OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

SUMMER ISSUE 1954 15c

Outdoor NEBRASKA

Vol. 32, No. 3 EDITOR: Wallace Green Artist C. G. Pritchard Circulation Marjorie French Leota Ostermeier COMMISSIONERS W. O. Baldwin, Hebron, chairman; Donald F. Robertson, North Platte; Harold H. Hummel, Fairbury; Frank Button, Ogallala; Bennett Davis, Omaha; LaVerne Jacobsen, St. Paul; Floyd Stone, Alliance. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: Paul T. Gilbert. CONSTRUCTION AND ENGINEERING DIVISION: Eugene H. Baker, supervisor. FISHERIES DIVISION: Glen R. Foster, supervisor. GAME DIVISION: Lloyd P. Vance, supervisor. INFORMATION DIVISION: Wallace Green. LAND MANAGEMENT DIVISION: Jack D. Strain, supervisor. LAW ENFORCEMENT DIVISION: William R. Cunningham, supervisor. LEGAL COUNSEL: Carl H. Peterson. HOW TO SUBSCRIBE OUTDOOR NEBRASKA is published quarterly at Lincoln, Nebraska, by the Game, Forestation and Parks Commission. Subscription rates are $1.00 for two years and $2.00 for five years. Single copies are 15 cents each. Remittances must be made in cash, check or money order. Send subscriptions to OUTDOOR NEBRASKA, Department C, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska. CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please notify this department immediately of any change of address to assure prompt delivery of the next issue to the new address. All material appearing in this magazine may be reprinted upon request. NEBRASKA FARMER PRINTING CO., LINCOLN. NEBR,Editorial

As your new editor, I would like to take this opportunity to let you get acquainted with me. First, you probably would like to know something about my background,

I recently graduated from Iowa State College, where I took training in Wildlife Conservation and Journalism, I mention this so you may understand that I have the basic tools to do the job of editing your OUTDOOR NEBRASKA. 1 certainly don't mean to imply that I don't have a great deal to learn about your wonderful state of Nebraska, but only that I am qualified to help you get information about your State's hunting and fishing and help keep you informed of your Game Commission's activities.

I have recently traveled through a few parts of the State. Your huge reservoir chain, the Wildcat Hills and adjoining Scotts Bluff country, the beautiful and unique Sandhill country, Arbor Lodge and the Missouri bluffs region—all of these have pointed up the wide variety of hunting and fishing available to Nebraskans and have made me proud to be a "Nebraskan-in-training."

Coming to the Nebraska Game Commission at this particular time is fortunate in a particularly interesting respect. To be here at the beginning of the present reorganization plan, to have the opportunity to see it grow and be a part of this growth will be particularly gratifying to me. I hope that through this magazine, I can perhaps share some of the Commission's enthusiasm for the plan and keep you posted on its progress.

I knotv that many Nebraska sportsmen are ivholeheartedly endorsing the Game Commissioners' policies. While attending the annual meeting of the Council of Wildlife Clubs at Kearney in May, 1 saw delegates from all over Nebraska get the attention of the floor during the afternoon session and voice their club's approval of the Commission by saying: "On behalf of the-------------— Wildlife club, I wish to thank the Game Commission for the helping hand they have given the pheasants in our county with habitat planting and to tell them to keep up the good work."

These testimonials for the Commission's practices and endorsements of its> policies were very encouraging to a newcomer like myself. They gave me tangible evidence of the recommendations I have heard from professional wildlife conservationists for the Nebraska Game Commission and its personnel.

I am sure that Nebraska is over the hump, so to say, on the rough and sometimes heartbreaking road to modern game management. I don't mean to say that this road is a short or an easy one. But, if you could find a guide post on this imaginary road, I am sure that it would be labeled "Cooperation and Understanding."

You outdoor sportsmen and landowners will have to bear with the Commission as it progresses towards the goals desired by both of you.

You sportsmen tvill have to continue to carry your banner of cooperation to the door of the landowners and treat them with the respect they deserve and are beginning to demand.

You landowners will have to continue to carry your responsibility for Nebraska's free hunting heritage, evolved from our pioneer fore-fathers as you have done so graciously in the past.

We, of the Game Commission, will have to tackle the many deversified problems at hand with an open mind and trust in the Almighty.

EDITOR: Wallace Green

IT'S YOUR HERITAGE

Evolved from the blood, sweat and toil of early Nebraskans, the future of this hunting heritage belongs to you.ONE of the basic concepts for each of us is our inherent right to hunt and fish. Of course, we have to conform to rules of conduct that will make our present tolerable to the landowner on whose land we wish to hunt and fish. We also have to pay a small fee and abide by a few game laws.

If we meet these basic requirements, then we feel that we have as much right to participate in outdoor sports as the next man. Let anyone attempt to take this inherent right to carry arms and hunt and fish away from us and a great hue and cry would arise.

We take this right for granted, seldom ever having the occasion to even question the possibility of losing it. Certainly, few of us stop to consider where we derive this right.

We vaguely pin a label on the source, such as "our pioneer forefathers," and let this heritage go at that. If we want to trace this heritage of hunting and fishing rights, we would have to go back before Nebraska became a territory, back to the days of the Indians, even back before the French trappers arrived here.

There were two kinds of Indian tribes in Nebraska. Some of the tribes were living in permanent villages with agriculture as their primary means of making a living, with hunting only a means to supplement the larder. These corn growing tribes were located along the Missouri river and consisted of the Omaha, Ponca and Otoe tribes.

Shortly before the arrival of the white man, whole tribes of Indians came west, being driven out of the east and south by earlier contact with the white man. These groups, such as the Dakota, Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes, became the hunters of the prairie country. No longer did they till the land like their ancestors, but instead they became the horse-riding buffalo hunters of the plains.

Everything in their culture was directly dependent on the hunt. Clothes, food, shelter and even their primitive religion was interwoven with this nomadic hunting economy. Where the buffalo herd went, so went the hunter Indian, on horses that were descendants of the horses brought to North America by the early Spanish explorers.

The first white men to come into Nebraska were the French trappers, missionaries and explorers. One group was after conquest of land for the mother country, another after conquest of the devil and the last group was out to conquer poverty by reaping in francs from the immense treasury of fur that was available.

Huge numbers of wildlife: buffalo, elk, deer, antelope, beaver, mountain sheep, bear, waterfowl of every description and many others were common in this area. The Indian was an active conservationist, taking only what he actually needed of these populations.

Conservation was such a natural and ingrained pattern that the plains Indian even had closed seasons during the breeding season of the game that was the basis of his livelihood.

So rigid were the penalties for violating these tribal game laws that

often the sentence would mean extreme

SUMMER ISSUE

3

hardship or even slow death.

Each brave had two horses: One was a

light speedy horse for the hunt and the

other was a rugged, sturdy horse for

use as a pack animal.

hardship or even slow death.

Each brave had two horses: One was a

light speedy horse for the hunt and the

other was a rugged, sturdy horse for

use as a pack animal.

Early market hunters contributed much to the first lesson of game management in Nebraska. The folly of continual heavy hunting pressure, especially spring shooting, was soon apparent as game became more scarce.

The usual sentence for game law violators was to kill one of their horses. Either horse would do, so, needless to say, tribal game law violations were few and far between. For the convicted game law violator, if he survived, one such sentence was a hard lesson.

This was the type of man the plains Indian was: A hunter, whose livelihood was sometimes hard, sometimes exciting and depended directly on his skill and strength on the hunt.

The first white men, French trappers, quickly adapted to this hard way of life. Often as not, they would live with the Indians as friends and brothers, rapidly becoming more Indian than white men in action and custom. From these positions of acceptance in the tribes they began trading for the prized beaver pelts.

Other pelts were accepted, but the premium prize was the beaver pelt used for the beaver skin hats of the eastern gentlemen. Often these trappers would become so well integrated into the ways of the Indian, that they would not come out of the wilderness for years.

Other white men made a profitable living bringing barter supplies to the trappers. Being Frenchmen, they named their meeting places "rendezvous," meaning place of meeting. This is undoubtedly, where we eventually picked up the word and absorbed it into our language.

This was the pattern for a number of years; trappers were taking many pelts, with the aid of their Indian friends, and yet, they didn't do any great damage to the over-all wildlife picture.

