OUTDOOR NEBRASKA WINTER ISSUE

1955 15c

Outdoor NEBRASKA

Vol. 33. No. 1 EDITOR: Wallace Green Artist C. G. Pritchard Circulation Marjorie French Leota Ostermeier COMMISSIONERS Donald F. Robertson, North Platte; Harold H. Hummel, Fairbury; Frank Button, Ogallala; Bennett Davis, Omaha; La Verne Jacobsen, St. Paul; Floyd Stone. Alliance; Leon Sprague. Red Cloud. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: Paul T. Gilbert. CONSTRUCTION AND ENGINEERING DIVISION: Eugene H. Baker, supervisor. FISHERIES DIVISION: Glen R. Foster, supervisor. GAME DIVISION: Lloyd P. Vance, supervisor. INFORMATION DIVISION: Wallace Green. LAND MANAGEMENT DIVISION: Jack D. Strain, supervisor. LAW ENFORCEMENT DIVISION: William R. Cunningham, supervisor. LEGAL COUNSEL: Carl H. Peterson. HOW TO SUBSCRIBE OUTDOOR NEBRASKA is published quarterly at Lincoln, Nebraska, by the Game, Forsstation and Parks Commission. Subscription rates are $1.00 for two years and $2.00 for five years. Single copies are 15 cents each. Remittances must be made in cash, check or money order. Send subscriptions to OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, Department C, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska. CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please notify this department immediately of any change of address to assure prompt delivery of the next issue to the new address.All material appearing in this magazine may be reprinted upon request.

NEBRASKA FARMER PRINTING CO.. LINCOLN. NEBR.Editorial

Occasionally we run across youngsters with a sound sportsman philosophy in hunting, fishing and conservation. We have often wondered at these rare and happy incidents—Did they get their ideas from books, magazines, teachers, relatives or youth organizations? It is even more rare when we can put our finger on the source of influence that has developed a truly "Future Good Sportsman?

We submit the following open letter to farmers and sportsmen from a 10-year-old SPORTSMAN, in order to let you share one of these experiences with us.

To Farmers and Sportsmen:I am too little to go hunting. I go fishing a lot. I know something about hunting and wildlife and farmers from my older brothers and my grandfather and from our bird dogs.

The farmers own all the land and they make a living from raising crops of grain and livestock. The game birds and animals and fish belong to all the people in Nebraska. They are controlled by the farmers, however, as they use his land to make their living. They are owned no more, no less, by the farmers than by my teacher at school, the banker, my mother or grandma, nor by the hunters or fishermen. Wildlife is owned by all the people, with the State Game Commission setting the season when it can be harvested.

In order for the hunter or fisherman to get any game or fish he has to, most often, go on the farmers' land to find it. It is better to hunt or fish where you know the farmer. I don't know very many farmers, so I have to ask strangers to hunt on their land or fish on their ponds or creeks. It is best to first go up to the farmer and tell him your name and where you live. Then ask him if you can hunt or fish. If he says "Yes,' from then on you are his guest. Don't destroy any of his things at all, his crops, his fences, his farm implements or any buildings. Don't cut down his trees. Don't shoot near his house or his animals and don't let your dogs get close to his cows or chickens.

Even if the dogs would not hurt anything, they might scare them and so do damage.

All of these things belong to the farmer and he uses them to make a living for himself, his wife and boys and girls. Be careful of them. When you are ready to leave, go and thank him and tell him what a good time you had. He might ask you to come again and that is what you want him to do.

If my brothers and my grandpa and other hunters and fishermen do this, maybe I can go hunting too, when I get big enough.

Ronnie Kluge, Age 10 THE COVER: This issue's cover depicts a flock of mallard ducks on a typical wintering area "some place on the Platte River' according to Staff Artist C. G. "Bud" Pritchard. See pages 14 and 15 for more information on the mallard in Nebraska.

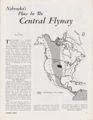

Nebraska's Place In The Central Flyway

by Harvey MillerTHE CLOSING of a waterfowl hunting season generally means open season on fireside discussing; or sometimes just cussing the duck shooting. Nebraska, now that the 1954 season has passed, is no exception, but is instead a rather outstanding example. And always, the loudest discussing and cussing concerns the weather or the flyways. Admittedly, no one can do anything about the weather but cuss it, but what about the flyways? What are they? What do they do? Are they good for Nebraska hunting or is Nebraska in the wrong flyway?

It was discovered, as a result of the earliest waterfowl banding, that each species of waterfowl has from one to several migration pathways from the breeding grounds to the wintering grounds. Each of these migration routes is used by a certain segment of the population of a waterfowl species and is relatively constant year after year.

Four Main RoutesWhen these migration routes are mapped for all the species of waterfowl passing through the United States, it is apparent that there are four major groups of routes with little overlapping from one to another, especially from latitude 45° to the Gulf Coast and Mexico. One group goes through the Atlantic Coastal region; another the Mississippi Valley; another the Missouri Valley and the Prairie Pothole region; and the last follows the Pacific Coastal region.

Central FLYWAY

The Fish and Wildlife Service, a branch of the U. S. Department of the Interior, charged with the enforcement of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and all the laws under this Act, recognized these major groups of migration routes as possible management units. It then established the flyway management system consisting of four separate administrative flyways, the boundaries of which arbitrarily conform to state lines and which approximate as nearly as possible the regions through which the

(Continued on Page 4) WINTER ISSUE

major groups of species migration routes pass. Thus was formed the Atlantic Flyway, the Mississippi Flyway, the Central Flyway, and the Pacific Flyway.

Blue Wing Teal

As the major portion of ducks passing through Nebraska follow routes across the Missouri River and Prairie region, this state is included in the Central Flyway. The other states included are Montana, North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico.

Flyway CouncilIn 1948, these states formed the Central Flyway Waterfowl Council with membership composed of the directors of the respective game departments in this flyway. The main purposes of this organization are to promote cooperation between the member states, to promote cooperation between the group and the Fish and Wildlife Service and to foster better waterfowl management within the Flyway.

The Fish and Wildfile Service, for its part of the cooperative effort, provides a Flyway Representative to act as its representative in all flyway problems.

In an advisor capacity under the Council, the Central Flyway Waterfowl Technical Committee, made up of the waterfowl technicians of the member states, does some of the research work necessary for better management. It goes without saying that sound management must be based on facts and that probably the most important fact is population information.

Collecting the FactsThe first population count of the year is that made on the wintering grounds. Here, simultaneously throughout the Flyway, trained observers working on foot, in boats, cars and airplanes count the ducks in their areas. This count, as with all others made in waterfowl work, gives only an index to the actual number of ducks and geese present since it would be humanly impossible to count each and every individual bird. This winter index is the most accurate as the birds are concentrated and the cover is light. It is vitally important as it gives the first indication of the number of each species to survive the hunting season.

After the ducks have returned to the nesting grounds in the spring, a count is made to secure the species composition and an index to the size of the breeding population. This count is again made simultaneously throughout the Flyway and also on the Canadian breeding grounds by both Canadian Conservation agency and Fish and Wildlife Service personnel. This index provides the first real clue as to the number of birds that can be expected to come south through the Flyway the next fall.

ProductionNext, production success is measured. This is done over all the nesting grounds by personnel literally living with the birds in an effort to get a more acurate idea of the size of the fall migration. This is the most difficult fact-finding job of all as the ducks are scattered in the most remote areas, they and their broods are the wariest and the cover is the heaviest. But, it is especially important as poor success in a very large breeding population would mean a small migration or conversely, good success in even a small breeding population could still provide an excellent hunting season.

Next, the fall migration itself is studied in an attempt to secure an average arrival time for each species in any one area. Knowing this enables the administrators to select hunting seasons to the best advantage both for harvesting the plentiful species and protecting those low in numbers.

During the waterfowl season and immediately after, hunters are contacted to determine their hunting success. This, when compared to the size of the fall migration, shows the effect of the regulations on the total harvest. It also shows, to some extent, how the harvest affects the population as a whole.

