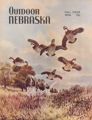

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA FALL ISSUE

1954 15c

Outdoor NEBRASKA

Vol. 32, No. 4 EDITOR: Wallace Green Artist C. G. Pritchard Circulation Marjorie French Leota Ostermeier COMMISSIONERS Donald F. Robertson, North Platte; Harold H. Hummel, Fairbury; Frank Button, Ogallala; Bennett Davis, Omaha; LaVerne Jacobsen, St. Paul; Floyd Stone. Alliance; Leon Sprague, Red Cloud. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: Paul T. Gilbert. CONSTRUCTION AND ENGINEERING DIVISION: Eugene H. Baker, supervisor. FISHERIES DIVISION: Glen R. Foster, supervisor. GAME DIVISION: Lloyd P. Vance, supervisor. INFORMATION DIVISION: Wallace Green. LAND MANAGEMENT DIVISION: Jack D. Strain, supervisor. LAW ENFORCEMENT DIVISION: William R. Cunningham, supervisor. LEGAL COUNSEL: Carl H. Peterson. HOW TO SUBSCRIBE OUTDOOR NEBRASKA is published quarterly at Lincoln, Nebraska, by the Game, Forestation and Parks Commission. Subscription rates are $1.00 for two years and $2.00 for five years. Single copies are 15 cents each. Remittances must be made in cash, check or money order. Send subscriptions to OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, Department C, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska. CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please notify this department immediately of any change of address to assure prompt delivery of the next issue to the new address.Editorial

W. O. Baldwin, Hebron Retiring Chairman

The official term of Commission Chairman Orville Baldwin, attorney from Hebron, Neb., ended September 7, 1954. Commissioner Baldwin's five-year term has been a productive period in game and fish management as well as improvement in the State parks. Mr. Baldwin has been a sincere and conscientious worker in helping to achieve these improvements.

During his Chairmanship, the Commission has launched its new reorganization and redistricting plan which has brought to the Commission and Chairman Baldwin enumerable problems which have been studied in detail. The end of Mr. Baldwin's term finds this reorganization plan working smoothly with a great addition of benefits to the people as well as a completely new and improved method of analyzing game and fish populations and the attacking of the enumerable problems involving Nebraska wildlife.

The members of the Commission, its personnel and the wild lifers of Nebraska will miss Commissioner Baldwin's leadership. However Mr. Baldwin has assured all of his friends of his continuing interest and active participation in all wildlife activities which will be of benefit to the State of Nebraska.

The Commission members are looking forward to a more productive period in the history of this Department due to the adequate foresight which has been established for this advancement. All material appearing in this magazine may be reprinted upon request.

NEBRASKA FARMER PRINTING CO.. LINCOLN. NEBR

Paul T. Gilbert Executive Secretary

OUR BEST TOOL HABITAT IMPROVEMENT

by Wade HamorEACH of us accepts the fact that our lives would be short and very miserable without adequate food and shelter. An inadequate supply of either in any part of the world results in a low human population. In other words, the land which is capable of producing only minimum food and shelter conditions can support only a small number of people in comparative comfort and the excess must either move out or die. The same applies to all living things—plant and animal; plants, of course, being immobile, have no choice, upon finding themselves in an unfavorable environment, but to die.

Wildlife populations throughout the world are abundant or scarce, present or absent, depending upon the environment. Elephants, for instance, occur in India, but we would not expect them to thrive in the wild in Nebraska because of adverse climatic, food and cover conditions. Within our own state, the sharptailed grouse occurs in the grasslands of the Sandhills but not in the southeastern portion of the state. Why not? Generally, for the same reason the elephant is not found there. The environment is not acceptable to the species.

To work this story even closer to our game problems in this state, let's consider the bobwhite quail. This fellow's whistle is heard over most of Nebraska, except in the far northwest. The nucleus of the quail population is still in the southeastern corner, but living conditions have become acceptable to him along the rivers and streams stretching westward and as a result the numbers of this bird now living in the state, have increased.

What is known as marginal quail territory now has a fair supply of the bobwhite. Weather, food and cover conditions have been favorable for this fellow with the resulting increase in population. The time may come when these factors will turn against him and his descendants will either die or be forced to return to locations providing more favorable living conditions.

Pheasant populations respond to the factors of weather, food and cover in the same manner. Climatic conditions in this region are favorable to the pheasant, as proven by his continued presence here year after year.

Local weather conditions, on the other hand, play a large role in population densities. Winter food, generally, has not been a problem since mechanical harvesters leave large quantities of wheat and corn in the open fields. Such fields usually have open areas which have been blown free of snow, making the grain available to the birds throughout the winter months.

Available food during the remainder of the year is becoming more of a problem as a result of heavier usage of herbicides and insecticides. Young birds are almost completely dependent on 'insects for food during midsummer. This supply, of course, is destroyed wherever insecticides are employed in sufficient quantities to effectively reduce the insect populations.

Multiflora Rose is used here as a living fence to separate field borders on the contour.

Herbicides are gaining popularity

among farmers as well as the various

state and county agencies concerned

with weed control. The sprays are an

efficient means of weed destruction;

therefore their popularity. The real

problem arises when they are used excessively. Those odd corners which are

to be found on many Nebraska farms

FALL ISSUE

3

and which are of no particular value

for crop production should be allowed

to produce a crop of weeds in the interest of erosion control and wildlife

production. Usually the sunflower,

giant ragweed and the smaller species

of ragweed are among the first plants

to invade such areas.

and which are of no particular value

for crop production should be allowed

to produce a crop of weeds in the interest of erosion control and wildlife

production. Usually the sunflower,

giant ragweed and the smaller species

of ragweed are among the first plants

to invade such areas.

These forbs are a real value to wild birds as a food and cover crop. They are easily controlled by cultivation on other parts of the farm, so pose no problem to the farmer from that standpoint. So far as is known, these plants harbor no destructive insects and mowing or spraying such areas only bares the ground so that erosion may take over and wildlife populations are driven out. If and when noxious weeds invade such locations, then spraying or mowing is the logical answer. Spraying for all weeds throughout the growing season not only destroys the wildlife habitat and forces these populations to move to more acceptable locations but also costs the farmer a great deal of money and supplies no benefits in return.

The war years created havoc with wildlife habitat as many acres of land, which formerly had been considered unfit for cultivation, were put to work producing crops. The cost to the land was high because of soil erosion and at the same time, wildlife was crowded into even smaller living quarters. Weather conditions were favorable to good hatching and brood rearing during those years and population figures climbed somewhat. Successive population peaks occuring at about 10-year intervals are seldom as high as the preceding ones, indicating that the numbers of birds are steadily declining.

Back in September, 1937, the Congress of the United States took note of the steady increase in hunting pressure and the declining habitat conditions. The wholesome recreational value of this natural resource was recognized. As a consequence, the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Act, as amended and commonly known as the Pittman-Robertson Act was signed into law September 2, 1937. This Act directed that the eleven percent tax on sporting arms and ammunition paid by the manufacturers was to finance a project, which would directly benefit wildlife populations. The monies could be used by the states for land acquisition, research and investigations, habitat restoration and for financing project to coordinate all of the foregoing activities.

A major part of the money allotted to Nebraska has gone into the habitat restoration program which was initiated in 1939 in the southeastern part of the state. By 1941, the project had expanded to include south-central and northeast Nebraska. The war years followed and the project gathered dust until 1947 when men again were available to revamp the program. A new set of specifications was written, using the knowledge gained from prewar experiences.

The new program outlined the necessity of fencing all plantings to exclude livestock since it was known that native vegetation would return to provide valuable cover in addition to any new planting done. Also, cattle, by their rubbing habits, destroy the lower limbs of trees and take away the low ground cover so essential to wildlife.

Future habitat plantings will be made by the Operation Crew located at each District Headquarters.