In the beginning of the 19th century, France's Napoleon got into financial trouble while trying to conquer Europe. Relief for an empty treasury was gained by selling land and the Louisiana Purchase was made by the United States in 1803.

This change in ownership of the future Nebraska Territory gave the Americans the chance to get into the fur trade in a big way. Soon companies such as the St. Louis Fur Company, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and the American Fur Company were formed and centered in the former French headquarters town of St. Louis.

The flow of fur continued to come into St. Louis over the water highways such as the Platte and the Missouri rivers. Loading their furs into bullboats, which were the round, Indian style, boats made from a single buffalo hide, they would float downstream to meet the big keelboats of the Missouri river. Often the furs would bring the trappers a 200 per cent profit at the markets in St. Louis. On the return trip, the keelboats would be loaded with supplies and barter items.

Not everything went smoothly with the traders and the Indians. Renegade Indians were raiding for supplies rather than trapping all year and trading for a few trinkets.

The United States established Fort Atkinson primarily to protect the thriving fur trade from the Indians and to help check the growth of British power. Much of the soldiers' time was spent cultivating 500 acres of land to help make the fort self-sufficient.

Although the fort was in operation only a few years, one very significant thing evolved from its establishment. For the first time the prairie had been broken and planted in agricultural crops by the white man. The prairie could grow crops and excellent ones at that. This fact was to be ignored for a number of years.

Things went along as they had been, the fur trade was steady with the usual troubles with some of the Indians, and for those days, it was pretty quiet.

In the early 1840's the Oregon Territory was opened up and people wanted to go there to settle on the cheap land and start a new life. The army sent Lt. J. S. Fremont into Nebraska to find a route for the wagons to travel on. Fremont returned and his report on the Platte Valley was published far and wide People eagerly read the accounts of the good wagon route to the west.

Soon the Oregon trail was more than a newspaper account. People were headed west, a few wagon trains a year, at first. Then the news came from California that swelled the numbers of emigrant wagon trains within a year's time. "Gold! Gold at Sutter's mill," and the rush was on.

Yet it wasn't gold that changed the lives of the fur trappers, only the fickleness of fashion in the east.

The beaver skin hat went out of style. Men of quick thinking, the trappers soon were utilizing another animal of the plains. This utilization was soon to become a slaughter, a slaughter which probably will never be equaled. The buffalo was the answer to the changed style and the fur industry quickly capitalized on the strong, warm buffalo robes in place of the beaver hat.

Soon the trappers, now hunters, were following the herds, much as the Indians did. The only limit the white hunter had on the number of kills made in a morning's hunt was the number that could be skinned by sundown.

It wasn't long before enterprising buffalo hunters developed a very rapid method of skinning a buffalo by using a team of horses to jerk the hide. This greatly increased the number of buffalo killed in one day.

Between their own greed and the

coming influx of emigrants, the days

4

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

of the buffalo hunter were numbered.

of the buffalo hunter were numbered.

Growing numbers of people in the Nebraska area created a demand for government and in 1854 the Nebraska Territory was created. There were outfitting stations and Army forts throughout the newly formed territory and the stage was set for a century of change.

After numerous clashes with the ever-increasing numbers of emigrants and the inroads, made on the buffalo herds by the hunters, the Indians were soon fighting valiantly, desperately, and finally, hopelessly for existence.

A popular idea, both with the Army and civilians, for defeating the Indian, was to eliminate the buffalo herds and thereby eliminate the means of the Indian's existence. This theory gave the buffalo hunters the support of public opinion and the slaughter continued.

Enterprising men of the east were quick to recognize the west for an unequaled opportunity for development. Cheap land and the Homestead Act of 1862 were the answers to the literal prayers of thousands at the end of the Civil War.

Within a few years, a great land boom developed and the Territory was attracting far greater numbers of people than even the gold of the Black Hills and California.

The railroads had already reached the Platte Valley. Texas ranchers were pushing cattle up north to the rail headings at Ogallala, Kearney, Schuyler and Omaha. Many a trail drive supper consisted of a deer or antelope shot along the trail, rather than butchering some of the precious beef.

Both the buffalo and the Indians were on their way out. With the great influx of emigrants, much of the other wildlife of the prairie was doomed. This fact was not apparent at the time and everyone in the west supplemented his welfare with wild game. It was more than a sport, yet these early westerners had their own code. A gun was their way of life, whether aimed at game or an enemy.

Crazy Horse and his people were finally defeated in 1877 and the final barrier to settlement in the Territory was at an end.

The homesteaders and the early ranchers had completed their years of open warfare, with the homesteaders getting the edge due to increased acreage allowances and the establishment of a legal system to protect the rights of landowners.

In the more thickly settled eastern part of Nebraska, the people wanted better fishing and soon created the early parent of the present day Game Commission. In 1879 the Board of Fish Commissioners was established to promote the propagation of fish. Dismal failure faced the Commission for the first few years. Mistakes such as attempting to propagate and stock whitefish in the warm water temperatures of the eastern streams were almost fatal to the Commission. They were greatly hindered by the lack of funds.

The next twenty years found the Commission becoming more successful in their only function, raising and stocking fish. Trout, carp, walleye, northern pike and bass were some of the species propagated by this early Commission. They had absolutely no power to enforce game laws. In fact, there were no game laws to enforce.

SCS Photo The drought and the ensuing dust bowl were another severe lesson. Poor agricultural practices, including tilling of marginal land, threatened the existence of both wildlife and even man in some areas. Today's dust bowls indicate we may not have learned this lesson well.

Early homesteaders were faced with many hardships such as drought and grasshoppers Many times when faced with crop failures, the only means of surviving was market hunting.

An early historian says, "The early 1890's were very dry years. In Garden County, the people got by, by market hunting. They would come home with a wagon load of geese, ducks, prairie chickens, etc. They would dress, pack in barrels and ship them to Denver or Omaha."

A few prices from a market report of H. L. Brown and Sons, a produce commission house in Chicago, that bought many wild birds and animals, are as follows: prairie chicken, $4.00 per doz.; quail, Prime No. 1, $1.50 per doz.; venison saddles, 13c per pound; mallard ducks, $3.75 per doz.; redhead ducks, $3.75 per doz.; canvasback ducks, $10.00 to $16.00 per doz.; jackrabbits, $3.00 to $4.00 per doz.; and bluewing teal, $2.00 per doz.

The truly professional market hunters were responsible for much of the disappearing wildlife. These hunters, not only Nebraskans, but also easterners, coming in to hunt the big migration flights, decimated the waterfowl populations and made grim swaths in other wildlife populations.

Most of the buffalo, deer, elk and other big game had disappeared due to local hunting pressure and the destruction of their habitat.

The elk herd of Nebraska lived in the heavily timbered feeder streams of the Niobrara river and the Loup river watershed. Hugh cedar, fir and pine trees, often 40 feet high, were prized by the settlers for building and soon the home of the elk herds was destroyed.

Agriculture practices were detrimental to wildlife as they changed the face of the land, offering no cover for much of the year. Combined with the indescriminant and heavy hunting, the agriculture practices of the settlers added the straw that broke the back of the hugh wildlife populations.

Drainage, spring burning and breaking prairie sod to plant crops on marginal land were the most detrimental of these agricultural practices.

Only the visible diminishing of game populations could stimulate the people to consider regulating hunting and

(Continued on Page 17) SUMMER ISSUE 5

WHO SAYS BULLHEADS ARE HARD TO CLEAN?

A cleaning board, made from a l/z inch plank with a nail driven at an angle; a sharp knife and a pair of skinning pliers are the only tools needed to clean bullheads with ease.

Grasp the skin of the bullhead with the skinning pliers in one hand. Grip the tail of the fish firmly, with a little backward pull, in the other hand. Now, a steady pull on the pliers will take the skin off with ease.

After impaling the bullhead through the lower jaw on the nail, make a slit in the flesh, just behind the hard surface of the head and extending to the belly.

After skinning out both sides, a deep cut is made through the backbone of the fish behind the head. This cut should be through the flesh and bones, but be careful not to cut into the internal organs.

Make a second cut along the backbone, running down to the tail. Neither of the two cuts should be deep, but just enough to cut through the tough skin.

