesn't freeze up too solid," he answered, "but the boat basin, below the dam, is OK. During the rest of the year, anglers can catch sauger, catfish, drum, bass, northerns, and paddlefish."

Fishing permits from both Nebraska and South Dakota are honored by the respective conservation departments anywhere on Gavins Point reservoir. A fisherman with a Nebraska permit cannot, however, fish from the South Dakota shore line, and vice versa.

A huge federal fish hatchery, under construction just below the dam will propagate fish to supplement the present population. Warm-water species like catfish, walleyes, bass, and northerns will be stocked in large quantities. Also, trout plantings will be attempted later to provide angling for the avid purists.

Angling hot spots in this area are: Tail waters, best for year-round angling; Santee, opposite Springfield; Bon Homme bottoms, which has an excellent cove; Devil's Nest, opposite Bon Homme for bass and catfish. Veteran fishermen recommend the areas below the commorants nests, where fish flock; Sand Islands for bass, catfish, and crappie (between sand bars).

The use of boats on the reservoir must conform to

all federal, Nebraska and South Dakota laws and regulations. All boating is under the supervision of the U. S.

Coast Guard, with checks made frequently for fire extinguishers, life preservers, and running lights. Each boat

must be registered with the federal manager of the dam,

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

and the permit issued must be on board at all times the

boat is in use on the reservoir.

and the permit issued must be on board at all times the

boat is in use on the reservoir.

The area is festooned with many historical sites. At one point of the lake historians claim Lewis and Clark bartered with the Indians for food. Ancient covered wagon tracks, barely discernible, can still be found in this area. The old ruts of stage coaches that ran from Yankton to Montana are still visible. Other attractions include the Devil's Nest wilderness country along the lake, the Bon Homme Mennonite Colony, the trip across the mighty Missouri on Running Water Ferry, a scenic ride along old Bazille Creek, the government mill site of frontier days, the Santee Indian Mission opposite Springfield, and the historical marker at Bazille Creek that recalls the ancient legend of "Maiden's Leap."

Future plans call for the complete development of eight additional recreation sites. The Bloomfield area is partially developed with tree plantings, picnic tables furnished by the Bloomfield Lions Club, fireplaces, water and a partly completed boat ramp already in partial use.

The following areas are totally undeveloped but will be in the near future: Bon Homme, road to this area will be built in the spring; Devil's Nest is an ideal wilderness area, with trails leading to this site only; Area No. 8 has no name at present; Knox, is a completely natural area which is suitable for camping in the rough, fishing and hunting; Santee, the heart of the finest duck hunting country; Lost Creek and Deep Water areas are ideal for fishing, picnicking and camping.

For the waterfowler, Gavins Point offers unsurpassed shooting opportunities. On the day Carl and I visited this area, thousands of mallards were trading in and out of the near-by cornfields. Sportsmen who would like to do some jump shooting, stalking among the trees in the flooded bottoms, pass shooting, or calling the ducks into their decoy spreads, will find this area hard to beat. Deer can be seen in the heavily wooded ravines. And upland game birds abound in the rugged areas, much of which is practically unchanged since pioneer days.

Gavins Point Dam Reservoir, was built by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. M. O. Steen, Nebraska Game Commission director, is chairman of the Inner-Agency Council, the group is charged with area's management. Council members include representatives of the South Dakota and Nebraska Game Commissions, U. S. Fish and Wildlife, National Park Service and Corps of Engineers. All are striving together to develop an area which in time might well become one of the country's finest recreation sites.

No more rustic nor beautiful camping grounds can be found anywhere than right around Lewis and Clark lake. Here you will find lush vegatation growing in reckless profusion, rushing creeks, rugged bluffs, all as nature made them thousands of years ago. Near-by towns offer fine hotel and motel accommodations for visitors who chose not to camp out. And during the summer, modern cabins are available at not-too-distant Niobrara State Park.

THE ENDCLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS

Rales for classified advertising: 10 cents a word: minimum order $2.50 TAXIDERMY Mounting fox, raccoon, or badger rug, $10, coyote or bobcat, $15. Strange, Nebraska City, Nebraska. ICE FISHING ICE Fishermen! Free Catalog of hard-to-get Ice Fishing Bobbers, Ice Rods, Jigs, Spoons, etc. Dept. 4, Dickey Tackle Co., South Bend 28, Ind. Hybrid worms for ice fishing—tough, lively. Fishing instructions if wanted. Large, medium, SI.35 a hundred. Phil's Bail Supply, Ericson, Nebraska.PHOTO NEWS

HOW DOES A FISH SWIM?