Knowledge of the exact type of cover needed was desired and a variety of plantings were established to attain this goal. It was decided at this time, however, to concentrate on winter cover plantings until the experimental plantings had matured and a more definite habitat restoration program could be mapped.

Also, it was considered essential that your Game Department demonstrate the best methods of planting, fencing and cultivating the sites for the benefit of the landowners in order that those who became interested could be correctly advised of suitable planting and cultivating methods to provide maximum tree survival.

Now, seven years later, it is known that the original goals were sound and that the desired effects have been reached under that program. The experimental plantings have reached that stage of maturity whereby their effects can be measured for best game habitat values.

From these plantings, your game commission is reasonably sure that development of winter cover sites throughout the entire state is not nec essary, and also the planting pattern of future sites of this nature should be changed somewhat. In the southeastern part of the state, a less expensive and smaller size planting will meet the primary wildlife needs, it has been found.

This past experience also has shown that certain species of trees and shrubs can be eliminated from the order list and, most important, that sportsmen and farmers in general have learned the need for habitat restoration if they, and those who follow, are to enjoy the thrill of a hunting trip when harvest time rolls around.

The Game Department, in order to confirm some of the conclusions reached during the interim since the program's initiation, is conducting a research program which has for one of its goals the determination of minimum habitat requirements of the pheasant.

The current Habitat Restoration

Project has incorporated all the facts

gleaned from the past fifteen years of

experience in this field. This project

was ready for the reorganization which

the department is currently undergoing

as experience indicated the necessity

of getting trained men into the field to

work with farmers, sportsmen's organizations, the Boy Scouts and other

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

interested groups. This, for the most

part, has been accomplished by making

our trained personnel available to

about five times the number of people

as compared to the old Game Commission setup.

interested groups. This, for the most

part, has been accomplished by making

our trained personnel available to

about five times the number of people

as compared to the old Game Commission setup.

Since 1939 approximately 3000 plantings, representing several million trees and shrubs, have been established on Nebraska farms for the purpose of restoring habitat. The plantings were established by Game Commission crews beginning with one crew in 1939 to ten crews in 1954. At a glance, one can see that Commission personnel could never do the job which must be done if a complete job of restoration is to be accomplished throughout the state. The cooperation of all farmers, sportsmen's clubs and other interested organizations must be solicited if acceptable habitat conditions are to reappear on the land.

Your Game Commission has experimented in the field of habitat restoration for the past fifteen years and has collected the information from the experiences and research of other states and is now ready to assist all of those who are interested in getting the restoration job done. This Department will continue planting trees and shrubs for as long as is necessary or until private individuals and organizations can take over.

In addition to this, trees and shrubs will be supplied to those who have acceptable planting sites along with recommendations as to just how the planting should be accomplished to secure best results. Our Land Managers, one being stationed at each of the new headquarters located at Alliance, Bassett, Norfolk, North Platte and Lincoln, will be available at all times to inspect proposed development sites and to offer recommendations as to the best and most economical method to accomplish the work.

Before approving a site for planting, the Land Manager will assure himself that a planting is needed and that the interested person has the ability and means of building a fence with materials furnished by the Game Commission, if a fence is needed.

He will check to see that he has the ability and means of properly caring for the planting after it is planted, which includes the cultivation so essential in Nebraska. In addition, he will ask that the landowner sign an agreement in which he agrees to care for the planting for ten years. The "care of the planting" is defined as cultivating for two or three years or as long as is necessary and excluding cattle from the tree plot during at least the term of the agreement. Fencing materials are not supplied for multiflora rose plantings since all that is usually required is an electric fence to protect the plants for the first year or two during the period when the plants are exposed to trampling by cattle.

To elaborate a bit farther, the Land Manager has a method by which he can determine the approximate cover requirements of game birds on a given farm and will use this in arriving at his recommendations for development practices. He may find that woody or herbaceous cover exists in sufficient quantities to preclude the planting of any additional cover of this type.

Sacramento Experimental Area, near Wilcox, Neb., has paid good dividends in learning better habitat planting methods.

A typical planting containing Russian Olive, Multiflora Rose and Cedar, borders this Nebraska farm pond.

On the other hand, the existing cover may not have the proper dispersal and he will recommend small plantings of the type to provide sanctuary areas, nesting cover, feeding areas or travel lanes. He may also recommend the establishment of multiflora rose fences which can be used by wildlife as travel lanes and by the landowner as fences which divide cropland and pasture or as farm boundaries.

Since nesting cover is becoming something of a problem, the Land Manager's recommendations may include the seeding of small or odd areas to sweet clover or alfalfa. Wherever such seedings are recommended, the necessary seed will be supplied by the Game Commission until the yearly allotment has been exhausted.

The Land Manager may conclude that some odd areas, because of erosion problems, should be allowed to produce a crop of seeds providing, of course, no noxious weeds are present. The Game Commission will supply all planting stock free of charge and in many instances will do the planting. Game Commission personnel can plant only so much during the short planting season here in Nebraska, so those sites planted will be allotted on a "first come-first served" basis.

The Land Manager has been stationed at the designated headquarters throughout the state and is there for the sole purpose of assisting landowners who are interested in restoring or creating habitat beneficial to wildlife. You are encouraged to take advantage of this man's services whenever you have a habitat problem or whenever you feel that he could be of some help as an advisor along this general line. He is there to assist you in making Nebraska a more productive state—a better state in which to live.

FALL ISSUE 5

MEET YOUR New District Managers

With the opening of the District Headquarters, the reorganization plan of the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission is becoming a reality. Each of the new offices has been established and personnel to staff these offices have moved into their respective communities.

Outdoor Nebraska deems it proper to introduce each of the District personnel for two reasons. First, in keep-ing with the grassroots philosophy behind the new reorganization plan, the public should be introduced to these men in order to start a basis for the cooperation necessary to make the plan succeed.

The second reason is to offer the calling card of the District personnel to the people in their Districts in a gesture of good neighborliness.

Each of these men have been assigned to their respective jobs to work on Game Commission problems on a local level. By living in the work area, these men will be better able to gather information, make recommendations and carry out administrative orders concerning wildlife problems of Nebraska.

Land ManagersThe Land Managers have the important assignment of being the liason man between the land owner and the Game Commission. Their consideration will be to balance out good farm economy with wildlife improvement work. Their services will be available to any land owner in their District that would like to improve the wildlife situation on his land.

These men will be primarily occupied with making habitat improvement plans for land owners that show an interest in bettering the wildlife situation. (See the story HABITAT IMPROVEMENT, Page 3.) The Land Managers are in the Land Management Division: Jack Strain, Supervisor.

William Bailey District III, Norfolk

Clarence Newton District V, Lincoln

Kenneth Johnson District II, Bassett

Charles Bohart District IV, North Platte

Fisheries

Managers

Fisheries

Managers

The beginning job assignment for Fisheries Managers will be stream and lake surveys on the waters in their Districts. Stream and lake surveys entail a multitude of things such as size, depth, chemical composition and average temperatures of the water. After these are known, the problem of the fish population can be undertaken.

How old are the various groups of fish in the whole population? What kind of fish are there? What kind and how much food is there for the fish? Is there natural reproduction? Are the fish stunted in their growth rate?

These and many other questions are present for the Fisheries Managers to seek the answers. Here we see the need for investigation into a complex problem to glean enough facts for the Game Commission administrators to use in formulating management policies.

John Heaton District I, Alliance

Bruce McCarraher District II, Basselt

Elmer Carlson District III, Norfolk

Orty Orr District IV, North Platte

Walter Kiener District V, Lincoln

Game

Managers

Game

Managers

The problem of the Game Managers will be of the same general pattern as the Fisheries Managers, but will of course concern game. Development of more accurate censusing methods will be an important job for these men. An accurate inventory is a prime requisite for good management of any game animal. The Game Manager in District I will be primarily concerned with deer and antelope studies. In District II, waterfowl and grouse will occupy most of the study work. In the three remaining Districts, III, IV and V, the Managers will concentrate on the investigation and management of pheasants. Needless to say, the Game Managers will be responsible for all kinds of game in their respective Districts, but the distribution of the different game animals makes the above pattern mandatory. The Game Managers are in the Game Management Division: Lloyd Vance, Supervisor.