Grasp the flesh and backbone of the fish behind the head and give a steady pull, up and backwards, with one hand while holding the tail firmly with the other. This will leave the unwanted portion of the bullhead impaled on the nail.

The Key to Better Hunting and Fishing— THE NEW REORGANIZATION PLAN

YOUR Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission is coming to you. No matter where you live, whether it is deep in Cherry County in the Sandhills or in Richardson County in the most southeastern corner of the state, there will soon be a task force of trained biologists working on your local fish and wildlife problems.

This grassroots scheme is known as the reorganization plan.

The main idea in the decentralization of the Game Commission field activities is the breaking of the state into five areas. These areas, to be called districts, will have a field office headquarters. There will be a complete staff of highly trained personnel located here, to carry out all phases of Commission field work in the local area.

In each district there will be a game manager, a fish manager, a land manager, a law enforcement chief and a multi-purpose labor crew with a superintendent.

What will it mean to you as an outdoor sportsman? It will mean primarily that you have highly trained men, whose business is your sport and recreation, living in your locality and working on your local fish and wildlife problems.

These field biologists will be the starting link in a chain of information needed by the administrative office of the Game Commission in Lincoln, to formulate policies to improve your hunting and fishing. They will be out in the areas where the various game problems originate, collecting information and making recommendations to remedy these problems.

Decisions to correct your local wildlife problems will be based on this grassroot work of the field biologists. As the Commission gets a better overall picture of the facts about Nebraska wildlife, it will be more able to "do something" about the problems concerned.

These biologists will also be responsible for putting these policies in action after getting approval from the administrative office. Here you see the end of the chain that starts with the investigation of a problem on a local level and, after going to the administrative office for analysis and decision, is put into action by the very personnel that explored the problem.

The reorganization plan will mean that you will have much easier access to information about the activities of the Commission. These field biologists will be available for public programs such as wildlife club meetings, school, civic and church programs.

As these men have had years of experience and training, they will be able to tell the story behind the technical side of wildlife management. The Commission feels that only after the landowner and the outdoor sportsman get a basic understanding of wildlife problems, can it expect the enthusiastic support that produces top-notch game management.

You will get a better buy for money spent for licenses and federal taxes on arms, ammunition and on fishing tackle. There are two federal aid programs, Dingle-Johnson and Pittman-Robertson, that allocate this tax money for research and restoration work.

The Dingle-Johnson program, supported by a fishing tackle tax of 11%, distributes money based on Nebraska's share of this federal tax. We must match one dollar for every three dollars provided by the federal government for use by the Commission in research and restoration or acquisition work.

In the fisheries work, both research and acquisition of land are of primary importance. Because the range of fish is limited, obviously, to water areas, the best restoration program is based on increasing the water areas. Nebraska's Grove Lake project is an excellent example of this procedure.

The Commission, working closely with the Federal Aid Division of the Fish and Wildlife Service, acquired 426 acres and completed the development at a total cost of $42,600. Now the actual cost to your Commission was a little over $10,000 as the project was 75% reimbursable from the tax on fishing tackle sales that had already been collected from Nebraska fishermen.

The Pittman - Robertson program works essentially the same way, as far as the financing is concerned. Of course, the money comes from an 11% federal tax on arms and ammunition.

The big difference between the fish and the wildlife programs is that the latter is centered around habitat restoration, rather than land acquisition.

This map shows the boundaries of the proposed five districts. Each district will have a chief warden, fishery manager, wildlife manager, land manager and a construction foreman with a labor crew. The location of the district headquarters has not yet been determined.

As most species of wildlife are distributed over large areas of the state of

Nebraska and located on private land,

for the most part, the Commission

deems it best to improve the habitat

SUMMER ISSUE

7

over these extensive areas. It wouldn't

be very feasible to procure much

land, especially at today's land prices,

and put in intensive cover restoration

work.

over these extensive areas. It wouldn't

be very feasible to procure much

land, especially at today's land prices,

and put in intensive cover restoration

work.

For this reason the habitat improvement crews, under the direction of Wade Hamor, Habitat Leader, have planted over 1% million trees and shrubs on habitat areas during the 1954 planting season. Most of these habitat areas are located on private farms in widespread areas throughout the state.

Unfortunately, the fixed overhead of the Game Commission has not allowed taking full advantage of total amount of federal aid available. The Commission just hasn't had the money to match with Nebraska's share of federal aid funds. This fixed overhead has been absorbed in the spiral of everrising costs for salaries, subsistence, vehicle and equipment costs and maintenance.

The "twenty-five cent" dollar has hit the limited budget of the Game Commission very hard in this respect. One of the main ideas in attempting the reorganization is to lower this fixed overhead and make more money available to use with Nebraska's share of federal aid funds.

As you can see in the accompanying organizational charts, there are 61 employees on the old plan charged with maintenance, planting or construction. Much of the work in these three categories is seasonal.

GAME FARM STATE TRAPPER HABITAT LEADER 10 THREE MAN CREWS

In the new plan, a multi-purpose labor crew will take over the functions of all of these crews and will be located at a district headquarters.

A new policy for planting habitat areas will cut down a large part of the fixed overhead. Under the old plan, the habitat crews build the fences in the fall for the areas to be planted the following spring. After the spring planting, these crews have had to take care of the first summer's cultivation.

Under the assumption that more participation on the farmers' part may instill more sustained interest, the following policy has been established. The Game Commission will furnish the technical advice and the material to fence the habitat area. The farmer is expected to take care of the necessary cultivation. This plan should release thirty men from the habitat crews. The planting work will be done by the multi-purpose labor crew, located at one of five district headquarters.

This multi-purpose crew will also take over the duties of the recreation ground crews by doing the maintenance work of its own district recreation grounds. The elimination of the recreation ground crews will release nine more men.

The six man reservoir crew will be cut in half. The remaining men will get assistance in large jobs from their local district labor crews. The surveyor position will be eliminated. The work done by the surveyor will be contracted locally. The district biologists will be charged with assisting in the animal removal work, when needed.

The 16 man construction crew will be increased to a total of 23 men, broken into five crews and will be given a multi-purpose assignment, covering the above mentioned operations. The size of the anticipated multipurpose labor crews will be as follows:

Area 1—One superintendent and two men.

Area 2—One superintendent and two men.

Area 3—One superintendent and five men.

Area 4—One superintendent and five men.

Area 5—One superintendent and four men.

There will be a conservation officer chief appointed in each district. At the present time. William Cunningham, Supervisor of the Law Enforcement Division, is in direct charge of all of the officers. He cannot give any large degree of personal attention to the individual officer's problems, nor can he give detailed direction to their activities.

With the assistance of the five district chiefs, he will be in a better position to integrate the law enforcement division into a more efficient group.

The establishment of the district headquarters will also provide a central location for specialized equipment such as boats, safety and radio equipment. This equipment will be issued to officers by the local district chiefs.

No change in the number of personnel in the law enforcement division is planned, as the officer chiefs will be selected from the present compliment. There will be two important changes in the game management division.

There will be five game managers, with one being assigned to each district. These men will be trained academically and will be well versed in the practical application of game management techniques.

Each game manager will be responsible for studying the causes of the rise and fall of game populations in his district. He will also develop methods for continuous inventories of the game populations in his district. Local pheasant booster units will be under his supervision.

Athough the game managers will be responsible for all of the game population in their districts, the location of the districts will somewhat limit this responsibility to only one or two species of game birds or animals.

By looking at the map of the districts on this page, you can readily see that the game manager in District 1 would be primarily concerned with antelope, deer and ducks. In District 2 the stress would be on muskrats, grouse and ducks. In Districts 3, 4 and 5, pheasants and quail would have priority.

A game project leader has been established to carry out liaison between the game managers at the district level and the supervisor of the game management division. He will also co-ordinate game division work with related divisions. His duties will be to draw up investigational projects, allocate them to the proper game managers and check on progress. Dr. Henry Sather, who tells of a new pheasant investigation program elsewhere in this issue, has been assigned to the position of project leader.

Five fish managers and one project leader will have the same general duties as outlined in the game division. Of course their assignment will be on fish rather than game.

Each fish manager will be responsible for the fishery management of the waters in his district. Some of their duties would be analysis of the water areas, checking the fishing success and creel census work, age and growth studies, population studies, and attempting to determine the cause of the rise and fall of these populations.