HOW does a fish swim? Just by swimming—some may be tempted to retort, but it is not so simple as that. There are three ways of swimming, not all readily obvious to the eye. Indeed, in its own strange, dense, heavy medium the fish is a continual miracle of locomotion.

The three distinct swimming methods are first and foremost by muscular movements of the entire body, by fin and tail movements, and by jet- propulsion of streams of water from the gills. Most fish use all three methods, sometimes together, sometimes singly.

It is generally assumed that a fish swims by moving its fins, but in actual fact a fish's principal motive force lies in its elaborately muscular body walls. The fins play a very secondary role in forward motion in almost all kinds of fish. Every fish has a great body mass of marvelously interconnected W-shaped muscle segments reaching from gills to tail. These segments are the main portion of the fish we eat, and without their very specialized design no fish could glide through the water as it does.

This muscular construction enables the fish to move forward in sinuous fashion by driving the resistant water backward from the body surface. The easy, co-ordinated body strokes produce waves of pushed-back water. As these pass along the body alternately on each side, successive parts of the creature's body are pressed against the water, and so sufficient forward forces are produced to drive the fish along, even against currents. This successive contraction of the muscular segments with its alternate pushing against the water first on one side and then on the other may be compared to the way a skater pushes against the ice with alternate legs. The faster the fish moves, the more violent this muscular action has to be, as is immediately obvious to anyone watching any fish endeavouring to make a swift get away. And the narrower and slimmer the fish, the greater the size of the muscular contractions, which are largest in the eels and lampreys.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note that this side-to-side method of progression is the exact reverse of the swimming technique of aquatic animals, like porpoises, seals, and whales. With a totally different body structure, and the need for continual replenishments of air, they have found it easiest to swim by a vertical up-and-down style.

It is this completely concentrated muscular constructtion that gives the fish its mastery of the water. No land creature has its main motive force compacted entirely into the body wall. Instead, the forces are dissipated into limbs—arms, legs, wings, each with their own operative set of muscles. The fish is really a single complex unit whose every movement is controlled by the successive interplay of its linked muscles stretching from head to tail.

Nevertheless, it is easy to exaggerate the fish's performance in its chosen habitat. To ourselves, living continously under the law of gravity, water seems so dense and heavily resistant to our physical movements that we tend to assume that fish really achieve something superhuman when they reach speeds of 20 or 30 miles per hour in it.

18 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

What we may forget is that, compared with our own motive efforts, the fish can achieve much greater economy of energy. The water in which he lives has a specific gravity almost equal to that of his own body. This of course means that most of his weight is held up by the water, and hardly any effort on his part is needed to support himself. By way of example, a 20-pound fish in salt water weighs only about one pound, so when he swims along or rises, he has only to lift one-twentieth of his actual weight. In this way he can conserve almost all his energy for swimming forward. It is as if a man of average weight found himself on land weighing only seven to eight pounds. How agile and mobile he, too, could be!

This also explains why we can catch a 20-pound salmon on a line with only a 5-pound breaking strain providing we gaff him. A plaved fish allowed to tire himself on a run line actually does so almost entirely by moving forward, not by dragging the strain.

Fin and tail movements play a comparatively minor role in swimming. For a long time it was thought that both were of paramount importance to fish motion and balance, but much of this theory has been exploded by experiment. Fins and tail aid forward progression and play a small part in maintaining balance, but their chief use is in general maneuvering and steering, in the countless delicate movements—a flick here, a glide there—that keep a fish on the course he wants. They help him to dive or rise in the water, and the fins especially enable him to remain motionless in one spot whenever necessary. As the normal breathing out backward of water from the gills tends to move the fish forward, the sinuous back-paddling of the fins counteracts this and keep the creature immobile.

But the importance of fins is much smaller than might be expected. Experiments in which the caudal fins of certain tank fish were trimmed off with scissors showed that they could swim as well and as fast as unmutilated fish of identical size and kind. Removal of the dorsal and anal fins affected balance a little at first, but this was soon got used to. Total removal of the fins did not prevent the fish from swimming normally, though it reduced maneuverability, for many fish find the pectoral and ventral fins useful for sudden braking in the water. For this reason, fish with small or stiff pectorals tend to swerve aside from obstacles rather than stop suddenly before reaching them. Black and striped bass, on the other hand, with their high flexible ventrals and pectorals can brake swiftly and even swim round in a flash as if on a pivot.