Pintails

The last job on the yearly agenda in waterfowl research is banding. As banding and the recovery of the banded bird, whether it is shot by a hunter, found dead or trapped at some other banding station, is the only way of tracing an individual duck's migration route. This amounts to the most important job in finding the facts necessary for basic flyway management techniques. In addition to showing the migration route, bands also give information relative to the ducks' longevity, time patterns in migration, the hunting pressure that species sustain and even a key to the total duck population.

Co-op MeetingJust prior to the time that the waterfowl seasons must be determined and as late as possible into the brood-rearing season, usually late July, the Central Flyway Waterfowl Technical Committee meets with Fish and Wildlife Service technicians, who have worked on the Canadian breeding grounds, the Central Flyway Representative and other interested persons.

At this meeting, findings from each of the research jobs in all the states and in Canada are presented. Very careful consideration is given each phase of the information and finally a fall flight forecast is made. On the basis of this forecast and the limited knowledge available as to how the hunting seasons affect the populations, suggestions as to the opening date, length of season, shooting hours and bag limits are drawn up.

RecommendationsImmediately after this session the Committee meets with the Central Flyway Waterfowl Council. Here, the Committee presents a summary of its findings, its fall flight forecast and hunting season suggestions. The Council then decides, through majority vote, its official recommendations to the Fish and Wildlife Service on not only hunting season regulations, but on other management problems as well.

The Council then selects two members, customarily the Chairman and the past Chairman to represent the Flyway and to present its recommendaitons at the National Waterfowl Advisory Board meeting held in Washington.

Final DecisionThe Advisory Board is made up of

representatives from each of the four

Flyways, the Fish and Wildlife Service,

4 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Ducks Unlimited, the Wildlife Management Institute and other such

groups. At this meeting, held about

August 1, the recommendations of each

of the groups are presented and the

final regulations, as they will affect

each Flyway, are then drawn up by

the Fish and Wildlife Service and presented to their Director for his approval.

Ducks Unlimited, the Wildlife Management Institute and other such

groups. At this meeting, held about

August 1, the recommendations of each

of the groups are presented and the

final regulations, as they will affect

each Flyway, are then drawn up by

the Fish and Wildlife Service and presented to their Director for his approval.

These meetings must be held on these early dates as it requires nearly four weeks to have them printed and by Federal Law, the regulations must be published thirty days prior to their taking effect, and of course, the first hunting season starts October 1.

Thus it may be seen that although the Fish and Wildlife Service is responsible by law for the final determination of the hunting season regulations, the Central Flyway Waterfowl Council does protect the States' interest. The Service establishes a period during which the hunting season in the states may occur and then allows each state the perogative of selecting its own opening date.

As with the other Flyway States, the Nebraska Game Commission has as its only official authority in the determination of this opening date with all other regulations being determined by the Federal Government.

Nebraska has attained increased importance in the Council Organization with the election of the Game Commission Executive Secretary, Paul T. Gilbert, as Cenetral Flyway Waterfowl Council Vice-Chairman. Mr. Gilbert will automatically be elected Chairman of the Council October 1, 1955, and as such will represent the Central Flyway States at the Advisory Board Meeting in Washington in late July, 1956. As Past-Chairman, he will again represent the Council at this meeting in 1957.

Importance of SystemThe most important gain of the flyway management system is a hunting season adjusted to harvest a maximum number of waterfowl and yet insure an adequate breeding population for the next year. For example, the Central Flyway has more ducks passing through it and less hunters than has the neighboring Mississippi Flyway. Therefore, for the past several years, the Central Flyway regulations have allowed five extra hunting days and one more duck in the daily bag. The Pacific Flyway in turn, has been allowed a daily bag of four ducks over the Central Flyway, provided however, that at least three of those ducks be pintails or widgeons; due to serious crop depredation by these ducks. This is also an example of how the various species may be managed on a flyway basis.

Of course, the problems of flyway management are many.

Ten major species of ducks and at least ten others of lesser importance migrate through the Central Flyway, each species in some way is different from the next. In addition, four major species of geese, including one having four common sub-species, occur along with dozens of other waterfowl and shorebirds that are, have been, or could become game birds.

Changing PatternThe migrations of all these are affected by the rainfall and weather conditions. A good example is the 1954 season just passed; when late fall rains and unseasonably mild weather held the birds north. Then, when they did move south, continued mild weather allowed a very leisurely migration. An extremely large number of ducks moved through the state in small groups numbered by the dozens, but because there was no "flight" of thousands, Nebraska nimrods were disappointed to say the least.

And quite often, for no apparent reason at all, ducks simply fly in a different manner than they are supposed to. Nebraska reared blue-winged teal banded in the sandhills were recovered in Minnesota in 1952 and 1953 but seem to have by-passed that state entirely in 1954.

Some Over-lapAs the vast majority of ducks passing through Nebraska are Central Flyway birds, the state is rightly placed within that Flyway. It is true that some Mississippi Flyway birds migrate along the Missouri River and even through the eastern one-third of the state but these birds probably represent the small minority of the overall population.

Of course, in a state as large as Nebraska and with its differences in altitude and great variations in types of habitat available from one area to another, there is bound to be a difference in the arrival time and length of stay for any of the species that may occur. The sandhills with shallow lakes and marshes are attractive to different species of ducks than are the reservoirs surrounded by grain fields. Also, these shallow areas usually freeze over early thus precluding the possibility of ducks staying late into the fall. The final freeze leaves only the hardy mallards in areas where warm water seeps in or drainage ditches provide the needed open water.

Canada Geese

Probably the only way of equalizing the hunting opportunity for each section of the state lies in zoning. Under the zoning plan, different sections of Nebraska could be opened at different times so as to include the peak waterfowl populations of each area in the hunting season. Of course, it must be stressed that; the same flock of ducks tend to use one particular area year after year making the possibility of overshooting the flock an ever-present danger.

Need More FactsFor this reason, zoning probably will not be attempted until further research can show how the hunting pressure actually affects the duck population. Nebraska sportsmen are presently doing an excellent job of equalizing the hunting opportunities by accepting an early opening one year and a late opening the next.

The entire picture of waterfowl management becomes one of cooperation; cooperation in an all out effort to allow the greatest amount of duck and goose shooting and still faithfully protect the breeding population in order to insure duck shooting again, year after year. Waterfowl management techniques are slow in coming and difficult to understand but one may rest assured that such management will provide the most hunting for the most people most of the time.

Red Heads

Let's Take A Look At.... Winter Hill

by George SchildmanMANY descriptive and explanatory phrases have been expressed by some creative person, and they seemed to fit a situation, and eventually become a part of our everyday language. In the many bull sessions, in which last fall's hunts have been relived and the birds shot and reshot, the discussion often leads to the abundance or scarcity of birds and a comparison of recent populations with those of years gone by. One of the phrases quite frequently mentioned in these sessions is "winter killed."

The term is simple enough and seemingly self-explanatory. It also imparts to the listeners an impression that the speaker is at least somewhat well versed on the subject and the term is inclusive enough to explain extensive population losses.

However, the two words fail to explain to great extent when, where or why the losses occurred or how great they "are. Perhaps you are one of those who accepted the term outwardly but inwardly found it vague and lacking as a satisfactory explanation.

Early Winter LossesLosses are occurring continually in quail and pheasant populations as they do in most wild populations. The greatest number of birds in a given year occurs after the young are hatched. The population diminished from then until the young are produced the following year. Although losses occur throughout the winter period, there are periods when the losses are greater than others.

That first storm of the winter is likely to eliminate the least fit. Those individuals that are weak, diseased, crippled, or worn out from old age are likely to be eliminated at this time. However, the population as a whole enters the winter period well fed and in good condition. Food has been abundant and cover still exists in places where it won't be later, after the winter winds, snow and ice have flattened it.