A new position has been established, that of land manager, to foster better understanding between the Game Commission and the farmer, on whose land the large majority of public hunting is done. The personnel selected for this position will have to have a formal education in both farming and wildlife management. They will work continuously with the farmer, the Soil Conservation Service and the County Agents in an effort to include wildlife into the farm conservation story.

Most of their technical work will be in habitat or cover improvement projects. They will plan new plantings, evaluate old plantings and study the need for modifying our present planting procedures.

Once again, we see the need for a project leader being fulfilled. Mr. Wade Hamor has been assigned to the position of land management project leader. His duties will entail the same general procedures as the other project leaders, but naturally, he will be concerned with land management.

The salaries of the game, fish and land managers and their respective project leaders will be partially reimbursable with federal aid money. In all work that is part of an approved project, the Federal Fish and Wildlife Service will allot aid from either Pittman-Robertson or Dingle-Johnson funds. Federal aid will also be available for some phases of work performed by the multi-purpose labor crews such as habitat and acquisition work.

You can see the general pattern of the reorganization will put game and fish management on a local basis and take greater advantage of the federal funds available for this work.

The better understanding of the common problems of the sportsmen, farmers and Game Commission, made possible by this new plan, should evolve in clearer management goals and better co-operation from all three parties. This will in time, mean better hunting and fishing for you and other Nebraskans.

Meet Your Conservation Officer

Conservation Officer Bernard Patton, better known as Pat, could also be called the River Man because of his wide variety of experiences on Nebraska's big Missouri river. At one time or another, during his eight years with the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission, Pat has traveled most of the river from the South Dakota to the Kansas-Missouri limits.

Pat is a quiet and unassuming individual with a warm smile and a twinkle in his eye. Although he has a reputation for being a "tough officer," his consideration and fairness has won him many friends and supporters in District No. 27. This area includes the eastern halves of Lancaster and Gage counties, and all of Otoe and Cass counties.

Commercial fishermen on the big river have become acquainted with Pat due to a net sealing plan worked out by him and Ed Cassell, when Ed was also a Conservation Officer.

Pat explains, "Ed and I worked together on the river and we thought that if the commercial nets were sealed with a tag that had a serial number, it would make it easier to identify them and save us waiting around for the owner to run the net.

Although it seemed like a lot of extra work, we also thought that if we sealed the nets personally, we would have the opportunity to meet each commercial fisherman and could start out on the right foot with them." After the two Officers presented the plan to their superiors, it was readily adopted.

When questioned about the future of the commercial fishing on the Missouri, Pat explained, "Each year the commercial catch has been growing smaller. After the changes made in the river by the flood control interests, the catch has been reduced until there isn't enough money in commercial fishing to attract anyone, except as a sideline." "Many of the old time commercial fishermen," he pointed out, "have made their last trip on the river and there just aren't many young men starting in it. By the time a man would get all the equipment necessary to go into it right, he would have too much money tied up for the return he would get," he concluded.

One of the strangest court convictions was made by Pat this spring. The charge was taking deer out of season, a happening that most of us would associate with the western part of the state. Two men were in their boat, moving along at a good pace with an outboard motor, when they spied a deer swimming in the stream. They proceeded to run the deer down, lasso it with a rope and drag it until the animal drown.

Evidence of the respect Pat has gained in his area is seen from the fact that he was given the necessary information to gain a conviction although he didn't observe the incident.

Pat tells of a tragic aftermath to a law violation case. One week after being convicted for seining for fish in a sandpit lake, one of the principals in the case was drown—seining for fish illegally in the same sandpit lake.

Pat started working for the Game Commission in the spring of 1947. He worked for a telephone company about a year before this.

He was one of the first of the "1 year" inductees in the Army. Pat went into service in February, 1941. Of course, Pearl Harbor, changed the plans of Pat, along with the rest of these "1 year" draftees.

Attached to the 134th Infantry, 35th Division, Pat landed on the beaches of Normandy in 1944. From this landing on Omaha beach, with the first of the invasion forces, to the occupation of Hanover, Germany was the long road that Pat followed in the "walking Army." In November, 1945, the long awaited day arrived and Pat was once again a civilian.

Pat and Mrs. Patton, the former Netta Rodel of Blair, have two children. The oldest, Douglas is 4 yers old and youngest is Debra, who is 20 months old. The Pattons make their home in Lincoln.

FOCUS THE PICTURE

Following are characteristics of a game animal inhabiting Nebraska. How many of the characteristics must you read before you can bring the picture into focus?

1. This animal has been a long time resident of Nebraska, at one time reaching a very low population; but, thanks to modern game management, it is now at a high population.

2. It spends a great deal of time in the water and is usually active at night.

3. It has a beautiful fur, which is highly valued by the fur industry. The long guard hairs are plucked off, exposing the soft short underfur, which is luxuriant and beautiful.

4. It is the largest rodent in North America, often making its home in the banks of streams.

5. It is a strong swimmer, using its tail and webbed back feet to propel it through the water at a rapid pace.

6. It is strictly a vegetarian in its eating habits.

7. It has a reputation for being energetic and is usually busy working.

8. It sometimes causes localized damage by cutting down trees and flooding streams.

9. It is well known as "Nature's Engineer" because of its dam building ability.

10. It has a large flat tail, which it uses for a chair on land, a rudder while swimming, a tool for building and a signal for danger by slapping it hard on the water.

See page 25 for answer

10 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

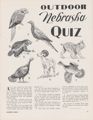

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA QUIZ

ALL of the animals in this issue's Outdoor Quiz are former resdents of Nebraska. For one reason or another, usually due to the impact of modern agricultural practices on their natural habitat, these animals have disappeared from the Nebraska wildlife scene.

A. This bird, a popular eastern upland game bird, at one time thrived in the timbered areas along the Missouri river. No

B. A member of the cat family, this animal was last seen in Nebraska when a quail hunter shot one in 1890, near Norfolk. No.

C. At one time quite numerous in Nebraska, this bird is one of the largest of all upland game birds. No.

D. This animal, feared by trappers in the far North for the damage he does to caches, was common in the thinly timbered canyons in Northwest Nebraska. No

E. A bird with many relatives in South American tropics, was found in large numbers in the Missouri valley. No

F. This bird, now totally extinct, lived in Nebraska in such huge numbers that flocks of them would darken the sky. The last of these birds died in a Cincinnati zoological garden in 1914. No

G. Good size herds of these animals were found near Chimney Rock. The last one reported killed in Nebraska was in 1888 by George Slonecker, in Scotts Bluff county. No.

See answers to Outdoor Quiz, page 24, for details for scoring and correct answers.

SUMMER ISSUE 11

Game Commission Takes a NEW LOOK AT PHEASANTS

by Dr. Henry J. SatherOne of the marking devices to be used in the pheasant study, these two brightly colored plastic strips make easy field recognization of individual pheasants.

Dr. Henry J. Sather explains his proposed study for getting more facts about the lives of Nebraska pheasants for better management.

WE are busy making plans to study, very closely, the day by day, week by week, and year by year activities of our king of upland game birds—the pheasant. Why do we want to delve so deeply into such things? Primarily because only through a thorough knowledge of the pheasants' "facts of life" can we hope to understand—and do something about—their fluctuations in numbers.

The ultimate objective in the management of any game animal is to maintain its numbers at optimum levels. Only through management based upon sound facts can we hope to realize this objective.

Habitat requirements of pheasants will receive top priority in this study. It is certainly true that we already have a good idea of the general requirements of pheasants. If we wanted to manage a piece of land solely for the purpose of raising pheasants, we could do a good job of it with the information that we already have at hand. However, that type of land management does not fit in too well with the economically sound land use programs of our rapidly developing age of intensive farming.

Intensive farming is here to stay. Technological advancements in the land use field during the past few vears indicate that we are on the road to what might be called very intensive farming. Much of the waste area, which in the past has been left for wildlife, will, in all probability, in the future be converted to crop producing land. In view of this trend, it seems quite likely that any habitat management for pheasants in the intensive farming picture will, of necessity, be limited.