Stan Smith District I, Alliance

Harvey Miller District II, Basselt

Raymond Linder District III, Norfolk

Dan Heyl District IV, North Platte

George Schildman District V, Lincoln

Chiel

Conservation

Officers

Chiel

Conservation

Officers

The Chief Conservation Officers will coordinate the activities of the other Officers in their respective districts. All law enforcement problems will be assigned to them unless of a specialized nature or of an extreme local nature where it could be best handled by a local Officer. It is the thought of the Commission that localizing the immediate supervision of the Officers in the field will benefit the Law Enforcement Division by providing a more efficient operation. It is also believed that the job of the individual Officers will be made easier as the work becomes better coordinated. The District Headquarters will also provide a place to store specialized equipment to be readily available when needed. These Officers are assigned to the Law Enforcement Division: William Cunningham, Supervisor.

Edward Bosak District L Alliance

Allen McCarroll District II, Bassett

Robert Benson District III, Norfolk

Sam Grasmick District IV, North Platte

Operations

Managers

Operations

Managers

The Operation Managers will be in charge of the basic work crew in their respective Districts. They will be charged with taking care of the habitat planting during the spring planting season. (See the story HABITAT IMPROVEMENT, Page 3.)

After the planting season, when the heavy use period on Commission facilities begins, much of their time will be spent on maintenance clean-up work. Following this period, the Operation Managers will take their crews on maintenance and repair jobs in their Districts. They will provide extra labor for the use of the Game and Fisheries Managers when extra help is needed on study projects. The Operations Managers are assigned to the Construction and Engineering Division: Gene Baker, Supervisor.

Lem Hewitt District I, Alliance

Dallas Johnson District II, Basselt

Frank Sleight District IV, North Platte

Richard Wickert District III, Norfolk

Ira Glasser District V, Lincoln

Nature's Ability Of REPLENISHING WILDLIFE POPULATIONS

by George ShildmanIT had drizzled off and on all night and the cooler temperature was a welcome relief from heat of the past early August days. It was a wonderful rain—Slow and easy—and every bit of it soaked into the ground. The vegetation was drooping with the weight of moisture on the leaves. Jim Grey had promised Bill Adams, his neighbor a half mile to the west, that he would help him do some work on his tractor. Jim called Bill to see if he didn't think this would be a good time to work on that ailing tractor, and Bill agreed.

When Jim drove up, Bill was standing with one foot on the gate watching something in the hog lot. A hen and seven young pheasants were standing in the bare lot just outside the wet grass. Bill commented, "The first young I have seen in a couple of weeks." Jim chimed in with, "I haven't seen many birds for the last two or three weeks either, but I did see two broods in the road while driving over here." Bill guessed that "maybe the wet vegetation is the reason for their sudden appearance, and probably during the hot, dry spell they were staying in the cover out of sight."

They watched a little bit and the hen watched them while the chicks pecked here and there at something on the grourid. They agreed that the rearing of young birds was one of nature's more interesting phases to watch. But they disagreed when Jim said, "They are so small it must be her second brood." Bill promptly informed him that pheasants only have one brood a year. Jim came right back with, "How do you account then for the fact that the other young birds I saw were one-half to two-thirds grown and these little fellows can't be more than a couple of weeks old?"

With a pleased look on his face Bill answered that question: "It takes about two weeks for a hen to lay her clutch of ten or twelve eggs and another three weeks to incubate them. If she stays with the young until they are ten weeks old or older, she has consumed more than three months of the summer with one brood. If she started laying in early May (and most hens don"t start before the middle of May) the middle of August hardly leaves time enough to start another nest. A hen will renest if her first nest is destroyed and even a third attempt if necessary. Of course this renesting is what accounts for these late birds."

Jim asked Bill how he knew so much about this. He conceded that he had thought the way Jim did until his boy explained it to him following his return from a 4-H camp meeting last spring.

While we let Bill and Jim get to work on that tractor—it might be dry enough to get into the fields by tomorrow—let's look at some of the reproductive powers mother nature has given to some of our wildlife species.

In general, those species that have a short life expectancy produce many more offspring than those with a long life expectancy. For example, the white has a very short life span (scarcely a year for 80% of the birds) and averages about 14 eggs, while a deer, that might expect to live 10 years or more, produces but one or two young a year.

Also, species that are staple food for predators, as a rule, have a much higher reproductive rate than do the predators that prey upon them. For example, the meadow mouse may produce four to six litters a year, averaging six or seven young per litter, and the cottontail may have three or four litters of four young, compared to the coyote's one litter of five, or the marsh hawk's single brood of three or four.

Another characteristic of reproduction is the inverse ratio of production rates to breeding populations. This is probably more of a function of survival of the young than it is a function of greater numbers of young produced by each female. However, both functions do operate. If some factor or factors should cut the breeding population below what the land could expect to support, then a greater percentage of the females not only produce young, but a greater percentage of the young survive to maturity. The opposite occurs if the breeding population is larger than the land can support.

Soil fertility and quality and quantity of food also affects reproduction. Where quantity and quality of food is excellent, as it is on most of Nebraska's deer range, twin fawns are common. But on some of the deer ranges in some parts of the country where there is insufficient and poor quality food, twin fawnings are rare and some does even fail to bear any young. Similarly, fertile soils will support more game than poor soils.

Reproduction and survival are two separate phases of productivity. These are important in determining our harvestable surplus of game come the hunting seasons.

The reproductive potential of all of our upland game birds in Nebraska is very high. For instance, a single pair of quail could result in a population of over a thousand birds in 3 years if all the birds survived and half were females and each female produced an average of 14 young. Likewise, a pair of pheasants would result in 432 pheasants. Or if we started with a quarter of a million hens in the state in a given spring, under these same conditions, 3 years later we would have 324 million pheasants. Where would we put them?

Let's get back to reality—all the hens don't nest, all the nests aren't successful, and all the young that hatch don't survive until fall, let alone three years. Actually about 70% of the young pheasants that survive until fall won't live to see two falls, and 80% or more of the quail that survive until November won't be alive a year later. Although these birds have great reproductive powers, mortality is also very great.

We have mentioned several characteristics of reproduction and some facts about survival and the resulting population. Reproductive powers being as great as they are, mortality would appear to be the thing we have to lick to have greater populations. But we must remember that mortality is largely controlled by the life expectancy of an animal and the ability of the land to support more of a given species. As the habitat improves for an animal mortality decreases.

FALL ISSUE 11

it takes penetration and pattern density FOR MORE CLEAN KILLS

by Loron BunneyTHERE is nothing more disheartening than to pull down on a pheasant or duck, pull the trigger and watch the bird falter in the air for a moment and then keep on going. A cripple, flying off in the distance—you know he will drop sooner or later, but most of the time you can count these birds as lost.

You know that you hit the bird, but one of two things is wrong. You either didn't hit it with enough pellets or the pellets didn't hit hard enough to penetrate. A killing load for small game birds depends on these two factors. One alone is useless; it takes the combination of penetration and density of pattern to do the job.

As both large and small shot leave the gun at the same muzzle velocity, the ability to penetrate is about the same for all sizes of shot at the muzzle of your gun. Small shot lose their velocity much faster than the large shot, which means the ability of penetration is also lost much sooner than with large shot.

Small and large shot both start to spread the instant they leave the muzzle of the gun and by the time they travel 50 yards, even in a full choke barrel, the diameter of the shot circle will be 4 to 5 feet. Obviously, the smaller size shot will have more pellets to cover this area and the larqer size shot, such as 2's and 4's, will have less coverage.