Mid or Late Winter LossesLater on, in mid or late winter, when adverse weather is likely to be more prolonged, there may be another period of increased losses. These will probably include some birds we would prefer to keep for breeding stock. But there are birds that attempt to pass the winter in locations where food and cover do not offer them adequate security.

Except under exceptionally severe conditions, such as the 1949 blizzard, our winter losses of pheasant aren't very significant. Pheasants are a bird of our northern states and well adapted to winter life. With sufficient food and suitable cover in proper arrangement they do very well through the winter.

Cover ImportanceThe abundance of cover that existed during the summer and fall is severely diminished by late winter and numerous birds are forced to share crowded conditions of the relatively few locations that offer them security. Some birds try to exist under conditions that offer only marginal security and these are the birds we would like to save for breeding stock that are risking becoming victims of the winter elements. Some birds are lost because they selected ditches for roosting and became trapped under a snow-drift.

A more frequent cause of death is sleet storms which freezes over the nostrils and mouth resulting in suffocation.

Food AvailableLack of sufficient food is seldom a limiting factor for pheasants over most of Nebraska. However, pheasants relying on corn scattered on the ground in machine picked fields may have their food supply cut off by deep snow and ice. Normally, pheasants could survive a week or more without food, but as temperatures drop, a greater daily consumption of food is necessary to maintain their body heat. Thus, they may become victims of very low temperatures, if forced to go without food for several days, and particularly so, if the low temperatures are accompanied by strong winds.

Quail Hit HardThe winter period for the bob-white quail is a different story. It is a southern bird that does well in the states south and southeast of Nebraska. In fact it does well in the southern and southeastern parts of our state. Although he persists in isolated spots in all sections of the state, the severity of our winters keeps his numbers limited, dver most of Nebraska.

In our better quail range the winters are less severe and food and low growing brushy or woody cover growing in close proximity are more abundant, thus capable of carrying more birds through the winter.

Low TemperaturesAs is true of pheasants, severely low temperatures do not affect any appreciable losses as long as suitable food and cover are available. Unlike the pheasant, however, quail cannot withstand low temperatures if deprived of heat producing foods for very long. Body weight is rapidly lost if they don't eat daily and with the body weight goes their resistance to cold even though their roosting formation permits sharing of body heat.

The lethal effects of a winter storm and the effects of a daily supply of food can be demonstrated by the two feet of snow that covered most of southeastern Nebraska in March of 1948. The snow storm was followed by several nights of below zero temperatures. The bob-white population suffered losses during the period following the storm. Coveys that had their food supply buried beneath the snow perished.

The birds had lost as much as 30% of their body weight. Some had starved to death and others had lost weight and their resistance to cold nights; thus succumbing to the low temperature. Other coveys that still had good food available (hand-picked corn that had corn hanging on the stalk above the snow) passed the crisis with no appreciable losses.

General PictureBefore we conclude this article, and lest we leave you with the impression that Nebraska's annual losses of pheasants and quail to the elements of winter are of alarming magnitude, let's review the facts as we know them today.

Exceptionally severe winter storms (sleet and snow, high winds and low temperatures) is likely to be a lethal combination to important numbers of pheasants and quail. Winter temperatures are not a significant factor in pheasant mortality where adequate food and protective cover are available. Losses may be due to starvation, freezing, trapped beneath snow-drifts, and suffocation when ice covers their beaks and nostrils. Losses due to the elements of average winters in Nebraska are generally not too important over most of our pheasant range.

The type of food and cover combinations necessary to carry quail through our winters, is lacking over most of the state. Winter killed quail losses are not important in the southern and southeastern sections, except during the unusually severe winters.

6 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

NEBRASKA TRAPPING TIPS

MUSKRATOUR MOST IMPORTANT FURBEARER, INSOFAR AS NUMBER HARVESTED. AVERAGE ANNUAL HARVEST TOTALS ABOUT 250,000

SIGNNO. 1 1/2 STOP-LOSS TRAPS ARE PREFERRED

STOP-LOSS ATTACHMENT

Houses constructed Of AQUATIC VEGETATION

BANK DENS

FEEDING PLATFORMS CUT VEGETATION

TRACKS

OPEN WATER SETS ON FEEDING PLATFORMS OR EDGES OF HOUSES, PLAGE THE TRAP IN ONE TO THREE INCHES OF WATER. PLACE FOUR OR FIVE TRAPS ON A LARGE HOUSE. PLACE THE TRAP STAKE AS FAR FROM THE FEEDING PLATFORM OR HOUSE AS POSSIBLE TO INSURE DROWNING THE RAT.

THE TRAPLINE SHOULD BE RUN AT LEAST ONCE A DAY.

OPEN WATER SETS FOR MUSKRATS AT DEN ENTRANCES. PLACE THE TRAP AT OR JUST INSIDE THE DEN ENTRANCE, WHETHER THE ENTRANCE IS AT THE BANK PROPER OR OUT SOME DISTANCE FROM THE WATER'S EDGE. MUSKRATS CAN BE TRAPPED IN THEIR RUNS UNDER THE ICE BEFORE THE LAKE OR MARSH FREEZES TO A DEPTH GREATER THAN SIX INCHES.

WINTER ISSUE 7 BEAVER

BEAVER

BEAVER POPULATIONS WERE SERIOUSLY DEPLETED DURING EARLY FUR TRADE DAYS, NOW BEAVER STAGING A REMARKABLE COMEBACK IN NEBRASKA. SPECIAL REGULATIONS GOVERN BEAVER TRAPPING: TRAPPER MUST PURCHASE A SPECIAL PERMIT COSTING #5.00, AND EACH PELT MUST BEAR A GAME COMMISSION SEAL COSTING #2.00.

SIGNFELLED TREE AND "BEVER STUMPS"

OAMS

LODGES

TRACKS

BEST SETS ARE THOSE AT DEN ENTRANCES AND LANDING PLACES AND SLIDES. ALL SETS FOR BEAVER ARE MADE UNDER WATER, WITH TRAPS STAKED TOWARD DEEPER WATER. IT IS NECESSARY TO DROWN THE BEAVER IN THE TRAP; THE RUNNING WIRE ASSURES THIS. THE WING OF LOCK SHOULD EXTEND ABOUT 6 INCHES AND MUST EXTEND UPSTREAM. TRAP SIZES NO.3 OR NO. 4 ARE RECOMMENDED.

A GOOD BAIT SET CAN BE MADE AT AN EDDY IN A STREAM WHERE BEAVER ARE ACTIVE, ESPECIALLY IN STREAMS WITH STRONG CURRENT. USE TWO TRAPS UNDER 4 TO 6 INCHES OF WATER AND USE FRESH BRANCHES OR TWIGS OF COTTONWOOD OR WILLOW FOR BAIT. REMEMBER: BEAVER ARE EASILY "SPOOKED" BY CARELESS TRAPPING METHODS.

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA 8 MINK

MINK

OUR MOST PRIZED FUR BEARING ANIMAL, PELT VALUE OVER PAST FEW YEARS HAS AVERAGED ABOUT ^1500. APPROXIMATELY 15,000 MINK ARE HARVESTED ANNUALLY BY NEBRASKA TRAPPERS.

SIGNLAKE AND MARSH OPEN WATER SET. GOOD BAITS ARE FISH, RABBIT, SKINNED MUSKRAT, AND GARTER SNAKE. MAKE SET NEAR SIGN. NO. 3 IS THE PREFERRED TRAP SIZE.

DRY LAND SETS. MAKE SETS IN RUNS. RUNS ARE COMMONLY FOUND IN VEGETATION ALONG MARGINS OF STREAMS AND MARSHES. NO BAIT IS USED. BURY CHAINS AND STAKES AND COVER TRAPS WITH THIN LAYER OF FINE BROKEN UP HAY FROM SURFACE OF THE SOIL.

STREAM OPEN WATER SET. MAKE SET WHERE MINKS, TRAVELLING PARALLEL TO THE MARGIN OF STREAM, ARE FORCED INTO THE WATER BY A STEEP BANK. PLACE TRAP IN LINE OF TRAVEL BY OBSERVING WHERE TRACKS ENTER THE WATER.