For that reason, it is extremely important that we have some knowledge of the minimum habitat requirements of pheasants and how these minimum requirements can be integrated into an economically sound land use program. The future of public hunting of pheasants depends upon the solution of this problem. What we put on the land for pheasants will be limited so we must be absolutely sure it is effective.

Another phase of the study that will receive high priority is the stocking question. Is stocking a complete waste of money? Is there a time and place for the use of stocking as a management tool? If so, when and where? How do wild trapped birds compare to game farm birds in stocking programs? Those are a few of the questions that we will be looking for answers to.

There are many other facts about pheasants that we will want to ferret out. For many years we have had extensive pheasant survey systems designed to give us an idea relative to the statewide pheasant picture. In general these surveys have furnished us with a good picture of what is happening to our pheasant populations, but we have frequently been at a loss as to explain why. We need more facts for the correct analysis of these surveys.

Since the study is still in the initial planning stage, the plan of action is, as yet, rather general. Three study areas will be established in our good pheasant range. In deciding upon the exact location of these areas we will have three things in mind. First, the areas must be close enough together to be studied thoroughly and yet far enough apart to rule out any influence of one area upon another. Next, they must be located in a region that has supported good pheasant populations over a relatively long period of time. Thirdly, they must be in a region that has traditionally been subjected to rather heavy hunting pressure.

Each of the areas will be at least 5,000 acres in size. Area No. 1 will not be subjected to habitat manipulation. A carefully planned program of stocking will be carried out on this area. It is believed that answers to our stocking questions will be obtained within approximately a three year period. Upon completion of the stocking phase on this area, a program of habitat manipulation will be initiated.

Area No. 2 will never be subjected to a stocking program. Habitat manipulation will be the only management measure carried out on this area. Area No. 3 will be what can be called a check or control area. No planned program of stocking or habitat manipulation will be carried out on this area. It will be a check on what is happening to the pheasant population in the absence of the planned management efforts being used on the other two areas.

In order to obtain detailed coverage of what is happening on the areas, two men trained in the game management profession will be assigned to the study. They will be using a great variety of special techniques that have been developed for the study of birds in the wild. Such techniques include cover mapping, live trapping, banding and color marking, nesting studies, etc. These men will be digging into the innermost secrets of the life of the pheasant in an effort to obtain the facts needed for sound and effective management.

12 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA Dr. Sather's three study areas

Dr. Sather's three study areas

Carefully planned stocking will of this area.

Habitat manipulation will be the only measure taken on this area.

Neither habitat manipulation nor stocking will be done on this check area.

Wildlife in one reel

BULLS

f1 1600-2000 LBS

WEIGHT

FROM FLIES AND SUN,

DING THEIR SHAGGY

T, THEY ROLL AND KICK

LES IN THE GROUND,

WAY, FILL WITH RAIN

MAKE THE MUD-

OTHING WALLOWS.

•FALO ARE THE MOST

RIOUS OF WILD CATTLE,

N HUGE HERDS THAT HAD

NUALLY MOVE IN SEARCH

OF FORAGE.

BESIDES THE WHITE MAN, THE

BUFFALO HAD FEW PREDATORS.

WOLVES,BEARS,COUGARS AND

COYOTES SOMETIMES PREYED

ON THE WEAK, BUT THEY USUALLY

FED AS SCAVENGERS ON THE

CARCASSES OF THE DEAD.

THE YEAR AROUND LIVELIHOOD OF

THE INDIAN DEPENDED DIRECTLY

ON THE BUFFALO. FOOD, CLOTHING,

SHELTER,AND UTENSILS WERE

PRODUCTS OF THE SUCCESSFUL

BUFFALO HUNT, WHICH WAS

NTERWOVEN WITH THEIR RELIGION.

I

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON'S

ESTIMATE OF 60 MILLION BUFFALO

HAS BEEN ACCEPTED AS THE MOST

AUTHENTIC POPULATION GUESS.

THIS WAS PROBABLY THE LARGEST

SINGLE AGGREGATION OF ANY

SPECIES IN HISTORICAL TIMES.

AS THE WHITE MAN ENTERED THE

WEST, HE BEGAN TO UTILIZE THIS

TREMENDOUS POPULATION. AT FIRST

TRAPPERS USED THE BUFFALO FOR

FOOD BUT SOON A MARKET

DEVELOPED IN THE EAST FOR

BUFFALO ROBES,SMOKED TONGUES

AND BONES.

AS THE RAILROADS

PUSHED INTO THE WEST,

THE UTILIZATION HAD TURNED TO

SLAUGHTER. THE RAILROADS EVEN

RAN EXCURSIONS FOR SHOOTING

THE BUFFALO,WHICH WERE

LEFT TO ROT ON THE PRAIRIE.

IN SPITE OF

THE HEAVY HUNTING

PRESSURE ON THE HERDS, THE

PLOW WAS THE LARGEST SINGLE

FACTOR CAUSING THE BUFFALO'S

DECLINE. FARMING SPREAD OVER

THE PRAIRIE AND THE HABITAT

OF THE BUFFALO WAS DESTROYED.

BY THE TURN

0F THE

CENTURY THE

WILD BUFFALO WERE REDUCED TO

A SCORE OF ANIMALS, LOCATED IN

YELLOWSTONE PARK. THE ONLY

EVIDENCE OF THE HUGE POPULATION

WAS THE BLEACHED BONES IN

REMOTE AREAS.

AS A

RESULT OF

A RESTORATION

PROJECT STARTED IN

IN 1902, THE BUFFALO HAVE

RECOVERED TO OVER 5000. TWO

SMALL HERDS MAY BE SEEN IN

NEBRASKA AT WILDCAT GAME

REFUGE AND NIOBRARA NATIONAL

GAME REFUGE.

BULLS

f1 1600-2000 LBS

WEIGHT

FROM FLIES AND SUN,

DING THEIR SHAGGY

T, THEY ROLL AND KICK

LES IN THE GROUND,

WAY, FILL WITH RAIN

MAKE THE MUD-

OTHING WALLOWS.

•FALO ARE THE MOST

RIOUS OF WILD CATTLE,

N HUGE HERDS THAT HAD

NUALLY MOVE IN SEARCH

OF FORAGE.

BESIDES THE WHITE MAN, THE

BUFFALO HAD FEW PREDATORS.

WOLVES,BEARS,COUGARS AND

COYOTES SOMETIMES PREYED

ON THE WEAK, BUT THEY USUALLY

FED AS SCAVENGERS ON THE

CARCASSES OF THE DEAD.

THE YEAR AROUND LIVELIHOOD OF

THE INDIAN DEPENDED DIRECTLY

ON THE BUFFALO. FOOD, CLOTHING,

SHELTER,AND UTENSILS WERE

PRODUCTS OF THE SUCCESSFUL

BUFFALO HUNT, WHICH WAS

NTERWOVEN WITH THEIR RELIGION.

I

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON'S

ESTIMATE OF 60 MILLION BUFFALO

HAS BEEN ACCEPTED AS THE MOST

AUTHENTIC POPULATION GUESS.

THIS WAS PROBABLY THE LARGEST

SINGLE AGGREGATION OF ANY

SPECIES IN HISTORICAL TIMES.

AS THE WHITE MAN ENTERED THE

WEST, HE BEGAN TO UTILIZE THIS

TREMENDOUS POPULATION. AT FIRST

TRAPPERS USED THE BUFFALO FOR

FOOD BUT SOON A MARKET

DEVELOPED IN THE EAST FOR

BUFFALO ROBES,SMOKED TONGUES

AND BONES.

AS THE RAILROADS

PUSHED INTO THE WEST,

THE UTILIZATION HAD TURNED TO

SLAUGHTER. THE RAILROADS EVEN

RAN EXCURSIONS FOR SHOOTING

THE BUFFALO,WHICH WERE

LEFT TO ROT ON THE PRAIRIE.

IN SPITE OF

THE HEAVY HUNTING

PRESSURE ON THE HERDS, THE

PLOW WAS THE LARGEST SINGLE

FACTOR CAUSING THE BUFFALO'S

DECLINE. FARMING SPREAD OVER

THE PRAIRIE AND THE HABITAT

OF THE BUFFALO WAS DESTROYED.