According to some authorities, it takes five pellets to make a clean kill on the average shot at a pheasant or a small duck. Number 8 shot at 50 yards would probably hit a bird with more shot than five pellets, but the penetration would be sadly lacking. Nuber 2 shot would have enough velocity to go completely through most game birds at this distance. But, owing to the small number of pellets in the load, you probably would be very lucky to place one pellet in the bird. You can see that neither of these two shot sizes would make a clean kill at this range. However, at 35 yards, either size would make a clean kill.

The accompanying graph is one person's idea of what to expect from several shot sizes when used in a full choke barrel on pheasants and small ducks. Any yardage column where a complete diamond is shown for different size shot is considered within range for consistent clean kills. Beyond this point either the pattern or penetration is going to fizzle out and you are going to get more crippled and lost birds.

12 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Why Have Big Game Checking Stations?

by Stan SmithAGAIN this year, as in the past, your Game Commission will have big game checking stations located in the deer hunting areas. Each of the successful deer hunters will bring his, or in some cases her, prize into one of these stations, where it will be weighed and have its teeth examined. They will also answer some questions as to where the deer was shot. Finally, a seal will be placed on the deer and the hunter will be on his way once again.

' As he leaves the checking station, however, he may wonder what the Game Commission intends to do with the information collected at the checking station. Why should the deer be weighed? Why did they look at its teeth? Why did they ask the question as to where it was shot? And above all, what has this got to do with the deer season?

You, the hunter, have an explanation coming and we will now attempt to furnish it. We want information that cannot be obtained in any other way except by handling the deer you kill. Let's get down to cases. We need to know several things about the deer herd in order to properly manage it for a continued harvest.

First of all, we need to know whether the deer are healthy. Can we look at a dead deer and determine its health? Indirectly—yes! And here's how. By summarizing checking station data gathered over a period of years, we have a pretty good idea of how much a healthy deer should weigh. But it's not the individual weight we want, it's the average of all the deer within a single sex and age group. That finally pins our information down so that it is useful, for the weight alone is valueless unless it is related to sex and age.

Now we know that a 1V2-year-old buck mule deer from a healthy herd will weigh between 105 and 110 pounds and a 2 1/2-year-old will weigh about 125 pounds. Other average weights have been worked out for age and sex groups. Of course, there are always exceptions to these average weights, but generally the healthy deer will fall in this pattern.

That should explain why the weight of your deer is needed. But here is a problem that until recently had game technicians stumped. How can you tell the age of a deer?

You and I have a birth certificate which tells how old we are, and so does the deer! All we have to do is learn how to read it. Game technicians have learned to tell the age of a deer by the condition of its teeth much the same as a horse's age is told by the condition of its teeth.

We know that almost all of our deer are born early in the summer, about the first of June. When the hunting season comes around the fawn will be about 6 months old, and it won't have all of its teeth yet. He will have but four of six pairs of molars and premolar teeth in his lower jaw. The premolar teeth, called "milk" teeth, are the first teeth to appear and are only temporary.

When the second hunting season rolls around our deer will be 1 1/2 years old, and it will have its full set of teeth, including its milk teeth. When he reaches the age of 2 1/2 years, however, the milk teeth have been replaced, and from here on the deer's age will be determined by the amount of wear on the teeth. It takes time to learn this system, but once learned it is reliable.

Now we have the weight and age of your deer. But suppose we find out that some of the deer coming through the station are consistently low in weight for their sex and age class. This could mean that the deer from some area are not getting enough to eat, possibly because the herd in that area is too large for the carrying capacity. This points to the next bit of information needed. Unless we know where the unthrifty deer come from, we may not be able to help them. For this reason you will be asked to tell us where you killed your deer. In this way we can locate our trouble spots and initiate management measures to alleviate the trouble. Likewise we can determine whether or not the deer from other areas are in good shape.

Technicians sometimes want other information from you, the hunter, when you bring your deer through the checking station, but only as a check on information obtained from the field. Technicians will be working year 'round with deer. They will be trying to determine population trends, size of the fawn crop, natural mortality factors, food habits, etc. It's a full-time job!

Proper management has been mentioned several times here without any explanation of what we mean by it. This term can be defined in several ways, but essentially, we mean maintaining a huntable population of deer and not allowing them to increase to the point where they will become an economic threat to the Nebraska farmer and rancher. In other words, we want some deer, but we can have too many.

Biologists are kept busy trying to find out how many deer an area can support and also how many deer are in that area. If there is a surplus of deer over the carrying capacity of the area, they must be removed. If there are very few deer in an area that can support much larger herds, then the area should be closed to hunting until the population builds up. This building up of populations to the carrying capacity of the land, as a general rule, takes only a few seasons on good deer ranges. This, then, is what we mean by proper management.

The hunter is doing two things when he brings his deer to the checking station. He is removing a "surplus" deer and he is helping the state Game Commission technicians obtain information needed for keeping Nebraska's deer herds on a sustained vield basis.

FALL ISSUE 13

WILDLIFE in one reel

1954 Nebraska Hunting Seasons

(The bag and possession limit on ducks of 5 and 10 may include one wood duck and one hooded merganser.) fMergansers (fish ducks) are to be included in the above bag and possession limits.) One-half hour before sunrise to sunset, except on opening day when hunting commences at noon.

GEESE OCT. 8-DEC. 6 ENTIRE STATE 5 5(Daily bag and possession limit on geese is 5, includinq in such limit not more than (a) 2 Canada geese or its subspecies, or (b) white-fronted geese, or (c) 1 Canada goose or its subspecies and 1 white-fronted goose One-half hour before sunrise to sunset, except on opening day when hunting commences at noon.

COOT (Mudhen) OCT. 8-DEC. 6 ENTIRE STATE 10One-half hour before sunrise to sunset, except on opening day when hunting commences

COCK PHEASANTS OCT. 16-OCT. 25 RESTRICTED AREA 2 2(All pheasants taken must retain sex identification. Either head or feet must be left on the bird.) (All counties open to pheasant hunting except Antelope, Gage, Jefferson, Johnson, Madison, Nemaha, Pawnee, Pierce, Richardson and Thayer counties; and also all Federal and State sanctuaries and refuges. Areas posted with signs reading—"Hunting Prohibited! Pheasant Restocking Area—This area is closed to*all hunting during the pheasant season by the authority of the Nebraska Game Commission." One-half hour before sunrise to sunset.

QUAIL OCT. 30-NOV. 25 RESTRICTED AREA(Following counties are open: Adams, Buffalo, Butler, Cass, Clay, Dawson, Douglas, Fillmore, Franklin, Frontier, Furnas, Gage, Gosper, Hall, Hamilton, Harlan, Hayes, Hitchcock, Howard, Jefferson, Johnson, Kearney, Lancaster, Lincoln, Merrick, Nance, Nemaha, Nuckolls, Otoe, Pawnee, Phelps, Polk, Red Willow, Richardson, Saline, Sarpy, Saunders, Seward, Thayer, Webster ond York counties and that portion of the following counties located south of U. S. Highway No. 30: Colfax, Dodge, Platte, and Washington, except for Federal and State sanctuaries and refuges in these areas. (All other counties are closed.) One-half hour before sunrise to one hour before sunset.

RABBITS APR. 1-JAN. 31 ENTIRE STATEOne-half hour before sunrise to sunset.

SQUIRRELS OCT. 1-DEC. 31 ENTIRE STATEOne-half hour before sunrise to sunset.

RACCOON AUG. 1-MAR. 31 ENTIRE STATE NO LIMIT_______AH hours.

OPOSSUM AUG. 1-MAR. 31 ENTIRE STATE NO LIMITAll hours.

16 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA SPECIES OPEN SEASON AREA OPEN

LIMIT BAG POSS

DEER (Area 1)

DEC. 4- 8 (1500 Permits)

Banner, Cheyenne, Garden, Kimball, Morrill,

and Scotts Bluff counties. One-half hour

before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset.