WINTER ISSUE

PELTING TIPS

RACCOON

MUSKRAT

MINK

Nebraska trappers as a group lose thousands of dollars due to improper handling of pelts. Here are a few tips that will help you realize full value from your pelts.

1. Whenever possible, do your trapping during the prime season. a. Early winter for mink b. Late winter for muskrat and beaver

2. Skin carefully and correctly. a. Cased handled pelts—muskrat and mink (1) Slit skin along inside surface of hind legs to anal opening; then peel skin forward off the body. Work carefully. (2) Mink require special attention: leave toes and claws on skin by cutting toes off at second joint. Slit tail on under side from anal opening to tip and skin out. b. Open handled pelts—beaver (1) Remove feet and tail. Only a single slit is made, from tip of lower jaw to anal opening.

3. Flesh thoroughly. a. Remove excess fat and flesh to prevent spoilage and "grease burn." Do this immediately following skinning.

4. Stretch properly. a. Do not OVERSTRETCH. b. Factory-made wire stretchers are excellent for muskrats, assuring more uniform pelts and less chance of overstretching. c. Quarter-inch box wood is good for making mink drying boards. Make board to fit pelt; pelt should be taut but not overstretched. A wedge V2 inch high at rear end tapering to y4 inch high at nose end, should be inserted on the belly side. Small nails, two at each side of the base of tail, one in center flap between hind legs, and one in each foot, will help secure tautness of pelt on boards. d. Beaver pelts must be stretched ROUND. Can be rounded for drying by tacking to flat surface or by lacing in a circular framework.

5. Dry in cool, dark, well-ventilated place. a. Do not hang pelts for drying in a heated room. To guard against house damage, hang pelts on wires. Pelts should dry in a week, if conditions are right.

Skunks (including civets): Case skin-side out. Cut off the feet. Slit the tail and dry flat. After slitting hind legs from feet to anal opening, cut around the scent sac and glands and carefully remove them.

Raccoon and Badger: Handle open. Stretch square. Get square effect by stretching and not by cutting or trimming. Slit the tail and dry flat. Do not remove legs.

Opossum: Case skin-side out. Cut off tail and feet.

Fox: Case fur-side out. Slit the tail to the end and dry flat. Do not cut off feet or claws.

Weasel: Case skin-side out. Feet and claws should be left on. Do not slit the tail but remove the tail bone by pulling.

Bobcat (wildcat, lynx cat): Case fur-side out; sometimes open handled. Slit the tail to the end and leave the feet and claws on.

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA 10

BIG SWEDE'S TOW CALL

by Wally GreenIf anyone had told Big Swede that he would enjoy a tow call on a busy day, during a storm, he would call them crazy.

"Big Swede" slammed the gear shift lever down into super-low and eased the foot pedal down. His big tow truck hesitated for a moment . . . and finally bucked through the snowdrift. It had been snowing since last night when he closed the garage. By this morning there was a good 10 inches and it was blowing and drifting. The Omaha weather report had said it would clear off by noon, but the wind would continue to be high all day.

"Had to get this darned towing call this morning," he grumbled. Two tractors to finish today, his helper sick with the flu and the Mrs. expecting him home early for their wedding anniversary party tonight. "Twenty-two years with the same woman — or the same man," he chuckled.

"Well, it's better to be pushed, rather than not have enough work to do," he thought as he shifted back up to high gear. One thing about running a garage, you have your heaviest work in the winter. It wasn't like when he was first married and on the farm. "Farming!" he snorted, "Sure couldn't call that farming in the '30's, not by today's standards, anyway," he thought. "Grasshoppers, dust, drought — and a mortgage," he concluded.

Between the drought and his father-in-law having a stroke, Swede ended up in the garage business. Seemed like the only thing to do at the time, although he didn't like working for a relative. Not that Jim was hard to get along with or work for; but, Swede always liked to stand on his own two feet.

They had lost Jim in 1936, a few years after Swede had started in the shop. Jim had not only started Swede on the path to being a top-flight mechanic, he had also left the garage to Swede and the Mrs.

Things had been tough in those days. Swede had gotten paid more in eggs, butter, milk and chickens than he did in cash. There just wasn't much ready cash but every farmer could at least raise food. Looking back on those days, Swede figured that way of doing business had made him a lot of friends. Why, he had been doing work for many of these same farmers for 20 years now! Surprising, even if he did the best work he know how on their equipment, he thought as he turned east on a section road.

It should be just a little farther now . . . that was McClure's farm back there.

Mac had put the call in and told him this young fellow was broke down two miles east of his place. Said something about him being that new guy in town that worked for the Game Commission. Swede had seen him around. He had even been in at the garage with that new green panel truck for a little work on the brakes. Swede had been busy with a combine at the time and didn't get to meet him. His helper had taken care of the brake adjustment. Swede figured that the lad had his work cut out for him, especially after the past pheasant season. The worst season Swede could remember in recent years.

There he was — broke down on the side of the road. Swede pulled up along side and stepped down from the cab. "Hi, what's the matter. You don't seem to be stuck," he said.

The young fellow, standing by the green truck with a red Nebraska Game Commission sign on the door was wearing rubber snow boots and an old navy foulweather jacket. He walked up to Swede and introduced himself and said, "I lost my radiator hose and didn't want to take a chance on driving into town." "Is that all?" Swede said. "Well, I guess it is just as well you didn't. Could have ruined the engine if you had. I'll have to tow you in," he said as he climbed back into the cab.

Pulling the tow truck up in front of

the stalled truck, Swede climbed down,

loosened the winch line and shackled

the cable onto the front end. Flipping

the winch lever, he started to snug the

truck up to the back of the tow truck.

As he flipped the lever, the young fellow

WINTER ISSUE

11

opened the door of the green panel

truck and pushed the gear-shift lever

into neutral.

opened the door of the green panel

truck and pushed the gear-shift lever

into neutral.

Swede's face got a little red, as he should have though of this. He didn't say anything and kept his eyes on the cable hook. The young man didn't seem to notice anything and it looked as if he had just thought of the gear lever on the spur of the moment.

Back in the cab after getting the truck underway, Swede began to make conversation, "I guess you are that new fellow the Game Commission sent down here — a biologist or something. What are you doing way out here in the country right after a big snow?" he asked.

"I'm just out here to see how the pheasants are doing in this area," he answered.

"Say," Swede said, still trying to forget about the gearshift lever, "maybe you can tell me what happened to the pheasants this year. I only got four the whole season and I was out four or five times," he complained.

"Well, the pheasant population is low, as you probably already know. We don't know all the reasons for it being so low but we have some pretty good ideas about some of the main reasons," he answered.

Swede began to get warmed up now and stated, "If I was running things, I'd close the season for a couple of years and build the pheasants up, then maybe we could have seasons like we used to have. We used to have 30 and 45 day seasons and a daily bag limit of 5 birds. Personally, I would sacrifice two or three years of poor hunting to have hunting like we used to have. I know any real sportsman would feel the same way," he concluded.

The young man sitting beside him said earnestly, "I know most hunters feel the same way you do. They will cooperate to the best of their ability and go all out if a plan has any chance of improving their hunting. The trouble is you can't build up a pheasant population by saving up like you do with money in a bank account. It just doesn't work that way," he explained.

Baffled, Swede asked, "What do you mean?"

"Well, look," the game technician answered, "we know that we lose around 70% of the birds through the winter and only have 30% of the previous year's population for breeding stock in the spring; regardless if we have hunting or not. You see, the birds we take during the season are excess birds; birds that won't be around the next year anyway.

"Wait a minute, son," Swede exclaimed. "All the birds I shot this last season were young, just getting their color. You mean to sit there and say that they wouldn't be here next spring?" he stated emphatically.