BY THE TURN

0F THE

CENTURY THE

WILD BUFFALO WERE REDUCED TO

A SCORE OF ANIMALS, LOCATED IN

YELLOWSTONE PARK. THE ONLY

EVIDENCE OF THE HUGE POPULATION

WAS THE BLEACHED BONES IN

REMOTE AREAS.

AS A

RESULT OF

A RESTORATION

PROJECT STARTED IN

IN 1902, THE BUFFALO HAVE

RECOVERED TO OVER 5000. TWO

SMALL HERDS MAY BE SEEN IN

NEBRASKA AT WILDCAT GAME

REFUGE AND NIOBRARA NATIONAL

GAME REFUGE.

You May Hear This Question— SEE THAT TAG?

by Dr. Walter KienerTHAT tag? Oh, you mean that thing in the tail of the catfish."

'Sure, it's small and has a number on it, and it says: Notify Game Commission."

"So what?"

"You're supposed to take that tag off, put it in an envelope and mail it to the State Game Commission in Lincoln. Of course, they want you to tell them on a sheet of paper in as few words as possible, but completely and exactly, just where and when you caught that fish with the tag in the tail. The Game Commission men will appreciate it so much, that they will send you a letter of thanks, and will acknowledge your good sportsmanship and willingness to cooperate, when you send in the tag and the information."

"What's it for, and what good does it?"

"That's simple. It will give the state's Game Commission accurate information about the movement of stocked fish. That is, whether the stocked fish stay where they are put, whether they go right back downstream for deeper water or whether they go upstream. To have information on these questions will aid the biologists of the Game Commission help the fishermen catch more and larger fish in shorter time of fishing effort."

"How come, and why?"

In the old days there were no dams in Nebraska's streams as we have them today. That means that the catfish in the spring could go upstream to shallow places more suitable for spawning, and where there was more food to raise their young. In late summer and fall they would drift downstream again to deeper water where they would be safe from freezing during the winter months. These fish were wise, and their wisdom was that of the ages. Now, man, for his beneficial use, has put up all these dams and thereby confused the age-old wisdom of the catfish. The confused catfish further confused the fishermen. Some swear they do not move—they do move— they go only down—no, they go only up—they don't spawn anymore—they still spawn.

Every year for some time now, the Game Commission has put at least one skilled man onto the old Missouri river, way up in the north part of the state, about where the Niobrara River joins it. The job of this man, and his crew when he has one, is to trap catfish out of the big Missouri river to transplant them to other Nebraska streams where people have been unable to catch catfish in satisfactory numbers. When these trapped catfish are planted, they are supposed to accomplish two things: first, supply the angler with catches, and secondly, provide breeding fish for that locality. The Game Commission's fish trapper does his trapping in the spring and autumn, because through actual experience it had been found that during the summer months hardly any catfish could be caught. This seems to be sufficient proof to show that actually there is in this old stream a spring and fall migration of catfish.

What happens with the catfish in the other Nebraska streams that have become segmented, nobody knows for sure. That is why your Game Commission goes to all the trouble of tagging many fish and then keeps track of the tag returns that good and civicminded sportsmen and women cooperatively send in. The numbered tags, plus the whereabouts and time when the particular catfish is caught, supply information that eventually will result in better fishing for more people.

In the spring of 1953, 1,000 catfish were tagged. Half of these were stocked into the Middle Loup river near Halsey, and the other half into the North Loup river at Burwell. From the Halsey stocking, nine tags were recovered. All these fish had moved downstream. The shortest distance traveled by a tagged fish was 21 miles, and the longest was 52 miles. Within 4 months from the stocking, the nine fish in the aggregate had traveled 467 miles, or an average per fish of 52 miles.

From the Burwell stocking in the North Loup river, 17 tags were returned to the Game Commission by cooperating fishermen. Of these, one was caught 3 miles from the place of stocking more than 2 months later. Five months after the tagging, one catfish was caught 111 miles from the stocking place, and this one had left the river for it was taken in a canal.

Fish biologists have been attaching small metal tags on the tails of Nebraska's catfish in an effort to learn about the movement of these fish after stocking.

In the aggregate, these 17 tagged fish

had traveled 446 miles, or an average

of 26 miles per fish. None of the tagged

fish were recovered upstream from the

places of stocking. Most were caught

in the neighborhood of dams, presumably because of deep water pools. A

few were caught in tributaries of the

streams stocked. The returns from tagging so far have been small, and therefore

16

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

no far-reaching conclusions can

be formed. There are, however, already some good pieces of information

made available, which, in due time,

may become of much help in formulating management policies to the end

of more fish for less effort by the fishing folks.

no far-reaching conclusions can

be formed. There are, however, already some good pieces of information

made available, which, in due time,

may become of much help in formulating management policies to the end

of more fish for less effort by the fishing folks.

Send serial number, location and time of capture to the Nebraska Game Commission, Statehouse, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Four records have just come in of people catching catfish near Boelus and Dannebrog. These fish were stocked in the spring of 1953 near Halsey in the Middle Loup river and apparently have moved about 120 miles downstream where they are being caught now.

This spring of 1954, 3,000 more catfish were tagged and stocked in six different places. Some interesting information is already coming in, but it is still too scanty to intelligently report.

The personnel of the Game Commission hope that every last one of the fishing people will take note of the tags and promptly, for their own good, send in the tag or its number and tell where and when the fish was caught. The State Game, Forestation and Parks Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, will greatly appreciate the good sportsmanship and kind cooperation.

Maybe you forgot to spit on your bait.

IT'S YOUR HERITAGE

Cont. from page 5

fishing.

So great was the hertitage of free and uncontrolled hunting and fishing that it was a struggle to even introduce and pass a law to make it a felony to dynamite fish. This law, one of our first game laws, was passed at the time the Fish Commission was changed to the Fish and Game Commission

This was the first time that the Commission had personnel with police power to enforce game laws. The first hunting and fishing license was also sold that year.

By 1904, the citizens of Nebraska became aware of the desperate straits of the only remaining big game animals—50 deer and 100 antelope in western Nebraska. Public opinion was finally aroused and both deer and antelope were put on the protected list.

Shortly after World War I, the first pheasant stocking plan was initiated and this was the beginning of Nebraska's most famous game bird. The first season, 3 days long, was in 1927 and 5,000 birds were taken. The following year, during a 10 day season, 35,000 birds were bagged.

The present day Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission was established in 1929. With the addition of the State parks the Commission's scope of responsibility was enlarged to the present day status.

By this time, hunting and fishing was controlled by laws made necessary by the cruel lesson of scarcity.

Soon an even more vicious lesson was forced upon the people of Nebraska along with the rest of the midwest.

During and following World War I, wheat prices were at record highs. Many acres of prairie land, never broken by the plow, were turned to wheat production. This was fabulously profitable during years of average and above average rainfall, but the ensuing drought years proved that cultivation of marginal lands was at the least, a dismal failure and a threat to the national welfare. Economic trouble, in the form of a stock crash, was the prelude to hardship and ruin.

The marginal lands, put into wheat production, were powder dry in the early 1930's and the dust bowl reared its ugly head. This dust bowl covered thousands of square miles of Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and North and South Dakota. It brought a period of darkness over the future of wildlife and fish in all of these areas.

Ponds, streams and lakes dried up and fish died or were killed later in the winter from lack of oxygen or were frozen in the shallow water. Duck populations, with no place to nest, dropped to a point where many believed they would vanish entirely. Pheasants became scarce and quail were killed out entirely by unusually severe winters.

Here was the final lesson that crystallized the pattern for hunting and fishing in Nebraska. Poor land practices and utilizing marginal lands, jeopardize the very existence of wildlife and even men in times of adverse weather conditions; and we had to learn this the hard way. There is some doubt that we have learned this lesson well, if you consider the present dust bowl areas in Colorado and Kansas.

You have had a brief look at some of the highlights of our hunting heritage and seen how important the right to hunt was to the development of Nebraska.

You have seen how nature gave the first warning for us to recognize our responsibilities to this heritage with the disappearance of some of our early wildlife.

The final lesson, the grim drought years, should have taught us the importance of land use in the survival of wildlife and even our own survival.

What the future holds is up to each of us personally, whether we are sportsmen, landowners or professional game managers. Ever increasing hunting and fishing pressure has made the current Nebraska problems, such as farmer-sportsman relations, modern game and fish research and management, the direct and personal concern of each of us.