DEER (Area 2)

DEC. 4- 8 0 500 permits)

Box Butte, Dawes, Sheridan, and Sioux

counties. One-half hour before sunrise to

one-half hour after sunset.

* *

1

* *

1

DEER (Area 3)

DEC. 11-15 ( 500 permits)

Brown, Cherry Keya Paha, and Rock counties.

One-half hour before sunrise to one-half

hour after sunset.

1

* * *

1

DEER (Area 4)

DEC. 11-15 ( 500 permits) Boyd, Cedar, Dakota, Dixon, Holt and

Knox counties. One-half hour before sunrise

to one-half hour after sunset.

1

* * *

1

ANTELOPE

SEPT. 11-13 ( 5°° permits)

Only those areas of Garden, Morrill, and

Scotts Bluff counties north of the North

Platte river and those parts of Sheridan,

Box butte, Dawes and Sioux counties south

and west of State Highway No 2. One-half

hour before sunrise to one-half hour

after sunset.

NOTES

* *

'Where entire counties are open, these do not include Federal or State sanctuaries or refuge areas.

Areas I and II—Antlerless deer may be taken only on December 8 On all other days of the open

season, antlered deer only with a fork on ai least one antler.

'"Areas III and IV—Antlered deer only with a fork on at least one antler.

SPECIES OPEN SEASON AREA OPEN

LIMIT BAG POSS

DEER (Area 1)

DEC. 4- 8 (1500 Permits)

Banner, Cheyenne, Garden, Kimball, Morrill,

and Scotts Bluff counties. One-half hour

before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset.

DEER (Area 2)

DEC. 4- 8 0 500 permits)

Box Butte, Dawes, Sheridan, and Sioux

counties. One-half hour before sunrise to

one-half hour after sunset.

* *

1

* *

1

DEER (Area 3)

DEC. 11-15 ( 500 permits)

Brown, Cherry Keya Paha, and Rock counties.

One-half hour before sunrise to one-half

hour after sunset.

1

* * *

1

DEER (Area 4)

DEC. 11-15 ( 500 permits) Boyd, Cedar, Dakota, Dixon, Holt and

Knox counties. One-half hour before sunrise

to one-half hour after sunset.

1

* * *

1

ANTELOPE

SEPT. 11-13 ( 5°° permits)

Only those areas of Garden, Morrill, and

Scotts Bluff counties north of the North

Platte river and those parts of Sheridan,

Box butte, Dawes and Sioux counties south

and west of State Highway No 2. One-half

hour before sunrise to one-half hour

after sunset.

NOTES

* *

'Where entire counties are open, these do not include Federal or State sanctuaries or refuge areas.

Areas I and II—Antlerless deer may be taken only on December 8 On all other days of the open

season, antlered deer only with a fork on ai least one antler.

'"Areas III and IV—Antlered deer only with a fork on at least one antler.

NEBRASKA BOY SCOUTS Conservation Good Turn

Throughout Nebraska, Boy Scouts have been participating in a conservation movement at the request of President Eisenhower. This program, called Conservation Good Turn, is an effort to familiarize Scouts with the fundamentals of conservation of our natural resources. Various projects and field trips give the Scouts first hand information on conservation of the Nation's soil, waters, forests, minerals, grasslands and wildlife.

The accompanying pictures illustrate a few of the many projects in which Nebraska Scouts are participating. Outdoor Nebraska offers a hearty "well done" to all Scouts and their leaders.

Racoon tracks hold the attention of this group of Scouts on a conservation field trip.

Wood duck nesting boxes are made as conservation projects by these Nebraska Scouts.

Habitat plantings are an important phase of the Conservation Good Turn program.

Some of the fundamentals of farm pond management are being explained by a conserva tion technician to this group of Scouts.

Soil and water conservation is learned at the site of actual projects in the field.

Learning that wildlife is a crop of the farm is the lesson these Scouts are receiving.

Spotting and learning to identify waterfowl keeps these future duck hunters busy.

These Boy Scouts are studying a Tiger salamander, a Leopard frog and a crappie found on their field trip.

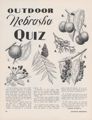

Outdoor Nebraska Quiz

All of the plants in this issue's Outdoor Quiz are important to wildlife either as food sources or as cover and in some cases both. As each of these plants have their own important place in the Nebraska wildlife scene, you probably have seen all of them during your trips afield and may be able to identify some of them.

A. The brilliant colored leaves of this plant are a gaudy part of the autumn scene in Nebraska's quail country. Its main function, as far as wildlife is concerned, is to provide shelter. No

B. Thickets of this plant, often sprayed in the mistaken idea that they grow up into power and telephone lines, provide both cover and food for wildlife. No

C. This plant, not a native of Nebraska, is easily identified by its large green fruits and was planted for fence rows by many early settlers No

D. A member of the conifer or evergreen family, this plant offers both food and shelter to many Nebraskagame birds and animals. It is an important plan in the habitat planting made by the Game Commission. No

E. A favorite food and cover plant for game birds, this plan also produces a dark purple fruit used by humans for making wine, jam and jelly.No

F. This thorny plant, an imported variety, is one of the main tools used in habitat plantings, living fences and soil conservation practices. No.Answers on page 25

20 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

If You Want Sport and Fun HUNT SMALL GAME ANIMALS

by Wally GreenIF you are a typical Nebraska hunter, it has been a long time since you drew a bead on the head of a fox squirrel or swung your gun barrel along the path taken by a cottontail rabbit as it bounces for cover. Just why many of us forsake the pleasures of youthful hunting, such as these, is a mute question. Certainly the first hunting that many of us ever did, was on one or both of these fine small game animals.

Perhaps, as we grew older and started hunting the more glamorous and exciting game such as pheasants, ducks and quail, we were quick to forget the simple pleasures and thrills to be derived from a Saturday afternoon spent hunting rabbits or a morning spent stalking squirrels. Or, perhaps, as we took on the responsibilities of adulthood, we found that we had precious little time to spend in the field and therefore concentrated our time on game birds.

Another reason could be that we have been spoiled by the huge populations of pheasants that existed during the early forties, when there was much idle farm land to support them. Many of us adults look down our noses, while bragging about the "double on mallards" or "bag of pheasants" we took and consider hunting for rabbits and squirrels "just a kid's sport." True, there are some Nebraska hunters that consider these two game animals as challenge enough for anyone's shooting ability.

Take the cottontail rabbit, for instance—he actually is the number one game animal in the United States. More shells are shot up each year by hunters gunning for cottontails than any other single game animal, or bird, for that matter. Here in Nebraska, the cottontail rabbit is surely the most popular game mammal sought by hunters, but then most of us are bird hunters.

One of the most exciting and enjoyable methods of hunting rabbits is to have good dogs working for you. There are the specialized rabbit dogs such as the beagle and bassett hounds that were bred for generations to take up the trail of the cottontail. Also, many other breeds, and even some without a particular breed, will make satisfactory rabbit dogs. We have all heard of the fox terrier that is the "best dog-gone rabbit dog in the county" and some of us have even hunted behind one.

No matter what kind of dog you are hunting rabbits with, you can't help but thrill with expectancy when a streak of gray bounces out of a brushy swale and takes off across the countryside. Many rabbit hunters will tell you that, if you don't shoot the rabbit when the dog first flushes it, the two will run in a big circle and soon you will hear them coming from the opposite direction, headed for the spot where they began. This will happen sometimes when you have a very slow working dog, but if he is a fast-traveling animal, the rabbit will "hole up" in the first spot he can find.

If you are not fortunate enough to have a rabbit dog or any kind of dog, you can still get a lot of rabbit hunting. You would find that it would help if you could think like a rabbit in order to locate some of its favorite hiding spots.