"Chances are that some of them wouldn't be," was the answer, "but that is getting down to a pretty fine point and we have to consider the population as a whole when we look at the loss situation."

"But I don't see what could happen to many of those young birds, once they got through the hunting season without being shot," Swede stated.

"Actually it's those young birds that give us the cushion against the losses and provide a breeding population the next spring. But, there is even a large loss of young or yearling birds as there just isn't enough cover, habitat, living space or whatever you want to call it, to carry all of them through the winter. We always go into the early winter with more birds than the land can carry.

"Another factor is the short life span of pheasants. Few pheasants ever live to see two falls as they just don't live that long."

Swede turned his head and said, "I suppose the predators take a lot of them."

"Predators certainly have better hunting as the cover is turned brown, thinned down and crushed with snow. The birds have a harder time to find a hiding place during the winter, except where they are in very good winter cover. We know predators take their share of the birds, but we also know there are more important influences that cut down on the bird population."

Swede became more attentive at this statement and he said, "What other influences do you think are more important?"

"We call it intensive farming," the young fellow said. "If you will remember back in the late thirties, there were a lot of abandoned farms, a lot of fields that never were harvested, and in general, a heck of a lot of cover for the pheasants. You really had the birds in those days. Even at the beginning of the war, there was a lot of land that wasn't being farmed, leaving plenty of living space for the pheasants.

"Back in those days a big operator was a man who was farming 160-200 acres. Now, a big operator can handle 400-500 acres, what with better tractors and implements and the hydraulic lift. He only needs a little help during the harvest and planting season, at that. One thing that he does have to do is consolidate his former small fields into larger units. Where he may have had 40 or even 60 acre cornfields, he now has 80-160 acre fields. Now this has cut down the amount of fence and field borders that offer protection and shelter to the birds. You could guess that from 30 to 50% of this edge cover is gone; it might be even more. You know ,a big field of corn doesn't offer much to a pheasant beside food. They don't get too far into the field as they want to be close to escape cover in case of danger."

Swede though for a minute and said, "Yeah, I have often hunted the outside rows of a field, not going in more than 12-15 rows and that's where you find most of the birds. So you think they stay out near the — what did you call it? — escape cover? I'll buy that because I've seen it. I never thought of the difference farming methods would have on the pheasants, but we sure have had a change at that."

"There might be other farming practices, besides the ones directly affecting the cover, that cuts down birds. For Instance, 'What effect does the wide use of insecticides have on the young chicks?" We know the chicks need to have insects for growing; their whole diet consists of insects. We don't know what the effects are of spraying whole fields with insect sprays during the time when chicks need the insects. That is something to be investigated. In fact we have to do a lot of investigating on all of these things. We might have a general knowledge of some of the things that hurt pheasant populations, but no one has enough investigation completed to know 'How much does each of these influences affect the population?' That is something we are trying to determine. We then have to try and find out what to do about it. Surely, after we understand the problem, then we can work out some better ways of doing things that will give the pheasants a boost and not interfere with our basic land usefarming."

Swede glanced in the rear view mirror to see how the green truck was

tracking around a corner and then

mulled over some of the dope this guy

was telling him. Suddenly he put his

mental finger on something that had

been bothering him the last few minutes. "Look," he said, "first you tell

me that the population is low, then you

tell me that hunting doesn't affect the

population and yet, you folks had one

12

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of the shortest pheasant seasons you've

had in years along with one of the

lowest bag limits. Now, what in the

heck are you, trying to sell me? I

don't know what to believe," he said

in a voice that was begining to get

irritable.

of the shortest pheasant seasons you've

had in years along with one of the

lowest bag limits. Now, what in the

heck are you, trying to sell me? I

don't know what to believe," he said

in a voice that was begining to get

irritable.

The young game technician looked over at him and give him a little smile and said, "I was wondering when you were going to get around to that. You see the Commission has the job of not only managing the game but also it has to manage the Nebraska hunter. You hunters have seven good men that were selected because of their integrity and leadership in showing an interest in wildlife. These seven commissioners are sincere and loyal men that have the best interest of Nebraska hunting and hunters at heart. I'm pointing this out so there will be no doubt in your mind.

"Right now you are wondering if they are just a bunch of bunglers, a bunch of politicians, or a bunch of bureaucrats getting a soft touch from the Nebraska hunter. Right?" the young man stated.

"Well, not that bad, but I sure want to know what the situation is,," Swede said emphatically.

"You stop and remember back in the late spring and early summer — we didn't get much snow last winter and this last summer was dry and hot. If you were out much in the summer you can remember that not even a meadow lark was out in that intense heat, let alone a hen pheasant with a brood of young.

"Mother Nature really pitched us a curve with that heat. We knew that our breeding population was down and the only hope for recovery depended on having a good hatch. You see, we have evidence to indicate that the average hatch size generally increases when a breeding population is low. It seems to be a natural way of compensating for low populations, but we don't know exactly how it works.

"We don't use the total number of successful broods, but the average size of the broods. If we observe a lot of broods that have a large number of young in them, we are safe in assuming that the average brood size is large. When we compare this with the estimated size of the breeding population, we can determine the success of the whole breeding season.

"The trouble last summer was that right up until time to set the season, we didn't see many broods, so we couldn't determine what the brood size was. We knew that things couldn't be as bad as they seemed.

"Yet, all we could tell the Commissioners was the facts: The facts that we had observed were that the breeding population was down and that we didn't have enough information, yet, to know what the brood success was going to be.

"If we had a good brood success, in spite of the low breeding population, we could expect a fair fall population. But, on the other hand, if we had a poor brood success along with the poor breeding population, the fall population would be extremely poor, even when compared with the 1953 fall population.

"That was all we actually knew, at the time; and was all we could tell them. The Conservation Officers, farmer cooperators and everyone concerned had the same to report. No matter what source of information we turned to, we just couldn't get any other story, up until the time to set the season.

"Now the Commissioners have to depend on us for the information which they use to set the season. In the middle of the summer and until the week they set the season, they were literally deluged with petitions, letters, delegations and personal contacts by people in their areas. All of them requested closing the season or at least to have a very short season."

"I remember our local club sent a letter to Lincoln," Swede interjected.

"They made the decision for the 1954 season on the basis of hunters' desire and on the basis of the available information provided by the commission personnel.

"Later, when the August rains came, the broods began to move around. Actually, the brood success was good, but we didn't know it until this time. True, some of the birds were from a late hatch and this seems to explain the reports during the season, as many hunters got some very young birds.

"We would have been worried if they didn't get many young birds, as that would have indicated we had a poor hatch and wouldn't have much of a carry-over for the coming breeding season."

"Well, I guess your commissioners had to have a short season. I know our wildlife club was still quite put out, even when the short season was set. When we got out in the field in the fall and saw some birds, more than we thought we would see, it looked better," Swede agreed.

"Well, that is how it happened. We didn't have proof that there was a good hatch at the time we set the season. We couldn't set the season on what we thought was going on in the field, the hunters wouldn't stand still for that and what's more, we don't work on the basis of What we think,' but what we know, especially when setting a season."

They were now getting into town and Swede was quiet for a few minutes as he swung the tow truck through traffic. Soon he swung into the drive to the door of the garage and stopped the truck. Quickly he climbed down and opened the garage door and came back to the tow truck and pulled inside.

He unhooked the Game Commission truck and climbed inside to drive into the stall, as he knew it wouldn't hurt the engine to pull the panel a few feet. As he shifted into gear, he again thought of his forgetfulness of trying to pull the truck when it was in gear.

As he climbed out of the cab, the young game technician had walked up to him and said, "I haven't had breakfast yet. I'll pick up the truck in about an hour, if that is all right with you?" Swede said it would take only about 20 minutes for him to fix the hose and put new anti-freeze in. "I'll have it ready for you," he said. "Thanks for giving me some information on the pheasants; it was pretty interesting. I guess that even if I have been hunting around here for 20 years, I don't know all the answers about pheasants."