The third method of swimming, by simple jet-propulsion, is used all the time by a fish swimming normally forward, and as we have seen has to be counteracted when the fish wants to remain stationary. It is possible that it is also used especially to aid a sudden getaway when the fish has to dart off at speed from scratch. But its chief use is confined to flatfish which spend much time more or less motionless on the bottom, living on one side. Most flatfish seem instinctively to realize that if they breathed with the upper, exposed gill, its opening and closing would betray their presence to enemies, for the avoidance of which nature provides natural camouflage. So instead the body is slightly arched and breathing is carried on by the lower, hidden gill, which sends its stream of water along under the back and out by the tail. When a flatfish wants to move off in a hurry, it simply sends a powerful stream of water out through this selfsame gill, which lifts it right off the bottom and well away to a good start. Jet propulsion of this kind enables all flatfish to become instantly mobile if necessary.

There is also a theory that by closing one gill chamber and sending a strong jet of water out of the other may also enable heavy fish to turn easily, but of all the three swimming methods this one has received the least attention, and much of our knowledge of it is speculative. But it is clear that the gills are primarily breathing organs, not swimming devices. A fish's best swimming device is its own marvelously designed body.

THE ENDAre You Changing Your Address?

If so, please complete the following form and send to OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, State Capitol, Lincoln 9, so that you will continue to receive your copies of the magazine. Allow six weeks for processing. Name....... Old Address ......... City ....... State ....... Please look on the mailing label of your magazine, find the number which appears on the right hand side, and copy it here: .......... New address ..... City ...... State ....... JANUARY, 1959 19

THE SHOT THAT KILLS TOMORROW

Just one tiny lead pellet picked up while feeding can be as deadly to duck as one lodged in the head by Gene Hornbeck Photographer-Writer Illinois Natural History Survey PhotosFEW hunters realize just how many ducks fell to their guns during the recent hunting season. We know how many birds graced our table, but are inclined to forget the incalculable number put down and never retrieved. And this number continues to mount for the loss of waterfowl to hunters' guns does not end when the last cripple is taken by a predator or dies from gun shot wounds.

Long after the last gun has sounded over our marshes and lakes, ducks will continue to die—and as a result of hunting. Time is of no essence. A shot fired the last day of the season can kill a duck today, tomorrow, or even next summer or fall. Game men and biologists call this malady lead poisoning. It isn't the immediate type, such as you deliver with a well-placed shot on an incoming mallard, but a prolonged sickness caused from lead pellets picked up in feeding. One tiny pellet lodged in the gizzard can be just as deadly as one placed in the head. The only difference is that it takes longer to kill. Lead poisoning in waterfowl is nothing new, with records showing it occurring as early as 1874. And it is taking an ever-increasing toll of waterfowl.

Before going further, I would like to add that man will suffer no ill effects if he consumes a bird afflicted with the poisoning.

Occurrences of the malady are affected by gunning pressure, water levels, and duck concentrations. Combinations of pressure and low water levels in a concentrated feeding area bring about outbreaks of lead poisoning.

Such poisoning occurs most frequently in redheads, canvasbacks, ringnecks, pintails, and mallards, in that order. This is based on studies of the different species and the occurrence of shot in each. Biologists attribute the greater incidence of shot in some species to a difference in feeding habits. Mallards and pintails will feed off the bottom, sometimes puddling into six inches or more of silt in search of food. Although they dive rather than puddle, the same is true of the canvasback and redhead. Species such as the gadwall and baldpate are not as were induced into gizzards of these ducks in tests apt to pick up the shot because they feed on leafy plants rather than on seeds and other organic matter on the bottom. Shovelers and green-winged teal skim the surface in feeding and are less frequently victims of the lethal lead pellets. Blue-winged teal, on the other hand, have a higher percentage of shot because they puddle or feed more off the bottom.

Lead poisoning is more prevalent in waterfowl using heavily gunned, shallow ponds and lakes. Some of such areas have been used for decades and the accumulated amount of lead on bottom is tremendous. The pellets are insoluble and can remain for years within easy reach of waterfowl.

In some of the heavily gunned eastern states and

along the southern coastal marshes where there is a

heavy wintering concentration of waterfowl, as high as

10 percent of live-trapped birds were found to have

shot. When applying this percentage to a heavy concentration say 50,000 birds, one can visualize the large toll

claimed by poisoning. All lead poisoning is not necessarily

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

fatal, its seriousness depending on the number of shot

ingested into the gizzard, quantity and quality of food

intake, and physical condition of the bird.

fatal, its seriousness depending on the number of shot

ingested into the gizzard, quantity and quality of food

intake, and physical condition of the bird.