Farms, with their mixture of crops and brushy field borders, are just the ticket for the welfare of the cottontail rabbit in Nebraska. Food and cover, the two factors needed by all wildlife, are usually plentiful unless the land is being farmed too intensively. True, the cottontail has its own ideas about what kind of cover is best, but the main thing they seem to thrive on is a mixture of different types of cover interspersed through a variety of farm crops.

You can find them in the wild grass and weeds of the fence rows, waterways and field borders. Don't overlook the abandoned farmstead and school yards with their tangle of weeds and grass, either. Old hedge rows and brush piles often produce good rabbit hunting. Any type of vegetative cover, large enough to conceal a rabbit, can have a rabbit in it, is a good rule to follow when hunting without a dog. Walk slowly and work the cover over thoroughly.

Picked corn fields are sure producers unless the weather is cold enough to prevent cottontails from being out. You don't have to work the whole field, as they are too smart to venture out into the center, as a general rule. By working the edges, where the cover is, not more than 30 feet into the field, you will get a shot at the majority of rabbits in the whole field. Most of the daylight hours of the cottontail are spent sitting in a patch of cover, and

he will venture out to eat, only occasionally. He has too many natural enemies to get very far from cover.

he will venture out to eat, only occasionally. He has too many natural enemies to get very far from cover.

His natural enemies during the daylight hours, such as the marsh, redtailed, red-shouldered, broad-winged and Swainson's hawks make him a cautious character, to say the least. Other enemies are the fox, coyote and the domestic dog. The biggest threat the rabbit contends with at night, his main feeding period, is the silent winged owl. The feral or wild domestic cat is suspected of being a decimator of rabbits during their night prowlings.

The list of these natural enemies of the cottontail can give us a clue as to when to hunt, if we take a look also at how the rabbit population fluctuates. Towards the end of the summer, after all the season's litters are born and are growing up, the rabbit population is at its highest. A drive down a country road on a late summer or early fall evening will give you an idea of how populous they are at this time. Game technicians have found that as high as 75 per cent of these rabbits will be gone by the first of January! This is the case, even if there is no hunting pressure. All the reasons for this decrease in numbers are not known, but predation does play a big factor in the decrease.

As the fall season progresses, much of the cover for the cottontail is disappearing and no longer offers protection from predators. Another factor that reduces the population is natural death from old age, as the cottontail, like many other game animals, is shortlived.

If 75 per cent of the rabbits are dead by the end of three fall months, the death rate must be high. The answer to better harvesting of this wildlife resource is quite apparent. Start to hunt them before much of this mortality takes place. Begin your rabbit hunting early in the season.

"Wait a minute," you may object. "What about that rabbit disease called tuleremia?" That is a fair question, and you certainly deserve an answer.

We will have to go back to the late thirties and early forties to give a satisfactory answer. Those were the days when there was a scare about this disease. Public health and game commission personnel, through the midwest, were alarmed by the numerous cases of tuleremia and could trace some cases to people who had dressed out infected rabbits. They found that the disease was contracted by handling carcasses of infected animals but that cooking destroyed the infectious disease.

They believed all infected rabbits died by the second or third heavy frost and this was all they needed to start a strong campaign to educate the public to wait until late in the year before hunting rabbits.

Today, it is believed that tuleremia is rare and that reasonable sanitation precautions taken by the hunter when dressing out game will eliminate most of the danger of contracting this disease. Cleanliness is the key to these precautions. After cleaning the game, wash your hands very thoroughly with soap and water and you will have eliminated most of the danger. One word of caution: If you have any open cuts or scratches on your hands, don't dress out any game.

You can see that the main objection to early season hunting can be eliminated, so if you want to make the best of a fine game resource, if you want to practice common sense and good conservation at the same time, you will start your cottontail hunting as early as possible, before natural mortality cheats you out of many of them.

Generally speaking, there is not too much to be done for increasing the rabbit population; however, if you do want to attract more rabbits on your land, there are a few simple things to do. A brush pile left here and there, an extra foot or so left in grass and weeds along a fence row or even a regular habitat planting made by the Game Commission will help attract and hold more rabbits on your land. Give them a place to live and the cottontail's natural reproductive powers will take care of the rest, just as is the case with most wildlife.

Squirrels in Nebraska are, like the cottontail rabbit, a crop of the farm land. Most of them live on small isolated woodlots adjoining farmland.

Of course, in some areas in the eastern part of the state, such as the Missouri River bottoms and bluffs, there are extensive areas of hardwood timber that are the top Nebraska squirrel range. Even these forest areas, with their hardwood trees like oak, hickory, beech, maple and others, are interspersed with farm land. Many of us think of the squirrel as an animal of the heavy forest, but this is not the case. Even in the early years of this country, the fox squirrel was an animal of the edges of the heavy forests, with the largest populations being found in the transition zone between the heavy eastern forests and the prairie regions of the West.

As settlement caused the breaking up of the eastern forest for agriculture, the fox squirrel population grew by leaps and bounds. Here in Nebraska, the smaller isolated stands of trees, usually found near a stream course, were made up of willows, elms and cottonwood. There was only one thing lacking before these stands could support good squirrel populations and that was food. There were even good den trees for raising young and protection from winter blasts, as the cottonwood trees rot in the center as they get older. Food was the limiting factor, and soon this was to change.

As soon as the early Nebraska settlers began putting in their first corn crops, the fox squirrel started to expand westward from his former limited range. Undoubtedly many of our present-day squirrels would perish if it weren't possible for them to live off farm products. The majority of the smaller stands of trees, where squirrel are now living in Nebraska, do not have enough natural food to support the squirrels living in them.

Natural foods of the squirrel are corn and the mast from oak, hickory, black walnut, butternut, pines and sometimes buckeye. These foods are gathered and stored for use when the nut supply is used up. Emergency foods include seeds and buds of maple, elm, oak, seeds of poplar, catkins of willow and the fruit of osage orange.

Besides their affinity for farmland, squirrels also have another characteristic that is similar to the cottontail rabbit. That is, the use of dogs for hunting is one of the more popular and exciting methods, especially in the eastern timbered areas of the state. No particular breeds have been established for squirrel hunting, so any dog that will pick up a scent and will tree a bushy tail makes a squirrel dog.

Whether you are hunting with or without a dog, you will probably want to do your squirrel hunting early in the morning. Besides this time being the period of activity for any self-respecting squirrel, you will find it is much quieter walking through the leaves, as they are generally damp or wet.

The previous remark about quiet walking is important. Sound is the warning signal for squirrels. If you can move through the timber quietly, you will have some good shots; if not, you will find the going pretty rough, with or without a dog.

Besides locating and treeing the

squirrel, a good dog will help you get

a telling shot. Unless the squirrel has

gone up a den tree, he will keep on

the opposite side of the tree or move

from limb to limb so you can't get

a shot at him. With a dog at the foot

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of the tree to keep him occupied, you

can usually move into position on the

other side to draw a bead.

of the tree to keep him occupied, you

can usually move into position on the

other side to draw a bead.

You will find that you are usually drawing a bead on a very small portion of the squirrel, as they are notorious for their ability to hide. It takes a sharp eye to locate a squirrel head up among the branches of an oak with its brown leaves fluttering in an autumn breeze. It takes a steady hand and a sharper eye to hit that head. Whether you are using a shotgun or a .22 rifle, there is a challenge.

Probably the best way to hunt squirrels without a dog is to slip quietly into a spot that will give you a good view of the surrounding trees. Just sit patiently and within 10 or 15 minutes you will get some shooting, unless that particular spot is hunted heavily. Squirrels, for all their alertness, are curious fellows and will be out to see where you are after the first alarm.

If this is the method of squirrel hunting that you will be doing, here is an important thing to remember. Don't run over and pick up your first trophy. Mark the spot and let it lie until you are ready to leave. If you don't, all the squirrels in that area will be spooked after the first or second shot.