The young fellow grinned and said, "Well, even if pheasants are our business, we surely don't know all the answers either. No one does. We have to look for a lot of answers and we have a long way to go before we understand all the problems. We might never understand all the problems, but we hope to find out some of the main ones and also find a way to correct or minimize them."

After he said that, he turned and started up toward the front of the shop. Swede started to turn toward the panel truck when something on the back of the fellow's old navy jacket caught his eye.

MMM 1/c—Motor Machinist Mate, First Class! His nephew had been a motor machinist mate during the war.

"No wonder the lad reached in and shifted the truck out of gear," Swede grinned. "Here I was trying to tell him how to run his pheasant work because I've been hunting them for twenty years. At least he didn't try to tell me how to tow his car. It's like Jim used to say when I first started in the garage — You never get too old to learn something new," Swede said to himself.

WINTER ISSUE 13

WILDLIFE in one reel

Fish Management Means... BETTER FISHING FOR NEBRASKANS

by R. W. Eschmeyer R. W. Eschmeyer, pioneer fisheries worker, now with the Sports Fishing Institute, begins the first of a series of articles on fish conservation. Here is the story of the development of a new science that is the only hope for providing better fishing for you and your children.FISH conservation has had an interesting development. Here are some of the major points in its evolution, shorn of the many qualifying statements which would normally be made if space permitted. The evolution is interesting partly because of its uneven development; in some states it has progressed much farther than in others.

In pioneer days, fish were abundant. The land had been only sparsely settled by Indians, and their methods of taking fish were crude and inefficient enough to prevent depletion. So, in the early days there were plenty of fish to serve as a major supply of fresh meat for the settlers. There were no conservation measures. None were needed.

RegulationIn time, there was local evidence of depletion, especially where easily caught, spawning runs were harvested extensively. Locally, some regulation of the fishery seemed desirable. Emphasis was on allowing brood stock to spawn. It was felt that there should be closed seasons at spawning time and that the fish should not be taken until they were big enough to have spawned once. There was a tendency, too, to limit the individual catch. The regulations, therefore, involved closed seasons, size limits, and catch limits. The emphasis was strictly on regulation. The laws were imposed by the legal bodies —generally by state legislatures.

Enforcement called for a special setup, usually consisting of a chief warden and field wardens. These individuals were political appointees. The warden jobs were a welcome addition to those politicos who needed to find a pay check for their faithful campaigners.

Gradually, more and more laws were imposed and more wardens were hired. Since there were no fact-finding programs, the regulations were made more or less arbitrarily.

In time, there was a new development. It was found that fish could be produced in hatcheries and rearing ponds. The artificial hatching and stocking of fish fry became a craze. The federal government and the states built more and more hatcheries.

Since fish spawned successfully if given an opportunity, producing fry in rearing ponds was a simple matter. The discovery that trout eggs could be stripped out and artificially fertilized led to a simple procedure for producing trout fry. After a very little experience, political appointees could handle the hatcheries. Here, then, were more jobs for the faithful.

The expanded "fish conservation" program called for the spending of considerable sums of money. To pay for the costs of the state programs, anglers were required to purchase licenses. Here the taxation was directly on the "consumer." The income from licenses was generally turned over to the general fund. The legislatures then decided on how it was to be used. Necessarily, due consideration was given to the political values.

The Peaceful DaysConservation became a simple routine. If sportsmen in a locality became dissatisfied, a load of hatchery fish fry usually lulled them back to complacency. If this wasn't enough, they might be given a few additional cans of fish, or a few new restrictive laws would be imposed. If the anglers were especially hard to please, they might be given an added warden, or a replacement for the warden already on the job! These were the peaceful days of fish conservation. The political appointes had only one major problem to please the voters. For quite some time they had a simple means to that end—more fish fry, more regulations, more wardens.

There was only one thing wrong with the "fish conservation" program it didn't help fishing! There were harder days ahead.

Sportsmen, dissatisfied after a few poor days afield, turned to other panaceas. Some felt that there was too much inbreeding, and asked for new stocks. Some blamed the predators, with predator control programs resulting. Almost invariably the anglers wanted any species introduced which were not already present; a program of introducing all sorts of species in all sorts of waters followed. There was argument over which laws should be imposed, leading to the passing of innumerable local laws, imposed by the legislature to please local groups. The regulations became highly complicated.

The political appointees were having more and more difficulty in their one major job-keeping the anglers contented.

Trouble ShootersFinally, and perhaps in desperation, they employed biologists, usually professors who had time to spare from their teaching during the summer months. The biologists served a worthwhile purpose from the start, as trouble-shooters. The administrator could restore contentment, momentarily, by sending the biologist to trouble areas, and by indicating to the public that "we are studying the problem."

But, the biologists weren't content

with the "trouble-shooter" role. Typical of their breed, they were conscientious people who wanted to find the

answers. In time, they found some.

The answers, though, were embarrassing to the administrators. They tended

to demonstrate that the methods of "fish

conservation" which were in vogue

were ineffective. They discovered,

more and more, that the medicines in

use did not cure the ailment. But they

failed to come up with new remedies.

It was an embarrassing period for both

the biologist and the administrator, as

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

16

well as for the hatchery man and

warden whose products or services

were now subject to question.

well as for the hatchery man and

warden whose products or services

were now subject to question.

Meanwhile, the public was inclined more and more to rely on specialistson doctors, lawyers, engineers, agricultural experts. So, naturally, the public was beginning to place reliance on the trained fishery experts. This led to internal difficulties. The politically appointed administrators, wardens, and hatchery men, who originally considered the biologists with their big words and their devotion to their jobs to be an interesting novelty, now began to think of these specialists as potential competitors for their jobs. The biologists were openly ridiculed. But, they stuck to their knitting. In some instances the ridicule was deserved; many biologists failed to recognize the human angle. Some were impractical. Some were obviously deficient in "bedside manner."

The PastureMost important was the observation that a lake or stream is really a pasture, with extremely prolific "livestock," and with the rate of growth depending on the amount of food varible. It was found that fish needed more than just water; that other conditions needed to be favorable, too. It was discovered that a small fish wasn't necessarily a young fish—he might be an underfed old-timer! The technical fellows learned about food chains; a bass eating small fish which eat insects which subsist on microscopic food isn't equivalent to a sheep eating grass. It's equivalent to a super-predator eating wolves which eat sheep which eat grass. This explained quite clearly why our lakes and streams couldn't be "half fish and half water!" The biologist gradually learned many things even though they couldn't find a simple answer to the question of how to give "ideal" fishing to all anglers.

AdministratorsMeanwhile, the internal feuding led to interesting developments. In some states the political administrators were replaced by other people. Hatchery men were given the top fishery jobs in some states, wardens in others, and biologists in still others. In every intance, some individuals developed a broad viewpoint and did a good job. Others retarded conservation in their states. Today, we have administrators in all these categories.

The political appointee doesn't object to good conservation, but he also tends not to promote it. His main interest is in keeping the voter happy and in hanging on to his job. Since conservation education might lead the public to suspect that he isn't competent, he generally is opposed to public enlightenment.

The one-time warden, as an administrator, may tend to over-stress enforcement. Often, he tends to object to fact-finding, to education, or to change. He doesn't want to change the "status quo."

The fishery administrators who came up the hatchery ladder naturally tend to favor stocking. Some do everything possible to retard progress; others are doing a good job in the administrative capacity. In several states these men have definitely opposed fact-finding. They may have one or a few trained men on the staff, because of public demand, but the men are held down and some of their findings are kept from the public. These hatchery men spend most of the funds on more and more stocking. A few even go in for put-and-take warmwater fish stocking, without letting the public know that the cost of raising bass to catchable size in hatcheries is exorbitant. These "administrators" usually have very limited fish conservation education programs. They don't want an enlightened public for obvious reasons. Where they have been in power for years, the public is usually poorly informed, and even the commissioners may not know that their fishery program is an unenlightened one. The states tend to be backward in fish conservation. As indicated above, in some states the hatchery men, after being made top fishery administrators, keep up with the times and have progressive set-ups.