Through experiments conducted by James Jordon and Frank Bellrose, of the Illinois Natural History Survey division, some pertinent facts were disclosed. In one study, they banded and induced one pellet into the gizzard of 391 trapped wild mallards and two pellets into 392 birds. These ducks, along with 389 undosed banded birds were released just prior to hunting season.

Band returns from hunters showed that the birds with two shot were much more susceptible to the gun than the other two groups. The same held true of the birds dosed with one shot in relation to the undosed birds. Mobility of the birds was retarded as the poisoning began taking hold. In the undosed birds, data shows that they moved on the average of seven miles from their release point. One pellet shortened this distance to six miles, and two pellets cut it down to four miles.

Jordon and Bellrose concluded that birds ingesting shot during or before the season become lethargic and in turn become much more vulnerable to the gun.

It is the general behef of these researchers that 60 to 80 per cent of the birds carrying one shot will die as a result of the pellet, if they depend on a diet of seeds. Their research shows that a leafy diet, such as coontail, duckweed, pondweed, and other aquatic greenery, will bring about a much higher recovery from lead poisoning. The majority of grain and seed-fed birds died, with a few making a prolonged recovery.

Heavy losses of waterfowl in a certain area occur occasionally, and the loss can be traced to a combination of the factors described. Such an area is Capitol Beach Lake near Lincoln, where losses occur off and on. George Schildman, District V game supervisor for the Nebraska G^me Commission who has studied the problem, lists the following factors as effecting the size of the loss at Capitol Beach.

First, the area is heavily gunned, so shot is readily available to the feeding birds. Second, Capitol Beach supports a heavy population of migrating birds in the spring.

This lake is one of the few that has offered any data on the effects of lead poisoning on geese. About 3,000 snows and blues used the area for a period of a month. During the four-year study of mortality from lead poisoning, the highest loss was recorded in low water years and the least in high water or no water. In the dead geese examined, the number of shot ranged from none to a phenomenal 78 in one gizzard.

This study, as others indicate that death from poisoning usually occurs within a month after ingestion.

Lowest loss at Capitol Beach was 17 geese in 1952, with a high of 320 in 1953. It can be added that in the mid 50's birds did not use the area because of the lack of water.

Control over the losses from lead poisoning is very limited presently. Some work has been done with a substitute for the lead. Only iron pellets have shown no ill effects when fed to birds but evidently the manufacturing cost and perhaps the ballistics of the iron shot prohibit its production.

In some wintering areas, where possible, biologists keep the birds out of danger areas by firing guns, hazing with a plane, and using the scaring devices. Flooding or draining these areas, if feasible, can alleviate the problem.

Sportsmen, too, can be of some help by exercising more control over their shooting, especially at birds that are out of range. This practice not only cripples birds but also deposits a lot of unnecessary shot in the area.

Symptoms of the affliction are fairly easy to recognize. The bird becomes weak and shows a high loss of body weight. The passage of bright-green droppings is commonly observed within two days after ingestion of the pellet. In many cases the vent becomes stained.

During the second and third weeks of illness, the birds become droopy; their whole appearance is one of reduced alertness and vigor. During the third and fourth weeks, flight becomes impossible. Birds in the advanced stages of the illness seek isolation and seldom recover.

Efforts to control lead poisoning are continuing, and in time someone will come up with the right answer.

THE ENDBobcat Storms At Hunter

IN Holt County recently, a large female bobcat created a stir of excitement, according to Harry A. Spall, local conservation officer. The animal, after a show of belligerence, was killed by Jim Boies of Ewing near Willow Swamp, five miles west of town.

The front paws of the bobcat measured 9 1/2 inches in circumference; the claws were 1% inches long, and the fang teeth were one inch long. The animal weighed 23 pounds, and the outer hair was almost white with very few spots showing through.

"As I was walking along, I heard what seemed to be a cat hissing at me," Boies told Spall. "When I saw the noisemaker, I was startled as it was less than 10 feet away and big. Her back was arched and the hair standing straight up. I backed away, climbed a bank, looked again, and she was still standing her ground."

By the time Boies returned from his car with a .22, the bobcat had disappeared. Boies trailed the animal approximately two miles in the snow, circling back to its den which was within half a mile of the original contact.