Due to the type of squirrel habitat in many areas of Nebraska, isolated woodlots and strips of timber along streams, there is one precaution that you should follow to insure hunting each year. If you clean out a population in one of these isolated spots, it may be two or three years before squirrels begin moving back in. Conservation in this case is wise harvesting, leaving enough squirrels for breeding stock. This will only hold true in the very small wooded areas that are cut off from other timber.

In the more extensive timber, you will probably get your limit before you would begin to endanger any breeding stock. Also, in the more extensive areas, it is practically impossible to clean out the population. As the hunting gets too heavy, the return to the hunter for time spent gets too low. Hunters will hunt at more productive locations where the squirrels are more numerous and not as "wild."

Whether it is rabbits or squirrels you are gunning for, the handling you give it in the field means the difference between excellent eating and just fair eating. Field dress your game as soon as possible by cleaning out the intestinal cavity and wiping the blood out. Give it a chance to lose body heat and cool off. Don't pile it in a game bag, in a hunting jacket or heap it in a pile in the car. Much game could be saved from spoiling or losing its quality by following these simple precautions.

Whether it is your first hunting trip this year, in twenty years or in your lifetime, for either rabbits or squirrels, you will have much to look forward to if hunting these two fine Nebraska game animals.

NEWS OF WILDLIFE CLUBS

"OUTDOOR NEBRASKA" is proud of the fine cooperation of the constructive wildlife clubs in Nebraska and provides this section for any club activities, pictures or reports, as space permits.

St. Paul Gun Club The club has leased Svoboda lake, dredged it deeper, opened a drive with parking facilities and contacted the Game Commission for stocking. They are planning shoots on Oct. 3, Nov. 11 and Nov. 21. Club membership: 150.

Fremont Izaak Walton Club This club held open house for all Nebraska "Ikes" on Sept. 26. They also voted to pay $35.00 toward expenses for a teacher to attend the summer school Conservation workshop course in the suinmer of 1955. The regular meeting nights are the first Monday of every month. Their annual gun safety program is planned for early October, this year. Club membership: 293.

Morrill County Wildlife Club The club has established a plan for extensive fish habitat improvement of the new state owned lakes near Bridgeport. They report good results with their 500 bird booster unit and made releases during the first week in September. Meeting night is the third Monday each month. Club membership: 96.

Ravenna Izaak Walton Club This club has been putting on a big campaign each year to get more farmers to use flushing bars during their mowing operations. They have even received a request for their club-designed flushing bar from the Netherlands Institute of Biology in Netherlands. They also have published an attractive brochure to explain their activities in pheasant improvement work. They meet the last Thursday of each month. Club membership: 128.

Pawnee County Sportsmen's Club This is the first year for this club and they are interested in having a state owned lake in their part of the state. They are working with the private pond owners in a program designed to provide more fishing for everyone. Club membership: 158.

Golden Retriever Club This club has or will hold five sanctioned field trials this year. Some of these trials are open to all breeds of retrievers. Plans next year include a licensed field trial in the fall. Club membership: 23.

West Nebraska Sportsmen's Assn. Booster unit pens are empty now and repair and improvement is being planned. They are having a big membership drive this fall. Fall meeting nights are the first of each month. Club membership: 329.

Norfolk Izaak Walton Club Regular meeting night for this club is the third Thursday of each month and Family Night is on the first Monday of each month. Club membership: 190.

Four Corners Rod and Gun Club This club has a heavy schedule of events coming up for the fall. Blue rock shoot, Oct. 10; Movies, Oct. 15; blue rock shoot and box supper, Oct. 24; blue rock shoot, Nov. 7; Championship shoot, Nov. 11; Movies, Nov. 12; and a blue rock shoot. Nov. 21. Practice shooting will be held Oct. 3, 17, and 31, Nov. 14 and 18.

Chimney Rock Gun and Rod Club This club wishes to thank Kurt Merrchew for allowing the club members to take Bayard children on his lake lor the "Jesse Fowler Day'' fishing excursion. The club has been active with booster units for pheasants and stocking farm ponds for kids' fishing.

FOCUS THE PICTURE

Following are characteristics of a non-game bird inhabiting Nebraska. How many of the characteristics must you read before you can bring the picture into focus?

1. This bird is a hunter, but he isn't a hawk, falcon or owl.

2. He can usually be seen perched on a post, fence wire or telephone wire while he scans the country side for prey.

3. This bird is fairly common in all parts of Nebraska. He has a close relative that is found in the Northern part of the continent and wanders South to Nebraska, occasionally.

4. It is the same size as a robin.

5. His color is gray over-all, with clear white below and a black bill. He has a band along the side of the eyes, black tipped wings and tail.

6. Food for this bird consists of many insects like grasshoppers and crickets, but snakes, lizards, frogs, mice and some birds are taken.

7. He is partially migratory and usually travels South in the winter, although some stay in Nebraska all year round.

8. He generally flys close to the ground, using a rapid wingbeat followed by a short glide.

9. In flight, a white patch on the back of each wing flashes with each wing beat.

10- You might know this bird as the "Butcher Bird," because of its habit of tearing up larger prey by impaling it on a thorn or fence barb and pulling it to pieces.

Answers on page 25

FALL ISSUE 23

CONSERVATION Officer Ralph Von Dane, key man in many Nebraska game law enforcement investigations, exemplifies the high degree of technical skill needed by modern conservation agencies. He is not only a guardian of Nebraska game laws through regular patrol assignments but is also pilot of the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission plane.

Teaming up with other Conservation Officers who are stationed in patrol cars and equipped with two-way radios, Von Dane has cooperated in some of the biggest game violation cases successfully brought to prosecution in Nebraska. One of the more common types of cases these teams work on are illegal fishing involving fish traps. Flying over streams, usually with a local officer accompanying him, Officer Von Dane locates the fish traps. Unless the water is very muddy, these illegal traps are easily spotted from the air.

After locating the trap, the local Officer keeps constant watch on it until the violator comes to remove the fish. Occasionally it is necessary to keep watch on the traps by plane and notify the ground-stationed Officers by two-way radio so they can move in to make the arrest. In a recent case, the highly coordinated team of Officers brought to prosecution one case of illegal fishing that cost the violators a total of $711 in fines, court costs and liquidated damages.

Another type of game violation case that involves the plane-car-radio team is illegal shooting, usually from a car or a highway. In the past antelope season two different hunters were quite surprised to find their violations were witnessed in spite of the remote location of the violations.

Both of these cases involved shooting' at game animals from a car. Spotting the violations from the air, Officer Von Dane radioed to a patrol car in the vicinity but out of sight of the violators, and kept track of the violators' cars until the patrol car arrived to make the arrests.

Officer Von Dane is quite enthusiastic about the ease of locating violators that think they are safe from observation. "They just don't seem to think about looking up when they are going to violate the law; they just worry about the patrol cars," he said. "The plane makes many cases for us; cases that would be practically impossible to apprehend," he continued. "Day or night, we can usually spot a violation from the air," Von Dane said. Some of the night-time violations he told of were spotlighting for ducks and pheasants and illegal fishing.

Many of Von Dane's aerial assignments are to aid the Game Management Division in census and survey work. Pre-season survey of the big game areas are part of this work. Waterfowl survey counts are another part.

Another important assignment is aerial photography, which gives the Commissioners a good perspective of various Commission projects throughout the State.

The Commission needed information as to the size and types of agriculture practices in the Gavins Point area on the Missouri River early this spring. With the use of the plane, a cover map was made in a period of a few days. By any other means, two trained persons would have been occupied at least a full week to 10 days for completion of this project.

When Von Dane doesn't have a specific assignment with the plane, he is patroling west out of Lincoln by car. His area includes the west halves of Lancaster and Gage Counties and all of Seward and York Counties. Before being assigned to the Lincoln district, Von Dane was at Hartington for 3 years.