The tendency is, more and more, to put formally trained fish men in charge of the state fishery programs. These men, trained as biologists, may have trouble in public relations, but in general the programs which they advocate are the most progressive.

In the interesting evolution of fish conservation the need for formally trained fish men is now generally accepted—following the same evolution as we have had in medicine, engineering, and other specialized fields.

The Present PictureAs for the current fish conservation picture, enough is known now to present it rather graphically. Here it is:

1. We have more and more anglers. Fishing pressure increases constantly.

2. A lake or stream will produce only a limited amount of "livestock." The average acre of water in the United States probably supports only about 100 pounds of fish.

3. Of these fish, only a portion are of the size or species wanted by the angler. In many waters the desired fish are in a minority.

4. Of the available supply, only a fraction can be caught. The hook and line is inefficient. This point will be easily appreciated if you try "fishing" for rabbits—baiting your hook with a piece of carrot and waiting (hidden) for a rabbit to take it! On many of our big waters the catch is only a small fraction of the available supply.

5. Because of siltation and pollution, many waters can no longer support as big crops of fish as they once did.

In view of the above observations it's easy to see why the average catch gradually dropped with increased fishing pressure. It dropped to where the average catch was less than one fish per hour, and the average fish was less than ten inches long.

Now, we have growing evidence that fishing is improving. The trained fishery fellows are learning, more and more, how to manage our waters. They are becoming more efficient in handling our fish management tools: (1) stocking, (2) regulation, (3) environmental improvement, (4) controlling fish populations, and (5) creating more fishing waters.

To use the tools still more effectively we need more fact-finding and a more enlightened public. Consequently, in those states which are trying to progress rapidly the emphasis is on research and on conservation education. If your state isn't emphasizing these two items, it's not doing a good job.

There are still problems, many of them, but we're now optimistic about the future of fishing in some states. We're less optimistic about some others because they have not yet moved far in their fish conservation "evolution."

In future issues, we'll discuss the fish conservation "tools," one at a time.

CORRECTION The Outdoor Nebraska TV show is on Channel 12, KUONTV, Lincoln, instead of KOLNTV; as stated on page 28. The show, directed at youngsters, is 10:30 a.m., every Saturday. WINTER ISSUE 17

WHAT'S HAPPENED TO NEBRASKA PHEASANTS? WHY DON'T WE HAVE BIG POPULATIONS LIKE WE USED TO?

By Dr. Henry Sather General Reasons For Pheasant DeclineWE ARE the last to deny: Nebraska pheasant populations have been on a downhill grade during the past several years. Everyone is deeply concerned about this unquestionable decline in pheasant numbers. How can we account for this wasting away of our pheasant populations? That is the all important question.

Many say that the 'coon is the culprit, others sincerely believe that the skunk is the responsible party, others the fox, and still others over-shooting. No one can deny that these are enviroment factors that influence pheasants; however, it is important that we realize that none of these factors fit into the categories of food, cover, or water—the basic requirements of animal life.

Basic NeedsGive any particular type of animal its own special combination of food, cover, and water and it will produce a harvestable surplus and survive in the face of almost any emergency condition. This is not hearsay; it is known to be true. It is also known that a deficiency in any one of these basic requirements—food, cover, and water will serve to limit the size of the population despite an ideal status of the other two. For example, a shortage of pheasant nesting cover will serve to limit the number of pheasants despite an abundance of food, water, and other types of cover.

The food, water, and cover requirements of pheasants—or all animals, for that matter—are confoundedly complex.In general we know that food must furnish essential vitamins, proteins, and minerals in addition to fat producing substances; various types of cover are needed for nesting, roosting, loafing, escape, etc., and they must be arranged in a certain pattern; water, in the form of dew or standing water, is needed at the right times and in the right places in relationship to cover and food. We know what pheasants require in a general- way, but many of the details are missing.

Effect Of Heavy FarmingIntensive use of the land by man primarily for agricultural crops demands more than just a general knowledge of the pheasant's basic requirements. Let's face the cold hard facts: we can't manage Nebraska land just for pheasants. Pheasants are a rather insignificant—insofar as agricultural interests are concerned—by-product of the land. To obtain good pheasant populations under such circumstances, more than a general knowledge of pheasant requirements is needed. We need to know specific basic details.

Let us delve a little deeper into the pheasant food question. Is there any possibility that fundamental changes have taken place in this basic requirement over the past several years? We know that young pheasants require a good source of protein for proper development.

Insects are rich in protein, so young pheasants feed almost exclusively upon insects. Insect killing chemicals have enjoyed a tremendous boom within recent years—this boom has coincided with our pheasant decline. Have these insecticides seriously affected the basic food requirements of young pheasants? This is a problem of the first magnitude, because it involves a basic requirement for life.

Calcium RequirementAdult pheasant hens, like domestic chicken hens, require a good source of calcium for egg production. It is known that none of our major cultivated crops t furnish enough calcium for egg production. Pheasants living in the wild derive most of their calcium from weed seeds and grit.

That being the case, what effect is the noticeable trend toward grassyaway from the weedy—fencerows, and the widespread use of weed-killing chemicals having upon this basic food requirement of our breeding stock? Here is another problem of the first magnitude, because it also involves a basic requirement for life.

If there is some doubt in your mind as to whether these changes have actually occurred, revisit some of your favorite hunting grounds of the 1930's and early 1940's. Give them a good look: you will notice that some striking changes have taken place.

We have literally just skimmed the surface of the changes that have taken place in food requirements, but let us now go into the subject of cover requirements. Have changes in cover occurred since the pheasant "boom" years of the early 1940's?

Farming ChangesNo one can deny that the farm economy has undergone tremendous changes since those years. Higher prices and the development of more

(Continued on Page 20) 18 Plans To Get More Details

by

Phil Agee

and

Max Hamilton

Plans To Get More Details

by

Phil Agee

and

Max Hamilton

THESE are questions that every field man encounters daily. These are questions that must be answered, in part at least, with "We don't really know." There are many serious gaps in our knowledge of the pheasant.

It is obvious that successful management of anything must be preceded by rather thorough understanding of that which is being managed, whether it is a drugstore, a field of corn or a population of game birds. Failure to have this understanding will usually lead to discouraging results and inefficient use of funds.

Detailed StudyRealizing this, the Game Commission has begun a study intended to provide some of the needed knowledge. Answers will be sought on many aspects of pheasant management such as these:

1. What are the shortcomings in the pheasants' habitat? What would we have to change to benefit the pheasants most? Is there insufficient winter cover? Is the food supply inadequate? Are there too few cocks, or too many? Is there a shortage of nesting cover? Are predators or hunters taking too many of the birds? Or is one of the many other needs of the pheasant to blame? We must know this before we can carry on the most profitable management.

2. Another problem to be probed is "How effective is stocking and what is the most economical method of stocking?" There are several approaches that may be taken when we try to increase pheasants by stocking. These include fall releases of adult cocks, spring releases of mature brood hens, and summer releases of immature birds. By which method do we get the best results for the sportsman's dollar?

3. A third point to be studied is the life history of the pheasant. We need to know what the birds are doing at any particular time of the year; the cover types they choose, the particular foods they utilize, the places they roost at night and loaf during the day, the size of the home range, and even the extent to which they tolerate crowding by other pheasants.

We expect to gain additional information from these studies also. Improved trapping and marking techniques will probably be learned so that any future study can be carried on with a minimum of effort and expense. Better census methods may also be found so that we can better evaluate our annual pheasant population and adjust the harvest to it.

LocationAs a place to carry on this work, three study areas have been established in Clay and Fillmore counties. This portion of the state has been chosen for three reasons: First, it is in good pheasant range. This is necessary to insure a good supply of birds to work with. Second, considerable hunting is done in these counties, providing a means of recovering marked birds and giving the investigators a chance to measure the effects of hunting. Third, fairly large tracts of state-owned land are located there and serve as a nuclei of two of the study areas.