If we are to maintain our American system of hunting, where the average citizen can participate, we will have to meet our responsibilities.

If we don't, we can look forward to a modification of the old world hunting system, where the hunting rights are for the privileged few, who have fortunes or titles of royalty.

With the great and strong heritage, derived from our forefathers, in mind, we cannot help but face our responsibilities and perpetuate our "free-man" hunting system.

SUMMER ISSUE 17

FOR BETTER FISHING KEEP YOUR REEL CLEAN

Your entire fishing success can depend on one item .... your reel. Keep it clean and use a magnifying glass to check parts for wear. Here's an easy, step-by-step way to do the job.

Toothbrush, pipe cleaners, grease-cutting solvent for cleaning; magnifying glass; regular reel oil; grease for lubricating; a screwdriver and a reel wrench to take reel apart.

Here's how to keep out of trouble later on. Be sure to put all parts in a box, in same order that you take reel apart—and you won't become confused in re-assembling it. Reprint from SPORTS AFIELD Fishing Annual

18 OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

Now comes the next step. You dip the parts in a bowl of the solvent. Let them soak for a while and then scrub them well with an old toothbrush. Photo shows you how.

For small openings, such as bearing race that's shown in the above photograph, use a pipe cleaner for the cleaning job. When finished, set cleaned parts on rag to dry.

Apply a thin coat of light grease to gear surfaces. Wipe excess grease off with a rag. Thin coat of oil will help preserve all metal surfaces of the reel. Try it out.

Keep bearing races lubricated at all times. When fishing, once an hour isn't too often. If you grasp spool, try to move it sidewise, and there is play, have parts replaced.

Trouble spot for wear is pawlsee above — and double thread upon which pawl runs. Check both parts for wear with magnifying glass. When you find wear, order new parts.

Protect reel with a case to keep out dust. Carry oil, grease, tools in plastic box. A vial of oil with an extra pawl, double-thread gear, may save fishing trip from ruin.

This is STRICTLY FOR THE LADIES

Here are a number of answers to the problem of how to prepare fish brought home by fishermen.

YOU have heard an avid fisherman make the statement, "I like to fish but when it comes to eating them, somebody else can do that." In every gathering of fishing enthusiasts, this attitude is bound to show up and you might even hear it in your own home.

The most common method used for preparing fish for the table is to pop them in a skillet and fry them. For many people, fried fish are just about the apex in good eating; for many others, "somebody else" can eat the fried fish.

It is no small wonder that some people dont care for fried fish, when you stop to consider that the major part of our diet consists of fried foods. It is much like the man who says about radishes and cucumbers, "I like them but they don't like me."

These fried foods are fine, if you have the constitution to digest them. Also, with the present public concern on the waistline, fried foods are being watched because of their high calory content.

If you and your family are some of the lucky ones that can eat fried fish and enjoy them, so much the better. Remember that fish are a high protein food that requires just enough cooking to let the flesh pull away from the bones, to bring out its delicate flavor and to leave it moist and tender. If you overcook fish, by any method, it will be tough and dry.

You might be able to entice your family to eat more fish if you would consider some other methods than frying for cooking fish. Broiling, baking and planking are some tasty and easy methods of cooking. A seldom used, but delicious way of preparing fish is boiling or steaming and using the meat water, and roll in some dry cereal such as corn meal, flour, cracker or bread crumbs. One popular method is to dip the pieces of fish in water and roll them in a mixture of V2 cup of flour and V2 cup sifted bread crumbs.

SHALLOW FRYINGFor pan-frying, a heavy cast iron skillet with a Va inch of hot fat is very handy. The fat should be hot but not smoking. Place the fish in the pan, cover and cook at a moderate heat.

DEEP FAT FRYINGFor deep fat frying, most people use a frying basket and enough fat to cover the fish. Heat the fat to 350 degrees. At this temperature, a piece of fresh bread will brown in about 40 seconds. Put only one layer of fish in the basket and cook until an even goldenbrown, which requires about 5 to 7 minutes.

BROILINGIt is very simple to broil fish. You will want the larger size fish, cut into steaks or fillets. Wipe with a damp cloth, salt on both sides and let stand for about 10 minutes to absorb the salt. Grease a shallow pan and put the fish in it with the skin side down. Many cooks use aluminum foil in the shallow pan to make pan cleaning easier. If the fish is oily, you will not after it has cooled. This is known as fish flakes. They may be used in omelets, creamed and served on toast or even used in wonderful tasting salads.

Frying in either shallow or in deep fat has long been a favorite method of preparing fish. Cut the fish in serving portions, either fillets from larger fish or in pieces from smaller fish, about % inch thick. Salt on both sides and let the pieces stand about 10 minutes to absorb the salt. Dip the pieces in liquid, such as beaten egg, milk or have to add grease to the pan.

Slide the broiled fish carefully onto a hot platter, season with pepper, pour on the drippings and serve at once.

BAKINGBaking a whole fish is a flavorable and easy way to prepare the larger size fish.

4-6 pound fish Shortening or fat Stuffing: 1 quart bread crumbs 3 tablespoons chopped onion 1/2 cup celery, finely cut 1 teaspoon thyme or savory seasoning 6 tablespoons melted butter 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon pepperCook the celery and onion for a few minutes in the butter. Mix in the other stuffing ingredients and add to the butter mixture.

Remove the head and tail of the fish, if you prefer. Split the fish down the belly, wipe the fish with a damp cloth, salt it inside and out and let stand about ten minutes.

Preheat the oven to 500 degrees F. Stuff the fish and sew with a string to retain dressing. Place it on a greased rack in a baking pan and sprinkle the top with melted butter. Bake at the high temperature for 10 minutes; then lower the heat to 400 degrees F. and cook 20 to 30 minutes longer.

STEAK OR FILLETS 3 pounds fish steaks or fillets 1/2 cup melted fat or shortening 2 tablespoons lemon juice 1/2 cup finely chopped parsley 1 teaspoon minced onion SaltI suppose you'd rather have them screaming their heads off!

Wipe the fish, remove any bones

and cut into pieces of the size desired

for serving. Salt each piece on both

sides and let stand to absorb salt. To

the melted fat, add lemon juice and

minced onion. Dip each piece of fish

20

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA

into this mixture; place them in a

greased, shallow baking dish and pour

the rest of the fat over them. Bake in

a moderate oven, 350 to 375 degrees F.,

about 25 minutes. If not sufficiently

browned, place under the flame of the

broiling oven.

into this mixture; place them in a

greased, shallow baking dish and pour

the rest of the fat over them. Bake in

a moderate oven, 350 to 375 degrees F.,

about 25 minutes. If not sufficiently

browned, place under the flame of the

broiling oven.

Fillets or pan dressed fish may also be baked with a small amount of fish or meat stock or milk in the bottom of the open baking pan. Chopped onions, celery or green peppers may be added if desired. The seasoning is added to the stock or milk. Bake in a moderate oven, 350 to 375 degrees F., until tender.

PLANKINGFish suitable for either baking or broiling may also be planked. An advantage of this method of cooking is that the fish may be placed on the table without being transferred to a platter. The plank, made from a piece of well seasoned oak, hickory or ash about IV2 inches thick, should be grooved around the edge and have several other grooves cut into the surface to hold the juices from the fish. Your local stores can usually supply suitable planks.

Put the plank into a cold oven and preheat it with the oven. Remove the plank and oil it thoroughly, then place the fish on it and proceed as directed for baking or broiling.

BOILING OR STEAMEDFish, like meats, should be simmered, never boiled. Lean fish are preferred for cooking in water or steam because the flesh, compared with that of fat fish, has less tendency to fall apart. The fish can be protected further from breaking by using a wire basket or a perforated pan or by wrapping in cheesecloth. Simmered fish may be improved in flavor by cooking in any of the following liquids:

Plain salt water—to each quart of water add iy2 tablespoons of salt.

Acid water—to each quart of water add 1/2 tablespoons of salt and 3 tablespoons of lemon juice or vinegar.

Court bouillon—cook 1 cup, each of chopped carrots, onion and celery with 2 tablespoons of fat for 5 minutes; add 6 whole black peppers, 2 cloves, V2 bay leaf, 1 tabelspoon salt, 2 tablespoons vinegar and 2 quarts of water; bring to boil and cook for a few minutes and strain.