He likes to tell about two men he arrested while he was working out of Hartington. "Just to show you how excited a person will get when taken into court," he begins. "I took these two men into court for fishing without a license. The judge asked if they had anything to say, and this one fellow spoke up: "We weren't really fishing but just had our lines in the water to see if the fish were biting."

Von Dane went to high school at College View High School in Lincoln, where he lettered in football and track. He played fullback on the team his senior year. After graduation in 1941, he went into the Army Air Force and was assigned to combat cargo planes.

Von Dane came back to Lincoln in 1946, after his discharge and, still wanting to fly, took flying lessons at a Lincoln flying school under the G.I. bill. Within a year he had enough time to get his commercial pilot's license, flight instructor rating and multi-engine rating. Soon he was working on his instrument license while working as a commercial pilot for a non-schedule charter airline in Lincoln.

Von Dane took a brief tour as a crop dusting pilot in South Dakota and northern Nebraska. He had Mrs. Von Dane convinced this wasn't too dangerous until one day she saw him dusting crops near the airport. Needless to say, she didn't remain convinced.

Von Dane worked as a Conservation Officer for three years before he took on the added responsibility of being pilot in February, 1953. He was transferred to Lincoln at this time, where he and his family still make their home. Mrs. Von Dane is the former Jean Perry, also of Lincoln. The Von Danes were married in 1942 and have two children: a boy, Jim, age 6, and a daughter, Joye, age 10.

The best endorsement of Officer Ralph Von Dane's ability comes from his fellow Officers, who have to fly with him. "I would fly anywhere with him. He can put that plane anywhere he wants to and never takes a chance," is the earnest consensus of their opinion.

24 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

WHAT MAKES FISH WORMY?

by Walter KienerFREQUENTLY the Game Commission gets reports and inquiries regarding "wormy" or "grubby" fish. Fishermen want to know if these fish are safe to eat and why the fish are "grubby." Quite often these fish are simply thrown away, in the belief that they are unfit for human consumption.

The parasites that infest fish and give them the appearance of worminess or grubbiness are usually tiny animals such as crustaceans, flatworms and sometimes leeches.

When a fish has spots or grubs on the outside, particularly near or on the fins, it is usually caused by tiny leeches or crustaceans which are also known as copepods. These minute parasites are attached on the outside but penetrate the skin of the fish. When such a fish is prepared for cooking, the parasites are removed with the scales or skin and with some extra care, the marks of the parasite can easily be eliminated.

The small leeches and crustaceans have a relatively simple life cycle. Since they are always found at or near the outside of the fish, they present no problem and all the fish needs is a good cleaning and cooking when prepared for eating.

When the "worminess" of a fish is caused by a tiny tapeworm, the story is somewhat different because these tiny parasites penetrate not only the skin, but also the flesh of the fish. Although harmless to man if eaten, these wormy fish do create a psychological barrier that prevents many people from utilizing them for food.

The tiny flatworms, technically known as trematodes, present a different story. They have a complicated life cycle. These parasites in their cycle of life, that is from birth to reproductive maturity and death, need three hosts on which to live and draw food. These three hosts usually are: first, a water bird; second, a snail; and third, a fish. The snail is the most important host for the parasite, and this is where the greatest amount of reproduction takes place. When the parasite's offspring leave the snail they must become attached to a fish or else they perish.

The fish becomes an intermediate host in the life cycle, and it is only when the parasitized fish is eaten by a fish-eating bird that the parasite can continue its life cycle.

In the bird, the full grown parasite produces eggs; and dies. The eggs, after a while, develop into free swimming organisms which start hunting for snails to which they become attached and then burrow themselves into the snails and undergo more changes.

While living parasitically in the snail, in a sort of a larval stage, they reproduce many more larval offspring. After development, these offspring change into new forms which leave the snail and swim about with the purpose of finding fish hosts to attach themselves to. While living as parasites in the fish, they again change into a different form; this time into that of an adult tapeworm. These adult tapeworms then can reproduce themselves only in the bird after the parasitized fish is eaten by the bird. Then the life cycle starts all over.

The grubs found in Nebraska are chiefly of three kinds. The most common is known as the white or yellow grub and this is the one in which the grubs penetrate the deepest into the flesh. In the black grub, the parasites appear as black dots and are found most often near the skin. They are, therefore, easy to clean. A third grub is known as the white grub of the liver, is usually restricted to the entrails of a fish and does, therefore, not affect the looks of the fish or its flesh. So far it has been found mostly only in minnows within Nebraska.

The grubby fish might be abhorrent to most people, but they certainly are not harmful when well cooked. The grubs are only a part in a cycle of life, in which the basic organism changes its form about six times, and alternately has to live off a snail, a fish, and a bird. Truly this is at the same time a puzzle and a wonder.

Answers to OUTDOOR QUIZ

Score 5 points for each correct number and 10 points for each correct name. If you score 90, you can rate yourself an expert on wildlife plants of Nebraska, 75 is good and below 65, poor.

A. No. 3, Sumac; B. No. 6, Wild Plum; C. No. 1, Osage Orange; D. No. 4, Cedar; E- No. 5, Chokecherry and F. No. 2, Multiflora Rose.

FOCUS THE PICTURE SHRIKE

Noses on Nebraska Fauna

This is the twentieth of a series of articles and drawings depicting Nebraska wildlife. The article was written by Goodman Larson, Fish and Wildlife Service, Grand Island, and the drawing was prepared by Staff Artist C. G. "Bud" Pritchard. The Winter Issue of OUTDOOR NEBRASKA will feature the mink.

CANVASBACKMR. Nebraska Duck Hunter, what's your favorite duck? If by chance the largest and fastest flying duck were also the best eating duck, isn't it logical that this duck be proclaimed as a favorite? I believe the canvasback meets these requirements and can justifiably be referred to as the "King of Ducks." Do you agree?

A canvasback drake will weigh 3 pounds and a hen 2 pounds 13 ounces, on an average. So you see the "Can" is substantially larger than second-place mallard at 2 pounds 11 ounces and 2 pounds 6 ounces.

When you start comparing speeds in ducks you are really getting into an argument. Kortright's book on Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America, lists the canvasback as the fastest duck at 72 m.p.h. air speedchased. Therefore, with a 28-m.p.h. tailwind a lone "Can" could dip down over your decoys moving at 100 miles per hour. The canvasback is certainly the jet bomber of the Duck Corps. He's streamlined for speed, has a wing surface 20 percent less than that of the mallard and therefore must have a faster wing beat to stay airborne.

The first juicy taste of a corn-fattened greenhead or a small but mighty blue-winged teal is hard to surpass, but if the old adage "the proof of the pudding is in the eating" applies to ducks, the epicure's choice is the canvasback.

Although the canvasback may occur anywhere in the state, it is not at all a common duck. Canvasbacks comprise only 3 percent of the breeding population of ducks in the western sandhills and are much less frequently found elsewhere in the sandhills.

In the entire Central Flyway, canvasbacks comprise about 4 percent of the total duck kill. Mallard, pintail, green-winged teal, and scaup are shot in greater numbers. Here in Nebraska the canvasback is even less common. Most Nebraska hunters don't normally shoot many canvasbacks. During the early part of the fall the local canvasbacks tend to concentrate on certain of the sandhill lakes where their favorite foods and other conditions are to their liking.

The southern migration of the canvasback takes place in a short period of time and these birds normally do not loiter long on the rivers or reservoirs where most Nebraskans do their shooting. During a 4-year period there were only 32 canvasbacks, out of a total of almost 8,000 ducks, checked at the Ogallala dressing station.

The canvasback is a true American and is not found outside of the New World even as a straggler. They winter along both coasts, the Gulf, and central Mexico. By mid-March some small flocks of canvasbacks start moving into Nebraska. Most of them will linger for a while on the lakes, reservoirs, and ponds, and then move on north into the Dakotas or Canada, where they will nest. A few will select breeding sites on the lakes and ponds in the western sandhill region of our state.