Each of the three study areas occupies about nine square miles. The first is located near Harvard, Nebraska, and includes the old Harvard Air Base. Here various methods of stocking both gamefarm and wild-trapped pheasants will be tested and several techniques of releasing will be checked to learn how the birds can best become adapted to their new surroundings. As each experiment is conducted, the total pheasant population of the area (including native and planted birds) will be followed closely to determine the net effect of each particular releasing technique or stocking method on the population. This way, each method can be evaluated in terms of pheasant increases per dollar spent.

Land-Use AreaThe second area is similarly located around the old Fairmont Air Base, just south of Fairmont, Nebraska. Here populations will be followed so that the effects of changing land on pheasants use can be learned. Land uses to be analyzed will include various arrangements of crops, the use of fertilizers, and the inclusion of waste areas, weedy fencerows and specially planted plots to provide cover. Working closely with the Soil Conservation Service and the State Agricultural College, attempts will be made to work out new farming practices which will benefit both farmers and pheasants.

The third area, located five miles north of Edgar, will be used as a check or control area. Following the pheasant population on this area will reveal whether or not fluctuations on the other two areas occurred as a result of the stocking, habitat manipulation or occurred naturally.

(Continued on Page 20) WINTER ISSUE 19 General Reasons

For Their Decline

(Cont- From P. 19)

General Reasons

For Their Decline

(Cont- From P. 19)

efficient power machinery have spearheaded these changes. The outcome has been a noticeable trend towards more intensive and cleaner farming. It has become foolish for a farmer to allow any land to lie idle that is suitable for crop production. During recent years it has even paid to harvest low yield fields that would have been left unharvested during the dark years of the 1930's and early 1940's.

These changes in farming practices have had a tremendous impact upon game cover. They couldn't help but have an impact, because fundamentally the pheasant is a farm game animal. The trend towards grassy fencerows, mentioned earlier, has eliminated a striking amount of good weedy cover. Within very recent years a great many fencerows have been eliminated completely. Woody field borders—usually in the form of osage orange hedge—are being pulled, pushed, and cut out faster than we can ever hope to replace them.

Weedy and/or wooded gulleys are being bulldozed-in and leveled off to fit into the crop production picture. Almost every inch of suitable—if not suitable, attempts are made to make it suitable—ground is being utilized for crop production. These things have brought about changes in pheasant cover, a basic requirement for life.

See For YourselfWhen analyzing the cover situation in your own area, keep this in mind: fall cover is deceiving, late winter and early spring are the critical periods. Food and cover are both at a premium during late winter and early spring. Conditions prevailing then will govern whether or not the land can support sufficent numbers of birds to produce a harvestable surplus for the 'coon, skunk, fox, and the hunter.

Like all animals, the pheasant is a complex organism living under extremely complex conditions that are ever changing. I certainly do not want to imply that predators—actually the hunter should be included in this category—can be completely ignored insofar as pheasants are concerned, but I do want to imply that more important basic factors are involved when pheasants are in trouble.

Our pheasants will live and thrive where food, cover, and water conditions are right. If we devote most of our attention to these, the basic requirements, we will not be disappointed. Killing predators or regulating hunting pressure cannot remedy basic requirement deficiencies.

Plans To Get More Details (Cont- From P. 19)The study, although in its infant stage has gotten underway. A cooperative agreement has been drawn up and signatures of nearly all of the land operators involved have been secured. Base maps and maps of exist-land operators involved have been seing cover and crops have been made for each area. Preliminary censuses have been taken on the three areas to determine the comparability of the pheasant populations. Equipment for the study has been obtained and trapping and banding of pheasant is beginning.

Much of the equipment is of a very special nature. An example of this is the trapping equipment which consists of a truck rigged wtih floodlights and spotlight and manned by a team of three to five men. The design of the equipment and procedure used in this type of trapping was patterned after that of South Dakota biologists who perfected it and have used it with amazing success.

The technique for marking the birds (see picture) is new in America. It was developed by English researchers and was first used in the United States about a year ago when it was successfully used on quail by the investigators assigned to this project. It is expected to be fully as successful when adapted to pheasants.

In a few months two of the external signs of this field work will be noticed. The first will be pheasants wearing numbered plastic markers indicating that they have been handled in the field work and are supplying data. We will be anxious to be notified of the date, location and identification number of each marked bird seen.

The second will be the presence on the three study areas of signs designating them as "Wildlife Research Areas" with "hunting by permission only." This is where the sportsman enters in. He must contact the farmer for permission and instructions before any hunting is done on the land. We must know how many hunters go on the areas and how much game comes off. The sportsman's cooperation is imperative to the success of the program.

In all areas it is up to each farmer to determine how many hunters go on his land and which parts of the farm may be hunted without endangering his property.

The Commission is certainly grateful to the farmers and land owners who gave their permission to include their lands in the study areas. Their interest has illustrated to us the concern of Nebraskans for the welfare of the pheasant and pheasant hunting.

We are ready now to start the long tough job in the field: recording changes in the various food sources and cover type; making notes on the sex, age, weight, etc., of individual pheasants; measuring mobility; nest success; survival of young and a hundred other phases of the pheasant's private life. These are data, the stuff that when analyzed and interpreted, can provide answers to questions that can be answered no other way.

Only after getting these answers can we hope to manage pheasants on a business basis—that is, having the most efficient harvest that will maintain a good sustained yield in future years.

Following are the regional names of a common duck that migrates through and sometimes nests in Nebraska. How many of these names do you have to read before you can bring the picture into focus?

Biddy; blackjack; blatherskite; bluebill, bobber; booby; booby bristletail; broadbill; broadbill dipper, brown duck; brown teal; buck-ruddy; bullneck; bumblebee buzzer; bumblebee coot; butterbowl; butterduck; canard roux (russett duck); chunk duck; coot; creek coot; dapper; daub duck; deaf duck; dicky; dinky; dipper; dipper duck; dip-til diver; dopper; dumb bird; dumpling duck; dummy duck; dunbird; fool duck; goose teal; goose widgeon; greaser; hard head; hard headed broadbill; hard tack; heavy-tailed duck; hickory head; Johnny Bull; leather-back; leather-breeches; light - woodknot; little soldier; marteau; mud dipper; murre; muckrat duck; noddy paddy; paddywack; pintail; quilltail coot; rook; rudder duck; salt-water teal; shot pouch; shanty duck; sinker; sleeper; sleeping booby; sleepy broadbill; sleepy-jay; soldier duck; spatter; spatterer spiketail; spinetail; spoonbill; spoon-billed butterball; steelhead; sticktail; stiff tail; stiff-tailed widgeon; stiffy; stub-and-twist; stubtail; toughhead; water partridge; widgeon; widgeon coot and wiretail. (Answer On Page 25)

20 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

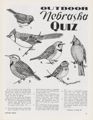

All of the birds in this issue's Outdoor Quiz are common in the Nebraska winter scene. Some are colorful, some are drab, and some are easy and a couple are hard to identify.

See if you can match the following paragraphs with birds and their names.

A. This bird is a small gray and black migrator that spends part of the year in Nebraska. He is one of our typical winter birds. No

B. The single dark spot on this bird's breast separates it from the rest of the sparrow family. A migrator, they are common in Nebraska during the winter. No

C.A common bird in Nebraska, but seen mostly in the winter in small flocks on the road. Very numerous but seldom noticed by most people. His distinctive horns or tufts on his head are a give away. No

D.Every Nebraskan should recognize this bird. Usually associated with the spring and summer time, many of them winter over in the state. No

E. This bird is a beautifully colored bird, but his voice certainly doesn't match his color. He has one of the most disconcerting and noisy voices of any of our birds.

F. This is also a brilliant colored bird, both pleasing in appearance and voice. He is commonly associated with the winter scene, because of the brilliant contrast of his color with snow. (Answers on Page 22)

WINTER ISSUE 21