The bobcat stormed out of the hole, straight at Boies. His first shot caught it just above the eye, the bullet entering the brain for a clean kill.

It was later discovered that a duck hunter had filled the cat with shot earlier in the week. This possibly could have been the reason the bobcat was on the prod.

STATE TRAPPER

THE outdoor social register, which includes 25 million persons from all walks of life, does not have a large volume of trappers. For one thing, trapping is a sport for the hardy, and it takes know-how to go after animals of the wild.

Another thing that has cut into the trapping ranks is the price of fur. At one time a person could realize a good income from a winter's work, but with the price of fur low, many persons in recent years have quit the game. Still others, though, continue to run their lines as a hobby or sport and to supplement their income.

For those persons interested in trapping, Nebraska offers a large variety of fur-bearing animals, including badger, beaver, civet, fox, mink, muskrat, opossum, raccoon, skunk, and other. Beaver, muskrat, and mink are the most popular animals. The annual state furharvest inventory shows that muskrats furnished most of the action during the 1957-58 season, with trappers taking a calculated harvest of 112,538 animals. Mink brought the most money, selling for $11.55 last year; the calculated take was 10,239. Beaver was priced at $5.59, and the calculated harvest in the state was 7,717.

Harold Miner of Wakefield probably spends more time at trapping than any one individual in the state. Trapping is his full-time job. He is the state trapper, and he is busy the year around matching wits and skill with animals of the wild.

The Wakefield trapper receives letters, and sometimes emergency calls, from state officials asking for

his help when wild animals are doing damage on any

state owned lands. Miner packs the needed equipment

and is off to any and all parts of the state to ply his

trade at a moment's notice. Usually it is beavers which

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

are raising havoc, such as destroying valuable timber.

Muskrat, too, though, get out of hand and from time to

time have to be thinned out in the state recreation

grounds.

are raising havoc, such as destroying valuable timber.

Muskrat, too, though, get out of hand and from time to

time have to be thinned out in the state recreation

grounds.

Miner has been with the Nebraska Game Commission for 16 years, working first, though, as a warden. His assignments have included all types of predator control, but at present he devotes all his time to trapping on stateowned areas. Years back, he spent considerable time hunting coyotes from an airplane, and his air mark of nine coyotes in 20 minutes probably stands as some kind of an individual record.

People interested in trapping and who look on it as a romantic occupation have much to learn. For trapping means being out in all kinds of weather, walking endless miles to check trap lines, and spending long, tedious hours skinning and stretching pelts. It all boils down to one thing—a good hard job.

Miner's day usually starts in early morning, for he likes to be working his trap line by daylight. He has to run the line, take out the catch, reset the traps, and then skin the fur bearers. Once a line of traps are set out, they must be run every day. Miner prefers to run his muskrat traps twice a day and the beaver sets once. A beaver is nocturnal and seldom leaves his lodge in the daytime.

The traps must be run at least once a day, Miner said, because muskrat and beaver have soft feet. If given enough time, these fur beavers, taken in a live set, will release themselves from the trap. A captured animal will work, if given enough room, in a circle, wringing off its foot. In some cases, a muskrat or beaver will even gnaw off a foot to escape.

"Have traps, will travel" is calling card of this wildlife troubleshooterMost trappers, though, including Miner, prefer a drowning set which insures a catch and less suffering for the trapped animal.

Most of the traps put out by Miner are blind sets, so placed to outsmart the animal. These are placed along trails, in runs, and at the bottom of slides which the animals use going to and from dens. The traps must be set so that the animals cannot see them and will walk into the spring jaws.

Of course, Miner points out, all trapping is a matter of improvising as you go along. Conditions will be different on every lake or stream; no two places are alike. One has to work big and small streams, lakes and rivers, shallow and deep waters. The trapper has to figure out what kind of set will be the best bet to take the desired animals.

Trapping muskrat, Mener said, is an easy task as the rodent will walk or blunder into any trap set in or near the lodge, slides, and feeding stations. A stop-loss trap, designed to prevent escapes, is preferred by Miner in trapping muskrats. When the trap springs, a wire guard device moves high up on the body of the animal, holding it in such a way that it can neither twist or gnaw off.

Miner last year took 500 muskrats on state-owned property. Several years ago, he trapped approximately 2,000 "rats" on Ballards Marsh in Cherry County.