BOILING 3 pounds fillets or steaks, or 4 pounds of whole fish 3 tablespoons salt in 2 quarts of simmering waterPlace one layer of fish cut into suitable pieces for serving in a basket or perforated pan. Lower the basket into the simmering, salted water. Cook about 20 minutes or until tender; remove and drain. Serve hot with a rich bright colored sauce.

STEAMED FISHUse the same quantities as for boiled fish. Cut into serving pieces; salt on both sides and let stand for 10 minutes to absorb the salt. Place the fish, one layer deep, in a well oiled steamer and cook about 20 minutes or until tender. Serve hot with a seasoned butter dressing or with tomato sauce.

FLAKED FISHIf more fish is obtained than is needed for a meal of boiled or steamed fish, the unused cooked portion may be flaked and stored in a refrigerator until the following day. These fish flakes may be combined in many ways with other ingredients to give a pleasing variety to menus.

FISH FLAKE OMELET 2 cups of flaked fish 2 tablespoons lemon juice 4 eggs Vi cup milk or fish stock 2 tablespoons minced onion 1 tablespoon minced parsley 1/2 teaspoon of salt pinch of pepper 2 tablespoons fat for cookingAdd the lemon juice to the fish flakes. Separate the eggs, beating the yolks thoroughly and stir in the milk or stock, onion, parsley, salt and pepper. Add the flakes and mix well. Fold the stiffly beaten egg whites into the mixture. Have ready and hot, a smooth, heavy frying pan containing the melted fat. Pour the egg mixture into the pan and let cook slowly over moderate heat until it is cooked through, or about 10 minutes. Then place it in a slow oven (330 degrees F.) until dry on top, about another 10 minutes. When dry enough to the touch, remove the omelet from the pan by folding half over with a spatula and roll it onto a platter. Serve at once

FISH LOAF 2 cups flaked fish 1 tablespoon lemon juice 1/2 cup butter or other fat 1/2 cup flour 1 cup milk 1/2 cup bread crumbs 1/2 cup finely chopped celery 1 tablespoon chopped parsley 1/2 teaspoon saltDrain the fish flakes and add the lemon juice. Melt the butter, stir in the flour and then the milk and cook until the mixture is smooth and thick. Allow to cool and then add the fish flakes, celery, bread crumbs, parsley and salt. Mix until well blended. Mold into a loaf with the hands and place on oiled paper on a rack in an open roasting pan. Bake for about 45 minutes in a moderate oven (350 degrees F.).

FISH SALAD BOWL 21/2 cups of flaked fish 8 slices of bacon, fried and chopped 2 cups of potatoes, boiled and cubed 1/2 cup diced celery 1 cup of chopped cucumbers 1 chopped green pepper 12 radishes, sliced 2 tablespoons of minced onion 1 teaspoon salt pinch of pepper 1/2 cup of ketchup 1/2 cup of mayonnaise crisp lettuce leavesCombine fish flakes, bacon, potatoes, celery, cucumbers, pepper, radishes, onion and seasoning and salad dressing by tossing together with a fork. Add sufficient dressing to moisten; season to taste. Put the mixture into a chilled bowl lined with lettuce leaves.

CREAMED FISH FLAKES 2 cups fish flakes 1/2 teaspoon pepper 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 cup cream 3 teaspoons chopped parsley 2 teaspoons chopped onion 4 teaspoons butter or cooking fatPut butter or fat to heat in a frying pan over a slow fire.

Combine other ingredients with cream in a bowl, adding the fish flakes last. Put into the fat and simmer slowly until thoroughly heated and seasonings are well blended. Serve on toast or with baked potatoes.

TOMATO SAUCE 1 tablespoon shortening 1 small chopped onion 1 tablespoon green pepper 1 tablespoon flour 1/2 cups tomatoes 1/2 teaspoon saltCook onion and green pepper in the fat until tender but not brown. Add the flour, tomatoes and salt. Simmer 10 minutes and strain if desired.

CREAM SAUCE 1/2 tablespoons shortening 1/2 tablespoons flour 1 cup milk 1/2 teaspoon salt pepper to seasonMelt the fat in a double boiler. Blend in the flour, add the milk gradually, stirring until thickened and add seasoning.

SUMMER ISSUE 21

A biologist explains WHAT IS THIS GAME CYCLE?

by George SchildmanWE biologists have made the term "10-year game cycle" a part of our every day language. We use it loosely and vaguely, and as if it were commonly understood. Actually, there is much to be learned about the causes and functions of the cycle. Even students of populations are not in complete agreement yet, on what are and what are not cycles. If we can't agree on the meaning of the term, then you Nebraska hunters certainly must be perplexed when a biologist speaks of cycles.

A dictionary definition of a cycle is: "An interval of time in which is completed one round of events that recur regularly and in the same sequence." Therefore, a cyclic population, be it bird, mammal, fish or insect, is one that repeatedly goes through regular population increases and decreases, for a regular time period. Because animals are living organisms, and therefore are responsive to environmental changes, perhaps we shouldn't stick rigidly to the dictionary definition. Or else we might conclude that there is no such thing as a population cycle.

Sharptail grouse is one of Nebraska's game birds that have regular ups and downs in population numbers, known as cycles.

The "cycles" that we commonly refer to are the fluctuations of numbers of individuals that make up a population. The population is constantly changing—from season to season and year to year. Aldo Leopold* names three types of population curves: The "flat" curve in which the population fluctuates to a small degree, from year to year. The "cyclic" curve wherein the population fluctuates more drastically, and at regular intervals. These intervals are sufficiently regular to predict the approximate time of peak and low populations. The peaks and lows are characteristically near the same level. The third type is termed "fluctuating." This one exhibits severe changes of population without regular intervals.

Animal cycles, as we think of them, indicate changes in numbers from low to high to low again, and occuring with periodic repetition. Not all cycles are of the same length. Some species of mice and foxes show a 4-year cycle, while partridge in Europe have a 7-year cycle and rabbits, grouse, and lynx are representatives of 10-year cycles. These are average lengths.

For example, the 10-year cycle may vary from 8 to 12 years. Cycles are the result of some influence that affects a species over a large expanse, such as its continental range. However, for any one year, local and seasonal fluctuations may be out of line with the general cyclic trend. There are other exceptions to this cyclic pattern that are not just local in nature. European hares and Hungarian partridges are reported to have 8-year cycles, but they are of 10-year length in Canada. The cycles on the two continents are not consistent cycle-wise, for two similar species.

Canadian workers report that peaks are not synchronized all over the continent, but begin in the north with a year or so lag behind peak populations in southern Canada. This is the case at least for some of the cycles. Another feature of cycles, is that the degree of fluctuation is greatest nearer the periphery of the range where environmental conditions are more adverse. However this isn't the only explanation, as shown by ruffed grouse populations nearer the center of its range.

Cycles appear to be largely a phenomenon of the north. More species are cyclic and the cycles are more pronounced in Canada and Northern Europe. Cycles are virtually absent in the southern United States.

Synchronization, or something very near to it, is another curious feature of this population phenomenon. It is generally considered that years ending in 1 or 2 (1941, 1942, etc.) are the years of peak populations of the northern game cycle. These peaks are followed by a decline which produces a low point for the years ending in 6 or 7. The build-up to a peak and the decline to a low appear to be synchronized even though a species range is disconnected.

Grouse populations on islands isolated from the mainland start their declines at the same time as those on the mainland. Roughed grouse populations in Wisconsin, cottontails in the lake states, and muskrats in Iowa appear to have somewhere near synchronized cycles.

Very recently, Dr. Paul L. Errington, working on Iowa muskrats, recognized evidence of some other characteristics of cyclic phenomenon. These were physiological and psychological in nature. During the peak years muskrats showed greater resistance to "muskrat disease" and some of them even recovered from it. At about the time grouse and hares started their decline hundreds of miles to the north, the muskrats apparently lost their resistance.

During the latter part of the upswing of the cycle some animals born

early in the year produced young

themselves the same year. This last

feature of the cycle was also noted

among Nebraska 'rats. Errington also

noted that during the upgrade and

22

OUTDOOR NEBRASKA