Muskrats live from day to day, never storing up

food. They must leave their hut each day for food,

making it easy to trap them. Depending on the season,

they like to lunch on tender grass stems, goldenrod,

JANUARY, 1959

23

smartweed, ragweed, cockleburs, barks and leaves of tree

seedlings, and any type of aquatic plant life. Muskrats

must live in water which never freezes tight, as they

subsist on vegetation they dig off the bottom of lakes

in the winter. If a lake or stream freezes to the bottom,

the muskrats will perish.

smartweed, ragweed, cockleburs, barks and leaves of tree

seedlings, and any type of aquatic plant life. Muskrats

must live in water which never freezes tight, as they

subsist on vegetation they dig off the bottom of lakes

in the winter. If a lake or stream freezes to the bottom,

the muskrats will perish.

In the winter months, Miner tries to trap most muskrats in plunge holes. Inside the house is a platform or table where the muskrats feed. Leading from the table are three or four plunge holes, where the rat goes into the water to leave the house. Miner sets his traps just under the water in the plunge holes.

The beaver is tougher to capture than muskrats. As little disturbance as possible in the area of a beaver colony is advisable, for beaver are easily spooked and become very wary. Once one has been spooked, the trapper may as well move his sets to a new location. As a rule, beaver won't come near anything that carries the odor of man.

Best sets for a beaver are those in den entrances, landing places, and slides, wherever they cache food for the winter. The beaver is an industrious fellow, storing piles and piles of timber in the water for his winter food supply. This flat-tailed rodent is a vegetarian and has a varied menu. In the summer he will eat aquatic plants, grass, herbs, roots, shoots, buds, and leaves of small land plants and shrubs. In winter he lives off the tender bark of trees.

The beaver works hard to get a good stock of food in the water. In winter he swims under water to his larder, selects a choice morsel, and returns to the lodge for an appetizing meal of bark. When the limb is stripped of bark, it is tossed to the bottom of the pond. The beaver will then pick up more food and take to the lodge. This discarded wood does not go to waste, for it is used in the spring for building dams. Seldom is fresh wood used for building purposes.

Because a beaver is busy stock-piling food in the fall, Miner has found bait traps the best at that time of year. Trap sizes No. 3 or 4 are recommended. In the fall, intent on storing food, the beaver spends considerable time going out on land for wood to haul for his winter cache. So sets at the bottom of the slide bring excellent results.

These are placed at the bottom of a slide, with a tender cottonwood or willow branch set between the trap and the slide. This branch acts as the bait. All such sets are made under water; the traps are staked toward deeper water, so they are a drowning set. Such a set is made with a smooth wire about the size of ordinary telephone line. It is fastened near the top end of a heavy stake which is driven into the stream bottom near the trap. The wire extends three or four feet out into deeper water and is held by another stake or large rock. A lock is placed on the running wire by tightly winding another piece of wire about it, allowing a free end to extend about six inches at an angle to the running wire. The free end of the lock has to extend toward the deep water stake. The running wire runs through a ring of the trap chain.

When the trap springs, Miner said, it is the natural tendency of the beaver to fight the trap toward deep water. When the chain ring is pulled over the lock, the beaver is trapped in deep water and drowns.

In winter with lakes and streams iced over, bait is still the best bet, in Miner's opinion. Cottonwood, willows, or a bundle of bark serve as bait. In shallow water, the bait is placed just under the ice and the trap is placed on the ground below. Bait is shoved to the bottom in deep water and then ringed with traps.

As in the case of most life on earth, the beaver's thoughts turn to romance in spring. So scent traps set in water or on the bank are used at that time. Beavers of both sexes have a pair of musk glands which are located in the rear of the abdomen. These glands or "castors" from dead beavers are used to scent the traps. The musky liquid was once believed to have medicinal values, and the castors were sold for $10 to $20 per pound. They no longer have any commercial worth.

Any exposed bait or trap should be free of human odor if the trapper is to meet with success, Miner emphasized. He wears glovers while setting out traps. And after the traps are set, he splashes all bait wood and stakes with water.

Skinning a muskrat is easy work, Miner commented, but skinning a beaver is a different story. The beaver has muscles attached to the skin, so it has to be cut out all the way; it will not slip out of its skin like a muskrat or rabbit. Miner's set method is to cut off the legs approximately halfway up and then slit the underside of the creature from the tail to the teeth. Then, inch by inch, the skin has to be cut away from the muscles. Beaver skin come out perfectly round and are stretched over pelt boards.

As state trapper Miner said earlier, no two days are alike on a trap line. Each day brings new experiences. For one man who loves the outdoors, trapping is a fine sport.